Abstract

Objective:

Research on late-middle-aged and older adults has focused primarily on average level of alcohol consumption, overlooking variability in underlying drinking patterns. The purpose of the present study was to examine the independent contributions of an episodic heavy pattern of drinking versus a high average level of drinking as prospective predictors of drinking problems.

Method:

The sample comprised 1,107 adults ages 55–65 years at baseline. Alcohol consumption was assessed at baseline, and drinking problems were indexed across 20 years. We used prospective negative binomial regression analyses controlling for baseline drinking problems, as well as for demographic and health factors, to predict the number of drinking problems at each of four follow-up waves (1, 4, 10, and 20 years).

Results:

Across waves where the effects were significant, a high average level of drinking (coefficients of 1.56, 95% CI [1.24, 1.95]; 1.48, 95% CI [1.11, 1.98]; and 1.85, 95% CI [1.23, 2.79] at 1, 10, and 20 years) and an episodic heavy pattern of drinking (coefficients of 1.61, 95% CI [1.30, 1.99]; 1.61, 95% CI [1.28, 2.03]; and 1.43, 95% CI [1.08, 1.90] at 1, 4, and 10 years) each independently increased the number of drinking problems by more than 50%.

Conclusions:

Information based only on average consumption underestimates the risk of drinking problems among older adults. Both a high average level of drinking and an episodic heavy pattern of drinking pose prospective risks of later drinking problems among older adults.

Research on late-life adults has focused primarily on average level of alcohol consumption, overlooking variability in underlying drinking patterns. Yet, episodic heavy drinking is frequent among older adults (Blazer & Wu, 2009), and because of age-related elevations in comorbidities and medication use, this pattern of drinking may put many older drinkers at health risk (Barnes et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2013). Thus, researchers have been increasingly interested in understanding the psychosocial consequences of episodic heavy drinking in adult drinkers (Dawson et al., 2008; Wannamethee, 2013). The purpose of the present study was to extend this line of research by examining the independent contributions of an episodic heavy pattern of drinking versus a high average level of drinking as defined by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guidelines as prospective predictors of drinking problems in late-life adults.

Several studies have examined the role of drinking pattern in the negative consequences of alcohol use. Some of them have focused on alcohol use disorders as outcomes. For example, findings with more than 12,000 current drinkers age 18 years and older from three waves of the National Alcohol Survey demonstrated that both average level of alcohol use and pattern of consumption (frequency of consuming larger- than-usual daily quantities of alcohol) were significantly associated with risk for alcohol use disorders (Greenfield et al., 2014). However, the findings were cross-sectional, and the investigators noted that level and pattern of drinking as examined were not completely independent.

Using data on more than 40,000 U.S. drinkers age 18 years and older from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), Dawson et al. (2005) examined the prevalence of alcohol dependence with abuse in the context of NIAAA guidelines for average level (drinks per week) and pattern (drinks per day) of drinking. The prevalence of alcohol dependence with abuse increased linearly with frequency of exceeding guidelines for pattern of drinking. Alcohol dependence was more closely tied to exceeding guidelines for pattern than for average level of drinking. Again, however, the data were cross-sectional.

We have conducted prior research with the broader sample of older adults from which the present subsample was drawn, focusing on the role of drinking pattern in predicting drinking problems, defined as negative psychological and social consequences of alcohol use. For example, in crosssectional analyses at baseline and time-lagged analyses at 10 years with approximately 1,300 participants, the largest daily amount of alcohol (indexed as ounces of ethanol) significantly predicted drinking problems (Moos et al., 2004b). However, neither the pattern of drinking nor drinking guidelines was examined.

We also examined drinking problems in the context of alternative guidelines for alcohol use at baseline and 10 years (Moos et al., 2004a) and at 20 years (Moos et al., 2009). Alcohol consumption in excess of guidelines reflecting either average level (weekly consumption) or pattern (largest daily consumption) of drinking was associated with increased risk of drinking problems. These findings held even in the context of conservative guidelines. However, the analyses were cross-sectional and, although both average level and pattern of drinking were examined separately and in combination, their independent effects were not examined.

