Abstract

Objective:

This study sought to confirm a previously identified race by sexual orientation interaction and to clarify men’s alcohol-related risk by using an expanded classification of sexual orientation.

Method:

We collapsed three waves of National Alcohol Survey data, restricting the analytic sample to White (n = 5,689), Black (n = 1,237), and Latino (n = 1,549) men with complete information on sexual orientation and alcohol use. Using self-reported sexual identity and behavior, respondents were categorized as exclusively heterosexual (referent), behaviorally discordant heterosexuals (i.e., heterosexual identity and same-sex partners), or gay/bisexually identified men. We used multivariable logistic regression to model lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms, lifetime drinking-related consequences, and past-year hazardous drinking, controlling for age, education, employment, and relationship status and accounting for the complex survey design.

Results:

There was no difference in risk of past-year hazardous drinking and lifetime drinking-related consequences between heterosexual, behaviorally discordant heterosexual, and gay/bisexual men, independent of race/ethnicity. Among Black men, behaviorally discordant heterosexuals had three-fold higher odds of lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms than exclusively heterosexual peers (aOR = 3.30, 95% CI [1.19, 9.18], p = .02). Gay/bisexual Latino men had marginally significantly lower odds of lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms (aOR = 0.36, 95% CI [0.12, 1.03], p = .06).

Conclusions:

There is little support for broad statements of greater alcohol risk among gay/bisexual men; however, for some subgroups and outcomes the direction and degree of risk depend on race/ethnicity. Thus, this study underscores the importance of considering the potential interaction of sexual orientation and race/ethnicity, which may exacerbate or attenuate alcohol-related risk.

Early alcohol research on gay and bisexual men found consistently high levels of alcohol misuse; however, these studies suffered from a number of methodological limitations, such as small samples recruited via nonprobability methods, poorly operationalized definitions of sexual orientation, and a lack of appropriate comparison groups (Fifield, 1975; Lohrenz et al., 1978; Saghir & Robins, 1973). Several recent studies using probability sampling and standardized measures of sexual orientation found evidence of greater risk of alcohol misuse among gay and bisexual men. For example, a population-based study based on the 2000 National Alcohol Survey found that more gay men reported past-year heavy drinking than did heterosexual men (Drabble et al., 2005). A similar study examining Wave 2 of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions found no difference for heavy drinking, but gay and bisexual men had two to four times higher odds of past-year alcohol dependence than heterosexual men (McCabe et al., 2009). Focusing on college students, Kerr and colleagues (2014) found that gay and bisexual men had higher odds of both any alcohol use and drinking-related consequences than heterosexual men. Dermody et al. (2014) analyzed four waves of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, finding that during the transition to young adulthood gay and bisexual adolescent males’ risk of heavy drinking increases faster than their heterosexual peers’ risk. Although these studies included race/ethnicity as a covariate, no analysis explored differences by race/ethnicity within sexual orientation categories.

Concurrently there have also been numerous reports of null findings. In an analysis of National Household Survey on Drug Abuse data by sexual behavior, Cochran et al. (2000) found no differences in the proportion of current drinkers or risk of alcohol dependence between men reporting any past-year male sex partners and exclusively heterosexual counterparts. A later analysis of the National Latino and Asian American Survey drew upon both sexual identity and sexual behavior measures (Cochran et al., 2007), showing no difference in the risk of past-year and lifetime alcohol abuse/dependence between sexual minority and heterosexual men. An investigation of drinking contexts using National Alcohol Survey data and both sexual identity and behavior measures found that a larger proportion of gay men reported attending bars compared with bisexual men, heterosexually identified men with same-sex partners, and exclusively heterosexual men. However, there was no difference between the groups in the average number of drinks consumed in any context (Trocki et al., 2005). In one of the few studies to distinguish rural and nonrural settings, Farmer and colleagues (2016) analyzed data from 10 states in the 2010 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey. Based on sexual identity, the study found no difference in the risk of heavy drinking for gay and bisexual men compared with heterosexual men, regardless of setting. Finally, combining four waves of California Health Interview Survey data, Boehmer et al. (2012) found higher odds of any current alcohol use among gay men but no differences in the risk of heavy episodic drinking (HED) among gay or bisexual men compared with heterosexual peers. As above, none of these studies explored differences by race/ethnicity within sexual orientation categories, despite large and diverse samples.

In addition, some recent studies found that certain subgroups of sexual minority men may be at lower risk for alcohol misuse. For example, McCabe and colleagues (2005) analyzed an online survey of students at a large midwestern university, finding that bisexually identified men and those attracted mostly to men had lower odds of HED than heterosexually identified men and those attracted exclusively to women. Similarly, Jasinski and Ford (2007), using the 2001 College Alcohol Study, found that greater proportions of heterosexual men reported HED than gay and bisexual peers. In sum, hazardous drinking varies among men who have sex with men, who cannot be presumed to always have greater risk.

A potential explanation of mixed findings may be the multiple dimensions of sexual orientation, including attraction, behavior, and identity (Sexual Minority Assessment Research Team [SMART], 2009). The use of multidimensional measures now permits examination of discordant sexual identity and behavior, such as reporting both a heterosexual identity and same-sex sexual behavior. Discordance between sexual identity and behavior is not uncommon and appears to vary by gender and race/ethnicity (Chandra et al., 2011; Igartua et al., 2009; Ross et al., 2003); however, limited research precludes stable prevalence estimates. Among recent work, one analysis of a regional sample of sexual minority women found that discordance between sexual identity and behavior was a risk factor for hazardous drinking (Talley et al., 2015). In contrast, an analysis of a national sample of men found that discordance between sexual identity and behavior was associated with a lower risk of lifetime alcohol use disorder compared with both heterosexual and gay identified peers (Gattis et al., 2012).

