Abstract

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is critical for mammary ductal development and differentiation, but how mammary fibroblasts regulate ECM remodeling remains to be elucidated. Herein, we used a mouse genetic model to activate platelet derived growth factor receptor-alpha (PDGFRα) specifically in the stroma. Hyperactivation of PDGFRα in the mammary stroma severely hindered pubertal mammary ductal morphogenesis, but did not interrupt the lobuloalveolar differentiation program. Increased stromal PDGFRα signaling induced mammary fat pad fibrosis with a corresponding increase in interstitial hyaluronic acid (HA) and collagen deposition. Mammary fibroblasts with PDGFRα hyperactivation also decreased hydraulic permeability of a collagen substrate in an in vitro microfluidic device assay, which was mitigated by inhibition of either PDGFRα or HA. Fibrosis seen in this model significantly increased the overall stiffness of the mammary gland as measured by atomic force microscopy. Further, mammary tumor cells injected orthotopically in the fat pads of mice with stromal activation of PDGFRα grew larger tumors compared to controls. Taken together, our data establish that aberrant stromal PDGFRα signaling disrupts ECM homeostasis during mammary gland development, resulting in increased mammary stiffness and increased potential for tumor growth.

Abbreviations: ECM, extracellular matrix; HA, hyaluronic acid; AFM, atomic force microscopy; CAFs, cancer-associated fibroblasts; MMFs, mouse mammary fibroblasts; TFM, traction force microscopy; LSL, lox-STOP-lox; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the leading cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide despite earlier diagnoses and the development of targeted therapies for certain breast cancer subtypes [1]. One contributor to therapeutic resistance and tumor recurrence is the cellular and acellular heterogeneity of the breast stroma [2]. The tumor stroma, similar to the normal breast stroma, is composed of several cell types, namely endothelia, perivascular cells, adipose tissue, immune cells and fibroblasts. Upon formation of invasive carcinoma these cell compartments are believed to be activated and tuned to a more pro-tumor phenotype [3]. Fibroblasts have been shown to regulate tumor growth and dissemination in many cancers, and genetic modifications in fibroblasts were previously shown to accelerate tumorigenesis in several mouse models [4], [5], [6], [7]. Fibroblasts are cells of mesenchymal origin that alternate between quiescent, proliferative and synthetic states [8]. During wound healing and cancer-associated synthetic stages, fibroblasts synthesize several components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) [8], [9], [10]. The ECM has been shown to affect tumor growth in several malignancies, such as those of the pancreas, lung and breast [7], [11], [12], [13]. Further, ECM deposition is known to alter mechanical properties of tissue, which in turn also exacerbate tumor growth [14], [15]. Stiffness of tissue is an emerging risk factor in breast cancer [16]. While much is known about the biochemical and biomechanical roles of ECM in breast cancer progression and metastasis, the signaling factors regulating these aspects of the ECM in concert remain largely unknown.

One of the biomolecular factors that stimulate activation of quiescent fibroblasts thereby leading to ECM deposition is PDGFRα. PDGFRα is a receptor tyrosine kinase that functions during development in a paracrine fashion in response to ligand (PDGFAA) binding which, in turn, initiates receptor dimerization and recruitment of adaptor proteins [17]. This pathway is active during development, where it is critical for several processes such as craniofacial development, spermatogenesis, lung alveologenesis and villus morphogenesis among others [17]. Further, it is found to be up-regulated in expression and/or function in glioblastoma multiforme, chronic myelogenous leukemia, non-small cell lung cancer and gastro-intestinal stromal tumors [18], [19], [20], [21] and preclinical successes have been achieved by inhibiting PDGFRα in these cancers [22], [23]. While the breast stroma expresses PDGFRα [24], little has been done to elucidate its role in mammary development or tumorigenesis.

In this study, we report that constitutive activation of PDGFRα in the mammary stromal fibroblast compartment obstructed invasion and branching of the ductal epithelium during post-pubertal development, but did not interrupt the epithelial differentiation program. Furthermore, activation of PDGFRα led to interstitial fibrosis in the mammary gland with a concomitant increase in collagen deposition and collagen-1 fiber length and width. PDGFRα activated fibroblasts also expressed higher levels of Has1, which encodes hyaluronic acid synthase1, an enzyme that produces hyaluronic acid (HA), and mammary tissue isolated from stromal PDGFRα activated mice displayed higher HA levels. Functionally, we also found that PDGFRα activated fibroblasts significantly reduced hydraulic permeability in a novel in vitro assay, and that this reduction was rescued by addition of crenolanib as well as hyaluronidase, the HA-cleaving enzyme. Notably, mammary tissue stiffness measured via atomic force microscopy (AFM) was significantly increased upon PDGFRα hyperactivation compared to controls. Increased orthotopic tumor growth in the mammary fat pads of stromal PDGFRα activated mutant animals was also observed. Taken together, our results indicate that PDGFRα signaling regulates collagen and HA deposition from the fibroblast compartment, and thus, is a key node in the regulation of mammary stiffness.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Animal use was in compliance with federal and University Laboratory Animal Resources regulations under protocol 2007A0120-R3 (MCO) approved by the OSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Transgenic Mice

Fsp-cre mice were generated and confirmed to express Fsp specifically within the mammary stromal fibroblasts as described previously [7], [25]. Pdgfraki/+ mice [26] were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), crossed with Fsp-cre mice, and bred back at least 7 generations in to FVB/N background. Mice were euthanized and harvested as outlined under university's IACUC protocol. Primary mouse mammary fibroblasts (MMFs) were isolated as described [27].

Whole-Mount Analysis

Inguinal mammary glands were harvested as described [28]. Briefly, whole mounted mammary glands were fixed, stained with carmine alum, dehydrated and mounted. Terminal end buds were quantified by measuring the number of bulbous structures in carmine stained whole mounted mammary glands from mice taken at 3 and 4 weeks of age.

Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

For immunofluorescence (IF), paraffin-embedded tissue was dewaxed, and subjected to antigen retrieval by steaming samples in Target retrieval solution (pH 6.1) (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA) or EDTA Decloaker (pH 8.0) (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, USA) for at least 40 minutes before blocking with Protein Block (DAKO). The following primary antibodies were then used: CK8 (TROMA-1, 1:400, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA, USA), α-SMA (A2547, 1:400, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Loius, MO, USA), PDGFR-α (3174, 1:100, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), Ki67 (ab16667, 1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), ERα (sc543, 1:10,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) and CD31 (PECAM1- sc1506, 1:500, Santa Cruz). For IF, Secondary detection was performed using antibodies conjugated to AlexaFluor dyes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were mounted with Prolong® Gold Antifade mount with DAPI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Representative fluorescent images were taken on an Eclipse E800 microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, USA) using the MetaVue™ Research Imaging system (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

For immunohistochemistry, sections were stained using the Bond RX autostainer (Leica Biosystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Slides were baked at 65 °C for 15 minutes and the automated system performed dewaxing, rehydration, antigen retrieval, blocking, primary antibody incubation, post primary antibody incubation, detection (DAB), and counterstaining using Bond reagents (Leica). Samples were then removed from the machine, dehydrated through a series of ethanol and xylenes and mounted. All quantitative imaging was done using the VECTRA® Automated Quantitative Pathology Imaging system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell Culture

Primary mouse mammary fibroblasts (MMFs) were purified as described [7], [27]. Briefly, mammary tissue was minced and digested with an enzymatic solution [0.15% Collagenase, C0130 (Sigma, Saint Loius, MO, USA), 160 U/ml hyaluronidase (H#4001, Sigma), insulin (#I5500, Sigma), 1 μg/ml hydrocortisone (#H4001, Sigma) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (ThermoFischer Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)] in 5% CO2 overnight at 37 °C. Tissue was neutralized with 10%FBS-DMEM (ThermoFisher), centrifuged and resuspended in 10%FBS-DMEM. Gravity separation was then utilized to separate out heavier epithelial organoids from the fibroblast fraction. After 24 hours, culture media was replaced with fresh 10%FBS-DMEM. For crenolanib experiments, crenolanib (Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA) was added to culture media at a concentration of 1 μM for 24 hours.

