Abstract

Candida glabrata is an increasingly important cause of invasive candidiasis. In China, relatively little is known of the molecular epidemiology of C. glabrata and of its antifungal susceptibility patterns. Here we studied 411 non-duplicate C. glabrata isolates from 411 patients at 11 hospitals participating in the National China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net program (CHIF-NET; 2010-2014). Genotyping was performed using multilocus sequence typing (MLST) employing six genetic loci and by microsatellite analysis. Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed using Sensititre YeastOne™ YO10 methodology. Of 411 isolates, 35 sequence types (ST) were identified by MLST and 79 different genotypes by microsatellite typing; the latter had higher discriminatory power than MLST in the molecular typing of C. glabrata. Using MLST, ST7 and ST3 were the most common STs (66.4 and 9.5% of all isolates, respectively) with 24 novel STs identified; the most common microsatellite types were T25 (30.4% of all isolates) and T31 (12.4%). Resistance to fluconazole (MIC > 32 μg/mL) was seen in 16.5% (68/411) of isolates whilst MICs of >0.5 μg/mL for voriconazole, >2 μg/mL for itraconazole and >2 μg/mL for posaconazole were seen for 28.7, 6.8, and 7.3% of isolates, respectively; 14.8% of all isolates cross-resistant/non-wide-type to fluconazole and voriconazole. Fluconazole resistant rates increased 3-fold over the 5-year period whilst that of isolates with non-WT MICs to voriconazole, 7-fold. All echinocandins exhibited >99% susceptibility rates against all isolates but notably one isolate exhibited multi-drug resistance to the azoles and echinocandins. The study has provided a global picture of the molecular epidemiology and drug resistance rates of C. glabrata in China during the period of the study.

Keywords: Candida glabrata, multilocus sequence typing (MLST), microsatellite genotyping, antifungal susceptibility, China

Introduction

Candida species are the most common opportunistic fungal pathogens in debilitated or immunecompromised hosts with high rates of mortality (up to 40%) (Hajjeh et al., 2004; Wisplinghoff et al., 2004; Kullberg and Arendrup, 2015; Pappas et al., 2016). Although the majority of cases of invasive candidiasis (IC) are attributed to Candida albicans, globally, there are increasing rates of infection by non-C. albicans species (Kullberg and Arendrup, 2015; Xiao et al., 2015; Pappas et al., 2016). The prevalence of Candida glabrata infections, in particular, has increased in the last decade, and this species is now the second most common cause of candidemia in the USA, accounting for up to one-third of cases of fungemia (Pfaller et al., 2001; Guinea, 2014). Data from the China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net (CHIF-NET) study have indicated that C. glabrata species complex was the third most common non-C. albicans species in China (Wang et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2015).

Candida glabrata complex comprises C. glabrata sensu stricto but also encompasses the cryptic species Candida bracarensis and Candida nivariensis (Hou et al., 2017). Yet within C. glarbata sensus strcito per se, intra-species delineation is useful, not only for molecular epidemiological studies but for investigation of biological niches and determining the route of infection transmission. Several molecular typing methods, e.g., pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), multilocus sequence typing (MLST) assays and microsatellite analysis have been established to determine genetic relatedness of C. glabrata (Dodgson et al., 2003; Foulet et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2007; Brisse et al., 2009; Enache-Angoulvant et al., 2010; Abbes et al., 2012). Of these, MLST is a highly discriminatory tool that can be standardized to allow objective comparison of results between centers. The use of a set of six gene fragments of C. glabrata (FKS, LEU2, NMT1, TRP1, UGP1, and URA3) is recommended (http://cglabrata.mlst.net/) (Dodgson et al., 2003). Microsatellite marker analysis is another rapid, reliable technique with several multilocus microsatellite systems proposed (Foulet et al., 2005; Brisse et al., 2009; Enache-Angoulvant et al., 2010; Abbes et al., 2012).

Data on the susceptibilities to antifungal agents are also important to guide best practice empirical antifungal therapy in patients with suspected C. glabrata IC (Yapar, 2014). C. glabrata is known to exhibit reduced susceptibility or resistance to fluconazole and the other azoles (Pfaller et al., 2004; Delliere et al., 2016). Further, resistance to the echinocandins (up to 10% in some centers), as well as of echinocandin and azole co-resistance is of growing concern in the USA (Pfaller et al., 2012; Alexander et al., 2013; Pham et al., 2014). In Europe, the prevalence of echinocandin resistance amongst C. glabrata isolates is low (<3%) (Delliere et al., 2016). In China, data on azole and echinocandin resistance are relatively sparse (Xiao et al., 2015).

In the present study, we investigated the nationwide molecular epidemiology and in vitro antifungal susceptibility of C. glabrata sensu stricto isolates causing IC in China during 2010–2014. In this study, MLST genotyping as well microsatellite analysis techniques were employed given their high discriminatory utility.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (No. S-263). Written informed consent were obtained from all patients in the study for permission to study the isolates cultured from them for scientific research.