As it has been widely observed that greater proportions of Blacks and Latinos abstain from alcohol than their White counterparts and that heavy drinking trajectories differ for racial/ethnic minority men (Chartier & Caetano, 2010;

Dawson et al., 1995; Galvan & Caetano, 2003), a previous study by Gilbert and colleagues (2015) investigated whether the association between sexual orientation and hazardous drinking might be conditional on race/ethnicity. Analyzing data from White, Black, and Latino men in Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, the authors compared exclusively heterosexual men to men who self-identified as gay, bisexual, or heterosexual with same-sex partners, finding an enhanced protective effect for Black and Latino sexual minority men, who were at lower risk for heavy and binge drinking than both White heterosexual men and same-race/ethnicity heterosexual men. To our knowledge, there have been no other formal tests of a race by sexual orientation interaction reported in the literature. Given the indication of conditional associations, and recognizing that accurate epidemiological profiles are a necessary foundation of effective interventions to reduce risks, the goal of the present study was to confirm the earlier finding in an independent national data set and to clarify its effect by using an expanded classification of sexual orientation and more rigorously defined outcomes.

Both theory and empirical evidence shaped the study design. First, following models of stress-reactive drinking, we reasoned that gay and bisexually identified men would be subject to similar social stressors because of minority sexuality and would resemble each other more than heterosexually identified groups. Thus, they were combined in a single group for analysis. Second, based on results reported by Gilbert and colleagues (2015), we hypothesized that sexual minority men would have equivalent or lower risk of hazardous drinking compared with heterosexual peers and that there would be an interaction with race/ethnicity such that there would be lower risk among Black and Latino sexual minority men than White peers. In addition, we investigated alcohol-related risk among men who identified as heterosexual but had same-sex sexual partners (i.e., behaviorally discordant heterosexual men), differentiating them from exclusively heterosexual and gay or bisexually identified peers. Because few studies have investigated alcohol use among this subgroup of heterosexually identified men who have sex with men, we had no a priori hypothesis about the direction of any differences.

Method

Sample

We analyzed data from the National Alcohol Survey (NAS), a repeated cross-sectional study of alcohol consumption and related outcomes among adults age 18 years and older in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Since 1979, the NAS has been conducted approximately every 5 years, and since 2000, data have been collected using computer-assisted telephone interviews in English and

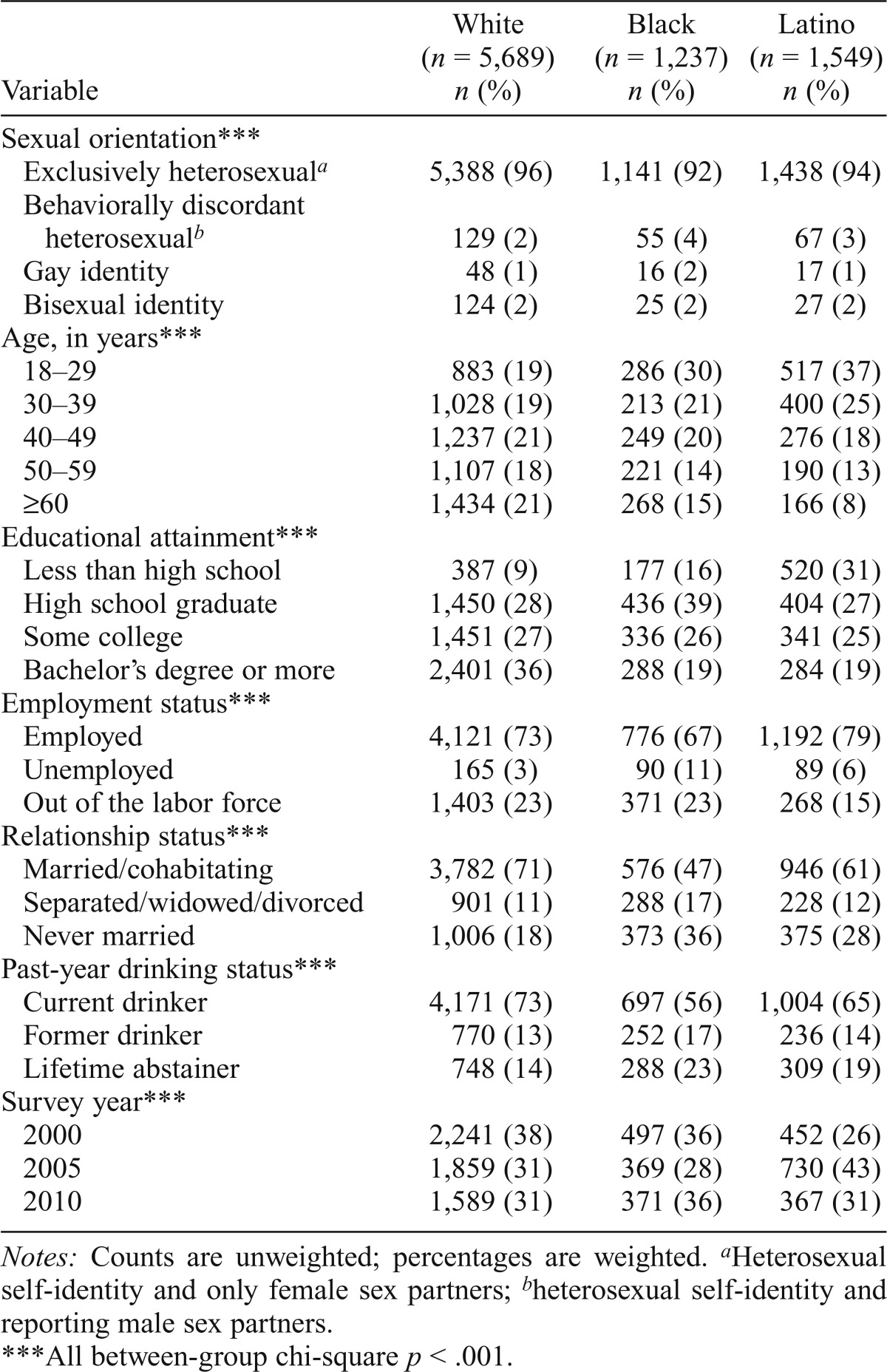

Spanish. Respondents were sampled using random-digit dialing, with oversampling of African Americans, Latinos, and low-population states. In 2000 and 2005, respondents were contacted exclusively through landlines. In 2010, they were contacted by landlines and cell phones; however, as the 2010 cell phone sample did not receive the full battery of sexual orientation items, we excluded those respondents from the analytic sample. To ensure adequate sample sizes of sexual minorities, the current study collapsed three waves of the NAS (2000, 2005, and 2010). To avoid problems associated with low frequencies of some racial/ethnic groups, we restricted the present study to non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic or Latino men of any race. Of 9,292 potential participants, we excluded men who were missing information about sexual orientation (n = 817, 9% of potential participants), and among the subset of current drinkers we excluded those who were missing information on alcohol outcomes (n = 50, <1% of potential participants). Characteristics of the full analytic sample (n = 8,475) are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of male respondents in three waves of the National Alcohol Survey (2000–2010) by race/ethnicity