Dawson et al. (2008) conducted the only study we are aware of that examines drinking pattern and alcohol abuse and dependence in a prospective design. The investigators used 3-year prospective data on more than 20,000 U.S. adult drinkers age 18 years and older across two waves of the NESARC. The odds of alcohol abuse and dependence increased steadily with increasing frequency of exceeding NIAAA guidelines for pattern (drinks per day) of drinking. However, the study did not focus on older drinkers and did not examine the independent effects of both level and pattern of drinking. The investigators also acknowledged that the 3-year follow-up might not have reflected longer term processes.

Present study

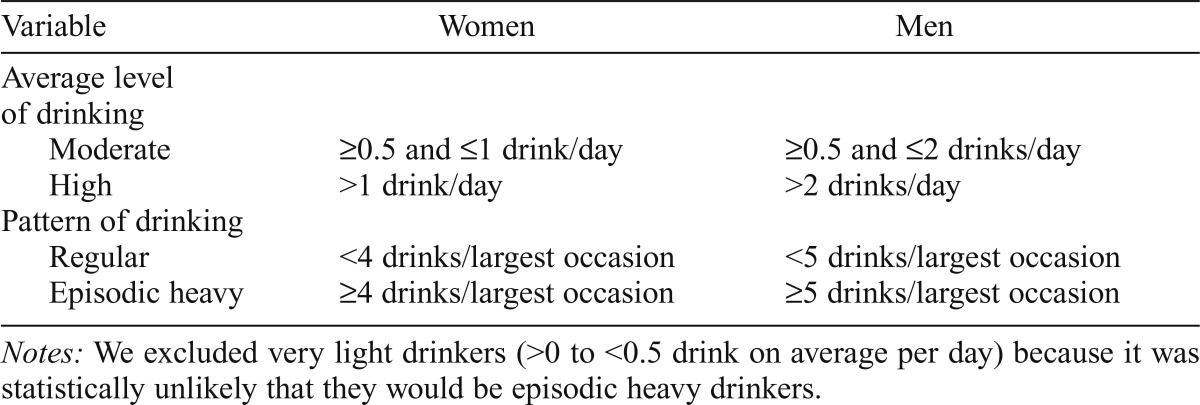

The present study examined the independent contributions of an episodic heavy pattern of drinking versus a high average level of drinking as prospective predictors of drinking problems across a 20-year follow-up period among 1,107 late-middle-aged and older adults. To enhance the public health and clinical applicability of our findings, we applied NIAAA guidelines of moderate versus high average level of drinking and of regular versus episodic heavy drinking (Gunzerath et al., 2004; NIAAA, 2007) (Table 1). The study extends previous research on the role of drinking pattern in alcohol use disorders among adults age 18 years and older (Dawson et al., 2005, 2008; Greenfield et al., 2014) and in drinking problems among older adults (Moos et al., 2004a, 2004b, 2009). Analyses examine the independent effects of drinking level and drinking pattern. We use a prospective predictive framework, covering two decades from an average of age 60-80 years.

Table 1.

Definitions of the alcohol consumption groups

| Variable | Women | Men |

| Average level of drinking | ||

| Moderate | ≥0.5 and ≤1 drink/day | ≥0.5 and ≤2 drinks/day |

| High | >1 drink/day | >2 drinks/day |

| Pattern of drinking | ||

| Regular | <4 drinks/largest occasion | <5 drinks/largest occasion |

| Episodic heavy | ≥4 drinks/largest occasion | ≥5 drinks/largest occasion |

Notes: We excluded very light drinkers (>0 to <0.5 drink on average per day) because it was statistically unlikely that they would be episodic heavy drinkers.

Method

Sample selection and characteristics

The present study is part of an overall longitudinal project that has examined late-life patterns of alcohol consumption and drinking problems (Brennan et al., 2010, 2011a; Moos et al., 2004b, 2009, 2010; Schutte et al., 2006) among late-middle-aged and older adults. A key goal of the overall project was to select individuals with a wide range of drinking behaviors, including current or past drinking problems. Based on information from two medical centers in the western United States, we contacted individuals between ages 55 and 65 years who had had outpatient contact with one or both of the medical centers in the previous 3 years. The sample was comparable to similarly aged community samples with respect to health characteristics such as prevalence of arthritis, hypertension, and diabetes, and self-reported occurrence and length of hospitalization (Brennan & Moos, 1990; Moos et al., 1991).

