Abstract

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is a commonly occurring genetic disorder in children. Mutation in the NF1 gene has its implication in poor osteoblastic capabilities. We hypothesised that pamidronate will enhance the osteoblastic potential of the mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from lipofibromatosis tissue of children with congenital pseudarthrosis tibia (CPT) associated with NF1. In this study, bone marrow MSCs (BM MSCs) and CPT MSCs were obtained from three patients undergoing salvage surgeries/bone grafting (healthy controls) and those undergoing excision of the hamartoma and corrective surgeries respectively. The effects of pamidronate (0, 10 nM, 100 nM and 1 μM) on cell proliferation, toxicity and differentiation potential were assessed and the outcome was measured by staining and gene expression. Our outcome showed that CPT MSCs had more proliferation rate as compared to BM MSCs. All 3 doses of pamidronate did not cause any toxicity to the cells in both the groups. The CPT MSCs showed less differentiation with pamidronate compared to the healthy control MSCs. This was quantitated by staining and gene expression analysis. Therefore, supplementation with pamidronate alone will not aid in bone formation in patients diagnosed with CPT. An additional stimulus is required to enhance bone formation.

Keywords: Lipofibromatosis, Congenital pseudarthrosis tibia, Mesenchymal stem cells, Differentiation, Bone formation, Pamidronate

Highlights

-

•

First study demonstrating the differentiation potential of MSCs derived from the hamartoma using pamidronate

-

•

The CPT MSCs have lower osteogenic potential as compared to BM MSCs.

-

•

The osteoblastic response does not improve with the addition of pamidronate (1 μM) in CPT MSCs.

-

•

Pamidronate enhances osteogenic differentiation in normal BM MSCs.

1. Introduction

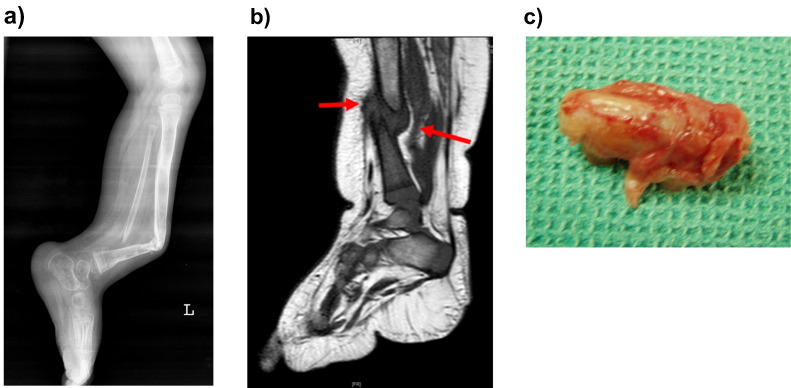

Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia (CPT) is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). NF1 is caused by a mutation in NF1 gene resulting in production of non-functional neurofibromin protein (Shen et al., 1996). This results in dysregulation of the Ras-Mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway which in turn affects the osteoblastic differentiation adversely (Cho et al., 2008). It is well known that there is generalized osteoporosis in NF1 affected individuals (Stevenson et al., 2007). One of the major phenotypic manifestations of NF1 which concerns orthopaedic surgeons is CPT (Schindeler and Little, 2008). These individuals present with fractures of the lower tibia and fibula at birth or early childhood (Fig. 1a, b). The fractured or bowed abnormal sclerotic and dysplastic bone is surrounded by a lipo-fibromatous hamartoma (Fig. 1c). This hamartoma is considered as the key pathology (Ippolito et al., 2000) and its complete removal is an essential part of treatment of CPT (Birke et al., 2010). The fundamental issue which has been the subject of investigations at the cellular level is the characteristics of the stem cells isolated from this hamartoma (Lee et al., 2011). Previous researchers have shown that these mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have poor capacity for osteoblastic differentiation and a high tendency for osteoclastogenesis (Cho et al., 2008). When fracture union is achieved with surgical means there is a tendency for bowing and re-fractures in the following years presumably due to the low level of osteogenesis in the affected bone (Shah et al., 2012), unless supported by internal and external splinting.

