Abstract

Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein (THP) is expressed exclusively in the kidney and constitutes the most abundant protein in mammalian urine. A critical role for THP in antibacterial host defense and inflammatory disorders of the urogenital tract has been suggested. We demonstrate that THP activates myeloid DCs via Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) to acquire a fully mature DC phenotype. THP triggers typical TLR signaling, culminating in activation of NF-κB. Bone marrow–derived macrophages from TLR4- and MyD88-deficient mice were nonresponsive to THP in contrast to those from TLR2- and TLR9-deficient mice. In vivo THP-driven TNF-α production was evident in WT but not in Tlr4–/– mice. Importantly, generation of THP-specific Abs consistently detectable in urinary tract inflammation was completely blunted in Tlr4–/– mice. These data show that THP is a regulatory factor of innate and adaptive immunity and therefore could have significant impact on host immunity in the urinary tract.

Introduction

Professional APCs, such as DCs, are pivotally positioned at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity (1). Recognition of pathogens leads to a typical maturation program including upregulation of costimulatory and MHC molecules, migration of DCs to adjacent lymph nodes, and subsequent priming of naive antigen-specific T cells. For pathogen recognition, DCs are specifically equipped with distinct pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (2, 3). Microbial components recognized by TLR have been identified for TLR2 (e.g., peptidoglycan), TLR3 (e.g., double-stranded RNA), TLR4 (e.g., LPS), TLR5 (bacterial flagellin), TLR6 (e.g., mycoplasmal macrophage-activating lipopeptide 2 kDa), TLR9 (e.g., unmethylated bacterial CpG DNA), and TLR11 (uropathogenic bacteria) (4, 5). Moreover, various conserved sugar residues have been shown to be involved in accessory cell stimulation in concert with TLR-dependent cellular activation by putative lectin-binding receptors (6–8). Recently, distinct host-derived molecules such as fibronectin, hyaluronic acid, or β-defensin 2 have also been shown to signal through TLR (9–11). Hence, TLRs are thought to essentially contribute to transduce signals by exogenous as well as endogenous molecules to activate distinct immune cells or to control tissue integrity, respectively (12).

Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein (THP), or uromodulin, is the most abundant protein in normal human urine, present at 30–50 mg/24 hour (13). It is expressed only in the thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop in the kidney, and it is cleaved from its GPI anchor to be secreted into the urine. The relative abundance and specific localization of THP indicates an important physiological role in the urinary tract, which still remains to be elucidated. Numerous clinical and experimental studies have indicated an involvement of THP in several forms of inflammatory kidney disease (13–15). Importantly, anti-THP Abs are consistently found in the peripheral blood of patients with interstitial nephritis or urinary tract infection (15, 16). THP constitutes the matrix of all urinary stones, and there is a well-known relationship between interstitial stone deposition and surrounding leukocytes (17). Recent studies have shown a proinflammatory role of THP through triggering of inflammatory molecule induction in human monocytes as well as in granulocytes (18, 19). Significantly, recent data indicated a role for THP in the antibacterial defense system of the urinary tract, since THP KO mice were highly susceptible to severe urinary bladder and kidney infection (20, 21).

We hypothesized that THP governs the performance of professional APCs such as DCs, thereby affecting local immune responsiveness. We show here that immature DCs exposed to THP develop into fully mature DCs. The molecular action of THP was dependent on TLR4 signaling and resulted in NF-κB activation. In vivo application of THP induced a prominent anti-THP Ab response that was fully blunted in TLR4 KO mice. The immunostimulatory effects of THP by TLR4 could represent an important host defense mechanism employed in the human urinary tract system.

Results

THP induces phenotypic maturation of human monocyte-derived DCs.

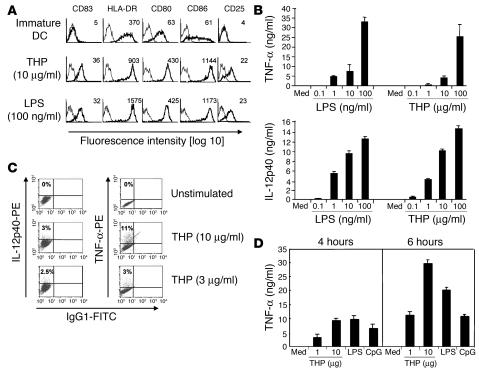

We first sought to determine whether THP is able to induce maturation of immature DCs as reflected by phenotypic changes. DCs exposed to THP for 48 hours expressed the typical DC maturation markers CD83 and CD25 (Figure 1A). Furthermore, the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, as well as the antigen-presenting molecule HLA-DR, were upregulated. These phenotypic features exactly matched the DC maturation profile induced by LPS (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

THP activates professional APCs. (A) Immature monocyte-derived human DCs were stimulated with THP or LPS. Profiles with fine lines represent staining patterns with an isotype-matched control Ab, and profiles with bold lines represent staining with mAb of the indicated specificity. Data are representative of 5 independent experiments. Numbers indicate mean fluorescence intensity of specific Ab staining. (B) Immature human DCs were stimulated with different concentrations of THP or LPS. Cell-free supernatants were collected 18 hours after addition of THP or LPS and were analyzed by ELISA. Med, medium control. (C) Intracellular cytokines were stained in human DCs 18 hours after stimulation and then analyzed by FACS. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Mouse RAW264.7 macrophages were exposed to THP, LPS, and CpG for the indicated time periods. Cell-free supernatants were analyzed for TNF-α by ELISA. Similar results were obtained in 3 other independent experiments and data are expressed as means ± SD of triplicate cultures in a representative experiment.