Tumor Models

To study primary tumor growth, an orthotopic injection model for breast cancer was employed. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and injected with 200,000 Met1 cells [29] in the inguinal mammary glands. Tumors were allowed to grow until one of the mice reached early removal criteria set by our IACUC. All mice were sacrificed at this time and ex vivo tumor measurements were made. Tumors were collected in formalin, paraffin embedded and sectioned for further analyses.

Analyses of Mammary Fat Fibrosis

Consecutive FFPE thin mammary gland sections were stained with H&E and trichrome and assessed by a veterinary pathologist (M.C.C.) for regions of fibrosis. Percent collagen positive area was quantified in ImageJ [30] by thresholding the color image and using “Analyze Particles” as previously described [6]. Similar color thresholds were used to quantify Alcian blue pH 2.5 and sirius red staining (Abcam) to determine percent HA+ area and collagen+ area respectively. For HABP staining, deparaffinized sections were first incubated with biotinylated HABP (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and detected using Alexa-Fluor-594 conjugated streptavidin (Invitrogen). Percent area was calculated in ImageJ by separating the channels, thresholding the red channel and using “Analyze”.

To assess collagen fiber characteristics, 12 μm FFPE sections were stained with sirius red (Abcam) and second harmonic generation microscopy was performed using the Olympus MV10000 Multiphoton microscope and MaiTai sapphire laser at 950 nm. Backscatter signal for the tissue was obtained at 850 nm. Second harmonic images thus obtained were then used to quantify collagen width and length using CT-fire (LOCI, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA). Briefly, SHG images were processed with the CT-FIRE algorithm to extract individual collagen fiber features such as orientation, width, and length. CT-FIRE parameters were optimized for SHG collagen optimal fiber segmentation and were kept constant for all images.

Hydraulic Permeability Measurements Using Microfluidic Devices

Straight channel polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic devices (L: 5 mm, W: 500 μm, T: 1 mm) were fabricated using soft lithography techniques [31]. PDMS devices were irreversibly sealed to a glass slide with plasma oxidation and sterilized for 30 min with UV prior to use. Acidic rat tail type I collagen (CORNING) was neutralized with NaOH and prepared to 7 mg/mL following the manufacturer's protocol to create stock collagen solutions. Immediately after neutralization, final collagen solutions were prepared at 6 mg/mL by diluting with cell culture medium with fibroblasts (1800 cells/μL) and without fibroblasts for acellular conditions. Final collagen solutions were also incubated for 12 min at 4 °C prior to injection to improve fiber nucleation prior to polymerization [32]. In addition, microfluidic devices were coated with fibronectin (100 μg/mL) prior to injection to promote adhesion to the channel walls [33]. Collagen solutions were injected into the microdevices and polymerized at 37 °C for 10 min. Cell culture medium was then added to the device ports/surface and was replaced daily prior to measurements. For inhibition experiments, HAdase (0.5 mg/mL) as well as crenolanib (1 μM) were dissolved in cell culture medium and made fresh daily for media replacements. Hydraulic permeability measurements were then made after 72 hours by applying a height based (1.8–2.2 cm) hydrostatic pressure difference between channel ports, resulting in fluid flow through the semi-porous collagen matrix. Time lapse microscopy images were recorded every 15 seconds for a duration of 20–30 min using an epifluorescence Nikon TS-100F microscope equipped with a Q-Imaging QIClick camera. FIJI was used to track the movement of the dye and estimate the average flow velocity. Darcy's law was then applied to calculate the hydraulic permeability (Eq. (1)) [34].

| (1) |

Where μ is the viscosity of the cell culture medium (approximated using water), v is the average fluid velocity, ∆L is the length of the channel, and ∆P is the pressure difference across the channel due to the difference in fluid height at the inlet and outlet ports and is given by Eq. (2).

| (2) |

Where ρ is the density of the cell culture medium (approximated using water), g is the acceleration due to gravity (9.81 m/s2), and h is the fluidic height difference between ports.

Atomic Force Microscopy of Unfixed Mammary Tissue

Mice were euthanized and a small piece of mammary tissue (5 mm x 5 mm) was excised from the nipple end of the #9 inguinal gland. This tissue was then attached to a coverslip using a biocompatible glue (epoxy resin) as described previously [35]. The tissue was then immediately immersed in sterile saline and atomic force microscopy performed. Briefly, stiffness measurements were performed using Asylum MFP-3D Bio AFM (Asylum Research, Goleta, CA, USA) mounted on an inverted fluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U). Samples were indented using silicon nitride cantilevers with a 10 μm polystyrene spherical tip and nominal spring constant of 0.01 N/m. Force maps at 5–10 regions of 20μmx20μm were collected and approximately 250–300 force-displacement curves were analyzed per sample for each matched pair (wild type and mutant) experiment. Force curves were analyzed using the Oliver-Pharr model to compute the tissue Young's modulus.

Traction Force Microscopy

Traction force microscopy was used to quantify the contractile forces generated by MMFs as described in [36]. Briefly, polyacrylamide (PA) gels with a Young's modulus of 5.9 kPa and embedded with 0.5 μm diameter red fluorescent carboxylate-modified beads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were prepared on 25 mm glass coverslips. These gels were coated with bovine collagen type I using heterobifunctional crosslinker sulfo-SANPAH. MMFs were sparsely seeded on the gels and cultured for 24 hours before imaging. Inverted fluorescent microscope (Olympus IX81, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to obtain phase contrast images of the single cell boundaries as well as the fluorescent images of the underlying beads before and after the cell detachment using trypsin. The bead displacement between the images with and without cells was computed using correlation-based particle image velocimetry (MATLAB, MathWorks, Natick, MA). These displacement data along with the cell boundaries were then used to compute the individual cell tractions using finite element model in Comsol (COMSOL Multiphysics, Burlington, MA) as described previously [37].

Quantitative Real-Time PCR and Immunoblots

Total RNA was obtained using TRIzol (Invitrogen), treated with DNAse I (ThermoFischer), and cDNA produced using Maxima Enzyme Mix (ThermoFisher). qRT-PCR was performed using Universal Probe Library system (Roche, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sample quality was verified by comparing Ct values for mouse ribosomal gene Rpl4. The following primer set-probe combinations were used: Col1a1, F-5’ccgctggtcaagatggtc-3′, R-5’ctccagcctttccaggttct-3′ (Probe#1); Loxl1, F-5’ctgccagtggatcgacataa-3′, R-5’acgtgcaccttgaggatgtag-3′ (Probe#64); Mmp3, F-5’tgcagctctactttgttctttga-3′, R-5’agagatttgcgccaaaagtg-3′ (Probe#7); Has1, F-5’caagacggagaagagagaatcc-3′, R-5’ctgagggctttggcatgt-3′ (Probe#76); Has2, F-5’cacacacacaccttagctcctc-3′, R-5’acccccattgaatgtctttg-3′ (Probe#3); Has3, F-5’gcactctgggtagtggtgct-3′, R-5’tcaagagagggacttaggtttca-3′ (Probe#3); Fap, F-5’gctacaaagccaagtactatgcac-3′, R-5’catggagggtggaaatgg-3′ (Probe #81); Rpl4, F-5’gatgagctgtatggcacttgg-3′, R-5’cttgtgcatgggcaggtta-3′ (Probe#38).

For immunoblotting, fibroblasts were lysed on ice (Cell signaling lysis buffer 9803), and protein levels quantified (DC Protein Assay, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Protein lysate was resolved using SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membrane (EMD Millipore). 5% milk-1XTBST was used to block and as a diluent for both primary (PDGFRα-3174, Cell Signaling; pPLCγ1-S1248–8713, Cell Signaling; pERK-4376, Cell Signaling, ERK-4695; GAPDH-25778, Santa Cruz) and secondary antibodies (HRP-conjugated; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Blot was probed with ECL detection kit (ThermoFischer) and developed using X-ray film.

Statistical Methods

Sample size was not pre-determined statistically. All conclusions were determined by analyzing distinct genetic groups in a blinded fashion. Within each genetic group, mice were randomly utilized. For data of sample sizes >five, normal distribution was determined by Kolmogorov–Smirnov Goodness-of-Fit. Sample variance was determined by F-test. Statistical comparison between two groups of normally distributed data was done by homoscedastic or heteroscedastic Student's t-test as appropriate. All analyses using Student's t-test were two-tailed. For tumor data, statistical comparisons were done by Mann–Whitney. For AFM and TFM, non-parametric one way ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test on ranks) was run followed by pairwise comparisons using Dunn's method. Hydraulic permeability measurements were recorded from 5–11 separate microdevices per condition from 2–3 experiments. Data for each condition was pooled together and analyzed for statistical significance using JMP (SAS Institute). Statistical testing was performed using ANOVA with Tukey–Cramer post testing to identify statistical significance compared to control MMFs, setting P < .05 as the threshold.