Fig. 1.

a: Lateral radiograph of a patient with congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia showing atrophic, bowed and narrow tibial bone and a false joint at the mid and distal third of the shaft. The fibula is also affected.

b: T1 weighted MR image showing hypointense pseudarthrosis with surrounding hypointense fibromatous tissue (red arrow).

c Excised specimen from the pseudarthrosis site including the bone ends and the surrounding fibrous hamartoma. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

There is a growing consensus in favour of using bisphosphonates to prevent fractures and re-fractures in congenital pseudarthrosis (Birke et al., 2010). The role of these nitrogen based compounds in preventing osteoclastic resorption is well known. Bisphosphonates cause apoptosis of osteoclasts and negatively affect the oncogenes (Ras, Rab and Rho) responsible for membrane trafficking and thus decrease osteoclast proliferation.

Preliminary animal and clinical studies show that co-treatment with systemic zoledronic acid, another bisphosphonate that improves net bone production, also promotes healing in cases of CPT by inhibiting the osteoclastic bone loss (Birke et al., 2010, Riebeling et al., 2002). While the effect of pamidronate on the osteoclasts is well understood, their influence on the osteoblasts in CPT is not clear. Pamidronate, a commonly used bisphosphonate has been shown to decrease viability and proliferation in human alveolar osteoblasts by researchers (Marolt et al., 2012). However, literature lacks studies on the effect of pamidronate on the osteoblastic potential of MSCs derived from fibrous hamartoma in CPT associated with NF1 as compared it those from bone marrow MSCs (BM MSCs).

This study aims to characterize the in vitro osteoblastic and adipogenic potentials of MSCs derived from lipo-fibromatous tissue isolated from CPT with clinical manifestations of neurofibromatosis using BM MSCs as control (from healthy patients), and also study the effect of pamidronate on cell viability, proliferation and differentiation potential.

2. Materials and methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. CPT and BM MSCs used in this experiment were isolated from the discarded tissue from children after informed consent from the parents.

2.1. Isolation of MSCs from fibrous hamartoma tissue

The discarded fibrous hamartoma tissue was harvested from three patients (2 females, one male with a mean age 5.3 years) with CPT undergoing excision of the hamartoma and corrective surgery. All of these patients were associated with café au lait spots of more than five in numbers and a histological fibrous hamartoma consistent with CPT. Tissue was collected in a 50 ml centrifuge tube containing DMEM/F12 (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA). The time taken to transport the sample to the lab was 1 h. The tissue was washed twice with phosphate buffered saline and minced which were then kept for overnight digestion (in CO2 incubator) using 1 mg/ml collagenase type II (Worthington Biochemicals, New Jersy, U.S.A.) in DMEM/F12. Following incubation, the cell suspension was filtered through 100 μm cell strainer (BD Falcon, Bedford, USA) and was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. Thus the MSCs from CPT was cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS.

2.2. Isolation of bone marrow MSCs (BM MSCs) from trabecular bone

The trabecular bone was harvested from three patients (3 males and mean age 5.6 years) undergoing deformity correction or bone grafting (healthy control). Discarded tissue was collected in a 50 ml centrifuge tube containing α-MEM media and transported to the lab for processing. BM MSCs (healthy control MSCs) from trabecular bone were isolated according to a previously published protocol (Sakaguchi et al., 2004). The cells were cultured in α-MEM with 10% FBS, 1% glutamine. The cells from both CPT and healthy control MSCs at passage 3 were used for the study.

2.3. MSC characterization

MSCs were characterized using cluster of differentiation (CD) markers by flow cytometry. MSCs specific markers such as CD73, and CD105 and negative markers CD14, CD34 and CD45 were used.

2.4. Cell proliferation assay

Pamidronate concentrations used in this study were selected based on the pharmacokinetics data provided in the drug data sheet. After infusion of clinical dose, maximum pamidronate concentration of 10 nM/ml of plasma will be achieved. Therefore we added 10 nM to 1 μM of pamidronate to the culture medium to assess cytotoxicity and effect on cell proliferation.

Cells were seeded at density of approximately 1500 cells/cm2. After 48 h of incubation the cells were treated with increasing concentration of pamidronate (no pamidronate, 10 nM, 100 nM and 1 μM) to check the effect of pamidronate on the cell proliferation. Assessment was done at three different time points namely 24, 48 and 72 h after incubation in triplicates. Cells were counted using Trypan Blue dye exclusion method.

