Abstract

Objective

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is prevalent and associated with clinically significant consequences. Developing time-efficient and cost-effective interventions for NSSI has proven difficult given that the critical components for NSSI treatment remain largely unknown. The aim of this study was to examine the specific effects of mindful emotion awareness training and cognitive reappraisal, two transdiagnostic treatment strategies that purportedly address the functional processes thought to maintain self-injurious behavior, on NSSI urges and acts.

Method

Using a counterbalanced, combined series (multiple baseline and data-driven phase change) aggregated single-case experimental design, the unique and combined impact of these two four-week interventions was evaluated among ten diagnostically heterogeneous self-injuring adults. Ecological momentary assessment was used to provide daily ratings of NSSI urges and acts during all study phases.

Results

Eight of 10 participants demonstrated clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI; six participants responded to one intervention alone, whereas two participants responded after the addition of the alternative intervention. Group analyses indicated statistically significant overall effects of study phase on NSSI, with fewer NSSI urges and acts occurring after the interventions were introduced. The interventions were also associated with moderate to large reductions in self-reported levels of anxiety and depression, and large improvements in mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal skills.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that brief mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal interventions can lead to reductions in NSSI urges and acts. Transdiagnostic, emotion-focused therapeutic strategies delivered in time-limited formats may serve as practical yet powerful treatment approaches, especially for lower-risk self-injuring individuals.

Keywords: Nonsuicidal Self-Injury, Single-Case Experimental Design, Treatment Components, Transdiagnostic, Ecological Momentary Assessment

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI; i.e., the deliberate destruction of one’s own bodily tissue without suicidal intent and for reasons not socially sanctioned) is prevalent, with a recent meta-analysis showing pooled lifetime prevalence estimates that range from 5.5 to 17.2% (Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking, & St. John, 2014). NSSI occurs across the range of psychiatric disorders (e.g., Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006; Selby, Bender, Gordon, Nock, & Joiner, 2012) and is associated with clinically serious consequences, including physical injury, medical complications, heightened negative emotions, and lower functioning (e.g., Briere & Gil, 1998; Nock et al., 2006; Turner, Austin, & Chapman, 2014). Converging findings also show that NSSI is a strong prospective predictor of suicidal behavior (e.g., Bryan, Rudd, Wertenberger, Young-McCaughon, & Peterson, 2015; Wilkinson, Kevin, Roberts, Dubicka, & Goodyer, 2011).

The Four-Function Model (Nock, 2009; Nock & Prinstein, 2004) has garnered the strongest empirical support of existing NSSI theories. Of the four proposed reinforcement processes, automatic negative reinforcement (ANR; NSSI to reduce or escape from aversive thoughts or emotions) is the most commonly endorsed; for example, in one study, 65% of self-injuring individuals endorsed ANR compared to only 4% to 25% for the other functions (Nock, Prinstein, & Sterba, 2009). The prominent role of decreased aversive cognitions or feeling states in maintaining self-injury is also central in other NSSI theories (e.g., Chapman, Gratz, & Brown, 2006; Klonsky, 2007), and supported by self-report, ecological momentary assessment (EMA), and laboratory studies (e.g., Allen & Hooley, 2014; Franklin et al., 2010; Nock et al., 2009).

Unfortunately, few interventions for NSSI have consistently demonstrated efficacy (e.g., Franklin et al., 2016; Glenn, Franklin, & Nock, 2015). Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993) has accrued an impressive body of evidence to support its efficacy for treating borderline personality disorder (BPD; e.g., Kliem, Kroger, & Kosfelder, 2010); however, it is not clear that it outperforms active control conditions in the treatment of NSSI (e.g., Linehan et al., 2006; McMain et al., 2009). DBT also may lack practicality for many patients and settings (e.g., Pasieczny & Connor, 2011) and be more intensive than necessary for some self-injuring individuals (e.g., Andover, Schatten, Morris, & Miller, 2014). Findings from studies of emotion regulation group therapy (ERGT; Gratz & Gunderson, 2006), which includes a multitude of emotion regulation and acceptance-based skills, are encouraging for NSSI (e.g., Gratz & Tull, 2011; Gratz, Tull, & Levy, 2014); however, ERGT has primarily been tested in female samples with at least subthreshold BPD who also received concurrent individual therapy. In sum, developing evidence-based, stand-alone interventions for NSSI as it presents in diagnostically diverse samples and outside the context of a BPD diagnosis remains a high priority.

Existing cognitive-behavioral treatments for NSSI also contain many components, making it difficult to define the specific ingredients responsible for improvements when they occur (e.g., Lynch & Cozza, 2009; Turner et al., 2014). Advancing our knowledge about key therapeutic strategies for NSSI has the potential to improve not only the efficacy, but also the efficiency and feasibility, of extant treatments. Promoting specific, adaptive, and nonavoidant strategies for responding to intense emotion may directly address the functional processes that have been shown to typically maintain NSSI, and thus be critical for effective treatment.

Mindfulness, defined as observing and attending to one’s present experiences with acceptance and a nonjudgmental attitude (Bishop et al, 2004), is one strategy that holds promise for treating NSSI, particularly when the emphasis is on becoming more mindful of internal experiences. Self-injuring individuals evidence deficits in self-reported emotion awareness (e.g., Dixon-Gordon, Tull, & Gratz, 2014; Klonsky & Muehlenkamp, 2007; Wupperman, Fickling, Klemanski, Berking, & Whitman, 2013) and high self-reported experiential avoidance (e.g., Howe-Martin, Murrell, & Guarnaccia, 2012; Najmi, Wegner, & Nock, 2007). Individuals with a history of NSSI but none in the past year also report greater acceptance of emotions than those currently engaging in NSSI (Anderson & Crowther, 2012). Further, mindfulness has been shown to partially mediate the relationship between depression and NSSI, highlighting its protective role (Heath, Carsley, De Riggi, Mills, & Mettler, 2016). When NSSI serves the avoidant function of relieving affect perceived as intolerable, fostering mindful awareness of emotion may reduce reliance on this behavior. Although increasing emotion awareness and acceptance is a key target in ERGT and mindfulness is considered a core skill in DBT, knowledge regarding the unique effects of mindful awareness (in isolation from other strategies) on NSSI is lacking.

Another emotion-focused strategy that may directly address the functional mechanisms that maintain NSSI is cognitive reappraisal, which involves thinking about emotion-eliciting stimuli in a way that diminishes the emotional impact (Campbell-Sills, Ellard, Barlow, 2012). Negative associations between self-reported levels of reappraisal and NSSI have been observed in cross-sectional (e.g., Voon, Hasking, & Martin, 2014a) and longitudinal research (e.g., Tatnell et al., 2013). Self-injuring individuals also tend to demonstrate dysfunctional appraisal processes (e.g., Andover & Morris, 2014; Franklin et al., 2010). Findings from prospective studies have also shown that individuals currently engaging in NSSI are less likely to use reappraisal than those who stop this behavior (Andrews, Martin, Hasking, & Page, 2013), and that reappraisal at baseline protects against worsening NSSI medical severity over time when controlling for other emotion regulation strategies (Voon, Hasking, & Martin, 2014b). Using reappraisal to change the experience of emotion may help prevent negative affect from escalating to a level at which urges to engage in NSSI arise. Similar to mindfulness, however, although several existing treatments that have been tested for self-injury include cognitive elements (e.g., Andover et al., 2014), the unique and specific effects of reappraisal on NSSI are not well-understood.

