Abstract

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-IMS) is an advanced method used globally to analyze the distribution of biomolecules on tissue cryosections without any probes. In bones, however, hydroxyapatite crystals make it difficult to determine the distribution of biomolecules using MALDI-IMS. Additionally, there is limited information regarding the use of this method to analyze bone tissues. To determine whether MALDI-IMS analysis of bone tissues can facilitate comprehensive mapping of biomolecules in mouse bone, we first dissected femurs and tibiae from 8-week-old male mice and characterized the quality of multiple fixation and decalcification methods for preparation of the samples. Cryosections were mounted on indium tin oxide-coated glass slides, dried, and then a matrix solution was sprayed on the tissue surface. Images were acquired using an iMScope at a mass-to-charge range of 100–1000. Hematoxylin-eosin, Alcian blue, Azan, and periodic acid-Schiff staining of adjacent sections was used to evaluate histological and histochemical features. Among the various fixation and decalcification conditions, sections from trichloroacetic acid-treated samples were most suitable to examine both histology and comprehensive MS images. However, histotypic MS signals were detected in all sections. In addition to the MS images, phosphocholine was identified as a candidate metabolite. These results indicate successful detection of biomolecules in bone using MALDI-IMS. Although analytical procedures and compositional adjustment regarding the performance of the device still require further development, IMS appears to be a powerful tool to determine the distribution of biomolecules in bone tissues.

Keywords: Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-imaging mass spectrometry, Tissue cryosection, Bone, Fixation, Decalcification

Highlights

-

•

There is limited information regarding the use of MALDI-IMS to analyze bones.

-

•

TCA treatment was most suitable to examine both histology and comprehensive MS images.

-

•

Phosphocholine was identified as a candidate metabolite in bone using MALDI-IMS.

1. Introduction

Recent advances in omics approaches allow for the identification of whole molecules constituting an organism, which can provide insight into pathogenic processes and serve as biomarker candidates. Information obtained from omics research, such as proteomics and metabolomics, has become particularly important for elucidating etiology and for diagnosis of diseases. However, conventional imaging techniques, such as immunohistochemistry, require labeling and have limited use for revealing new pathological molecules in tissue.

Mass spectrometry (MS) is a commonly used technology to detect analytes in proteomics and metabolomics research, and can directly define individual molecular species in complex samples. Among MS methods, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-IMS) enables analysis of the molecule distribution without any disruption of the morphology or architecture. In contrast, liquid chromatography-MS or gas chromatography-MS analyses require the use of tissue homogenates, which retains no tissue localization information.

Although cellular and molecular analyses are useful for many types of tissues, they are difficult to use with calcified tissues such as bones and teeth. This limits investigation of the function of cells such as osteocytes and cementocytes, or the distribution of organic matter such as proteins and peptides. For example, osteocytes, which terminally differentiate from osteoblasts and are embedded in the bone matrix, play an important role in the maintenance of homeostasis in the network between osteoblasts and osteoclasts (Bonewald, 2011). To examine the physiological functions of osteocytes, it is preferable to retain the original distribution of biomolecules. However, MALDI-IMS has certain limitations for quantitative and qualitative uncertainty analyses. Additionally, there are few studies that have applied MALDI-IMS to bone tissues to identify molecules because of the lack of appropriate methods to prepare sections for ionization (Hirano et al., 2014, Cillero-Pastor et al., 2015, Seeley et al., 2014). Hirano et al. (Hirano et al., 2014) reported MALDI-IMS for tooth cryosections prepared by the Kawamoto method using adhesive film without any pretreatment, such as fixation or decalcification. However, the signals obtained from the enamel and dentin were not listed in the metabolomics database. They concluded that almost all of these signals were mineral which can interrupt ionization of large components.

Therefore, in this study we established a protocol to fix and decalcify samples derived from bone to detect MS using MALDI-IMS and provide a comprehensive map of proteins and peptides.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Conductive indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass slides (8–12 Ω) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO). α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) matrices were purchased from Bruker Daltonics (Bremen, Germany). Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC; 2%) was purchased from Leica Microsystems (Wetzlar, Germany). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 2,5-dihydroxy-benzoic acid (DHB), and all other chemicals, unless specified otherwise, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co.

2.2. Animals

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from CLEA Inc. (Osaka, Japan). The mice were housed and handled to minimize pain and discomfort according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Central Institute for Experimental Animals and the Committee of Animal Experimentation at Hiroshima University.