Yeast isolates and identification

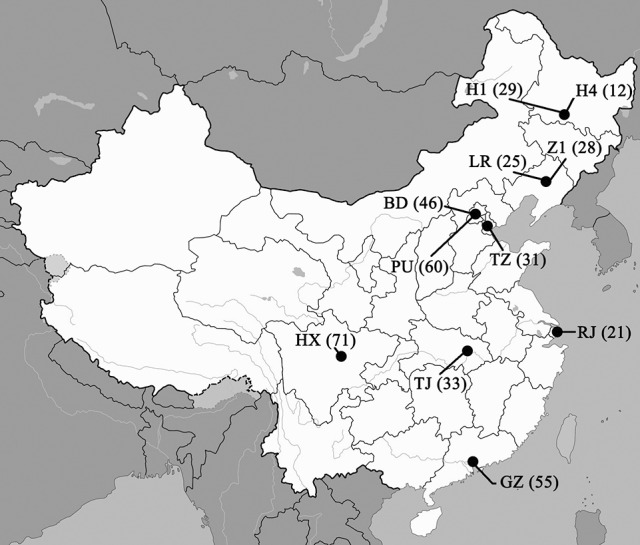

Candida glabrata isolates were collected prospectively over the 5-year study period from patients enrolled in the CHIF-NET study, a laboratory-based, national multicenter surveillance program conducted during August 2009 to July 2014. Only unique isolates i.e., only one strain per patient, were studied (Wang et al., 2012). A total of 411 clinical isolates from 411 patients in 11 hospitals (eight provinces) across China were analyzed (Figure 1, see Acknowledgments for participating hospitals). Isolates were identified as C. glabrata by a previously-established algorithm incorporating matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) (Vitek MS, bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) supplemented with rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequencing (Zhang et al., 2014). Only C. glabrata sensu stricto isolates were studied and the confidence value of Vitek MS was ≥90%. For each isolate, a minimum of five colonies were picked from a pure culture together and stored at −80°C in separate vials until use. Early experiments showed that the MLST and microsatellite results were identical for each of these five colonies (data not shown) and previous study described mixture of genotype in one out of 101 (1/101, 1%) isolates (Delliere et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the 11 study centers involved in this study and number of isolates collected in each center (shown in brackets). Hospital codes: BD, Peking University First Hospital; GZ, The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University; H1, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University; H4, the Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University; HX, West China Hospital; LR, The People's Hospital of Liaoning Province; PU, Peking Union Medical College Hospital; RJ, Ruijin Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University; TJ, Tongji Hospital; TZ, Tianjin Medical University General Hospital; Z1, The First Hospital of China Medical University.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST)

Total DNA was extracted from pure cultures as described previously (Wang et al., 2012). Briefly, six housekeeping gene loci (FKS, LEU2, NMT1, TRP1, UGP1, and URA3) were studied (Dodgson et al., 2003). The PCR products were sequenced in both directions using the DNA analyzer ABI 3730XL system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Nucleotide sequences were analyzed manually to ensure high quality sequences, and then queried against the C. glabrata MLST database (http://cglabrata.mlst.net) to assign alleles for each locus. The sequence type (ST) was then defined according to isolates' allelic profiles. Novel allele types in each novel ST were confirmed twice by sequencing in both directions.

Microsatellite analysis

Yeast isolates were genotyped using six highly polymorphic microsatellite markers namely RPM2, ERG3, MTI, GLM4, GLM5, and GLM6, chosen for their high discriminatory power (Abbes et al., 2012). The forward primers were labeled with carboxyfluorescein (FAM), hexachlorofluorescein (HEX), faststart universal SYBR Green Master (ROX), and carbosytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA). Amplification reactions were performed as previously reported (Abbes et al., 2012). Following PCR, amplicons were sized by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 3730XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems,) coupled with GeneMarker v1.8 software (SoftGenetics LLC, State College, PA, USA). Allele sizes were scored with respect to the GeneScan™ 500 LIZ® Size Standard (Applied Biosystems).

Antifungal susceptibility tests

Susceptibility tests were performed by using the Sensititre YeastOne™ YO10 (SYO) methodology (Thermo Scientific, Cleveland, OH, USA). Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and Candida krusei ATCC 6258 were quality control strains. MIC values were interpreted according to CLSI M27-S4 guidelines for fluconazole and echinocandins (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2012). The breakpoint for resistance to fluconazole is MIC > 32 μg/ml, to anidulafungin and caspofungin is MIC ≥ 0.5 μg/ml and to micafungin is MIC ≥ 0.25 μg/ml (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2012). Where there were no clinical break points (for voriconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, 5-flucytosine and amphotericin B), species-specific epidemiological cut-off values (ECVs) were used to define isolates as wide-type (WT) or non-WT. The ECV for non-WT to voriconazole and 5-flucytosine is MIC > 0.5 μg/ml and to itraconazole, posaconazole and amphotericin B is MIC > 2 μg/ml (Huang et al., 2014).

Statistical analysis

The genetic relationships of the isolates were determined by cluster analysis using the minimum-spanning tree available in the BioNumerics software v 6.5 (Applied Maths). To compare the discriminatory power of different molecular methods, we used an index of discrimination (D) based on Simpson's index of diversity and confidence intervals for D were determined by a method described previously by Grundmann et al. (2001).

Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS software (version 22.0; IBM SPSS Inc., New York, USA). Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. A P value of 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Source of isolates, demographics and body site of isolation

Of 411 isolates, 163 (39.7%) were from patients admitted in the Intensive care unit (ICU), 29.7% (122/411) from patients in the Surgery Department, 18.2% (75/411) from the Medical Department, 4.9% (20/411) from the Emergency Department and 7.5% (31/411) from other departments. The average age of the patients (241 males and 170 females) was 60 ± 18.4 years (range 0-96). Nearly one-half (200/411; 48.7%) of the isolates were obtained from blood cultures, 23.1% (95/411) were from ascitic fluid (Tables S1, S2), 5.1% (21/411) from pus and 4.6% (19/411) from venous catheter. The remaining isolates (N = 76) were obtained from bile, pleural fluid and other sterile body fluids.

