Highlights

-

•

Actinomycosis represents only the 0.02% of causes of acute apendicitis.

-

•

We present the first case of appendiceal actinomycosis reported in México.

-

•

As to our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature with appendiceal actinomycosis without been perforated.

Keywords: Actinomycosis, Appendicular actinomycosis, Abdominal actinomycosis, Subacute appendicitis

Abstract

Introduction

Acute appendicitis is the most common indication for an emergency abdominal surgery in the world, with a lifetime incidence of around 10%. Actinomycetes are the etiology of appendicitis in only 0.02%–0.06%, having as the final pathology report a chronic inflammatory response; less than 10% of the cases are diagnosed before surgery. Here, we present the case of a subacute appendicitis secondary to actinomycosis.

Case report

A 39-year-old male presented with a twelve-day evolution of intermittent abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant, treated at the beginning with ciprofloxacin and urinary analgesic. The day of the admission he referred intense abdominal pain with nausea. An open appendectomy was preformed, finding a tumor-like edematous appendix with a diameter of approximately 2.5 cm.

Discussion

Actinomyces are part of the typical flora of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract and vagina. The predominant form of human disease is A. Israelii, it requires an injury to the normal mucosa to penetrate and cause disease. Abdominal actinomycosis involves the appendix and caecum in 66% of the presentations, of these, perforated appendicitis is the stimulus in 75% of the cases. A combination of antibiotic therapy and operative treatment resolves actinomycosis in 90% of cases.

Conclusion

Abdominal actinomycosis is an uncommon disease been the common presentation a perforated appendicitis, here we present a less common presentation of it with a non-perforated appendix.

1. Introduction

Acute appendicitis is the most common indication for an emergency abdominal surgery in the world, with a lifetime incidence of around 10% [1], [2]. The etiology of acute appendicitis is secondary to appendiceal obstruction, the commonest causes of this obstruction are lymphoid hyperplasia and, fecal stasis with fecaliths [3], [4], [5]; other rare causes have been described such as carcinoid tumor of the appendix, pinworm, eosinophilic appendicitis, granulomas, and actinomycosis among others [3], [5], [6].

Actinomycosis species are gram-positive bacteria, which are normal commensals of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal, and urogenital tract, but become pathogenic in the presence of necrotic tissue [7], [8], [9]. It is reported, that actinomycetes are the etiology of appendicitis in only 0.02%–0.06% [3], [5], [6], having as the final pathology report a chronic inflammatory response. The usual clinical scenario is an indolent course with unspecific symptoms and signs, and less than 10% of the cases are diagnosed before surgery [8], [9], [10]. Here, we present the case of a subacute appendicitis secondary to actinomycosis. The following accomplishes the SCARE criteria [11].

2. Case presentation

A 39-year-old male presented to the emergency room with a twelve-day evolution of intermittent abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant, treated at the beginning with ciprofloxacin and urinary analgesic like a urinary tract infection.