Research that distills the specific effects of mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal on NSSI would shed light on the degree to which these are potent and critical treatment components. Given research to suggest that heightened emotion awareness facilitates the use of reappraisal (e.g., Garland, Hanley, Farb, & Froeliger, 2015; Gross & Jazaieri, 2014), learning to think more flexibly about emotion-provoking situations may be less useful without training in mindful emotion awareness. Conversely, promoting mindful emotion awareness without teaching reappraisal may leave self-injuring individuals devoid of adaptive strategies for changing the intensity of affect when needed. Thus, it would be informative to determine not only whether each strategy is effective in isolation, but also whether adding the alternative intervention results in additive benefit for those who do not respond to one strategy alone.

In this study, we sought to directly test the effects of two emotion-focused interventions (mindful emotion awareness training and cognitive reappraisal/flexibility) on NSSI using a counterbalanced and combined series (multiple baseline and data-driven phase change) aggregated single-case experimental design (SCED) (Barlow, Nock, & Hersen, 2009). Participants completed daily assessments of NSSI throughout baseline, intervention, and four-week follow-up phases. Primary aims were to evaluate (1) whether each intervention, when administered alone, produces clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI, (2) whether adding the alternative intervention enhances reductions in NSSI for individuals who do not respond to the initial intervention, and (3) whether gains are maintained during follow-up. It was hypothesized that (1) the initial intervention would result in clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI, (2) adding the alternative intervention would enhance reductions in NSSI for those who do not respond to the initial intervention alone, and (3) gains would be maintained during follow-up.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 10 self-injuring individuals. Inclusion criteria were: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) meet criteria for NSSI disorder (a condition for further study included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. [DSM-5]; American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which includes ≥ five days of NSSI in the past year, (3) engagement in NSSI for ANR, and (4) stability on psychotropic medications. Exclusion criteria were: (1) current symptoms warranting an immediate higher level of care, including suicidal intent, severe mania, florid delusions or hallucinations, or current or recent (within 3 months) substance use disorder (not including caffeine, nicotine, or cannabis use disorder), or (2) concurrent psychotherapy for NSSI or related problems. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. On average, participants reported 3.6 acts of NSSI over the past month at the intake (SD = 4.1; range 1 to 15).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Age | Sex | Race | Ethnicity | Education | Principal Diagnosis | Additional Diagnoses | NSSI Method | Psychotropic Medication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 21 | F | W/C | NH | Some College | PDD (GAD) | SOC | Cutting | Antidepressant |

| P2 | 19 | F | Other | H | Some College | None | None | Cutting | None |

| P3 | 30 | F | W/C | NH | Bachelor’s | BPD | SOC, OSDD | Cutting, Severe Picking | None |

| P4 | 19 | F | MR | NH | Some College | OCD & OSAD | SOC, SP (BII), SP (Other) | Severe Scratching | Stimulant |

| P5 | 18 | F | A | NH | Some College | PDD w/persistent MDD | SOC | Severe Scratching | None |

| P6 | 21 | F | A | NH | Some College | PTSD | BPD, SOC, GAD, PD, OCD | Cutting | Mood stabilizer, Benzodiazepine |

| P7 | 25 | M | W/C | NH | Bachelor’s | MDD | None | Severe Picking | Antidepressant |

| P8 | 22 | F | W/C | NH | Some College | MDD & GAD | SOC, PTSD, PD, AG, OCD, ADHD, UNDD | Cutting | None |

| P9 | 19 | F | W/C | NH | Some College | SOC | GAD | Hitting, Severe Scratching | None |

| P10 | 19 | F | W/C | NH | Some College | SOC | OSAD, SP (Driving) | Hitting | None |

Note. Only clinical diagnoses presented. M = male; F = female; W/C = White/Caucasian; A = Asian; MR = Multiracial; H = Hispanic; NH = non-Hispanic; ADHD = attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder; AG = agoraphobia; BPD = borderline personality disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; OSAD = other specified anxiety disorder; OSDD = other specified depressive disorder; PD = panic disorder; PDD = persistent depressive disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; SOC = social anxiety disorder; SP = specific phobia; BII = blood-injection-injury type; UNDD = unspecified neurodevelopmental disorder.

Study Design

To evaluate the unique and combined impact of the two interventions, a counterbalanced, combined-series (multiple baseline and data-driven phase change) design was used (Barlow, Nock, & Hersen, 2009). Participants were randomly assigned to a two- or four-week baseline phase and the initial four-week intervention. Thus, the randomization conditions were: two-week baseline + mindful emotion awareness, four-week baseline + mindful emotion awareness, two-week baseline + cognitive reappraisal, and four-week baseline + cognitive reappraisal. The initial baseline served as a control condition to establish levels of NSSI in the absence of treatment, and to potentially demonstrate that changes in NSSI occurred when and only when the intervention was applied. Following the first four-week intervention, phase change was determined based on idiosyncratic changes in NSSI. Participants who responded to the initial intervention (defined as ≥ 50% reduction in average number of NSSI urges and acts per week from the baseline phase) entered a four-week follow-up phase. Participants who did not respond to the initial intervention (defined as a ≤ 25% reduction in average number of NSSI urges or acts per week from baseline) received the alternative intervention before entering the follow-up phase.1 This data-driven phase change strategy allowed for potentially strong inferences about effects as a function of each intervention and the combination of both interventions, and was clinically desirable by flexibly determining when to apply and withdraw treatment on a case-by-case basis.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board and the study was pre-registered with ClinicalTrials.gov. Participants were referred by Boston-area institutions conducting research or treatment with self-injuring individuals; online research listings were also used for recruitment. Interested individuals completed a brief phone screen to determine eligibility. Those who appeared eligible presented for an in-person screening, during which the lead investigator obtained informed consent, conducted clinician-rated interviews, and administered self-report assessments. Participants completed all self-report assessments on their smartphones using SymTrend, technology developed for real-time data collection. Participants received daily and weekly text message reminders via SymTrend to complete the assessments. At the end of the study, participants received monetary compensation up to $300 based on number of phases completed plus a bonus for ≥ 80% compliance with assessments. Participants were contacted during the spring of 2016 for a phone interview to assess NSSI since the study.

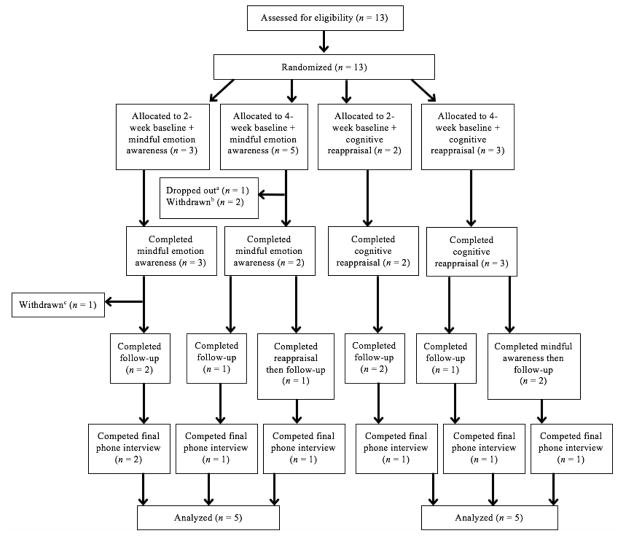

Participant flow is presented in Figure 1. The majority of individuals who were screened out at the phone screen were determined to not meet the NSSI frequency inclusion criterion. All 13 individuals who completed the screening visit were eligible and randomized. Of these, one was withdrawn before entering treatment due to no NSSI urges or acts occurring during the baseline phase. One dropped out after the first treatment session, citing the time commitment. One was withdrawn after Session 3 due to clinical deterioration and self-reported reluctance to be forthcoming with information due to the audio recorder, which was used during each session for purposes of monitoring adherence to the protocol. One participant (P8) was withdrawn after the third session of the second intervention to coordinate an inpatient hospitalization due to the development of imminent suicidal potential. Given that P8 received one intervention prior to their withdrawal, this individual is included in the results presented below.