Results

Loss of PTEN in Mammary Fibroblasts Up-Regulates PDGFRα

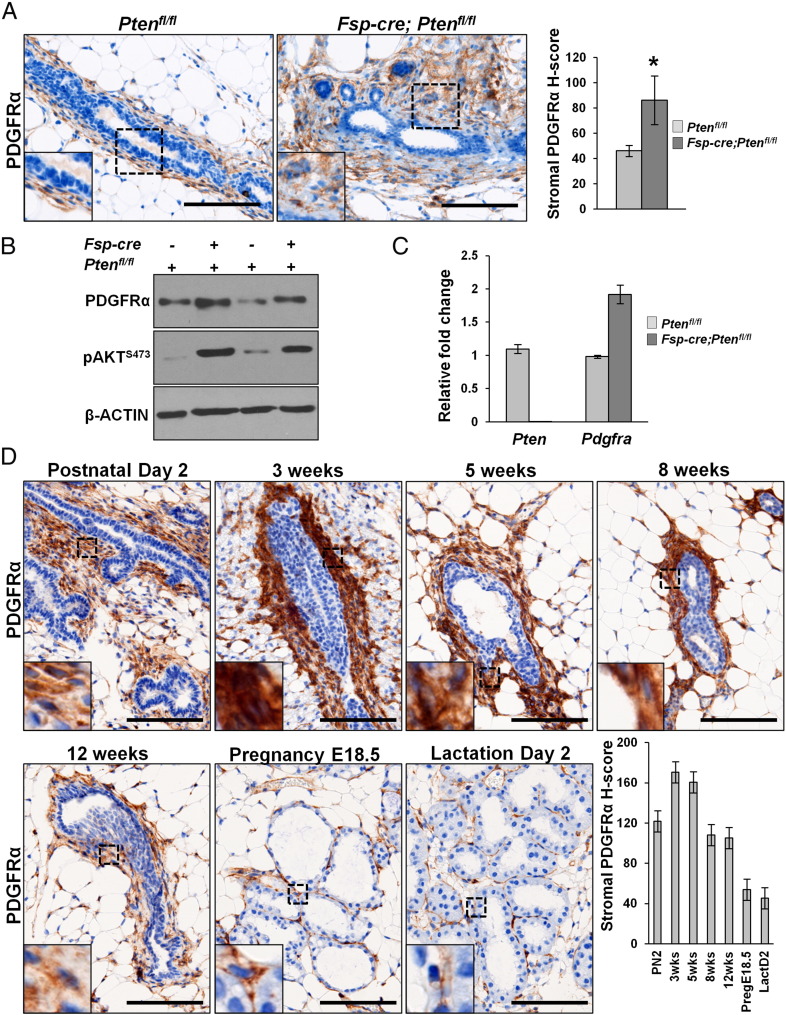

We previously demonstrated that loss of stromal Pten using the fibroblast-specific Fsp-cre increased tumorigenesis of MMTV driven Erbb2 mammary tumors in mice [7]. Further, it was shown that this loss of stromal PTEN led to increased ECM deposition through a microRNA-320-Ets2 dependent pathway [11]. PDGFRα is a well-known pharmaceutically targetable factor whose activation also leads to ECM deposition in several organs [17]. We thus analyzed mammary tissue sections from either Ptenfl/fl or Fsp-cre;Ptenfl/fl mice to assess stromal PDGFRα levels in these mice. We found significantly increased PDGFRα expression by immunohistochemistry in stromal PTEN-null mammary glands (Figure 1A). Further, mammary fibroblasts isolated from Fsp-cre;Ptenfl/fl mice also displayed increased PDGFRα protein (Figure 1B) and mRNA (Figure 1C) as evidenced by western blot and quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR), respectively. Combined, these data suggest increased stromal PDGFRα could at least in part be contributing to the increased ECM observed in the Fsp-cre;Ptenfl/fl mice.

Figure 1.

PDGFRα is up-regulated upon stromal PTEN deletion and is expressed in the stroma throughout normal mouse mammary gland development. A, Representative images and quantification for PDGFRα staining on mammary gland sections from Ptenfl/fl and Fsp-cre;Ptenfl/fl mice (≥3 images per mouse, 3 mice per genotype; Scale bars – 100 μm; Bars represent the mean ± S.E.M, *P < .05). B, Western blots for PDGFRα and phospho-AKT expression in MMFs isolated from Ptenfl/fl and Fsp-cre;Ptenfl/fl mice. C, qRT-PCR for Pten and Pdgfra mRNA in MMFs derived from Ptenfl/fl and Fsp-cre;Ptenfl/fl mice (bars represent the mean ± S.E.M. relative to Rpl4) D, Representative images and quantification for PDGFRα staining on FFPE mammary sections harvested from virgin wild-type FVB/N mice at postnatal day 2 (PN2), 3 week, 5 week, 8 week, and 12 week of age. Glands were also harvested at pregnancy (embryonic day 18.5) and lactation (day 2) (≥5 images taken per mammary gland section, 3 mice per time point; Scale bars – 100 μm; Bars represent the mean ± S.E.M).

PDGFRα is Expressed in the Stroma of the Developing Mouse Mammary Gland

PDGFRα is chiefly expressed in mesenchymal cell compartments throughout murine development [17]. Specifically in the mammary gland, expression of the predominant ligand, Pdgfa, is seen in the developing epidermal mammary bud as early as E14.5 with expression of the receptor seen in surrounding mesenchyme at this stage of development [38]. In order to fully characterize PDGFRα expression in the postnatal developing mammary gland, we harvested tissues in virgin wild-type FVB/N mice at varying time points: perinatal (postnatal day 2), early puberty (3 weeks), mid puberty (5 weeks), late puberty (8 weeks) and post puberty (12 weeks). We also evaluated adult glands during pregnancy (embryonic day 18.5) and lactation (day 2) (Figure 1D). We found that PDGFRα expression was highest at 3 weeks, and gradually declined with the age of the mouse reaching its minimum during pregnancy and lactation (Figure 1D).

Activation of PDGFRα in Stromal Fibroblasts Abrogates Mammary Ductal Development but Does not Interrupt the Epithelial Differentiation Program

The role of PDGFAA-PDGFRα signaling in mouse embryonic development has been well described [17], however the role of this signaling pathway in the developing mammary gland remains understudied. To assess the role of PDGFRα signaling in this tissue, we utilized a mouse model of fibroblast-specific PDGFRα activation. These mice were generated by crossing the fibroblast-specific Fsp-cre allele developed by our group [7] with the commercially available LSL-D842V-PDGFRα heterozygous knock-in mouse model, hereafter referred to as Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ (Supplemental Figure 1A). The Pdgfraki/+ mice harbor a mutation in the activation loop of PDGFRα tyrosine kinase domain that was generated by knocking in the D842V-Pdgfra cDNA, flanked by a LOX-STOP-LOX cassette, into the endogenous Pdgfra locus [26]. Mice homozygous for the knock-in mutation (Pdgfraki/ki) are effectively Pdgfra−/− mice without a cre, rendering them embryonic lethal [26]. All mutant mice used in this study were heterozygous for the knock-in allele.

To confirm activation of stromal PDGFRα in the mammary glands of mutant mice, we isolated and purified mouse mammary fibroblasts (MMFs). Genomic DNA from the purified MMFs was then PCR amplified using primers to detect removal of the LOX-STOP-LOX cassette as described previously [26]. We found that MMFs from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice had efficient deletion using these primers as evidenced by the 2 kb LOX-STOP-LOX removal band (Supplemental Figure 1B). Further, western blot analysis revealed activation of phospholipase C-γ (PLCγ) exclusively in the MMFs from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice (Supplemental Figure 1C). This is a surrogate marker for PDGFRα activation since PLCγ docks on the intracellular kinase domain of PDGFRα where it is phosphorylated by PDGFRα [17], [26].