MLST and microsatellite analysis

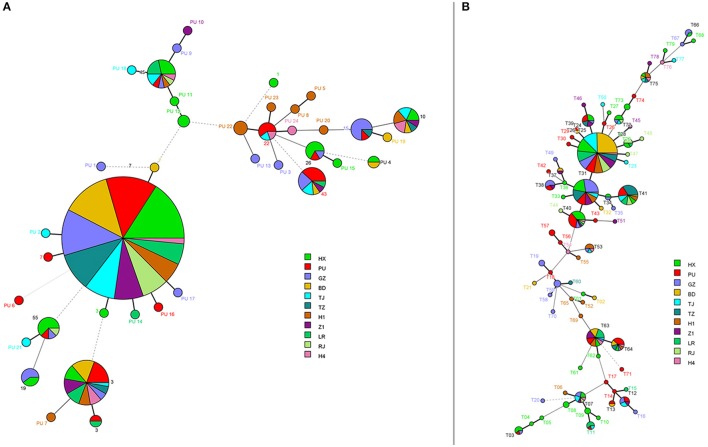

In general, MLST analysis revealed a low degree of genetic diversity within C. glabrata although the six-locus based MLST scheme showed a large number of STs overall—it allowed for the differentiation of 35 sequence types (STs) among 411 isolates, including 24 novel STs (PU 1-PU 24). The commonest ST, however, was ST7 (273/411 or 66.4% of isolates), where this ST was the predominant ST across all 11 hospitals, followed by ST3 (n = 39; 9.5%) (Figure 2A). The diversity index varied from 0.33 for UGP1 to 0.53 for NMT1/TRP1. The D value from all 6 markers was 0.55 (95% confidence interval: 0.49–0.61; Table 1).

Figure 2.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and microsatellites genotypes. The different circle colors represent different hospitals. In (A), each circle corresponds to a MLST ST. For (B), each circle corresponds to a microsatellite genotype.

Table 1.

Discriminatory power of the typing methods used in this study.

| Methods/Marker | No. of genotypes/Different allels | Index of discrimination |

|---|---|---|

| MLST | 35 | 0.55 |

| FKS | 9 | 0.5 |

| LEU2 | 9 | 0.47 |

| NMT1 | 14 | 0.53 |

| TRP1 | 16 | 0.53 |

| UGP1 | 7 | 0.33 |

| URA3 | 11 | 0.49 |

| Microsatellite | 79 | 0.88 |

| RPM2 | 4 | 0.46 |

| MTI | 8 | 0.61 |

| ERG3 | 14 | 0.52 |

| GLM4 | 13 | 0.71 |

| GLM5 | 14 | 0.7 |

| GLM6 | 10 | 0.53 |

MLST, multilocus sequence typing.

On analysis of ST according to body site of isolation, the majority of isolates from blood (136/200, 68%) and ascitic fluid (60/95, 63.2%), but also all from other specimen types were also of the ST7 type (n = 273, 66.4%) followed by ST3 (n = 39, 9.5%) (Table S1). Both these STs were identified in 10 of the 11 hospitals (Figure 2A) and further, were the predominant ST in all of fluconazole susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD; n = 343) and fluconazole-resistant isolates (n = 68) (Figures S1, S2). A further 10 STs, each encompassing two to 14 isolates, were also detected, whereas the remaining 23 STs comprised one isolate each (Table S1).

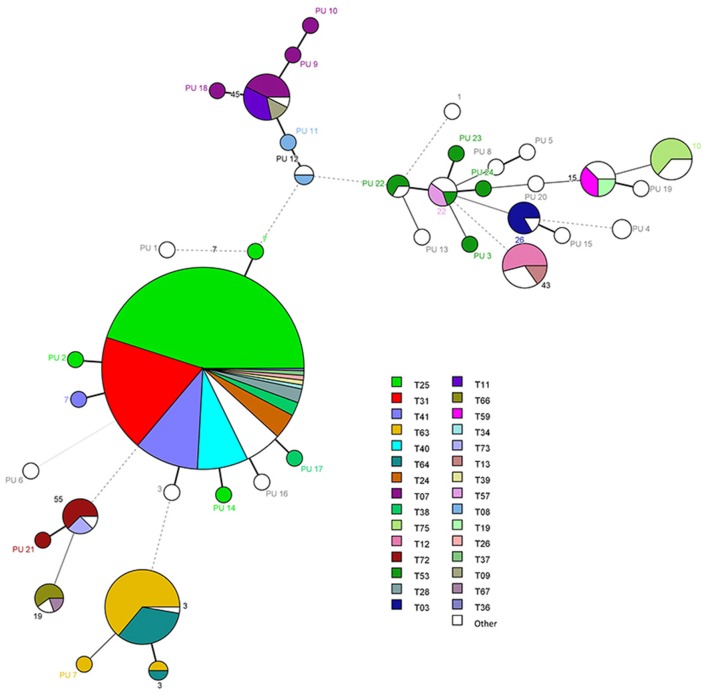

Using microsatellite analyses, there were 79 genotypes amongst the 411 isolates designated as genotypes T01 to T79 (Table 2, Figures 2B, 3). Of the 79 genotypes, T25 (n = 125, 30.4%) and T31 (n = 51, 12.4%) were the most prevalent followed by genotype T41 (n = 29, 7.1%). T25 and T31 were the predominant genotypes in fluconazole susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD) as well as fluconazole-resistant isolates. Overall genotype distribution was similar for all clinical samples (Figures S3, S4). Twenty-four genotypes each comprised 2–25 isolates, with the remaining 52 genotypes comprising one isolate each. The diversity index varied from 0.46 for RPM2 to 0.71 for GLM4. We found a D value of 0.88 (95% confidence interval: 0.86–0.90) by combining the six microsatellites (Table 1). Notably, there were 28 different microsatellite genotypes within ST7 (Figure 3), illustrating the higher D value of microsatellite-based polymorphism typing over MLST. The ST of C. glabrata was congruent (or consistent) with their microsatellite genotyping.