2.3. Specimen preparation

Femurs and/or tibiae from 8-week-old male mice were fixed and decalcified in various combinations of fixatives [4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), Carnoy fluid or trichloroacetic acid (TCA)] and decalcification solutions (formic acid, EDTA-NH4, or TCA) (Table 1). Fresh samples, with or without decalcification, were also prepared. The samples were then embedded in a stainless steel container filled with 2% CMC and placed in dry ice-cooled hexane to prepare frozen CMC blocks. Each frozen block was stored at − 80 °C until sectioning. Tissues were sectioned (5 μm for staining and MALDI-IMS of fresh samples without any pretreatment by the Kawamoto method (Kawamoto, 2003), and 10 μm for MALDI-IMS of samples with pretreatment) with a CM 3050 S cryostat (Leica Microsystems). For staining, the sections were placed on normal glass slides and washed with 100% ethanol. For MALDI-IMS, the sections were placed on ITO-coated glass slides with electrically conducting double-adhesive tape for samples without pretreatment, followed by washing with 70% and then 100% ethanol, and dried.

Table 1.

Combinations of fixation and decalcification solutions.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation | – | TCA, overnight | PFA, overnight | Carnoy, overnight | PFA, overnight | Carnoy, overnight | – | – |

| Decalcification | – | EDTA, 7 days | EDTA, 7 days | Formic acid, 2 days | Formic acid, 2 days | Formic acid, 2 days | EDTA, 4 days |

2.4. Staining

Adjacent sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H-E), Alcian blue, Azan, and Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) to evaluate histological and histochemical features. Sections that did not undergo previous fixation were fixed with 4% PFA before staining.

2.5. MALDI-IMS and MS-MS

After drying at room temperature, cryosections were coated with a DHB or CHCA matrix vapor deposition using an iMlayer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) at a thickness of 1.5 or 0.7 μm, respectively. MALDI images were acquired using an iMScope (Shimadzu Corporation) in positive or negative ion modes in the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) range of 100–1000, at a laser frequency of 1000 Hz, accumulating 50 laser shots. Detector and sample voltages were 1.7–1.9 kV and 3–3.5 kV, respectively. Spatial resolution was 10 μm and laser intensity ranged from 23 to 45. To prevent any influence of fixation and decalcification solutions as well as matrices, 1 μL of each solution and matrix was placed onto a stainless steel plate and applied to the iMScope after drying. Mass spectra obtained from this mixture were omitted from spectra of the samples. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to extract the peak matrix from the mass spectrum and search for principal components as characteristic patterns in the images (Shao et al., 2012).

To identify the metabolites in bones, the TCA-treated sections from mouse femurs were applied to iMScope in positive ion mode with the DHB matrix. MS-MS data were evaluated using the Human Metabolome Database search engine (version 3.6, The Metabolomics Innovaton Centre, Edmonton, Canada) for metabolite identification.

Phosphocholine inferred by MS-MS data was mixed with DHB and applied to the iMScope. The MS-MS spectrum was compared with that detected in sections.