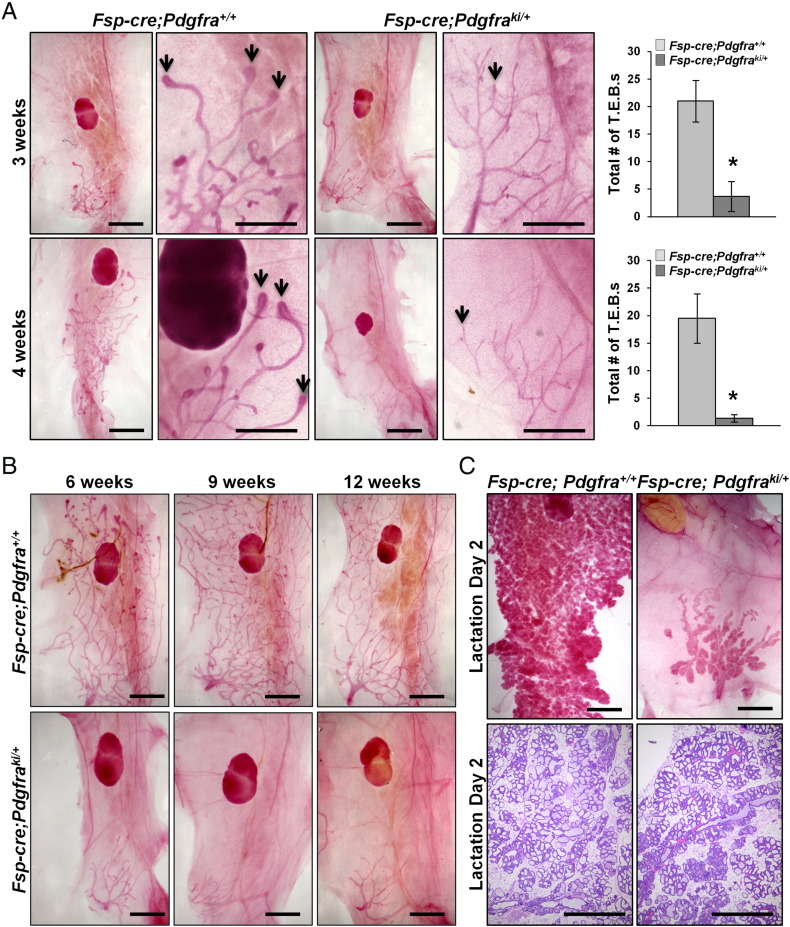

To evaluate the effect stromal PDGFRα activation has on mammary ductal invasion, we examined morphological differences by whole mount analysis throughout development. At postnatal day 2 (PN2), mammary glands from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice appeared morphologically and histologically normal (Supplemental Figure 2A). In contrast, at 3 weeks of age, there was a near complete absence of terminal end buds (TEBs) in glands from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice (Figure 2A–top). Under control conditions, the TEBs are highly proliferative, bulbous structures appearing at puberty that are responsible for moving the epithelium through the ECM, thereby causing ductal elongation [39]. Similar findings were observed at 4 weeks of age (Figure 2A–bottom). Importantly, even upon completion of puberty, the mammary glands from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice never underwent normal ductal elongation through the entire fat pad (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Stromal PDGFRα activation abrogates mammary ductal invasion but does not interrupt the differentiation program. A, (Left) Representative whole mounted, carmine stained mammary glands at 3 and 4 weeks of age from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ and Fsp-cre;Pdgfra+/+ mice. (Right) Quantification of total number of terminal end buds (T.E.B.s) shown on the right (mean ± S.E.M, *P < .05). B, Representative whole mounted, carmine stained mammary glands at 6, 9 and 12 weeks of age. C, Whole mounted, carmine stained mammary glands and hematoxylin stained sections of lactation day2 mammary glands from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ and littermate controls. 3 mice per genotype per time point for A, B and C; Scale bars 400 μm).

Given the dramatic defect in mammary ductal development, we then further assessed mammary ducts in Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice for histological alterations. Mammary glands were isolated from virgin females at 8 weeks of age and immunostained for: (1) estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), an essential regulator of hormone-induced ductal elongation [40], [41], (2) cytokeratin 8 (CK8), a luminal epithelial marker [42], and (3) alpha-smooth muscle actin (αSMA), a basal-myoepithelial marker [42]. Mammary glands from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice had normal levels of ERα in the ductal epithelium indicating that loss of ERα was not causative in the observed ductal phenotype (Supplemental Figure 2B). Further, localization and expression of CK8 and αSMA were indistinguishable between mammary glands from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ animals compared to controls (Supplemental Figure 2, C and D). These results further indicate that while activation of PDGFRα in the mammary stroma was capable of inhibiting ductal elongation, it did not affect the epithelial ductal architecture.

In order to test whether activation of PDGFRα in the mammary stroma affected the alveolar differentiation capacity of the mammary epithelium, adult Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ females were bred with wild-type males. We found that not only were Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ females able to get pregnant, they were also capable of lactating, albeit to a lesser degree than control littermates as the ductal tree was still severely impaired (Figure 2C). Litters born to Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice consistently died due to insufficient milk production by the dams (data not shown). Combined, these data indicate that while stromal PDGFRα signaling has an important role in ductal elongation, its activation does not interfere with ductal-alveolar differentiation.

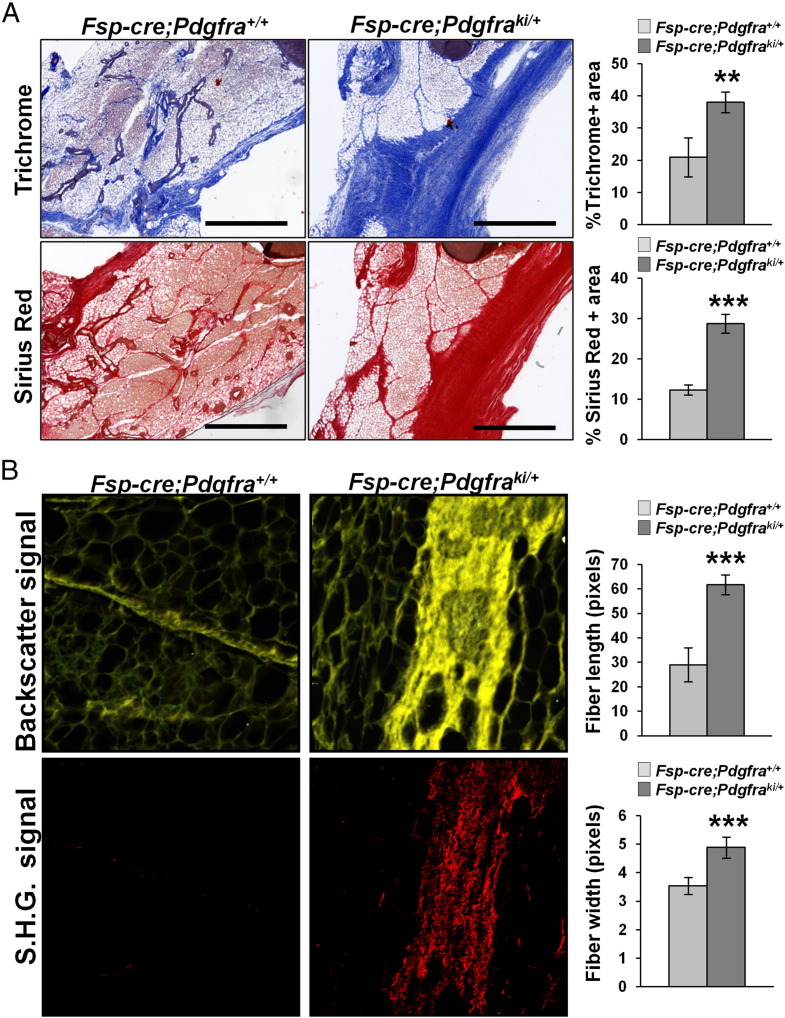

Stromal PDGFRα Activation Leads to Fibrosis in the Mammary Gland, Increased Expression of Has1 and Increased Deposition of Hyaluronic Acid Into the Mammary ECM

To determine the effect of PDGFRα activation on the stroma and ECM, we analyzed thin sections of the mammary gland from 4 week old female Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice and littermate controls (H&E in Supplemental Figure 3). Even at this early stage of mammary gland development, massive fibrosis was evident in Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice compared to controls, as revealed by quantitation of trichrome and sirius red staining of collagen (Figure 3A). Second harmonic generation microscopy of mammary gland sections from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ stained with sirius red demonstrated an increase in collagen-1 fiber length and width (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Stromal PDGFRα activation causes mammary fat pad fibrosis. A, Representative images and quantification of trichrome and sirius red stained Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ and Fsp-cre;Pdgfra+/+ mammary gland sections to detect collagen deposition (mean ± S.E.M., **P < .01, ***P < .001). B, Second harmonic imaging of FFPE mammary gland sections from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ and Fsp-cre;Pdgfra+/+ mice and quantification of collagen fiber length and width (mean ± S.E.M., ***P < .001) (3 mice per genotype, 1 mammary gland per mouse, 3 images per mammary gland; Scale bars – 400 μm).