In addition, maturation of DCs as reflected by IL-12p40 and TNF-α production was examined in THP- or LPS-stimulated DCs. THP was a potent inducer of proinflammatory cytokine secretion (Figure 1B) and production (Figure 1C). We also studied whether THP had effects on murine myeloid cells. THP induced cytokine production in splenocytes, bone marrow–derived immature DCs, and the murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1D and data not shown). These data indicate that THP potently stimulates myeloid immunocompetent cells leading to cytokine production and final maturation of immature monocyte-derived DCs.

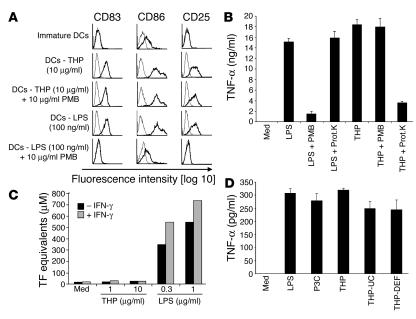

LPS at concentrations as low as 50 pg/ml has been described to activate myelomonocytic cells (22). To exclude the possibility that LPS contamination of the THP preparation had caused immune cell stimulation, we first tested for their endotoxin content the materials used for DC culturing and found them to be endotoxin free (<0.06 U/ml) as confirmed by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (data not shown). Furthermore, we preincubated the THP probe with polymyxin B, a specific inhibitor for LPS, before adding it to immature DCs. DC maturation induced by THP was independent of LPS, since polymyxin B did not affect THP-induced DC maturation but completely prevented activation by LPS (Figure 2A). Similarly, absorption over a polymyxin B column, which effectively eliminates LPS, did not affect TNF-α production induced by the THP preparation but abolished the response to LPS (Figure 2B). Conversely, proteinase K treatment did not inhibit LPS-induced TNF-α production but restrained activation by THP.

Figure 2.

DC maturation induced by THP is not due to LPS or protein contamination. (A) THP and LPS were left untreated or pretreated with polymyxin B (PMB) for 2 hours and then added to human immature DCs. After 48 hours, cells were harvested and analyzed by FACS. Profiles with fine lines represent staining patterns with an isotype-matched control Ab, and profiles with bold lines represent staining with a mAb of the indicated specificity. Data are representative of 5 independent experiments. (B) THP was incubated with PMB beads overnight. The supernatant was analyzed for the presence of THP by SDS-PAGE. Additionally, THP was incubated with proteinase K (Prot.K) for 45 minutes as described (11). The PMB-purified and the proteinase-treated samples were incubated with RAW 264.7 macrophages for 18 hours and analyzed for TNF-α. LPS as a control was treated similarly. Similar results were obtained in another independent experiment. (C) Effect of THP and LPS on the induction of TF activity in HUVECs. HUVECs were pretreated with or without IFN-γ and then exposed to THP or LPS. A 1-stage clotting assay was used to determine TF activity. The results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) LPS, Pam3Cys (P3C), THP isolated by standard NaCl precipitation (THP), THP isolated by NaCl precipitation and ultracentrifugation (THP-UC), and THP isolated by NaCl precipitation, ultracentrifugation, and diatomaceous earth filter (THP-DEF) were added to C57BL/6 splenocytes for 20 hours. Cell-free supernatants were analyzed for TNF-α by ELISA.

Furthermore, we sought to determine a potential functional effect of possible LPS contamination in the THP preparation. Recent data demonstrated that THP, in contrast to LPS, is not able to stimulate the expression of tissue factor (TF) in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (18). LPS induced TF expression in HUVECs, whereas THP was not able to induce TF in endothelial cells even in IFN-γ–pretreated cells that are highly sensitive to LPS (Figure 2C). These results suggest a functional difference in LPS and THP signaling. Collectively, these experiments rule out the possibility that the effects of THP on DCs are due to contamination with LPS.

To exclude contaminating molecules other than LPS, the standard THP preparation obtained by repeated NaCl precipitation from urine was further purified by 2 sequential procedures taking advantage of the fact that THP forms a gel when monovalent ions above 60 mM are present. After induction of gel formation by 70 mM sodium phosphate, THP was purified by ultracentrifugation (23). The pellet fraction containing THP was fully active on C57BL/6 splenocytes for TNF-α and IL-6 production (Figure 2D and data not shown). Moreover, the ultracentrifuged THP was further purified over a diatomaceous earth filter, which is known to purify THP to homogeneity (24). This THP preparation highly purified by 3 different methods was still able to induce TNF-α production (Figure 2D). These data strongly indicate that THP but not other possible contaminants stimulates myeloid cells to induce cytokine production.

Functional consequences of THP-induced DC maturation.

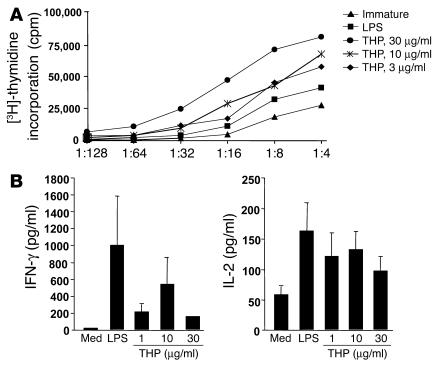

Another hallmark of mature DCs is their ability to trigger potent T cell stimulation. THP-activated human DCs were used as stimulator cells in a standard mixed lymphocyte culture (MLC). Interaction of THP with immature DCs led to a dramatic enhancement of their stimulatory capacity (Figure 3A). Further analysis of T cell cytokine production revealed that high levels of IL-2 and IFN-γ existed in allogeneic T cell cultures challenged with THP-treated DCs (Figure 3B). These data demonstrate a strong T cell responsiveness that occurs after activation of immature DCs by THP.

Figure 3.

