Abstract

Biomphalaria snails are instrumental in transmission of the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. With the World Health Organization's goal to eliminate schistosomiasis as a global health problem by 2025, there is now renewed emphasis on snail control. Here, we characterize the genome of Biomphalaria glabrata, a lophotrochozoan protostome, and provide timely and important information on snail biology. We describe aspects of phero-perception, stress responses, immune function and regulation of gene expression that support the persistence of B. glabrata in the field and may define this species as a suitable snail host for S. mansoni. We identify several potential targets for developing novel control measures aimed at reducing snail-mediated transmission of schistosomiasis.

Biomphalaria glabrata is a fresh water snail that acts as a host for trematode Schistosoma mansoni that causes intestinal infection in human. This work describes the genome and transcriptome analyses from 12 different tissues of B glabrata, and identify genes for snail behavior and evolution.

The fresh water snail Biomphalaria glabrata (Lophotrochozoa, Mollusca) is of medical relevance as this Neotropical gastropod contributes as intermediate host of Schistosoma mansoni (Lophotrochozoa, Platyhelminthes) to transmission of the neglected tropical disease human intestinal schistosomiasis1. Penetration by an S. mansoni miracidium into B. glabrata initiates a chronic infection in which the parasite alters snail neurophysiology, metabolism, immunity and causes parasitic castration such that B. glabrata does not reproduce but instead supports generation of cercariae, the human-infective stage of S. mansoni. The complex molecular underpinnings of this long term, intimate parasite-host association remain to be fully understood. Patently infected snails release free-swimming cercariae that penetrate the skin of humans that they encounter in their aquatic environment. Inside the human host, S. mansoni matures to adult worms that reproduce sexually in the venous system surrounding the intestines, releasing eggs, many of which pass through the intestinal wall and are deposited in water with the feces. Miracidia hatch from the eggs and infect another B. glabrata to complete the life cycle. Related Biomphalaria species transmit S. mansoni in Africa. Schistosomiasis is chronically debilitating. Estimates of disease burden indicate that disability-adjusted life years lost due to morbidity rank schistosomiasis second only to malaria among parasitic diseases in impact on global human health2.

In the absence of a vaccine, control measures emphasize mass drug administration of praziquantel (PZQ), the only drug available for large-scale treatment of schistosomiasis3. Schistosomes, however, may develop resistance and reduce the effectiveness of PZQ4. Importantly, PZQ treatment does not protect against re-infection by water-borne cercariae released from infected snails. Snail-mediated parasite transmission must be interrupted to achieve long-term sustainable control of schistosomiasis5. The World Health Organization has set a strategy that recognizes both mass drug administration and targeting of the snail intermediate host as crucial towards achieving global elimination of schistosomiasis as a public health threat by the year 2025 (ref. 6). This significant goal provides added impetus for detailed study of the biology of B. glabrata.

Here we characterize the B. glabrata genome and describe biological properties that likely afford the snail’s persistence in the field, a prerequisite for schistosome transmission, and that may shape B. glabrata/S. mansoni interactions, including aspects of immunity and gene regulation. These efforts, we anticipate, will foster developments to interrupt snail-mediated parasite transmission in support of schistosomiasis elimination.

Results

Genome sequencing and analysis

The B. glabrata genome has an estimated size of 916 Mb (ref. 7) and comprises eighteen chromosomes (Supplementary Figs 1–3; Supplementary Note 1). We assembled the genome of BB02 strain B. glabrata8 (∼78.5 × coverage) from Sanger sequences (end reads from ∼136 kbp BAC inserts8), 454 sequences (short fragments, mate pairs at 3 and 8 kbp) and Illumina paired ends (300 bp fragments; Supplementary Data 1). Automated prediction (Maker 2)9 yielded 14,423 gene models (Methods). A linkage map was used to assign genomic scaffolds to linkage groups (Supplementary Note 2; Supplementary Data 2). We mapped transcriptomes (Illumina PE reads) from 12 different tissues of BB02 snails (Methods; Supplementary Data 1) onto the assembly to aid gene annotation. The pile up of reads revealed polymorphic transcripts (containing single nucleotide variants; SNV), that were correlated through KEGG10 analyses with metabolic pathways represented in the predicted proteome and the secretome (Supplementary Figs 4–7; Supplementary Note 3; Supplementary Data 7–8). Combined with delineation of organ-specific patterns of gene expression (Supplementary Figs 8 and 9; Supplementary Note 4; Supplementary Data 9), this provided potential molecular markers to help interpret B. glabrata’s responses to environmental insults and pathogens, including schistosome-susceptible mechanisms and resistant phenotypes.

Communication in an aquatic environment

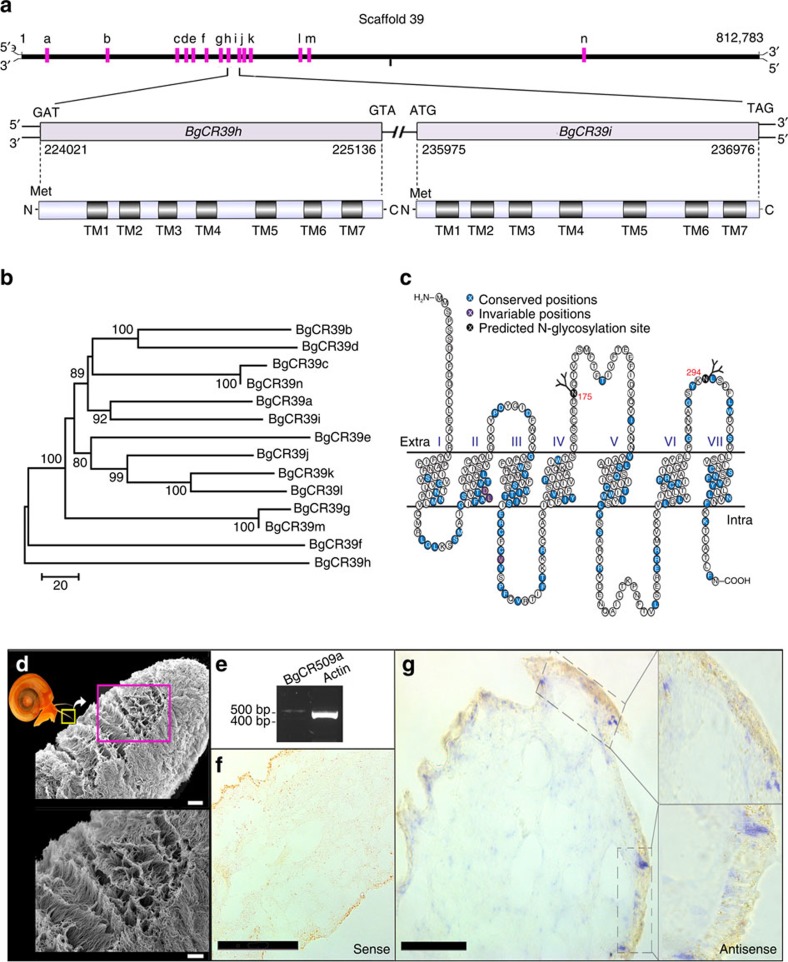

Aquatic molluscs employ proteins for communication; for example, Aplysia attracts conspecifics using water-soluble peptide pheromones11. We collected B. glabrata proteins from snail conditioned water (SCW) and following electrostimulation (ES), which induces rapid release of proteins. The detection by NanoHPLC-MS/MS of an orthologue of temptin, a pheromone of Aplysia12, among these proteins (Supplementary Note 5; Supplementary Data 10) suggests an operational pheromone sensory system in B. glabrata. To explore mechanisms for chemosensory perception, the B. glabrata genome was analysed for candidate chemosensory receptor genes of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) superfamily. We identified 241 seven transmembrane domain GPCR-like genes belonging to fourteen subfamilies, that cluster in the genome. RT–PCR and in situ hybridization confirmed expression of a GPCR-like gene within B. glabrata tentacles, known to be involved in chemosensation (Fig. 1). Use of chemical communication systems to interact with conspecifics may have a tradeoff effect by potentially exposing B. glabrata as a target for parasites (Supplementary Figs 10 and 11; Supplementary Note 6; Supplementary Data 11) and that can be developed to interfere with snail mate finding and/or host location by parasites.