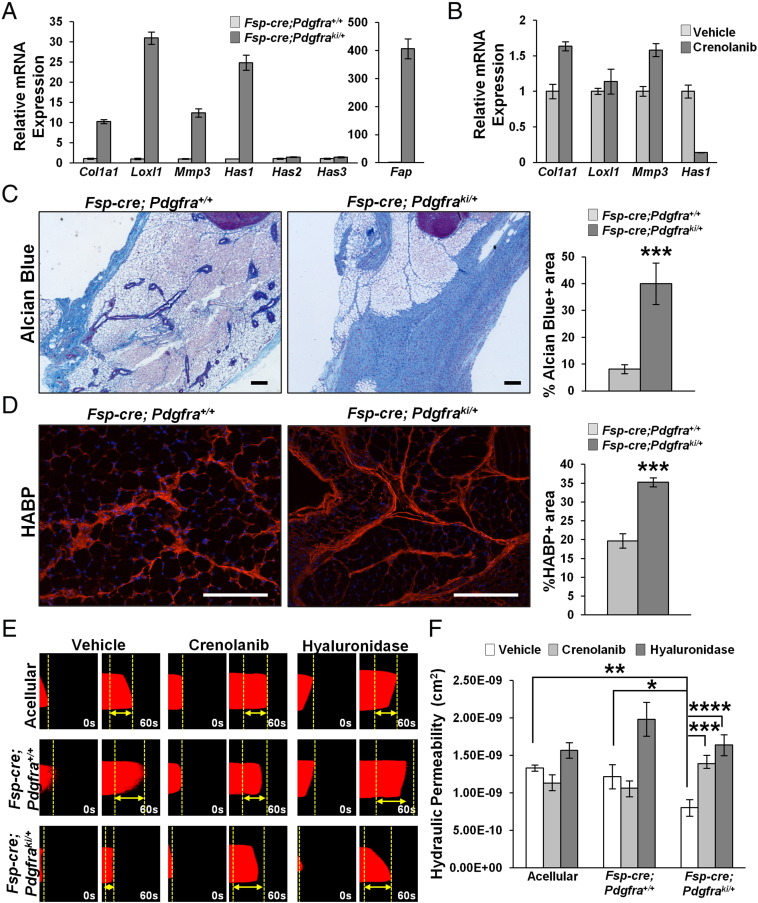

To gain insight into the molecular mechanisms behind the mammary fat fibrosis observed with stromal activation of PDGFRα, we performed gene expression analysis on purified MMFs and found a dramatic up-regulation in genes responsible for production, cross-linking and remodeling of collagen I, i.e. Col1a1, Loxl1 and Mmp3, respectively (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 4A represent two independent pairs of mice). These data are consistent with the increased collagen deposition and fiber size demonstrated in Figure 3. Further, it is well-known that HA is present in the normal mammary gland [43] and its expression is increased upon injury and fibrosis [44]. We thus determined if any of the HA-synthase-encoding genes were aberrantly expressed in MMFs with PDGFRα activation, and found that while there was a significant increase in Has1 expression, Has2 and Has3 remained unaltered (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 4A represent two independent mice). Further, we saw a striking increase in Fap which is an activated fibroblast marker (Figure 4A and Supplementary 4A) [8]. Interestingly, inhibition of PDGFRα-D842V with the small molecule RTK inhibitor, crenolanib [22] significantly diminished Has1 expression in the PDGFRα activated MMFs, but did not affect Col1a1, Loxl1 and Mmp3 (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure 4B represent two independent mice). These data suggest that Has1 is a direct target of PDGFRα signaling in the mammary stroma rather than as an indirect effect of fibroblast activation due to hyperactive PDGFRα.

Figure 4.

Stromal PDGFRα activation causes increased HA deposition and decreased hydraulic permeability. A, qRT-PCR for Col1a1, Loxl1, Mmp3, Has1, Has2, Has3 and Fap mRNA in MMFs derived from Fsp-cre;Pdgfra+/+ and Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice (bars represent the mean ± S.E.M. relative to Rpl4). B, qRT-PCR for Col1a1, Loxl1, Mmp3 and Has1 mRNA in MMFs derived from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice treated with 1 μM crenolanib (bars represent the mean ± S.E.M. relative to Rpl4). Representative images and quantification for Alcian blue (C) and hyaluronic acid binding protein (HABP) staining (D) on mammary tissue (≥3 images per mouse, 3 mice per genotype; Scale bars – 100 μm; Bars represent the mean ± S.E.M, ***P < .001) E, Hydraulic permeability measurements for fibroblasts isolated from Fsp-cre;Pdgfra+/+ and Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice and treated with crenolanib or hyaluronidase (mean ± S.E.M).

To confirm the functional significance of increased Has1 as a result of PDGFRα activation, we stained tissue sections from 4 week old Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ and controls with Alcian blue, which stains acidic proteoglycans [45]. Indeed, Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mammary glands exhibit significantly increased Alcian blue-positive areas compared to control tissue establishing increased HA content in the Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ fat pads (Figure 4C). Increased HA was further evaluated by staining tissue sections with HA-binding protein (HABP), wherein we also observed increased HABP-stained areas in Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice versus controls (Figure 4D).

PDGFRα Activation Decreases Hydraulic Permeability in an In Vitro Assay

Hydraulic permeability, or the permissiveness to fluid flow through tissue, is determined primarily by the collagen and HA composition of the tissue ECM [46]. Decreased hydraulic permeability is characteristic of tumors with high stromal content, such as the pancreas, where it inhibits drug delivery, compresses vasculature and creates hypoxic conditions, leading to a more aggressive tumor [47]. To assess the effect of constitutive PDGFRα activation on hydraulic permeability, we utilized a single channel microfluidic assay that contains fibroblasts seeded within 3-D collagen I gels such that the only pathway for unidirectional flow is through this semi-porous matrix (Supplemental Figure 4). Fibroblasts were allowed to remodel the matrix for 3 days. Subsequently, tetramethylrhodamine-bovine serum albumin (TRITC-BSA) tracer dye dissolved in culture media was flowed through the microchannel, and time-lapse microscopy was used to track the position of the dye (Figure 4E). Measurements of the dye velocity revealed that MMFs from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice significantly lowered the hydraulic permeability by 34% significantly compared to control MMFs, and 40% compared to acellular controls (Figure 4, E and F). Furthermore, the decreased permeability of the MMFs with hyperactivated PDGFRα was significantly rescued by treatment with crenolanib (73% increase) and hyaluronidase (104% increase) respectively compared to untreated mutant MMFs (Figure 4F). In comparison, treatment of the control MMFs with crenolanib and hyaluronidase resulted in a small decrease (12%) and rescue (63%) in hydraulic permeability respectively compared to untreated control MMFs. These results suggest that the decreased permeability measured in hyperactivated PDGFRα MMFs was directly due to PDGFRα activation and subsequent HA deposition to the ECM respectively. While there was also a rescue of the hydraulic permeability of the control fibroblasts treated with hyaluronidase, this result may be attributed to efficient enzymatic ablation by hyaluronidase to the comparatively lower quantities of HA produced by the control fibroblasts (Figure 4, A, C and D).

Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ Mice Display Significantly Increased Mammary Stiffness

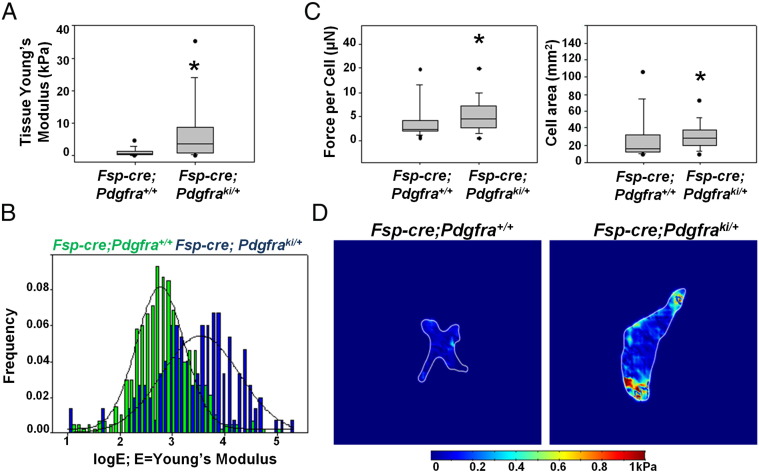

We hypothesized that the interstitial fibrosis with increased collagen and HA deposition in combination with the reduced hydraulic permeability seen in our model was altering the stiffness of the mammary gland from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice. To address this, mice were harvested at 4 weeks of age and the inguinal mammary gland at the nipple end was dissected. This unfixed tissue was then subjected to atomic force microscopy to measure tissue stiffness. As early as 4 weeks of age, mammary glands from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice were significantly stiffer than control (Figure 5, A and Band Supplemental Figure 5 represent three independent pairs of mice). Furthermore, traction force microscopy, which measures the force exerted by fibroblasts on the ECM, indicates that MMFs from stromal PDGFRα activated mice have an increased traction force per cell compared to controls and also exhibit an increased cell spread area (Figure 5, C and D). Increased traction force leads to a more compact ECM, consistent with the ex vivo increase in mammary tissue stiffness.

Figure 5.

Stromal PDGFRα activation increases mammary tissue stiffness. A, Atomic force measurements of unfixed whole mammary tissue (Young's modulus of elasticity) from Fsp-cre;Pdgfra+/+ and Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice (*P < .05). B, Histogram showing distribution of Young's modulus for individual data points for experiment shown in A. C, Quantification of force per cell and cell area as determined by traction force microscopy (*P < .05). D, Representative heat map showing force distribution in one cell from each genotype.

Stromal PDGFRα Activation Accelerates Orthotopic Tumor Growth

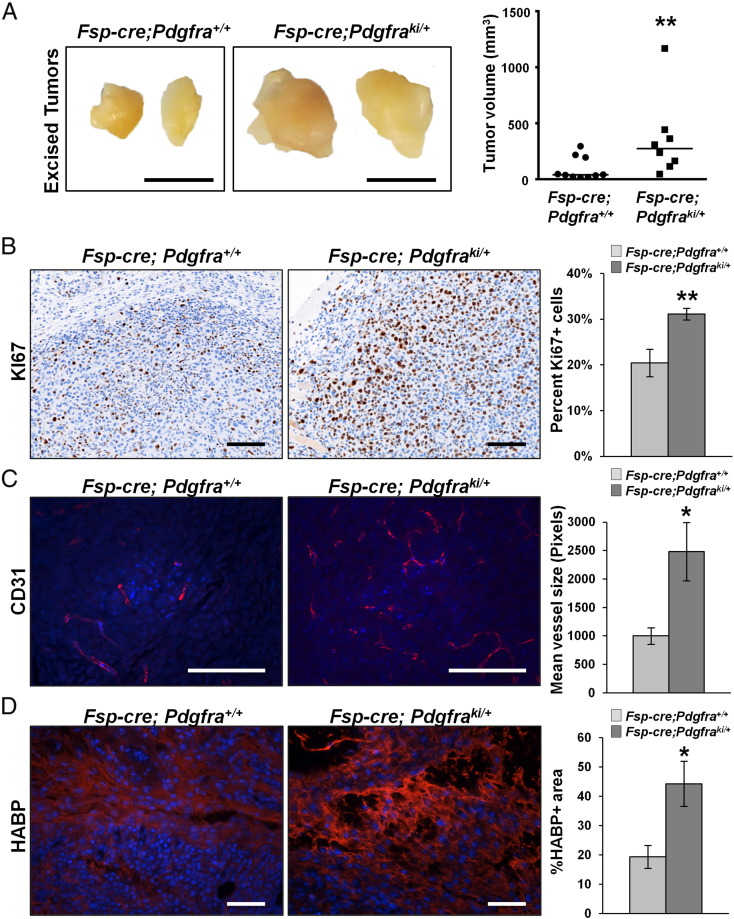

Knowing that increased mammary stiffness can lead to increased tumor growth and metastatic spread [48], [49], [50], [51], we further evaluated orthotopic tumor growth in Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+mice. MMTV-PyMT derived Met1 mammary tumor cells [29], which express high levels of the PDGFRα ligand, Pdgfa (data not shown), were injected into the fat pads of Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ and control females. Importantly, tumors in Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice grew significantly larger compared to controls (Figure 6A). Further, the tumors in the Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice were more proliferative than controls as indicated by Ki67 staining (Figure 6B). They also displayed increased angiogenesis as measured by increased CD31+ vessel size (Figure 6C). Importantly, tumors from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ had significantly greater HA deposition (HABP staining) (Figure 6D). These findings parallel our observations in the virgin, non-tumor bearing Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mammary glands, and suggest that PDGFRα activated fibroblasts produce greater amounts of HA that result in a pro-tumorigenic stromal microenvironment.

Figure 6.

Stromal PDGFRα activation increases growth of Met1 cells in the mammary fat pad. A, Representative images and tumor volume quantification of Met1 mammary tumors arising in orthotopically injected Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ and littermate controls (Scale bar – 5 mm). Representative images and quantification of B. percent KI67 positive nuclei, C, CD31 mean vessel size, and D, HABP signal intensity within Met1 tumor sections from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice and controls (Control = 10 tumors, Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ = 8 tumors; ≥5 images per tumor; Scale bars – 100 μm).

Discussion

Our work demonstrates that hyperactivation of stromal PDGFRα impedes mammary ductal development without interfering with pregnancy induced lobulo-alveologenesis. Postnatal mammary gland development requires a constant flux in ECM remodeling and composition [52], [53], [54]. ECM turnover itself is dictated by the action of several enzymes such as lysyl oxidases and matrix metalloproteases acting in concert [55], [56], [57] with cell-matrix interactions considered crucial for proper mammary gland development [56]. It has also been posited that ECM-mediated mechanical forces guide ductal morphogenesis in the mammary gland [54]. Thus, a viable mechanism to explain loss of mammary ductal invasion in the Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice might be the mechanical barrier imposed by increased mammary gland stiffness and decreased hydraulic permeability that result from stromal PDGFRα hyperactivation. While evidence of ligand expression in the epithelium during murine pregnancy is lacking, a previous study of rhesus macaques revealed that PDGFRA gene expression reached a nadir during pregnancy and lactation [58]. Taken together with our observation of the maintenance of lobulo-alveologenesis in lactating Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice, this suggests that lobulo-alveolar differentiation occurs independently of PDGFRα-PDGFA paracrine signaling pathway.

Fibrosis is observed in various organ systems such as respiratory, renal and cardiovascular [59], [60], [61]. Furthermore, fibrosis, also termed desmoplastic reaction (i.e. the incorrect activation of the wound healing response), is characteristic of several solid tumors including pancreas and breast [8]. Our finding that PDGFRα activation in mammary fibroblasts induces such desmoplasia in absence of an oncogenic hit provides evidence that quiescent mammary fibroblasts expressing constitutive PDGFRα have the capacity to become fibrosis-associated fibroblasts, whose phenotype more closely resembles cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [8], [62]. Gene expression profiling of MMFs isolated from the Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice revealed that CAF-associated collagen remodeling genes such as Mmp3 [63] and Loxl1 [11], [64] are significantly up-regulated, suggesting a priming of the tumor microenvironment for oncogenesis. While spontaneous tumors do not arise in these mice, the increased growth of the Met1 tumor cells in the fat pads of Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ provides evidence for a tumor-promoting microenvironment. Furthermore, our data with PDGFR-inhibition and the dramatic up-regulation of the activated fibroblast marker Fap in MMFs from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice support that Has1 is a direct target of PDGFRα signaling while the up-regulation of aforementioned collagen remodeling genes (Col1a1, Loxl1, Mmp3) is likely an indirect result of sustained fibroblast activation.

