Abstract

Objective:

The unique influence of fathers’ alcohol and cannabis use disorder on children’s onset of use of these same substances has been rarely studied. A clear understanding of family history in this context is important for the development of family-based prevention initiatives aimed at delaying the onset of substance use among children.

Method:

Prospective, longitudinal, and intergenerational data on 274 father–child dyads were used. Logistic regression models were estimated to assess the association between fathers’ lifetime incidence of an alcohol and cannabis use disorder and children’s onset of use of these same substances at or before age 15.

Results:

The children of fathers who met the criteria for a lifetime cannabis use disorder were more likely to initiate use of alcohol (odds ratio = 6.71, 95% CI [1.92, 23.52]) and cannabis (odds ratio = 8.13, 95% CI [2.07, 31.95]) by age 15, when background covariates and presence of a lifetime alcohol use disorder were controlled for. No unique effect of fathers’ alcohol use disorder on children’s onset of alcohol and cannabis use was observed.

Conclusions:

Fathers’ lifetime cannabis use disorder had a unique and robust association with children’s uptake of alcohol and cannabis by age 15. Future research is needed to identify the mediating mechanisms that link fathers’ disorder with children’s early onset.

Substance use disorders are far too common in the United States and present a major public health concern. Recent estimates from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III show that 36.0% of adult men report a lifetime alcohol use disorder (Grant et al., 2015) and 8.4% report a lifetime cannabis use disorder (Hasin et al., 2016). Individuals who experience these disorders are more likely to experience a host of undesirable outcomes, including compromised mental and physical health (Rehm et al., 2014; Volkow et al., 2016). In addition to these personal harms, a parent’s substance use disorder can have negative implications for his or her child.

The negative influence of a parental alcohol use disorder on a child’s early initiation and escalation of substance use is well documented in the literature (Chassin et al., 1996, 2004; Hussong et al., 2012). However, comparatively little work has examined interfamilial continuity in substance use for cannabis (Bailey et al., 2016). Moreover, although there is evidence of the co-occurrence of alcohol and cannabis use disorders, particularly among males (Stinson et al., 2005), the unique influence of parental alcohol and cannabis use disorders on children’s uptake of these same substances is not well understood (Capaldi et al., 2016). Capaldi and colleagues examined the role of fathers’ use of alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis on children’s onset of alcohol use. None of the substances examined by the authors had a main effect in predicting children’s age at alcohol onset; however, an interactive effect of fathers’ alcohol and cannabis use was observed. The combined use of both substances by a father increased the likelihood that his child would use. More work to examine these effects in other samples is needed, as a clear understanding of family history in this context is important for the development of family-based prevention initiatives aimed at delaying onset of substance use among children.

Much of the theory building and testing surrounding parents’ use of substances on children’s initiation of substance use has specifically focused on parental alcoholism. Hussong and colleagues (2012) reported that the distal effect of a parental lifetime alcohol use disorder on adolescents’ use of substances was positive and significant, whereas the proximal effects of current parental alcohol abuse did not further increase the risk of substance use among adolescents. The authors argue that the salience of this distal effect may be indicative of genetic vulnerability and/or an early emerging pathway of risk in which prior abuse of alcohol by a parent leads to internalizing and externalizing problems during early childhood, which may later influence the likelihood of the child’s substance abuse during adolescence.Whether these proposed mechanisms also apply to cannabis is largely unknown. Moreover, we do not know how the magnitude of these distal effects may differ across substance type. Given that, until very recently, cannabis use was illegal across the United States, it may be reasonable to speculate that the deleterious effect of a cannabis use disorder may be more robust than that of an alcohol use disorder because a cannabis use disorder may encompass a father’s proclivity to engage in illegal behavior (Auty et al., 2015). The first needed step, however, is to determine if a father’s cannabis use disorder influences his child’s uptake of alcohol and cannabis, independent of an alcohol use disorder and pertinent control variables. In this brief report, fathers’ lifetime incidence of an alcohol and cannabis use disorder and their children’s onset of use of these same substances by age 15 is examined.1

Support for the Rochester Youth Development Study has been provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R01CE001572), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (2006-JW-BX-0074, 86-JN-CX-0007, 96-MU-FX-0014, 2004-MU-FX-0062), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA020195, R01DA005512), the National Science Foundation (SBR-9123299), and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH56486, R01MH63386). Work on this project was also aided by grants to the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany, State University of New York, from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30HD32041) and the National Science Foundation (SBR-9512290).