| Variable | White (n = 5,689) n (%) | Black (n = 1,237) n (%) | Latino (n = 1,549) n (%) |

| Sexual orientation*** | |||

| Exclusively heterosexuala | 5,388 (96) | 1,141 (92) | 1,438 (94) |

| Behaviorally discordant heterosexualb | 129 (2) | 55 (4) | 67 (3) |

| Gay identity | 48 (1) | 16 (2) | 17 (1) |

| Bisexual identity | 124 (2) | 25 (2) | 27 (2) |

| Age, in years*** | |||

| 18–29 | 883 (19) | 286 (30) | 517 (37) |

| 30–39 | 1,028 (19) | 213 (21) | 400 (25) |

| 40–49 | 1,237 (21) | 249 (20) | 276 (18) |

| 50–59 | 1,107 (18) | 221(14) | 190 (13) |

| ≥60 | 1,434 (21) | 268 (15) | 166(8) |

| Educational attainment*** | |||

| Less than high school | 387 (9) | 177(16) | 520 (31) |

| High school graduate | 1,450 (28) | 436 (39) | 404 (27) |

| Some college | 1,451 (27) | 336 (26) | 341 (25) |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | 2,401 (36) | 288 (19) | 284(19) |

| Employment status*** | |||

| Employed | 4,121 (73) | 776 (67) | 1,192 (79) |

| Unemployed | 165 (3) | 90(11) | 89 (6) |

| Out of the labor force | 1,403 (23) | 371 (23) | 268 (15) |

| Relationship status*** | |||

| Married/cohabitating | 3,782 (71) | 576 (47) | 946 (61) |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 901(11) | 288 (17) | 228 (12) |

| Never married | 1,006 (18) | 373 (36) | 375 (28) |

| Past-year drinking status*** | |||

| Current drinker | 4,171 (73) | 697 (56) | 1,004 (65) |

| Former drinker | 770 (13) | 252(17) | 236(14) |

| Lifetime abstainer | 748 (14) | 288 (23) | 309(19) |

| Survey year*** | |||

| 2000 | 2,241 (38) | 497 (36) | 452 (26) |

| 2005 | 1,859 (31) | 369 (28) | 730 (43) |

| 2010 | 1,589 (31) | 371 (36) | 367 (31) |

Notes: Counts are unweighted; percentages are weighted.

Heterosexual self-identity and only female sex partners;

heterosexual self-identity and reporting male sex partners.

All between-group chi-squarep < .001.

Measures

NAS interviews collected self-reported sexual identity and sexual behavior, from which we created a three-category grouping variable. Men who identified as heterosexual and reported only female sex partners in the past 5 years were categorized as exclusively heterosexual (i.e., referent group). We constructed two sexual minority groups for comparisons: (a) men who self-identified as heterosexual and reported one or more male sex partners in the past 5 years (hereafter “behaviorally discordant heterosexual men”) and (b) men who self-identified as gay or bisexual, regardless of the gender of sex partners. Although some studies suggest poorer health profiles for bisexual men compared with gay men (Cochran et al., 2016; Conron et al., 2010), others have shown little difference in alcohol outcomes between these groups (Blosnich et al., 2014; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013; McCabe et al., 2013). For descriptive purposes, however, we disaggregated gay and bisexual men within racial/ethnic groups.

The analysis examined three alcohol outcomes. First, lifetime dependence symptoms were measured by a nine-item scale that assessed symptoms in seven domains corresponding to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Respondents who reported symptoms in three or more domains, such as unsuccessful attempts to quit or cut down drinking, withdrawal symptoms, and drinking in amounts larger than intended, were coded as positive for lifetime alcohol dependence (vs. fewer/no symptoms). Second, lifetime drinking-related consequences were measured by a 15-item scale of social consequences (4 items), health consequences (3 items), injuries and accidents (2 items), legal consequences (3 items), and workplace consequences (3 items) because of alcohol use. Consistent with previous NAS analyses of this variable (Greenfield et al., 2006; Zemore et al., 2013), respondents who endorsed two or more items were coded positive for lifetime drinking-related consequences (vs. one/no consequences). Third, paralleling a previous NAS analysis with sexual minorities (Drabble et al., 2016), we constructed an index of past-year hazardous drinking using four dichotomous indicators, including consuming five or more drinks on one occasion or more in the past year, drinking to intoxication two or more times in the past year, reporting one or more dependence symptoms in the past year, and reporting one or more alcohol-related consequences in the past year. Because drinking to intoxication was common, reported by 41% of drinkers, respondents who reported two or more of the four indicators were classified as positive for past-year hazardous drinking (vs. one/no indicators). In addition, we used count variables of lifetime dependence symptom domains (range: 0–7), lifetime drinking-related consequences (range: 0–15), and past-year hazardous drinking indicators (range: 0–4) for descriptive purposes. Additional covariates included survey year (2000 [referent], 2005, 2010) and four variables whose associations with alcohol use are well recognized: age (18–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years, 50–59 years, ≥60 years [referent]), educational attainment (less than high school diploma, high school diploma, some college, bachelor’s degree or higher [referent]), employment status (employed [referent], unemployed, out of the labor force), and relationship status (married/cohabitating [referent], formerly married, never married). The analytic sample used to estimate past-year hazardous drinking was restricted to the subset of current drinkers (n = 5,822); all other analyses used the full sample (n = 8,475), thereby producing generalizable population estimates of risk.