Table 2.

Designations of the 79 genotypes.

| Genotype | Designation of microsatellite markers | No. (%) of isolates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPM2 | ERG3 | MTI | GLM4 | GLM5 | GLM6 | ||

| T01 | 122 | 181 | 229 | 287 | 274 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T02 | 122 | 181 | 237 | 287 | 274 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T03 | 122 | 181 | 242 | 281 | 265 | 322 | 5 (1.2) |

| T04 | 122 | 181 | 242 | 284 | 265 | 322 | 1 (0.2) |

| T05 | 122 | 181 | 243 | 284 | 265 | 322 | 1 (0.2) |

| T06 | 122 | 234 | 243 | 266 | 262 | 247 | 1 (0.2) |

| T07 | 122 | 234 | 243 | 266 | 262 | 289 | 9 (2.2) |

| T08 | 122 | 234 | 243 | 266 | 265 | 289 | 2 (0.5) |

| T09 | 122 | 234 | 244 | 266 | 262 | 289 | 2 (0.5) |

| T10 | 122 | 234 | 244 | 266 | 265 | 289 | 1 (0.2) |

| T11 | 122 | 235 | 244 | 266 | 262 | 289 | 5 (1.2) |

| T12 | 122 | 238 | 242 | 293 | 262 | 310 | 7 (1.7) |

| T13 | 122 | 238 | 242 | 302 | 262 | 310 | 2 (0.5) |

| T14 | 122 | 238 | 242 | 305 | 262 | 310 | 1 (0.2) |

| T15 | 122 | 238 | 242 | 308 | 262 | 310 | 1 (0.2) |

| T16 | 122 | 238 | 243 | 293 | 262 | 310 | 1 (0.2) |

| T17 | 122 | 238 | 243 | 305 | 262 | 310 | 1 (0.2) |

| T18 | 128 | 181 | 229 | 278 | 268 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T19 | 128 | 181 | 229 | 284 | 268 | 325 | 2 (0.5) |

| T20 | 128 | 181 | 243 | 287 | 262 | 307 | 1 (0.2) |

| T21 | 128 | 181 | 250 | 278 | 268 | 322 | 1 (0.2) |

| T22 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 272 | 298 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T23 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 277 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T24 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 295 | 295 | 11 (2.7) |

| T25 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 298 | 295 | 125 (30.4) |

| T26 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 301 | 295 | 2 (0.5) |

| T27 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 301 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

| T28 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 304 | 295 | 6 (1.5) |

| T29 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 328 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T30 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 331 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T31 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 298 | 295 | 51 (12.4) |

| T32 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 298 | 301 | 1 (0.2) |

| T33 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 298 | 310 | 1 (0.2) |

| T34 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 301 | 295 | 2 (0.5) |

| T35 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 301 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

| T36 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 304 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T37 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 304 | 298 | 2 (0.5) |

| T38 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 304 | 301 | 7 (1.7) |

| T39 | 128 | 197 | 241 | 281 | 298 | 295 | 2 (0.5) |

| T40 | 128 | 197 | 242 | 278 | 298 | 295 | 22 (5.4) |

| T41 | 128 | 197 | 242 | 278 | 301 | 295 | 29 (7.1) |

| T42 | 128 | 197 | 242 | 278 | 304 | 307 | 1 (0.2) |

| T43 | 128 | 197 | 242 | 278 | 322 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T44 | 128 | 197 | 242 | 278 | 331 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T45 | 128 | 198 | 241 | 272 | 298 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T46 | 128 | 198 | 241 | 275 | 295 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T47 | 128 | 198 | 241 | 275 | 298 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T48 | 128 | 198 | 241 | 275 | 304 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T49 | 128 | 198 | 241 | 278 | 304 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

| T50 | 128 | 198 | 242 | 275 | 301 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T51 | 128 | 200 | 242 | 275 | 322 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T52 | 128 | 213 | 229 | 287 | 268 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T53 | 128 | 258 | 242 | 278 | 262 | 325 | 6 (1.5) |

| T54 | 128 | 262 | 242 | 278 | 259 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T55 | 128 | 262 | 242 | 278 | 259 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T56 | 128 | 262 | 243 | 278 | 265 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T57 | 128 | 262 | 243 | 281 | 259 | 325 | 2 (0.2) |

| T58 | 134 | 181 | 229 | 275 | 268 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T59 | 134 | 181 | 229 | 278 | 268 | 325 | 3 (0.2) |

| T60 | 134 | 181 | 229 | 281 | 268 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T61 | 134 | 204 | 237 | 269 | 280 | 301 | 1 (0.2) |

| T62 | 134 | 204 | 243 | 269 | 262 | 310 | 1 (0.2) |

| T63 | 134 | 204 | 243 | 269 | 262 | 325 | 25 (6.1) |

| T64 | 134 | 204 | 244 | 269 | 262 | 325 | 13 (3.2) |

| T65 | 134 | 213 | 229 | 287 | 268 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T66 | 134 | 213 | 241 | 281 | 265 | 298 | 3 (0.7) |

