Summary

Sexually transmitted rectal infections with Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) have been well documented in men who have sex with men (MSM). Few studies have described infections in women who engage in anal intercourse. We performed testing for rectal infections in women who reported ano-receptive intercourse at the Miami Dade Health Department Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) clinic and report the prevalence and characteristics of women with rectal CT or GC infections. Our results revealed a prevalence of 17.5% for rectal chlamydia and 13.4% for rectal gonorrhoea. Urine-based screening alone would have missed 6% of rectal chlamydia infections and 35% of rectal gonorrhoea infections. Anal symptoms were reported in 12.5% of women with rectal chlamydia infections. The only associated factor identified was an age less than 28 years. We conclude that rectal screening for CT and GC should be included in STD prevention strategies, especially in the younger population.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, women, sexually transmitted infections, rectal infections, screening

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to increase in the USA, and women are at an increased risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV and other STIs. Current national statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show increasing number of infections with Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) among women and also high rates of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) among men and women. The national transmission rate of CT increased from 539.8 to 583.8 per 100,000 women between 2007 and 2008.1 The CDC data inform about infections in the genitourinary tract. However, recent studies suggest that infections occurring in sites other than the genitourinary tract, such as the pharynx and rectum, are under-diagnosed and likely account for continuing transmission.2 Oropharyngeal and rectal infections caused by CT and GC have been previously described in men who have sex with men (MSM).3

Few data exist regarding the prevalence of rectal infection with CT or GC in women who practice receptive anal intercourse with few prevalence studies but no national surveillance data. Miami is a multiethnic city with high prevalence of both HIV and STIs. In 2008, the rate of CT infections in Miami-Dade county was 316.9 per 100,000 population, and the national rate was 401.3 per 100,000 population.4 Preliminary data obtained in the Miami Dade Health Department (MDHD) Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) clinic suggests that anal intercourse is a common practice among women of ethnic minorities, especially of Hispanic origin.5 Diagnosis and treatment of rectal CT and GC infection in women who engage in receptive anal intercourse is not part of routine recommended STI screening, and there is no approved available testing. Routine STI screening with urine nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) can detect urethral infections but may miss rectal infections.3,6

The objectives of this study were to determine the prevalence of rectal chlamydia and gonorrhoea in women that practice anal intercourse and to describe the demographic characteristics and risk factors of women diagnosed with these infections in the MDHD STD clinic.

Methods

In May 2007, at the MDHD STD clinic, we included routine screening for rectal CT and GC in individuals who practice receptive anal intercourse. Rectal screening was done in combination with standard STI testing in all women (HIV and syphilis screening, urine or cervical NAAT for CT and GC). Validation studies were performed by the Florida Department of Health (DOH) laboratory services prior to utilization of the test. The APTIMA Combo 2 Assay® (Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for rectal, urine and cervical specimens. The sensitivity of the urine APTIMA Combo 2 Assay® for cervical infections reported by Gen-Probe for GC and CT in women is 91% and 95%, respectively.7 However, there are no data that correlate with rectal infections.

The study consisted of a retrospective review of medical records of all women tested for rectal CT and GC from May 2007 to August 2008. Information was abstracted from the DOH STD clinic medical charts and recorded into an Excel database with protected patient identifiers. Approvals from the University of Miami and the DOH Institutional Review Boards were obtained prior to any study-related interventions.

All the women were asked the routine screening questions from the standard DOH STD form. The questions specifically enquired about rectal symptoms in those who reported receptive anal intercourse. Rectal swabs were collected by inserting the swab 1–2 cm into the anal canal from all women reporting anal intercourse irrespective of the presence or absence of symptoms. Rectal symptoms were described as pain, discharge, bleeding, ulceration, constipation, diarrhoea or tenesmus.

The data collected included: age, race, ethnicity, income, number of partners within the last two months and one year, history of STIs, symptoms, abnormal physical examination findings, urine testing for CT and GC, co-infection with HIV and other STIs. Age was categorized as either above or below the median. Race was defined as black, white or other. Ethnicity was defined as Hispanic, non-Hispanic or other. Income was categorized as either above or below the Florida poverty line for a family of two. Abnormal physical exam findings were recorded as the presence or absence of findings. Urine APTIMA test results for CT and GC were recorded as positive or negative. Known HIV status prior to testing was documented as the presence or absence of co-infection. A history of STIs was classified as either the presence or absence of one or more STIs (CT, GC, syphilis or genital herpes) in the past. Infectious syphilis was defined as the presence of primary, secondary or early latent syphilis.