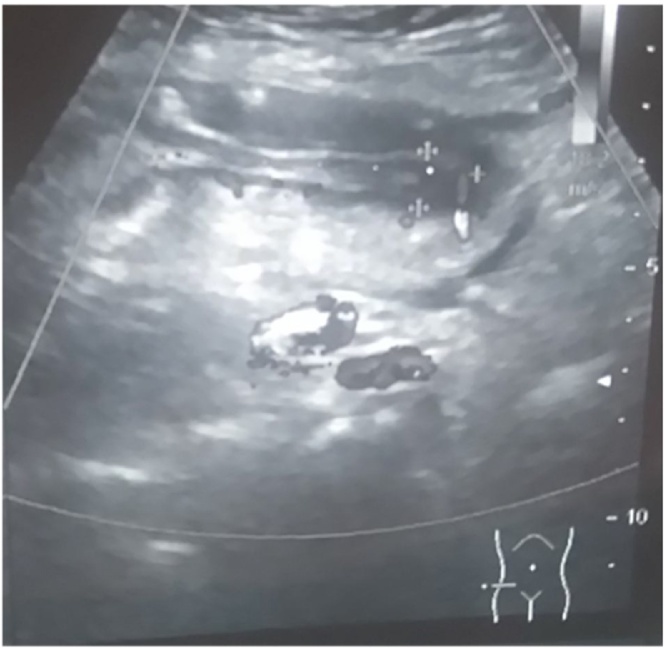

Three days before surgery his symptoms got worse, started with fever, nausea, and vomiting. The day of the admission he referred intense abdominal pain with nausea. On physical examination the patient was in bad shape with a temperature of 38.5 °C, the abdomen was tenderness with Blumberg and McBurney signs presents, no palpable mass detected. The patient showed an abdominal ultrasound where free liquid in the right iliac fossa was seen, the cecal appendix measured 58 × 10 × 11 mm, was non-compressible, with peri-appendicular edema (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Abdominal ultrasound is showing the appendix between the marks with peri-appendicular edema.

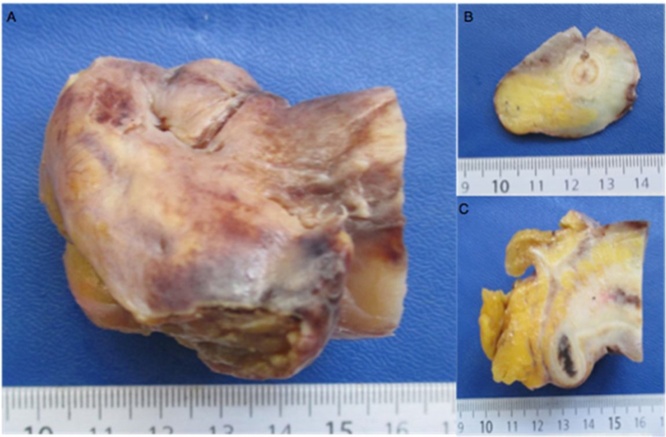

The patient was admitted to the operating room for an open appendectomy. The appendix was located in a pelvic position; it was tumor-like edematous with a diameter of approximately 2.5 cm. We did a Parker Kerr technique, without complications. The patient had a normal evolution and was discharged on the second postoperative day with oral antibiotic treatment.

