Abstract

Background

Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-based tissue engineering has focused on inducing new bone efficiently. However, modeling and remodeling of BMP-induced bone have rarely been discussed. Teriparatide (parathyroid hormone [PTH] 1-34) administration initially increases markers of bone formation, followed by an increase in bone resorption markers. This unique activity would be expected to accelerate the modeling and remodeling of new BMP-induced bone.

Methods

Male Sprague-Dawley rats underwent posterolateral spinal fusion surgery and implantation of collagen sponge containing either 50 μg recombinant human (rh)BMP-2 or saline. PTH 1-34 (60 μg/kg, 3 times/week) or saline injections were continued from preoperative week 2 week to postoperative week 12. The volume and quality of newly formed bone were monitored by in vivo micro-computed tomography and analyses of bone histomorphometry and serum bone metabolism markers were conducted at postoperative week 12.

Results

Microstructural indices of the newly formed bone were significantly improved by PTH 1-34 administration, which significantly decreased the tissue volumes of the fusion mass at postoperative week 12 compared to that at postoperative week 2. Bone histomorphometry and serum analyses showed that PTH administration significantly increased both bone formation and resorption markers. Analysis of the histomorphometry of cortical bone identified predominant periosteal bone resorption and endosteal bone formation.

Conclusions

Long-term intermittent administration of PTH 1-34 significantly accelerated the modeling and remodeling of new BMP-induced bone.

Clinical relevance

Our results suggest that the combined administration of rhBMP-2 and PTH 1-34 facilitates qualitative and quantitative improvements in bone regeneration, by accelerating bone modeling and remodeling.

Keywords: Bone morphogenetic protein, Bone remodeling, Bone modeling, PTH 1-34, Bone regeneration

Highlights

-

•

The present study found that intermittent administration of PTH 1-34 significantly decreased the TV of new rhBMP-2-induced bone, following the initial formation of a fusion mass equivalent to that of the control group.

-

•

Bone histomorphometry demonstrated predominant bone resorption at the periosteum and bone formation at the endosteum in rats receiving PTH 1-34.

-

•

These results indicated that PTH 1-34 supported modeling of rhBMP-2-induced bone in addition to the remodeling effect which confirmed by bone histomorphometry and serum markers.

1. Introduction

Bone grafting is commonly used to treat skeletal disorders involving bone defects or spinal instability (Steinmann and Herkowitz, 1992). Failure of bony fusion results in pseudarthrosis, pain, and disability (Arrington et al., 1996, Robertson and Wray, 2001, Steinmann and Herkowitz, 1992). Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) may provide an alternative to bone grafting and is the leading osteoinductive growth factor used clinically in bone-related regenerative medicine today (Boden et al., 2000, Boden et al., 2002, Urist, 1965, Wozney et al., 1988).

Although this therapy is effective, use of high BMP doses can cause complications including inflammatory responses and unintended bone formation; these restrict its widespread application (Shields et al., 2006, Smucker et al., 2006). Improved BMP delivery systems have the potential to produce efficient and spatially controlled bone formation (Kaito et al., 2005). However, modeling and remodeling of BMP-induced bone, processes that occur during normal late-phase fracture healing, have not been investigated thoroughly.

Teriparatide (parathyroid hormone [PTH] 1-34) is the only anabolic agent that has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of osteoporosis. This hormone has a unique mechanism of action; continuous administration of PTH 1-34 shows a catabolic effect, while intermittent administration demonstrates an anabolic effect (Canalis, 2010;Canalis et al., 2007, Dempster et al., 1993, Jilka, 2007, Tam et al., 1982). Recent studies demonstrated that intermittent PTH 1-34 administration promoted fracture healing (Aspenberg et al., 2010, Gallacher and Dixon, 2010, Komatsubara et al., 2005, Manabe et al., 2007, Neer et al., 2001). Another study found that intermittent PTH 1-34 administration significantly increased fusion rates and newly formed bone quality, concluding that combined administration of rhBMP-2 and PTH 1-34 had a synergistic effect in a rat model of rhBMP-2-induced spinal fusion. Interestingly, at postoperative week 6, the newly formed bone tissue volume (TV) in rats treated with rhBMP-2 tended to be lower than in animals treated with PTH 1-34 (Morimoto et al., 2014). These findings suggest the possibility that PTH 1-34 influences modeling and remodeling of newly formed bone. However, it is unclear whether the newly formed bone TV was low from the outset or decreased over time in these rats. The purpose of this study was to elucidate the time course of change in TV induced by the administration of PTH1-34 by determining the dimension of the newly formed bone (TV) using serial in vivo micro-computed tomography (CT) and to quantify bone formation and resorption at periosteum and endosteum of the newly formed bone by bone histomorhometry.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Animal treatments