| T67 | 134 | 213 | 242 | 281 | 265 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

| T68 | 134 | 213 | 242 | 284 | 265 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

| T69 | 134 | 213 | 243 | 269 | 268 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T70 | 134 | 235 | 241 | 284 | 268 | 325 | 1 (0.2) |

| T71 | 134 | 238 | 261 | 269 | 265 | 292 | 1 (0.2) |

| T72 | 140 | 197 | 241 | 275 | 265 | 295 | 6 (1.5) |

| T73 | 140 | 197 | 241 | 278 | 265 | 295 | 2 (0.5) |

| T74 | 140 | 197 | 242 | 278 | 265 | 295 | 1 (0.2) |

| T75 | 140 | 228 | 242 | 278 | 265 | 298 | 7 (1.7) |

| T76 | 140 | 228 | 243 | 281 | 265 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

| T77 | 140 | 228 | 243 | 299 | 265 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

| T78 | 140 | 230 | 242 | 278 | 265 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

| T79 | 140 | 267 | 243 | 281 | 265 | 298 | 1 (0.2) |

The table shows the 79 genotypes (T01–T79) among 411 nonrepetitive Candida glabrata sensu stricto isolates generated by microsatellite genotyping.

Figure 3.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Each circle corresponds to a MLST ST. Different circle colors represent microsatellites genotypes.

Antifungal susceptibilities

The susceptibilities to antifungal drugs are shown in Table 3. Sixty-eight of 411 (16.5%) C. glabrata isolates were resistant to fluconazole (MICs >32 μg/mL) (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2012) with 40/200 (20%) of bloodstream isoaltes being resistant. The non-WT rates of C. glabrata for voriconazole, itraconazole and posaconazole were 28.7, 6.8, and 7.3% of isolates, respectively. Notably, 14.8% (61/411) of C. glabrata isolates were cross-resistant/non-WT to fluconazole and voriconazole. Caspofungin, micafungin and anidulafungin exhibited >99% susceptibility rates against all isolates. All isolates had WT MICs to amphotericin B. Only 0.2% (1/411) of C. glabrata isolates were non-WT to 5-flucytosine. The resistance rate for fluconazole increased significantly from 5.3% in 2013 to 31.4% in 2014 (P < 0.01) and non-WT rate for voriconazole increased significantly from 21.1% in 2013 to 82.6% in 2014 (P < 0.05). While the non-WT rate for itraconazole and posaconazole both decreased from 8.4% in 2012 to 1.3% in 2013 (P < 0.05) and remains 3.5% in 2014. There were no significant trends for resistance rate or non-WT rate for echinocandins, amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine (all the P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Antifungal susceptibilities for Candida glabrata species collected in this study.

| Parameter | Fluconazole | Voriconazole | Itraconazole | Posaconazole | Anidulafungin | Micafungin | Caspofungin | 5-flucytosine | Amphotericin B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 1–>256 | 0.03–>8 | 0.12–>16 | 0.25–>8 | ≤0.015–>8 | ≤0.008–>8 | ≤0.008–>8 | ≤0.06–>64 | ≤0.12–2 |

| MIC90 | 64 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.015 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 1 |

| MIC50 | 16 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.03 | 0.015 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.5 |

| 0.78 | 19.29 | 0.36 | 1.20 | 0.028 | 0.013 | 0.073 | 0.062 | 0.65 | |

| R/non-WT (%) | 16.5 | 28.7 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0 |

GM, geometric mean; R, resistant; non-WT, non-wide-type.

Discussion

Candida glabrata is an increasingly important pathogen in the United States and Europe but also in China (Pfaller et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2012; Guinea, 2014; Xiao et al., 2015; Delliere et al., 2016). Knowledge of both the diversity of molecular types, as well as antifungal susceptibility profiles of C. glabrata are important for understanding the epidemiology of this organism. Our study, for the first time, provides a description of the genetic diversity and antifungal susceptibility of a large number of C. glabrata strains. Major findings of the study included the observations that fluconazole resistant rates increased 3-fold over the 5-year period, the frequency of isolates with non-WT MICs to voriconazole rose 7-fold, and that Chinese C. glabrata sensu stricto isolates exhibit relatively low intraspecies genetic diversity.

Despite the position of C. glabrata as a pathogen in China, we noted that the isolation rate of C. glabrata slightly decreased in 2013 from 2010. The reason for this apparent drop may be because of a large-scale outbreak of Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto fungemia involving >100 isolates in one of the 11 participating hospitals during the study period (Wang et al., 2016). Nonetheless C. glabrata accounted for 10.2% (200/1963) of candidemia cases in the present study, similar to that found in Finland (9.0%) and Norway (13.2%) (Guinea, 2014) but substantially less than that in Denmark (25%) and the USA (21%) (Pfaller et al., 2001; Arendrup et al., 2011). In this study, most of isolates were recovered from blood (200/411; 48.7%), while in a French study, most of isolates were collected from respiratory sample (81/268; 30.2%) (Delliere et al., 2016).