Figure 1. Candidate chemosensory receptors of B. glabrata.

(a) LGUN_random_Scaffold39 contains fourteen candidate chemosensory receptor (CR) genes (BgCRa-n). Most encode seven-transmembrane domain G-protein-coupled receptor-like proteins, BgCRm and BgCRn are truncated to six-transmembrane domains. See Supplementary Data 11 for gene model identifiers. (b) Phylogenetic analysis (neighbour joining, scale bar represents amino-acid substitutions per site) of chemosensory receptors on LGUN_random_Scaffold39 (protein-level). (c) Schematic of receptor showing conserved and invariable amino acids, transmembrane domains I-VII; and location of glycosylation sites. (d) Scanning electron micrograph showing anterior tentacle, with cilia covering the surface. Scale bar, 20 μm (top); 10 μm (bottom). (e) RT–PCR gel showing amplicon for BgCR509a and actin from B. glabrata tentacle. (f,g) In situ hybridization showing sense (negative control) and antisense localization of BgCR509a mRNA in anterior tentacle section (purple). Scale bar (f): 100 μm; (g) 50 μm.

Stress and immunity

To persist in the environment, B. glabrata must manage diverse stressors, including heat, drought, xenobiotics, pollutants and pathogens including S. mansoni. Additional to previous reports of Capsaspora13 a single-cell eukaryote endosymbiont, we noted from the sequenced material an unclassified mycoplasma (or mollicute bacteria) and viruses (Supplementary Figs 12 and 13; Supplementary Notes 7 and 8; Supplementary Data 12). Pending further characterization of prevalence, specificity of association with B. glabrata, and impact on snail biology, these novel agents may find application in genetic modification of B. glabrata or control of snails through use of specific natural pathogens. Five families of heat-shock proteins (HSP): HSP20, HSP40, HSP60, HSP70 and HSP90 contribute to anti-stress response capabilities of B. glabrata. The HSP70 gene family is the largest with six multi-exon genes, five single-exon genes, and over ten pseudogenes (Supplementary Figs 14–17; Supplementary Note 9; Supplementary Data 13). In general, it is anticipated that future genome assemblies and continued annotation efforts can identify additional B. glabrata genes and provide updated gene models to reveal that some current pseudogenes are in fact intact functional genes. The existence of a single-exon HSP70 gene, however, was independently confirmed by sequence obtained from B. glabrata BAC clone (BG_BBa-117G16, Genbank AC233578, basepair interval 49686-51425) and this supports the notion that prediction of single exon gene models for several HSP70 genes from the current genome assembly is accurate. Retention of HSP genes in B. glabrata embryonic (Bge) cells, the only available molluscan cell line14, enables in vitro investigation of anti-stress and pathogen responses involving B. glabrata HSPs (Supplementary Figs 18–22; Supplementary Note 10; Supplementary Data 14). In addition, B. glabrata has about 99 genes encoding haem-thiolate enzymes (CYP superfamily) toward detoxifying xenobiotics, with representation of all major animal cytochrome P450 clans. Eighteen genes of the mitochondrial clan suggest that molluscs, like arthropods, but unlike vertebrates, also utilize mitochondrial P450s for detoxification15. Tissue-specific expression (for example, four transcript sequences uniquely in ovotestis) suggests that 15 P450 genes serve specific biological processes. These findings indicate potential for rational design of selective molluscicides, for example, by inhibiting unique P450s or by activation of the molluscicide only by B. glabrata-specific P450s (Supplementary Note 11; Supplementary Data 16).

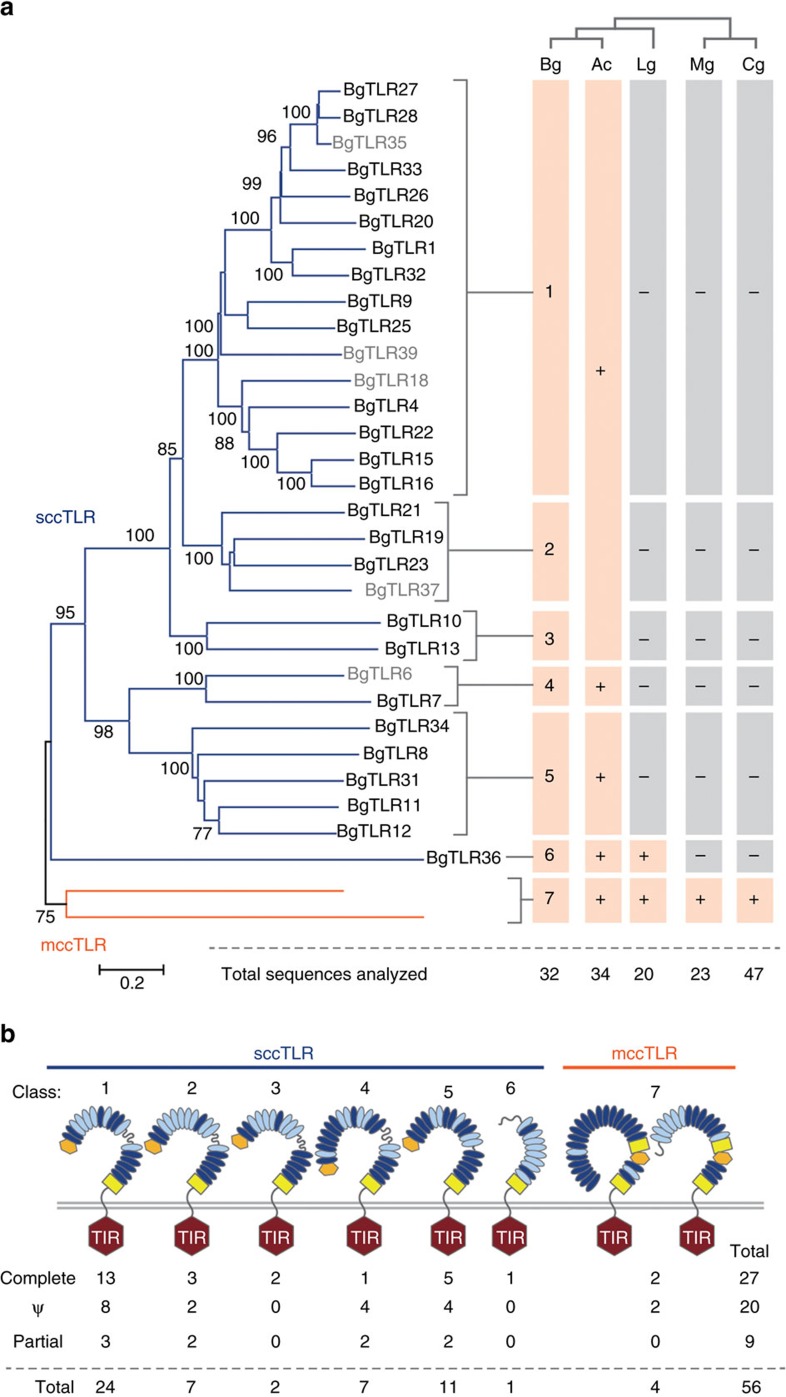

Biomphalaria glabrata employs pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)16 to detect pathogens and regulate immune responses. These include 56 Toll-like receptor (TLR) genes, of which 27 encode complete TLRs (Fig. 2; Supplementary Note 12; Supplementary Data 17), associated with a signaling network for transcriptional regulation through NF-κB transcription factors (Supplementary Fig. 23; Supplementary Note 13; Supplementary Data 18). Like other lophotrochozoans, B. glabrata shows expansion of TLR genes relative to mammals and insects which have ∼10 TLRs17. Other PRRs include eight peptidoglycan recognition-binding proteins (PGRPs), and a single Gram-negative binding protein (GNBP; Supplementary Note 12; Supplementary Data 17). A prominent category of B. glabrata PRRs consists of fibrinogen-related proteins (FREPs), plasma lectins that are somatically mutated to yield unique FREP repertoires in individual snails18. Our analyses revealed that this PRR diversity is generated from a limited set of germline sequences comprising 20 FREP genes with two upstream IgSF domains preceding an fibrinogen (FBG)-like domain, and four FREP genes encoding one immunoglobulin (IgSF) domain and one C-terminal FBG-like domain, including one gene with an N-terminal PAN_AP domain. FREP genes cluster in the genome, often accompanied by partial FREP-like sequences (Supplementary Figs 24–27; Supplementary Note 14). A proteomics level study indicated that S. mansoni resistance in B. glabrata associates with expression of parasite-binding FREPs of particular gene families, as well as GREP (galectin-related protein), FREP-like lectins that instead of a C-terminal FBG domain contain a galectin domain19 (Supplementary Figs 18,19; Supplementary Note 10; Supplementary Data 15). Further analyses yielded novel aspects of B. glabrata immune capabilities. We identified several cytokines, including twelve homologs of IL-17, four MIF homologs, and eleven TNF sequences (Supplementary Note 12; Supplementary Data 17). Biomphalaria glabrata possesses gene orthologs of complement factors that may function to opsonize pathogens (Supplementary Figs 28 and 29; Supplementary Note 15, Supplementary Data 19).