2.5. Cytotoxicity test

The cytotoxic effect of pamidronate (0 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM and 1 μM) on cells (CPT and healthy control MSCs) was evaluated by MTT assay. Cells were cultured in 96 well plates (seeding density 25,000 cells/cm2) with complete media (DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS) and maintained in a CO2 Incubator. After 48 h of incubation, culture media was replaced with that containing pamidronate in 0 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM and 1 μM concentration. MTT assay was performed after further incubation of 24, 48 and 72 h in triplicates. MTT reagent (5 mg/ml) was added to the culture and incubated in dark condition for 5 h. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm with a reference filter at 620 nm using Microplate reader (Thermo Scientific).

2.6. Cell differentiation

MSCs were cultured in 24 well plates at a seeding density of approximately 4000 cells/cm2 and the cells were differentiated into osteoblast and adipocyte with and without pamidronate (1 μM). The osteogenic differentiation medium used was DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS, 10 nM Dexamethasone, 10 mM beta glycerophosphate, and 50 μg/ml Ascorbic acid, while the adipogenic differentiation medium was DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS, 10 μm 3- Isobutyl-1- methyl xanthine, 10 μg/ml Insulin, 100 μm Indomethacin and 1 μm dexamethasone. Differentiation was carried out for 28 days and was qualitatively assessed by Alizarin red (osteogenic) and Oil-O red (adipogenic) staining. Image J software was used to compute the percentage of area stained by a blinded observer. The analysis was repeated minimum three times and expressed as percentage area stained ± SD.

2.7. Real time PCR

Total RNA was isolated using TRI Reagent (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA) as per the manufacturer's protocol. Isolated total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). Template DNA was used in gene-specific RT-PCR The relative gene expression of osteogenic (RUNX2, ALPL, OSTEOCALCIN) and adipogenic (PPARγ, FABP4 and LPL) markers were calculated by ΔΔCt method and the results expressed in fold change. The samples were normalized with GAPDH (housekeeping gene) as the reference gene to calculate the ΔCt, which were further normalized with primary (day 0) MSCs as a sample control to calculate the ΔΔCt. The target gene expression level was quantified by 2− ΔΔCt.

2.8. Statistics

Analysis of variance and Mann Whitney test were used to compute the statistical significance between the untreated and drug treated groups. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant; graphs are represented as mean (SD).

3. Results

3.1. MSC characterization

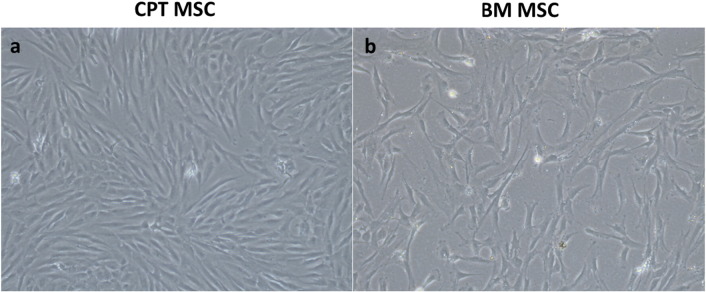

Phase contrast images of CPT MSC and healthy control MSC are shown in Fig. 2. Flow cytometry in all three cases showed that the cells isolated from CPT and healthy control had MSC specific cell surface markers. More than 95% of the cells were positive for CD73, CD105 and about 1% stained positive for the negative markers (CD14, CD34 and CD45) (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Phase contrast images of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) isolated from a) fibrous hamartoma and b) bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (healthy controls) showing spindle shaped morphology at 72 h after culture. Magnification × 10.

3.2. Cell proliferation

Compared to the untreated group (0 nM pamidronate), all the three doses (10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM) of pamidronate used in this study did not affect the proliferation in either the CPT or the healthy control MSCs groups (Fig. S2, S3). However when comparing CPT with healthy control MSCs, CPT MSCs have significantly (P < 0.001) higher proliferation rate than the healthy control MSCs at 72 h in all doses of pamidronate (Fig.3).

Fig. 3.

Represents the cell count at 24, 48 and 72 h in congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia (CPT) and BM MSCs (healthy controls). CPT MSCs were more proliferative than the healthy control MSCs and the difference in cell number at 72 h was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Error bar represents standard deviation.