Method

Sample

The data for this study come from two longitudinal, companion studies (Thornberry, 2016). The original study, the Rochester Youth Development Study (RYDS), began in 1988, and the intergenerational extension, the Rochester Intergenerational Study (RIGS), began in 1999. The original RYDS sample of 1,000 adolescents (referred to here as G2, for Generation 2) is representative of the seventh-and eighth-grade public school population of Rochester, NY, in 1988. Youth at high risk for antisocial behavior were overrepresented by oversampling boys (73% males) and families living in high-crime areas of the city. RYDS participants completed regular interviews in school or their home every 6 months from 1988 to 1992 (Phase 1), annually from 1994 to 1996 (Phase 2), and biannually from 2003 to 2006 (Phase 3). G2’s primary caregiver, G1, also participated in interviews during Phases 1 and 2.

Beginning in 1999, RIGS selected G2’s oldest biological child (G3) and added new firstborns as the child turned 2 in each subsequent year. Both the focal RYDS participant and firstborn child’s other primary caregiver (93% of other caregivers for RYDS fathers are the child’s biological mother) completed annual interviews since the inception of RIGS, and the child completed annual interviews once he or she turned age 8. Currently, there are data on 531 parent–child dyads—186 mother–child dyads and 345 father–child dyads. This represents 84% of eligible families, and 86% of the families enrolled in RIGS have been retained through 2015.

The present analysis uses data from the 274 father-child dyads in which the child was born before 2001, allowing the child to have been at least 15 years old in 2015. Based on the fathers’ reports, when the child was 15 years old, 67% of fathers either lived with their child or their child regularly spent the night with them. All data collection procedures were approved by the University at Albany’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Fathers’ lifetime alcohol and cannabis use disorders were measured when the participant was in his late 20s/early 30s using the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule–Version IV (CDIS-IV; Robins et al., 1999) during the participant’s annual interview. Participants who met the criteria for either lifetime abuse or dependence were assigned a 1; those who did not meet the abuse or dependence criteria were assigned a 0. Separate indicators were created for alcohol and cannabis.

Use of alcohol and cannabis by the child was selfreported by the child during RIGS interviews. At the age 8 interview, the child reported if he or she had ever used alcohol (“drink beer, wine or hard liquor without your parent’s permission”) and cannabis (“smoke marijuana, reefer, or weed”) and, if they had, at what age they started using. In subsequent interviews, respondents reported if they had used alcohol (without parent’s permission) and cannabis since the last interview. Using this information from each interview, binary indicators of onset of alcohol use and onset of cannabis use were created, whereby respondents were coded 1 if they initiated use at or before their age 15 interview and 0 if they initiated use after their age 15 interview (or not at all). Substance use onset at or before age 15 was selected because this is in line with previous research identifying problematic outcomes as a result of onset by this age (Odgers et al., 2008) and standards set by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) for early experimentation and uptake.

A set of control variables was included in the analytic models. These included basic demographic variables for the father (race/ethnicity, age at the start of RYDS, years of education, and age at child’s birth). The arrest rate (per 100 people based on Rochester Police Records) of the neighborhood where the father lived at the start of RYDS was included as a control variable because it was used as a sampling parameter. Father’s engagement in delinquent behavior (logged sum of 19 different delinquent acts) in his late 20s/early 30s was also included as a control variable to rule out the possibility that a cannabis use disorder is simply a proxy for a proclivity toward engagement in illegal behavior. Lifetime alcohol and cannabis use disorder for the child’s other caregiver was also included as a control variable, given the tendency for romantic partners’ substance use to be related (Grant et al., 2007; Merikangas et al., 2009). Although the other caregiver’s alcohol and cannabis use disorder statuses are reported separately in the descriptive statistics, for the final logistic regression models used to test the research questions, the two disorders were combined because modeling alcohol and cannabis use disorder status separately resulted in quasi-complete separation of data points.