Analysis

We began by computing descriptive statistics by sexual orientation within racial/ethnic groups, using Rao–Scott chi-square tests of association for dichotomous variables and Poisson generalized linear models for count variables. Next, we tested potential demographic confounders of each outcome in bivariate tests of association. Following Hosmer and Lemeshow (2000), we set p < .25 as the criterion for inclusion in multivariable regression models. After assessing the main effects of sexual orientation and race/ethnicity on dichotomous outcomes, we entered interaction terms into logistic regression models to assess the presence of effect modification. Finally, we added the set of retained demographic covariates to produce fully adjusted models. To account for the parent study’s complex sampling design, all analyses used survey procedures (e.g., proc surveylogistic, in SAS Version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC), which adjusted estimates of standard errors. To better understand significant interactions in final models, we used the lsmeans and slice options to obtain conditional estimates for each combination of sexual orientation and race/ethnicity and then calculated odds ratios comparing sexual minorities to exclusively heterosexual men within each racial/ethnic group. Except for model building, the critical a for tests was .05.

Results

Sample characteristics

Exclusively heterosexual men constituted the majority (92%–96%) of each racial/ethnic group (Table 1). Among sexual minorities, larger percentages of Black men (4%) and Latino men (3%) were classified as behaviorally discordant heterosexuals compared with White men (2%). Gay-identified men represented the smallest sexual orientation group, with 1% of White and Latino men and 2% of Black men self-identifying as gay. Equivalent proportions (2%) of each group self-identified as bisexual. Although small, the proportions of gay and bisexual men were within ranges of other national estimates of sexual minorities (Gates, 2011). More White men were in older age strata and more Black and Latino men in the youngest age stratum. A larger proportion of White men reported a bachelor’s degree or higher than Black or Latino men. The majority of each racial/ethnic group was employed. Majorities of White and Latino men were married or cohabitating with a partner, but less than half of Black men were married or cohabitating. Drinking status varied by race/ethnicity, such that 73% of White men were current drinkers compared with 56% of Black and 65% of Latino men. In addition, 23% of Black and 19% of Latino men were lifetime abstainers, whereas 14% of White men had never consumed alcohol.

