Highlights

-

•

Alveolar Echinococcosis is a rare but potentially fatal parasitic infection primarily affecting liver.

-

•

The diagnosis and treatment can be difficult and clinical misinterpretation as malignancy is not rare.

-

•

The principal treatment of Alveolar Echinococcosis is surgery accompanied with chemotherapy.

Keywords: Hydatid disease, Echinococcus multilocularis, Alveolar echinococcosis, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Human Alveolar Echinococcosis – Alveolar Hydatid disease (AE) is an omitted zoonotic infection presenting with focal liver lesions. Cause of AE is a larval stage of Echinococcus multilocularis tapeworms.

Case presentation

In this report an extraordinary case of a 38 year-old female examined due to 2 liver tumors and 2 pulmonary nodules is described. The patient underwent pulmonary and liver surgery for suspected advanced cholangiocellular carcinoma and surprisingly AE was found.

Discussion

Distinguishing intrahepatic AE from other focal liver lesion can be complicated and in many cases is diagnosed incorrectly as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or other liver malignancy.

Conclusion

AE is a rare but potentially fatal parasitic infection primarily affecting liver, although it can metastasise to lung, brain and other organs. The diagnosis and treatment can be difficult and clinical misinterpretation as malignancy is not rare. The principal treatment of AE is surgery accompanied with chemotherapy.

1. Introduction

Echinococcosis is a heterogenic group of zoonotic parasitic diseases caused by the cestode tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus or less frequently by Echinococcus multilocularis. Humans are an accidental intermediate host [1]. The Czech Republic, unlike our neighboring countries, is not an endemic area of echinococcosis and hydatid disease is rare and mostly imported infection [2]. According to the SCARE criteria [3], we report an extraordinary case of a 38 year-old female who was examined and underwent surgery for suspected advanced cholangiocellular carcinoma with surprising final diagnosis of Human Alveolar Echinococcosis (AE).