3.3. MTT assay

Cytotoxicity as expressed by the formazan crystal colour change was not significant in CPT and healthy control MSCs at different concentrations of pamidronate (Fig.4).

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxic effect of pamidronate (0, 10 nM, 100 nM, 1 μM) on mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) isolated from a) congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia and b) healthy bone marrow MSCs. Error bar represents standard deviation.

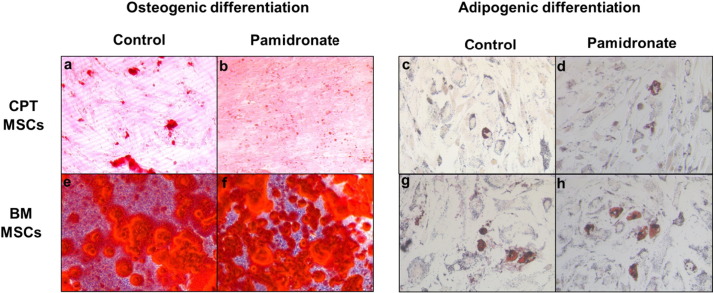

3.4. Differentiation potential

Osteoblastic and adipogenic differentiation of CPT and healthy control MSCs at 28 days of culture with 1 μM pamidronate was assessed both qualitatively by staining (Fig.5) and quantitatively by gene expression (Fig.6).

Fig. 5.

Effect of pamidronate (1 μM) on osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) isolated from a) congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia (CPT) (a–d) and healthy bone marrow MSCs (e–h). CPT MSCs treated with pamidronate stained less with Alizarin Red S (b) and Oil O Red (d) than the untreated (a & c), whereas BM MSCs with pamidronate stained more with Alizarin Red S (f) and Oil O Red (h) stain than the untreated group (e & g). Magnification × 20.

Fig. 6.

Effect of pamidronate (1 μM) on osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of congenital pseudarthrosis of tibia (CPT) and healthy bone marrow MSCs were quantitated using RT-PCR. Bar diagram represents the relative fold change of RUNX2 (a), ALPL (b) and osteocalcin (c), PPAR- γ (d & e), FABP4 (f & g) and LPL (h & i) genes in CPT and healthy control MSCs treated with and without pamidronate (1 μM). Quantitative analysis was performed in triplicate and gene expression was normalized against the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Expression of ALPL and PPAR- γ in the healthy bone marrow MSCs with pamidronate was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than the untreated group.

RUNX2 –Runt related transcription factor 2, ALPL – alkaline phosphatase, PPAR- γ - Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, FABP4- fatty-acid-binding proteins, LPL- Lipoprotein lipase.

As shown in Fig. 5, CPT MSCs were stained 5% ± 1 with Alizarin Red S in the untreated (5a) and 2.33% ± 0.68 in the pamidronate treated (5b) groups; while Oil Red O stained 9.8% ± 1.9 and 6.46% ± 1.96 in the untreated (5c) and treated (5d) groups respectively. In the healthy control MSCs, Alizarin Red S was stained 81% ± 7 and 81.5% ± 1.5 in the untreated (5e) and treated (5f) groups respectively. While Oil Red O was quantified to be 12.4% ± 3.1 and 15.4% ± 5.6 in the untreated (5 g) and treated (5 h) groups respectively.

3.5. Real time PCR

Expression of osteoblast (Runx-2, alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin) and adipocyte (PPAR-γ, FABP4 and LPL) specific genes were quantified by real time PCR (Fig. 6). Expression of Runx-2 and alkaline phosphatase with pamidronate was decreased by 2.2 fold and 1.7 fold respectively and the osteocalcin expression was decreased by 9.6 fold in CPT MSCs treated with pamidronate than the untreated group. In contrast, healthy control MSCs treated with pamidronate showed that the expression of Runx-2, alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin were up-regulated by 2.53, 7.7, and 6.5 folds respectively than the untreated group. Expression of alkaline phosphatase by the healthy control MSCs with pamidronate was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than the untreated MSCs.