The abstracted descriptive data were coded and uploaded into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software for statistical analysis. Pearson Chi-Square testing was used to determine factors associated with CT/GC rectal infection. A P value of less than 0.05 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was considered to be significant.

Results

A total of 3398 women received routine STI screening during the study period. Ninety-seven of these women received rectal GC and CT testing in addition to routine STI testing. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the women tested and their test results. Most of the women tested were from minority ethnic/racial groups, Hispanics or black. The median age of the women tested was 28 years. The majority of women tested reported an income below the poverty line, reported no symptoms and had a normal physical examination. The symptoms reported by two women included rectal pain, rectal bleeding and constipation; one of the symptomatic women had a herpetic ulceration at the time of diagnosis which likely explained her pain. Seventeen women had positive rectal swabs for CT; 16 of them had positive urine CT tests. Thirteen women had positive rectal swabs for GC; eight of them had positive urine GC tests. There were three women with rectal CT/GC co-infections.

Table 1. Results and baseline characteristics of women who received rectal GC and CT testing.

| Total of women screened (n) = 97 | |

|---|---|

| Total of women positive rectal infections | 27 (27.8%) |

| Rectal infections with CT | 17 (17.5%) |

| Rectal infections with GC | 13 (13.4%) |

| Rectal infections with CT and GC | 3 (3%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanics | 62 (63.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 35 (36.1%) |

| Age in years (median [range]) | 28 (17–46) |

| Less than 28 | 52 (53.6%) |

| More than 28 | 45 (46.4%) |

| Income (per year) | |

| Less than US$14,000 | 81 (87.1%) |

| More than US$14,000 | 12 (12.9%) |

| Number of partners | |

| 2 or more in the previous 2 months | 14 (14.4%) |

| 4 or more in the previous 12 months | 11 (11.3%) |

| Anal symptoms | 2 (2%) |

| Abnormal anal exam | 5 (5.2%) |

| Urine testing | |

| CT | 16 (16.5%) |

| GC | 8 (8.2%) |

| History of other STIs | 51 (52.6%) |

| HIV-1 positive | 2 (2.1%) |

| Infectious syphilis | 7 (7.2%) |

CT = Chlamydia trachomatis; GC = Neisseria gonorrhoeae; STI = sexually transmitted infection

Table 2 shows the factors associated with rectal CT infection. Univariate analysis was performed. Twenty-two percent of women were younger than 20 years. An age less than 28 was associated with rectal CT infection with a significant P value. Twenty-four (26%) of the tested women had positive urine tests for either CT or GC, and 30 (32%) had a positive rectal infection with either CT or GC.

Table 2. Factors associated with rectal CT infection in women who practice ano-receptive intercourse (n = 97).

| Women without rectal CT infection | Women with rectal CT infection | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Less than 28 years | 38 (47.5%) | 14 (82.3%) | 0.009 |

| More than 28 years | 42 (52.5%) | 3 (17.7%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 53 (66.25%) | 8 (47%) | 0.146 |

| Non-Hispanic | 27 (33.75%) | 9 (53%) | |

| Income per year (n = 93) | |||

| Less than US$14,000 | 69 (87.3%) | 12 (85.7%) | 0.867 |

| More than US$14,000 | 10 (12.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | |

| Number of partners | |||

| 2 or more in previous 2 months | 13 (16.6%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0.256 |

| 4 or more in previous 12 months | 10 (12.8%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0.418 |

| Symptomatic (n = 95) | 2 (2.5%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0.07 |

| Abnormal physical exam | 3 (5.2%) | 2 (12.5%) | 0.257 |

| History of STI (n = 93) | 43 (54.4%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0.851 |

| HIV-1 positive | 2 (2.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.233 |

CT = Chlamydia trachomatis; GC = Neisseria gonorrhoeae; STI = sexually transmitted infection

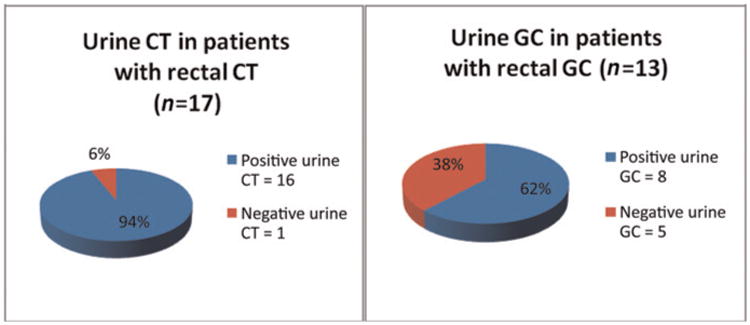

Figure 1 shows the correlation between urine and rectal testing positivity. Most women who tested positive for rectal CT had a positive urine test. However, one-third of women with rectal GC did not have urethral infection.