A total of 37 male, 8-week-old, Sprague-Dawley rats with an initial average body weight of 305.9 g (range, 280–330 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc. (Yokohama, Japan) and used in the present study. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Regulations on Animal Experimentation at Osaka University. The study groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Treatment groups.

| Implanted material | Injected material | |

|---|---|---|

| Group A (n = 9) | Collagen carrier | Saline |

| Group B (n = 9) | PTH1-34 | |

| Group C (n = 10) | Collagen carrier + 50 μg rhBMP-2 | Saline |

| Group D (n = 9) | PTH1-34 |

2.1.1. Administration of PTH 1-34

Rats were treated with subcutaneous injections of either PTH 1-34 (60 μg/kg) 3 times a week (180 μg/kg/week) or 0.9% saline vehicle. Injections commenced 2 weeks prior to surgery, in order to enhance the anabolic effect of PTH 1-34 at the time of surgery, and continued until the animals were euthanized. Animals were weighed every 7–10 days, and injection volumes were adjusted accordingly.

2.1.2. Surgery

Rats were anesthetized with a combination of 0.15 mg/kg of medetomidine (Domitol; Nippon Zenyaku Kogyo Co., Ltd., Fukushima, Japan), 2 mg/kg of midazolam (Dormicum; Astellas Pharma Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and 2.5 mg/kg of butorphanol (Vetorphale; Meiji Seika, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). In addition, preoperative antibiotic (20,000 U/kg penicillin G; Meiji Seika) was administered subcutaneously. We then surgically induced posterolateral lumbar fusion (Kaito et al., 2013, Morimoto et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2003). A posterior midline skin incision was made, followed by 2 separate paramedian incisions in the lumbar fascia 3 mm from the midline, through which the transverse processes were exposed. The L4 and L5 transverse processes were decorticated using a high-speed burr.

A commercially available absorbable collagen sponge (CollaCote; Zimmer Dental Inc., CA, USA) was cut into 5 × 10 mm fragments and placed in a sterile tube. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or rhBMP-2 (50 μg in PBS) was applied to the sponge just before implantation on each side of the spine. We chose 50 μg rhBMP-2 because this corresponded to a high clinical dose (1500 μg/mL) (Morimoto et al., 2014). The fascia and skin incisions were closed using a 4-0 absorbable suture. The rats were housed in separate cages and allowed to eat and drink ad libitum while their condition was monitored daily.

2.1.3. Calcein double labeling for bone histomorphometry

All rats were injected subcutaneously with 10 mg/kg calcein (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) at 5 and 2 days before they were euthanized.

2.1.4. Euthanasia and tissue collection

Immediately prior to euthanizing the rats by anesthetic overdose 12 weeks after surgery, blood samples were collected for analysis of bone metabolism markers and stored at − 80 °C. Spinal segments and femurs were harvested and fixed with 10% formalin or 70% ethanol for further assessments.

2.2. Serial bone TV measurement by in vivo micro-CT

The TV of the L4-L5 fusion segments (from the bottom of the L5 transverse process cranially to the top of L4 end plate) was measured in vivo at a resolution of 59 μm at time 0 (just before surgery) and at 2, 6, 8, and 12 weeks after surgery.

2.3. Assessment of L4-L5 fusion

L4-L5 fusion was assessed using the two methods described below. Each was performed in a blinded manner by three independent observers and unanimous agreement was required before these were considered to be fused.