Induction of T cell stimulatory capacity and type 1 immune responsiveness by THP. (A) Immature human monocyte-derived DCs were stimulated with THP or LPS, washed extensively, irradiated, and subsequently cocultured with highly purified allogeneic T cells at the indicated ratios. After 48 hours, the cells were used as allogeneic stimulators as described above. DNA synthesis was assessed on day 5 and is expressed as mean counts per minute of a representative experiment. SD of triplicates were generally below 20%. Similar results were obtained in 4 other experiments. (B) For T cell cytokine production, immature DCs were stimulated with THP at the indicated concentrations or LPS, extensively washed, irradiated, and subsequently cocultured with highly purified allogeneic T cells at a DC/T cell ratio of 1:2. Cell-free supernatants were collected and analyzed by ELISA for IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 4 different donor combinations.

THP induces activation of p38-MAPK, ERK-1/2, and Akt.

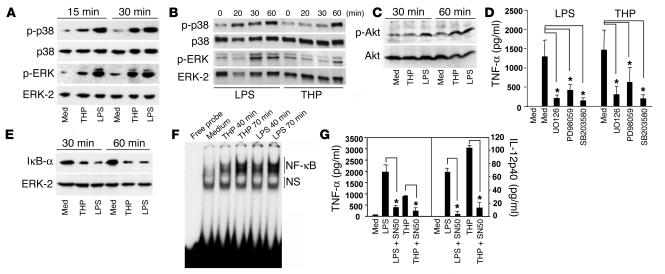

DC maturation has been shown to be associated with phosphorylation of distinct tyrosine kinases, including ERK, p38, and Akt (25). Addition of THP to human DCs (Figure 4A) or murine macrophages (Figure 4B) led to rapid phosphorylation of p38-MAPK and ERK within 15–30 minutes. Interestingly, we consistently found delayed kinetics of p38 and ERK phosphorylation compared with LPS. Next, we analyzed the PI3K/Akt pathway, which is involved in activation and survival of many cell types, including DCs (25). The peak of Akt phosphorylation in LPS-stimulated DC cultures was detected after 30 minutes, whereas THP-stimulated DCs also exhibited a kinetic shift as seen in the MAPK activation profile (Figure 4C). Highly selective inhibitors of ERK-1/2 (PD98059 and UO126) or p38 (SB203580) effectively blocked THP-induced TNF-α production in immature DCs, demonstrating a requirement of MAPK activation for cytokine production (Figure 4D). These results indicate that THP engages DC-signaling pathways similar to those of LPS and point to a critical involvement of MAPK phosphorylation in THP-mediated DC activation.

Figure 4.

Immunostimulatory effects of THP are dependent on p38-, ERK-1/2–MAPK kinase and NF-κB signaling. Immature human DCs (A) or murine macrophages (B) were incubated with THP, LPS, or medium. Subsequently, phospho-p38 (p-p38) and phospho–ERK-1/2 (p-ERK) were determined by immunoblotting; p38 and ERK-2, respectively, were detected from stripped membranes. Blots are representative of 4 independent experiments. (C) Immature DCs were incubated with THP, LPS, or medium, and phospho-Akt (p-Akt) as well as total Akt were determined from whole cell lysates by immunoblotting. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (D) Immature human DCs preincubated with or without the indicated MAPK inhibitors were exposed to THP, LPS, or medium. Cell-free supernatants were collected after 18 hours and were analyzed for TNF-α by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 4 different donor combinations. *Significantly different from the values for stimulated control; P < 0.05. (E) Immature DCs were incubated with THP, LPS, or medium, and immunoblotting was performed from whole-cell lysates using Abs against IκB-α and ERK-2. (F) THP, LPS, or medium was added to immature human DCs. Oligonucleotides labeled with 32P, containing a NF-κB consensus sequence, were incubated with nuclear extracts followed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. Similar results were obtained in 2 independent experiments. (G) Immature human DCs preincubated with or without the NF-κB inhibitor SN50 were exposed to THP, LPS, or medium. Cell-free supernatants were collected after 18 hours and were analyzed for cytokines by ELISA. Data are representative of 4 independent experiments. *Significantly different from the values for stimulated control; P < 0.05.

THP activates the NF-κB–signaling pathway in immature DCs.

Transactivation of NF-κB is essential for proper DC maturation (26). Degradation of IκB-α in THP-stimulated DCs indicated activation of the NF-κB–signaling pathway (Figure 4E). To directly assess nuclear translocation of NF-κB, electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) of nuclear extracts were performed. THP induced NF-κB translocation in a time-dependent manner, detecting prominent signals 40 minutes after stimulation (Figure 4F). Inhibition of cytokine production by the specific NF-κB inhibitor SN50 that was recently shown to prevent LPS-mediated NF-κB transactivation in DCs (25) further corroborated these findings (Figure 4G). These data indicate that activation of NF-κB is a prerequisite for successful activation of immature DCs by THP.

Involvement of TLR4 in the immunostimulatory effects of THP.

The overlapping activation pattern accomplished by THP and LPS prompted us to assess a possible role of the TLR-signaling pathway in the immunostimulatory effects exerted by THP. Here we show that IL-1 receptor–associated kinase 1 (IRAK-1), a serine/threonine kinase involved in early TLR-mediated NF-κB activation (27), was degraded in THP-stimulated immature human DCs in a time-dependent manner (Figure 5A). Furthermore, selective inhibition of TIRAP, a critical adaptor protein in the signaling pathway downstream of TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, and TLR6, but not TLR5, TLR7, and TLR9 (28), by a TIRAP/Mal inhibitory peptide abrogated THP-induced cytokine production in murine DCs (Figure 5B). To investigate a role of TLR4 in THP-induced immune cell activation, human DCs were preincubated with the anti-TLR4 Ab, mAb HTA-125, and a significant impairment of cytokine production was observed (Figure 5C). These results indicate a critical role of TLR4 in THP-mediated immunostimulatory effects on DCs.

Figure 5.