In the past decade, the view of fibroblasts and the ECM, particularly a fibrotic ECM, has turned from being a bystander of tumor growth, to both a biochemical promoter and a biomechanical partner of tumorigenesis. Several comprehensive studies have shown that ECM deposition and subsequent alterations in the mechanical properties of cells and tissues can alter tumor cell behavior, leading to more proliferative and invasive tumors [12], [49], [50], [51], [65]. Further, total stress (force/area) in tissue is a result of both solid and fluid stress [47]. Here, we not only demonstrate that the stiffness of the mammary tissue, a contributor to externally applied solid stress, is increased in mammary glands from Fsp-cre;Pdgfraki/+ mice, but also our data with HA deposition and hydraulic permeability imply an increase in fluid stress via increased interstitial fluid pressure (IFP). Our study suggests that this increase in total stress of the tissue is likely causing the increased tumor growth observed. The main question that remains is whether this increased tumor growth is a direct result of the biophysical changes in the tissue, a result of the biochemical changes in the hyperactivated-PDGFR fibroblast secretome, or perhaps some combination of both. Future experiments, beyond the scope for this current work, will be required to examine this question.

In conclusion, our data proposes a novel biochemical-biomechanical role for activated fibroblasts in both the normal development of the mammary gland as well as tumorigenesis within this tissue. PDGFRα activation invoked mammary fat pad fibrosis and decreased hydraulic permeability, which likely led to a dramatic increase in mammary stiffness and a pro-tumorigenic stromal microenvironment. These findings have translational relevance in that PDGFRα is a promising therapeutic target in the mammary stroma, and drugs targeting this receptor (e.g., crenolanib) are already FDA approved. Combined, these data provide evidence of the first genetic in vivo model of increased stiffness that can be utilized to study the mechanical effects on tumor growth.

Conflicts of Interest

none.