2.3.1. Micro-CT

The spines were scanned using high-resolution micro-CT (R_mCT; Rigaku Mechatronics, Tokyo, Japan) at 90 kV and 200 μA. Visualization and data reconstruction were performed using the TRI/3D-BON (RATOC System Engineering, Tokyo, Japan). Coronal and sagittal L4-L5 images at a resolution of 40 μm/voxel were evaluated for clear evidence of bridging bone formation with cortical continuity between the L4 and L5 transverse processes.

2.3.2. Manual assessment

The explanted lumbar spines were manually tested for intersegmental motion. Any motion detected in the anterior-posterior and left-right direction was considered to indicate a failure of fusion, while the absence of motion was considered to indicate successful fusion.

2.4. Microstructural analysis

The quality of the newly formed fusion mass between the transverse processes was analyzed as described previously (Morimoto et al., 2014). Fusion mass scanning was initiated from the lower endplate level of the L4 vertebral body and continued cranially at 2.0-mm increments (fifty slices) at a resolution of 40 μm/voxel on each side. The bone volume (BV)/TV, trabecular thickness (Tb·Th), trabecular number (Tb·N), trabecular separation (Tb·Sp), thickness of cortical bone (Ct), and cortical bone ratio (Cv/Av) were determined.

2.5. Analysis of the systemic effects of PTH 1-34

The BV/TV ratios of the distal femoral epiphysis and L6 vertebral body were analyzed at 40 μm/voxel. Scanning of the distal femur was initiated at 1.5 mm proximal to the growth plate and continued at 3.0-mm increments (75 slices) in order to exclude the primary spongiosa of the femur. Scanning of the L6 vertebral body was initiated at 1.0 mm cranial to the lower growth plate and continued at 3.2-mm increments (80 slices) in order to exclude the primary spongiosa of the vertebrae.

2.6. Analysis of serum markers of bone metabolism

Serum bone metabolism markers were analyzed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays specific for N-terminal propeptide of type 1 procollagen (P1NP; Rat/Mouse P1NP EIA), type 1 collagen cross-linked C-telopeptides (CTX-1; RatLaps ELISA), and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-5b (TRACP-5b; RatTRAP Assay) (all from Immunodiagnostic Systems Limited, Fountain Hills, AZ, USA), and osteocalcin (Rat Osteocalcin EIA Kit; Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan), according to the manufacturers' instructions. Serum from all animals was measured once for each marker.

2.7. Histologic analysis

Five samples each from group C and group D were prepared for undecalcified bone histomorphometry analysis; the remaining samples were prepared for decalcified histological analysis. The dissected and formalin-fixed spines were demineralized with 50% formic acid and 10% sodium citrate, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and embedded in paraffin wax. Serial 5-μm coronal sections of the operated segments were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

2.7.1. Bone histomorphometry

Histomorphometric parameters were analyzed using undecalcified sections of fusion mass in cortical and cancellous bone. Only samples from groups C and D were used for the analysis because of the lack of new bone formation in groups A and B. The dissected lumbar spines were fixed with 70% ethanol, stained with Villanueva bone stain, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and embedded in methyl methacrylate. Static and dynamic bone histomorphometrical measurements of the newly formed bone were performed using a semiautomatic image-analyzing system (System Supply, Nagano, Japan) and a fluorescent microscope at × 320 magnifications. The bone histomorphometric parameters measured were: osteoid and eroded surface/unit bone surface (OS/BS and ES/BS), double-labeled and single-labeled surface/unit BS (dLS/BS and sLS/BS), number of osteoblasts and osteoclasts/unit BS (N·Ob/BS and N·Oc/BS), mineralizing surfaces/unit BS (MS/BS), mineral apposition rate (MAR), and bone formation rate/unit BS (BFR/BS) and bone resorption rate (BRsR) 25.

2.8. Statistical analyses

PASW software (version 18; SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for all of the analyses. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare variables and the level of significance was p < 0.05.

3. Results

One rat in group C died just after surgery and another rat in this group died 2 weeks after surgery, following anesthesia for micro-CT; thus, 35 rats were included in the final analysis.

