Abstract

Background

Striae gravidarum (SG) are atrophic linear scars that represent one of the most common connective tissue changes during pregnancy. SG can cause emotional and psychological distress for many women. Research on risk factors, prevention, and management of SG has been often inconclusive.

Methods

We conducted a literature search using textbooks, PubMed, and Medline databases to assess research performed on the risk factors, prevention, and management of SG. The search included the following key words: striae gravidarum, pregnancy stretch marks, and pregnancy stretch. We also reviewed citations within articles to identify relevant sources.

Results

Younger age, maternal and family history of SG, increased pre-pregnancy and pre-delivery weight, and increased birth weight were the most significant risk factors identified for SG. Although few studies have confirmed effective prevention methods, Centella asiatica extract, hyaluronic acid, and daily massages showed some promise. Treatment for general striae has greatly improved over the last few years. Topical tretinoin ≥ 0.05% has demonstrated up to 47% improvement of SG and non-ablative fractional lasers have consistently demonstrated 50 to 75% improvement in treated lesions of striae distensae.

Conclusion

Overall, SG has seen a resurgence in research over the last few years with promising data being released. Results of recent studies provide dermatologists with new options for the many women who are affected by these disfiguring marks of pregnancy.

Keywords: Striae gravidarum, pregnancy, stretch marks, striae distensae

Introduction

Striae gravidarum (SG) is a common, disfiguring, gestational change that affects between 55% (Chang et al., 2004, Picard et al., 2015) and 90% (Fitzpatrick and Freedberg, 2003) of women (Ghasemi et al., 2007, Rathore et al., 2011). SG presents as atrophic linear scars and can cause distress, often leading to a decrease in quality of life (Korgavkar and Wang, 2015, Park and Murase, 2013). SG are often overlooked as a cosmetic concern, which does not make the patient burden any less. Current research on risk factors, prevention, and management of this condition has been limited or met with little success and/or provided conflicting results (Chang et al., 2004).

Throughout history, stretch marks have always been a source of distress for pregnant women. As early as 16 BC, the poet Ovid alluded to women who would self-abort their pregnancies to avoid stretch marks (Rayor and Batstone, 1995). Ancient Egyptians recorded numerous preparations for the treatment of stretch marks and Soranus and Pliny the Elder in the 1st Century AD endorsed unripe olive oil and sea salt, respectively (Owsei, 1991). Frankincense is one of the most often recommended treatments (NWI Trading Co., 2016). There has been an additional wide range of therapeutics from topical medications to surgical modalities proposed for stretch marks, which reinforces the concern that is associated with this condition.

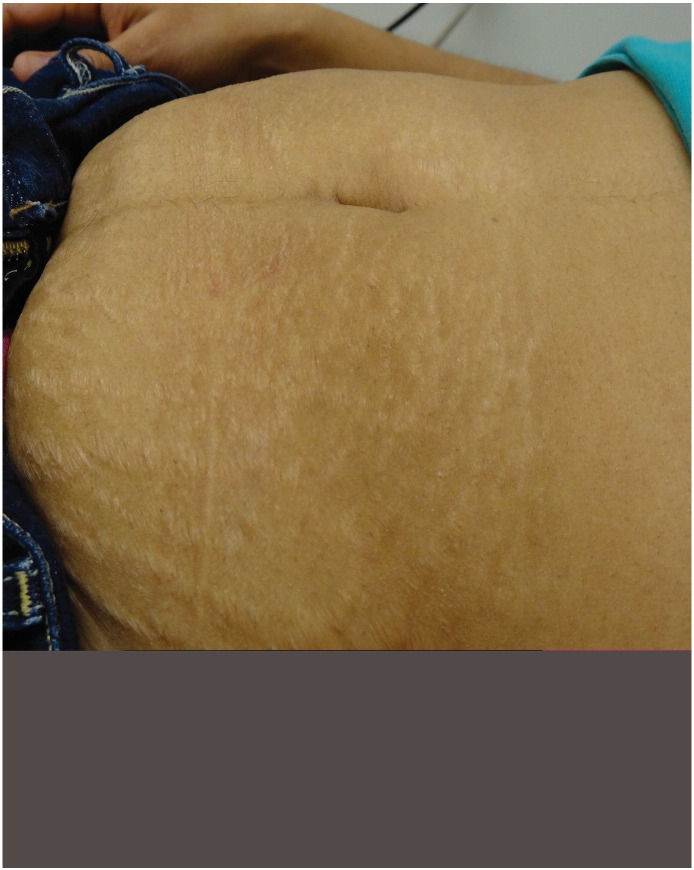

SG first present as flat, pink-to-red bands (striae rubra or immature striae) that become raised, longer, wider, and violet-red (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). Over a period of months to years, the marks fade and become hypopigmented (striae alba or mature striae), appearing parallel to skin tension lines as scar-like, wrinkled, white, and atrophic marks (Fig. 3; Salter and Kimball, 2006, Sodhi and Sausker, 1988, Watson et al., 1998). SG can cause itching, burning, and discomfort and typically present on the breasts, abdomen, hips, and thighs. Up to 90% of SG appear in primigravidas (Chang et al., 2004). Onset has typically been reported in the late second and early third trimester; however, one study has demonstrated that 43% of women develop SG prior to 24 weeks of gestation (Chang et al., 2004).