Involvement of TLR signaling in APC activation by THP. (A) Immature human DCs were incubated with THP, LPS, or medium, and immunoblotting was performed from whole-cell lysates using antibodies against IRAK-1 and ERK-2, which served as loading control. A representative of 4 independent experiments is shown. (B) Bone marrow–derived murine DCs (BM-DCs) were treated with or without TIRAP/Mal peptide followed by stimulation with THP or LPS. After 18 hours, cell-free supernatants were collected and analyzed by ELISA. (C) Immature human DCs were pretreated with a mAb against TLR4 (HTA125) or a control mAb before addition of LPS or THP. Cell-free supernatants were then collected and analyzed by ELISA. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. mDCs, monocyte-derived DCs. *Significantly different from the values for stimulated control; P < 0.05.

Impaired cytokine production upon stimulation with THP in MyD88- and TLR4-null, but not in TLR2- and TLR9-null, mice.

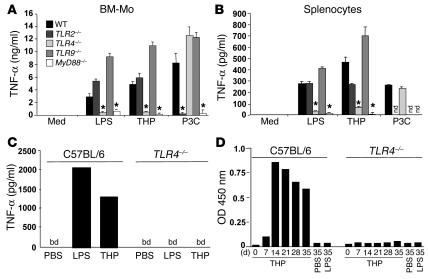

To obtain direct evidence of TLR activation upon THP engagement, we isolated bone marrow–derived macrophages from MyD88 and TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 KO mice as well as from WT mice. While THP potently stimulated TNF-α production in APCs obtained from WT, TLR2–/–, and TLR9–/– mice, cells from TLR4–/– and MyD88–/– mice were completely resistant to THP or LPS stimulation (Figure 6A). Importantly, myeloid cells from TLR4–/– mice were functionally active, since they fully responded to the TLR2 agonist Pam3Cys (Figure 6, A and B).

Figure 6.

The immunomodulatory effects of THP are exerted by a TLR4-dependent mechanism. Bone marrow–derived murine macrophages (BM-Mo) (A) or murine splenocytes (B) from C57BL/6 WT, TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, or Myd88 KO mice were stimulated with THP, LPS, or Pam3Cys. Cell-free supernatants were collected 18 hours after addition of LPS, THP, or Pam3Cys and analyzed for TNF-α by ELISA. nd, not determined. *Significantly different from the values for activated controls in WT mice; P < 0.001. (C) Analysis of in vivo cytokine production in serum of C57BL/6 mice or TLR4 KO mice after i.v. administration of LPS or THP. One-hour postinjection serum levels of TNF-α were analyzed by ELISA. bd, below detection limit. Similar results were obtained in another independent experiment. (D) THP was injected i.v. on days 0, 1, 2, and 7 into C57BL/6 mice or TLR4 KO mice, and the subsequent THP-specific Ab response (IgG) was determined by ELISA. Ab response is shown at a serum dilution of 1:500.

To analyze cytokine production in vivo, WT and TLR4–/– mice were challenged with intravenous administration of THP. One hour after THP or LPS injection, high levels of TNF-α were detected in WT mice (Figure 6C). In contrast, no detectable amounts of TNF-α were observed in TLR4–/– mice challenged with THP, indicating a complete unresponsiveness toward the immunostimulatory effects of the glycoprotein. Thus, the prominent proinflammatory cytokine induction by THP in vivo occurs by a TLR4-dependent mechanism.

THP-mediated Ab production in vivo is abrogated in TLR4–/– mice. Increased production of THP-specific autoantibodies is a consistent finding in several inflammatory disorders and infections of the urinary tract (13, 29, 30). Furthermore, THP has previously been shown to be a powerful autoantigen when rats, mice, or rabbits were challenged with autologous THP (31–33). We therefore were interested in the involvement of the TLR4-signaling pathway in the induction of an Ab response against THP. We detected a prominent IgG response in C57BL/6 mice within 7 days after intravenous THP delivery (Figure 6D). While WT mice displayed a typical Ab kinetic over a period of 35 days, TLR4–/– mice were dramatically impaired in their ability to produce specific Abs in response to THP challenge (Figure 6D). LPS was not able to induce any Ab response in both mouse strains (Figure 6D). These data show that TLR4 plays a pivotal role not only in THP-induced proinflammatory cytokine production, but also in the emergence of an anti–THP-directed immune response.

Discussion

DCs link the innate with the adaptive immune system by their ability to sense different microbial stimuli and conveying this information to lymphocytes. This process is accomplished by pathogen recognition and subsequent induction of the DC maturation program comprising increased surface expression of costimulatory molecules, cytokine production, and potent antigen-presenting function. In this study the unique property of the abundant urinary glycoprotein THP to activate professional APCs such as DCs is demonstrated to involve functional TLR4 signaling. Furthermore, THP-specific humoral immune responsiveness was found to be severely impaired in the absence of intact TLR4 signaling, indicating a failure to implement APC-driven specific immune cell activation.

Numerous clinical and experimental studies have indicated an involvement of THP in several forms of inflammatory kidney disease. While THP is normally expressed at the luminal surface of renal tubular epithelial cells and excreted into the urine, its aberrant presence was also detected at the basolateral surface and in interstitial infiltrates in several inflammatory kidney diseases (34–36). Earlier studies indicated a role of THP in the pathogenesis of interstitial nephritis, since intravenous challenge of animals with THP resulted in the induction of a tubulointerstitial inflammatory response and microscopic scarring localized to the distal nephron segments (31–34). Furthermore, cytotoxic T cells with specificity for THP and anti-THP Abs were present in affected animals. Ab responses to THP are a well-known phenomenon in patients with infections of the urinary tract such as interstitial cystitis (37, 38) and acute pyelonephritis (30, 39, 40), where THP has been discussed to be involved in kidney scarring leading to overt renal insufficiency (29, 41). Moreover, elevated autoantibody levels against THP could be involved in chronic pyelonephritis and subsequent renal damage (15, 16). Abnormal deposition of THP and ensuing inflammatory reactions have been consistently observed in cast nephropathy and urolithiasis (13, 16). In acute renal transplant rejection THP deposits were found to be surrounded by mononuclear cell infiltrates (42), similar to kidneys affected by immunoglobulin light chain deposition in patients with multiple myeloma (43). Despite the apparent participation of THP in a large variety of inflammatory kidney diseases, the underlying mechanisms that would explain how THP contributes to inflammatory reactions have largely remained obscure.