3. Results

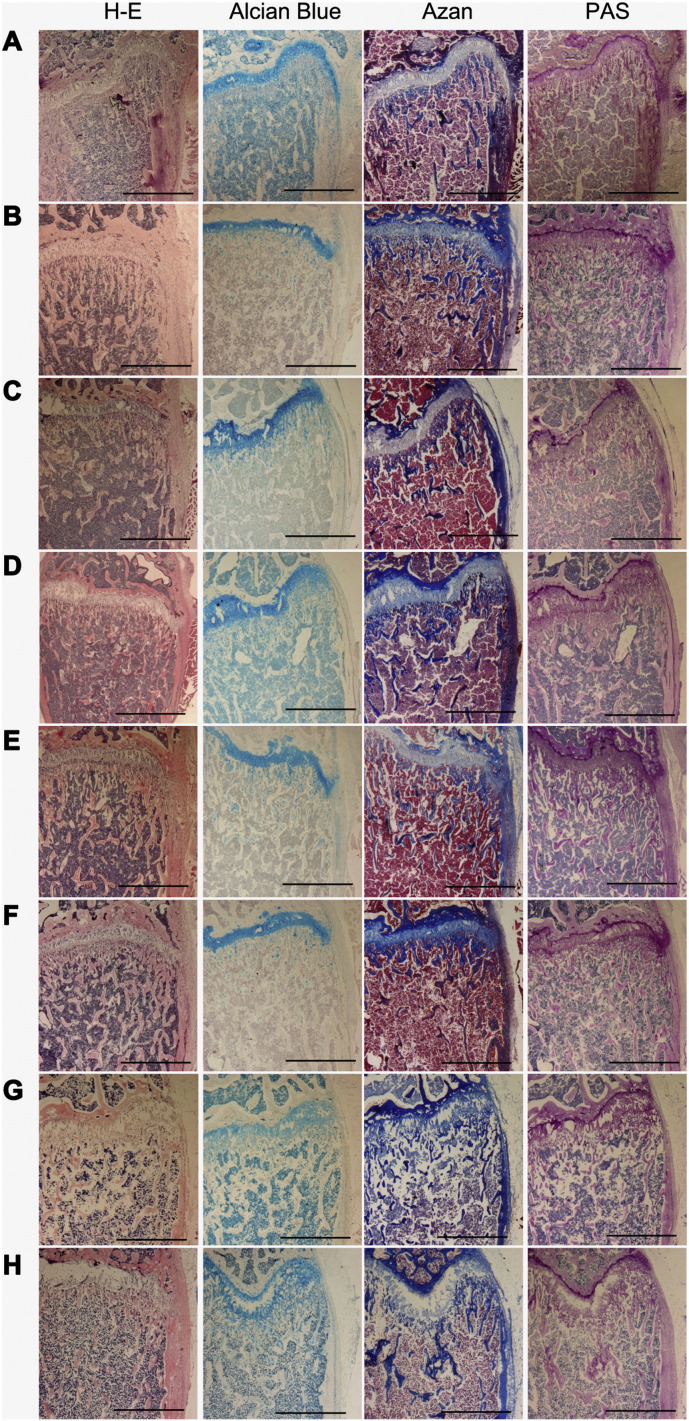

3.1. Histological and histochemical features of bones with or without pretreatment

To evaluate the influence of fixation and decalcification solutions on the histological and histochemical features of femurs and tibiae, cryosections were stained with H-E, Alcian blue, Azan, and PAS. Among the various fixation and decalcification conditions, sections from TCA-treated samples were the most suitable to examine both histology and comprehensive MS images (Fig. 1B), followed by samples decalcified with EDTA after fixation (Fig. 1C, D). Bone marrow peeled from trabecular bone surfaces in samples decalcified with formic acid (Fig. 1E, F). Cartilage in the growth plate and bone marrow were unable to keep their structure in decalcified samples without fixation (Fig. 1G, H). There was no difference between samples with Azan or PAS staining. However, with Alcian Blue staining, bone marrow in unfixed and Carnoy/EDTA-treated samples turned dark blue (Fig. 1A, D, G, and H).

Fig. 1.

Histological observations of femurs and tibiae fixed and decalcified with each solution by hematoxylin-eosin (H-E), Alcian blue, Azan, and Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining.

(A) Sections of unfixed/undecalcified tibiae. (B) Sections of trichloroacetic acid (TCA)-treated femurs. (C–H) Sections of femurs treated with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/EDTA (C), Carnoy/EDTA (D), PFA/formic acid (E), or Carnoy/formic acid (F). (G, H), Unfixed sections of femurs decalcified with formic acid (G) or EDTA (H). Representative images are shown; n = 2–5.

3.2. Comparison of MALDI-IMS between bones with or without pretreatment

In MALDI-IMS analysis, an appropriate matrix is required to obtain successful images (Setou and Kurabe, 2011). To establish the measurement conditions of MALDI-IMS, all samples were applied to the iMScope in positive or negative ion modes with DHB or CHCA matrices. Among these conditions, the positive mode with DHB enabled detection of many mass spectra in a wide range of m/z (Fig. 2A, samples treated with TCA). Imaging by MALDI-IMS showed tissue-specific distribution of MS with DHB (Fig. 2B). Because the Kawamoto method requires cryofilm, MALDI-IMS of TCA-treated sections mounted on ITO-coated glass slides with or without cryofilm were analyzed to measure the interference of cryofilm. With cryofilm, the number of mass spectra was much less than without cryofilm (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Mass spectra (maximum intensity) and MALDI-IMS analysis of TCA-treated samples in the range of m/z 100–1000 under various conditions.

(A) Analysis with a 2,5-dihydroxy-benzoic acid (DHB) or α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) matrix in positive or negative ion modes in the range of m/z 100–1000. (B) Imaging of the histotypic distribution of several mass peaks from the sections. Left panels show optical images and H-E staining. (C) Mass spectra detected in sections with or without cryofilm in the range of m/z 100–1000. Representative images and data are shown. n > 3.