Fig. 1.

Immature striae (striae rubra) on the abdomen.

Fig. 2.

Striae rubra on the thigh.

Fig. 3.

Mature striae (striae alba) on the abdomen.

The etiopathogenesis involves a combination of genetic factors (Di Lernia et al., 2001), hormonal factors (Chang et al., 2004, Cordeiro et al., 2010, Lurie et al., 2011, Murphy et al., 1992), and increased mechanic stress on connective tissue (Fitzpatrick and Wolff, 2008, Ghasemi et al., 2007, Murphy et al., 1992, Watson et al., 1998). Interestingly, skin stretch has been a controversial trigger as studies have demonstrated an inconsistent association of SG with maternal weight gain and abdominal and hip girth stretch (Atwal et al., 2006, Chang et al., 2004, Poidevin, 1959). With regard to hormonal factors, twice as many estrogen receptors and elevated androgen and glucocorticoid receptors have been observed in striae compared with those in healthy skin (Cordeiro et al., 2010). Pregnancy’s distinct hormonal milieu is thought to influence connective tissue that is susceptible to SG when stretched. Ultimately, abnormalities in elastic fibers (Pinkus et al., 1966, Sheu et al., 1991, Tsuji and Sawabe, 1988), collagen fibrils (Pinkus et al., 1966, Shuster, 1979), and other extracellular membrane components (Watson et al., 1998) are believed to underlie the pathogenesis of SG (Wang et al., 2015).

Histologically, the appearance of SG is similar to striae distensae (SD) and contingent on lesion age. Early on, active lesions are comprised predominantly of fine elastic fibers but aging lesions demonstrate a thinning of the dermis and decrease of collagen content in the upper dermis (Watson et al., 1998). Biopsy tissue samples of SG show a disorganization, shortening, and thinning of the elastic fiber network compared with tissue samples of normal skin (Murphy et al., 1992, Wang et al., 2015). Although they are thin and disorganized, fibrils are tropoelastin-rich, which is likely due to uncoordinated synthesis (Wang et al., 2015). Light microscopy demonstrates a flattening of the epidermis with atrophy and loss of rete ridges and increased glycosaminoglycans (Murphy et al., 1992, Salter and Kimball, 2006, Watson et al., 1998). However, the severity and development of lesions varies among patients, which indicates a variable genetic predisposition.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted using textbooks and PubMed and MEDLINE databases to date to identify evidence-based data on the risk factors, prevention, and management of SG. Key search terms included striae gravidarum, pregnancy stretch marks, and pregnancy stretch. A literature search up to August 2016 revealed 28 articles available online that specifically studied SG, including cross-sectional, prospective, randomized controlled, and quasi-randomized controlled studies. The search was restricted to English-language articles with the exception of two articles that were translated from German. Table 1 provides a summary of studies that assessed risk factors of SG. Table 2 includes studies that assessed SG prevention methods. Table 3 shows studies that are relevant to SG treatments and treatment efficacy and their adverse events. In addition to the limited number of studies on the management of SG (Table 3), we incorporated a review of the most current treatments in use for nongestational SD, which may be used as a guide for future SG treatment.

Table 1.

Risk factors for striae gravidarum

| Investigators and Study Type | Number of Subjects and Subject profiles | Risk Factors Identified⁎ | Treatments |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Picard et al., 2015 Cross-sectional study |

800 primiparous ♀ examined postpartum with mean age of 26.3 |

|

Topical treatments to reduce the occurrence of SG were not found to be effective |

|

Kasielska-Trojan et al., 2015 Cross-sectional study |

299 Caucasian ♀ up to 6 mos after delivery, without distinguishing primiparous or multiparas. |

|

Progesterone treatment was not found to be related to SG |

|

J-Orh et al., 2008 Cross-sectional study |

280 Thai ♀ who had just given birth to first child, in the immediate postpartum period. |

|

Did not assess |

|

Osman et al., 2007 Cross-sectional study |

112 primiparous Lebanese ♀ assessed during the immediate postpartum period |

|

Did not assess |

|

Atwal et al., 2006 Cross-sectional study with questionnaire |

309 primiparous ♀ within 48 hours of delivery |

|

Did not assess |

|

Chang et al., 2004 Cross-sectional study with anonymous survey |

161 ♀ who had just given birth |

|

Did not assess |

|

Ersoy et al., 2016 Prospective observational study |

211 singleton primiparous pregnant ♀ who were hospitalized for birth and who did not have systemic diseases or other risk factors, like drug use or polyhydramnios. |