Strain typing is essential for epidemiological investigation and a variety of molecular methods have been applied for genotyping of C. glabrata. PFGE exhibits high discriminatory power, but is limited by the high initial investment costs and slow turn-around times (Abbes et al., 2010). MLST has the advantage of providing unambiguous results, which allows different laboratories to easily compare data and allows for the construction of international internet-accessible databases (Dodgson et al., 2003). However, the D value was only 0.55 in the present study. It has been reported that MLST system developed for C. glabrata appears to be less discriminatory than that for C. albicans. One plausible explanation is that C. albicans is a diploid organism, as opposed to the haploid status of C. glabrata, which allows for greater potential for detecting the presence of genetic heterogeneity with the former (Dodgson et al., 2003). As such, we found a low degree of genetic diversity amongst C. glabrata using MLST analysis. The majority (75.9%) of isolates comprised only two STs, ST7 and ST3. C. glabrata ST3 and ST5 types have been predominant in Europe, while ST7 and ST30 types are reported to be the most common in Japan (Dodgson et al., 2003), and ST8 and ST18 types in the USA (Dodgson et al., 2003). The differences in STs according to geography, highlight the significance of acquiring local data.

The results of the present study show that in comparison to MLST, the D-value for microsatellite typing was 0.88, higher than MLST employed herein, but lower than that in one study using microsatellite analysis (Abbes et al., 2012). Nonetheless, the results of microsatellite genotyping in our study were concordant with those of a predominant genotype identified. Our isolates were collected only from Chinese patients and it is logical that coevolution of genetic markers will provide similar results by any chose typing method. The D-value may be improved by incorporation of a greater number of more loci by the microsatellite analysis approach and this is the focus of ongoing study (Dodgson et al., 2003; Foulet et al., 2005; Abbes et al., 2012; Delliere et al., 2016). This approach is also simple to use and is inexpensive (US$9 per sample analyzed vs. US$24 for MLST).

Of note, there was no correlation between genetic type and isolates from patients at the different hospitals or from departments by either MLST or microsatellite typing. We also found no association between genetic type and susceptibility to fluconazole (Tables S1, S2, Figures S1, S3). However, our results do not exclude the possibility that certain STs or microsatellite genotypes may have the capacity to acquire resistance through drug exposure at differing frequencies. Many studies have likewise found no association between C. glabrata genotypes and antifungal resistance (Dodgson et al., 2003; Abbes et al., 2011). However, Dhieb et al. noted that both microsatellite genotypes and MALDI-TOF MS analysis could highlight C. glabrata population structures associated with specific geographic origin or antifungal drug resistance pattern (Dhieb et al., 2015). In our study, we noticed that during 2010–2011 in one hospital (Hospital BD) 80.8% (21/26) C. glabrata isolates were of the same genetic type (ST7 and T25), suggesting possible clonal presence/transmission of C. glabrata. 14 isolates were from blood, four from ascitic fluid, two from venous catheter and one from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and five of these isolates (5/21, 23.8%) were collected from patients in the same department and were resistant to fluconazole. Further study is needed to investigate the clinical events at this hospital stemming from this observation.

Importantly, our results show that only 6.8% of C. glabrata isolates were non-WT/resistant to all four azoles tested in contrast to results noted in the USA (Pfaller et al., 2004), but comparable to those reported by Wang et al. (2012) and Delliere et al. (2016). Of note, however, the proportion of isolates that were fluconazole–resistant and/or had non-WT MICs to voriconazole rose significantly over 5 years. That many of these isolates remained susceptible to posaconazole and itraconazole underscores the importance of susceptibility testing for individual isolates.

Echinocandins have become the first-line treatment of IC caused by C. glabrata (Pfaller et al., 2012). In this context, the fact that only two isolates (0.5% of all isolates) tested resistant to the echinocandins (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2012) is reassuring. One C. glabrata isolate was observed to have an MIC > 8 μg/mL to all three echinocandins. The low rate of echinocandin resistance here contrasts with that in the USA and elsewhere where resistance has bene reported in up to 10% and with one-third of those isolates being multidrug resistant (Pfaller et al., 2012; Alexander et al., 2013; Eschenauer et al., 2014; Pham et al., 2014). However, one French study observed only a low proportion of isolates to be resistant to micafungin (0.7%) using the Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) and employing European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) breakpoints, with only 1/268 isolates showing cross-resistance to both antifungal classes (Delliere et al., 2016). Importantly, one echinocandin-resistant isolate in the present study was also resistant to fluconazole, which MICs for fluconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole and posaconazole were 128, 8, ≥16, and ≥8 μg/mL, respectively and 0.5 μg/mL for echinocandins. This is the first multi-drug resistant isolate reported in China. Elsewhere, about 11.1% of fluconazole-resistant C. glabrata were co-resistant to one or more echinocandins study (Pfaller et al., 2012).

One study limitation is that we used the SYO methodology to perform antifungal susceptibility testing. The essential agreement between this methodology and the CLSI as well as with the EUCAST reference procedures are known to be very high (Cuenca-Estrella and Rodriguez-Tudela, 2010; Posteraro and Sanguinetti, 2014). In addition, the Sensititre method is a simple and affordable alternative to these reference methodologies and is widely used in clinical mycology laboratories (Posteraro and Sanguinetti, 2014).