A comparison of mass spectra detected in positive ion mode with DHB showed that the undecalcified sample with the Kawamoto method exhibited few peaks in the range of m/z 100–700 (Fig. 3). Each section had its own characteristic features of the appearance of peaks, but there was no significant difference in the obtained number of mass spectra between samples that were decalcified, fixed, or both (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Mass spectra (maximum intensity) of each treatment with MALDI-IMS in the range of 100–1000 and the positive ion mode with DHB.

Sections of unfixed/undecalcified tibiae, femurs treated with TCA, PFA/EDTA, Carnoy/EDTA, PFA/formic acid, or Carnoy/formic acid, and femurs decalcified with formic acid or EDTA in the range of m/z 100–1000. Representative data are shown. n > 3.

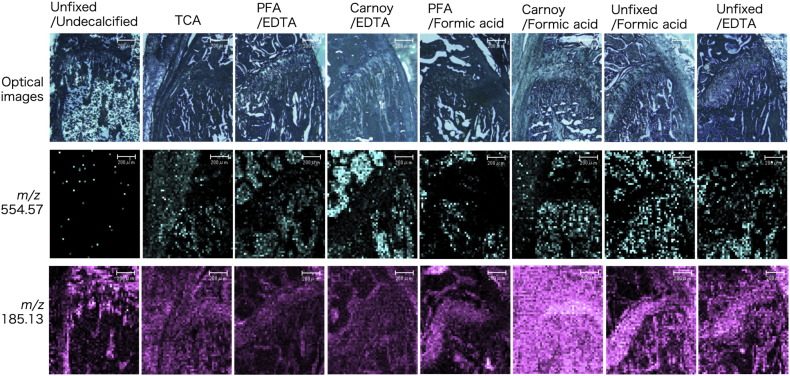

In MALDI-IMS, histotypic MS signals were detected in all sections. The signals of the molecule at m/z 554.57 were located mainly in bone marrow in all sections except undecalcified sections. The molecule at m/z 185.13 was located mainly in cortical bones, trabecular bones, and cartilage in all sections except the Carnoy/formic acid sample (Fig. 4). In the undecalcified section, there were a few signals at m/z 554.57, and the signals at m/z 185.13 were localized diffusely in the Carnoy/formic acid sample (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

MALDI-IMS at m/z 554.57 and m/z 185.13 of each treatment.

Optical images (upper). MALDI-IMS at m/z 554.57 (middle) and at m/z 185.13 (lower) with indicated treatment. Representative images and data are shown. n > 3.

PCA, a statistical method to extract the first principal component in variance between samples, revealed that the first principal component was the same in samples except undecalcified, Carnoy/EDTA, and PFA/formic acid samples in the range of m/z 100–700 (Table 2).

Table 2.

First principal component with or without pretreatment.

| Unfixed/undecalcified | TCA | PFA/EDTA | Carnoy/EDTA | PFA/formic acid | Carnoy/formic acid | Unfixed/formic acid | Unfixed/EDTA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z 100–400 | 165.07 | 114.91 | 114.91 | 114.91 | 184.08 | 114.91 | 114.91 | 114.91 |

| m/z 400–700 | 456.11 | 462.73 | 462.73 | 412.71 | 462.73 | 462.73 | 462.73 | 462.73 |

3.3. Metabolomics of mouse femurs

To identify metabolites in bone, TCA-treated sections from mouse femurs were applied to the iMScope in positive ion mode with the DHB matrix. Several MS-MS data sets were subjected to the human metabolome database, and some high-scoring candidates were recovered. Of these, the molecule at m/z 184.07 was identified as phosphocholine (Fig. 5B). For confirmation, an authentic sample of phosphocholine was applied to the iMScope. The MS-MS spectra were in agreement with those obtained from the tissue sections (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

MS-MS data at m/z 184.07 in sections and an authentic sample of phosphocholine.

(A) An optical image (left), H-E staining (middle), and MS image at m/z 184.07 (right). (B) MS-MS spectra of an authentic sample of phosphocholine. (C) Product ions predicted a part of the structure as indicated by the arrow. n = 3.

4. Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively determined the metabolomics of mouse bones with localization information using MALDI-IMS. We also characterized different fixation and decalcification techniques and established an effective method for preparation of mouse bone tissue.