|

Use of preventive oil or drugs, did not affect development of SG |

|

Findik et al., 2011 Prospective study |

69 primigravidas using prophylactic iron and vitamin preparations at 36 wks gestation or greater |

|

Did not assess |

|

Thomas and Liston, 2004 Prospective observational study |

128 primigravid ♀ who presented in labor or for induction of labor |

|

Did not assess |

|

Davey, 1972 Prospective study |

76 primiparous ♀ |

|

SG were less common in skin messaged with olive oil |

|

Madlon-Kay, 1993 Retrospective cohort study |

48 nulliparous ♀ at 34 to 36 weeks' estimated gestational age |

|

♀ who used oils or creams formed striae as frequently as those who did not |

♀=women; BMI = body-mass index; mos = months; SG = striae gravidarum; yrs = years.

Statistical significance is defined as p ≤ 0.05

Table 2.

Prevention of striae gravidarum

| Investigators and Study Type | Number of Subjects and Subject Profiles | Preventive Methods Used | Results of Preventive Methods⁎ |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mallol et al., 1991 Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study |

80 pregnant ♀ during their first 12 weeks of a healthy pregnancy | Trofolastin cream with Centella asiatica extract, α-tocopherol and collagen–elastin hydrolysates; applied daily from 12th week of pregnancy until delivery |

|

|

García Hernández et al., 2013 Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study |

183 pregnant patients over age 18 at week 12 +/- 2 | Cream containing hydroxyprolisilane-C, rosehip oil, Centella asiatica triterpenes and vitamin E; applied twice a day around 12 weeks of pregnancy |

|

|

Taavoni et al., 2011 Randomized clinical study |

70 nulliparous ♀ aged between 20-30 yrs old, in 18–20th week of gestation with BMI ranging between 18.5-25. 35 used treatment, 35 did not | Olive oil applied topically onto abdomen twice daily, without massaging, vs. no olive oil |

|

|

Soltanipoor et al., 2012 Randomized controlled clinical study |

100 nulliparous pregnant ♀; 50 used treatment, 50 did not | Olive oil applied topically onto abdomen twice daily, without massaging, vs. no olive oil |

|

|

de Buman et al., 1987 Randomized controlled study |

90 pregnant ♀; 30 received treatment cream, 30 received vitamin cream, 30 received placebo | Alphastria cream (hyaluronic acid, allantoin, vitamin A, vitamin E and calcium pantothenate) vs. vitamin cream vs. placebo cream; messaged for a few minutes daily to the thighs, abdomen and chest, starting at the 3rd month of pregnancy and ending 3 mos after childbirth |

|

|

Wierrani et al., 1992 Randomized controlled study |

50 pregnant ♀; 24 received treatment, 26 did not receive any treatment | Verum cream (vitamin E, essential fatty acids, panthenol, hyaluronic acid, elastin and menthol); massaged onto the abdomen, thighs and breasts starting at the 20th week of pregnancy |

|

|

Soltanipour et al., 2014 Parallel randomized controlled clinical study |

150 nulliparous ♀ at their second trimester of pregnancy in Iran. 50 subjects in each group | Olive oil vs. Saj® cream that contains lanolin, stearin, triethanolamine, almond oil, and bizovax glycerin amidine vs. placebo |

|

|

Osman et al., 2008 Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study |

175 nulliparous ♀ in Lebanon with singleton pregnancies between week 12 and 18 weeks of gestation. 91 with study treatment, 84 with placebo | Cocoa butter lotion vs. placebo lotion, daily from weeks 12-18 |

|

|

Buchanan et al., 2010 Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study |

300 pregnant ♀; 150 received treatment, 150 placebo | Cocoa butter lotion vs. placebo lotion, daily from 16 weeks to delivery |

|

|

Timur Taşhan and Kafkasli, 2012 Posttest-only quasi-experimental design with a control group |

141 primiparous ♀ who visited the pregnancy unit in Turkey between February 1st, 2010 and April 15th, 2011. 47 subjects in oil + massage, 48 in oil – massage, 46 in control | Bitter almond oil applied with or without massage vs. control; applied every other day in weeks 19–32 of pregnancy, followed by daily until delivery |

|

|

Poidevin, 1959 Prospective study |

116 primigravidas;♀ 55 used treatment, 66 did not | Olive oil vs. no olive oil applied daily |

|

|

Davey, 1972 Prospective study |

76 primiparous ♀; 35 used treatment, 41 did not | Olive oil massaged into abdomen daily vs. no olive oil |

|

♀=women; BMI = body-mass index; mos = months; SG = striae gravidarum; yrs = years.