2. Case presentation

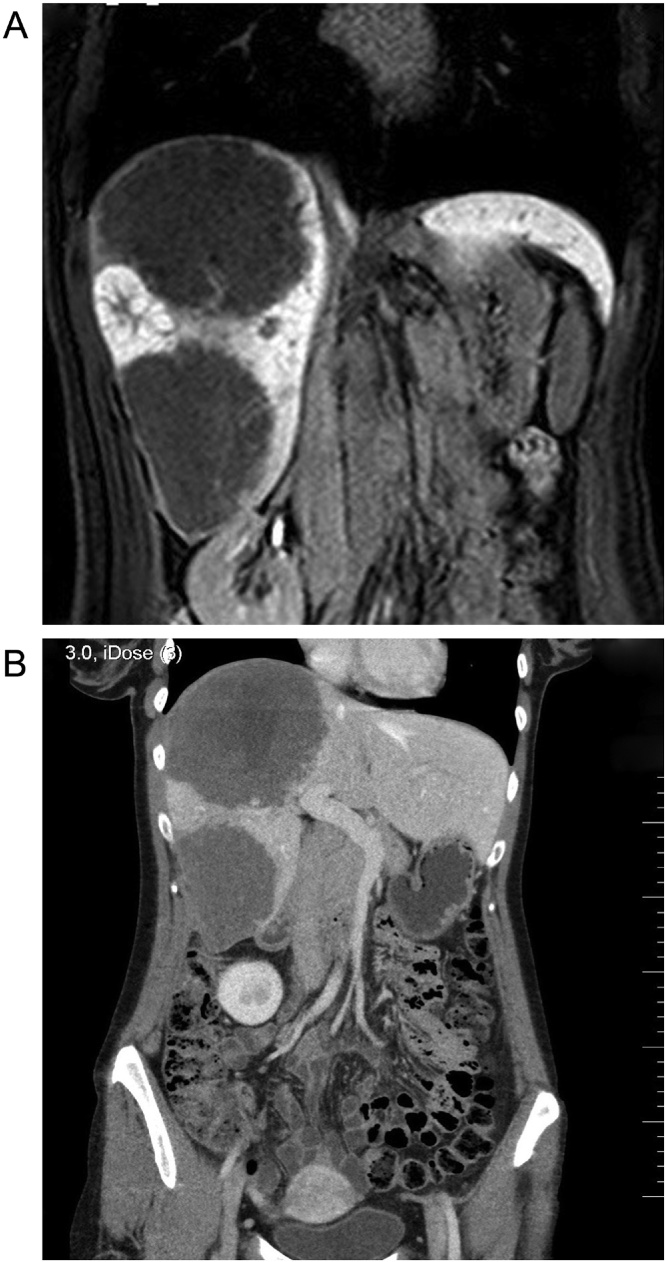

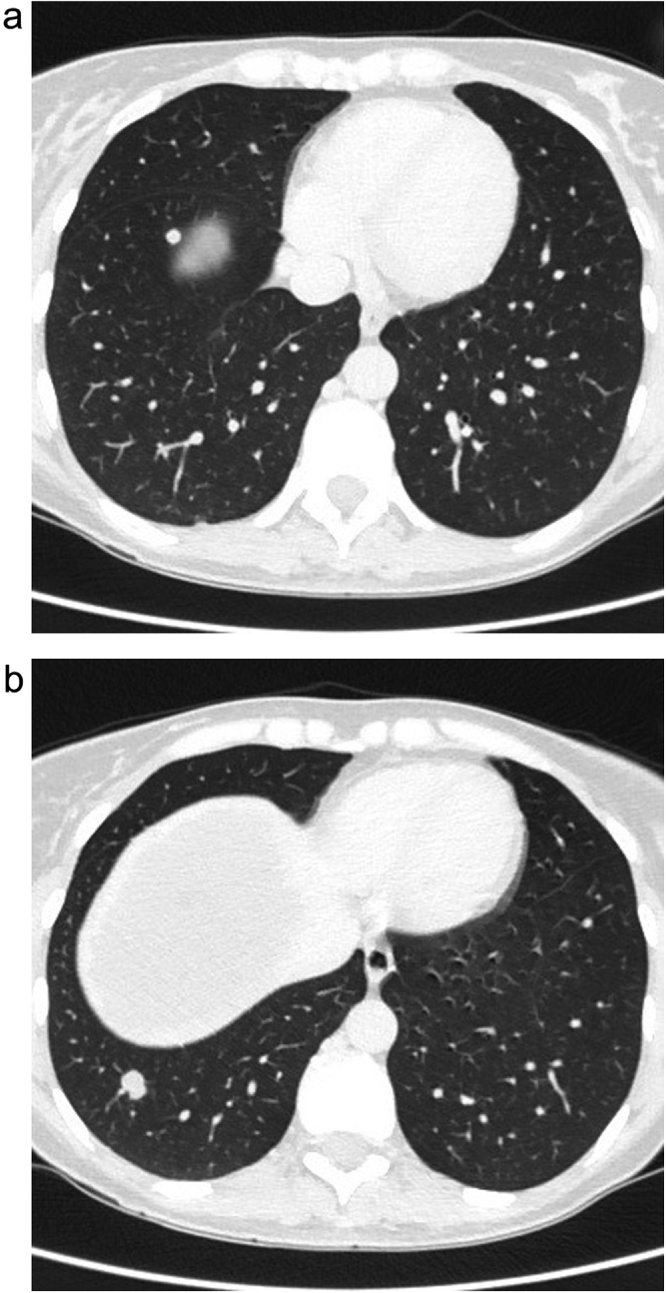

A 38 year-old female was examined in regional hospital in June and July 2015 due to accidental US finding of 2 liver tumors. In consequent abdominal MRI and CT were found 2 atypical voluminous tumors in the right liver lobe. Imaging methods identified large tumors in segment S7/8 measuring 135 × 95 mm and in segment S5/6 measuring 114 × 75 mm suspected to be a malignancy. Another finding was a mass of focal nodular hyperplasia 45 × 32 mm between the tumors. (Fig. 1) Both tumors were biopsied with CT navigation, and histopathology was interpreted as suspected cholangiocellular carcinoma. In August 2015, the patient was presented to our surgery department. The patient’s laboratory results demonstrated no abnormality. Additional CT of thorax showed 2 lung nodules measuring 12 respectively 8 mm in the right lower lobe suspected to be metastasis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

(a) MRI scan – 2 tumors in the right liver lobe and a mass of focal nodular hyperplasia between the tumors. (b) CT scan – 2 atypical voluminous tumors in the right liver lobe.

Fig. 2.

a,b: CT scan – 2 lung nodules in the right lower lobe.