Adipogenic differentiation of CPT cells were also minimally inhibited by pamidronate and the expression of PPAR-γ, FABP4 and LPL was reduced by 1.2, 2.02 and 1.7 folds respectively compared to the control (no pamidronate) group. However in the healthy control MSCs, the expression of PPAR-γ (1.7 fold), FABP4 (1.2 fold) and LPL (1.43 fold) were increased in the pamidronate group. Except for PPAR-γ, none of these outcomes were statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Qualitative and quantitative analysis showed that pamidronate enhanced the differentiation of healthy control MSCs into osteogenic and adipogenic lineage marginally. However in CPT MSCs the presence of pamidronate inhibited the differentiation into both lineages, more so in osteoblastic lineage. Thus when comparing the results of CPT MSCs with healthy control MSCs, the latter showed higher osteogenic and adipogenic potential.

4. Discussion

The therapeutic effects of bisphosphonates in preventing osteoporosis by inhibiting osteoclastic activity have been demonstrated experimentally and clinically. Bisphosphonates also induce apoptosis of osteoclasts by negatively regulating the Ras activity (Benford et al., 2001). Due to their anti-catabolic properties they are being considered for medical treatment of CPT (Birke et al., 2010). Clinically CPT is characterized by decreased bone formation and remodelling at the affected part of the tibia. In addition to this, there is resorption of bone in the affected area and eventual pseudarthrosis. It has been shown that supplementation with exogenous bone morphogenetic protein does not have the desired effect in healing the pseudarthrosis (Lee et al., 2006).

The conventional surgical treatment for CPT includes stimulation of bone formation by autologous bone grafting (Shah et al., 2012). In the recent years, pamidronate and zoledronate are the drugs used to supplement surgery. The therapeutic effect is mainly due to its anti-osteoclastic activity. There is no proof that bisphosphonates has an anabolic effect on CPT similar to normal bone (Gou et al., 2014, Pan et al., 2004).

In this study, the cells were treated with increasing concentration of pamidronate (0, 10 nM, 100 nM and 1 μM). None of these were toxic to the cells in both healthy control and CPT MSCs as evidenced by MTT and cell proliferation. Pamidronate at 1 μM was used finally as it would enhance osteoblastic differentiation of CPT MSCs. This choice was supported by Marolt et al. (2012) where 1 μM of pamidronate showed maximum alkaline phosphatase activity compared to 10 nM and 100 nM. This dosage was also selected based on literature and taking into consideration reports of cell toxicity in concentrations above 3 μM (Marolt et al., 2012). In the study by Wassen et al. healthy bone marrow MSCs were used and he found that higher concentration of pamidronate (10− 5) decreased the osteoblastic differentiation while at lower concentration (10− 9) increased osteogenic differentiation (Wassen et al., n.d.). In our study it was observed that the proliferation rate of CPT MSCs was higher in all dosages of pamidronate but with a decreased ability to differentiate to osteogenic and adipogenic lineages. This decrease in the differentiation was not significant when compared to healthy control MSCs. Pamidronate concentration at 1 μM increased the osteogenic differentiation of healthy control bone marrow MSCs as quantified by Alizarin Red S staining and gene expression.

In CPT the fibrous hamartoma around the affected site has been considered as the key pathology. The progenitor cells derived from this hamartoma have been shown to have cell surface markers similar to MSCs. However, on differentiation they tend to have a lower osteoblastic potential (Cho et al., 2008, Lee et al., 2011). The first phase of our study confirmed that the progenitor cells isolated from the fibrous hamartoma had the characteristic cell surface markers CD 73, CD105 and lacked CD 45 and CD 34 expression. These findings were similar to those of healthy control MSCs derived from the trabecular bone. Other authors have also isolated MSC like cells from fibrous hamartoma (Cho et al., 2008, Lee et al., 2011) but have not done a functional analysis by looking for multi-lineage differentiation.

One of the defining features of MSCs is to differentiate into osteogenic, adipogenic and chondrogenic lineages. We attempted to differentiate the CPT hamartoma MSCs to osteogenic and adipogenic lineages and compared the output with healthy control MSCs from trabecular bone. Our study showed that CPT MSCs were capable of differentiating into both adipogenic and osteogenic lineages. When compared to the healthy control MSCs, the adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation however was lower in CPT MSCs. This establishes the poor ability to differentiate into bone as a characteristic of the progenitor cells in hamartoma (Andersen, 1973) and is probably a key factor in the development of pseudarthrosis. This observation is similar to the work by Granchi et al. who found poor osteogenic differentiation in the local bone marrow at the affected site as compared to the iliac crest (Granchi et al., 2012). However there are no studies that have differentiated MSCs derived from the hamartoma and shown poor osteoblastic differentiation with pamidronate.