When preparing cryosections of hard tissues without decalcification, the Kawamoto method requires cryofilm that can attach to the cutting surface under freezing conditions (Kawamoto, 2003). Furthermore, for ionization, an electrically conducting double-adhesive tape is needed to affix sections on the ITO-glass slide (Hirano et al., 2014). Comparison of mass spectra between sections with or without tape revealed that many more peaks were obtained from the section without tape. A method has been reported to remove the tape before application to MALDI-IMS (Seeley et al., 2014), but a high degree of technical skill is required to do so.

For MALDI-IMS, fresh frozen sections (without fixation) are usually used for analysis. This study showed that fixation and decalcification of bones facilitates the preparation of sections, and detection of MS from organic components is possible because of mineral removal. Because the utility of MALDI-IMS has been reported for formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues (Lemaire et al., 2007), researchers have focused on analysis of FFPE samples by MALDI-IMS (Ronci et al., 2008, Djidja et al., 2009, Stauber et al., 2010, Cole et al., 2013, Powers et al., 2014, Gravius et al., 2015, O'Rourke et al., 2015). Formalin fixation can be used to avoid degradation and spoilage of samples. However, the cross-linked molecules between formalin and primary amines are unable to be ionized. Therefore, the number of identified proteins in FFPE sections is less than that in cryosections, and several steps are required to remove formalin, break crosslinks, and cleave proteins to peptides (Ronci et al., 2008, O'Rourke et al., 2015, Fowler et al., 2013). For research targeting nucleotides, lipids, or peptides without primary amines, of which formalin does not form crosslinks, it is possible to apply the samples without such steps. Organic solvents such as ethanol can also fix tissues by coagulation and precipitation of proteins. Fixation with organic solvents has less impact on MALDI-IMS analysis, but it dissolves lipids from tissues. Some of the first principal components detected by PCA were the same among the samples, but some were not. These findings suggest that researchers should select a fixation solution according to the object used for analysis. The selection of the appropriate matrix is also crucial; DHB and CHCA are suitable for imaging small organic compounds, such as lipids and peptides, respectively (Setou and Kurabe, 2011).

Decalcification with EDTA or TCA was better than with formic acid for maintaining the tissue structures. Bone marrow had peeled from trabecular bone surfaces using formic acid decalcification, which can occur during the preparation of sections (Prasad and Donoghue, 2013). Treatment with TCA is useful because of rapid one-step fixation and decalcification that can preserve antigens and tissue morphology (Athanasou et al., 1987). In this study, sections from TCA-treated samples were the most suitable to examine both histology and comprehensive MS images.

By performing metabolomics of TCA-treated samples from mouse bone with MALDI-IMS, we were able to identify biomolecules, including phosphocholine, an important biomolecule for bone mineralization (Roberts et al., 2007, Yadav et al., 2011, Stewart et al., 2006, Kvam et al., 1992, Stern and Vance, 1987). Phosphocholine can be cleaved by PHOSPHO1, a soluble phosphatase that is responsible for initiating hydroxyapatite crystal formation inside osteoblast-derived matrix vesicles (Roberts et al., 2007, Stewart et al., 2006). PHOSPHO1-R74X null mutant mice display skeletal and growth plate abnormalities and a decrease in growth rate (Yadav et al., 2011). Phosphocholine is one of the abundant phosphomonoesters in cartilage (Kvam et al., 1992), and low accumulation of phosphocholine in calvarial tissue compared with liver is consistent with the upregulation of PHOSPHO1 activity in calvaria, whose function reduces the levels of phosphocholine in chondrocytes and osteoblasts (Stern and Vance, 1987).