Data were collected by individual surveys sent directly to participants at baseline and at 1, 4, 10, and 20 years. Of eligible respondents contacted at baseline, 92% agreed to participate, and 89% (1,884) of these individuals provided complete data at baseline. Among participants who were still living (and for the 20-year follow-up not in very poor health), follow-up rates at these waves were 94%, 94%, 93%, and 86%, respectively (Moos et al., 2009). The study was approved by the Stanford University Medical School Panel on Human Subjects; after the project was fully explained, participants provided signed informed consent.

The present study included 1,107 baseline participants from the overall project who met the alcohol consumption criteria described below and who participated at baseline and in at least one follow-up. The sample included 400 (36%) women and 707 (64%) men. At baseline, participants were an average of 61 (SD = 3.12) years of age, and 74% were married. Participants had an average of 14.5 (SD = 2.30) years of education and were predominantly White (93%).

Measures

Alcohol consumption and the set of covariates were measured at baseline; drinking problems were measured at baseline and at four follow-ups (1, 4, 10, and 20 years). Descriptive and psychometric information on the measures is available in the Health and Daily Living Form (Moos et al., 1992) for the measures of alcohol consumption and demographic and health factors, and in the Drinking Problems Index (Finney et al., 1991) for the measure of drinking problems. Following Holahan et al. (2014, 2015), we applied NIAAA guidelines in defining both level and pattern of drinking.

Alcohol consumption groups

Average level of drinking was measured by items in a quantity-frequency index of typical drinking, and pattern of drinking was measured by items tapping the largest amount participants drank. The definitions of alcohol consumption groups are described below.

Average level of drinking (moderate vs. high).

Average level of drinking was assessed at baseline with a quantity- frequency index. Respondents were asked, “During the last month, how much of each of the following beverages did you usually drink in a typical day when you drank that beverage?” Quantity of alcohol consumption was assessed by items that measured the amounts of wine, beer, and distilled spirits participants had consumed on the days they drank in the last month. Responses to these items were converted to reflect the ethanol content of the beverages consumed. Frequency of alcohol consumption was assessed by responses to questions asking how often per week (never, less than once, once or twice, three to four times, nearly every day) participants had consumed wine, beer, or distilled spirits in the last month. From this information, quantity-frequency values were calculated to provide indices of participants’ average daily ethanol consumption of each beverage type. Summing average daily ethanol consumption from the three beverage types provided a composite index of participants’ average daily level of drinking.

Using the measure of average daily level of drinking, number of drinks per day was indexed based on the approximation that 5 oz of wine, 12 oz of beer, and 1 shot (1.5 oz) of distilled spirits contain an average of 0.6 oz of ethanol (NIAAA, 2007). Applying NIAAA guidelines (Gunzerath et al., 2004; NIAAA, 2007), moderate drinking (score = 0) was defined as an average daily level of drinking that was at least one-half drink per day but no more than 1 drink per day for women and 2 drinks per day for men. Correspondingly, high drinking (score = 1) was defined as an average daily level of drinking that was greater than one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men. Following Holahan et al. (2014, 2015), very light drinkers (>0 to <half of a drink on average per day) were excluded because it was statistically unlikely that they would be episodic heavy drinkers.

Pattern of drinking (regular vs. episodic heavy).

Next, we identified pattern of drinking at baseline through responses to a separate set of additional items that asked separately about wine, beer, and distilled spirits, as follows: “During the last month what was the largest amount you drank of each of the following beverages?” Response options were indexed in number of glasses of wine, cans of beer, and shots of distilled spirits. Episodic heavy drinking was defined consistent with NIAAA guidelines (Gunzerath et al., 2004; NIAAA, 2007) and in a manner identical to that used in the NESARC and the U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (Chavez et al., 2011). Regular drinking (score = 0) was defined as consuming fewer than 4 (for women) and fewer than 5 (for men) drinks on the occasion of the largest amount of drinking. Episodic heavy drinking (score = 1) was defined as consuming 4 or more (for women) and 5 or more (for men) drinks on the occasion of the largest amount of drinking.

Drinking problems.