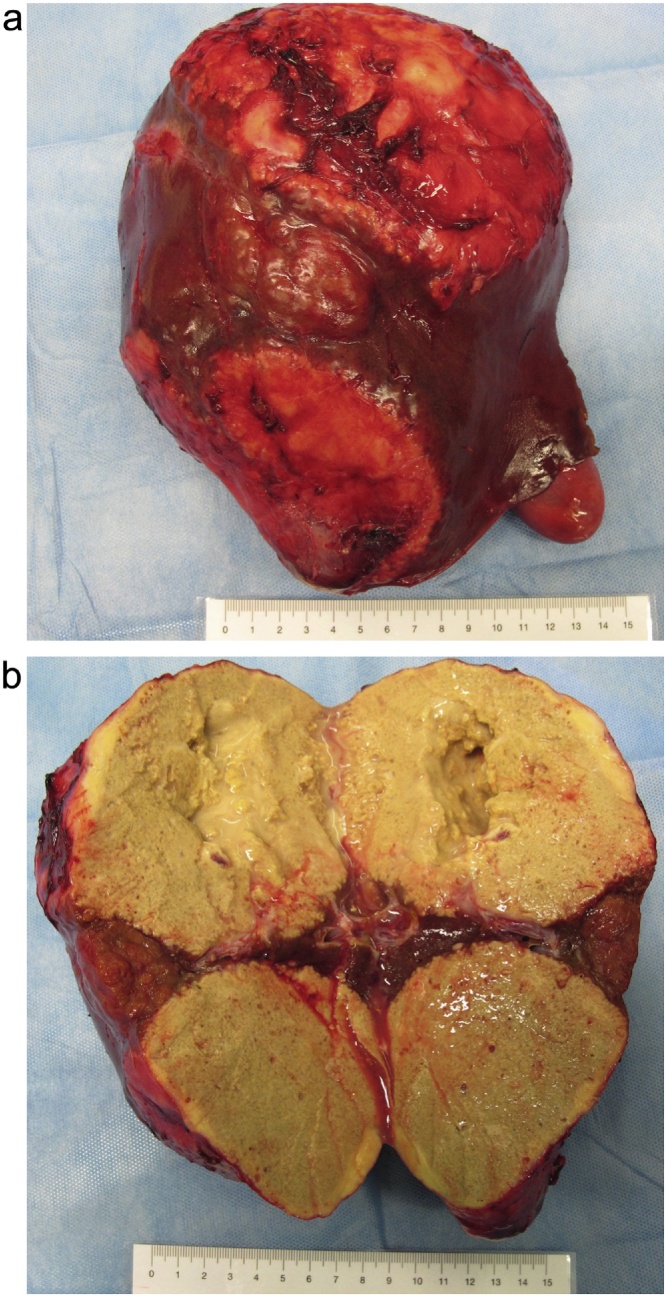

A decision of primary resection of pulmonary nodules was made, and in September 2015 patient underwent VATS non-anatomical resection of both nodules. Histopathologic examination showed necrotic tissue and nonspecific granulation tissue with no finding of malignancy. The decision of multidisciplinary team in the aspect of the excellent performance status and particularly young age of the patient were to provide a right hepatic lobectomy, and the patient underwent surgery in October 2015 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

a,b: Resected right lobe of the liver with tumors.