3.1. Fusion analysis

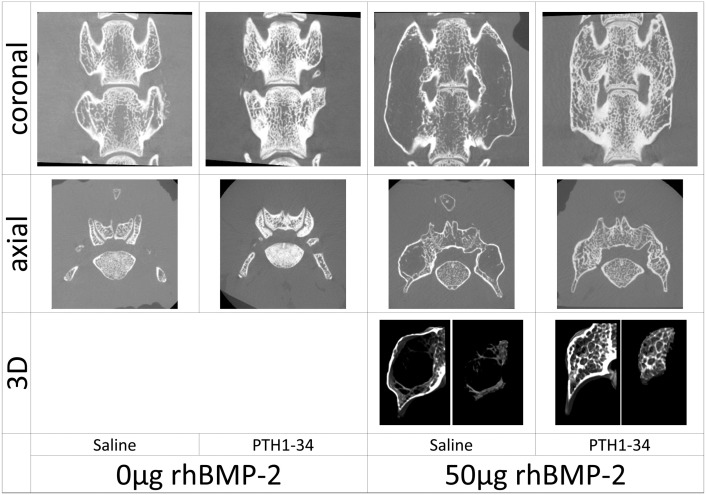

All fusion assessments (micro-CT and manual) confirmed L4-L5 osseous fusion in 100% of the rats exposed to rhBMP-2 (groups C and D), whereas no osseous fusion was found in non-exposed groups A or B (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The images shown of coronal and axial sections of rats in the indicated treatments groups were generated using micro-CT at postoperative 12 weeks. No osseous fusion was found in the non-recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2)-treated rats were observed irrespective of the administration of parathyroid hormone 1-34. In the rhBMP-2 treated rats without PTH 1-34 administration, the induced fusion mass was composed with an eggshell like cortical bone and contained scarce trabecular bone inside. The rhBMP-2-treated rats with PTH 1-34 administration demonstrated a small fusion mass that was completely filled with thick trabecular bone.

3.2. Serial bone TV measurement by in vivo micro-CT

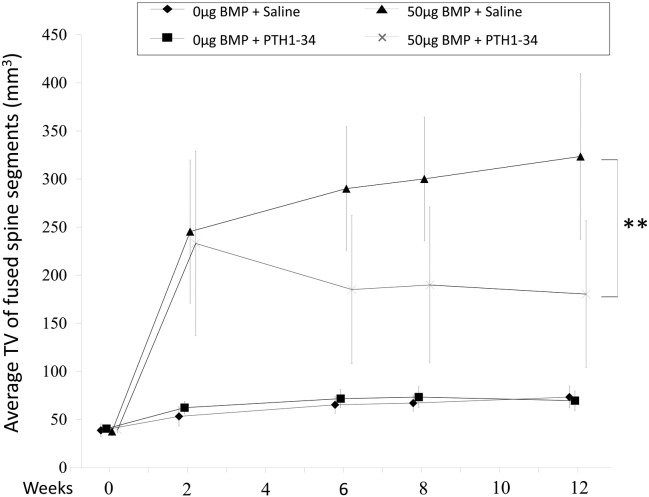

The study group TVs showed no significant differences on day 0. The TVs of groups C and D markedly increased to a similar extent 2 weeks after surgery (245.4 ± 74.5 mm3 and 233.1 ± 95.9 mm3, respectively). However, subsequent TVs in rats exposed to rhBMP-2 differed dramatically in the presence or absence of PTH 1-34. The group D TV decreased over time until 12 weeks, while the group C TV continued to increase over this time-period. This resulted in a significant lower TV in the PTH 1-34-treated group D at 12 weeks (180.4 ± 76.5 mm3), than in the control group C (323.5 ± 86.3 mm3) (p < 0.01; Fig. 2). Groups A and B showed a slight increase in TV 12 weeks after surgery, which may reflect age-related skeletal growth (group A: 73.3 ± 11.3 mm3; group B: 69.5 ± 10.2 mm3; p = 0.79).

Fig. 2.

Serial tissue volume (TV) measurements of newly formed bone by in vivo micro-computed tomography are shown over the 12-week study in the indicated treatment groups. rhBMP-2, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein; PTH 1-34 parathyroid hormone 1-34. **p < 0.01. TV is defined as a total bone tissue volume.