In the present study we clearly show that THP is able to induce maturation of immature DCs by a TLR4-dependent mechanism. Moreover, our study is in line with previous findings demonstrating that intravenous challenge with THP or autologous urine results in rapid induction of THP Abs. Remarkably, TLR4 is essential for the THP-specific Ab response in the present model as Tlr4–/– mice were severely impaired in their THP-specific humoral immune responsiveness. In this respect, THP might be regarded as both adjuvant and antigen because it stimulates its own Ab production. Presumably, healthy mammals do not raise Abs against THP because the exclusive localization of THP at the luminal surface of tubular epithelial cells keeps the protein from the Ab-producing machinery. Segregation could be abolished in kidney diseases by loss of cell integrity or of luminal/basolateral tubular polarization. The physiological function of THP, therefore, could come from its ability to immediately activate innate immune responses, also recruiting components of the adaptive arm of the immune system. THP could thereby provide a critical danger signal to prevent host invasion of potentially harmful bacteria in case of local injury or increased epithelial permeability. While considered as a glycoprotein with direct antimicrobial effects, as has been suggested in recent studies employing THP–/– mice (20, 21), our data indicate a further role of THP as an endogenous activator of local immune responsiveness.

Various investigators have pointed to the problem of sufficiently high purity of potential immunostimulatory molecules acting through TLR. Therefore, it is of note that a number of data in the present as well as in previous studies (18, 44) confirmed that the results obtained with THP are not due to contaminating LPS. First, polymyxin B, which binds to lipid A and thereby blocks LPS responses, did not affect activation of both human and mouse APCs at all. Second, we found that HUVECs, which respond to very low amounts of LPS with TF production, were completely insensitive toward THP. Finally, the complete lack of response to THP in Tlr4–/– cells rule out possible contaminations with lipoproteins or lipopeptides. We cannot, however, completely eliminate the possibility that THP may act as a potentiator of subthreshold amounts of LPS or some other bacterial cell wall components that are tightly bound within the THP molecule and that might directly stimulate TLR4. Even in this case, however, THP could play a significant antibacterial role by amplifying potential danger signals derived from microbes entering the urinary tract and thereby inducing an appropriate antibacterial host response.

Recent studies have identified various sugar structures such as zymosan (7, 8), hyaluronic acid (10), or phospholipomannan (6) as effective activators of myeloid cells. In these studies an absolute requirement was demonstrated for the engagement of TLR2, TLR4, or both receptors for proper immune cell activation. Therefore, it is currently believed that bacterial recognition and subsequent immune cell activation might depend on both a functional TLR complex and a specific sugar-recognizing receptor supporting a model in which specific host responses are mediated by a combination of molecules (3). It was recently shown that zymosan activates immune cells only by engagement of both dectin-1, its respective receptor, and TLR2 (7, 8). The highly complex glycomoiety of THP, which consists of n-linked glycans of the polyantennary-type sialylated, fucosylated, and sulphated sugar residues that are evolutionarily conserved across species (13), might similarly contain ligands for a sugar-recognition receptor. Therefore, further investigations will focus on the identification of the active moiety and a putative cell surface receptor for THP.

In conclusion, we demonstrate here that the abundant urinary glycoprotein THP is a strong activator of professional APCs, including DCs. Its immunostimulatory potential and its ability to induce an anti-THP Ab response depends critically on TLR4 and its subsequent signaling pathway. We hypothesize that THP might serve as an endogenous activator of a molecular machinery typically associated with host responsiveness against bacterial infections. Similar data were recently reported for β-defensin 2, which is also produced by tubular epithelial cells. While similarly considered as peptide with direct antimicrobial activity, β-defensin 2 possesses DC stimulatory properties involving a TLR4-dependent process (11). Our findings thus extend the understanding of THP’s function in antibacterial defense mechanisms and may have broad implications for the regulation of immune responses in the urinary tract.

Methods

Media and reagents.

LPS (Escherichia coli 0111:B4) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH. Human THP isolated from sterile urine from healthy individuals, purified by 3 repetitive cycles of precipitation in 0.58 M NaCl and centrifugation as described (45), was purchased from Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp. Purity was assessed through a single homologous band at 92 kDa in SDS-PAGE. Mouse THP was purified from sterile urine from female C57BL/6 mice by precipitation in 0.58 M NaCl as described (46) or by dialysis against PBS using a 50-kDa Spectra/Por Biotech RC dialysis membrane from Spectrum Laboratories Inc. To further purify THP, the THP precipitation was diluted in sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.3, to a concentration of 70 mM to induce THP gel formation and was incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Afterward, the sample was ultracentrifuged at 109,000 g for 30 minutes at 10°C, and the pellet was dissolved in H2O and dialyzed against water (23). The pellet fraction contained the majority of THP as assessed by SDS-PAGE. The pellet fraction was further purified by bringing the solution to 140 mM NaCl and 250 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, which induces gel formation. The THP sample was then added onto a column containing diatomaceous earth, washed with PBS, and eluted by addition of H2O as described (24). The MAPK inhibitors SB203580, PD98059, and UO126 and the NF-κB inhibitor SN50 were purchased from Calbiochem. Polymyxin B was from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH. Affi-Prep Polymyxin Support was from Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.