An index of drinking problems in the last 12 months was composed of 12 items drawn from the Drinking Problems Index (Finney et al., 1991), which has high internal consistency (α = .94) and good construct and predictive validity (Bamberger et al., 2006; Finney et al., 1991; Kopera-Frye et al., 1999). The total drinking problems score at each wave ranges from 0 to 12. The 12 items indicate functioning problems due to drinking (i.e., becoming drunk; having falls/accidents; spending too much money on alcohol; skipping meals; and neglecting personal appearance, living quarters, or work) and interpersonal problems due to drinking (i.e., having a family member or friend worry or complain about one’s drinking, family problems, losing friends, and feeling isolated). The 12-item version of the Drinking Problems Index has high internal consistency (α = .92; average corrected item-total score correlations = .71 with a range from .58 to .78) and is highly correlated with the original 17-item Drinking Problems Index (r = .91) (Moos et al., 2009). In addition, the 12-item version is predictably associated with a history of heavy drinking and drinking problems, trying to cut down on and seeking help for drinking, friends’ approval of drinking, smoking, use of psychoactive medications, and reliance on avoidance coping (Moos et al., 2004b, 2005).

Covariates.

Based on Moos et al. (2004b), we controlled at baseline for age, gender (female = 0, male = 1), and marital status (not married = 0, married = 1). We also controlledfor socioeconomic status. Following Holahan et al. (2010), we indexed socioeconomic status as the average of participant’s family income and years of education, using standard scores for both measures to equate their scales. In 42 cases in which family income was not available, we used years of education alone. In addition, we controlled for medical conditions based on evidence that they are associated with drinking problems (Brennan et al., 2011b; Ryan et al., 2013). Medical conditions were a count of nine conditions diagnosed by a physician and experienced in the past 12 months (cancer, diabetes, heart problems, stroke, high blood pressure, anemia, bronchitis, kidney problems, and ulcers).

Results

Background information

The prevalence of a high average level of drinking was 60% at baseline, and the prevalence of episodic heavy drinking at baseline was 41%. The prevalence of any drinking problems at baseline and at 1, 4, 10, and 20 years was 48%, 43%, 39%, 30%, and 20%, respectively. Among participants with any drinking problems, the mean number of drinking problems at baseline and at 1, 4, 10, and 20 years was 3.11 (SD = 2.42), 3.27 (SD = 2.52), 2.96 (SD = 2.38), 2.75 (SD = 2.21), and 2.37 (SD = 1.88), respectively. The correlation between average level and pattern of drinking at baseline was .40, reflecting 16% of shared variance.

Drinking problems at follow-up

After initial model testing, we conducted negative binomial regression analyses to examine the roles of average level versus pattern of drinking in prospectively predicting the number of drinking problems. Specifically, the analyses tested the independent effects of a high average level of drinking and an episodic heavy pattern of drinking at baseline, controlling for one another, in predicting the number of drinking problems at each of the four follow-up waves (1, 4, 10, and 20 years). All analyses were prospective, controlling for drinking problems at baseline. Thus, the analyses tested a departure from the expected number of drinking problems at each follow-up based on previous drinking problems at baseline. In addition, all models controlled for age, sex, socioeconomic status, marital status, and medical conditions.