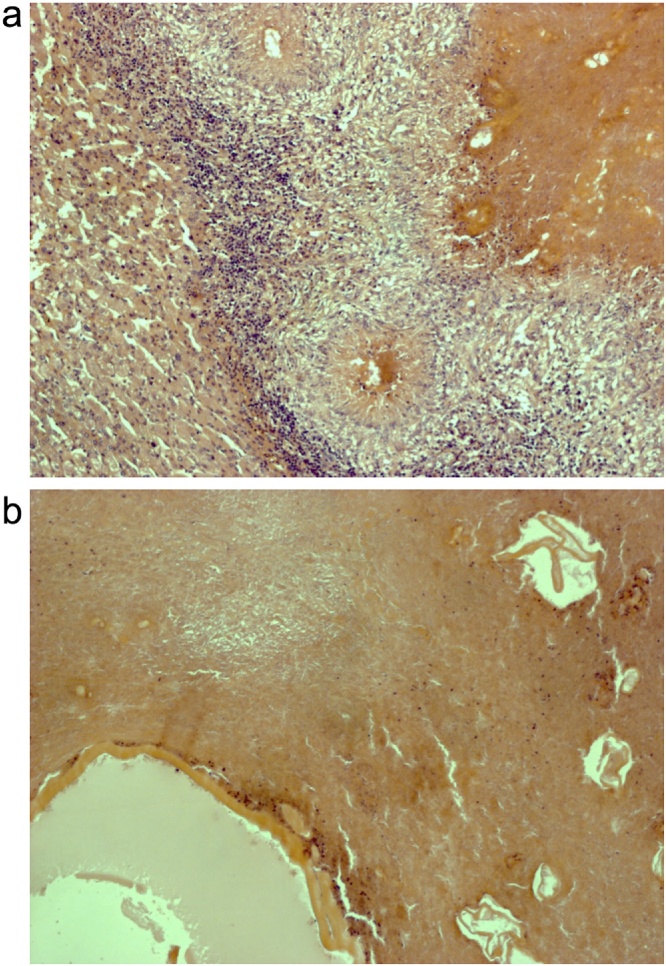

Pathologic findings described two solid tumors with light gray-brown color with diameter 125 × 144 × 90 mm and 125 × 76 × 82 mm. Histopathologic findings were identical in both tumor and showed an extensive necrosis of liver tissue that was lined with nonspecific granulation tissue. In the necrosis there were multiple optically empty spaces with various sizes. This material was positive to PAS dyeing, and to Grocott silver staining (Fig. 4). Additional pathological examinations were performed, and in several cavities the presence of parasitic structures, subsequently identified as the larval stage of Echinococcus multilocularis was found.

Fig. 4.

(a) Extensive necrosis of liver tissue lined with nonspecific granulation tissue (Hematoxyline-eosin, 160x). (b) Necrosis of liver tissue with multiple optically empty spaces (Hematoxyline-eosin, 160×).

The patient recovered from the surgery, and following serological examination confirmed the presence of Echinococcus multilocularis infection. Antiparasitic chemotherapy with albendazol was implemented. 15 months after surgery the patient is in good condition without any signs of persistent infection.

3. Discussion

Hydatid disease (echinococcosis) is a zoonotic parasitic infection affecting human and mammal viscera caused by larval stage of tapeworms genus Echinococcus. Echinococcus which is spread worldwide. The most occurring specie is Echinococcus granulosus, which causes cystic hydatidosis. In the Northern hemisphere (Central and Northern Europe, Asia and North America) there is a related specie Echinococcus multilocularis, causing AE. The Czech Republic is not an endemic area of Echinococcus multilocularis. It was first reported in by Bartos [4] in 1928. Only 20 cases of human AE were reported during 199–2014 [1], [2], [4].

Echinococcus multilocularis lives in the small intestines of carnivores, firstly dogs, cats and foxes. Intermediate hosts are small mammals, primarily rodents. A person can become infected by ingesting eggs occasionally, or by direct contact with dogs or cats and that can run around freely in nature and catch infection from the rodent [5], [6], [7].

Symptomatology of AE depends on the affected organ, cyst size and location of the cyst expanding interaction with adjacent organs.

AE most often affects the liver (98% of all cases), and infection is usually clinically silent for many years. The clinical symptoms usually develop after a long incubation period (5–15 years) causing considerable diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties [7], [8]. Large cysts resemble invasively growing tumor and may cause abdominal pain, the development of jaundice, liver vein, trombosis or portal hypertension. AE can infect lung, brain and other organs [9], [10], [11]. Without treatment, 70% of patients die within 5 years and 90% within 10 years of diagnosis [12], [13].

The first diagnostic utility is abdominal ultrasound or computer tomography. Imaging confronts physician with unsuspected findings. In 70% the characteristic calcifications are present, and in 70% the detectable necrotic areas with cavities [6], [8], [14] are present. The effectiveness of 18F-FDG PET/CT and delayed 18F-FDG PET/CT was already demonstrated for the follow-up of patients with AE but it can also facilitate the initial diagnostics [15], [16].

Eosinophillia is present just in 10% patient with AE. Serological examination with specific IgG antibodies detection by ELISA method confirms diagnosis in the majority of patients. The diagnosis is confirmed by finding of parasitic masses in the histopathological examination [1], [6], [8], [17].

Distinguishing intrahepatic AE from other focal liver lesion can be complicated. In the differential diagnosis it is necessary to consider metastatic adenocarcinoma and other primary liver tumours, and also benign liver lesions such as hemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular adenoma [18], [19].

In our case there was misinterpretation of advanced cholangiocellular carcinoma based on imaging of infiltrative liver lesions with pulmonary metastasis and false histopathologic diagnosis from liver biopsy, which was initially described as suspected cholangiocellular carcinoma. Later it was reconsidered as necrotic tissue. In 2015 Stojkovic reported that up to one-third of treatment decisions were based on misinterpretation where liver AE was diagnosed incorrectly, and almost one-half of these patients were mistakenly diagnosed for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or other liver malignancy [8].