Figure 1.

Participant flow. a One participant dropped out during the initial intervention. b One participant was withdrawn during the baseline phase and one participant was withdrawn during the initial intervention. c P8 was withdrawn during the second intervention.

Interventions

The mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal and flexibility modules of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP; Barlow et al., 2011) were used for intervention content. The UP is a cognitive-behavioral treatment designed to address underlying temperamental processes across the emotional disorders and is comprised of six core therapeutic skills, including mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal. The UP was selected for use in this study for three reasons: 1) its primary focus on ameliorating aversive reactions to intense emotion, which directly addresses the functional mechanisms that often maintain NSSI, 2) its transdiagnostic nature, and 3) its modular format, which permits extraction of individual treatment components. Although its treatment strategies are not necessarily “new,” the UP differs from traditional single-diagnosis cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) protocols in that each core skill targets the mechanistic processes responsible for symptom maintenance across the full range of emotional disorders (e.g., aversive and avoidant reactions to intense emotion). The UP also differs from DBT in its focus on a relatively small number of therapeutic skills, each of which seeks to directly engage the treatment’s putative mechanism of action: extinction of distress in response to intense emotion. Study interventions closely followed the published UP manual (Barlow et al., 2011) with three modifications: 1) each module was delivered over four (instead of 2 to 3) 50- to 60-minute sessions, 2) examples of skill applicability to NSSI were presented in session and added to the client workbook chapters, and 3) references to other UP concepts were removed from each workbook chapter.

Session 1 of mindful emotion awareness training included an introduction to the concept of nonjudgmental, present-focused awareness of emotions, and a formal mindfulness exercise was practiced in-session. Session 2 consisted of practicing mindful emotion awareness during an emotion-producing song, and Sessions 3–4 consisted of practice with a brief and portable emotion awareness exercise for use in daily-life emotional situations. Session 1 of cognitive reappraisal included an introduction to the concept of automatic appraisal, a discussion of the reciprocal relationship between thoughts and emotions, and identification of core automatic appraisals using a downward arrow exercise. Session 2 focused on two common thinking traps (probability overestimation and catastrophizing), and Sessions 3–4 focused on generating more flexible, alternative appraisals. Homework corresponding to each session was assigned weekly. During intervention phases, participants also received a daily text message reminder through SymTrend to practice the relevant skill. The aim of this ecological momentary intervention (EMI; Heron & Smyth, 2010) component was to facilitate skill acquisition.

The therapist was a masters level doctoral student with three years of experience who had received formal training and certification in the UP. Adherence was monitored during weekly supervision meetings. A randomly selected 20% of session audio recordings were rated for adherence and competency by the lead developer of the UP treatment. Adherence ratings, which included an item that assessed whether any disallowed interventions were delivered, were all 100% and the mean overall session rating was 4.8 on a scale of 0 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

Measures

Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI; Nock et al., 2007)

The SITBI was administered to confirm eligibility at the screening visit. This is a structured interview that assesses the presence, frequency, and characteristics of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in the past week, past year, and over one’s lifetime. The SITBI has shown good interrater reliability and test-retest reliability over a six-month interval, as well as strong construct validity, among self-injuring individuals (Nock et al., 2007).

Adult Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5 (Adult-ADIS-5; Brown & Barlow, 2013)

The Adult-ADIS-5 was conducted at the screening visit to establish current mental disorders. This semi-structured diagnostic interview focuses on DSM-5 diagnoses of anxiety, depressive, trauma and stressor-related, obsessive-compulsive, somatoform, and substance use disorders. The ADIS has demonstrated excellent to acceptable interrater reliability for the anxiety and mood disorders (Brown, DiNardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Disorders (SCID-II; First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997)

The SCID-II is a semi-structured diagnostic interview used to determine the presence of personality disorders. It has demonstrated good psychometric properties and adequate convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity (e.g., Ryder, Costa, & Bagby, 2007), as well as good interrater reliability (e.g., Andover et al., 2014; Pistorello et al., 2012). In this study, only the BPD section was administered at the screening.

Daily assessment

NSSI was monitored continuously throughout all study phases via EMA methods, which reduce the recall biases associated with traditional self-report measures, augment ecological validity, and are ideal for obtaining information about sensitive behaviors (e.g., Nock et al., 2009; Shiffman, Stone & Hufford, 2008). A structured series of questions was administered through SymTrend, in which participants were first asked whether they had experienced an urge to engage in NSSI since their last entry. If they reported an urge, they were asked follow-up questions about the urge (e.g., duration, method considered), and whether they engaged in the behavior. If they reported a NSSI behavior, they were asked follow-up questions about the behavior (e.g., method). Participants were instructed to complete this assessment at least once per day and to self-initiate an entry whenever they experienced a NSSI urge or act.

Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS; Norman et al., 2006)

The OASIS, which is a five-item, continuous measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment, was administered weekly throughout the study. Higher scores on the OASIS indicate greater severity and impairment. Studies have indicated that the OASIS has high internal consistency, excellent test-retest reliability, and good convergent and discriminant validity among psychiatric outpatients (e.g., Campbell-Sills et al., 2009; Norman et al., 2013).

Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale (ODSIS; Bentley, Gallagher, Carl, & Barlow, 2014)

The ODSIS, which is a five-item instrument designed to measure the severity and impairment of depressive symptoms, was administered weekly. Higher ODSIS scores indicate greater severity and impairment. In its initial validation, the ODSIS evidenced excellent internal consistency, good convergent and discriminant validity, and discriminated between outpatients with and without a mood disorder (Bentley et al., 2014).

Southampton Mindfulness Questionnaire (SMQ; Chadwick et al., 2008)

The SMQ, a 16-item measure of mindful awareness of distressing thoughts and images, was administered weekly to assess mindful emotion awareness. Higher scores on the SMQ reflect greater levels of mindful awareness. The SMQ has demonstrated good internal validity and consistency in research with psychiatric outpatients (e.g., Boswell et al., 2014; Chadwick et al., 2008).

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire – Reappraisal (ERQ-R; Gross & John, 2003)

The ERQ is a 10-item measure assessing two ER strategies (cognitive reappraisal [ERQ-R] and expressive suppression [ERQ-S]) that was administered weekly. Higher scores on the ERQ-R indicate greater reappraisal use. Studies have demonstrated good internal reliability and discriminability between the two ERQ subscales among undergraduate and community-based samples (e.g., Gross & John, 2003; Moore, Zoellner, & Mollenholt, 2008).

Data Analysis

Analyses were conducted in accordance with established guidelines for SCED research and thus used a combination of visual inspection and statistical methods (Barlow et al., 2009; Tate et al., 2016). For visual inspection, primary outcome variables (NSSI urges and acts) were first plotted graphically for each participant.2 The effect of the interventions on NSSI was then evaluated by visually comparing the level, mean, and slope of weekly NSSI urges and number of NSSI acts during intervention and follow-up phases against the baseline phase. For participants who received both interventions, within-participant visual comparisons also included comparing the level, mean, and slope of weekly NSSI urges and number of acts during each intervention phase. The primary criterion used to determine clinically meaningful change was absence of self-injurious behavior after the intervention phase (or phases; Rizvi & Nock, 2008).