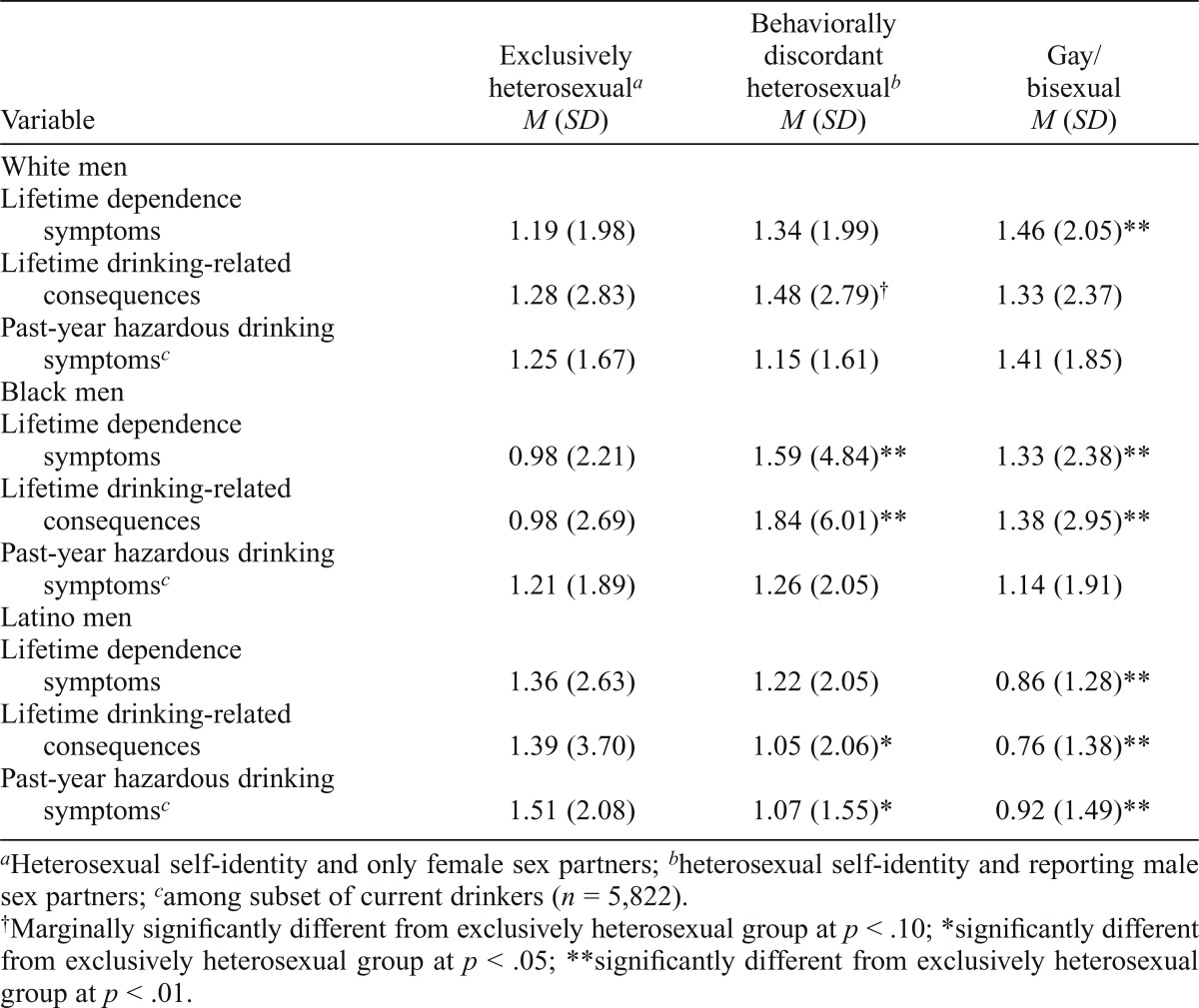

Alcohol problem symptom counts

Table 2 shows unadjusted counts of alcohol problem symptoms. Among White men, gay/bisexually identified men had higher mean lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms than exclusively heterosexual White men (1.46 vs. 1.19, p = .004), and behaviorally discordant heterosexual men had marginally higher mean lifetime drinking-related consequences than exclusively heterosexual White men (1.48 vs. 1.28, p = .06). Among Black men, gay/bisexually identified men and behaviorally discordant heterosexual men had higher mean lifetime dependence symptoms than same-race exclusively heterosexual peers (1.33 vs. 0.98, p < .001, and 1.59 vs. 0.98, p = .004, respectively) and higher mean lifetime drinking-related consequences than exclusively heterosexual Black men (1.38 vs. 0.98, p = .001, and 1.84 vs. 0.98, p < .001, respectively). In contrast, there were consistent differences in the opposite direction for gay/bisexually identified Latinos. Compared with exclusively heterosexual Latino men, gay/bisexual Latino men had lower mean lifetime dependence symptoms (1.36 vs. 0.86, p = .005), lower mean lifetime drinking-related consequences (1.39 vs. 0.76, p < .001), and lower mean past-year hazardous drinking index (1.51 vs. 0.92, p = .004). Similarly, behaviorally discordant heterosexual Latino men had lower mean lifetime drinking-related consequences and lower mean past-year hazardous drinking index than exclusively heterosexual Latino men (1.05 vs. 1.39, p = .03, and 1.07 vs. 1.51, p = .02, respectively).

Table 2.

Alcohol outcomes by sexual orientation within race/ethnicity among male respondents in three waves of the National Alcohol Survey (2000–2010)

| Variable | Exclusively heterosexuala M (SD) | Behaviorally discordant heterosexualb M (SD) | Gay/bisexual M (SD) |

| White men Lifetime dependence symptoms | 1.19 (1.98) | 1.34 (1.99) | 1.46 (2.05)** |

| Lifetime drinking-related consequences | 1.28 (2.83) | 1.48 (2.79)† | 1.33 (2.37) |

| Past-year hazardous drinking symptomsc | 1.25 (1.67) | 1.15 (1.61) | 1.41 (1.85) |

| Black men | |||

| Lifetime dependence symptoms | 0.98 (2.21) | 1.59 (4.84)** | 1.33 (2.38)** |

| Lifetime drinking-related consequences | 0.98 (2.69) | 1.84 (6.01)** | 1.38 (2.95)** |

| Past-year hazardous drinking symptomsc | 1.21 (1.89) | 1.26 (2.05) | 1.14 (1.91) |

| Latino men Lifetime dependence symptoms | 1.36 (2.63) | 1.22 (2.05) | 0.86 (1.28)** |

| Lifetime drinking-related consequences | 1.39 (3.70) | 1.05 (2.06)* | 0.76 (1.38)** |

| Past-year hazardous drinking symptomsc | 1.51 (2.08) | 1.07 (1.55)* | 0.92 (1.49)** |

Heterosexual self-identity and only female sex partners;

heterosexual self-identity and reporting male sex partners

among subset of current drinkers (n = 5,822).

Marginally significantly different from exclusively heterosexual group at p < .10;

significantly different from exclusively heterosexual group atp < .05;

significantly different from exclusively heterosexual group at p < .01.

Modeling risk of outcomes

All demographic characteristics met the inclusion criterion and were retained as covariates in our multivariable logistic regression models (Table 3). Because there was a significant race by sexual orientation interaction for lifetime dependence symptoms, we interpreted sexual orientation as conditional on racial/ethnic group. However, the race by sexual orientation interaction term was not significant for lifetime drinking-related consequences and past-year hazardous drinking. It was dropped from those models, allowing sexual orientation to be interpreted as a main effect independent of race/ethnicity.

Table 3.

Final logistic regression models of dichotomous alcohol outcomes among male respondents in three waves of the National Alcohol Survey (2000–2010)

| ≥3 lifetime dependence symptoms |

≥2 lifetime drinking-related consequences |

Past-year hazardous drinkinga |

|||||||

| Variable | b | SE | P | b | SE | P | b | SE | P |

| Sexual orientation | |||||||||

| Exclusively heterosexualb | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – |

| Behaviorally discordant heterosexualc | -0.384 | 0.292 | .19 | 0.160 | 0.207 | .44 | -0.227 | 0.229 | .32 |

| Gay/bisexual | 0.128 | 0.244 | .60 | 0.092 | 0.232 | .69 | -0.364 | 0.238 | .13 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – |

| Black | -0.309 | 0.136 | .02 | -0.488 | 0.112 | <.001 | -0.552 | 0.134 | <.001 |

| Latino | 0.092 | 0.115 | .43 | -0.225 | 0.101 | .03 | -0.275 | 0.113 | .02 |

| Interactions | |||||||||

| Black × Behaviorally Discordant Heterosexual | 1.580 | 0.596 | <.01 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Black × Gay/Bisexual | -0.099 | 0.622 | .87 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Latino × Behaviorally Discordant Heterosexual | 0.336 | 0.472 | .48 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Latino × Gay/Bisexual | -1.163 | 0.594 | .05 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Age | |||||||||

| 18–29 years | 0.877 | 0.168 | <.001 | 0.772 | 0.136 | <.001 | 2.817 | 0.175 | <.001 |

| 30–39 years | 1.062 | 0.165 | <.001 | 0.950 | 0.127 | <.001 | 2.145 | 0.165 | <.001 |

| 40–49 years | 0.951 | 0.158 | <.001 | 0.780 | 0.126 | <.001 | 1.504 | 0.162 | <.001 |

| 50–59 years | 0.817 | 0.151 | <.001 | 0.540 | 0.120 | <.001 | 0.970 | 0.164 | <.001 |

| >60 years | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – |

| Educational attainment | |||||||||

| Less than high school | 0.578 | 0.137 | <.001 | 0.603 | 0.119 | <.001 | 0.094 | 0.146 | .52 |

| High school graduate | 0.577 | 0.103 | <.001 | 0.512 | 0.084 | <.001 | 0.194 | 0.098 | .05 |