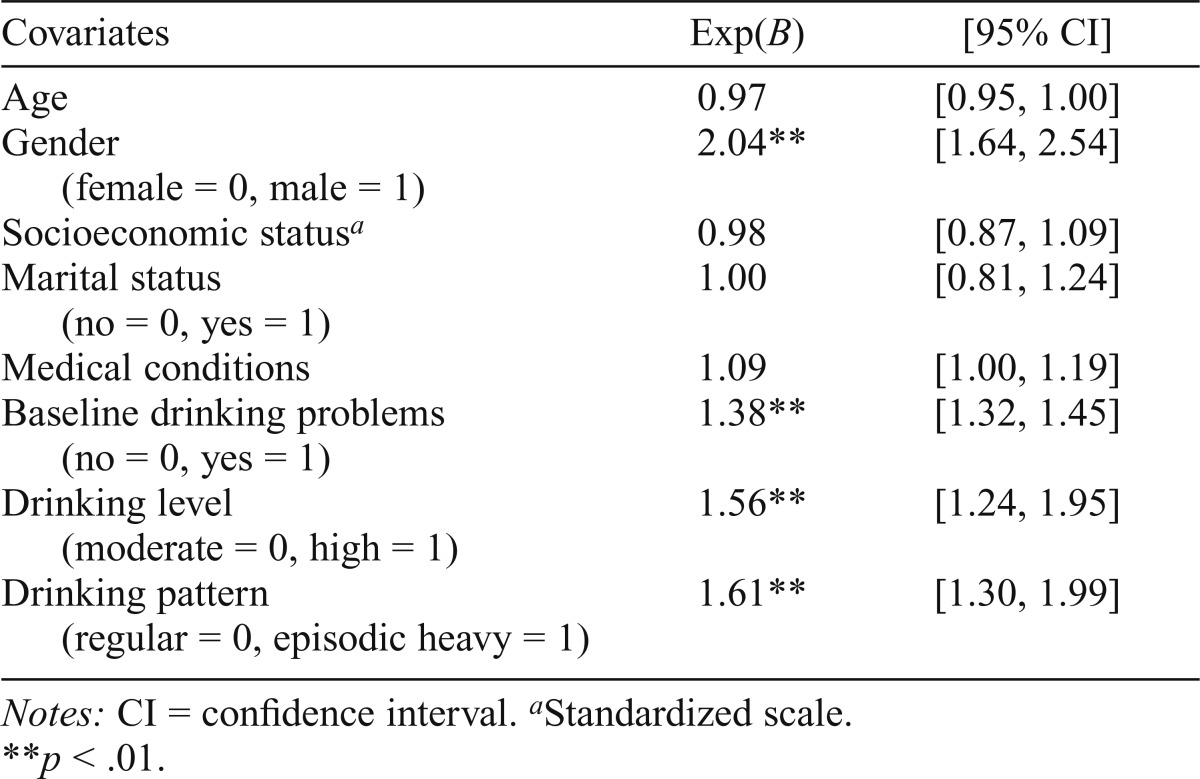

Table 2 shows exponentiated coefficients, significance levels, and 95% confidence intervals from the negative binomial regression analysis with drinking level and drinking pattern at baseline prospectively predicting drinking problems at the 1-year follow-up. Table 3 shows exponentiated coefficients, significance levels, and 95% confidence intervals from the negative binomial regression analyses with drinking level and drinking pattern at baseline prospectively predicting drinking problems at each of the subsequent follow-up waves (i.e., 4, 10, and 20 years). The coefficients for covariates at 4, 10, and 20 years were very similar to those at 1 year reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of a negative binomial regression analysis with drinking level and drinking pattern at baseline prospectively predicting the number of drinking problems at the 1-year follow-up (N = 1,063)

| Covariates | Exp(B) | [95% CI] |

| Age | 0.97 | [0.95, 1.00] |

| Gender | 2.04** | [1.64, 2.54] |

| (female = 0, male = 1) | ||

| Socioeconomic statusa | 0.98 | [0.87, 1.09] |

| Marital status | 1.00 | [0.81, 1.24] |

| (no = 0, yes = 1) | ||

| Medical conditions | 1.09 | [1.00, 1.19] |

| Baseline drinking problems | 1.38** | [1.32, 1.45] |

| (no = 0, yes = 1) | ||

| Drinking level | 1.56** | [1.24, 1.95] |

| (moderate = 0, high = 1) | ||

| Drinking pattern | 1.61** | [1.30, 1.99] |

| (regular = 0, episodic heavy = 1) |

Notes: CI = confidence interval.

Standardized scale.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Results of negative binomial regression analyses with drinking level and drinking pattern at baseline prospectively predicting the number of drinking problems at the 4-, 10-, and 20-year follow-ups

| Baseline drinking levela |

Baseline drinking patternb |

||||||

| Outcome | n | Exp(B) | [95% CI] | P | Exp(B) | [95% CI] | P |

| Drinking problems at 4 years | 989 | 1.23 | [0.97, 1.57] | .09 | 1.61 | [1.28, 2.03] | <.01 |

| Drinking problems at 10 years | 767 | 1.48 | [1.11, 1.98] | <.01 | 1.43 | [1.08, 1.90] | <.05 |

| Drinking problems at 20 years | 494 | 1.85 | [1.23, 2.79] | <.01 | 1.08 | [0.71, 1.63] | .73 |

Notes: All analyses controlled for drinking problems at baseline as well as for age, sex, socioeconomic status, marital status, and medical conditions. CI = confidence interval.