To complement visual inspection, Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to describe the overall phase effect on daily NSSI urges and acts within each participant. Bootstrapping resampling with replacement and maximum likelihood estimation were employed, and statistical significance was determined with the Monte Carlo p value. For participants who showed a significant overall effect, Mann-Whitney U tests were used to indicate which between-phase comparisons were driving the overall effect; a Bonferroni-correction was used for these analyses.3 To describe the effect of study phase on NSSI in the group as a whole, generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM) analyses were conducted with the glmer procedure in the R package, lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015; R Core Team, 2015). GLMM excludes missing data (here, days without observations for NSSI urges and acts) and builds equations based on all available data. Examination of distributions of both daily NSSI urges and acts indicated these data were decidedly non-normal and suggested Poisson distributions. Using the R vcd package (Meyer, Zeileis, & Hornik, 2015), we conducted goodness of fit tests to a Poisson distribution, which indicated perfect fits of the distributions in both cases. Therefore, a Poisson distribution response model in which daily NSSI urges and NSSI acts were predicted from dummy-coded study phases was computed. Significance of pairwise phase comparisons of the proportions of NSSI urges and NSSI acts reported during each phase was then examined using a Bonferroni-correction.4

Weekly scores on measures of secondary outcomes and treatment skills were plotted graphically and the level, mean, and slope of data during intervention and follow-up phases were compared against baseline using visual inspection. Significance of within-participant change (from the baseline to the end of the two intervention and follow-up phases) was evaluated by calculating a 95% CI around observed change scores to determine reliability of changes (see Au et al., in press); Jacobson and Truax’s (1991) method was used for calculating standard error of the difference (Sdiff). When this 95% CI did not include zero, change was considered statistically significant. Overall (group) standardized mean difference scores were also calculated to estimate magnitude of change on secondary outcomes and skills from baseline to each subsequent phase using a d-statistic developed for SCED studies (Shadish, Hedges, & Pustejobsky, 2014) and corresponding 95% CIs. See online supplementary material for more detail about these analyses.

Results

Primary Outcomes: NSSI

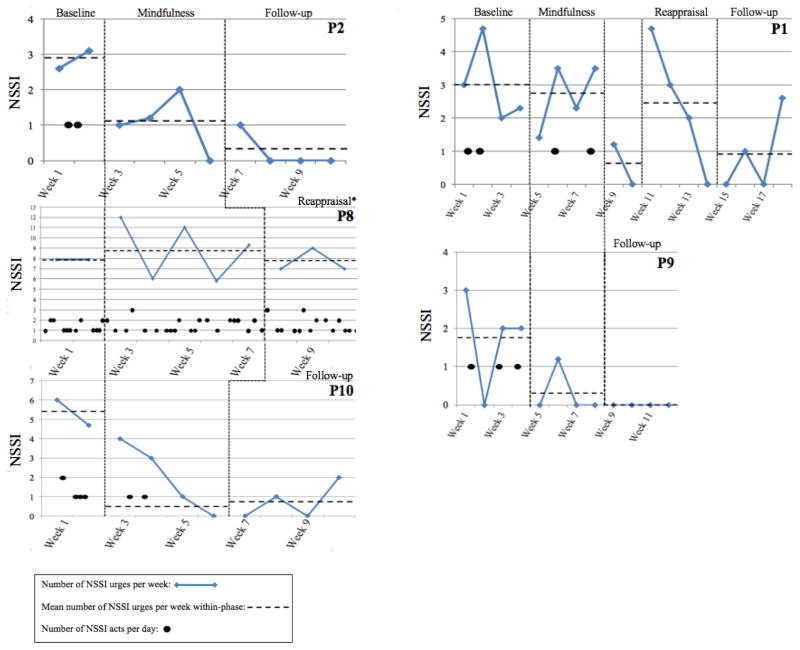

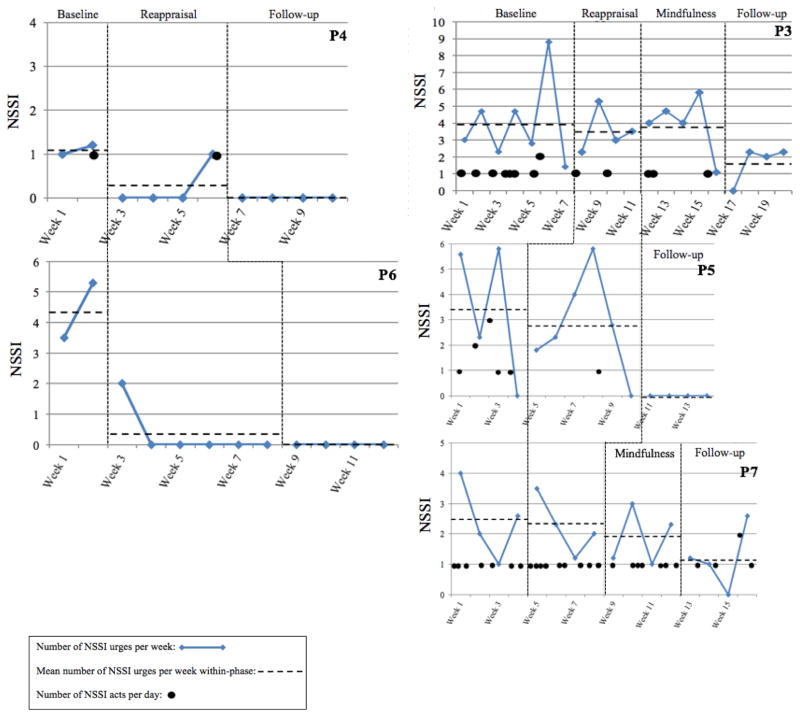

Overall, participants provided EMA data on 94.1% of days in the study, resulting in 5.9% missing daily NSSI data overall. Across participants, the greatest amount of missing daily data occurred during the baseline phase (10.5%) and the least during follow-up (5.3%). Between participants, missing daily data ranged from 0.0% (P8, P10) to 15.7% (P4). Graphs of NSSI urges and acts are displayed in Figure 2 (participants who received mindful emotion awareness first) and Figure 3 (participants who received reappraisal first). In each figure, participants are ordered according to baseline length. Six participants met the aforementioned criteria for response to the initial intervention; three received mindful emotion awareness (P2, P9, P10) and three received reappraisal (P4, P5,5 P6). Four participants met criteria for nonresponse to the initial intervention and thus the alternative intervention was also applied; two received mindful emotion awareness then reappraisal (P1, P8) and two received reappraisal then mindful emotion awareness (P3, P7).

Figure 2.

NSSI urges and acts: Participants assigned to receive mindful emotion awareness first. Participants assigned to the two-week baseline are in the first column and those assigned to the four-week baseline are in the second column. For P1, weeks 9 and 10 consisted of a two-week vacation taken by this participant during which no treatment sessions were conducted. P8’s five-week mindful emotion awareness phase spanned five weeks due to scheduling difficulties, but only four sessions. P8’s reappraisal phase also included behavioral activation and safety planning, as well as increased between-session contact.

Figure 3.

NSSI urges and acts: Participants assigned to receive cognitive reappraisal first. Participants assigned to the two-week baseline are in the first column and those assigned to the four-week baseline are in the second column. P3’s four-week baseline was extended due to scheduling difficulties for the first session. For P3, P5, and P6, intervention phases spanning more than four weeks still consisted of only four sessions.

