Abstract

Meckel–Gruber syndrome (MGS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder which is characterized by a classic triad of occipital encephalocele, polycystic kidneys and postaxial polydactyly. We describe a case of classic MGS, diagnosed on ultrasonography and genetic analysis, with subsequent confirmation and correlation by fetal autopsy.

Keywords: Meckel–Gruber syndrome, Fetal autopsy, Ultrasonography

Sommario

La sindrome di Meckel–Gruber (MGS) è una rara anomalia autosomatica recessiva caratterizzata dalla triade classica composta da encefalo occipitale, reni policistici e polidattilìa postassiale. Descriviamo un caso di MGS classica, diagnosticata con ecografia ed analisi genetiche, successivamente confermata dal test autoptico del feto.

Introduction

Meckel–Gruber syndrome (MGS) is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by at least two of the three classic manifestations renal cystic dysplasia, occipital encephalocele or any other central nervous system anomaly and postaxial polydactyly. The disease is commonly fatal perinatally or in early infancy. Although MGS is a well-reported entity in the literature, the ultrasonographic and fetal autopsy correlation is uncommonly described [1–8]. The authors report a case of MGS which was suspected on ultrasonography, following which the pregnancy was terminated and the findings were further confirmed by fetal autopsy.

Case report

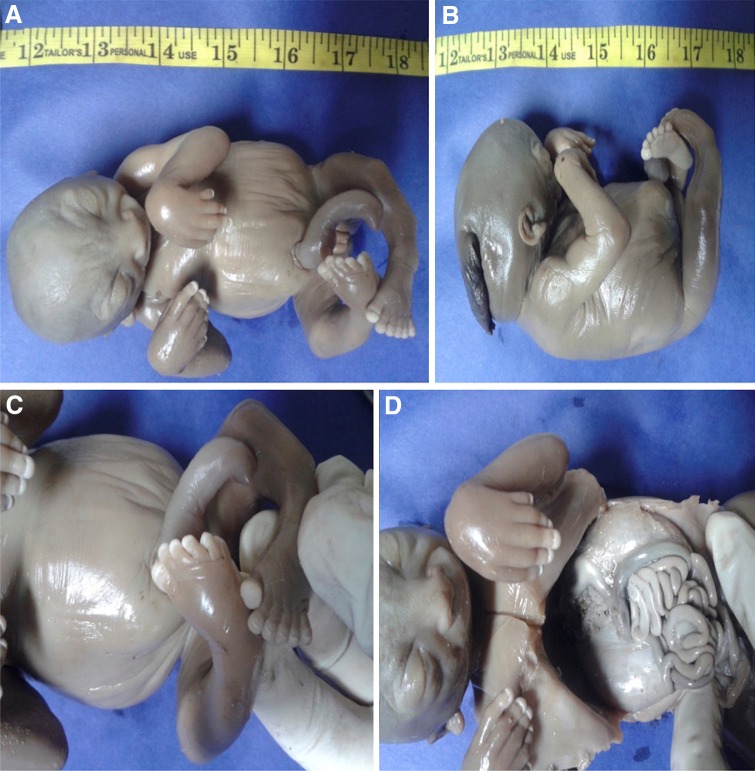

A 26-year-old woman with 17 weeks of gestation from a consanguineous marriage presented to the antenatal clinic with an ultrasonography report which revealed a single intrauterine pregnancy with occipital encephalocele (Fig. 1) and enlarged polycystic kidneys. The history was not suggestive of any teratogenic drug intake or exposure. After discussing the prognosis, the patient opted for termination of pregnancy. An informed consent was obtained from the patient for the procedure and fetal autopsy along with histopathological examination of the specimens. Placental biopsy was taken, and the sample was sent for molecular diagnosis. A frameshift mutation was identified in the sample with two pathogenic copies of TCTN1 gene, which was also identified in the blood samples taken from the parents. After termination of pregnancy, the fetus was sent for autopsy which showed a female fetus weighing 350 grams. On gross examination, the fetus showed occipital encephalocele with large protruding eyes, short neck and postaxial polydactyly in all limbs (Fig. 2). The X-ray of the terminated fetus showed shortening and significant bowing of the limbs (Fig. 3). The fetal kidneys were sent for histopathological examination which showed the presence of multiple cysts (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Prenatal ultrasound at 17 weeks showing echogenic occipital encephalocele

Fig. 2.