Conclusion

This is the first systemic study regarding the molecular epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility profiles of C. glabrata isolates in China. Identification of relatedness between C. glabrata is important in understanding their molecular epidemiology. Our results suggest that some C. glabrata populations are more prominent than others. Further investigations are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Author contributions

XH, MX, YZ, and YX conceived and designed the research; XH, GZ, HW, and XF collaborated in molecular investigations of the strains; HW, SC, FK, YC, MK, ZS, ZH, RL, JL, KL, TH, YN, and G-LZ provided yeasts and analyzed the data; XH, MX, SC, and FK wrote the manuscript. All authors read, improved and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Special Fund for Public Welfare Industry of Health (No. 201402001), the Innovation Fund of Peking Union Medical College (No. 2016-1001-15) and CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (No. 2016-I2M-1-014). Funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decisions to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the laboratories that participated in the CHIF-NET program in 2010-2014. The 11 hospitals enrolled in this study were (hospital name and abbreviation, and city location): Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PU), Beijing; The First Hospital of China Medical University (Z1), Shenyang; West China Hospital (HX), Chengdu; Tongji Hospital (TJ), Wuhan; Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (TZ), Tianjin; Peking University First Hospital (BD), Beijing; The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (H1), Harbin; The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (GZ), Guangzhou; The People's Hospital of Liaoning Province (LR), Shenyang; Ruijin Hospital Affiliated to School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiaotong University (RJ), Shanghai; The Fourth Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University (H4), Harbin.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00880/full#supplementary-material

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Different circle colors represent fluconazole susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD) (green) or resistant (MIC > 32 μg/ML) (red). Each circle in corresponds to a MLST ST.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Different circle colors represent sample types. Each circle in corresponds to a MLST ST.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of microsatellites genotypes. Different circle colors represent fluconazole susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD) (green) or resistant (MIC > 32 μg/ML) (red). Each circle in corresponds to a microsatellites genotype.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of microsatellites genotypes. Different circle colors represent sample types. Each circle in corresponds to a microsatellites genotype.

Distribution of Candida glabrata isolates of different sequence types (STs) in different specimen types and prevalence of fluconazole resistant (MIC > 32 μg/mL) isolates.

Distribution of Candida glabrata isolates of different microsatellite genotypes in different specimen types and prevalence of fluconazole resistant (MIC > 32 μg/mL) isolates.