Visual inspection of each participant’s baseline data indicates that there were no systematic, within-baseline phase improvements in NSSI urges or acts. For individuals assigned to mindful emotion awareness first (Figure 2), visual inspection of intervention phase data indicate that mindful emotion awareness was associated with clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI urges and acts for 3 of 5 participants (P2, P9, P10). For the other two participants (P1, P8), there were no clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI associated with this intervention. For P1, the adding cognitive reappraisal had a clinically meaningful effect on NSSI urges and acts, whereas for P8, there were no improvements associated with the application of the alternative intervention.6 For individuals assigned to receive cognitive reappraisal first (Figure 3), visual inspection of intervention phase data indicates clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI urges associated with this intervention for 2 of 5 participants (P4, P6). Data for NSSI acts during the intervention phase were less conclusive for P4 and P6, especially as P6 did not engage in NSSI during the study. Although for P5, cognitive reappraisal did not produce a systematic, clinically meaningful decrease in NSSI urges, this individual evidenced a clear reduction in NSSI acts during the intervention. For the remaining two participants assigned to cognitive reappraisal first (P3, P7), neither the initial intervention nor the addition of mindful emotion awareness training was associated with clear and systematic reductions in NSSI during active intervention phases.

Visual inspection of follow-up data7 indicates that for all six individuals who evidenced clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI during the first intervention phase, improvements were maintained or further enhanced. For individuals who received both interventions, data from the follow-up phase were more mixed. For P1, although NSSI urges were variable and the final data point overlapped with baseline, the mean level of NSSI urges during follow-up was lower than each previous study phase; P1 also did not engage in NSSI during the last ten study weeks. For P3, although NSSI urges overlapped with earlier phases, the level of mean weekly urges during follow-up phase was also lower than previous phases; this was also the only phase in which P3 reported no NSSI acts. For P7, however, weekly NSSI urges during follow-up overlapped with previous phases and there were no systematic trends, and NSSI acts were only slightly less frequent than previous phases. In summary, clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI occurred for 2 of the 3 participants who received both interventions and completed the follow-up phase.

Of the seven participants who completed the final interview, four denied NSSI since the study: P1 (two years out), P4 (20 months out), P5 (21 months out), P10 (three months out). At 26 months out, P2 estimated engaging in NSSI five times, and not within the past 1.5 years. At 16 months out, P7 estimated engaging in NSSI 15 times, which is notably less frequent NSSI than any study phase. At six months out, P9 estimated one NSSI act per month, which is less frequent than their study baseline, but more frequent than intervention or four-week follow-up phases.

Results from Kruskal-Wallis tests are presented in Table 2. For the five participants who demonstrated a statistically significant phase effect on NSSI urges and/or acts, a series of Mann-Whitney U tests were also conducted (see Table 3). Overall, these analyses suggest that overall phase effects were largely influenced by differences between baseline and follow-up phases.

Table 2.

Kruskal-Wallis Tests: Overall Phase Effects on NSSI Urges and Acts

| Test statistic | p | Mean rank: Baseline | Mean rank: Mindful emotion awareness | Mean rank: Cognitive reappraisal | Mean rank: Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received mindful emotion awareness training first | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Two-week baseline phase | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| P2 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(2) = 8.24 | < .05 | 43.18 | 35.88 | -- | 31.75 |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(2) = 6.45 | .05 | 39.18 | 35.00 | -- | 35.00 | |

| P8 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(2) = 0.78 | .68 | 34.19 | 36.98 | 32.38 | -- |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(2) = 0.18 | .91 | 36.13 | 34.00 | 35.75 | -- | |

| P10 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(2) = 6.47 | < .05 | 43.61 | 35.46 | -- | 31.48 |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(2) = 9.85 | < .01 | 42.57 | 34.96 | -- | 32.50 | |

|

| |||||||

| Four-week baseline phase | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| P1 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(3) = 4.39 | .23 | 56.12 | 55.12 | 51.43 | 44.31 |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(3) = 4.93 | .21 | 53.42 | 54.36 | 49.50 | 49.50 | |

| P9 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(2) = 9.29 | < .01 | 46.82 | 39.54 | -- | 38.00 |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(2) = 5.93 | .05 | 44.39 | 40.00 | -- | 40.00 | |

|

| |||||||

| Received cognitive reappraisal first | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Two-week baseline phase | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| P4 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(2) = 4.26 | .15 | 34.77 | -- | 31.15 | 30.00 |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(2) = 1.56 | .69 | 32.88 | -- | 31.65 | 30.50 | |

| P5 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(2) = 13.57 | < .01 | 45.00 | -- | 49.88 | 33.00 |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(2) = 10.74 | < .01 | 49.89 | -- | 41.70 | 40.50 | |

| P6 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(2) = 8.79 | < .05 | 49.38 | -- | 40.88 | 39.00 |

| NSSI acts/day | N/A | N/A | N/A | -- | N/A | N/A | |

|

| |||||||

| Four-week baseline phase | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| P3 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(3) = 3.07 | .38 | 63.99 | 63.88 | 64.06 | 52.38 |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(3) = 7.37 | .06 | 67.58 | 60.50 | 60.04 | 55.00 | |

| P7 | NSSI urges/day | χ2(3) = 2.56 | .46 | 58.91 | 56.53 | 58.94 | 49.80 |

| NSSI acts/day | χ2(3) = 2.18 | .55 | 57.67 | 55.78 | 60.10 | 50.84 | |

Table 3.

Mann-Whitney U Tests: Between-Phase Comparisons of NSSI Urges and Acts

| Baseline versus mindful emotion awareness | Baseline versus reappraisal | Baseline versus follow-up | Mindful emotion awareness versus follow-up | Reappraisal versus follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received mindful emotion awareness training first | |||||

|

| |||||

| Two-week baseline phase | |||||

|

| |||||

| P2 | |||||

| NSSI urges/day | U = 175.00, p = .12 | -- | U = 162.00, p = .01* | U = 321.00, p = .18 | -- |

| P10 | |||||

| NSSI urges/day | U = 150.00, p = .14 | -- | U = 128.50, p = .01* | U = 347.00, p = .28 | -- |

| NSSI acts/day | U = 153.00, p = .06 | -- | U = 140.00, p = .01* | U = 364.00, p = .50 | -- |

|

| |||||

| Four-week baseline phase | |||||

|

| |||||

| P9 | |||||

| NSSI urges/day | U = 299.00, p = .09 | -- | U = 308.00, p = .02 | U = 350.00, p = .48 | -- |

|

| |||||

| Received cognitive reappraisal training first | |||||

|

| |||||

| Two-week baseline phase | |||||

|

| |||||

| P5 | |||||

| NSSI urges/day | -- | U = 353.00, p = .46 | U = 238.00, p = .01* | -- | U = 280.00, p = .00* |

| NSSI acts/day | -- | U = 325.50, p = .02 | U = 252.00, p = .01* | -- | U = 476.00, p = 1.00 |

| P6 | |||||

| NSSI urges/day | -- | U = 132.00, p = .03 | U = 93.00, p = .04 | -- | U = 620.00, p = .51 |

Note. Only participants with significant overall phase effects are presented.

Statistically significant at the Bonferroni-corrected significance level of .017.

-- refers to phase comparisons that were not applicable as participant did not receive the intervention.