Figure 2. TLR genes in B. glabrata.

(a) Analysis of the (complete) TIR domains from BgTLRs identified seven classes (neighbour-joining tree, scale bar represents amino-acid substitutions per site). Bootstrap values shown for 1,000 replicates. Comparisons included TLRs from A. californica (Ac), L. gigantea (Lg), Mytilus galloprovincialis (Mg) and C. gigas (Cg). The presence or absence of orthologues of each class in each molluscan species is indicated. A representative of the B. glabrata class 1/2/3 clade is present within A. californica, but is independent of the B. glabrata TLR classes (indicated by the large pink box). Grey font indicates pseudogenes or partial genes. (b) B. glabrata has both single cysteine cluster (scc; blue line)- and multiple cysteine cluster (mcc; orange line) TLRs. Domain structures are shown for BgTLR classes. BgTLRs consist of an LRRNT (orange hexagon), a series of LRRs (ovals), a variable region (curvy line), LRRCT (yellow box), and transmembrane domain, and an intracellular TIR domain (hexagon). The dark blue ovals indicate well defined LRRs (predicted by LRRfinder57); light blue ovals are less confident predictions. Each of the two class 7 BgTLRs has a distinct ectodomain structure. The numbers of complete, pseudogenes (Ψ) and partial genes are indicated for each class.

We discovered an extensive gene set for apoptosis, a response that can regulate invertebrate immune defense20, including ∼50 genes encoding for Baculovirus IAP Repeat (BIR) domain-containing caspase inhibitors. The expansion of this gene family in molluscs (17 genes in Lottia gigantea, 48 in Crassostrea gigas), relative to other animal clades, suggests important regulatory roles in apoptosis and innate immune responses of molluscs21 (Supplementary Figs 30–32; Supplementary Note 16; Supplementary Data 20). We characterized a large gene complement to metabolize reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) that are generated by B. glabrata hemocytes to exert cell-mediated cytotoxicity toward pathogens, including schistosomes (Supplementary Fig. 33; Supplementary Note 17; Supplementary Data 21).

The antimicrobial peptide (AMP) arsenal of B. glabrata is surprisingly reduced compared to other invertebrate species (for example, bivalve molluscs have multiple AMP gene families22); our searches indicated only a single macin-type gene family, comprising six biomphamacin genes. However, B. glabrata does possess multigenic families of antibacterial proteins including two achacins, five LBP/BPIs, and 21 biomphalysins (Supplementary Fig. 34; Supplementary Note 18; Supplementary Data 22 and 23). While gaps in functional annotation limit our interpretation of B. glabrata immune function (Supplementary Note 19; Supplementary Data 24 and 25), our analyses reveal a multifaceted, complex internal defense system that must be evaded or negated by parasites such as S. mansoni to successfully establish infection.

Regulation of biological processes

Characterization of the regulatory mechanisms that rule gene expression and general biological functions is especially interesting because survival of B. glabrata relies on the capacity to quickly recognize, respond, and adapt to external and internal signals. In addition, a better understanding of parasite–host compatibility will be afforded by characterization of snail control mechanisms for gene expression and signalling pathways as possible targets for interference by S. mansoni to alter host physiology, including reproductive activities, to survive in B. glabrata23. Gene expression in B. glabrata is under epigenetic regulation24,25,26, we identified chromatin-modifying enzymes including class I and II histone methyltransferases, LSD-class and Jumonji-class histone demethylases, class I–IV histone deacetylases, and GNAT, Myst and CBP superfamilies of histone acetyltransferases. Biomphalaria has homologues of DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferases 1 and 2 (no homolog of DNMT3), as well as putative methyl-CpG binding domain proteins 2/3. In silico analyses predicted a mosaic type of DNA methylation, as is typical for invertebrates (Supplementary Figs 35–39; Supplementary Note 20; Supplementary Data 26). The potential role of DNA methylation in B. glabrata reproduction and S. mansoni interactions is reported in a companion paper27.

The B. glabrata genome also encodes the protein machinery for biogenesis of microRNA (miRNAs) to regulate gene expression (Supplementary Note 21; Supplementary Data 27). Two computational methods independently predicted the same 95 pre-miRNAs, encoding 102 mature miRNAs. Of these, 36 miRNAs were observed within our transcriptome data, another 53 miRNAs displayed ≥90% nucleotide identity with L. gigantea miRNAs. Bioinformatics predicted 107 novel pre-miRNAs unique to B. glabrata. Based on the analysis of binding thermodynamics and miRNA:mRNA structural features, several novel miRNAs were predicted to likely regulate transcripts involved in processes unique to snail biology, including secretory mucosal proteins and shell formation (biomineralization) that may present possible targets for control of B. glabrata (Supplementary Figs 40–67; Supplementary Note 21 and 22; Supplementary Data 28–33).

Periodicity of aspects of B. glabrata biology28 indicates likely control by circadian timing mechanisms. We identified seven candidate clock genes in silico, including a gene with strong similarity to the period gene of A. californica. Modification of expression of clock genes may interrupt circadian rhythms of B. glabrata and affect feeding, egg-laying and emergence of cercariae (Supplementary Note 23).

Neuropeptides expressed within the nervous system coordinate the complex physiology of B. glabrata, a simultaneous hermaphrodite snail. In silico searches identified 43 B. glabrata neuropeptide precursors, predicted to yield over 250 mature signalling products. Neuropeptide transcripts occurred in multiple tissues, yet some were most prominent within terminal genitalia (49%) and the CNS (56%), or even specific to the CNS, including gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and insulin-like peptides 2 and 3 (Supplementary Fig. 68; Supplementary Note 24; Supplementary Data 34–36). The reproductive physiology of hermaphroditic snails is also modulated by male accessory gland proteins (ACPs), which are delivered with spermatozoa to augment fertilization success29. The B. glabrata genome has sequences matching one such protein, Ovipostatin (LyAcp10), but none of the other ACPs identified in Lymnaea stagnalis30. Putatively, ACPs evolve rapidly and are taxon specific (Supplementary Fig. 69; Supplementary Note 25; Supplementary Data 34), such that they allow for specific targeting of reproductive activity for control measures.

A role of steroid hormones in reproduction of hermaphrodite snails with male and female reproductive organs remains speculative. Biomphalaria glabrata has a CYP51 gene to biosynthesize sterols de novo, yet we found no orthologs of genes involved in either vertebrate steroid or arthropod ecdysteroid biosynthesis. The lack of CYP11A1 suggests that B. glabrata cannot process cholesterol to make vertebrate-like steroids. The absence of aromatase (CYP19), required for the formation of estrogens, is particularly enigmatic as molluscs possess homologues of mammalian estrogen receptors. Characterization of snail-specific aspects of steroidogenesis may identify targets to disrupt reproduction towards control of snails. (Supplementary Fig. 70; Supplementary Note 26; Supplementary Data 37).

Eukaryotic protein kinases (ePKs) and phosphatases constitute the core of cellular signaling pathways, playing a central role in signal transduction by catalyzing reversible protein phosphorylation in non-linearly integrated networks. Schistosoma mansoni likely interferes with the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway to survive in B. glabrata23. Hidden Markov model searches on the predicted B. glabrata proteome identified 240 potential ePKs, encompassing all main types of animal ePKs (Supplementary Fig. 71; Supplementary Note 27). Similarity searches also identified 60 putative protein phosphatases comprising ∼36 protein Tyr phosphatases (PTPs) and ∼24 protein Ser/Thr phosphatases (PSPs) (Supplementary Figs 72–74; Supplementary Note 28). These sequences can be studied for understanding control of homeostasis, particularly in the face of environmental and pathogenic insults encountered by B. glabrata.