All reagents, media, and buffers used in our assays were checked by Limulus amebocyte lysate assays (BioWhittaker Inc.) and contained less than 0.06 U/ml of endotoxin in accordance with the European Community standard value of water injection. The TIRAP/Mal inhibitory peptide (28), consisting of a Drosophila antennapedia sequence positioned at the N-terminal end of TIRAP amino acids 138–145, was synthesized by Fmoc-chemistry. Tripalmitoyl cysteinyl (Pam3Cys) lipopeptide was purchased from EMC Microcollections. Mouse mAb against human TLR4 (HTA125) was from eBioscience. PE-labeled IL-12 and TNF-α mAbs were from BD Biosciences. RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen Corp.) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 10% FCS (HyClone Laboratories Inc.) was used as culture medium. Recombinant human GM-CSF (rhGM-CSF) was obtained from Schering-Plough and rhIL-4 was from Strathmann Biotech GmbH.

Cell separation and preparation of human DCs.

Human PBMCs were isolated by density-gradient centrifugation over endotoxin-free Lymphoprep (Nycomed Pharma A/S). For monocyte enrichment, PBMCs were depleted of T cells by sheep erythrocyte rosetting. Resting T cells were isolated by sheep erythrocyte rosetting and subsequent lysis of remaining erythrocytes at 4°C.

For DC differentiation, enriched monocytes were cultured in 50 ng/ml rhGM-CSF and 10 ng/ml rhIL-4 for 5–7 days. DC activation was induced by THP or LPS addition for 48 hours.

Mouse studies.

Female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Harlan Winkelmann GmbH. Tlr2–/–, Tlr4–/–, Tlr9–/–, and MyD88–/– mice in a C57BL/6 background were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mice were used at age 6–8 weeks. All animal experiments were approved by the veterinary magistrate (MA58/60) of Vienna, Austria. Bone marrow–derived macrophages were prepared by incubation of 107 bone marrow cells with 1 ml conditioned M-CSF medium. For in vivo studies, 50 μg THP or 50 ng LPS in 100 μl PBS were injected intravenously in the tail vein on days 0, 1, 2, and 7. Blood was taken on the indicated days, and Ab levels against THP were measured by ELISA. Briefly, 5 μg/ml THP or OVA were coated on MaxiSorp plates (Nunc A/S) overnight and serial dilutions of blood serum were applied. Specific Ab binding was proven using a peroxidase-conjugated F(ab′)2 fragment of a rabbit anti-mouse Ab provided by Jackson ImmunoResearch.

Phenotypical characterization of DCs by FACS analysis.

For evaluation of surface marker expression, cells were incubated with FITC- or PE-conjugated mAb for 30 minutes at 4°C. For control, nonbinding isotype-matched FITC- and PE-conjugated mouse IgGs were employed. Cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). FITC-conjugated CD25 (2A3), anti–HLA-DR (L243), and anti-CD83 (HB15e), as well as PE-labeled anti-CD80 (L307.4) and anti-CD86 (IT2.2) mAb, were from BD Biosciences.

Measurement of cytokine production and T cell proliferation.

For evaluation of TNF-α and IL-12p40, 5 × 105 DCs were stimulated with THP (10 μg/ml), LPS (100 ng/ml), or CpG (10 μM) in 24-well plates (final volume 1 ml). Cell-free supernatants were harvested 48 hours after addition of the bacterial stimulus. Cytokines were measured by sandwich ELISA using matched-pair Abs. Capture as well as detection Abs against human IL-12p40 were obtained from R&D Systems Inc. Abs against human TNF-α were from BD Biosciences. Standards consisted of human recombinant material from R&D Systems Inc. Assays were set up in duplicates and were performed according to the recommendations of the manufacturers. The lower limit of detection was 20 pg/ml for all cytokines.

Cytoplasmic staining for cytokine production was performed as described (47). Briefly, monensin (5 μM) was added during the last 12 hours of stimulation. DCs were harvested and fixed for 20 minutes at room temperature by adding 100 μl of FIX solution (An der Grub Bio Research GmbH). Subsequently, cells were washed once with 4 ml PBS, resuspended in 100 μl PBS, and permeabilized by the addition of 100 μl PERM solution (An der Grub Bio Research GmbH). The indicated PE-conjugated anti-cytokine mAb was incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. After extensive washing, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages (5 × 104) were stimulated with THP (10 μg/ml), LPS (10 ng/ml), or CpG (10 μM) in 96-well plates (final volume 200 μl). Supernatants were harvested after 4 and 16 hours, and cytokines were measured by sandwich ELISA kits from R&D Systems Inc.

For MLC, stimulator cells were irradiated (30 Gy, 137Cs source) and added at increasing cell numbers to 105 allogeneic T cells in 96-well culture plates in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS (total volume 200 μl/well). After 5 days, cells were pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]-thymidine (ICN Pharmaceuticals Inc.). After another 18 hours, the cells were harvested on glass-fiber filters (Topcount; Packard Instrument Company) and DNA-associated radioactivity was determined using a microplate scintillation counter (Packard Instrument Company). DNA synthesis was expressed as mean counts per minute of triplicate cultures. Supernatants from the respective MLC were obtained 24 and 48 hours after culture initiation and analyzed for IL-2 and IFN-γ by ELISA (capture as well as detection Abs were obtained from R&D Systems Inc.). The lower detection limit for these cytokines was 20 pg/ml.

Biochemical analysis of signal-transduction events.