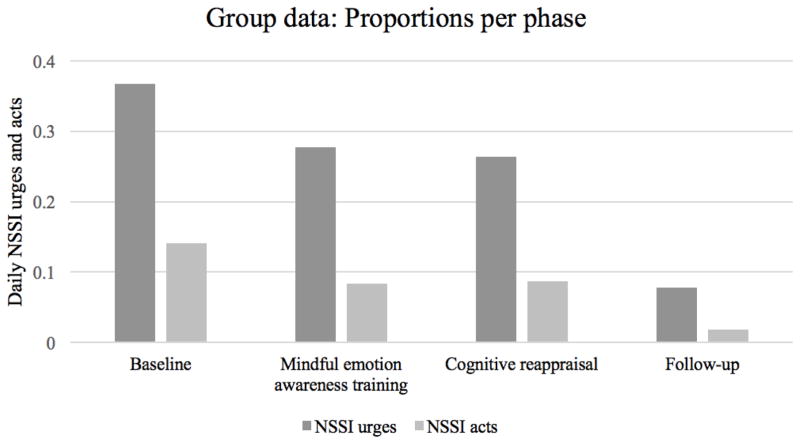

Glmer analyses indicated a significant overall effect of study phase on NSSI urges (Wald Chi-Square = 50.99, p < .0001). The proportions of NSSI urges by study phase and Bonferroni-corrected pairwise phase comparisons can be viewed in Table 4 and Figure 4. Pairwise phase comparisons indicated significantly smaller proportions of NSSI urges during the mindful emotion awareness, cognitive reappraisal, and follow-up phases compared to the baseline phase. The proportion of NSSI urges during the follow-up phase was significantly smaller than the three previous phases. The proportions of NSSI urges reported during each intervention phase were not significantly different. Glmer analyses also showed a significant overall phase effect on NSSI acts (Wald Chi-Square = 46.34, p < .0001). As can be seen in Table 4 and Figure 4, pairwise phase comparisons showed significantly smaller proportions of NSSI acts during the mindful emotion awareness, cognitive reappraisal, and follow-up phases compared to the baseline phase. The proportion of NSSI acts during follow-up was also significantly smaller than all previous phases. There were no significant differences in NSSI acts between the two intervention phases.8

Table 4.

Proportions of NSSI Urges and Acts by Phase and Bonferonni-Corrected Pairwise Phase Comparisons

| Baseline | Mindful emotion awareness | Cognitive reappraisal | Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSSI urges | 0.367 | 0.277a | 0.264a | 0.078b |

| NSSI acts | 0.141 | 0.083a | 0.087a | 0.018b |

Note. Group data are based on N = 855 daily observations. Statistical significance of pairwise phase comparisons was determined using a Bonferroni-correction.

Significantly smaller proportion than the baseline phase.

Significantly smaller proportion than the baseline, mindful emotion awareness training, and cognitive reappraisal phases.

Figure 4.

Group data based on N = 855 daily observations. Bars indicate proportions of NSSI urges and acts per phase. Pairwise phase comparisons showed statistically significant differences between proportions of NSSI urges and NSSI acts in the baseline phase compared to all three subsequent phases (baseline > all other phases), and the follow-up phase compared to all three previous phases (follow-up < all other phases). There were no differences between the two intervention phases.

Secondary Outcomes and Treatment Skills

Graphs of secondary outcomes and treatment skills are available in Supplementary Figures S1–S10. Change scores and 95% CIs are available in Supplementary Table S1. Visual inspection indicates that six participants experienced clinically meaningful reductions in anxiety after the interventions were introduced; changes in anxiety were statistically reliable for four participants. Five participants experienced clinically meaningful and statistically reliable reductions in depression, whereas three participants showed reliable increases in depression.

Nine participants demonstrated clinically meaningful and/or statistically reliable changes in at least one of the two therapeutic skills by the follow-up phase, if not also during active intervention phases. Only two participants provided clear evidence for intervention specificity of change (i.e., greater changes occurring only in the skill that each intervention intends to address) based on visual inspection of changes in levels of mindful emotion awareness and reappraisal. Of the seven participants who evidenced reliable increases in mindful emotion awareness from baseline to follow-up, five received mindful emotion awareness training and two only received the cognitive reappraisal intervention. Of the five participants who evidenced reliable increases in reappraisal by follow-up, four received cognitive reappraisal and only one received mindful emotion awareness training. Of the six participants who received only one intervention, three showed reliable change in only the targeted skill and three showed reliable change in both skills.

Group descriptive statistics and effect sizes for secondary outcomes and treatment skills by study phase are presented in Supplementary Table S2. The most desirable scores on all self-report measures were observed during the follow-up phase. Baseline to follow-up phase comparisons indicate moderate to large, significant effects on anxiety and depression in the sample as a whole. Baseline to follow-up phase comparisons also indicate large, significant increases in mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal. CIs corresponding to all effect sizes for treatment skills were overlapping, suggesting that neither intervention was associated with significantly greater improvements in the targeted skill over the non-targeted skill.

Discussion

This study used a counterbalanced, combined series (multiple baseline and data-driven phase change) SCED to examine the effects of two transdiagnostic interventions (mindful emotion awareness training and cognitive reappraisal) on NSSI. For 8 of 10 participants, four weeks of mindful emotion awareness and/or four weeks of reappraisal produced clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI. Six of 10 participants showed clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI after only one intervention, whereas for two participants, the combined impact of both interventions resulted in clinically meaningful change. Of the five participants who continued to experience urges during the four-week follow-up phase, only one engaged in NSSI. There were no readily apparent differences between the two interventions in terms of magnitude or speed of changes. These findings provide support for hypotheses in the majority of cases (8 of 10).

Statistical test results generally corroborated those gleaned from visual inspection, as 5 of 10 participants demonstrated statistically significant between-phase differences in NSSI. In the sample as a whole, NSSI urges and acts were less frequent after the interventions were introduced; effects were strongest when comparing the follow-up to baseline. The lack of systematic improvement during two- and four-week baseline phases, reductions in NSSI only after introducing the interventions, and magnitude of changes suggest that the observed effects are likely not due to chance fluctuations, regression to the mean, spontaneous recovery, life events, or passage of time. Information from a longer-term follow-up provide preliminary indication that gains were generally maintained over time. Overall, results suggest that interventions comprising 4 to 8 weekly, sessions focused on specific emotion-focused strategies may be efficacious for NSSI.

Two participants did not experience meaningful changes in NSSI during the study. There are several possible reasons for this nonresponse. First, these two individuals engaged in NSSI more frequently than most other participants, which suggests that for adults engaging in NSSI more regularly (e.g., almost daily cutting for P8), these low-intensity interventions alone may not be sufficient. Second, one of these participants (P8) had the most complex clinical presentation, meeting criteria for nine current diagnoses (sample mean = 3.3). After a significant life stressor at the beginning of the first intervention, suicidal ideation quickly escalated to intense, active levels, and this individual was later withdrawn to facilitate a hospitalization. Entering a higher level of care may have been preferable when suicidal thoughts first escalated for P8; further, this individual likely would have benefitted from more flexible, multifaceted treatment to address their range of clinical problems (e.g., social skills training, trauma-focused procedures), in addition to the behavioral activation and safety planning components included during the reappraisal phase. Third, P8 evidenced the lowest baseline levels of mindful emotion awareness and reappraisal, which suggests that a higher treatment dose may be necessary when more extreme emotion regulation deficits are present. P7 and P8 also displayed lower motivation to change NSSI; thus, motivational enhancement strategies may have been helpful in these cases.

Findings for secondary outcomes (i.e., anxiety, depression) were positive overall, yet somewhat more mixed at the single-case level than those for NSSI outcomes. This may reflect the fact that interventions were tailored to NSSI and not extended to co-occurring emotional disorders and symptoms. Results also indicate that the interventions successfully targeted their hypothesized skills-based mechanisms: increased mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal. Eight of the 9 participants who showed increased mindful emotion awareness and/or reappraisal during the study also showed clinically meaningful reductions in NSSI. Overall, these results suggest that mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal may be effective strategies to deliver during NSSI treatment; however, whether these skills functioned as true mechanisms of action is less clear. For 7 of 8 participants who showed reductions in NSSI, consistent increases in these skills did not clearly precede changes in self-injury. More research is needed to further examine whether changes in these constructs occur before and uniquely predict reductions in NSSI (and not vice-versa), and clarify the key mechanisms of change during successful NSSI treatment.