The principal treatment of AE is surgery and chemotherapy. Surgery is the first-choice option in all operable patients. Radical resection of the entire parasitic lesions is the only curative procedure [1], [6]. Albendazol and praziquantel chemotherapy should be carried pre-, peri- and postoperatively to reduce the risk of anaphylaxis and recurrence. Chemotherapy should be carried out for at least 2 years after surgery (lifelong in certain patients) and patient should be monitored for at least 10 years [6], [7], [12], [13], [20].

4. Conclusion

AE represents uncommon but severe, potentially fatal and often misdiagnosed parasitic disease. Diagnosis depends on imaging methods, serology and histopathologic findings. Therapy is based on the radical surgery supplemented pre- and postoperative deployment antiparasitic chemotherapy. Treatment of patients with AE requires close multidisciplinary cooperation of surgeons, infectiologist, gastroenterologists, radiologists, microbiologists and pathologists.

Existing literature on this matter is scarce. Clinicians should consider AE in the differential diagnosis of focal liver lesions. The correct early diagnosis may exclude potential harm to the patient.

Conflicts of interest

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Funding

This work was supported by the Czech Ministry of Defence, Project MO 1012.

Ethical Approval

This case report did not require ethical approval.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Author contribution

RP: manuscript writing, literature search, first author; JP: literature search, patient care; RM, PH: description of the histopathology findings; MR, VH: final approval, patient care.

Registration of Research Studies

This case report is not registered in any database.

Guarantor

Radek Pohnán.

Acknowledgments

None.

References

- 1.Nunnari G., Pinzone M.R. Hepatic echinococcosis: clinical and therapeutic aspects. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012;18(13):1448–1458. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i13.1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolarova L., Mateju J., Hrdy J. Human alveolar echinococcosis: Czech Republic, 2007–2014. Emerg. Infect Dis. 2015;21(12):2263–2265. doi: 10.3201/eid2112.150743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S. Orgill DP, and the SCARE group: the SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartos V. Alveolar echinociccosis in the liver. Cas. Lek. Ces. 1928;67:1063. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vuitton D.A., Demonmerot F., Knapp J. Clinical epidemiology of human AE in Europe. Vet. Parasitol. 2015;213(3–4):110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2015.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunetti E., Kern P., Vuitton D.A. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Tropica. 2010;114:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eckert J., Deplazes P. Biological: epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2004;17(1):107–135. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.107-135.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stojkovic M., Mickan C., Weber T.F. Pitfalls in diagnosis and treatment of alveolar echinococcosis: a sentinel case series. BMJ. Open Gastroenterol. 2015;2(1):e000036. doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2015-000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottstein B., Reichen J. Hydatid lung disease (echinococcosis/hydatidosis) Clin. Chest Med. 2002;23(2):397–408. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(02)00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma Z.L., Ma L.G., Ni Y. Cerebral alveolar echinococcosis: a report of two cases. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2012;114(6):717–720. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albayrak Y., Kargi A., Albayrak A. Liver alveolar echinococcosis metastasized to the breast. Breast Care (Basel) 2011;6(4):289–291. doi: 10.1159/000331314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hozáková-Lukáčová L., Kolářová L., Rožnovský L. Alveolární echinokokóza – nově se objevující onemocnění? Cas. Lek. Ces. 2009;148(3):132–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottstein B., Reichen J. Echinococcosis/Hydatidosis. In: Cook G.C., Zumla A.I., editors. Manson ´s Tropical Diseases. 22nd edition. Saunders, Elsevier; 2009. pp. 1549–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozkok A., Gul E., Okumus G. Disseminated alveolar echinococcosis mimicking a metastatic malignancy. Intern. Med. 2008;47(16):1495–1497. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhuang H., Pourdehnad M., Lambright E.S. Dual time point 18F-FDG PET imaging for differentiating malignant from inflammatory processes. J. Nucl. Med. 2001;42:1412–1417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caoduro C., Porot C., Vuitton D.A. The Role of delayed 18F-FDG PET imaging in the follow-up of patients with alveolar echinococcosis. J. Nucl. Med. 2013;54:358–363. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.109942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kincekova J., Dubinsky P., Jr., Dvoroznakova E. Diagnostika a vyskyt alveolarnej echinokokozy na Slovensku. Clin Microbiol. Rev. 2005;59:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan S.A., Davidson B.R., Goldin R.D. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: an update. Gut. 2012;61:1657–1669. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrero J.A., Ahn J., Rajender Reddy K. ACG clinical guideline: the diagnosis and management of focal liver lesions. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1328–1347. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kupka T., Bala P., Hozakova L. Neobvyklý případ cystického postižení jater- alveolární echinokokóza jater. Vnitr. Lek. 2015;61(6):527–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]