Immature DCs or mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages were stimulated with 30 μg/ml THP, 100 ng/ml LPS, or medium alone for 15–60 minutes. Activation was stopped by addition of ice-cold washing buffer (RPMI-1640). Cells were pelleted by short centrifugation (12,000 g for 20 seconds) and lysed on ice for 30 minutes in TBS, pH 7.4, containing 1% NP-40 (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.), phosphatase (1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM NaF, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 5 mM EDTA), and protease inhibitors. Nuclei were removed by short centrifugation; supernatants are referred to as whole-cell lysates. Proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond ECL; Amersham Biosciences). Abs against IRAK-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), Akt (BioVision Inc.), and ERK-2, p38, IκB-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) were used to detect the respective antigens. Protein phosphorylation was assessed using Abs directed against phosphorylated isoforms of Akt (BioVision Inc.), ERK-1/2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), and p38 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc.). Peroxidase-labeled secondary Abs (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.) were used to detect primary Ab binding. Chemiluminescence generated from enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) was detected on a Lumi-Imager (Roche Diagnostics GmbH) (48).

Clotting assay determination of TF activity.

HUVECs were seeded in 6-well plates at 80–90% confluence and grown overnight. Cells were scraped from the plates and analyzed for TF activity as described (49). HUVECs were left untreated or treated with 200 U/ml IFN-γ (R&D Systems Inc.) for 2 hours and then stimulated with LPS or THP at the indicated concentrations for 6 hours. The cells were washed twice and scraped in 1 ml clotting buffer (12 mM sodium acetate, 7 mM diethylbarbitate, and 130 mM sodium chloride; pH 7.4); 100 μl of resuspended cells were mixed with 100 μl of citrated plasma, and clotting times were measured after recalcification with 100 ml of 20 mM CaCl2 solution at 37°C. TF equivalents were determined using a standard curve obtained from rabbit brain thromboplastin.

EMSA.

Nuclear extracts from DCs were prepared as described (50, 51). Oligonucleotides resembling the consensus binding site for NF-κB (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) and CRE (5′-AGAGATTGCCTGACGTCAGAGAGCTAG-3′) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. The double-stranded oligonucleotides used in all experiments were end-labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ32P]-ATP. After labeling, 5 μg of nuclear extract was incubated with 120,000 cpm of labeled probe in the presence of 3 μg of poly(dI-dC) at room temperature for 30 minutes. This mixture was separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel in Tris/glycine/EDTA buffer at pH 8.5. Control experiments were performed as described (51). For control, competition experiments using unlabeled NF-κB or CRE oligonucleotides were performed.

Statistics.

Cytokine levels were compared using Student’s t tests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants (P14874-B08, to G.J. Zlabinger; P16788-B13, to T.M. Stulnig) from the Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung, Österreich, as well as by grants from the Center of Molecular Medicine (CeMM), a basic research institute within the companies of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (to T.M. Stulnig). Moreover, we are grateful to Wolfgang Zauner for synthesis of the TIRAP/Mal inhibitory peptide, and to Bianca Weissenhorn, Alessandra Mathe, and Margarethe Merio for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