Contact between father and child from age 10 to 15 was also used as a control variable. The contact variable was created from a two-part question asked of both father and child. First, respondents were asked if they lived with the other at the time of the interview. If they did not live with the other, then they were asked how frequently they spent time together. For fathers, this frequency measure was captured on a 5-point scale (0 = never, 1 = once or twice per year, 2 = less than once per month, 3 = at least once a month, and 4 = at least once a week). For children, this frequency measure was captured on a 4-point scale (0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, and 3 = often). These frequency measures were then modified by assigning those who lived together a score 1 point higher than the maximum. The correlation between the father and child reports was reasonably high (r = .72, p < .001). The father and child reports across time were standardized and then averaged to form a final contact score. Finally, gender of the child was included as a control variable.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted in Mplus, Version 7.4 (Muthen & Muthen, 2010). In a logistic regression equation, children’s early onset of alcohol and cannabis use was regressed on fathers’ lifetime alcohol and cannabis use disorder status while adjusting for the control variables. To properly account for missing data, 10 multiply imputed data sets were created. All analyses were performed on each of the imputed data sets and the results were pooled using the procedures outlined by Rubin (1987).

Results

Descriptive statistics

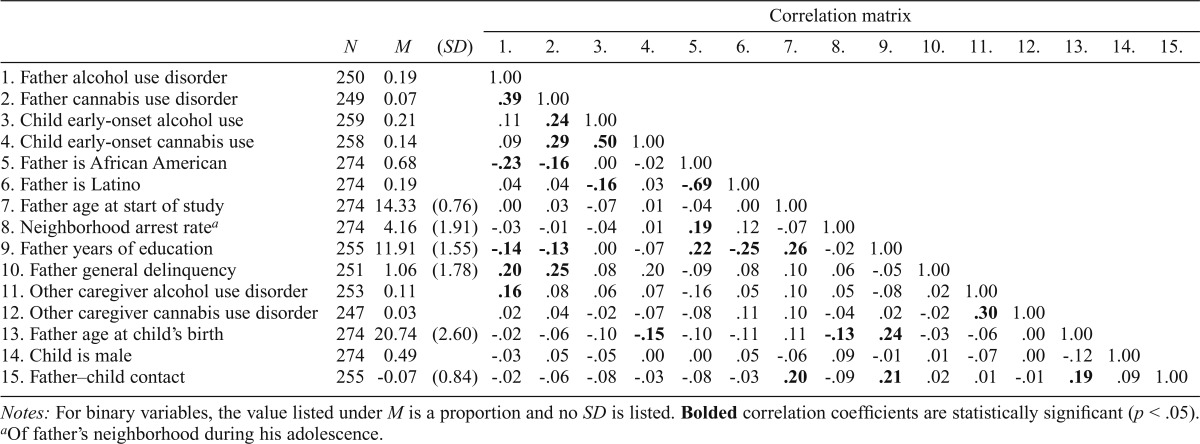

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for all study variables. Bivariate associations between father and child substance use measures are apparent in several instances. Onset of alcohol and cannabis use was more prevalent among children whose fathers met the criteria for an alcohol use disorder (29.8% used alcohol and 19.2% used cannabis by age 15), compared with children whose father did not meet the criteria for an alcohol use disorder (18.2% used alcohol and 11.5% used cannabis by age 15); however, these differences did not meet statistical significance (i.e., p > .05). The differences in child onset as a function of fathers’ lifetime cannabis use disorder were larger. Onset of use of both substances was more prevalent among children whose fathers met the criteria for a cannabis use disorder (56.3% used alcohol and 50.0% used cannabis by age 15), compared with children whose fathers did not meet criteria for a cannabis use disorder (17.6% used alcohol and 10.4% used cannabis by age 15). The relationship between fathers’ cannabis use disorder and children’s early onset of substance use was significant for both early alcohol use, χ2(1) = 13.87, p < .001, and early cannabis use, χ2(1) = 20.57, p < .001.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for all study variables