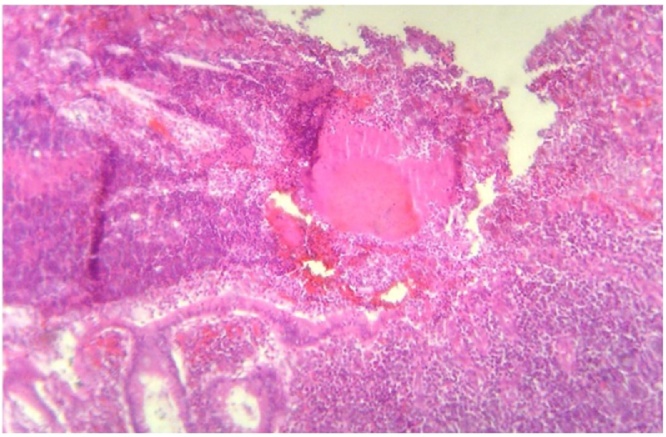

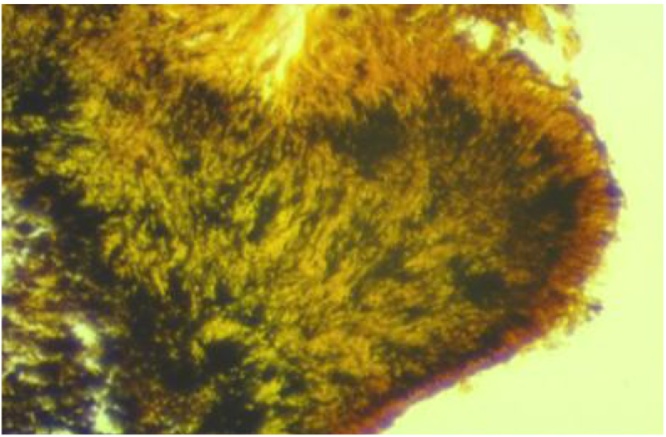

The pathology report showed chronic fistulized appendicitis with transmural lymphoid infiltration (Fig. 2), the presence of sulfur granules compatible with actinomycosis (Fig. 3), and silver staining with filamentous bacilli dyed black (Fig. 4). Six months after surgery there is no complaints or recurrence of actinomycosis, he is currently under treatment.

Fig. 2.

(A) Tip of the appendix. (b) Fistulous path and (C) fibrous formation around the appendix.

Fig. 3.

Typical sulfur granule surrounded by an acute inflammatory process with ulceration of the mucosa. (HE 100×).

Fig. 4.

Silver staining showing filamentous bacilli dyed black (Warhin–Starry 100×).

3. Discussion

In 1886, Reginald Fitz described the physiopathology of the acute appendicitis; in 1999, Stevenson [12] introduced the term appendiceal colic and chronic appendicitis. Only 1% of patients with appendicitis had symptoms for more than a week [13]; the non-acute variants of appendicitis, includes recurrent, subacute, and chronic appendicitis, which are rarely diagnosed and remain subjects of case reports [14]. Chronic appendicitis, is a rare entity, that should be suspected in patients with more than seven days with abdominal pain in the right iliac fossa (generally at least two to three weeks) [4], [14], [15]; its precise etiology is unknown, recurrent appendicitis is thought to occur from transient obstruction of the appendix or secondary to excessive mucus production, while chronic appendicitis is secondary to partial but persistent obstruction of the appendiceal lumen [15].

Limaiem et al. [6], reported in a retrospective study of 1627 cases of appendectomy specimens, only one sample had actinomycosis (0.06%). Cunningham et al. [5], found that only two patients in their series of 4236 samples, had actinomycosis, that represents 0.04%. Alemayehu et al. [3], studied 3602 appendicular samples, and only one of them had actinomycosis (0.02%).

The overall incidence of actinomycosis is virtually unknown; the estimated population prevalence is one case per 40–119,000 [8]. Actinomyces are part of the typical flora of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract and vagina, been gram-positive bacteria, nonsporing absolute or facultative anaerobes that require an anaerobic carbon dioxide rich medium for culture [7], [8], [9], [16]. The predominant form of human disease is A. Israelii, with occasional cases caused by A. Naeslundii, Odontolyticus Viscosus or Meyeri [4], [7], [8], [16]; it requires an injury to the normal mucosa to penetrate and cause disease; such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, gastrointestinal perforations, previous surgery, foreign bodies, or neoplasia [7], [8], [9], [10].

The peak incidence of actinomycosis is reported to occur in middle-aged individuals [9], [17], although, is described that is more frequent in men with a relation M:F of 3:1 [7], [8], the largest cases series that we found of abdominal actinomycosis by Choi et al. [10] reported 22 cases of abdominopelvic actinomycosis, with an M:F ratio of 1:10. They found an association with the use of an intrauterine device with the presence of the disease (60%).