This study successfully detected biomolecules in bones using MALDI-IMS. Although analytical procedures and compositional adjustment on device performance require further development, MALDI-IMS appears to be a powerful tool to search for biomolecules in bones.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Mitsutoshi Setou from Hamamatsu University School of Medicine for his excellent suggestions. We are deeply grateful to the members of Center of Oral Clinical Examination, Hiroshima University Hospital, for their support.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Athanasou N.A., Quinn J., Heryet A., Woods C.G., McGee J.O. Effect of decalcification agents on immunoreactivity of cellular antigens. J. Clin. Pathol. 1987;40:874–878. doi: 10.1136/jcp.40.8.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonewald L.F. The amazing osteocyte. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:229–238. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillero-Pastor B., Eijkel G.B., Blanco F.J., Heeren R.M. Protein classification and distribution in osteoarthritic human synovial tissue by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry imaging. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015;407:2213–2222. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole L.M., Mahmoud K., Haywood-Small S., Tozer G.M., Smith D.P., Clench M.R. Recombinant “IMS TAG” proteins - a new method for validating bottom-up matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation ion mobility separation mass spectrometry imaging. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2013;27:2355–2362. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djidja M.C., Claude E., Snel M.F., Scriven P., Francese S., Carolan V., Clench M.R. MALDI-ion mobility separation-mass spectrometry imaging of glucose-regulated protein 78 kDa (Grp78) in human formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded pancreatic adenocarcinoma tissue sections. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:4876–4884. doi: 10.1021/pr900522m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler C.B., O'Leary T.J., Mason J.T. Toward improving the proteomic analysis of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2013;10:389–400. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2013.820531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravius S., Randau T.M., Casadonte R., Kriegsmann M., Friedrich M.J., Kriegsmann J. Investigation of neutrophilic peptides in periprosthetic tissue by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight imaging mass spectrometry. Int. Orthop. 2015;39:559–567. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano H., Masaki N., Hayasaka T., Watanabe Y., Masumoto K., Nagata T., Katou F., Setou M. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization imaging mass spectrometry revealed traces of dental problem associated with dental structure. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014;406:1355–1363. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-7075-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto T. Use of a new adhesive film for the preparation of multi-purpose fresh-frozen sections from hard tissues, whole-animals, insects and plants. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 2003;66:123–143. doi: 10.1679/aohc.66.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvam B.J., Pollesello P., Vittur F., Paoletti S. 31P NMR studies of resting zone cartilage from growth plate. Magn. Reson. Med. 1992;25:355–361. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910250215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire R., Desmons A., Tabet J.C., Day R., Salzet M., Fournier I. Direct analysis and MALDI imaging of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:1295–1305. doi: 10.1021/pr060549i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke M.B., Djordjevic S.P., Padula M.P. A non-instrument-based method for the analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human spinal cord via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation imaging mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2015;29:1836–1840. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers T.W., Neely B.A., Shao Y., Tang H., Troyer D.A., Mehta A.S., Haab B.B., Drake R.R. MALDI imaging mass spectrometry profiling of N-glycans in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded clinical tissue blocks and tissue microarrays. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad P., Donoghue M. A comparative study of various decalcification techniques. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2013;24:302–308. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.117991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S., Narisawa S., Harmey D., Millán J.L., Farquharson C. Functional involvement of PHOSPHO1 in matrix vesicle-mediated skeletal mineralization. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007;22:617–627. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronci M., Bonanno E., Colantoni A., Pieroni L., Di Ilio C., Spagnoli L.G., Federici G., Urbani A. Protein unlocking procedures of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues: application to MALDI-TOF imaging MS investigations. Proteomics. 2008;8:3702–3714. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley E.H., Wilson K.J., Yankeelov T.E., Johnson R.W., Gore J.C., Caprioli R.M., Matrisian L.M., Sterling J.A. Co-registration of multi-modality imaging allows for comprehensive analysis of tumor-induced bone disease. Bone. 2014;61:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setou M., Kurabe N. Mass microscopy: high-resolution imaging mass spectrometry. J. Electron Microsc. 2011;60:47–56. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfq079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C., Tian Y., Dong Z., Gao J., Gao Y., Jia X., Guo G., Wen X., Jiang C., Zhang X. The use of principal component analysis in MALDI-TOF MS: a powerful tool for establishing a mini-optimized proteomic profile. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. 2012;4:85–101. doi: 10.5099/aj120100085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauber J., MacAleese L., Franck J., Claude E., Snel M., Kaletas B.K., Wiel I.M., Wisztorski M., Fournier I., Heeren R.M. On-tissue protein identification and imaging by MALDI-ion mobility mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:338–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern P.H., Vance D.E. Phosphatidylcholine metabolism in neonatal mouse calvaria. Biochem. J. 1987;244:409–415. doi: 10.1042/bj2440409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A.J., Roberts S.J., Seawright E., Davey M.G., Fleming R.H., Farquharson C. The presence of PHOSPHO1 in matrix vesicles and its developmental expression prior to skeletal mineralization. Bone. 2006;39:1000–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav M.C., Simão A.M., Narisawa S., Huesa C., McKee M.D., Farquharson C., Millán J.L. Loss of skeletal mineralization by the simultaneous ablation of PHOSPHO1 and alkaline phosphatase function: a unified model of the mechanisms of initiation of skeletal calcification. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:286–297. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]