| Some college | 0.473 | 0.105 | <.001 | 0.415 | 0.087 | <.001 | 0.157 | 0.098 | .11 |

| Bachelor’s degree or more | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – |

| Employment status | |||||||||

| Employed | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – |

| Unemployed | 0.511 | 0.199 | .01 | 0.328 | 0.184 | .08 | 0.157 | 0.224 | .48 |

| Out of the labor force | 0.187 | 0.121 | .12 | 0.097 | 0.101 | .33 | -0.122 | 0.130 | .35 |

| Relationship status | |||||||||

| Married/cohabitating | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – |

| Separated/widowed/divorced | 0.387 | 0.117 | <.01 | 0.291 | 0.098 | <.01 | 0.350 | 0.117 | <.01 |

| Never married | -0.112 | 0.118 | .34 | –0.104 | 0.108 | .33 | 0.272 | 0.113 | .02 |

| Survey year | |||||||||

| 2000 | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – | ref. | – | – |

| 2005 | 0.431 | 0.087 | <.001 | 0.189 | 0.071 | <.01 | -0.015 | 0.082 | .85 |

| 2010 | 0.522 | 0.105 | <.001 | 0.4377 | 0.0853 | <.001 | 0.196 | 0.099 | .05 |

Notes: b = logit regression coefficient; ref. = reference.

Among subset of current drinkers (n = 5,822);

heterosexual self-identity and only female sex partners;

heterosexual self-identity and reporting male sex partners.

There was no difference in the risk of lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms among White men by sexual orientation. Similarly, there was no difference between gay/bisexual Black men and their same-race exclusively heterosexual peers; however, behaviorally discordant heterosexual Black men had three times higher odds of lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms than exclusively heterosexual Black men (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 3.30, 95% CI [1.19, 9.18], p = .02). Among Latino men, there was no difference in the risk of lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms between behaviorally discordant heterosexual and exclusively heterosexual groups. However, gay/bisexual Latino men had 64% lower odds of lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms than exclusively heterosexual Latino men (aOR = 0.36, 95% CI [0.12, 1.03], p = .06), although this effect was marginally significant.

There was no difference in the risk of lifetime drinking-related consequences by sexual orientation, independent of racial/ethnic group. However, there was a direct effect of race/ethnicity. Compared with White men, both Black and Latino men had lower odds of lifetime drinking-related consequences, regardless of sexual orientation (aOR = 0.61, 95% CI [0.49, 0.77], p < .001, and aOR = 0.80, 95% CI [0.66, 0.97], p = .03, respectively).

Similarly, among the subset of current drinkers (n = 5,822), there was no difference in the risk of past-year hazardous drinking by sexual orientation, independent of racial/ethnic group. There was a direct effect of race/ethnicity, such that Black men had 42% lower odds and Latino men had 24% lower odds of past-year hazardous drinking than White men (aOR = 0.58, 95% CI [0.44, 0.75], p < .001, and aOR = 0.76, 95% CI [0.61, 0.95], p = .02, respectively).

Discussion

Our hypothesis that sexual minority men would have equivalent or lower risk of hazardous drinking than heterosexual peers was largely supported. Multiple variable models of lifetime drinking-related consequences and past-year hazardous drinking showed no differences by sexual orientation. Examining lifetime dependence symptoms, however, gay/bisexual Latino men had marginally lower odds and behaviorally discordant Black men had higher odds of lifetime dependence symptoms than did their exclusively heterosexual same-race peers, respectively. Thus, broad statements of greater hazardous drinking and related consequences among sexual minority men appear unfounded. Further, the association between lifetime dependence symptoms and sexual orientation varies by race/ethnicity.

Stress-and-coping models, which are frequently used theoretical frameworks in alcohol research, may offer a potential explanation of these findings (Cappell & Greeley, 1987; Piazza & Le Moal, 1998). If behaviorally discordant heterosexual Black men experience increased stress because of discordant self-identity and sexual behavior, it may prompt greater alcohol use as a coping response, which in turn could increase lifetime risk of dependence. Because our study found that gay/bisexual Black men have an equivalent risk of lifetime alcohol dependence as exclusively heterosexual Black men, it is also possible that behaviorally discordant Black men fail to benefit from protective aspects of identity. Endorsement of a gay/bisexual identity may resolve sexual orientation-related stress, reducing the incentive to drink as a coping response. Further, there are indications of health benefits from participation in gay/bisexual communities, which may depend on adopting a gay/bisexual identity. For example, a study of sexual minority Latino men found that participation in LGBT or HIV-related community organizations attenuated associations between minority stigmas and risky sexual behavior, including reducing the likelihood of sex under the influence of alcohol and drugs (Ramirez-Valles et al., 2010). To our knowledge, the potential benefits of membership in gay/bisexual communities related to alcohol outcomes among Black men has yet to be studied.

There are several potential reasons that some Black men who have sex with men might not adopt a gay/bisexual identity. First, it may be racialized as a White identity (i.e., a label that only White men adopt). This may underlie the use of “same-gender loving,” which has emerged as an alternate, racially affirming identity among Black sexual minorities (Lassiter, 2014). Second, there may be perceptions of antigay prejudice within Black communities. Recent studies found that Black men who have sex with men feel considerable pressure to self-identify as heterosexual (Miller et al., 2005; Valera & Taylor, 2011), even adopting a heterosexual identity as a strategy to manage stigma and potential negative reactions (Schrimshaw et al., 2016). Third, it is possible that gay/bisexual and heterosexual are overly restrictive labels. Some research suggests the need for more nuanced sexual identity categories. For example, one study of college students found that approximately one third of respondents who had initially self-identified as bisexual chose “mostly heterosexual” or “mostly lesbian/gay” when given the opportunity (McCabe et al., 2012). The role of sexual self-identity among Black men, including alternate labels and changeable identities, warrants further study.