Bilaterian evolution

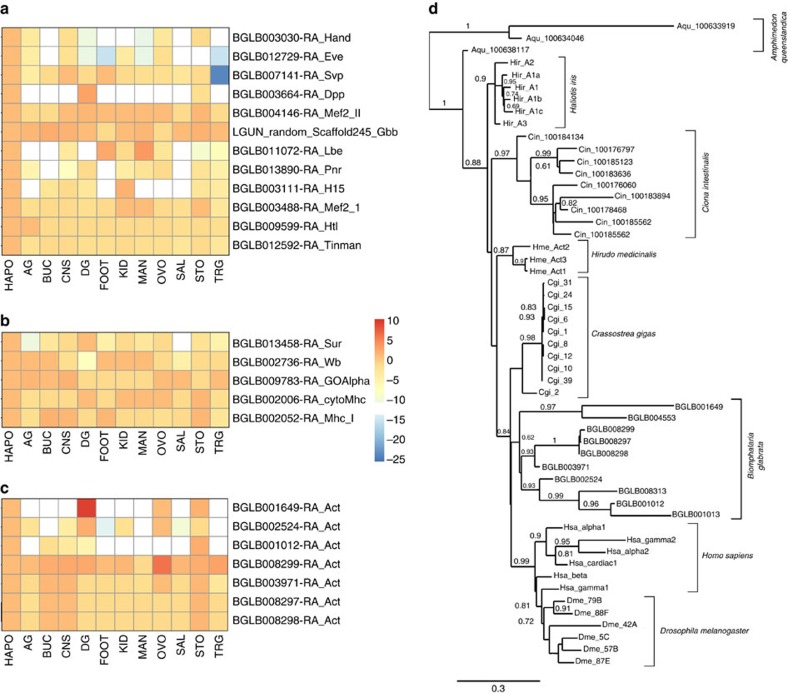

Genome study of B. glabrata can also provide new insights into evolution of bilaterian metazoa by increasing diversity of the relatively few lophotrochozoan taxa that have been characterized to date (that is, platyhelminths, leech, bivalve, cephalopod and polychaete)31,32,33,34,35. Comparison of similar biological features and gene expression patterns among lophotrochozoans, ecdysozoans and deuterostomes may indicate the evolutionary origin of conserved gene families and anatomical features. The prevalence in diverse taxa of metazoa, including molluscs, arthropods and chordates, of muscular heart-like organs that function to circulate blood or hemolymph, has led to the proposal that these structures evolved over evolutionary time from a primitive heart present in an urbilaterian ancestor. This hypothesis is supported by similarities in core genes for specification and differentiation of cardiac structures between insects (in particular Drosophila) and vertebrates36,37. To further develop this notion, we searched for molluscan cardiac-specification and -differentiation genes in the genome of B. glabrata. A previously characterized short cDNA sequence from snail heart RNA led to identification of BGLB012592 as the Biomphalaria ortholog of tin/Nkx2.5 (ref. 38). Similarity searches with Drosophila orthologues identified most of the core cardiac regulatory factors and structural genes in the B. glabrata genome (Supplementary Note 29; Supplementary Data 38), with enriched expression of these genes in cardiac tissues (Fig. 3). Pending confirmation of functional involvement of these core cardiac genes in heart formation, these results from a lophotrochozoan, in conjunction with ecdysozoans and deuterostomes, merit continued consideration of the presence of a primitive heart-like structure and in the urbilaterian ancestor.

Figure 3. Expression of cardiac genes and actin genes in B. glabrata tissues.

(a) Cardiac regulatory genes. (b) Cardiac structural genes. (c) Relative expression of actin genes in B. glabrata tissues. For (a–c), the score represents gene level aggregate of normalized FPKM counts for de novo assembled tissue transcripts, relative to expression levels in the heart/APO sample. The counts were scaled (with median read count as 0) to indicate expression intensity with red indicating highest, blue lowest. AG, Albumen gland; BUC, buccal mass; CNS, central nervous system; DG, digestive gland; FOOT, headfoot; HAPO, heart/APO; KID, kidney; MAN, mantle edge; OVO, ovotestes; SAL, salivary glands; STO, stomach; TRG, terminal genitalia. (d) Maximum Likelihood tree (Phylogeny.fr, scale bar represents amino-acid substitutions per site) showing phylogenetic relationships of actin genes, based on amino-acid sequence alignment (ClustalW). Biomphalaria -snail; Crassostrea gigas—oyster; Haliotis iris– abalone;, Hirudo medicinalis – leech (all lophotrochozoans); Amphimedon queenslandica, sponge, Prebilateria, ophotrochozoans), Drosophila melanogaster—fruit fly, Ecdysozoa), and the deuterostomes Ciona intestinalis, sea squirt; Homo sapiens, human. See Supplementary Note 31 for accession numbers.

We also investigated in molluscs, relative to insects and mammals, the evolution of the gene family of actins, conserved proteins that function in cell motility (cytoplasmic actins) and muscle contraction (sarcomeric actins)39. Previous study showed that cephalopod actin genes40, are more closely related to one another than to any single mammalian gene, an observation also made another mollusc Haliotis41 and for insect actins42. Thus, it has been proposed that actin diversification in arthropods, molluscs and vertebrates each occurred independently. However, it has not been determined whether different molluscan lineages independently underwent actin gene divergence, and few studies have analysed expression of mollusc actin genes in different tissues41,43. We identified ten actin genes in B. glabrata that are clustered across seven scaffolds to suggest that some of these genes arose through tandem duplication. Expression across all tissues indicates that four genes encode cytoplasmic actins (Fig. 3). Protein sequence comparisons placed all B. glabrata actins as most closely related to mammalian cytoplasmic rather than sarcomeric actins (Supplementary Note 30; Supplementary Data 39), a pattern also observed for all six actin genes of D. melanogaster44. The actin genes of B. glabrata and other molluscs were most similar to paralogs within their own genomes, rather than to other animal orthologs (Fig. 3). One interpretation is that actin genes diverged independently multiple times in molluscs, similar to an earlier hypothesis for independent actin diversification in arthropods and chordates42. Alternatively, a stronger appearance of monophyly than really exists may result if selective pressures due to functional constraints keep actin sequences similar within a genome, for example if the encoded proteins have overlapping functions.

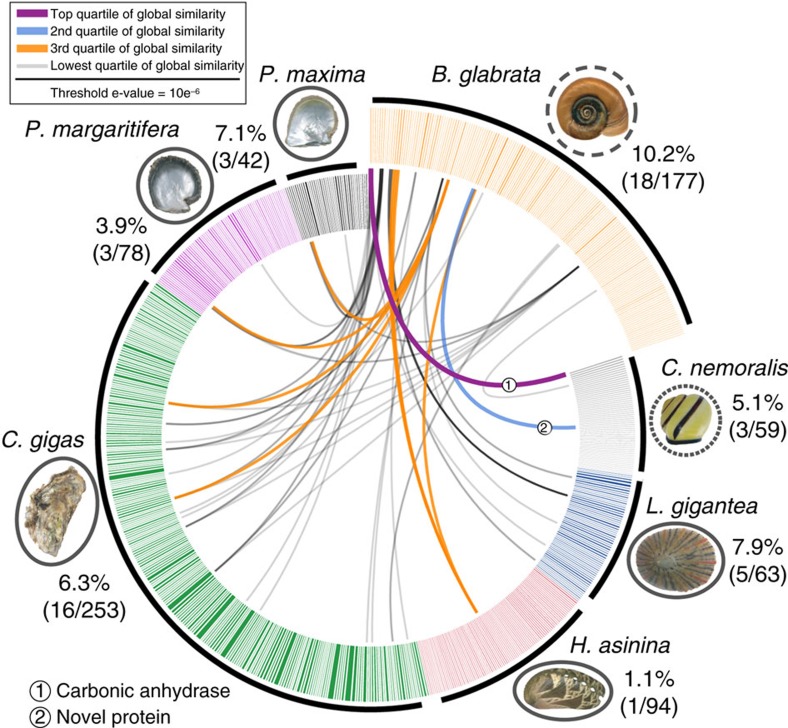

To gain insight into the diversification of mechanisms involved in biomineralization in molluscs, we analyzed the transcriptomic data for B. glabrata genes involved in biomineralization. Of 1,211 transcripts that were more than twofold upregulated in the mantle relative to other tissues, 34 shared similarity with molluscan sequences known to be involved in shell formation and biomineralization. Another 177 candidate sequences putatively involved in shell formation including 18 genes (10.2%) with similarity to sequences of shell forming secretomes of other marine and terrestrial molluscs were identified from the entire mantle transcriptome (Fig. 4). Highly conserved components of the molluscan shell forming toolkit include carbonic anhydrases and tyrosinases33 (Supplementary Fig. 75; Supplementary Note 31; Supplementary Data 40). In summary, this genome-level analysis of a subset of molluscan molecular pathways provides new insight into the evolutionary origins of bilaterian organs, gene families and genetic pathways.