Statistical significance is defined as p ≤ 0.05

Table 3.

Treatment of striae gravidarum

| Investigators and Study Type | Number of Subjects and Subject Profiles | Type of Striae | Treatment | Efficacy⁎ | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Malekzad et al., 2014 Prospective pilot study |

10 ♀ aged 26-50, Fitzpatrick skin types III-V | Striae alba | 1540-nm non-ablative fractional laser |

|

Mild post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation in one patient after 8-week treatment and mild acne in another patient after 4 weeks of treatment |

|

Rangel et al., 2001 Open-label, multicenter, prospective study |

26 ♀ with abdominal pregnancy-related striae | Not reported | 0.1% tretinoin cream daily for 3 mos applied to SG |

|

Erythema and scaling were the most common adverse events |

|

Pribanich et al., 1994 Double-blind placebo controlled study |

11 non-pregnant ♀ who had SG, 6 received treatment and 5 placebo | Not reported | 0.025% tretinoin cream applied daily for 7 mos |

|

Did not assess |

|

Kang et al., 1996 Double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study |

22 healthy white ♀ with erythematous stretch marks, 10 received treatment and 12 vehicle | Striae rubra | 0.1% tretinoin (n = 10) or vehicle (n = 12) daily for 6 mos to the affected areas |

|

Erythema and scaling, with itching and burning |

|

Ash et al., 1998 Randomized controlled study |

10 American nonpregnant ♀ of varying skin types, age 23 to 49 yr. Striae age ranged from 8 mos to 31 yr and all were white striae. All patients had abdominal striae, 50% also had striae on thighs |

Striae alba | 20% glycolic acid + 0.05% tretinoin vs. 20% glycolic acid + 10% ascorbic acid, applied daily to abdomen or thighs for 12 weeks (each regimen was applied to half the treatment area) |

|

70% of patients experienced mild irritation at treatment initiation on both treatment sites. A single patient developed a mild irritant dermatitis |

♀=women; mos = months; SG = striae gravidarum; yrs = years.

Statistical significance is defined as p ≤ 0.05

Results

Risk factors

The most common risk factors for SG include younger age, maternal and family history of SG, higher pre-pregnancy and pre-delivery weight, and higher birth weight (Table 1). Most studies showed a statistically significant association between these risk factors and SG, although Findik et al. (2011) and Chang et al. (2004) did not confirm pre-pregnancy weight or maternal age as a risk factor. Most studies also demonstrated that a history of striae on the breasts, hips, and thighs was associated with formation of SG; however, a study of 299 Caucasian women showed that although striae on the breasts increased risk of SG, striae on the thighs decreased the risk of SG. The study by Chang et al. (2004) found a higher prevalence of SG in non-white women. With regard to socioeconomic status, multiple studies showed that unemployment, receiving state medical assistance, and lower education level were also associated with SG. However, confounding factors should be considered. Increased alcohol intake, decreased water consumption, decreased blood vitamin C levels, and expecting a male baby were also found to be more common among those women who developed SG in select studies. Even though it has been speculated that diabetes and increased serum glucose levels could play a part in the pathogenesis of SG, the studies included here did not reveal an association with diabetes or glycosylated hemoglobin levels. Studies were limited by study type, size, and patient population.

Prevention

Preventative treatments have met with limited success. Creams that contain Centella asiatica extract, especially Trofolastin cream, are best supported by data for the prevention or reduction of the severity of SG (Table 2; García Hernández et al., 2013, Mallol et al., 1991). Centella asiatica is a medicinal herb that is thought to increase the production of collagen and elastic fibers (García Hernández et al., 2013). Mallol et al. (1991) demonstrated that Trofolastin cream with Centella asiatica extract, α-tocopherol, and collagen–elastin hydrolysates that is applied daily from gestational week 12 until delivery significantly reduced the incidence of SG compared with placebo. Both Mallol et al. (1991) and García Hernández et al. (2013) found that creams that contained Centella asiatica significantly reduced the intensity and/or severity of SG among women who did develop SG. García Hernández et al. (2013) also demonstrated that the severity of previous striae significantly increased in the patient group treated with placebo but did not change in the patient group treated with Centella cream.

The application of almond oil, olive oil, or cocoa butter consistently failed to significantly lower the incidence of SG compared with placebo group. Two studies did find that when olive oil or almond oil were applied with a massage daily, they were associated with a lower incidence of SG development. However, these results may reflect the benefits of massage alone (Davey, 1972, Timur Taşhan and Kafkasli, 2012).