We found no indication that men who self-identify as gay/bisexual are at greater risk for alcohol problems. Indeed, findings for gay/bisexual Black and Latino men raise questions about the Double Jeopardy hypothesis (Dowd & Bengtson, 1978; Ferraro, 1987). Rather than increasing alcohol-related risk, one dimension of minority status may actually attenuate the effect of another. For example, Black and Latino men may benefit from protective effects associated with their minority race/ethnicity. It has been widely observed that greater proportions of Blacks and Latinos abstain from alcohol than their White counterparts, and that heavy drinking trajectories differ for racial/ethnic minority men (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; Dawson et al., 1995; Galvan & Caetano, 2003). There may be additional cultural factors associated with minority race/ethnicity, such as greater membership in religions that promote abstention (Daniel-Ulloa et al., 2014; Herd, 1994; Wallace et al., 2003), that constrain Black and Latino men’s alcohol use, regardless of sexual orientation. Among Latinos in particular, nativity may also be associated with decreased alcohol use, because foreign-born men appear to consume alcohol at lower levels and have fewer related problems than their U.S.-born counterparts (Szaflarski et al., 2011; Vega et al., 2004). Thus, a combination of sociocultural factors may act in concert to decrease the likelihood of heavy drinking among gay/bisexual men. Finally, there may be a uniquely protective ef fect of both minority statuses. Participation in Black or Latino gay/bisexual communities may provide affirmation of both minority race/ethnicity and minority sexuality, which in turn could reduce stress-reactive drinking or facilitate low-risk group norms for alcohol use. Additional research is needed to clarify the possible protective mechanisms associated with minority race/ethnicity and sexuality.

Although the present study failed to consistently replicate the previously observed race by sexual orientation interaction (Gilbert et al., 2015), we hesitate to dismiss the role of both factors. Although both studies used comparable nationally representative samples, the present study operationalized outcomes differently. Thus, comparability is limited. Nevertheless, findings are informative. Effect modification by race/ethnicity may be present only for certain alcohol outcomes, and additional work is needed to identify those relevant outcomes. Further, our previous study did not distinguish behaviorally discordant heterosexual men from gay and bisexually identified men. It is possible that race/ethnicity is salient only for some subgroups of sexual minority men. We look forward to future studies that clarify the instances where race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, both, or neither shape men’s alcohol-related risks.

Several potential limitations related to the composition of the sample should be taken into account. First, we restricted this study to White, Black, and Latino men, reducing generalizability of these findings to other racial/ethnic groups. Second, we used Latino as a homogeneous ethnic category, disregarding the great diversity in language, race or skin color, culture, and history across people with origins in Latin America. Third, we combined gay and bisexually identified men into a single category, thereby obscuring any potential differences between identity groups. Fourth, greater proportions of Black and Latino men were excluded because of missing sexual orientation data. If these men were also heavy drinkers, it could account for our findings of few differences. Although cognizant of these drawbacks, we proceeded with our study, believing that limited findings would nevertheless advance research on hazardous drinking among sexual minority men. With increasing adoption of multi-item sexual orientation measures in general population surveys, we look forward to future alcohol studies that take advantage of large samples and are able to further disaggregate racial/ethnic and sexual orientation categories. In particular, we note the need to explore potential differences by identity and behavior, both within and across racial/ethnic groups.