Figure 1.

Correlation between rectal and urine CT and GC testing. CT= Chlamydia trachomatis; GC= Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Discussion

We found very high rates of rectal infections with CT and GC in our clinic. Twenty-seven percent of the women tested were positive for rectal infections: 17% with rectal CT and 13% with rectal GC.

Different rates have previously been described in different populations and most of the available data are in MSM. Prevalence in this population is as high as 8.5% in some reports.8,9 Data regarding rectal infections in women are limited and a recent study performed by Sethupathi et al. 10 suggested that rates in women may also be high; 12.5% of high-risk women at their genitourinary clinic in the UK tested positive for rectal CT. Our results concur with theirs to reveal higher rates of infections in women than in MSM.

In our sample, younger age was strongly associated with rectal infection with chlamydia. This finding was also reported by Sethupathi et al.,10 who found that 22% of women with rectal CT were less than 20 years of age. This could be due to the higher susceptibility of younger women to infection or to higher prevalence of infected partners at younger ages.

Data regarding correlation with infections from genital and extragenital sources are also limited and mainly described in MSM. In the MSM population, infections in the rectum and in the pharynx would be missed relying solely on urine or urethral testing.6 There have been reported studies emphasizing the need for extragenital site testing. A study conducted in a men's clinic in Toronto showed that 60.2% CT and 84.3% of GC pharyngeal infections would have been missed relying solely on urine or urethral testing.3 Kent et al.6 collected data from two clinic settings to achieve a large sample of MSM documenting the prevalence of extragenital and urethral infections with CT and GC: 54% of rectal CT infections and 21% of rectal GC infections would have been missed if urine testing alone was performed for STI screening. We also found discordant results with urine and rectal samples in our group of women. Our data showed that 6% of CT and 38% of GC rectal infections would have been missed if urine testing alone was performed. Bachmann et al. compared culture and NAAT for the diagnosis of rectal GC and CT. Their results showed a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 95.5% for rectal GC.11 The higher sensitivity of rectal NAAT is a possible explanation for the higher discordances among the urine and rectal GC results. Although the discrepancy between urine or urethral and extra-genital sites is higher in MSM, our study reiterates the need for extragenital screening for STIs in high-risk populations of both men and women since undiagnosed rectal infections may account for increased transmission of STI and HIV in high-risk settings.

Similar to urogenital infections, most individuals with rectal infections are asymptomatic. In current reports in the USA, 52–86% of MSM with rectal infections were asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.6,9 Only 2% of the tested women in our sample reported anal symptoms and there was no association between symptoms and rectal infections. Our results regarding asymptomatic infections were similar to those reported by Annan and to a study performed in a San Francisco STD clinic analysing rectal infections among women who received pelvic examinations.2 The high reported rates of asymptomatic rectal infections show the importance of including rectal STI testing during screening for all who report anal intercourse, even in the absence of symptoms.

Most of the women tested in our sample were Hispanic or African American, and we found high rates of infections in both groups. This is not surprising since we previously reported that 35% of Hispanic and 10% of African American women attending our clinic engage in anal intercourse.5

Although we identified a high prevalence of rectal CT infections in the women tested, co-infection with syphilis and HIV was not common; there were no cases of HIV co-infection. This differs from data reported in MSM. Annan et al. 9 reported CT infections in a large cohort of London, UK, MSM with an HIV co-infection rate of 31.2%. Our clinic also reported high rates of co-infection in MSM.12

There have been reports from early prevalence studies isolating CT from the rectal mucosa of women not engaging in receptive anal intercourse. These infections were attributed to autoinoculation with cervico-vaginal contents.13,14 Barry and colleagues also reported no correlation between rectal infections and anal intercourse. They also considered non-sexual inoculation of the rectum from vaginal secretions.2 Our data does not fully support this concept because of discordant rates between the rectal and urethral infections. However, those women in our study with rectal infections alone may have acquired the infection through autoinoculation from a spontaneously cleared urethral or vaginal infection. A study performed by Geisler et al.15 to describe the natural progression of urogenital CT infections reported spontaneous resolution of CT in 18% of infected women prior to treatment. Other possibilities include falsely positive or negative test results, and all of these factors were considered by Barry et al.2 in their STD clinic cohort study.