Figure 4. Comparison of molluscan shell forming proteomes.

Circos diagram of 177 mantle-specific, secreted Biomphalaria gene products compared against shell forming proteomes of six other molluscs (BLASTp threshold ≤10e−6). Protein pairs that share sequence similarity in the top quartile are linked in purple, the second quartile is linked in blue, third quartile has orange links and lowest quartile of similarity has grey links. Species that occupy marine habitats are surrounded by a solid line, A finely dashed line identifies the terrestrial species Cepea nemoralis, the freshwater species B. glabrata has a coarse line. Percentages (and proportions in brackets) indicate the number of proteins that shared similarity with a Biomphalaria shell forming candidate gene. The width of each sector line around the ideogram is proportional to the length of that gene in basepairs. Photographs taken by DJ Jackson, with exception of photograph of C. gigas, by David Monniaux, distributed under a CC-A SA 3.0 license.

Repetitive landscape

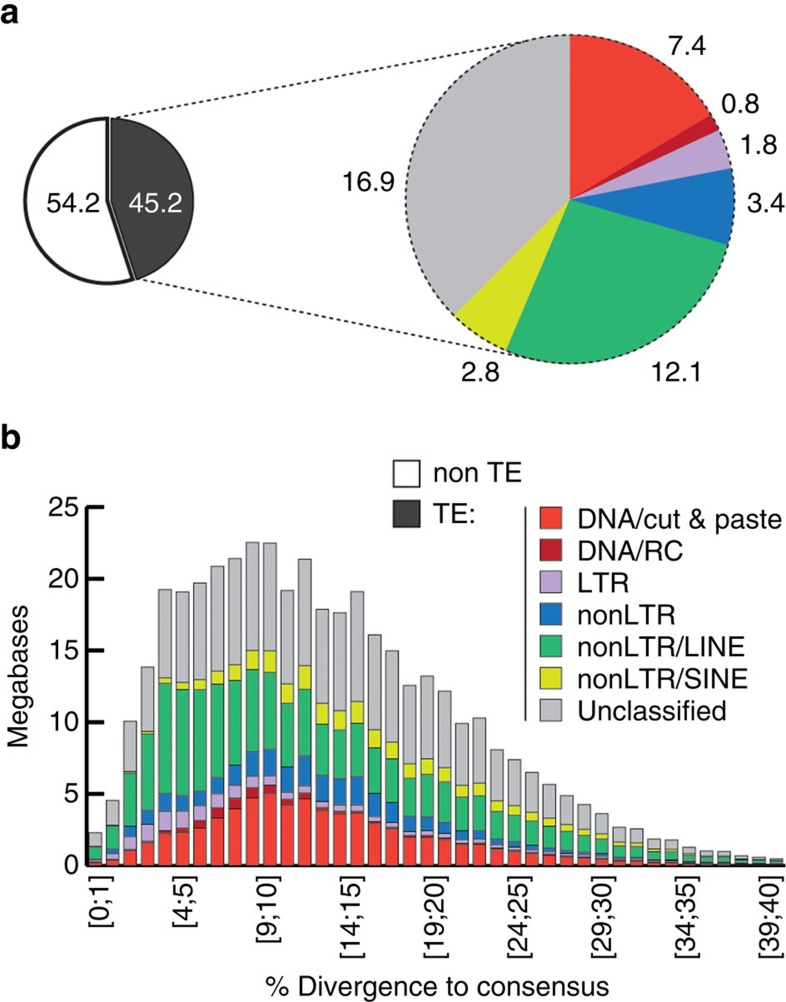

Repeat content analysis showed that 44.8% of the B. glabrata assembly consists of transposable elements (TEs; Fig. 5; Supplementary Figs 76-78; Supplementary Note 32; Supplementary Data 41), comparable to Octopus bimaculoides (43%)34 and higher than observed in other molluscs: Owl limpet, L. gigantea (21%)31; Pacific oyster, C. gigas (36%)32; Sea hare, A. californica (30%)45. The fraction of unclassified elements in B. glabrata was high (17.6%). Most abundant classified repeats were LINEs, including Nimbus46 (27% of TEs, 12.1% of the genome), and DNA TEs (17.7% of TEs, 8% of the genome). Long terminal repeats (LTRs) represented 6% of TEs (1.7% of the genome), and non-mobile simple repeats comprised 2.6% of the genome (with abundant short dinucleotide satellite motifs). Divergence analyses of element copy and consensus sequences indicated that DNA TEs were not recent invaders of the B. glabrata genome; no intact transposases were detected in the assembly. A hAT DNA transposon of B. glabrata (∼1,000 copies) has significant identity with SPACE INVADERS (SPIN) which horizontally infiltrated a range of animal species, possibly through host-parasite interactions47. Overall, our results reinforce a model in which diverse repeats comprise a large fraction of molluscan genomes.

Figure 5. Transposable element (TE) landscape of B. glabrata.

(a) Left: proportion (%) of the genome assembly annotated as TE (black). Right: TE composition by class (indicating % of the genome corresponding to each class). (b) Evolutionary view of TE landscape. For each class, cumulative amounts of DNA (in Mb) are shown as function of the percentage of divergence from the consensus (by bins of 1%, first one being ≥0 and <1; see Supplementary Note 32 for Methods). Percentage of divergence from consensus is used as a proxy for age: the older the invasion of the TE is, the more copies will have accumulated mutations (higher percentage of divergence, right of the graph; left of the graph: youngest elements showing little divergence from consensus). Note that the result of this analysis of assembled sequence does not exclude the likelihood that intact transposable elements are present in B. glabrata. Colors are as in a. RC, rolling circle.

Discussion

The genome of the Neotropical freshwater snail B. glabrata expands insights into animal biology by further defining the Lophotrochozoan lineage relative to Ecdysozoa and Deuterostomia. An important rationale for genome analysis of B. glabrata pertains to its role in transmission of S. mansoni in the New World. Most of the world’s cases of S. mansoni infection, however, occur in sub-Saharan Africa where other Biomphalaria species are responsible for transmission, most notably Biomphalaria pfeifferi. Likely due to a shared common ancestor, B. glabrata provides a good representation of the genomes of African Biomphalaria species48,49. At least 90% sequence identity was shared among 196 assembled transcripts collected from B. pfeifferi (Illumina RNAseq) and the transcriptome of B. glabrata (Supplementary Note 33; Supplementary Data 42–43). Accordingly, our analyses of the B. glabrata genome likely reveal biological features that define snail species of the genus Biomphalaria as effective hosts for transmission of human schistosomiasis. This work provides several inroads for control of Biomphalaria snails to reduce risks of schistosome (re)infection of endemic human populations, an important component of the WHO strategy aimed at elimination of the global health risks posed by schistosomiasis6. The following are among options that can be considered50. The genetic information uncovered may be applied to characterize and track the field distribution of snail populations that differ in effectiveness of parasite transmission. Targeting aspects of pheromone-based communication among Biomphalaria conspecifics may alter the mating dynamics of these snails and perhaps also to interfere with the intermediate host finding of larval schistosomes. Molluscicide design may be tailored to impact unique gene products and mechanisms for gene regulation, reproduction and metabolism toward selective control of Biomphalaria snails. Finally, genetic modification of determinants of intermediate host competence may alter schistosome transmission by Biomphalaria. In summary, this report provides novel details on the biological properties of B. glabrata, including several that may help determine suitability of B. glabrata as intermediate host for S. mansoni, and points to potential approaches for more effective control efforts against Biomphalaria to limit the transmission of schistosomiasis.