References

- Abbes S., Amouri I., Sellami H., Sellami A., Makni F., Ayadi A. (2010). A review of molecular techniques to type Candida glabrata isolates. Mycoses 53, 463–467. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01753.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbes S., Sellami H., Sellami A., Hadrich I., Amouri I., Mahfoudh N., et al. (2012). Candida glabrata strain relatedness by new microsatellite markers. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31, 83–91. 10.1007/s10096-011-1280-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbes S., Sellami H., Sellami A., Makni F., Mahfoudh N., Makni H., et al. (2011). Microsatellite analysis and susceptibility to FCZ of Candida glabrata invasive isolates in Sfax Hospital, Tunisia. Med. Mycol. 49, 10–15. 10.3109/13693786.2010.493561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander B. D., Johnson M. D., Pfeiffer C. D., Jimenez-Ortigosa C., Catania J., Booker R., et al. (2013). Increasing echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata: clinical failure correlates with presence of FKS mutations and elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 56, 1724–1732. 10.1093/cid/cit136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendrup M. C., Bruun B., Christensen J. J., Fuursted K., Johansen H. K., Kjaeldgaard P., et al. (2011). National surveillance of fungemia in Denmark (2004 to 2009). J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 325–334. 10.1128/JCM.01811-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisse S., Pannier C., Angoulvant A., de Meeus T., Diancourt L., Faure O., et al. (2009). Uneven distribution of mating types among genotypes of Candida glabrata isolates from clinical samples. Eukaryotic Cell 8, 287–295. 10.1128/EC.00215-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca-Estrella M., Rodriguez-Tudela J. L. (2010). The current role of the reference procedures by CLSI and EUCAST in the detection of resistance to antifungal agents in vitro. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 8, 267–276. 10.1586/eri.10.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delliere S., Healey K., Gits-Muselli M., Carrara B., Barbaro A., Guigue N., et al. (2016). Fluconazole and echinocandin resistance of Candida glabrata correlates better with antifungal drug exposure rather than with MSH2 mutator genotype in a French cohort of patients harboring low rates of resistance. Front. Microbiol. 7:2038. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhieb C., Normand A. C., Al-Yasiri M., Chaker E., El Euch D., Vranckx K., et al. (2015). MALDI-TOF typing highlights geographical and fluconazole resistance clusters in Candida glabrata. Med. Mycol. 53, 462–469. 10.1093/mmy/myv013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodgson A. R., Pujol C., Denning D. W., Soll D. R., Fox A. J. (2003). Multilocus sequence typing of Candida glabrata reveals geographically enriched clades. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 5709–5717. 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5709-5717.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enache-Angoulvant A., Bourget M., Brisse S., Stockman-Pannier C., Diancourt L., Francois N., et al. (2010). Multilocus microsatellite markers for molecular typing of Candida glabrata: application to analysis of genetic relationships between bloodstream and digestive system isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 4028–4034. 10.1128/JCM.02140-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenauer G. A., Nguyen M. H., Shoham S., Vazquez J. A., Morris A. J., Pasculle W. A., et al. (2014). Real-world experience with echinocandin MICs against Candida species in a multicenter study of hospitals that routinely perform susceptibility testing of bloodstream isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 1897–1906. 10.1128/AAC.02163-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulet F., Nicolas N., Eloy O., Botterel F., Gantier J. C., Costa J. M., et al. (2005). Microsatellite marker analysis as a typing system for Candida glabrata. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 4574–4579. 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4574-4579.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann H., Hori S., Tanner G. (2001). Determining confidence intervals when measuring genetic diversity and the discriminatory abilities of typing methods for microorganisms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 4190–4192. 10.1128/JCM.39.11.4190-4192.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinea J. (2014). Global trends in the distribution of Candida species causing candidemia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20(Suppl. 6), 5–10. 10.1111/1469-0691.12539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjeh R. A., Sofair A. N., Harrison L. H., Lyon G. M., Arthington-Skaggs B. A., Mirza S. A., et al. (2004). Incidence of bloodstream infections due to Candida species and in vitro susceptibilities of isolates collected from 1998 to 2000 in a population-based active surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 1519–1527. 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1519-1527.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X., Xiao M., Chen S. C., Wang H., Yu S. Y., Fan X., et al. (2017). Identification and antifungal susceptibility profiles of Candida nivariensis and Candida bracarensis in a multi-center Chinese collection of yeasts. Front. Microbiol. 8:5. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y. T., Liu C. Y., Liao C. H., Chung K. P., Sheng W. H., Hsueh P. R. (2014). Antifungal susceptibilities of Candida isolates causing bloodstream infections at a medical center in Taiwan, 2009-2010. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3814–3819. 10.1128/AAC.01035-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullberg B. J., Arendrup M. C. (2015). Invasive candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1445–1456. 10.1056/NEJMra1315399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. Y., Chen Y. C., Lo H. J., Chen K. W., Li S. Y. (2007). Assessment of Candida glabrata strain relatedness by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 2452–2459. 10.1128/JCM.00699-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas P. G., Kauffman C. A., Andes D. R., Clancy C. J., Marr K. A., Ostrosky-Zeichner L., et al. (2016). Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62, 409–417. 10.1093/cid/civ1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Castanheira M., Lockhart S. R., Ahlquist A. M., Messer S. A., Jones R. N. (2012). Frequency of decreased susceptibility and resistance to echinocandins among fluconazole-resistant bloodstream isolates of Candida glabrata. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1199–1203. 10.1128/JCM.06112-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Diekema D. J., Jones R. N., Sader H. S., Fluit A. C., Hollis R. J., et al. (2001). International surveillance of bloodstream infections due to Candida species: frequency of occurrence and in vitro susceptibilities to fluconazole, ravuconazole, and voriconazole of isolates collected from 1997 through 1999 in the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 3254–3259. 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3254-3259.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller M. A., Messer S. A., Boyken L., Tendolkar S., Hollis R. J., Diekema D. J. (2004). Geographic variation in the susceptibilities of invasive isolates of Candida glabrata to seven systemically active antifungal agents: a global assessment from the ARTEMIS antifungal surveillance program conducted in 2001 and 2002. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 3142–3146. 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3142-3146.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham C. D., Iqbal N., Bolden C. B., Kuykendall R. J., Harrison L. H., Farley M. M., et al. (2014). Role of FKS mutations in Candida glabrata: MIC values, echinocandin resistance, and multidrug resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 4690–4696. 10.1128/AAC.03255-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posteraro B., Sanguinetti M. (2014). The future of fungal susceptibility testing. Future Microbiol. 9, 947–967. 10.2217/fmb.14.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2012). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts: Fourth Informational Supplement M27-S4. Wayne, PA: CLSI. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Xiao M., Chen S. C., Kong F., Sun Z. Y., Liao K., et al. (2012). In vitro susceptibilities of yeast species to fluconazole and voriconazole as determined by the 2010 National China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net (CHIF-NET) study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 3952–3959. 10.1128/JCM.01130-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhang L., Kudinha T., Kong F., Ma X. J., Chu Y. Z., et al. (2016). Investigation of an unrecognized large-scale outbreak of Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto fungaemia in a tertiary-care hospital in China. Sci. Rep. 6:27099. 10.1038/srep27099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisplinghoff H., Bischoff T., Tallent S. M., Seifert H., Wenzel R. P., Edmond M. B. (2004). Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39, 309–317. 10.1086/421946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao M., Fan X., Chen S. C., Wang H., Sun Z. Y., Liao K., et al. (2015). Antifungal susceptibilities of Candida glabrata species complex, Candida krusei, Candida parapsilosis species complex and Candida tropicalis causing invasive candidiasis in China: 3 year national surveillance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 802–810. 10.1093/jac/dku460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yapar N. (2014). Epidemiology and risk factors for invasive candidiasis. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 10, 95–105. 10.2147/TCRM.S40160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Xiao M., Wang H., Gao R., Fan X., Brown M., et al. (2014). Yeast identification algorithm based on use of the Vitek MS system selectively supplemented with ribosomal DNA sequencing: proposal of a reference assay for invasive fungal surveillance programs in China. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 572–577. 10.1128/JCM.02543-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Different circle colors represent fluconazole susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD) (green) or resistant (MIC > 32 μg/ML) (red). Each circle in corresponds to a MLST ST.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Different circle colors represent sample types. Each circle in corresponds to a MLST ST.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of microsatellites genotypes. Different circle colors represent fluconazole susceptible-dose dependent (S-DD) (green) or resistant (MIC > 32 μg/ML) (red). Each circle in corresponds to a microsatellites genotype.

Minimum spanning tree analysis based on allelic profiles of microsatellites genotypes. Different circle colors represent sample types. Each circle in corresponds to a microsatellites genotype.

Distribution of Candida glabrata isolates of different sequence types (STs) in different specimen types and prevalence of fluconazole resistant (MIC > 32 μg/mL) isolates.

Distribution of Candida glabrata isolates of different microsatellite genotypes in different specimen types and prevalence of fluconazole resistant (MIC > 32 μg/mL) isolates.