Autopsy of the fetus demonstrating a distended abdomen, b occipital encephalocele, c polydactyly and d bilaterally enlarged kidneys

Fig. 3.

X-ray of the terminated fetus showing shortening and bowing of the limbs

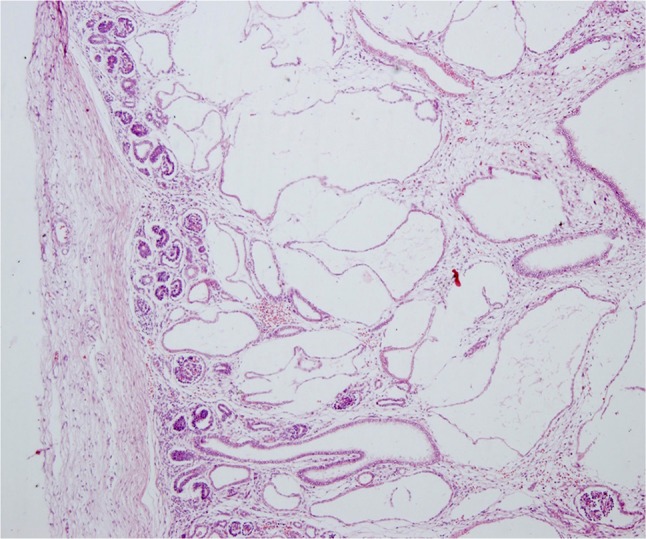

Fig. 4.

Histopathology of the kidney showing multiple cystic renal dysplasia (H&E, ×40)

Discussion

Meckel–Gruber syndrome is a rare genetic lethal malformation with a worldwide incidence varying from 1/140,000 (Great Britain) to 1/3500 (North Africa) in live births [9]. A higher incidence is recorded in Gujarati Indians (1 affected birth per 1304 with a carrier rate of 1 in 18) [10]. It was first described in 1822 by Meckel JF in a pair of siblings with occipital meningo-encephalocele, polycystic kidneys, polydactyly, microcephaly and cleft palate [11]. In 1934, Gruber GB further described 16 fetuses with polycystic kidneys, polydactyly, occipital encephalocele and microphallus as demonstrating dysencephalia splanchnocystica [12]. The identity of this syndrome, however, was not established until 1969, when Opitz and Howe [13] proposed the name Meckel syndrome and delineated its clinical and pathologic features.

The central nervous system anomalies may range from the classic occipital exencephalocele to prosencephalic dysgenesis, rhombic roof dysgenesis, microcephaly, cerebellar hypoplasia, cranial rachischisis, hydrocephalus, polymicrogyria and Dandy–Walker malformation [14, 15]. MGS is most commonly characterized by polycystic kidneys, occipital encephalocele and polydactyly with a reported prevalence of 100, 90 and 83.3%, respectively [16]. The excessively large, cystic, dysplastic kidneys cause marked abdominal distention. Other genitourinary anomalies may include agenesis, atresia, hypoplasia and duplication of ureters, severe hypoplasia of male genitalia with cryptorchidism, epididymal cysts and the absence or hypoplasia of urinary bladder. Ductal plate malformation is common in the liver with fibrosis, and proliferation of the bile ducts in the hepatic portal tracts and fibrocystic changes of the pancreas have also been associated with MGS [16, 17]. Facial anomalies such as cleft lip, high arched palate and hypertelorism are also observed in many cases [14]. Skeletal malformations may also include shortening and bowing of long tubular bones and club feet (Fig. 4). Cardiac anomalies like atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect or a patent ductus arteriosus may be present. These findings can be confirmed on fetal autopsy and genetic study [1].

On histological examination, the cysts are spherical and lined by single-layered cuboidal epithelium, glomeruli are absent, and interstitial fibrosis is prominent. Occasionally, the liver may show proliferation and dilation of the bile ducts, alongside an excess of collagenous connective tissues. The encephalocele contains disorganized glial tissue with ependymal-like epithelium and thickened meninges with many congested blood vessels [18].

The maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein levels may be elevated as a result of encephalocele or other neural tube defects by 12 weeks of gestation [19].

Meckel–Gruber syndrome is among the broader range of ciliopathies known so far, including autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and Joubert syndrome (JBTS). Although MGS has been commonly reported in consanguineous marriages, it has been known to occur in fetuses from non-consanguineous marriages as well, pointing to the presence of locus heterogeneity and allelism with a marked variability of phenotypes. Recently, up to 12 mutations have been identified and mapped to different loci on several chromosomes, the most prominent among these being MKS1-3 [20]. These genes encode proteins and their complexes (for instance tectonic TCTN 1 transmembrane protein) that are important in tissue-targeted ciliogenesis during embryonic development, for example, the Sonic Hedgehog signaling for neural tube development.

The ultrasonographic features in the late first and early second trimester consistent with the diagnosis include [21–25] the following:

A disproportionately large and protuberant abdomen with unusual heterogeneous cortico-medullary junction and large hypoechoic medullary areas, consistent with 2–10 mm cysts and an estimated renal volume larger than 95th percentile for age for all fetuses. The fetal bladder may or may not be visualized. This results in mild to moderate oligohydramnios by 17th week of gestation in most of the cases.

The central nervous system anomalies may range from a small abnormal anechoic cystic intracranial image to a bony defect in the occipital vault leading to a protruding brain and meninges, which may be associated with Dandy–Walker malformation in some cases.

Polydactyly in the limbs may be reported in meticulously performed sonograms, until the amniotic fluid levels are normal. Other features like cleft palate, cystic hepatic lesions, external genital defects and single umbilical artery may also be visualized.

However, difficulty may be encountered in differentiating mild MGS from severe Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome (microcephaly, mental retardation and polydactyly), the hydrolethalus (Salonen–Herva–Norio) syndrome (duplicated big toe, micrognathia, hydrocephaly with absent midline structures of the brain), trisomy 13 (holoprosencephaly, cleft lip/palate, congenital heart diseases and polydactyly), Joubert syndrome (hypoplasia/dysplasia of vermis, facial abnormalities, cystic renal diseases, polydactyly and cleft palate), Bardet–Biedl syndrome (vision loss, mental retardation, renal diseases, polydactyly and cleft palate) and Ivemark syndrome.

Conclusion

With 100% fetal or neonatal mortality and a high (25%) recurrence rate in pregnancy, a precise early diagnosis of MGS at 11–14 weeks by transvaginal ultrasound is vital for obstetric management. Ultrasound positively correlates with fetal autopsy findings. Parents should undergo genetic counseling for future pregnancies.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study involves postmortem autopsy of the fetal human specimen. No animals were involved in the study.

Informed consent

An informed consent was obtained from the patient for the termination of pregnancy, fetal autopsy and histopathological examination of the specimens.

Contributor Information

Shruti Khurana, Phone: +1 713 427 1929, Email: shruti.khurana225@gmail.com.

Vikram Saini, Email: vsaini4@jhmi.edu.

Vibhor Wadhwa, Email: vibhorwadhwa90@gmail.com.

Harveen Kaur, Email: harveen.lhmc.2005@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Panduranga C, Kangle R, Badami R, Patil PV. Meckel–Gruber syndrome: report of two cases. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3:56–59. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.91943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CP. Meckel syndrome: genetics, perinatal findings and differential diagnosis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46:9–14. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60100-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hakverdi S, Güzelmansur I, Sayar H, Arif G, Hakverdi AU, Toprakl S. Meckel–Gruber syndrome: a report of three cases. Perinat J. 2010;18:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myageri A, Grampurohit V, Rao R. Meckel Gruber syndrome: report of two cases with review of literature. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2013;2:106–108. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.109971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gazioglu N, Vural M, Seçkin MS, Tüysüz B, Akpir E, Kuday C, Ilikkan B, Erginel A, Cenani A. Meckel–Gruber syndrome. Childs Nerv Syst. 1998;14:142–145. doi: 10.1007/s003810050198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones KL (2006) Meckel–Gruber syndrome. In: Jones KL (ed) Smith’s recognizable patterns of human malformation. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 18–19, 114–115, 198, 204, 292–293