| N | M | (SD) | Correlation matrix |

|||||||||||||||

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | ||||

| 1. Father alcohol use disorder | 250 | 0.19 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Father cannabis use disorder | 249 | 0.07 | .39 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 3. Child early-onset alcohol use | 259 | 0.21 | .11 | .24 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 4. Child early-onset cannabis use | 258 | 0.14 | .09 | .29 | .50 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 5. Father is African American | 274 | 0.68 | -.23 | -.16 | .00 | -.02 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 6. Father is Latino | 274 | 0.19 | .04 | .04 | -.16 | .03 | -.69 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 7. Father age at start of study | 274 | 14.33 | (0.76) | .00 | .03 | -.07 | .01 | -.04 | .00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 8. Neighborhood arrest ratea | 274 | 4.16 | (1.91) | -.03 | -.01 | -.04 | .01 | .19 | .12 | -.07 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 9. Father years of education | 255 | 11.91 | (1.55) | -.14 | -.13 | .00 | -.07 | .22 | -.25 | .26 | -.02 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 10. Father general delinquency | 251 | 1.06 | (1.78) | .20 | .25 | .08 | .20 | -.09 | .08 | .10 | .06 | -.05 | 1.00 | |||||

| 11. Other caregiver alcohol use disorder | 253 | 0.11 | .16 | .08 | .06 | .07 | -.16 | .05 | .10 | .05 | -.08 | .02 | 1.00 | |||||

| 12. Other caregiver cannabis use disorder | 247 | 0.03 | .02 | .04 | -.02 | -.07 | -.08 | .11 | .10 | -.04 | .02 | -.02 | .30 | 1.00 | ||||

| 13. Father age at child’s birth | 274 | 20.74 | (2.60) | -.02 | -.06 | -.10 | -.15 | -.10 | -.11 | .11 | -.13 | .24 | -.03 | -.06 | .00 | 1.00 | ||

| 14. Child is male | 274 | 0.49 | -.03 | .05 | -.05 | .00 | .00 | .05 | -.06 | .09 | -.01 | .01 | -.07 | .00 | -.12 | 1.00 | ||

| 15. Father–child contact | 255 | -0.07 | (0.84) | -.02 | -.06 | -.08 | -.03 | -.08 | -.03 | .20 | -.09 | .21 | .02 | .01 | -.01 | .19 | .09 | 1.00 |

Notes: For binary variables, the value listed under M is a proportion and no SD is listed. Bolded correlation coefficients are statistically significant (p < .05).

Of father’s neighborhood during his adolescence.

There was substantial overlap in alcohol and cannabis use disorders for fathers, χ2(1) = 38.14,p < .001; 76.5% of men who met the criteria for a cannabis use disorder also met the criteria for an alcohol use disorder, and 27.1% of men who met the criteria for an alcohol use disorder also met the criteria for a cannabis use disorder. Likewise, there was substantial overlap in early onset of alcohol and cannabis use by the children, χ2(1) = 64.2, p < .001; 71.4% of children who initiated cannabis use by age 15 had also initiated alcohol use, and 47.2% of children who initiated alcohol use by age 15 had also initiated cannabis use.

Logistic regression models of child’s early onset of substance use

The results of the logistic regression models predicting child’s use of alcohol and cannabis by age 15 are reported in Table 2. Children of fathers with a lifetime cannabis use disorder were more likely to have initiated both alcohol (odds ratio = 6.71, 95% CI [1.92, 23.52]) and cannabis (odds ratio = 8.13, 95% CI [2.07, 31.95]) use by age 15. Incidence of a lifetime alcohol use disorder was not a significant predictor of children’s early onset of either alcohol or cannabis use.

Table 2.

Odds ratios (ORs) from logistic regression models regressing child substance use on father’s substance use disorders and control variables

| Child early alcohol use |

Child early cannabis use |

|||

| Variable | OR | [95% CI] | OR | [95% CI] |

| Father alcohol use disorder | 0.93 | [0.36, 2.42] | 0.89 | [0.27, 2.92] |

| Father cannabis use disorder | 6.71** | [1.92, 23.52] | 8.13** | [2.07, 31.95] |