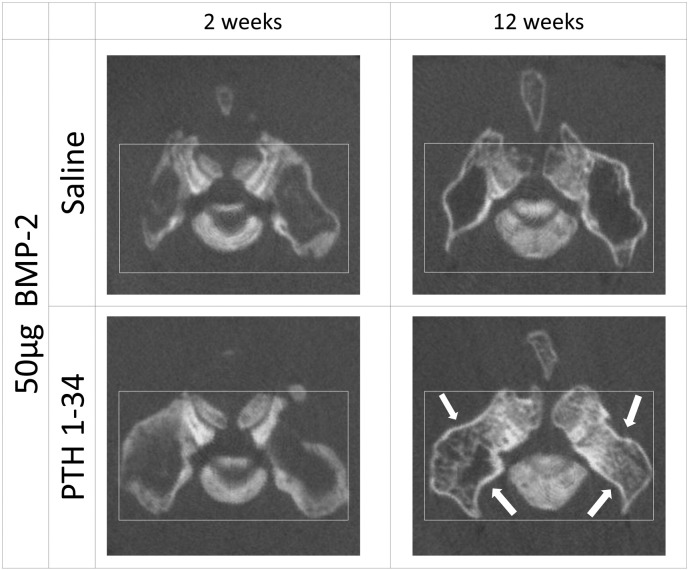

The axial reconstructed images of rats exposed to rhBMP-2 clearly demonstrated that in the saline-treated group C, the contour of the fusion mass gradually enlarged between 2 and 12 weeks postoperatively, with little bone formation inside this mass. In contrast, the contour of the fusion mass apparently shrank between postoperative weeks 2 and 12 weeks in the PTH 1-34-treated group D, with robust new bone formation inside this mass (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Representative axial micro computed tomography images at postoperative weeks 2 and 12 are shown for the indicated study groups. rhBMP-2, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein; PTH 1-34 parathyroid hormone 1-34. Arrows indicate shrinkage of the fusion mass in the groups treated with PTH 1-34.

3.3. Microstructural indices of the newly formed bone

Groups C and D were used for this analysis because specimens from rats that were not exposed to rhBMP-2 (groups A and B) showed little or no new bone formation. PTH 1-34 administration significantly increased the trabecular BV, BV/TV, Tb.Th, and Tb.N, while the Tb.Sp significantly decreased. The cortical bone ratio (Sv/AV [%]) and average thickness (Ct [μm]) were also increased by PTH 1-34 administration, while the TV of the newly formed bone was significantly decreased (Table 2).

Table 2.

Microstructural indices of newly formed bone.

| Parameter | Injected material |

|

|---|---|---|

| Saline | PTH 1-34 | |

| Tissue volume (TV, mm3) | 19.0 ± 5.6 | 12.6 ± 8.3a |

| Bone volume (BV,mm3) | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 1.8⁎ |

| Bone volume density (BV/TV, %) | 3.8 ± 2.1 | 16.7 ± 7.2⁎⁎⁎ |

| Trabecular thickness (Tb.Th, μm) | 162.4 ± 17.2 | 200.0 ± 41.0⁎⁎ |

| Trabecular number (Tb.N, mm− 1) | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 0.52 ± 0.25⁎⁎ |

| Trabecular separation (Tb.Sp, μm) | 877.2 ± 301.8 | 364.2 ± 161.4⁎⁎ |

| Cortical bone ratio (Cv/Av, %) | 37.2 ± 5.4 | 56.4 ± 18.4⁎⁎ |

| Cortical bone thickness (Ct, μm) | 360.5 ± 37.7 | 539.2 ± 193.7⁎⁎ |

Values are given as the mean and the standard deviation. The values were significantly higher in the group that received PTH 1-34.

The value was significantly lower in the group that received PTH 1-34.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

3.4. Effect of PTH administration on the adjacent vertebra (L6) and femur

The BV/TV values of both the distal femoral epiphysis and the L6 vertebral body were significantly increased by the administration of PTH 1-34, as compared to those observed in control rats (femur: 28.4 ± 10.7% vs. 61.4 ± 13.5%, p < 0.0001; L6 vertebra: 22.8 ± 10.6% vs. 44.0 ± 10.8%, p < 0.00001, respectively).