Author Contributions

All authors assisted with data interpretation, manuscript review and writing the manuscript. AMH, GMS and MCO conceived and designed the research. AMH bred, genotyped and harvested all G.E.M. mice, did whole mount imaging and quantification, immunofluorescent staining and imaging, cell culture, western blots and real time PCRs for PDGFRα activated MMFs, immunohistochemistry imaging and quantification, fibrosis staining and quantification, second harmonic generation microscopy and tumor cell injections and analysis. GMS and AMH harvested FVB/N female mice and stromal PTEN knockout mice. GMS performed western blots and real time for Pten null MMFs. VCS performed AFM and TFM. AA and JJC performed hydraulic permeability assays. MCC provided pathology expertise. RDK performed immunohistochemistry for PDGFRα and KI67. QV and KT assisted with genotyping. STS, AC, GL and LDY provided cancer expertise in patients and mouse models. JWS and SNG provided biomechanics expertise. AMH and GMS prepared figures. AMH wrote the manuscript. MCO supervised the research.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Jason Bice and Daphne Bryant in the Solid Tumor Biology histology core at OSU-CCC for assisting with paraffin embedding, sectioning, H&E and trichrome staining of tissue samples. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Sara Cole in OSU-CMIF for her help with second harmonic generation and Sarah Bushman for assistance with hydraulic permeability assays. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (PO1CA097189) to MCO, Department of Defense (W81XWH-14-1-0040) to GMS, National Science Foundation (1134201) to SNG and Pelotonia Fellowship Program to G.M.S. and K.T.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neo.2017.04.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global Cancer Incidence and Mortality Rates and Trends--An Update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;25:16–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertos NR, Park M. Breast cancer — one term, many entities? J Clin Investig. 2011;121:3789–3796. doi: 10.1172/JCI57100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalluri R, Zeisberg M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrc1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhowmick NA, Chytil A, Plieth D, Gorska AE, Dumont N, Shappell S, Washington MK, Neilson EG, Moses HL. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science. 2004;303:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng N, Bhowmick NA, Chytil A, Gorksa AE, Brown KA, Muraoka R, Arteaga CL, Neilson EG, Hayward SW, Moses HL. Loss of TGF-β type II receptor in fibroblasts promotes mammary carcinoma growth and invasion through upregulation of TGF-α-, MSP- and HGF-mediated signaling networks. Oncogene. 2005;24:5053–5068. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu X, Pitarresi JR, Cuitiño MC, Kladney RD, Woelke SA, Sizemore GM, Nayak SG, Egriboz O, Schweickert PG, Yu L. Genetic ablation of Smoothened in pancreatic fibroblasts increases acinar–ductal metaplasia. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1943–1955. doi: 10.1101/gad.283499.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trimboli AJ, Cantemir-Stone CZ, Li F, Wallace JA, Merchant A, Creasap N, Thompson JC, Caserta E, Wang H, Chong J-L. Pten in stromal fibroblasts suppresses mammary epithelial tumours. Nature. 2009;461:1084–1091. doi: 10.1038/nature08486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:582–598. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simian M. The interplay of matrix metalloproteinases, morphogens and growth factors is necessary for branching of mammary epithelial cells. Development. 2001;128:3117–3131. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–363. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bronisz A, Godlewski J, Wallace JA, Merchant AS, Nowicki MO, Mathsyaraja H, Srinivasan R, Trimboli AJ, Martin CK, Li F. Reprogramming of the tumour microenvironment by stromal PTEN-regulated miR-320. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;14:159–167. doi: 10.1038/ncb2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laklai H, Miroshnikova YA, Pickup MW, Collisson EA, Kim GE, Barrett AS, Hill RC, Lakins JN, Schlaepfer DD, Mouw JK. Genotype tunes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma tissue tension to induce matricellular fibrosis and tumor progression. Nat Med. 2016;22:497–505. doi: 10.1038/nm.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis will increase the risk of lung cancer. Chin Med J (Engl) 2014;127:3142–3149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang TT, Thakar D, Weaver VM. Force-dependent breaching of the basement membrane. Matrix Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickup MW, Mouw JK, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix modulates the hallmarks of cancer. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1243–1253. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyd NF, Li Q, Melnichouk O, Huszti E, Martin LJ, Gunasekara A, Mawdsley G, Yaffe MJ, Minkin S. Evidence That Breast Tissue Stiffness Is Associated with Risk of Breast Cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1276–1312. doi: 10.1101/gad.1653708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Joensuu H, McGreevey LS, Chen CJ, Van den Abbeele AD, Druker BJ. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4342–4349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermanson M, Funa K, Koopmann J, Maintz D, Waha A, Westermark B, Heldin CH, Wiestler OD, Louis DN, von Deimling A. Association of loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 17p with high platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor expression in human malignant gliomas. Cancer Res. 1996;56:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lokker NA, Sullivan CM, Hollenbach SJ, Israel MA, Giese NA. Platelet-derived Growth Factor (PDGF) Autocrine Signaling Regulates Survival and Mitogenic Pathways in Glioblastoma Cells: Evidence That the Novel PDGF-C and PDGF-D Ligands May Play a Role in the Development of Brain Tumors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3729–3735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rikova K, Guo A, Zeng Q, Possemato A, Yu J, Haack H, Nardone J, Lee K, Reeves C, Li Y. Global Survey of Phosphotyrosine Signaling Identifies Oncogenic Kinases in Lung Cancer. Cell. 2007;131:1190–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinrich MC, Griffith D, McKinley A, Patterson J, Presnell A, Ramachandran A, Debiec-Rychter M. Crenolanib Inhibits the Drug-Resistant PDGFRA D842V Mutation Associated with Imatinib-Resistant Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4375–4384. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang P. Crenolanib, a PDGFR inhibitor, suppresses lung cancer cell proliferation and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Oncotargets Ther. 2014;7:1761–1768. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S68773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Travers MT. Growth factor expression in normal, benign, and malignant breast tissue. Br Med J. 1988;296 doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6637.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trimboli AJ, Fukino K, de Bruin A, Wei G, Shen L, Tanner SM, Creasap N, Rosol TJ, Robinson ML, Eng C. Direct Evidence for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:937–945. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olson LE, Soriano P. Increased PDGFRα Activation Disrupts Connective Tissue Development and Drives Systemic Fibrosis. Dev Cell. 2009;16:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soule HD, McGrath CM. A simplified method for passage and long-term growth of human mammary epithelial cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1986;22:6–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02623435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sizemore GM, Balakrishnan S, Hammer AM, Thies KA, Trimboli AJ, Wallace JA, Sizemore ST, Kladney RD, Woelke SA, Yu L. Stromal PTEN inhibits the expansion of mammary epithelial stem cells through Jagged-1. Oncogene. 2016;36:2297–2308. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borowsky AD, Namba R, Young LJT, Hunter KW, Hodgson JG, Tepper CG, McGoldrick ET, Muller WJ, Cardiff RD, Gregg JP. Syngeneic mouse mammary carcinoma cell lines: Two closely related cell lines with divergent metastatic behavior. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2005;22:47–59. doi: 10.1007/s10585-005-2908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abràmoff MD, Magalhães PJ, Ram SJ. Image processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qin D, Xia Y, Whitesides GM. Soft lithography for micro- and nanoscale patterning. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:491–502. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sung KE, Su G, Pehlke C, Trier SM, Eliceiri KW, Keely PJ, Friedl A, Beebe DJ. Control of 3-dimensional collagen matrix polymerization for reproducible human mammary fibroblast cell culture in microfluidic devices. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4833–4841. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bischel LL, Beebe DJ, Sung KE. Microfluidic model of ductal carcinoma in situ with 3D, organotypic structure. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:12. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1007-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiig H, Swartz MA. Interstitial fluid and lymph formation and transport: physiological regulation and roles in inflammation and cancer. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:1005–1060. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plodinec M, Loparic M, Monnier CA, Obermann EC, Zanetti-Dallenbach R, Oertle P, Hyotyla JT, Aebi U, Bentires-Alj M, Lim RYH. The nanomechanical signature of breast cancer. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7:757–765. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volakis LI, Li R, Ackerman WEt, Mihai C, Bechel M, Summerfield TL, Ahn CS, Powell HM, Zielinski R, Rosol TJ. Loss of myoferlin redirects breast cancer cell motility towards collective migration. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zielinski R, Mihai C, Kniss D, Ghadiali SN. Finite element analysis of traction force microscopy: influence of cell mechanics, adhesion, and morphology. J Biomech Eng. 2013;135:71009–710099. doi: 10.1115/1.4024467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orr-Urtreger A, Lonai P. Platelet-derived growth factor-A and its receptor are expressed in separate, but adjacent cell layers of the mouse embryo. Development. 1992;115:1045–1058. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.4.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinck L, Silberstein GB. Key stages in mammary gland development: The mammary end bud as a motile organ. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:245–251. doi: 10.1186/bcr1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bocchinfuso WP, Lindzey JK, Hewitt SC, Clark JA, Myers PH, Cooper R, Korach KS. Induction of Mammary Gland Development in Estrogen Receptor-alpha Knockout Mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2982–2994. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.8.7609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mueller SO, Clark JA, Myers PH, Korach KS. Mammary Gland Development in Adult Mice Requires Epithelial and Stromal Estrogen Receptor Alpha. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2357–2365. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mikaelian I, Hovick M, Silva KA, Burzenski LM, Shultz LD, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Cox GA, Sundberg JP. Expression of Terminal Differentiation Proteins Defines Stages of Mouse Mammary Gland Development. Vet Pathol. 2005;43:36–49. doi: 10.1354/vp.43-1-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tolg C, Yuan H, Flynn SM, Basu K, Ma J, Tse KC, Kowalska B, Vulkanesku D, Cowman MK, McCarthy JB. Hyaluronan modulates growth factor induced mammary gland branching in a size dependent manner. Matrix Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Insua-Rodriguez J, Oskarsson T. The extracellular matrix in breast cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;97:41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.12.017. [in press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lillie RD. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, MD, USA: 1977. H.J. Conn's Biological Stains. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levick JR. Flow through interstitium and other fibrous matrices. Q J Exp Physiol. 1987;72 doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1987.sp003085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jain RK, Martin JD, Stylianopoulos T. The role of mechanical forces in tumor growth and therapy. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2014;16:321–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071813-105259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fenner J, Stacer AC, Winterroth F, Johnson TD, Luker KE, Luker GD. Macroscopic Stiffness of Breast Tumors Predicts Metastasis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5512. doi: 10.1038/srep05512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mouw JK, Yui Y, Damiano L, Bainer RO, Lakins JN, Acerbi I, Ou G, Wijekoon AC, Levental KR, Gilbert PM. Tissue mechanics modulate microRNA-dependent PTEN expression to regulate malignant progression. Nat Med. 2014;20:360–367. doi: 10.1038/nm.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubashkin MG, Cassereau L, Bainer R, DuFort CC, Yui Y, Ou G, Paszek MJ, Davidson MW, Chen YY, Weaver VM. Force Engages Vinculin and Promotes Tumor Progression by Enhancing PI3K Activation of Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-Triphosphate. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4597–4611. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei SC, Fattet L, Tsai JH, Guo Y, Pai VH, Majeski HE, Chen AC, Sah RL, Taylor SS, Engler AJ. Matrix stiffness drives epithelial–mesenchymal transition and tumour metastasis through a TWIST1–G3BP2 mechanotransduction pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:678–688. doi: 10.1038/ncb3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fata JE, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Regulation of mammary gland branching morphogenesis by the extracellular matrix and its remodeling enzymes. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;6:335. doi: 10.1186/bcr634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Polyak K, Kalluri R. The Role of the Microenvironment in Mammary Gland Development and Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003244. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schedin P, Keely PJ. Mammary Gland ECM Remodeling, Stiffness, and Mechanosignaling in Normal Development and Tumor Progression. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;3:a003228. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jose AU, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and their expression in mammary gland. Cell Res. 1998;8:187–198. doi: 10.1038/cr.1998.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muschler J, Streuli CH. Cell-Matrix Interactions in Mammary Gland Development and Breast Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003202. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sternlicht MD. Key stages in mammary gland development: The cues that regulate ductal branching morphogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;8 doi: 10.1186/bcr1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stute P, Sielker S, Wood CE, Register TC, Lees CJ, Dewi FN, Williams JK, Wagner JD, Stefenelli U, Cline JM. Life stage differences in mammary gland gene expression profile in non-human primates. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:617–658. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1811-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krenning G, Zeisberg EM, Kalluri R. The origin of fibroblasts and mechanism of cardiac fibrosis. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:631–637. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meng X-M, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Lan HY. Inflammatory processes in renal fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10:493–503. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noble PW, Barkauskas CE, Jiang D. Pulmonary fibrosis: patterns and perpetrators. J Clin Investig. 2012;122:2756–2762. doi: 10.1172/JCI60323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lisanti MP, Reeves K, Peiris-Pagès M, Chadwick AL, Sanchez-Alvarez R, Howell A, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F. JNK1 stress signaling is hyper-activated in high breast density and the tumor stroma: Connecting fibrosis, inflammation, and stemness for cancer prevention. Cell Cycle. 2013;13:580–599. doi: 10.4161/cc.27379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lochter A, Galosy S, Muschler J, Freedman N, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Matrix Metalloproteinase Stromelysin-1 Triggers a Cascade of Molecular Alterations That Leads to Stable Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Conversion and a Premalignant Phenotype in Mammary Epithelial Cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1861–1872. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cox TR, Rumney RMH, Schoof EM, Perryman L, Høye AM, Agrawal A, Bird D, Latif NA, Forrest H, Evans HR. The hypoxic cancer secretome induces pre-metastatic bone lesions through lysyl oxidase. Nature. 2015;522:106–110. doi: 10.1038/nature14492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 65.Paszek MJ, DuFort CC, Rossier O, Bainer R, Mouw JK, Godula K, Hudak JE, Lakins JN, Wijekoon AC, Cassereau L. The cancer glycocalyx mechanically primes integrin-mediated growth and survival. Nature. 2014;511:319–325. doi: 10.1038/nature13535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material