Methods

The genetic material used for sequencing the genome of the hermaphroditic freshwater snail Biomphalaria glabrata was derived from three snails of the BB02 strain (shell diameter 8, 10 and 12 mm, respectively), established at the University of New Mexico, USA from a field isolate collected from Minas Gerais, Brazil, 2002 (ref. 8). Using a genome size estimate of 0.9–1 Gb (ref. 7), we sequenced fragments (450 bp read length; 14.08 × coverage) and paired ends from 3 kb long inserts (8.12 × ) and 8 kb long inserts (2.82 × ) with reads generated on Roche 454 instrumentation, plus 0.06 × from bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) ends8 on the ABI3730xl. Reads were assembled using Newbler (v2.6)51. Paired end reads from a 300 bp insert library (53.42 × coverage) were collected using Illumina instrumentation and assembled de novo using SOAP (v1.0.5)52. The Newbler assembly was merged with the SOAP assembly using GAA53 (see Supplementary Data 1 for accession numbers of sequence data sets). Redundant contigs in the merged assembly were collapsed and gaps between contigs were closed through iterative rounds of Illumina mate-pair read alignment and extension using custom scripts. We removed from the assembly all contaminating sequences, trimmed vectors (X), and ambiguous bases (N). Short contigs (≤200 bp) were removed prior to public release. In the creation of the linkage group AGP files, we identified all scaffolds (145 Mb total) that were uniquely placed in a single linkage group (Supplementary Note 2; Supplementary Data 2). Note that because of low marker density, scaffolds could not be ordered or oriented within linkage groups. The final draft assembly (NCBI: ASM45736v1) is comprised of 331,400 scaffolds with an N50 scaffold length of 48 kb and an N50 contig length of 7.3 kb. The assembly spans over 916 Mb (with a coverage of 98%, 899 Mb of sequence with ∼17 Mb of estimated gaps). The draft genome sequence of Biomphalaria glabrata was aligned with assemblies of Lottia and Aplysia (http://biology.unm.edu/biomphalaria-genome/synteny.html) and deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database (Accession Number APKA00000000.1). It includes the genomes of an unclassified mollicute (Supplementary Note 7; accession numbers CP013128). The genome assembly was also deposited in Vectorbase54 (https://www.vectorbase.org/organisms/biomphalaria-glabrata). Computational annotation using Maker2 (ref. 9) yielded 14,423 predicted gene models, including 96.5% of the 458 sequences from the CEGMA core set of eukaryotic genes55. Total RNA was extracted from 12 different tissues/organs dissected from several individual adult BB02 B. glabrata snails (shell diameter 10–12 mm; between 2 and 10 snails per sample to obtain sufficient amounts of RNA). RNA was reverse transcribed using random priming, no size selection was done. Illumina RNAseq (paired ends) was used to generate tissue-specific transcriptomes for albumen gland (AG); buccal mass (BUC); central nervous system (CNS); digestive gland/hepatopancreas (DG/HP); muscular part of the headfoot (FOOT); heart including amebocyte producing organ (HAPO); kidney (KID); mantle edge (MAN); ovotestis (OVO); salivary gland (SAL); stomach (STO); terminal genitalia (TRG), see Supplementary Data 1 for accession numbers of sequence data sets. RNAseq data were mapped to the genome assembly (Supplementary Note 3). No formal effort was made to use the RNA-data to systematically enhance the structural annotation. VectorBase did, however, make this RNAseq data available in WebApollo56 such that the community could use these data to correct exon-intron junctions, UTRs, etc. through community annotation. All of these community-based updates have been incorporated and are available via the current VectorBase gene set. Repeat features were analyzed and masked (Supplementary Note 32; see Vectorbase Biomphalaria-glabrata-BB02_REPEATS.lib, Biomphalaria-glabrata-BB02_REPEATFEATURES_BglaB1.gff3.gz). Further methods and results are described in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

The sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in GenBank with the accession codes SRX005826, -27, -28; SRX008161, -2; SRX648260, -61, -62, -63, -64, -65, -66, -67, -68, -69, -70, -71; SRA480937; SRA480939; SRA480940; SRA480945; TI accessions2091872204-2092480271; 2104228958-2104243968; 2110153721-2118515136; 2181062043-2181066224; 2193113537-2193116528; 2204642410-2204763511; 2204820860-2204852286; 2213009530-2213057324; 2260448774-2260450167. Also see Supplementary Data 1. The assembly and related data are available from VectorBase, https://www.vectorbase.org/organisms/biomphalaria-glabrata. The Biomphalaria glabrata genome project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number APKA00000000.1

Additional information

How to cite this article: Adema, C. M. et al. Whole genome analysis of a schistosomiasis-transmitting freshwater snail. Nat. Commun. 8, 15451 doi: 10.1038/ncomms15451 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References

Sequence data sets

Biomphalaria glabrata linkage groups

Proteome InterProscan annotation

proteome KEGG/SNV mapping

Prediction of secreted proteins

fasta sequences of predicted secreted proteins (fasta)

secretome B. glabrata, Interproscan annotation

Pfam domain annotation of predicted secretome

Transcripts, tissue distribution

Secreted_proteins SCW&ES_Topblast_results

Predicted GPCR genes of Biomphalaria glabrata

Mycoplasma/Mollicute annotation

HSP annotation

GREPs bind to S.mansoni

HSP expression in Bge cell-line

Cytochrome P 450 (CYP) genes of B. glabrata.

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokines

TLR pathway signaling

Complement-like factors.

Apoptosome

REDOX genes

Antimicrobial factors

Antimicrobial factors expression profiles

Annotation unknown microarray features

Expression patterns of previous unknowns.

Epigenetic toolbox genes

miRNA and piRNA pathway factors

Conserved precursor miRNAs, Structural, location and thermodynamic

Conserved mature miRNAs B. glabrata and homologs

conserved precursor miRNAs tissue distribution in B. glabrata

Conserved miRNA target gene predictions

Novel miRNAs predictions

Novel predicted miRNA and target genes

Neuropeptides precursors and prepropeptides

neuropeptides, tissue distribution

Predicted bioactive cleavage products of neuropeptides

Steroidogenesis pathway genes

Cardiac regulatory and structural genes in B. glabrata

Biomphalaria glabrata actins

Biomineralization transcripts from B. glabrata mantle tissue.