Moderate = 0, high = 1;

regular = 0, episodic heavy = 1.

Overall, both a high average level of drinking and an episodic heavy pattern of drinking at baseline prospectively and independently predicted the number of drinking problems across the follow-up period. Across the three waves where the effect for average level of drinking was significant (1, 10, and 20 years), a high compared to a moderate average level of drinking was independently associated on average with a 63% increase in the number of drinking problems. Across the three waves where the effect for pattern of drinking was significant (1, 4, and 10 years), an episodic heavy pattern of drinking compared to a regular pattern of drinking was independently associated on average with a 55% increase in the number of drinking problems.

We also examined possible gender interactions in each model. The interaction of gender with baseline pattern of drinking was not significant in predicting drinking problems at any of the follow-up waves (p > .05). However, the interaction of gender with baseline level of drinking was significant in predicting drinking problems at the 1-, 4-, and 10-year follow-ups (p < .05), with the independent effect for high-level drinking slightly stronger for women than for men. The interaction of gender with baseline level of drinking was not significant in predicting drinking problems at the 20-year follow-up (p > .05).

We re-examined the independent contribution of pattern of drinking in the 1-, 4-, and 10-year models, retaining the interaction of gender with baseline level of drinking in the models. Pattern of drinking continued to make a significant independent contribution in prospectively predicting drinking problems at the 1-, 4-, and 10-year follow-ups. The parameter estimates and significance levels for an episodic heavy pattern of drinking compared with a regular pattern of drinking were nearly identical to those reported in Tables 2 and 3 at 1 year, Exp(B) = 1.62, p < .01, and at 4 years, Exp(B) = 1.61, p < .01. The parameter estimates and significance levels for an episodic heavy pattern of drinking compared with a regular pattern of drinking were slightly stronger than those reported in Table 3 at 10 years, Exp(B) = 1.45, p < .01.

Discussion

Building on previous research on the role of drinking pattern in alcohol use disorders among mixed-age adults (Dawson et al., 2005, 2008; Greenfield et al., 2014) and in drinking problems among older adults (Moos et al., 2004a, 2004b, 2009), the present findings demonstrate that both a high average level of drinking and an episodic heavy pattern of drinking pose prospective risks of later drinking problems among older adults. Across waves where the effects were significant, a high average level of drinking and an episodic heavy pattern of drinking each independently increased the number of drinking problems by more than 50%. These findings control for baseline drinking problems and provide a conservative test of the long-term predictive roles of average level and pattern of drinking.

Because they can be easily communicated and understood, threshold-based drinking guidelines play an important role in framing public health messages and in identifying risky drinking in clinical contexts (Dawson, 2011; Falk et al., 2010). However, low-risk drinking guidelines historically have been based more on experts’ judgment than on research data (Greenfield et al., 2014). In conjunction with our recent work on the significant role of both high-level drinking and episodic heavy drinking in mortality (Holahan et al., 2014, 2015), these findings provide empirical support for current NIAAA guidelines for older adults (Gunzerath et al., 2004; NIAAA, 2007). Low-risk drinking requires avoiding both high average consumption and an episodic heavy drinking pattern. Our findings pertaining to pattern of drinking are also consistent with the current U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) definition of successful alcohol clinical trials in terms of the percentage of participants who refrain from heavy drinking (indexed as four or more drinks for women and five or more drinks for men) (Falk et al., 2010).

Some limitations should be kept in mind when interpreting the present findings. Our findings and those of the earlier studies we cite are correlational and do not provide evidence of causality. In addition, because our study and the studies we cite often used different measures of drinking behavior, comparisons across studies should be made cautiously. There is a need for integrative approaches to operationalizing drinking behavior to facilitate relating different drinking measures to one another (see Gruenewald et al., 2016). Also, our measures of alcohol consumption were based on selfreport. Future research would be strengthened by including objective indices or collateral information on patterns of alcohol use. In addition, because we selected respondents from a distinct geographical region who had sought health care and excluded lifelong abstainers and very infrequent drinkers, the sample is not representative of the U.S. population of older adults.