G. Staffler’s and U. Ahsen’s present address is: Biovertis AG, Campus Vienna Biocenter 6, Vienna, Austria.

M.D. Saemann and T. Weichhart contributed equally to this work.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: EMSA, electrophoretic mobility shift assay; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; IRAK-1, IL-1 receptor–associated kinase 1; MLC, mixed lymphocyte culture; rh, recombinant human; TF, tissue factor; THP, Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Pulendran B, Palucka K, Banchereau J. Sensing pathogens and tuning immune responses. Science. 2001;293:253–256. doi: 10.1126/science.1062060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:335–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akira S, Takeda K, Kaisho T. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang D, et al. A toll-like receptor that prevents infection by uropathogenic bacteria. Science. 2004;303:1522–1526. doi: 10.1126/science.1094351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jouault T, et al. Candida albicans phospholipomannan is sensed through toll-like receptors. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;188:165–172. doi: 10.1086/375784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Canavera SJ, Akira S, Underhill DM. Collaborative induction of inflammatory responses by dectin-1 and Toll-like receptor 2. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:1107–1117. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown GD, et al. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta-glucans. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:1119–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamura Y, et al. The extra domain A of fibronectin activates Toll-like receptor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10229–10233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Termeer C, et al. Oligosaccharides of Hyaluronan activate dendritic cells via toll-like receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:99–111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biragyn A, et al. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of dendritic cells by beta-defensin 2. Science. 2002;298:1025–1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1075565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopp E, Medzhitov R. Recognition of microbial infection by Toll-like receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2003;15:396–401. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serafini-Cessi F, Malagolini N, Cavallone D. Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein: biology and clinical relevance. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003;42:658–676. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00829-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas DB, Davies M, Williams JD. Tamm-Horsfall protein: an aetiological agent in tubulointerstitial disease? Exp. Nephrol. 1993;1:281–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokot F, Dulawa J. Tamm-Horsfall protein updated. Nephron. 2000;85:97–102. doi: 10.1159/000045640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayrer AR, Miniter P, Andriole VT. Immunopathogenesis of chronic pyelonephritis. Am. J. Med. 1983;75:59–70. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan SR, Kok DJ. Modulators of urinary stone formation. Front. Biosci. 2004;9:1450–1482. doi: 10.2741/1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su SJ, Chang KL, Lin TM, Huang YH, Yeh TM. Uromodulin and Tamm-Horsfall protein induce human monocytes to secrete TNF and express tissue factor. J. Immunol. 1997;158:3449–3456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreft B, et al. Polarized expression of Tamm-Horsfall protein by renal tubular epithelial cells activates human granulocytes. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:2650–2656. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2650-2656.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mo L, et al. Ablation of the Tamm-Horsfall protein gene increases susceptibility of mice to bladder colonization by type 1-fimbriated Escherichia coli. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2004;286:F795–F802. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00357.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates JM, et al. Tamm-Horsfall protein knockout mice are more prone to urinary tract infection: rapid communication. Kidney Int. 2004;65:791–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstein SL, June CH, DeFranco AL. Lipopolysaccharide-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation in human macrophages is mediated by CD14. J. Immunol. 1993;151:3829–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontan E, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Briend E, Fauve RM. Purification of a 92 kDa human immunostimulating glycoprotein obtained from the Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein. J. Immunol. Methods. 1995;187:81–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(95)00169-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serafini-Cessi F, Bellabarba G, Malagolini N, Dall’Olio F. Rapid isolation of Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein (uromodulin) from human urine. J. Immunol. Methods. 1989;120:185–189. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90241-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ardeshna KM, Pizzey AR, Devereux S, Khwaja A. The PI3 kinase, p38 SAP kinase, and NF-kappaB signal transduction pathways are involved in the survival and maturation of lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;96:1039–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ouaaz F, Arron J, Zheng Y, Choi Y, Beg AA. Dendritic cell development and survival require distinct NF-kappaB subunits. Immunity. 2002;16:257–270. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssens S, Beyaert R. Functional diversity and regulation of different interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family members. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Horng T, Barton GM, Medzhitov R. TIRAP: an adapter molecule in the Toll signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:835–841. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lynn KL, et al. Antibodies to Tamm-Horsfall urinary glycoprotein in patients with urinary tract infection, reflux nephropathy, urinary obstruction and paraplegia. Contrib. Nephrol. 1984;39:296–304. doi: 10.1159/000409258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandberg T, Fasth A. Association between fever and the antibody response to Tamm-Horsfall protein in urinary tract infection. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. 1987;21:297–300. doi: 10.3109/00365598709180786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoyer JR. Tubulointerstitial immune complex nephritis in rats immunized with Tamm-Horsfall protein. Kidney Int. 1980;17:284–292. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayrer AR, et al. Tubulointerstitial nephritis and immunologic responses to Tamm-Horsfall protein in rabbits challenged with homologous urine or Tamm-Horsfall protein. J. Immunol. 1982;128:2634–2642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagai T. Tubulointerstitial nephritis by Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein or egg white component. Nephron. 1987;47:134–140. doi: 10.1159/000184476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fasth A, Hoyer JR, Seiler MW. Renal tubular immune complex formation in mice immunized with Tamm-Horsfall protein. Am. J. Pathol. 1986;125:555–562. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivanyi B, Marcussen N, Kemp E, Olsen TS. The distal nephron is preferentially infiltrated by inflammatory cells in acute interstitial nephritis. Virchows Arch., A, Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1992;420:37–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01605982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavallone D, Malagolini N, Serafini-Cessi F. Binding of human neutrophils to cell-surface anchored Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein in tubulointerstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1787–1799. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fowler JE, Jr, Lynes WL, Lau JL, Ghosh L, Mounzer A. Interstitial cystitis is associated with intraurothelial Tamm-Horsfall protein. J. Urol. 1988;140:1385–1389. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)42051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neal DE, Jr, Dilworth JP, Kaack MB. Tamm-Horsfall autoantibodies in interstitial cystitis. J. Urol. 1991;145:37–39. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marier R, et al. Antibody to Tamm-Horsfall protein in patients with urinary tract obstruction and vesicoureteral reflux. J. Infect. Dis. 1978;138:781–790. doi: 10.1093/infdis/138.6.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fasth A, Bengtsson U, Kaijser B, Wieslander J. Antibodies to Tamm-Horsfall protein associated with renal damage and urinary tract infections in adults. Kidney Int. 1981;20:500–504. doi: 10.1038/ki.1981.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fasth A, Bjure J, Hjalmas K, Jacobsson B, Jodal U. Serum autoantibodies to Tamm-Horsfall protein and their relation to renal damage and glomerular filtration rate in children with urinary tract malformations. Contrib. Nephrol. 1984;39:285–295. doi: 10.1159/000409257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen AH, Border WA, Rajfer J, Dumke A, Glassock RJ. Interstitial Tamm-Horsfall protein in rejecting renal allografts. Identification and morphologic pattern of injury. Lab. Invest. 1984;50:519–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang ZQ, Kirk KA, Connelly KG, Sanders PW. Bence Jones proteins bind to a common peptide segment of Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein to promote heterotypic aggregation. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:2975–2983. doi: 10.1172/JCI116920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berke ES, Mayrer AR, Miniter P, Andriole VT. Tubulointerstitial nephritis in rabbits challenged with homologous Tamm-Horsfall protein: the role of endotoxin. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1983;53:562–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamm I, Horsfall FL. A mucoprotein derived from human urine which reacts with influenza, mumps and Newcastle disease virus. J. Exp. Med. 1952;95:71–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.95.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pak J, Pu Y, Zhang ZT, Hasty DL, Wu XR. Tamm-Horsfall protein binds to type 1 fimbriated Escherichia coli and prevents E. coli from binding to uroplakin Ia and Ib receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:9924–9930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stöckl J, et al. Human major group rhinoviruses downmodulate the accessory function of monocytes by inducing IL-10. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:957–965. doi: 10.1172/JCI7255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeyda M, et al. Suppression of T cell signaling by polyunsaturated fatty acids: selectivity in inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor activation. J. Immunol. 2003;170:6033–6039. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mechtcheriakova D, et al. Specificity, diversity, and convergence in VEGF and TNF-alpha signaling events leading to tissue factor up-regulation via EGR-1 in endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2001;15:230–242. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0247com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saemann MD, et al. Bacterial metabolite interference with maturation of human monocyte- derived dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002;71:238–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stuhlmeier KM, Kao JJ, Bach FH. Arachidonic acid influences proinflammatory gene induction by stabilizing the inhibitor-kappaB-alpha/nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) complex, thus suppressing the nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24679–24683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]