Low-copy transposable elements (TE) abundance

Identity of 34 B. pfeifferi and B. glabrata sequence homologs

Sequence Identity of B. pfeifferi homologs to 162 B. glabrata genes from

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Newfeld for discussion of actin evolution; N. El Sayed and H. Tettelin for discussion of HSP annotation and expression. We acknowledge access to the Metafer microscopy system at the I. Robinson Research Complex, Harwell, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Oxon, UK (BBSRC Professorial Fellowship, grant number BB/H022597/1). Sequence characterization of the Biomphalaria glabrata genome was funded by NIH-NHGRI grant HG003079 to R.K.W., McDonnell Genome Institute, Washington University School of Medicine. Biomphalaria glabrata and Schistosoma mansoni were provided to some participating labs by the NIAID Schistosomiasis Resource Center (Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, MD) through NIH-NIAID Contract HHSN272201000005I for distribution through BEI Resources. C.M.A. and E.S.L. acknowledge NIH grant P30GM110907 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). Publication costs were contributed equally by McDonnell Genome Institute, Washington University School of Medicine and the COBRE Center for Evolutionary and Theoretical Immunology (CETI) which is supported by NIH grant P30GM110907 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). E.S.L. acknowledges NIH/NIAID ROI AI101438. J.M.B., H.D.A.-G and M.K. acknowledge NIH-NIAID R01-AI0634808. M.Y. acknowledges UK BBSRC (BB/H022597/1). G.O. acknowledges support from FAPEMIG (RED-00014-14, PPM-00189-13) and CNPq (304138/2014-2, 309312/2012-4). R.L.C. acknowledges CNPq (503275/2011-5). T.P.Y. acknowledges NIH/NIAID RO1AI015503. K.F.H. and M.T.S. acknowledge BBSRC (BB/K005448/1). B.G. acknowledges ANR JCJC INVIMORY (ANR-13-JSV7-0009). S.E. acknowledges NIAID contract HHSN272201400029C. J.M.K. acknowledges the Research Council for Earth and Life Sciences (A.L.W.; 819.01.007) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). R.M.C. acknowledges NIH GM061738 and support from the American Heart Association, Southwest Affiliate (14GRNT20490250). D.T. acknowledges NIH R25 GM075149. C.F. acknowledges NIH R01-GM077582. D.J.J. acknowledges D.F.G. JA2108/1-2. M.de S.G. acknowledges CNPq 479890/2013-7. K.M.B. and J.P.R. acknowledge NSERC 312221 and CIHR MOP74667. C.S.J., L.R.N., S.J., E.J.R., S.K. and A.E.L. acknowledge NC3R GO900802/1. K.K.B. and K.B.S. acknowledge NSERC 315051 and 6793, respectively. M.B. and C.J.B. acknowledge NIH RO1-AI109134. C.J.B. acknowledges NIH AI016137 and AI111201. B.R. acknowledges NHGRI 4U41HG002371. P.C.H., M.A.G. and E.A.P. acknowledge NSERC 418540. O.L.B. and Ch.C. acknowledge ANR-12-EMMA-0007-01. S.F.C. acknowledges Australian Research Council FT110100990.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions C.M.A., E.S.L., M.K., N.R. conceived the study, scientific objectives. C.M.A. led the project and manuscript preparation with input from steering committee members M.K., C.S.J., G.O., P.M., L.W.H., A.S., E.S.L., assisted by S.E. O.C. provided field collected snails. C.M.A. and E.S.L. cultured snails and provided materials. P.M., L.W.H., S.C., L.F., W.C.W., R.K.W., V.M., C.T. developed the sequencing strategy, managed the project, conducted assembly and evaluation. B.R. performed genome alignments. M.C., D.H., S.E., G.G.-C. and D.L. performed the genebuild, managed metadata, performed genome annotation and data analysis, and facilitated Community Annotation with M.C.M.-T. H.D. A.-G., M.Y., E.V.V., M.K. and J.M.B. performed karyotyping and FISH analysis. J.A.T. and M.B. performed linkage mapping. G.O., J.G.A., Y.C.-A., S.G.G., F.L. F.S.O., F.S.P, I.C.R., and L.L.S.S. performed computational analyses of genomic, proteomic, and transcriptomic data, SNP content, secretome, metabolic pathways and annotation of eukaryote protein kinases (ePKs). S.F.C., L.Y., D.L., M.Z. and D.McM. conducted pheroreception studies. M.T.S., K.K.G., U.N. and K.F.H. conducted bacterial symbiont analysis. S.L., S.-M.Z., E.S.L. and B.C.B. performed virus analyses. M.K., P.F., W.I. and N.R. performed annotation of HSP. T.P.Y., X.-J.W., U.B.-W. and N.D. conducted proteogenomic studies of B. glabrata embryonic (Bge) cells and parasite-reactive snail host proteins and data analysis. R.F., A.E.L. and C.S.J. performed annotation of CYP. J.H. performed annotation of NFkB. K.M.B. and J.P.R. performed annotation of conserved immune factors. C.M.A. and J.J.P. performed annotation of FREPs. M.C. and C.M. performed annotation of complement. D.D. performed annotation of apoptosis. B.G. and C.J.B. performed annotation of REDOX balance. O.L.B., D.D., R.G., Ch.C. and G.M. performed annotation of antibacterial defenses. L.d.S. and A.T.P. performed search for antibacterial defense genes. P.C.H., M.A.G. and E.A.P. performed annotation of unknown novel sequences. K.K.G., I.W.C., U.N., K.F.H., M.T.S., Ce.C., T.Q. and C.G. performed annotation and analysis of epigenetic sequences. E.H.B., L.R. doA., M.de.S.G., R.L.C., and W.de.J.J. performed annotation of miRNA (Brazil), K.K.B., R.P. and K.B.S. performed annotation of miRNA (Canada). M.G. performed annotation of periodicity. S.F.C., B.R., T.W., A.E.L. and S.K. conducted neuropeptide studies and data analysis. A.E.L., R.F., S.K., E.J.R., S.J., D.R., C.S.J. and L.R.N. performed annotation of steroidogenesis. J.M.K., B.R. and S.F.C. performed annotation of ovipostatin. A.B.K. and L.L.M. performed tissue location of transcripts analysis. A.J.W. and S.P.L. performed annotation of phosphatases. T.L.L., K.M.R., M.Mi., and R.C. performed annotation of actins and annotation of cardiac transcriptional program with D.L.T. D.J.J., B.K. and M.Me. performed annotation of biomineralization genes. J.C., A.K. and C.F. performed annotation of DNA transposons, global analysis of transposable element landscape, and horizontal transfer events. A.S and C.B. performed repeat/TE analysis. E.S.L., S.M.Z., G.M.M. and S.K.B. conducted comparative B. pfeifferi transcriptome studies and data analysis. C.M.A., did most of the writing with P.M., M.L.M. and contributions from all authors.

08/23/2017

The original version of this Article contained an error in the spelling of the author Leon Di Stefano, which was incorrectly given as Leon di Stephano. This has now been corrected in both the PDF and HTML versions of the Article.

References

- Paraense W. L. The schistosome vectors in the Americas. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 96, (Suppl): 7–16 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King C. H. Parasites and poverty: The case of schistosomiasis. Acta Trop. 113, 95–104 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doenhoff M. J. et al. Praziquantel: Its use in control of schistosomiasis in sub-Saharan Africa and current research needs. Parasitology 136, 1825–1835 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melman S. D. et al. Reduced susceptibility to praziquantel among naturally occurring Kenyan isolates of Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3, e504–e504 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollinson D. et al. Time to set the agenda for schistosomiasis elimination. Acta Trop. 128, 423–440 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Accelerating Work to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases: a Roadmap for Implementation. Available at http://www.who.int/entity/neglected_diseases/NTD_RoadMap_2012_Fullversion.pdf (WHO, 2012).