The highest levels of mindful emotion awareness and reappraisal were observed after active intervention phases. These findings suggest that it may take more than four weeks of practice for these skills to take hold, and to result in meaningful differences in NSSI. Along these lines, there is literature to indicate that negative affect may increase during early stages of mindfulness practice, whereas continued use of mindful awareness reduces negative emotions and related symptoms over time (e.g., Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015). It follows that although being more mindful of emotional experiences on an ongoing basis may reduce NSSI over time, providing patients with more concrete skills to use when experiencing severe self-injurious urges is necessary. Such deliberate strategies (e.g., distraction, crisis coping) can be framed as important for prioritizing safety and reducing distress to a manageable level, at which time a nonavoidant strategy (e.g., mindfulness, opposite action, problem-solving) may be used.

Overall, there was not strong evidence for intervention specificity of change. These results align with other research indicating that specific therapeutic components do not necessarily have the biggest impact on only the specific construct that strategy is intended to address (e.g., Boswell et al., 2014; Peris et al., 2014). This also begs the question of whether mindful awareness and reappraisal share similar underlying mechanisms (e.g., Hayes-Skelton & Graham, 2012) and thus serve the same therapeutic function. Both interventions were extracted from the UP, which uses five core modules to target one underlying change mechanism: extinction of distress in response to intense emotion. Even if these two strategies engage the same mechanism, however, some individuals may be more receptive and/or evidence a stronger response to one over the other. Although this study did not show a clear advantage for either intervention, whether the four individuals who did not respond to the initial intervention would have shown stronger or more rapid changes if the other had been delivered first is unknown. Idiographic research that examines personalized selection and ordering of treatment components, coupled with improved knowledge of key mechanisms, should ultimately maximize treatment efficacy, and facilitate dissemination of efficient and cost-effective approaches for NSSI.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the study lacked an active control condition (e.g., treatment as usual) which means that the observed effects could be due to non-specific therapeutic contact and/or more clinician contact during the intervention phase(s). Future SCED research could benefit from standardizing the amount of clinician-participant contact across baseline and intervention phases. Second, all treatment and assessments were conducted by the same person. Third, the study used measures of mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal that do not map precisely onto these constructs as they are delivered within the UP. In light of observed discrepancies regarding the relationship between NSSI and self-report versus non-self-report measures of emotion regulation processes (e.g., Franklin et al., 2010), future research that uses multi-method and ecologically valid assessments of mindful awareness and reappraisal may help shed light on the exact mechanisms of these interventions. Fourth, participants were provided monetary compensation for completion of study procedures, which may affect generality of findings to more typical clinical settings. Another limitation is potential for generality to more diverse and severe self-injuring populations, as participants were largely female and Caucasian young adults with relatively low-frequency and severity NSSI, and higher-risk individuals were excluded. Thus, findings must be considered within the context of the lower-risk sample and in fact, provide some indication that weekly, emotion-focused interventions may not be sufficient stand-alone treatments for more severe self-injuring individuals with imminently life-threatening symptoms.

Despite these limitations, the use of a sample with less severe self-injurious thoughts and behaviors (overall) rendered it possible to conduct a well-controlled exploration of core, mechanistic treatment strategies for NSSI, as most participants did not require shifting the focus of treatment to safety. The rigorous and practical experimental methodology, continuous measurement, and use of EMA/EMI were also strengths of the study. The idiographic design also allowed for exploration of individual factors that influenced response. Overall, results suggest that delivering these interventions in isolation may be better suited for individuals with less frequent and acute NSSI. Within a stepped-care model for NSSI, skills-based interventions may be appropriate first-line treatments for lower-risk self-injuring individuals, whereas more chronic, acute patients could be “stepped up” to more intensive, costly care. Given the rising rates of NSSI on college campuses (e.g., Center for Collegiate Mental Health, 2016), university health centers facing high demand for services may benefit from this model.

Conclusions

In conclusion, results from the present study indicate that brief, cognitive-behavioral interventions targeting two specific therapeutic skills (mindful emotion awareness and cognitive reappraisal) that directly address the functional processes that often maintain self-injury may reduce NSSI. Future research is needed to determine the optimal use of transdiagnostic, emotion-focused interventions within evidence-based models of care for NSSI.

Supplementary Material

Public Health Impact Statement.

This study provides preliminary evidence that brief, emotion-focused interventions focused on increasing mindful awareness of emotions and/or flexibility in thoughts about emotion-producing situations may reduce nonsuicidal self-injury.

Footnotes

Participants who evidenced a partial response (between 25 and 50% reduction in average number of NSSI urges and acts per week or a ≥ 50% reduction in average number of NSSI urges or acts per week from baseline) were to return to a two-week baseline before the other intervention and follow-up; however, no participants met this criterion in the study, which may be due to our pre-determined criteria for a partial response being too narrow or stringent.

For ease of graphical interpretation, daily NSSI urges were aggregated to produce data points indicating number of urges per week. When phases were not evenly divisible into weeks (e.g., a 15-day baseline phase) and/or participants neglected to complete a daily entry, the total number of NSSI urges reported that week was divided by the number of days with data over seven.

As each participant included in these tests completed only one intervention phase, three between-phase comparison tests were conducted simultaneously; thus, significance was evaluated at .017 (typical p value of .05 divided by three) to reduce likelihood of Type I error.

Four between-phase tests were run for these analyses; thus, significance was evaluated at .013 (.05 divided by 4) to reduce likelihood of Type I error.

P5 was initially classified as responding to the first intervention due to reporting self-injurious urges during baseline that were later determined to be suicidal in nature. When these suicidal urges were later removed from the total number of baseline NSSI urges, P5 no longer met response criteria. Given that P5’s reduction in NSSI acts exceeded the 50% threshold and there were no NSSI urges during the last five study weeks, the second intervention was never applied.

Due to P8’s worsening suicidal ideation and depression, their reappraisal phase also included safety planning, behavioral activation, and increased between-session contact with the therapist.

P8 was withdrawn from the study after the seventh treatment session, so follow-up phase data were available for nine participants.

Glmer analyses were also computed without P8 (who was withdrawn before follow-up) for completeness. All overall phase effect and all pairwise comparisons reported for NSSI acts and urges remained statistically significant at (at least) p < .05.