- 7.Bolineni C, Nagamuthu EA, Neelala N. Fetal autopsy of Meckel Gruber syndrome—a case report. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2013;32:387–393. doi: 10.3109/15513815.2013.768741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy J, Pal M. Meckel Gruber syndrome. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2102–2103. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5946.3421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seller MJ. Meckel syndrome and the prenatal diagnosis of neural tube defects. J Med Genet. 1978;15:462–465. doi: 10.1136/jmg.15.6.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young ID, Rickett AB, Clarke M. High incidence of Meckel’s syndrome in Gujarati Indians. J Med Genet. 1985;22:301–304. doi: 10.1136/jmg.22.4.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meckel JF. Beschreibung zweier, durch sehr ahnliche bildungsabweichungen entstelter geschwister. Dtsch Arch Physiol. 1822;7:99–172. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruber BG. Beiträge zur frage “gekoppelter” missbildungen. (Acrocephalo-Syndactylie und Dysencephalia splanchnocystica) Beitr Path Anat. 1934;93:459–476. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opitz JM, Howe J. The Meckel syndrome (dysencephalia splanchnocystica, the Gruber syndrome) In: Bergsma D, editor. Malformation syndromes. New York: The National Foundation/Williams & Wilkins; 1969. pp. 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahdab-Barmada M, Claassen D. A distinctive triad of malformations of the central nervous system in the Meckel–Gruber syndrome. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1990;49:610–620. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199011000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexiev BA, Lin X, Sun CC, Brenner DS. Meckel–Gruber syndrome pathologic manifestations, minimal diagnostic criteria, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1236–1238. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1236-MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sergi C, Adam S, Kahl P, Otto HF. Study of the malformation of the ductal plate of the liver in Meckel syndrome and review of other syndromes presenting with this anomaly. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2000;3:568–583. doi: 10.1007/s100240010104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salonen R. The Meckel syndrome: clinico-pathological findings in 67 patients. Am J Med Genet. 1984;18:671–689. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320180414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chao A, Wong AM, Hsueh C, Chang YL, Wang TH. Integration of imaging and pathological studies in Meckel–Gruber syndrome. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:267–268. doi: 10.1002/pd.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sepulveda W, Sebire NJ, Souka A, Snijders RJ, Nicolaides KH. Diagnosis of Meckel Gruber syndrome at eleven to fourteen weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:316–319. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70491-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank V, Ortiz Brüchle N, Mager S, Frints SG, Bohring A, du Bois G, Debatin I, Seidel H, Senderek J, Besbas N, Todt U, Kubisch C, Grimm T, Teksen F, Balci S, Zerres K, Bergmann C. Aberrant splicing is a common mutational mechanism in MKS1, a key player in Meckel–Gruber syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:638–639. doi: 10.1002/humu.9496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ickowicz V, Eurin D, Maugey-Laulom B, Didier F, Garel C, Gubler MC, Laquerrière A, Avni EF. Meckel–Grüber syndrome: sonography and pathology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:296–300. doi: 10.1002/uog.2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyberg DA, Hallesy D, Mahony BS, Hirsch JH, Luthy DA, Hickok D. Meckel–Gruber syndrome. Importance of prenatal diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med. 1990;9:691–696. doi: 10.7863/jum.1990.9.12.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pachì A, Giancotti A, Torcia F, de Prosperi V, Maggi E. Meckel–Gruber syndrome: ultrasonographic diagnosis at 13 weeks’ gestational age in an at-risk case. Prenat Diagn. 1989;9:187–190. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970090307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braithwaite JM, Economides DL. First-trimester diagnosis of Meckel–Gruber syndrome by transabdominal sonography in a low-risk case. Prenat Diagn. 1995;15:1168–1170. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970151215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vernekar JA, Mishra GK, Pinto RG, Bhandari M, Mishra M. Antenatal ultrasonic diagnosis of Meckel Gruber syndrome (a case report with review of literature) Australas Radiol. 1991;35:186–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1991.tb02864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]