In summary, we found little support for broad statements of greater alcohol risk among gay/bisexual men. However, for lifetime dependence symptoms, the direction and degree of sexual minority men’s risk may depend on race/ethnicity. Specifically, behaviorally discordant heterosexual Black men had higher odds of lifetime alcohol dependence than exclusively heterosexual same-race peers. Additional research is needed to clarify men’s alcohol risk and protective factors related to race/ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rachael Korcha, Jamie Klinger, and Sarah Zemore for their assistance preparing the data set and George Pro for assistance with literature searches.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants P50AA005595 and T32AA007240, National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01DA036606, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Grant DP005021–01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blosnich J. R., Farmer G. W., Lee J. G., Silenzio V. M., Bowen D. J. Health inequalities among sexual minority adults: Evidence from ten U.S. states, 2010. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46:337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.010. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehmer U., Miao X., Linkletter C., Clark M. A. Adult health behaviors over the life course by sexual orientation. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:292–300. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300334. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappell H., Greeley J. Alcohol and tension reduction: An update on research and theory. In: Blane H. T., Leonard K. E., editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A., Mosher W. D., Copen C., Sionean C. Sexual behavior, sexual attraction, and sexual identity in the United States: Data from the 2006–2008 National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K., Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health. 2010;33:152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran S. D., Bjorkenstam C., Mays V M. Sexual orientation and all-cause mortality among US adults aged 18 to 59 years, 2001–2011. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106:918–920. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303052. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran S. D., Keenan C., Schober C, Mays V. M. Estimates of alcohol use and clinical treatment needs among homosexually active men and women in the U.S. population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1062–1071. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.6.1062. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.68.6.1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran S. D., Mays V. M., Alegria M., Ortega A. N., Takeuchi D. Mental health and substance use disorders among Latino and Asian American lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:785–794. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.785. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conron K. J., Mimiaga M. J., Landers S. J. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1953–1960. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.174169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel-Ulloa J., Reboussin B. A., Gilbert P. A., Mann L., Alonzo J., Downs M., Rhodes S. D. Predictors of heavy episodic drinking and weekly drunkenness among immigrant Latinos in North Carolina. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2014;8:339–348. doi: 10.1177/1557988313519670. doi:10.1177/1557988313519670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Grant B. F., Chou S. P., Pickering R. P. Subgroup variation in U.S. drinking patterns: Results of the 1992 national longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic study. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1995;7:331–344. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90026-8. doi:10.1016/0899-3289(95)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody S. S., Marshal M. P., Cheong J., Burton C., Hughes T., Aranda F, Friedman M. S. Longitudinal disparities of hazardous drinking between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:30–39. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd J. J., Bengtson V L. Aging in minority populations. An examination of the double jeopardy hypothesis. Journal of Gerontology. 1978;33:427–436. doi: 10.1093/geronj/33.3.427. doi:10.1093/geronj/33.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L., Midanik L. T., Trocki K. Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: Results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabble L., Trocki K. F., Klinger J. L. Religiosity as a protective factor for hazardous drinking and drug use among sexual minority and heterosexual women: Findings from the National Alcohol Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;161:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.022. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer G. W., Blosnich J. R., Jabson J. M., Matthews D. D. Gay acres: Sexual orientation differences in health indicators among rural and nonrural individuals. Journal of Rural Health. 2016;32:321–331. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12161. doi:10.1111/jrh.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K. F. Double jeopardy to health for black older adults? Journal of Gerontology. 1987;42:528–533. doi: 10.1093/geronj/42.5.528. doi:10.1093/geronj/42.5.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fifield L. H. On my way to nowhere: Alienated, isolated, and drunk. Los Angeles CA: Gay Community Services Center; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I., Kim H. J., Barkan S. E., Muraco A., Hoy-Ellis C. P. Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:1802–1809. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan F. H., Caetano R. Alcohol use and related problems among ethnic minorities in the United States. Alcohol Research & Health. 2003;27:87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. J. How many people are lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. Los Angeles CA: The Williams Institute, University of California Los Angeles; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gattis M. N., Sacco P., Cunningham-Williams R. M. Substance use and mental health disorders among heterosexual identified men and women who have same-sex partners or same-sex attraction: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41:1185–1197. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9910-1. doi:10.1007/s10508-012-9910-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P. A., Daniel-Ulloa J., Conron K. J. Does comparing alcohol use along a single dimension obscure within-group differences? Investigating men’s hazardous drinking by sexual orientation and race/ethnicity. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;151:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.010. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T. K., Nayak M. B., Bond J., Ye Y., Midanik L. T. Maximum quantity consumed and alcohol-related problems: Assessing the most alcohol drunk with two measures. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:1576–1582. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00189.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herd D. Predicting drinking problems among black and white men: Results from a national survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:61–71. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. doi:10.15288/jsa.1994.55.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer D., Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Igartua K., Thombs B. D., Burgos G., Montoro R. Concordance and discrepancy in sexual identity, attraction, and behavior among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.019. doi:10.1016/j. jadohealth.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski J. L., Ford J. A. Sexual orientation and alcohol use among college students: The influence of drinking motives and social norms. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2007;51:62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D. L., Ding K., Chaya J. Substance use of lesbian, gay, bisexual and heterosexual college students. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2014;38:951–962. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.38.6.17. doi:10.5993/AJHB.38.6.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassiter J. M. Extracting dirt from water: A strengths-based approach to religion for African American same-gender-loving men. Journal of Religion and Health. 2014;53:178–189. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9668-8. doi: 10.1007/s10943-012-9668-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohrenz L. J., Connelly J. C., Coyne L., Spare K. E. Alcohol problems in several midwestern homosexual communities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1978;39:1959–1963. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1978.39.1959. doi:10.15288/jsa.1978.39.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. E., Hughes T. L., Bostwick W., Boyd C. J. Assessment of difference in dimensions of sexual orientation: Implications for substance use research in a college-age population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:620–629. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.620. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. E., Hughes T. L., Bostwick W., Morales M., Boyd C. J. Measurement of sexual identity in surveys: Implications for substance abuse research. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41:649–657. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9768-7. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9768-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. E., Hughes T. L., Bostwick W. B., West B. T., Boyd C. J. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction. 2009;104:1333–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02596.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe S. E., West B. T., Hughes T. L., Boyd C. J. Sexual orientation and substance abuse treatment utilization in the United States: Results from a national survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;44:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.007. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M., Serner M., Wagner M. Sexual diversity among black men who have sex with men in an inner-city community. Journal of Urban Health, 82, Supplement. 2005;1:i26–i34. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti021. doi:10.1093/jurban/jti021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza P V, Le Moal M. Stress as a factor in addiction. In: Graham A. W., Schultz T. K., editors. Principles of addiction medicine. Chevy Chase, MD: American Society of Addition Medicine; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J., Kuhns L. M., Campbell R. T., Diaz R. M. Social integration and health: Community involvement, stigmatized identities, and sexual risk in Latino sexual minorities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:30–47. doi: 10.1177/0022146509361176. doi:10.1177/0022146509361176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. W., Essien E. J., Williams M. L., Fernandez-Esquer M. E. Concordance between sexual behavior and sexual identity in street outreach samples of four racial/ethnic groups. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30:110–113. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00003. doi:10.1097/00007435-200302000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghir M. T., Robins E. Male and female homosexuality: A comprehensive investigation. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw E. W., Downing M. J., Jr., Cohn D. J. Reasons for non-disclosure of sexual orientation among behaviorally bisexual men: Non-disclosure as stigma management. Archives of Sexual Behavior Advance online publication. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0762-y. doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0762-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexual Minority Assessment Research Team [SMART] Best practices for asking sexual orientation on surveys. Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski M., Cubbins L. A., Ying J. Epidemiology of alcohol abuse among US immigrant populations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2011;13:647–658. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9394-9. doi:10.1007/s10903-010-9394-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley A. E., Aranda F., Hughes T. L., Everett B., Johnson T. P. Longitudinal associations among discordant sexual orientation dimensions and hazardous drinking in a cohort of sexual minority women. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2015;56:225–245. doi: 10.1177/0022146515582099. doi:10.1177/0022146515582099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trocki K. F., Drabble L., Midanik L. Use of heavier drinking contexts among heterosexuals, homosexuals and bisexuals: Results from a National Household Probability Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:105–110. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.105. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valera P, Taylor T. Hating the sin but not the sinner: A study about heterosexism and religious experiences among black men. Journal of Black Studies. 2011;42:106–122. doi: 10.1177/0021934709356385. doi:10.1177/0021934709356385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega W. A., Sribney W. M., Aguilar-Gaxiola S., Kolody B. 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans: Nativity, social assimilation, and age determinants. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:532–541. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000135477.57357.b2. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000135477.57357.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. M., Jr., Brown T. N., Bachman J. G., LaVeist T. A. The influence of race and religion on abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:843–848. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.843. doi:10.15288/jsa.2003.64.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemore S. E., Karriker-Jaffe K. J., Mulia N. Temporal trends and changing racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol problems: Results from the 2000 to 2010 National Alcohol Surveys. Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy. 2013;4 doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000160. doi:10.4172/2155–6105.1000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]