Alphastria cream and verum cream, two proprietary creams that contain hyaluronic acid combined with various vitamins and fatty acids, were shown to significantly lower the incidence of SG in two studies (de Buman et al., 1987, Wierrani et al., 1992). Hyaluronic acid, the active ingredient in both creams, is thought to increase resistance to mechanical forces and oppose atrophy through stimulation of fibroblast activity and collagen production (Elsaie et al., 2009, Korgavkar and Wang, 2015). In both studies, the creams were applied through massage during the second trimester, which poses the question of whether the creams were truly beneficial or whether the results reflected the benefits of massage alone.

Management

Although many studies that utilize topical medications or lasers for the treatment of nongestational SD have been performed, only a limited number of these studies focused specifically on SG treatment. Treatment should be instituted during the early stages of SG rather than when striae have matured and permanent changes have occurred. Many homeopathic and alternative therapies, including fruit and vegetable oils that hydrate the skin, are employed but limited by insufficient evidence.

Topical medications

Tretinoin cream and a combination of 20% glycolic acid + 10% ascorbic acid were shown to improve SG in clinical studies (Table 3). Use of tretinoin 0.05% and 0.1% creams on a daily basis for 3 to 7 months consistently resulted in overall global improvement of SG up to 47% (Ash et al., 1998), and decreased in mean length and width up to 20% and 23% respectively (Rangel et al., 2001), of lesions. A study by Pribanich et al. (1994) showed that the minimum effective concentration of tretinoin cream is 0.05%. Twenty percent glycolic acid combined with either 10% ascorbic acid or 0.05% tretinoin improved the appearance of SG although there was no statistically significant difference between the two combinations (Ash et al., 1998). Tretinoin increased elastin content in the papillary and reticular dermis of the lesions but ascorbic acid and untreated areas did not show such improvement. Both treatments increased epidermal thickness and decreased papillary dermal thickness in SG lesions.

Laser treatments

A 1540-nm non-ablative fractional laser demonstrated a statistically-significant clinical improvement in SG that ranged from 1 to 24% and an observable difference at 3 months post-treatment (Malekzad et al., 2014). For nongestational SD, both fractional and non-fractional lasers have been employed with varying efficacies.

Among fractional lasers, both non-ablative Erbium (Er):Glass and ablative carbon dioxide (CO2) lasers have been studied. An average of 50 to 75% improvement in lesions after 2 to 6 nonablative Er:Glass treatments has been reported (Bak et al., 2009, de Angelis et al., 2011, Tretti Clementoni and Lavagno, 2015). Histologic studies showed an increase in elastic fibers and collagen production. This laser was generally safe and treatments were well-tolerated by patients. In a study by Lee et al. (2010), ablative CO2 lasers were demonstrated to have improvements of 50 to 75%, especially in striae alba. However, other studies have shown inconsistent results (Cho et al., 2010). CO2 lasers are more painful and may have longer recovery times than non-ablative lasers.

Among non-fractional lasers, excimer, pulsed dye, neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG), copper bromide, and diode have been studied in the treatment of patients with nongestational SD. The excimer 308-nm laser is used to treat mature striae alba by producing repigmentation and has achieved up to 75% increase in pigmentation; however, results are generally temporary and pigmentation of the normal surrounding skin is an unfavorable consequence (Goldberg et al., 2003). Pulsed dye laser results in textural improvements but has shown a limited benefit to treat striae alba (McDaniel et al., 1996). It may be beneficial in striae rubra by reducing erythema (Aldahan et al., 2016). Nd:YAG laser, also a vascular laser, demonstrated excellent improvement of up to 70% or more, even though it is specifically for immature striae rubra (Goldman et al., 2008). Thirteen of 15 women experienced a complete resolution or modest improvement of striae for up to 2 years in a small study that used copper bromide laser (Longo et al., 2003). The diode laser was used to treat SD in dark-skinned individuals but this laser was ineffective and 64% of patients developed undesirable hyperpigmentation (Tay et al., 2006).

Light treatments

Light therapy modalities such as intense pulsed light (IPL), ultraviolet (UV) light, and infrared light have been employed for the treatment of nongestational SD. IPL seems to result in at least moderate improvement of striae (Al-Dhalimi and Abo Nasyria, 2013), but persistent erythema and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation may complicate this treatment. UV light, especially a combination of UV-B and UV-A, has been shown to consistently repigment striae alba. However, the results are not permanent and maintenance treatment is required (Sadick et al., 2007). Infrared light at 800 to 1800 nm can result in 25 to 50% improvement in striae alba after only four treatment sessions (Trelles et al., 2008). Long-term studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm these results.