Actinomycosis commonly occurs in three distinct forms that may occasionally overlap, cervicofacial presentation in 50%, abdominopelvic in 20%, and intrathoracic form in 15% [7], [8], [9]. Abdominal actinomycosis involves the appendix and caecum in 66% of the presentations [18], [19], of these, perforated appendicitis is the stimulus in 75% of the cases [19]; therefore, as in our case, the disease is rarely found in an inflamed but intact appendix [8]. Clinical presentation has an indolent course, with an initial nonspecific presentation, usually with lower abdominal pain and fever, with less than 10% of the cases diagnosed before surgery [8], [9], [10]. Careful examination of the abdomen may reveal tenderness, and a palpable mass only in few cases. A history with similar symptoms 2–3 weeks before the presentation of the patient is suggestive of missed perforated appendicitis. [9], [10]. Radiologic techniques are not helpful in the diagnosis of abdominal actinomycosis; the abdominal CT scan may show an infiltrative mass (predominantly cystic or solid) adjacent to the other involved organs, been the bowel wall thickening the main sign of gastrointestinal disease [20]. The final diagnosis of actinomycosis requires microscopic proof of either the pathogen itself, the presence of specific “sulfur granules,” or culture of Actinomyces obtained by needle aspiration or from a surgical specimen [9], [17].

When uncomplicated abdominal actinomycosis is diagnosed without surgery, the medical treatment with antibiotics is indicated; the initial treatment is with intravenous penicillin G for 4–6 weeks, followed by oral penicillin V for 2–12 months [7], [9], [10], [20]. In this cases, CT scan is serve to monitor the effectiveness of the treatment [20]. Surgery is reserved for patients who do not respond to initial antibiotic therapy or for patients in whom there is a severe spread of the disease as noted by fistulas, necrosis or abscesses [7]. Antibiotic therapy should be given even if there is not a microbiological culture, as long as there is the presence of sulfur granules in the pathological report [20]. A combination of antibiotic therapy and operative treatment resolves actinomycosis in more than 90% of cases [7], [9], [17].

4. Conclusion

Chronic appendicitis is a rare entity, requiring a pathological report for the definitive diagnosis; without a precise etiology, the clinical presentation of a patient with more than seven days with abdominal pain should bring into the mind of the surgeon's pathologies less common, such as actinomycosis. Abdominal actinomycosis is an uncommon disease been the common presentation a perforated appendicitis, here we present a less common presentation of it with a non-perforated appendix. More cases with a good clinical and radiological description are needed to improve the preoperative diagnosis of abdominal actinomycosis. As to our knowledge, this is the first case of appendiceal actinomycosis reported in México [21], [22], [23], [24], [25].

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

The written consent was sign by the patient.

Consent

No personal information is given nor modified.

Author contribution

Gómez-Torres GA.—Study concept, writing the paper, final decision to publish, data collection.

Ortega-Garcia OS.—Study concept, data collection, writing the paper, final decision to publish.

Gutierrez-López EG.—Data collection and analysis.

Carballido-Murguía CA.—Data collection and analysis.

Flores-Rios JA.—Data collection, and analysis.

López-Lizarraga CR.—Data collection, and analysis.

Bautista López CA.—Data collection, and analysis.

Ploneda-Valencia CF.—Writing the paper, data collection, final decision to publish.

Guarantor

Gustavo Ángel Gómez Torres and César Felipe Ploneda-Valencia.