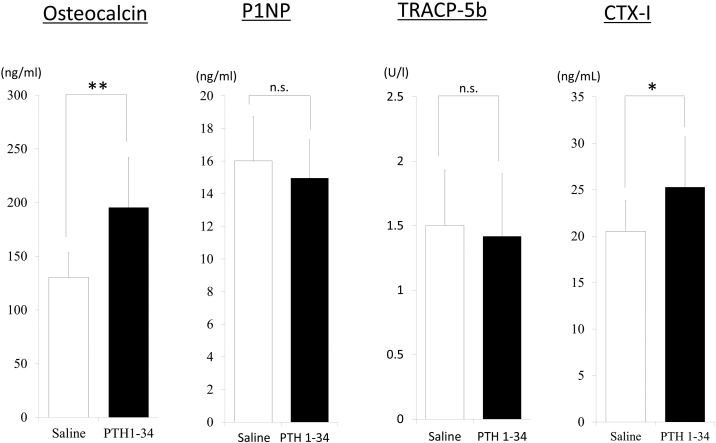

3.5. Serum bone metabolism markers

Significantly higher levels of osteocalcin (p < 0.001) and CTX-1 (p < 0.01) were observed in rats treated with PTH 1-34, as compared to the levels in rats treated with saline, whereas these groups showed no differences in the serum levels of P1NP or TRACP-5b (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Osteocalcin (bone formation marker) and type 1 collagen cross-linked C-telopeptides (CTX-1; bone resorption marker) significantly increased with the administration of teriparatide, but tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRACP)-5b and N-terminal propeptide of type 1 procollagen (P1NP) levels were not significantly altered (n.s.). The double asterisk indicates p < 0.0001, the single asterisk indicates p < 0.01.

3.6. Histology

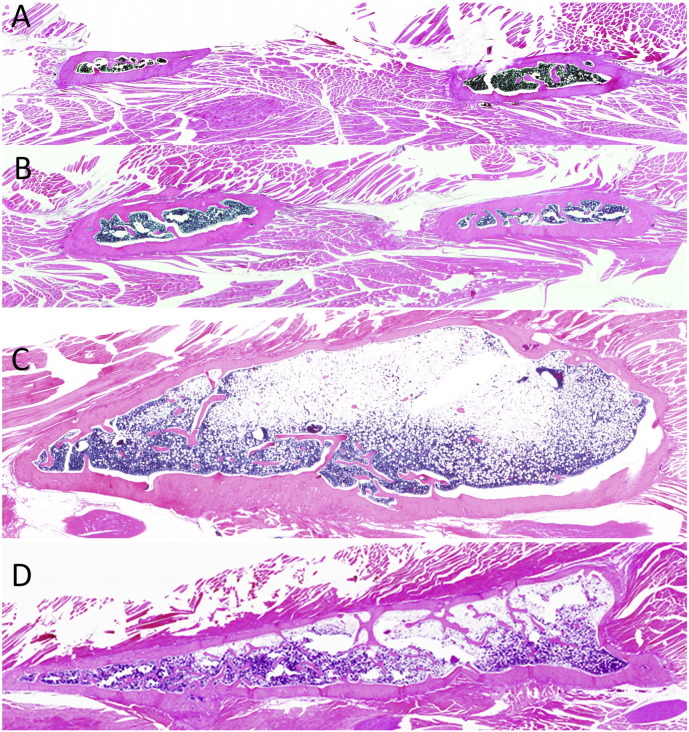

Microscopic evaluation of the coronal spinal sections showed that groups A and B showed minimal new bone formation, irrespective of PTH 1-34 administration (Fig. 5A and B), whereas those treated with rhBMP-2 (groups C and D) showed abundant new bone formation, bridging the transverse processes. The majority of the newly formed fusion mass in group C, which did not receive PTH 1-34, comprised fatty marrow within a large thin eggshell-like cortical bone (Fig. 5C). However, group D had a relatively small fusion mass that was filled with abundant trabecular bone (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Lower-power photomicrographs of coronal sections of the L4-5 transverse spine processes are shown for rats in the indicated study groups (A–D) at a magnification of × 0.5. See Table 1 for a description of the study group treatments.