Other modalities

Bipolar radiofrequency demonstrated clinical and histologic improvements in SD (Montesi et al., 2007), while tripolar third generation radiofrequency (Tripollar) resulted in 25 to 75% improvement at 1 week post-final treatment (Manuskiatti et al., 2009). Modalities such as microdermabrasion and microneedling have been found to be effective to improve nongestational striae in multiple studies. Microdermabrasion has been especially effective for striae rubra (Abdel-Latif and Elbendary, 2008). Microdermabrasion involves the blowing and subsequent vacuuming of abrasive substances to a treated area. Another study found that although microdermabrasion with sonophoresis improved striae, needling therapy yielded an even greater, statistically-significant improvement in striae compared with microdermabrasion (Nassar et al., 2016). Needling therapy causes controlled skin injury with the goal of producing new collagen and elastin in the papillary dermis.

Discussion

Stretch marks of pregnancy, which most commonly occur on the abdomen, breasts, hips, and thighs, have notably been a cause of distress and concern for the patient. Although many attempts have been made to identify risk factors, prevention methods, and treatments, a limited number of well-conducted, randomized controlled studies exist to date. This systematic review found that more studies addressed risk factors and prevention methods for SG than they did treatments specifically for SG and many more studies evaluated treatments for nongestational SD.

The most significant risk factors identified in this review are younger age, maternal and family history of SG, increased pre-pregnancy and pre-delivery weight, and increased birth weight. For prevention of SG, creams with Centella asiatica extract such as Trofolastin cream and a daily massage seem the most supported treatment options by the literature, but further studies are necessary. This information can be helpful for future expectant mothers who would like to try preventative treatments for SG. With regard to the management of SG, the current most effective therapies include tretinoin cream ≥ 0.05% and modalities such as nonablative fractional lasers. Laser treatment appears to yield on average greater mean improvement and in a much shorter time than topical treatments, but no head-to-head studies have been conducted to date. Tretinoin cream and laser treatments resulted in increased elastin content and collagen production in the treated lesions, which can partly explain the improvement observed. Many new studies that test novel laser treatments, microdermabrasion, and microneedling are underway.

Study limitations may explain the conflicting results in some studies. For example, some studies observed pre-pregnancy weight as a significant risk factor (Picard et al., 2015), but other studies did not view this but rather a genetic component as the most significant risk factor (Chang et al., 2004). The available studies often include a small and non-randomized sample size, especially those studies that are relevant to treatment. Additionally, studies do not always indicate the types of striae that are treated. Many more studies have been conducted for nongestational SD, which brings up the concern of whether these results may be extrapolated to SG.

SG are commonly regarded as a cosmetic nuisance and overlooked by practitioners as clinically insignificant. Skindex-29 is a validated questionnaire on the quality of life of patients with dermatologic conditions that has been used to assess total impairment caused by SG. The questionnaire focuses on three scales: emotion (psychological effects), symptoms, and daily functioning. In a study by Yamaguchi et al. (2012) to evaluate the quality of life of women with SG through the Skindex-29 questionnaire, the authors observed significantly greater psychological and/or emotional impairment among pregnant women with SG compared with women without SG (Yamaguchi et al., 2012). Using the same questionnaire, they also noted that pregnant women with severe SG scored significantly higher in areas of psychological and/or emotional impairment as well as daily functioning impairment, compared with those without SG and those with mild SG.

Conclusion

Striae gravidarum are a common form of gestational change that can be a substantial source of distress. Despite the identification of risk factors, prevention of SG remains challenging. Various therapies have been used to improve the appearance of SG. Fractional lasers and topical medications have yielded promising results. Further results from large, randomized-controlled studies are required to validate prevention and treatment options and their long-term efficacy data.

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors and all those who are qualified to be authors are listed in the author byline. There were no funding sources for this manuscript. To the best of our knowledge, no conflict of interest, financial or other, exists. This manuscript has not been previously published and is not under consideration in the same or substantially similar form in any other peer-reviewed media.