| Father is African American | 0.30* | [0.10, 0.96] | 1.23 | [0.29, 5.21] |

| Father is Latino | 0.06** | [0.01, 0.31] | 0.99 | [0.20, 4.91] |

| Father age at start of study | 0.72 | [0.44, 1.16] | 0.94 | [0.53, 1.66] |

| Neighborhood arrest ratea | 1.04 | [0.85, 1.28] | 1.00 | [0.79, 1.27] |

| Father years of education | 1.10 | [0.86, 1.41] | 1.02 | [0.80, 1.32] |

| Father general delinquency | 1.09 | [0.92, 1.30] | 1.22 | [0.97, 1.53] |

| Other caregiver alcohol or cannabis use disorder | 0.98 | [0.32, 3.07] | 1.27 | [0.36, 4.48] |

| Father age at child’s birth | 0.84* | [0.73, 0.98] | 0.80* | [0.65, 0.98] |

| Child is male | 0.69 | [0.35, 1.37] | 0.87 | [0.40, 1.88] |

| Father–child contact | 0.86 | [0.54, 1.38] | 1.16 | [0.71, 1.91] |

Notes: CI = confidence interval.

Of father’s neighborhood during his adolescence.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Discussion

Although the effects of parental substance use on children’s use of substances have been the focus of numerous studies, little work has been done to examine these types of relationships using prospective, longitudinal, and intergenerational data. Using a rigorous study design, the importance of a father’s lifetime cannabis use disorder on his child’s early onset of alcohol and cannabis use was identified. Regardless of a father’s history of an alcohol use disorder and when pertinent demographic variables and potential confounders were controlled for, the children of fathers who met the criteria for a lifetime cannabis use disorder were more likely to report an early onset of alcohol and cannabis use. Given the short-and long-term consequences of early onset substance use by children (Odgers et al., 2008), this etiological finding has significant public health relevance, pointing to fathers’ cannabis use disorder as a key risk factor for children’s early onset of substance use.

Although this study makes an important contribution to the literature, it is important to recognize the limitations. First, the sample size used in this research is relatively small (n = 274), and power to detect small effects is therefore low. Second, the prevalence of substance use disorders in the RYDS/RIGS sample was lower than in the general population. However, substance use disorders are known to be less common in African American and Latino populations than in White populations (Grant et al., 2015, 2016). Third, individuals who delayed parenthood into their later 20s or older were not represented in the findings presented here because their firstborns had not yet aged into adolescence. It will be important to revisit these analyses 4 to 5 years from now when the full sample of children has passed through adolescence. Fourth, the Rochester studies represent families who lived in Rochester, NY, in the mid-1980s, and the extent to which these findings generalize to other populations is unknown. Fifth, the Rochester studies represent mostly African American and Latino families, and the extent to which these findings generalize to other populations with different demographic and racial/ethnic backgrounds is an important topic for future research.

Despite these limitations, this study highlights the potentially important influence of a father’s lifetime cannabis use disorder on his child’s early uptake of alcohol and cannabis. Further research is needed to replicate these findings. Future research is also needed to determine why fathers’ cannabis use disorder is predictive of children’s use of alcohol and cannabis. For example, it will be important to determine if affected children are more likely to demonstrate maladaptive development in early childhood (Edwards et al., 2001), if there is a genetic basis to the interfamilial continuity of substance use demonstrated here (Han et al., 2012), or if a cannabis use disorder affects the quality of parenting offered by the father or the family context he creates (Chassin et al., 1993; Handley & Chassin, 2013; Latendresse et al., 2008). Answers to these questions are paramount to the development, implementation, and timing of prevention and intervention initiatives aimed at delaying the onset of substance use by children.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Rebekah Chu, Ph.D., for her assistance in compiling the data set for the analyses presented in this brief report.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflicts of interest exist for this work.

Footnotes

The initial intent was to study these relationships for both father–child and mother–child dyads; however, only three mothers in the sample qualified for a cannabis use disorder. This small number precluded the possibility of answering the proposed research questions with the current sample.