Studies have shown that the osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of bone marrow is enhanced by bisphosphonates (Casado-Díaz et al., 2013). Along with its osteoclastic activity, this is a major reason for pamidronate having an anabolic effect on bone formation. If pamidronate was to have a similar effect on the affected tibia in CPT, then one could postulate that the therapeutic advantage of pamidronate could be extended to an incipient fracture or an existing pseudarthrosis rather than a purely supportive role following surgery.

In our study we found that pamidronate at a dose of 1 μM increased the differentiation to both bone and adipose in healthy control MSCs, thus demonstrating its anabolic effect. This response was not seen in CPT MSCs which continued to have significantly higher proliferation rates occurring at the expense of lower differentiation to adipose and bone when compared to the group without pamidronate and when compared to healthy control MSCs. This was further evaluated by performing gene expression studies which showed low expression of alkaline phosphatase (osteogenic marker) and PARR (adipogenic marker). There are no previous studies on the hamartoma tissue highlighting these findings.

We propose that the formation of periosteal hamartoma in congenital pseudarthrosis is due to abnormally high proliferation associated with poor differentiation capability of mesenchymal stem cells (El-Hoss et al., 2012) residing in the local periosteum due to non-functional negative regulation of Ras signalling pathway in neurofibromatosis (Abramowicz and Gos, 2013). Bisphosphonates should support the differentiation by regulating the Ras protein in BM MSCs (von Knoch et al., 2005). Our experiments show that this is not taking place in the MSCs derived from periosteal hamartoma. From our study we conclude that pamidronate has no role in increasing bone formation in the affected area of CPT. However, based on the previous studies, it may have a role in preventing resorption due to its osteoclastic activity. The clinical implication of this finding is that pamidronate alone will not help in healing of a fracture hamartoma or remodelling of a severely affected bone. An additional stimulus such as an autologous bone graft which provides BM MSCs to the affected site is mandatory to achieve good union and remodelling.

There are few limitations in our study. We have characterized the cells isolated from the fibrous hamartoma by flow cytometry. The cells shared similar cell surface markers expressed in the bone marrow derived MSCs. The cells were also able to differentiate in to osteo and adipo lineages. This suggests that the isolated cells from CPT are progenitor cells. However we have not looked at other parameters such as maintenance of self-renewal and population doublings which distinguishes progenitor cells from MSCs. Our experiments also had a limitation in that they were performed in the absence of hydroxyapatite. In vivo, the pamidronate binds to hydroxyapatite in the bone and thus its effective concentration available to the periosteal MSCs may have been much lower than the in vitro experiment. Further experiments in the presence of calcium discs as carried out by Schindler et al. should be performed (Schindeler and Little, 2005). However this does not alter the conclusion that pamidronate doesn't provide an anabolic stimulus to osteoblasts.

5. Conclusion

The CPT MSCs have a lower osteogenic potential than healthy control MSCs. Unlike healthy control MSCs they do not show an osteoblastic response to pamidronate in the dose of 1 μM. The fracture of CPT thus requires an exogenous stimulus for osteogenesis.

Funding

This study was funded by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India (Grant number BT/IN/DENMARK/02/PDN2011).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Centre for Stem Cell Research, a unit of inStem, Bengaluru for providing laboratory facility for carrying out the study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.bonr.2016.10.003.

Contributor Information

Vrisha Madhuri, Email: madhuriwalter@cmcvellore.ac.in.

Smitha Elizabeth Mathew, Email: smithbeth@yahoo.com.

Karthikeyan Rajagopal, Email: karthikeyan.rr@gmail.com.

Sowmya Ramesh, Email: sowmyar@cmcvellore.ac.in.

B Antonisamy, Email: antoni@cmcvellore.ac.in.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Fig. 1 (Fig. S1) Characterization of MSCs isolated from CPT and BM using markers specific for MSCs by flow cytometry. CPT MSCs shows similar surface markers expression. Both CPT and BM MSCs stained > 95% positive for CD 73 and CD105, and stained negative for CD14, CD34 and CD45. M1 and M2 in the histogram represent the fluorescent intensity of unstained and stained cells respectively.