References

- Allen KA, Hooley JM. Inhibitory control in people who self-injure: Evidence for impairment and enhancement. Psychiatry Research. 2014;225(3):631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson NL, Crowther JH. Using the experiential avoidance model of non- suicidal self-injury: Understanding who stops and who continues. Archives of Suicide Research. 2012;16(2):124–134. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.667329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andover MS, Morris BW. Expanding and clarifying the role of emotion regulation in nonsuicidal self-injury. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;59(11):569–575. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andover MS, Schatten HT, Morris BW, Miller IW. Development of an intervention for nonsuicidal self-injury in young adults: An open pilot trial. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2014;22(4):491–503. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews T, Martin G, Hasking P, Page A. Predictors of continuation and cessation of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au TM, Sauer-Zavala S, King MW, Petrocchi N, Barlow DH, Litz BT. Compassion-based therapy for trauma-related shame and posttraumatic stress: Initial evaluation using a multiple baseline design. Behavior Therapy. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.012. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Farchione TJ, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Boisseau CL, Allen LB, Ehrenreich-May J. Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders: Therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Nock MK, Hersen M. Single case experimental designs: Strategies for studying behavior change. 3. Boston, MA: Pearson; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bates M, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 2015;67(1):1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Gallagher MW, Carl JR, Barlow DH. Development and validation of the Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale. Psychological Assessment. 2014;26(3):815–830. doi: 10.1037/a0036216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson N, Carmody J, … Devins G. Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:230–241. doi: 10.1092/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JF, Anderson LM, Barlow DH. An idiographic analysis of change processes in the Unified Transdiagnostic Treatment of Depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(6):1060–1071. doi: 10.1037/a0037403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:609–620. doi: 10.1037/h0080369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-5 (ADIS-5) New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, DiNardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110(1):49–58. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Rudd DM, Wertenberger E, Young-McCaughon S, Peterson A. Nonsuicidal self-injury as a prospective predictor of suicide attempts in a clinical sample of military personnel. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2015;59:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Ellard KK, Barlow DH. Incorporating emotion regulation into conceptualizations and treatments of anxiety and mood disorders. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Norman SB, Craske MG, Sullivan G, Lang AL, Chavira DA, … Stein MB. Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: The Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;112:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Collegiate Mental Health. 2015 Annual Report (Publication No. STA 15–108) 2016. Jan, [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick P, Hember M, Symes J, Peters E, Kuipers E, Dagnan D. Responding mindfully to unpleasant thoughts and images: Reliability and validity of the Southampton Mindfulness Questionnaire (SMQ) British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;47:451–455. doi: 10.1348/014466508X314891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown M. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-injury: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:371–394. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Kaszniak AW. Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. American Psychologist. 2015;70(7):581–592. doi: 10.1037/a0039512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Tull MT, Gratz KL. Self-injurious behaviors in posttraumatic stress disorder: An examination of potential moderators. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;166:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, (SCID-II) Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Fox KR, Franklin CR, Kleiman EM, Ribeiro JD, Jaroszewski AC, … Nock MK. A brief mobile app reduces nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injury: Evidence from three randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1037/ccp0000093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Hessel ET, Aaron RV, Arthur MS, Heilbron M, Prinstein MJ. The functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: Support for cognitive-affective regulation and opponent processes from a novel psychophysiological paradigm. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119(4):850–862. doi: 10.1037/a0020896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EG, Hanley A, Farb NA, Froeliger BE. State mindfulness during meditation predicts enhanced cognitive reappraisal. Mindfulness. 2015;6(2):234–242. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Franklin JC, Nock MK. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44:1–29. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, Levy RL. Randomized controlled trial and uncontrolled 9-month follow-up of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality pathology. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44:2099–2112. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Gunderson JG. Preliminary data on acceptance-based emotion regulation group intervention for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT. Extending research on the utility of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality pathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2:316–326. doi: 10.1037/a0022144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Jazaieri H. Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2(4):387–401. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(2):348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. doi:0.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Skelton SA, Graham J. Decentering as a common link among mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal, and social anxiety. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2012;41:317–328. doi: 10.1017/S1352465812000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath NL, Carsley D, De Riggi M, Mills D, Mettler J. The relationship between mindfulness, depressive symptoms and non-suicidal self-injury amongst adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research. 2016;20(4):635–649. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1162243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron KE, Smyth JM. Ecological momentary interventions: Incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2010;15(Pt 1):1–39. doi: 10.1348/135910709X466063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe-Martin LA, Murrell AR, Guarnaccia CA. Repetitive nonsuicidal self-injury as experiential avoidance among a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68(7):809–829. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(1):12. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliem S, Kroger C, Kosfelder J. Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis using mixed-effects modeling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:936–951. doi: 10.1037/a0021015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Muehlenkamp JJ. Self-injury: A research review for the practitioner. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63(11):1045–1056. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, … Lindenboim N. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:757. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Cozza C. Behaviour therapy for nonsuicidal self-injury. In: Nock MK, editor. Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. pp. 221–250. [Google Scholar]

- Martinovich Z, Saunders S, Howard K. Some comments on “Assessing clinical significance”. Psychotherapy Research. 1996;6(2):124–132. doi: 10.1080/10503309612331331648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, Guimond T, Cardish RJ, Korman L, Streiner DL. A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(12):1365–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D, Zeileis A, Hornik K. vcd: Visualizing Categorical Data. R package version 1. 4–1. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Zoellner LA, Mollenholt N. Are expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal associated with stress-related symptoms? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najmi S, Wegner DM, Nock MK. Thought suppression and self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(8):1957–1965. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Jr, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatric Research. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. The Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self- mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ, Sterba SK. Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: A real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:816–827. doi: 10.1037/a0016948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Allard CB, Trim RS, Thorp SR, Behrooznia M, Masino TT, Stein MB. Psychometrics of the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) in a sample of women with and without trauma histories. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2013;16:123–129. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman SB, Cissell SH, Means-Christensen AJ, Stein MB. Development and validation of an overall anxiety severity and impairment scale (OASIS) Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23:245–249. doi: 10.1002/da.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasieczny N, Connor J. The effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy in routine public mental health settings: An Australian controlled trial. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2011;49:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Compton SN, Kendall PC, Birmaher B, Sherrill J, March J, … Piacentini J. Trajectories of change in youth anxiety during cognitive-behavior therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;83(2):239–252. doi: 10.1037/a0038402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistorello J, Fruzzetti AE, MacLane C, Gallop R, Iverson M. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) applied to college students: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(6):982–994. doi: 10.1037/a0029096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2015. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Costa PT, Bagby R. Evaluation of the SCID-II personality disorder traits for DSM IV: Coherence, discrimination, relations with general personality traits, and functional impairment. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:626–637. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Bender TW, Gordon KH, Nock MK, Joiner TE., Jr Non- suicidal self-injury (NSSI) disorder: A preliminary study. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2012;3(2):167. doi: 10.1037/a0024405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR. Software for Meta-analysis of Single-Case Design DHPS version March 7–2015. 2015 Retrieved February 1, 2016 from http://faculty.ucmerced.edu/wshadish/software/software-meta-analysis-single-case-design/dhps-version-march-7-2015.

- Shadish WR, Hedges LV, Pustejovsky JE. Analysis and meta-analysis of single-case designs with a standardized mean difference statistic: A primer and applications. Journal of School Psychology. 2014;52(2):123–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, St John NJ. Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2014;44(3):273–303. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate R, Perdices M, Rosenkoetter U, McDonald S, Togher L, Shadish W, … Vohra S. The Single-Case Reporting Guideline in Behavioural Interventions (SCRIBE) 2016: Explanation and Elaboration. Archives of Scientific Psychology. 2016;4:10–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tatnell R, Kelada L, Hasking P, Martin G. Longitudinal analysis of adolescent NSSI: The role of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42:885–896. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Austin SB, Chapman AL. Treating nonsuicidal self-injury: A systematic review of psychological and pharmacological interventions. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;59(11):576–585. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon D, Hasking P, Martin G. The roles of emotion regulation and ruminative thoughts in non-suicidal self-injury. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014a;53:95–113. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon D, Hasking P, Martin G. Change in emotion regulation strategy use and its impact on adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: A three-year longitudinal analysis using latent growth modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014b;123(3):487–498. doi: 10.1037/a0037024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyear I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the adolescent depression antidepressants and psychotherapy trial (ADAPT) American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wupperman P, Fickling M, Klemanski DH, Berking M, Whitman JB. Borderline personality features and harmful dysregulated behavior: The mediational effect of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69(9):903–11. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.