References

- Abdel-Latif A.M., Elbendary A. Treatment of striae distensae with microdermabrasion: A clinical and molecular study. J Egypt Wom Dermatol Soc. 2008;5:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Aldahan A.S., Shah V.V., Mlacker S., Samarkandy S., Alsaidan M., Nouri K. Laser and light treatments for striae distensae: A comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:239–256. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dhalimi M.A., Abo Nasyria A.A. A comparative study of the effectiveness of intense pulsed light wavelengths (650 nm vs 590 nm) in the treatment of striae distensae. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2013;15:120–125. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2012.748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ash K., Lord J., Zukowski M., McDaniel D.H. Comparison of topical therapy for striae alba (20% glycolic acid/0.05% tretinoin versus 20% glycolic acid/10% L-ascorbic acid) Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:849–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwal G.S., Manku L.K., Griffiths C.E., Polson D.W. Striae gravidarum in primiparae. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:965–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak H., Kim B.J., Lee W.J., Bang J.S., Lee S.Y., Choi J.H. Treatment of striae distensae with fractional photothermolysis. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1215–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan K., Fletcher H.M., Reid M. Prevention of striae gravidarum with cocoa butter cream. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2010;108:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A.L., Agredano Y.Z., Kimball A.B. Risk factors associated with striae gravidarum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:881–885. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S.B., Lee S.J., Lee J.E., Kang J.M., Kim Y.K., Oh S.H. Treatment of striae alba using the 10,600-nm carbon dioxide fractional laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:118–119. doi: 10.3109/14764171003706117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro R.C., Zecchin K.G., de Moraes A.M. Expression of estrogen, androgen, and glucocorticoid receptors in recent striae distensae. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:30–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.04005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey C.M. Factors associated with the occurrence of striae gravidarum. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1972;79:1113–1114. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1972.tb11896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Angelis F., Kolesnikova L., Renato F., Liguori G. Fractional nonablative 1540-nm laser treatment of striae distensae in Fitzpatrick skin types II to IV: Clinical and histological results. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:411–419. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11402493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Buman M., Walther M., de Weck R. Effectiveness of Alphastria cream in the prevention of pregnancy stretch marks (striae distensae). Results of a double-blind study. Gynakol Rundsch. 1987;27:79–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lernia V., Bonci A., Cattania M., Bisighini G. Striae distensae (rubrae) in monozygotic twins. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:261–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018003261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsaie M.L., Baumann L.S., Elsaaiee L.T. Striae distensae (stretch marks) and different modalities of therapy: An update. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:563–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersoy E., Ersoy A.O., Yasar Celik E., Tokmak A., Ozler S., Tasci Y. Is it possible to prevent striae gravidarum? J Chin Med Assoc. 2016;79:272–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findik R.B., Hascelik N.K., Akin K.O., Unluer A.N., Karakaya J. Striae gravidarum, vitamin C and other related factors. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2011;81:43–48. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick T.B., Freedberg I.M. 6th ed. McGraw-Hill Professional; New York: 2003. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in clinical medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick T.B., Wolff K. McGraw-Hill Medical; New York: 2008. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. [Google Scholar]

- García Hernández J.Á., Madera González D., Padilla Castillo M., Figueras F.T. Use of a specific anti-stretch mark cream for preventing or reducing the severity of striae gravidarum. Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2013;35:233–237. doi: 10.1111/ics.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi A., Gorouhi F., Rashighi-Firoozabadi M., Jafarian S., Firooz A. Striae gravidarum: Associated factors. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:743–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D.J., Sarradet D., Hussain M. 308-nm Excimer laser treatment of mature hypopigmented striae. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:596–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29144.x. discussion 598–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman A., Rossato F., Prati C. Stretch marks: treatment using the 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:686–691. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34129.x. discussion 691–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J-Orh R., Titapant V., Chuenwattana P., Tontisirin P. Prevalence and associate factors for striae gravidarum. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:445–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S., Kim K.J., Griffiths C.E., Wong T.Y., Talwar H.S., Fisher G.J. Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) improves early stretch marks. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:519–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasielska-Trojan A., Sobczak M., Antoszweski B. Risk factors of striae gravidarum. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2015;37:236–240. doi: 10.1111/ics.12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korgavkar K., Wang F. Stretch marks during pregnancy: a review of topical prevention. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:606–615. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.E., Kim J.H., Lee S.J., Lee J.E., Kang J.M., Kim Y.K. Treatment of striae distensae using an ablative 10,600-nm carbon dioxide fractional laser: A retrospective review of 27 participants. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1683–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo L., Postiglione M.G., Marangoni O., Melato M. Two-year follow-up results of copper bromide laser treatment of striae. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2003;21:157–160. doi: 10.1089/104454703321895617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lurie S., Matas Z., Fux A., Golan A., Sadan O. Association of serum relaxin with striae gravidarum in pregnant women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283:219–222. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K.W., Dunphy B., O’herlihy C. Increased maternal age protects against striae gravidarum. J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;12:297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Madlon-Kay D.J. Striae gravidarum. Folklore and fact. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2:507–511. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malekzad F., Shakoei S., Ayatollahi A., Hejazi S. The safety and efficacy of the 1540nm non-ablative fractional XD probe of star lux 500 device in the treatment of striae alba: Before-after study. J Lasers Med Sci. 2014;5:194–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallol J., Belda M.A., Costa D., Noval A., Sola M. Prophylaxis of Striae gravidarum with a topical formulation. A double blind trial. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1991;13:51–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.1991.tb00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuskiatti W., Boonthaweeyuwat E., Varothai S. Treatment of striae distensae with a TriPollar radiofrequency device: A pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:359–364. doi: 10.3109/09546630903085278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel D.H., Ash K., Zukowski M. Treatment of stretch marks with the 585-nm flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:332–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesi G., Calvieri S., Balzani A., Gold M.H. Bipolar radiofrequency in the treatment of dermatologic imperfections: Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical aspects. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:890–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar A., Ghomey S., El Gohary Y., El-Desoky F. Treatment of striae distensae with needling therapy versus microdermabrasion with sonophoresis. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2016;18:330–334. doi: 10.1080/14764172.2016.1175633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NWI Trading Co Frank-Incense - Frankincense resin and Frankincense Essential Oil [Internet] 2016. http://www.frank-incense.com [cited 2016 November 2]. Available from:

- Osman H., Rubeiz N., Tamim H., Nassar A.H. Risk factors for the development of striae gravidarum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:62.e1–62.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman H., Usta I.M., Rubeiz N., Abu-Rustum R., Charara I., Nassar A.H. Cocoa butter lotion for prevention of striae gravidarum: A double-blind, randomised and placebo-controlled trial. BJOG. 2008;115:1138–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owsei T. John Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1991. Soranus' Gynecology. [Google Scholar]

- Park K.K., Murase J.E. Connective Tissue Changes. In: Kroumpouzos G., editor. Har/Psc ed. Vol 1. LWW; 2013. (Text Atlas of Obstetric Dermatology). [Google Scholar]

- Picard D., Sellier S., Houivet E., Marpeau L., Fournet P., Thobois B. Incidence and risk factors for striae gravidarum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:699–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkus H., Keech M.K., Mehregan A.H. Histopathology of striae distensae, with special reference to striae and wound healing in the Marfan syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 1966;46:283–292. doi: 10.1038/jid.1966.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poidevin L.O. Striae gravidarum. Their relation to adrenal cortical hyperfunction. Lancet. 1959;2:436–439. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(59)90421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pribanich S., Simpson F.G., Held B., Yarbrough C.L., White S.N. Low-dose tretinoin does not improve striae distensae: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cutis. 1994;54:121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel O., Arias I., García E., Lopez-Padilla S. Topical tretinoin 0.1% for pregnancy-related abdominal striae: an open-label, multicenter, prospective study. Adv Ther. 2001;18:181–186. doi: 10.1007/BF02850112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore S.P., Gupta S., Gupta V. Pattern and prevalence of physiological cutaneous changes in pregnancy: A study of 2000 antenatal women. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:402. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.79741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayor D.J., Batstone W.W. Garland; New York: 1995. Latin lyric and elegiac poetry: An anthology of new translations. [Google Scholar]

- Sadick N.S., Magro C., Hoenig A. Prospective clinical and histological study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a targeted high-intensity narrow band UVB/UVA1 therapy for striae alba. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9:79–83. doi: 10.1080/14764170701313767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter S.A., Kimball A.B. Striae gravidarum. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu H.M., Yu H.S., Chang C.H. Mast cell degranulation and elastolysis in the early stage of striae distensae. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:410–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1991.tb01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster S. The cause of striae distensae. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1979;59:161–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi V.K., Sausker W.F. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltanipoor F., Delaram M., Taavoni S., Haghani H. The effect of olive oil on prevention of striae gravidarum: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20:263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltanipour F., Delaram M., Taavoni S., Haghani H. The effect of olive oil and the Saj® cream in prevention of striae gravidarum: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taavoni S., Soltanipour F., Haghani H., Ansarian H., Kheirkhah M. Effects of olive oil on striae gravidarum in the second trimester of pregnancy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2011;17:167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay Y.K., Kwok C., Tan E. Non-ablative 1,450-nm diode laser treatment of striae distensae. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:196–199. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R.G., Liston W.A. Clinical associations of striae gravidarum. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:270–271. doi: 10.1080/014436104101001660779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timur Taşhan S., Kafkasli A. The effect of bitter almond oil and massaging on striae gravidarum in primiparous women. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:1570–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trelles M.A., Levy J.L., Ghersetich I. Effects achieved on stretch marks by a nonfractional broadband infrared light system treatment. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:523–530. doi: 10.1007/s00266-008-9115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tretti Clementoni M., Lavagno R. A novel 1565 nm non-ablative fractional device for stretch marks: A preliminary report. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2015;17:148–155. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2015.1007061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji T., Sawabe M. Elastic fibers in striae distensae. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Calderone K., Smith N.R., Do T.T., Helfrich Y.R., Johnson T.R. Marked disruption and aberrant regulation of elastic fibres in early striae gravidarum. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1420–1430. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson R.E., Parry E.J., Humphries J.D., Jones C.J., Polson D.W., Kielty C.M. Fibrillin microfibrils are reduced in skin exhibiting striae distensae. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:931–937. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierrani F., Kozak W., Schramm W., Grünberger W. Attempt of preventive treatment of striae gravidarum using preventive massage ointment administration. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1992;104:42–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K., Suganuma N., Ohashi K. Quality of life evaluation in Japanese pregnant women with striae gravidarum: A cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:450. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]