Supplementary figure (Fig. S2) Graphs represents the average cell number (N = 3) obtained after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment with and without pamidronate in mesenchymal stem cells isolated from congenital pseudoarthrosis patient (CPT).

Supplementary figure (Fig. S3) Graphs represents the average cell number (N = 3) obtained after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment with and without pamidronate in mesenchymal stem cells isolated from bone marrow.

References

- Abramowicz A., Gos M. Neurofibromin in neurofibromatosis type 1-mutations in nf1gene as a cause of disease. Dev. Period Med. 2013;18:297–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen K.S. Radiological classification of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1973;44:719–727. doi: 10.3109/17453677308989112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benford H. Visualization of bisphosphonate-induced caspase-3 activity in apoptotic osteoclasts in vitro. Bone. 2001;28:465–473. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birke O. Preliminary experience with the combined use of recombinant bone morphogenetic protein and bisphosphonates in the treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia. J. Child. Orthop. 2010;4:507–517. doi: 10.1007/s11832-010-0293-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casado-Díaz A. Risedronate positively affects osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stromal cells. Arch. Med. Res. 2013;44:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho T.-J. Biologic characteristics of fibrous hamartoma from congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2008;90:2735–2744. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hoss J. A murine model of neurofibromatosis type 1 tibial pseudarthrosis featuring proliferative fibrous tissue and osteoclast-like cells. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;27:68–78. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou W. Controlled delivery of zoledronate improved bone formation locally in vivo. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granchi D. A regenerative approach for bone repair in congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia associated or not associated with type 1 neurofibromatosis: correlation between laboratory findings and clinical outcome. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:306–314. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.627916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito E. Pathology of bone lesions associated with congenital pseudarthrosis of the leg. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 2000;9:3–10. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee F.Y.-I. Treatment of congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7 (rhbmp-7) JBJS Case Connector. 2006;627-633 doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D.Y. Disturbed osteoblastic differentiation of fibrous hamartoma cell from congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia associated with neurofibromatosis type i. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2011;3:230–237. doi: 10.4055/cios.2011.3.3.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marolt D. Effects of pamidronate on human alveolar osteoblasts in vitro. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012;70:1081–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan B. The nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate, zoledronic acid, increases mineralisation of human bone-derived cells in vitro. Bone. 2004;34:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riebeling C. The bisphosphonate pamidronate induces apoptosis in human melanoma cells in vitro. Br. J. Cancer. 2002;87:366–371. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi Y. Suspended cells from trabecular bone by collagenase digestion become virtually identical to mesenchymal stem cells obtained from marrow aspirates. Blood. 2004;104:2728–2735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindeler A., Little D.G. Osteoclasts but not osteoblasts are affected by a calcified surface treated with zoledronic acid in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;338:710–716. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindeler A., Little D.G. Recent insights into bone development, homeostasis, and repair in type 1 neurofibromatosis (nf1) Bone. 2008;42:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah H. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the tibia: Management and complications. Indian J. Orthop. 2012;46:616. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.104184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen M.H. Molecular genetics of neurofibromatosis type 1 (nf1) J. Med. Genet. 1996;33:2–17. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson D.A. Bone mineral density in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Pediatr. 2007;150:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Knoch F. Effects of bisphosphonates on proliferation and osteoblast differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6941–6949. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassen M. et al. Effects of Bisphosphonates on Osteoblast Differentiation In Vitro. 52nd Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Society. Paper No: 1639.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1 (Fig. S1) Characterization of MSCs isolated from CPT and BM using markers specific for MSCs by flow cytometry. CPT MSCs shows similar surface markers expression. Both CPT and BM MSCs stained > 95% positive for CD 73 and CD105, and stained negative for CD14, CD34 and CD45. M1 and M2 in the histogram represent the fluorescent intensity of unstained and stained cells respectively.

Supplementary figure (Fig. S2) Graphs represents the average cell number (N = 3) obtained after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment with and without pamidronate in mesenchymal stem cells isolated from congenital pseudoarthrosis patient (CPT).

Supplementary figure (Fig. S3) Graphs represents the average cell number (N = 3) obtained after 24, 48 and 72 h treatment with and without pamidronate in mesenchymal stem cells isolated from bone marrow.