References

- Auty K. M., Farrington D. P., Coid J. W. The intergenerational transmission of criminal offending: Exploring gender-specific mechanisms. British Journal of Criminology. 2015;57:215–237. doi:10.1093/bjc/azv115. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. A., Hill K. G., Guttmannova K., Epstein M., Abbott R. D., Steeger C. M., Skinner M. L. Associations between parental and grandparental marijuana use and child substance use norms in a prospective, three-generation study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.010. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D. M., Tiberio S. S., Kerr D. C. R., Pears K. C. The relationships of parental alcohol versus tobacco and marijuana use with early adolescent onset of alcohol use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;77:95–103. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.95. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L., Curran P. J., Hussong A. M., Colder C. R. The relation of parent alcoholism to adolescent substance use: A longitudinal follow-up study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:70–80. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L., Fora D. B., King K. M. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L., Pillow D. R., Curran P. J., Molina B. S., Barrera M., Jr Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: A test of three mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:3–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.3. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E. P., Leonard K. E., Eiden R. D. Temperament and behavioral problems among infants in alcoholic families. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:374–392. doi: 10.1002/imhj.1007. doi:10.1002/imhj.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Goldstein R. B., Saha T. D., Chou S. P., Jung J., Zhang H., Hasin D. S. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant B. F., Saha T. D., Ruan W. J., Goldstein R. B., Chou S. P., Jung J., Hasin D. S. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:39–47. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. D., Heath A. C., Bucholz K. K., Madden P. A. F., Agrawal A., Statham D. J., Martin N. G. Spousal concordance for alcohol dependence: Evidence for assortative mating or spousal interaction effects? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:717–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00356.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Yang B.-Z., Kranzler H. R., Oslin D., Anton R., Farrer L. A., Gelernter J. Linkage analysis followed by association show NRG1 associated with cannabis dependence in African Americans. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;72:637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.038. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley E. D., Chassin L. Alcohol-specific parenting as a mechanism of parental drinking and alcohol use disorder risk on adolescent alcohol use onset. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:684–693. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.684. doi:10.15288/jsad.2013.74.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D. S., Kerridge B. T., Saha T. D., Huang B., Pickering R., Smith S. M., Jung J., Grant B. F. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, 2012–2013: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;173:588–599. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15070907. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15070907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong A. M., Huang W., Serrano D., Curran P. J., Chassin L. Testing whether and when parent alcoholism uniquely affects various forms of adolescent substance use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:1265–1276. doi: 10.1007/s10802-012-9662-3. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9662-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latendresse S. J., Rose R. J., Viken R. J., Pulkkinen L., Kaprio J., Dick D. M. Parenting mechanisms in links between parents’ and adolescents’ alcohol use behaviors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:322–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00583.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., Li J. J., Stipelman B., Yu K., Fucito L., Swendsen J., Zhang H. The familial aggregation of cannabis use disorders. Addiction. 2009;104:622–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02468.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L. K., Muthen B. O.2010)Mplus user’s guide 6th ed.Los Angeles, CA: Authors [Google Scholar]

- Odgers C. L., Caspi A., Nagin D. S., Piquero A. R., Slutske W. S., Milne B. J., Moffitt T. E. Is it important to prevent early exposure to drugs and alcohol among adolescents? Psychological Science. 2008;19:1037–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02196.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Dawson D., Frick U., Gmel G., Roerecke M., Shield K. D., Grant B. Burden of disease associated with alcohol use disorders in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38:1068–1077. doi: 10.1111/acer.12331. doi:10.1111/acer.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins L. N., Cottler L. B., Bucholz K. K., Compton W. M., North C. S., Rourke K. M. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV) St. Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin D. B. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson F. S., Grant B. F., Dawson D. A., Ruan W. J., Huang B., Saha T. Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;80:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The TEDS Report: Age of substance use initiation among treatment admissions aged 18 to 30. Rockville, MD: Author; 2014. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/WebFiles_TEDS_SR142_AgeatInit_07-10-14/TEDS-SR142-AgeatInit-2014.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry T. P.2016Three-generation studies: Methodological challenges and promise Shanahan M. J., Mortimer J. T., Johnson M. K.Handbook of the life course, Vol. 2571–596.New York, NY: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N. D., Swanson J. M., Evins A. E., DeLisi L. E., Meier M. H., Gonzalez R., Baler R. Effects of cannabis use on human behavior, including cognition, motivation, and psychosis: A review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:292–297. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3278. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]