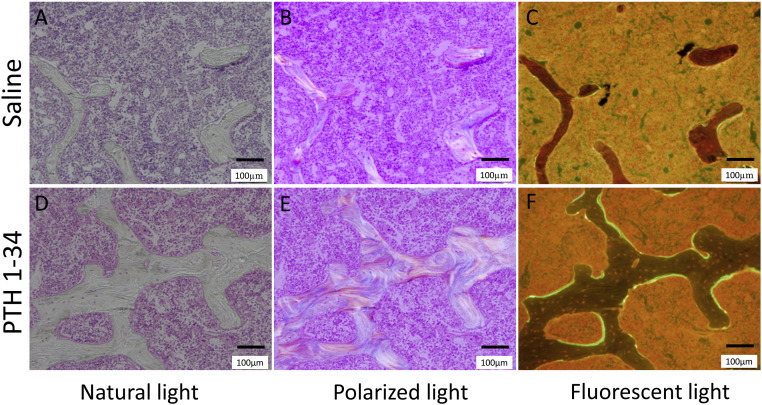

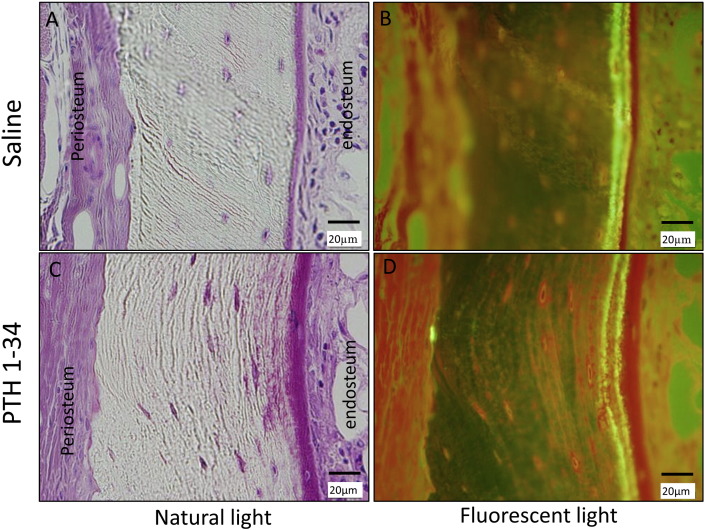

3.7. Bone histomorphometry

The administration of PTH 1-34 significantly increased the MAR, dLs/BS, MS/BS, and N·Oc/BS of cancellous bone. This indicated that PTH 1-34 stimulated modeling and remodeling processes within 12 weeks of surgery (Table 3). Cortical bone histomorphometry demonstrated that PTH 1-34 administration significantly increased the bone resorption rate at the periosteum and MAR at the endosteum. This treatment also tended to increase endosteum BFR/BS and sLs/BS, although this failed to achieve statistical significance (p = 0.08). These findings revealed predominant periosteal bone resorption and endosteal bone formation in PTH 1-34-treated rats (Fig. 6, Fig. 7).

Table 3.

Bone histomorphometric parameters of fusion mass.

| Parameters | Saline | PTH 1-34 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancellous bone | OS/BS (%) | 8.7 ± 5.0 | 13.2 ± 4.8 | |

| ES/BS (%) | 13.7 ± 4.7 | 13.4 ± 4.0 | ||

| N·Ob/BS (N/mm) | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 7.2 ± 2.9 | ||

| N·Oc/BS (N/mm) | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.5⁎ | ||

| MS/BS (%) | 10.9 ± 6.3 | 22.1 ± 6.0⁎ | ||

| MAR (μm/day) | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.2⁎ | ||

| BFR/BS (mm3/mm2per y) | 0.05 ± 0.05 | 0.15 ± 0.05⁎ | ||

| BRs.R (mm3/mm2per y) | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | ||

| Cortical bone | periosteum | BFR/BS (mm3/mm2per y) | 0.09 ± 0.14 | 0.34 ± 0.22 |

| BRs.R (mm3/mm2per y) | 0.13 ± 0.14 | 2.04 ± 3.45⁎ | ||

| dLs/BS (%) | 11.1 ± 14.6 | 40.8 ± 25.9 | ||

| sLs/BS (%) | 9.6 ± 6.0 | 9.6 ± 6.0 | ||

| MAR (μm/day) | 5.6 ± 4.1 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | ||