- Gregory T. R. Genome size estimates for two important freshwater molluscs, the zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) and the schistosomiasis vector snail (Biomphalaria glabrata). Genome 46, 841–844 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adema C. M. et al. A bacterial artificial chromosome library for Biomphalaria glabrata, intermediate snail host of Schistosoma mansoni. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 101, 167–177 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt C. & Yandell M. MAKER2: An annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics 12, 491 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M., Goto S., Sato Y., Furumichi M. & Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D109–D114 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S. F. & Degnan B. Sensory sea slugs: Towards decoding the molecular toolkit required for a mollusc to smell. Commun. Integr. Biol. 3, 423–426 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S. F. et al. Aplysia temptin - the 'glue' in the water-borne attractin pheromone complex. FEBS J. 274, 5425–5437 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel L. A., Bayne C. J. & Loker E. S. The symbiont Capsaspora owczarzaki, nov. gen. nov. sp., isolated from three strains of the pulmonate snail Biomphalaria glabrata is related to members of the Mesomycetozoea. Int. J. Parasitol. 32, 1183–1191 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odoemelam E., Raghavan N., Miller A., Bridger J. M. & Knight M. Revised karyotyping and gene mapping of the Biomphalaria glabrata embryonic (Bge) cell line. Int. J. Parasitol. 39, 675–681 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyereisen R. Arthropod CYPomes illustrate the tempo and mode in P450 evolution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1814, 19–28 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway C. A. & Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 20, 197–216 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley K. M. & Rast J. P. Diversity of animal immune receptors and the origins of recognition complexity in the deuterostomes. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 49, 179–189 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.-M., Adema C. M., Kepler T. B. & Loker E. S. Diversification of Ig superfamily genes in an invertebrate. Science 305, 251–254 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dheilly N. M. et al. A family of variable immunoglobulin and lectin domain containing molecules in the snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 48, 234–243 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falschlehner C. & Boutros M. Innate immunity: Regulation of caspases by IAP-dependent ubiquitylation. EMBO J. 31, 2750–2752 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele P. & Bertrand M. J. M. The role of the IAP E3 ubiquitin ligases in regulating pattern-recognition receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 12, 833–844 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitta G., Vandenbulcke F. & Roch P. Original involvement of antimicrobial peptides in mussel innate immunity. FEBS Lett. 486, 185–190 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahoor Z., Davies A. J., Kirk R. S., Rollinson D. & Walker A. J. Nitric oxide production by Biomphalaria glabrata haemocytes: effects of Schistosoma mansoni ESPs and regulation through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Parasit. Vectors 2, 18–18 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fneich S. et al. 5-methyl-cytosine and 5-hydroxy-methyl-cytosine in the genome of Biomphalaria glabrata, a snail intermediate host of Schistosoma mansoni. Parasit. Vectors 6, 167–167 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer K. K. et al. Cytosine methylation regulates oviposition in the pathogenic blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. Nat. Commun. 2, 424–424 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M. et al. Polyethyleneimine (PEI) mediated siRNA gene silencing in the Schistosoma mansoni snail host, Biomphalaria glabrata. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5, e1212 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer K. K. et al. The Biomphalaria glabrata DNA methylation machinery displays spatial tissue expression, is differentially active in distinct snail populations and is modulated by interactions with Schistosoma mansoni. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rotenberg L. et al. Oviposition rhythms in Biomphalaria spp. (Mollusca: Gastropoda). 1. Studies in B. glabrata, B. straminea and B. tenagophila under outdoor conditions. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 341B, 763–771 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koene J. M. et al. Male accessory gland protein reduces egg laying in a simultaneous hermaphrodite. PLoS ONE 5, e10117–e10117 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakadera Y. et al. Receipt of seminal fluid proteins causes reduction of male investment in a simultaneous hermaphrodite. Curr. Biol. 24, 859–862 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berriman M. et al. The genome of the blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni. Nature 460, 352–358 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simakov O. et al. Insights into bilaterian evolution from three spiralian genomes. Nature 493, 526–531 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G. et al. The oyster genome reveals stress adaptation and complexity of shell formation. Nature 490, 49–54 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai I. J. et al. The genomes of four tapeworm species reveal adaptations to parasitism. Nature 496, 57–63 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertin C. B. et al. The octopus genome and the evolution of cephalopod neural and morphological novelties. Nature 524, 220–224 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripps R. M. & Olson E. N. Control of cardiac development by an evolutionarily conserved transcriptional network. Dev. Biol. 246, 14–28 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medioni C. et al. The fabulous destiny of the Drosophila heart. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19, 518–525 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland N. D., Venkatesh T. V., Holland L. Z., Jacobs D. K. & Bodmer R. AmphiNk2-tin, an amphioxus homeobox gene expressed in myocardial progenitors: Insights into evolution of the vertebrate heart. Dev. Biol. 255, 128–137 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg E. A., Mahaffey J. W., Bond B. J. & Davidson N. Transcripts of the six Drosophila actin genes accumulate in a stage- and tissue-specific manner. Cell 33, 115–123 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlini D. B., Reece K. S. & Graves J. E. Actin gene family evolution and the phylogeny of coleoid cephalopods (Mollusca: Cephalopoda). Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 1353–1370 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin F. Y. T., Bryant M. J. & Johnstone A. Molecular evolution and phylogeny of actin genes in Haliotis species (Mollusca: Gastropoda). Zool. Study 46, 734–745 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Mounier N., Gouy M., Mouchiroud D. & Prudhomme J. C. Insect muscle actins differ distinctly from invertebrate and vertebrate cytoplasmic actins. J. Mol. Evol. 34, 406–415 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DesGroseillers L., Auclair D., Wickham L. & Maalouf M. A novel actin cDNA is expressed in the neurons of Aplysia californica. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1217, 322–324 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyrberg E. A., Bond B. J., Hershey N. D., Mixter K. S. & Davidson N. The actin genes of Drosophila: Protein coding regions are highly conserved but intron positions are not. Cell 24, 107–116 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchin Y. & Moroz L. L. Molluscan mobile elements similar to the vertebrate Recombination-Activating Genes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 369, 818–823 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan N. et al. Nimbus (BgI): An active non-LTR retrotransposon of the Schistosoma mansoni snail host Biomphalaria glabrata. Int. J. Parasitol. 37, 1307–1318 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace J. K., Gilbert C., Clark M. S. & Feschotte C. Repeated horizontal transfer of a DNA transposon in mammals and other tetrapods. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 17023–17028 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong R. J. et al. Evolutionary relationships and biogeography of Biomphalaria (Gastropoda: Planorbidae) with implications regarding its role as host of the human bloodfluke, Schistosoma mansoni. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 2225–2239 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell G. et al. Molecular evidence supports an African affinity of the Neotropical freshwater gastropod, Biomphalaria glabrata, Say 1818, an intermediate host for Schistosoma mansoni. Proc. Biol. Sci. 267, 2351–2358 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adema C. M. et al. Will all scientists working on snails and the diseases they transmit please stand up? PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1835 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M. et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437, 376–380 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 20, 265–272 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao G. et al. Graph accordance of next-generation sequence assemblies. Bioinformatics. 28, 13–16 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo-Calderón G. I. et al. VectorBase: an updated bioinformatics resource for invertebrate vectors and other organisms related with human diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D707–D713 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra G., Bradnam K. & Korf I. CEGMA: A pipeline to accurately annotate core genes in eukaryotic genomes. Bioinformatics. 23, 1061–1067 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E. et al. Web Apollo: A web-based genomic annotation editing platform. Genome Biol. 14, R93–R93 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offord V. & Werling D. LRRfinder2.0: A webserver for the prediction of leucine-rich repeats. Innate Immun. 19, 398–402 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References

Sequence data sets

Biomphalaria glabrata linkage groups

Proteome InterProscan annotation

proteome KEGG/SNV mapping

Prediction of secreted proteins

fasta sequences of predicted secreted proteins (fasta)

secretome B. glabrata, Interproscan annotation

Pfam domain annotation of predicted secretome

Transcripts, tissue distribution

Secreted_proteins SCW&ES_Topblast_results

Predicted GPCR genes of Biomphalaria glabrata

Mycoplasma/Mollicute annotation

HSP annotation

GREPs bind to S.mansoni

HSP expression in Bge cell-line

Cytochrome P 450 (CYP) genes of B. glabrata.

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and cytokines

TLR pathway signaling

Complement-like factors.

Apoptosome

REDOX genes

Antimicrobial factors

Antimicrobial factors expression profiles

Annotation unknown microarray features

Expression patterns of previous unknowns.

Epigenetic toolbox genes

miRNA and piRNA pathway factors

Conserved precursor miRNAs, Structural, location and thermodynamic

Conserved mature miRNAs B. glabrata and homologs

conserved precursor miRNAs tissue distribution in B. glabrata

Conserved miRNA target gene predictions

Novel miRNAs predictions

Novel predicted miRNA and target genes

Neuropeptides precursors and prepropeptides

neuropeptides, tissue distribution

Predicted bioactive cleavage products of neuropeptides

Steroidogenesis pathway genes

Cardiac regulatory and structural genes in B. glabrata

Biomphalaria glabrata actins

Biomineralization transcripts from B. glabrata mantle tissue.

Low-copy transposable elements (TE) abundance

Identity of 34 B. pfeifferi and B. glabrata sequence homologs

Sequence Identity of B. pfeifferi homologs to 162 B. glabrata genes from

Data Availability Statement

The sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in GenBank with the accession codes SRX005826, -27, -28; SRX008161, -2; SRX648260, -61, -62, -63, -64, -65, -66, -67, -68, -69, -70, -71; SRA480937; SRA480939; SRA480940; SRA480945; TI accessions2091872204-2092480271; 2104228958-2104243968; 2110153721-2118515136; 2181062043-2181066224; 2193113537-2193116528; 2204642410-2204763511; 2204820860-2204852286; 2213009530-2213057324; 2260448774-2260450167. Also see Supplementary Data 1. The assembly and related data are available from VectorBase, https://www.vectorbase.org/organisms/biomphalaria-glabrata. The Biomphalaria glabrata genome project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession number APKA00000000.1