References

- 1.Sotelo-Anaya E., Sánchez-Muñoz M.P., Ploneda-Valencia C.F., de la Cerda-Trujillo L.F., Varela-Muñoz O., Gutiérrez-Chávez C. Acute appendicitis in an overweight and obese Mexican population: a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2016;32(August):6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Alvarez F.A., Maciel-Gutierrez V.M., Rocha-Muñoz A.D., Lujan J.H., Ploneda-Valencia C.F. Diagnostic value of serum fibrinogen as a predictive factor for complicated appendicitis (perforated). A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Surg. 2016;25(January):109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alemayehu H., Snyder C.L., St Peter S.D., Ostlie D.J. Incidence and outcomes of unexpected pathology findings after appendectomy. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014;49(September (9)):1390–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuri Osorio J.A., De Luna Díaz R., Marín D., Espinosa Aguilar L., Martínez Berlanga P. Chronic appendicitis of 3 years progression secondary to actinomycosis infection. Cir. Esp. 2012;90(February (2)):131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettiford Cunningham J., Gasior A., Knott E.M., Snyder C.L., St Peter S.D., Ostlie D.J. Incidence and outcomes of unexpected pathology findings after appendectomy. J. Surg. Res. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.005. [Internet]. 2012 November [cited 23 April 2017]; Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S002248041200964X (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limaiem F., Arfa N., Marsaoui L., Bouraoui S., Lahmar A., Mzabi S. Unexpected histopathological findings in appendectomy specimens: a retrospective study of 1627 cases. Indian J. Surg. 2015;77(December (Suppl. 3)):1285–1290. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad R.J., Riela S., Patel R., Misra S. Abdominal actinomycosis mimicking acute appendicitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;26(November) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-212888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garner J.P., Macdonald M., Kumar P.K. Abdominal actinomycosis. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2007;5(December (6)):441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu K., Joseph D., Lai K., Kench J., Ngu M.C. Abdominal actinomycosis presenting as appendicitis: two case reports and review. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2016;2016(May (5)) doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjw068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi M.-M., Baek J.H., Beak J.H., Lee J.N., Park S., Lee W.-S. Clinical features of abdominopelvic actinomycosis: report of twenty cases and literature review. Yonsei Med. J. 2009;50(August (4)):555–559. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2016;34(October):180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stevenson R.J. Chronic right-lower-quadrant abdominal pain: is there a role for elective appendectomy? J. Pediatr. Surg. 1999;34(June (6)):950–954. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90766-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawes A.S., Whalen G.F. Recurrent and chronic appendicitis: the other inflammatory conditions of the appendix. Am. Surg. 1994;60(March (3)):217–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berk D.R., Sylvester K.G. Subacute appendicitis. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila.) 2005;44(May (4)):363–365. doi: 10.1177/000992280504400414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kothadia J.P., Katz S., Ginzburg L. Chronic appendicitis: uncommon cause of chronic abdominal pain. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2015;8(May (3)):160–162. doi: 10.1177/1756283X15576438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennhoff D.F. Actinomycosis: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations and a review of 32 cases. Laryngoscope. 1984;94(September (9)):1198–1217. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198409000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yiğiter M., Kiyici H., Arda İ.S., Hiçsönmez A. Actinomycosis: a differential diagnosis for appendicitis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2007;42(June (6)):e23–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu V., Val S., Kang K., Velcek F. Case report: actinomycosis of the appendix—an unusual cause of acute appendicitis in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010;45(October (10)):2050–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshmukh N., Heaney S.J. Actinomycosis at multiple colonic sites. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1986;81(December (12)):1212–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S.-Y. Actinomycosis of the appendix mimicking appendiceal tumor: a case report. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16(3):395. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olvera-Reynada A., Calzada-Ramos M.A., Espinoza-Guerrero X., Molotla-Xolalpa C., Cervantes-Miramontes P.J. Actinomicosis abdominal. Presentación de tres casos. Cir. Cir. 2005;73:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guevara-López J.A., Aragón-Quintana C., Rodríguez-Zamacona A. Actinomicosis de colon: forma rara de abdomen agudo: Reporte de caso. Rev. Espec. Méd.—Quirúrgicas. 2015;20(1):90–93. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rojas Pérez-Ezquerra B., Guardia-Dodorico L., Arribas-Marco T., Ania-Lahuerta A., González Ballano I., Chipana-Salinas M. Actinomicosis de pared abdominal. A propósito de un caso. Cir. Cir. 2015;83(March (2)):141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.circir.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanco-Vela C.I., Luna-Ayala V.M., Perez-Aguirre J. Colonic mass secondary to actinomycosis: a case report and literature review. Rev. Gastroenterol. Mex. 2014;79(September (3)):206–208. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmx.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flores-Franco R.A., Lachica-Rodriguez G.N., Banuelos-Moreno L., Gomez-Diaz A. Spontaneous peritonitis attributed to actinomyces species. Ann. Hepatol. 2007;6(December (4)):276–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]