Additional studies are needed to determine if treatment outcomes differ among rectal and cervico-urethral infections that may account for discordant test results. Steedman and McMillan16 reported data suggesting that the standard dosing of azithromycin for the treatment of asymptomatic rectal CT infections may be less effective. Treatment may differ depending on the site of infection. If rectal infections are not adequately treated with the conventional standards for urogenital infections, the rectum can remain a reservoir for STIs and increase the risk of such infections as well as HIV transmission.

Currently, there are no approved validated NAATs for the detection of rectal CT and GC infections, and validation by local laboratories is required for diagnosis. Validation studies were performed at the MDHD STD clinic for the use of the present NAAT. Although the diagnostic standard is culture, NAAT is more sensitive and highly favoured for genital infections.17 Bachmann and colleagues conducted a study to compare culture and NAAT performances for rectal CT and GC diagnoses. They found NAAT significantly more sensitive in comparison to cultures with sensitivities of 66.7–71.9% for cultures and 100% for NAAT.11 These newer amplification testing modalities are superior to the standard cultures and should be evaluated by the authorizing authorities for approval for extragenital site infections.

There were several limitations to our study. Data were collected retrospectively by reviewing chart documentations. At times, charts were not fully completed which resulted in missing data. Chart documentation also may not have captured our intended, entire target population as some women may not have reported anal sex. Our sample size was also very small which limits the power of our study. Since rectal testing is not routine, not all clinic providers performed rectal testing and some women who were offered it, refused. Rectal screening was only offered to women who admitted to ano-receptive intercourse, and the rates of rectal infections may have been higher if we included all women for testing.

In conclusion, the rates of rectal infections identified in our population of women engaging in anal intercourse were very high, and most were asymptomatic infections. Routine rectal screening in women with approved tests is a necessity as part of STI and HIV prevention strategies. Further prevalence studies need to be performed to compare rectal infection rates in men and women, in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, and in those who do and do not engage in ano-receptive intercourse. These results may become useful to inform future guidelines for STI screening.

References

- 1.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance. See http://cdc.gov/std/stats08/chlamydia-figs.htm (last checked 5 June 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry PM, Kent CK, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Results of a program to test women for rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:753–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d444f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ota KV, Fisman DN, Tamari IE, et al. Incidence and treatment outcomes of phrayngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection in men who have sex with men: a 13-year retrospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1237–43. doi: 10.1086/597586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance, 2008. CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcaide ML, Castro J, Pereyra M, Hooton TM. Sexually transmitted diseases among women of different races and ethnicities in the Miami Dade Health Department Sexually Transmitted Diseases Clinic. IDSA/ICAAC Meeting Poster; Washington DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W, et al. Prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:67–74. doi: 10.1086/430704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gen-Probe. Gen-Probe Incorporated; Gen-Probe. APTIMA® for GC and CT. See http://www.gen-probe.com/products/aptima.aspx (last checked 18 August 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivens D, MacDonald K, Bansi L, Nori A. Screening for rectal clamydia infection in a genitourinary medicine clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:404–6. doi: 10.1258/095646207781024793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annan NT, Sullivan A, Nori A, et al. Rectal chlamydia – a reservoir of undiagnosed infection in MSM. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:176–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethupathi M, Blackwell A, Davies H. Rectal Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women. Is it overlooked? Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21:93–6. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, et al. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatic rectal infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1827–1832. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02398-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alcaide ML, Moneda A, Von K, Dean K, Vasquez M, Castro J. International Society for STD Research meeting poster. London: 2009. Rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea infections in men that have sex with men. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pratt BC, Tait IA, Anyaegbunam WI. Rectal carriage of Chlamydia trachomatis in women. J Clin Pathol. 1989;42:1309–12. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.12.1309-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RB, Rabinovitch RA, Katz BP, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis in the pharynx and rectum of heterosexual patients at risk for genital infection. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:757–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-6-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geisler WM, Wang C, Morrison SG, et al. The natural history of untreated Chlamydia trachomatis infection in the interval between screening and returning for treatment. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:119–23. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318151497d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steedman NM, McMillan A. Treatment of asymptomatic rectal Chlamydia trachomatis: is single-dose azithromycin effective. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:16–8. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC. Clinic-based testing for rectal and pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections by community-based organizations – five cities, United States, 2007. Morb Mort Week Rep 26. 2009 Jul 10;58:716–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]