Further, although categorical drinking guidelines have public health and clinical applicability, continuous predictors of drinking behavior are likely to provide increased statistical power and can uncover nonlinear components in the relationship of drinking behavior to drinking problems (Gruenewald et al., 2016; Pearson et al., 2016a, 2016b). Even in a clinical context, categorical drinking guidelines should not be applied inflexibly. For example, Wilson et al. (2016) found heterogeneity in the psychosocial functioning of individuals who did not do well in treatment based on the FDA binary criterion for treatment success, with some individuals who were classified as “treatment failures” reporting psychosocial functioning comparable to those classified as “treatment successes.”

Past research on alcohol and mortality among older adults has emphasized average level of alcohol consumption, overlooking the importance of drinking pattern (Naimi et al., 2013; Wannamethee, 2013). Information based only on average consumption underestimates the risk for drinking problems among older drinkers (Dawson et al., 2008; Wan- namethee, 2013). Along with our earlier findings (Holahan et al., 2014, 2015), the results of this investigation highlight the importance of drinking pattern, in addition to average level of drinking, in predicting adverse outcomes in late life. Evidence of the risk for drinking problems as a function of pattern as well as average level of drinking can inform the focus of educational and intervention efforts with late-middle-aged and older adults (Ettner et al., 2014). Key components in interventions to reduce at-risk drinking among older adults include discussing alcohol risk with a physician, making a drinking agreement with a health educator, and keeping a drinking diary (Dura et al., 2015). Each of these approaches provides an ideal opportunity for focusing on pattern as well as average level of alcohol consumption.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bernice Moos for her contribution in setting up and developing the data files used in this investigation.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant AA15685 and by Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service funds. The opinions expressed here are the authors’ and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- Bamberger P. A., Sonnenstuhl W. J., Vashdi D. Screening older, blue-collar workers for drinking problems: An assessment of the efficacy of the drinking problems index. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2006;11:119–134. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.119. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.11.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes A. J., Moore A. A., Xu H., Ang A., Tallen L., Mirkin M., Ettner S. L. Prevalence and correlates of at-risk drinking among older adults: The Project SHARE study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25:840–846. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1341-x. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1341-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D. G., Wu L. T. The epidemiology of at-risk and binge drinking among middle-aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:1162–1169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010016. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. L., Moos R. H. Life stressors, social resources, and late-life problem drinking. Psychology and Aging. 1990;5:491–501. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.5.4.491. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.5.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., Moos B. S., Moos R. H. Twenty-year alcohol-consumption and drinking-problem trajectories of older men and women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011a;72:308–321. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.308. doi:10.15288/jsad.2011.72.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., Moos R. H. Patterns and predictors of late-life drinking trajectories: A 10-year longitudinal study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:254–264. doi: 10.1037/a0018592. doi:10.1037/a0018592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., SooHoo S., Moos R. H. Painful medical conditions and alcohol use: A prospective study among older adults. Pain Medicine. 2011b;12:1049–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01156.x. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011. 01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez P. R., Nelson D. E., Naimi T. S., Brewer R. D. Impact of a new gender-specific definition for binge drinking on prevalence estimates for women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;40:468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A. Defining risk drinking. Alcohol Research & Health. 2011;34:144–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Grant B. F., Li T.-K. Quantifying the risks associated with exceeding recommended drinking limits. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:902–908. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164544.45746.a7. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000164544.45746.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Li T.-K., Grant B. F. A prospective study of risk drinking: At risk for what? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.00. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duru O. K., Xu H., Moore A. A., Mirkin M., Ang A., Tallen L., Ettner S. L. Examining the impact of separate components of a multicomponent intervention designed to reduce at-risk drinking among older adults: The Project SHARE Study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:1227–1235. doi: 10.1111/acer.12754. doi:10.1111/acer.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner S. L., Xu H., Duru O. K., Ang A., Tseng C.-H., Tallen L., Moore A. A. The effect of an educational intervention on alcohol consumption, at-risk drinking, and health care utilization in older adults: The Project SHARE study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:447–457. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.447. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D., Wang X. Q., Liu L., Fertig J., Mattson M., Ryan M., Litten R. Z. Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: Evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcohol clinical trials. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:2022–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01290.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney J. W., Moos R. H., Brennan P. L. The Drinking Problems Index: A measure to assess alcohol-related problems among older adults. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1991;3:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(10)80021-5. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(10)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T. K., Ye Y., Bond J., Kerr W. C., Nayak M. B., Kaskutas L. A., Kranzler H. R. Risks of alcohol use disorders related to drinking patterns in the U.S. general population. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:319–327. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.319. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald P. J., Wang-Schweig M., Mair C. Sources of misspecification bias in assessments of risks related to alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77:802–810. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.802. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunzerath L., Faden V., Zakhari S., Warren K. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:829–847. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128382.79375.b6. doi:10.1097/01.ALC.0000128382.79375.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. J., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Holahan C. K., Moos B. S., Moos R. H. Late-life alcohol consumption and 20-year mortality. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1961–1971. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01286.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. J., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Holahan C. K., Moos R. H. Episodic heavy drinking and 20-year total mortality among late-life moderate drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:1432–1438. doi: 10.1111/acer.12381. doi:10.1111/acer.12381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. J., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Holahan C. K., Moos R. H. Drinking level, drinking pattern, and twenty-year total mortality among late-life drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;67:552–558. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.552. doi:10.15288/jsad.2015.76.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopera-Frye K., Wiscott R., Sterns H. L. Can the Drinking Problem Index provide valuable therapeutic information for recovering alcoholic adults? Aging & Mental Health. 1999;3:246–256. doi:10.1080/13607869956217. [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Brennan P. L., Moos B. S. Short-term processes of remission and nonremission among late-life problem drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1991;15:948–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., Moos B. S. High- risk alcohol consumption and late-life alcohol use problems. American Journal of Public Health. 2004a;94:1985–1991. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.11.1985. doi:10.2105/AJPH.94.11.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Brennan P. L., Schutte K. K., Moos B. S. Older adults’ health and changes in late-life drinking patterns. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9:49–59. doi: 10.1080/13607860412331323818. doi:10.1080/13607860412331323818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Cronkite R. C., Finney J. W. 2nd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1992. Health and Daily Living Form Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Schutte K., Brennan P., Moos B. S. Ten- year patterns of alcohol consumption and drinking problems among older women and men. Addiction. 2004b;99:829–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00760.x. doi:10.1111/j. 1360-0443.2004.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Moos B. S. Older adults alcohol consumption and late-life drinking problems: A 20-year perspective. Addiction. 2009;104:1293–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02604.x. doi:10. 1111 /j. 1360-0443.2009.02604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R. H., Schutte K. K., Brennan P. L., Moos B. S. Late-life and life history predictors of older adults’ high-risk alcohol consumption and drinking problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;108:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi T. S., Xuan Z., Brown D. W., Saitz R. Confounding and studies of moderate alcohol consumption: The case of drinking frequency and implications for low-risk drinking guidelines. Addiction. 2013;108:1534–1543. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04074.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIH Publication No. 07–3769; 2007. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide (updated) Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M. R., Kirouac M., Witkiewitz K. Questioning the validity of the 4+/5+ binge or heavy drinking criterion in college and clinical populations. Addiction. 2016a;111:1720–1726. doi: 10.1111/add.13210. doi:10.1111/add.13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson M. R., Kirouac M., Witkiewitz K. We still question the utility and validity of the binge/heavy drinking criterion. Addiction. 2016b;111:1733–1734. doi: 10.1111/add.13384. doi:10.1111/add.13384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M., Merrick E. L., Hodgkin D., Horgan C. M., Garnick D. W., Panas L., Saitz R. Drinking patterns of older adults with chronic medical conditions. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28:1326–1332. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2409-1. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2409-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte K. K., Moos R. H., Brennan P. L. Predictors of untreated remission from late-life drinking problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:354–362. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.354. doi:10.15288/jsa.2006.67.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wannamethee S. G. Significance of frequency patterns in ‘moderate’ drinkers for low-risk drinking guidelines [Commentary] Addiction. 2013;108:1545–1547. doi: 10.1111/add.12089. doi:10.1111/add.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A. D., Bravo A. J., Pearson M. R., Witkiewitz K. Finding success in failure: Using latent profile analysis to examine heterogeneity in psychosocial functioning among heavy drinkers following treatment. Addiction. 2016;111:2145–2154. doi: 10.1111/add.13518. doi:10.1111/add.13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S. R., Knowles S. B., Huang Q., Fink A. The prevalence of harmful and hazardous alcohol consumption in older U.S. adults: Data from the 2005-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;29:312–319. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2577-z. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2577-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]