| endosteum | BFR/BS (mm3/mm2per y) | 0.22 ± 0.11 | 0.42 ± 0.20 | |

| BRs.R (mm3/mm2per y) | 0.33 ± 0.33 | 1.01 ± 1.30 | ||

| dLs/BS (%) | 36.5 ± 7.6 | 47.0 ± 19.4 | ||

| sLs/BS (%) | 23.0 ± 15.8 | 11.1 ± 2.9 | ||

| MAR (μm/day) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.5⁎ | ||

Values are given as the mean and standard deviation. BFR/BS, bone formation rate, BRs.R, bone resorption rate; dLs/BS, double-labeled surface; ES/BS, eroded surface; N.Ob/BS, MAR, mineral apposition rate; MS/BS, mineralizing surface; osteoblast number; N.Oc/BS, osteoclast number; OS/BS, osteoid surface; sLs/BS, single-labeled surface; PTH: parathyroid hormone.

The value was significantly higher in the group that received PTH 1-34 (p < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Bone morphohistometorical features of cancellous bone in the fusion mass of the recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2)-treated rats (coronal sections), in the presence or absence of parathyroid hormone 1-34 (PTH 1-34) treatment, as indicated.

Fig. 7.

Bone morphohistometorical features of cortical bone in fusion mass of the recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (rhBMP-2)-treated rats (coronal sections), in the presence or absence of parathyroid hormone 1-34 (PTH 1-34) treatment, as indicated.

4. Discussion

The present study showed that intermittent administration of PTH 1-34 significantly decreased the TV of new rhBMP-2-induced bone, following the initial formation of a fusion mass equivalent to that of the control group. Bone histomorphometry demonstrated predominant bone resorption at the periosteum and bone formation at the endosteum in rats receiving PTH 1-34. These results indicated that PTH 1-34 supported modeling of rhBMP-2-induced bone. Furthermore, the increased bone formation and bone resorption identified by bone histomorphometry and serum markers indicated that PTH 1-34 had a remodeling effect on rhBMP-2-induced bone; to definitely distinguish between modeling and remodeling, the systemic parameters of bone turnover were measured.

We believe that the decrease in the TV of the newly formed bone by PTH1-34 administration is interesting because the effects are applicable to the modeling process in fracture healing. The modeling effect by PTH1-34 enables spatial control of the excessively formed BMP-2-induced new bone possibly in response to the mechanical stress. The following three mechanisms may contribute to this accelerated bone modeling and remodeling. First, the combined administration of rhBMP-2 and PTH 1-34 produces a synergistic induction and differentiation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts in the rhBMP-2-induced fusion mass. Previous findings suggest that four processes may underlie these effects. (1) PTH 1-34 stimulates T-cell production of the osteogenic Wnt ligand, Wnt10b, which stimulates bone formation by osteoblasts (Baron and Kneissel, 2013). (2) BMP signaling upregulates the expression of SOST, leading to the increased translation of sclerostin, which negatively regulates the Wnt pathway (Kamiya et al., 2008). PTH 1-34 inhibits osteocyte sclerostin expression and activates Wnt signaling (Fermor and Skerry, 1995), which promotes the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells to osteoblasts, rather than adipocytes (Takada et al., 2009). Indeed, we found that the newly formed bone was filled with adipose tissue in rats exposed to rhBMP-2 without PTH 1-34. (3) PTH stimulates the endocytosis of the BMP antagonist, thus enhancing BMP signaling by blocking the negative influence of BMP antagonists, including noggin (Yu et al., 2012). (4) The osteoblasts induced by the above pathways also recruit and differentiate osteoclasts by expressing receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) (Nakashima et al., 2011).

Second, PTH 1-34 has a unique mechanism of action in bone whereby intermittent administration leads to a rapid increase in bone formation markers, followed by an increase in bone resorption markers (Canalis, 2010, Canalis et al., 2007,Jilka, 2007, Manabe et al., 2007, Tam et al., 1982). The present study demonstrated that markers of both bone formation and resorption significantly increased in the PTH 1-34-treated group 12 weeks after surgery. A high bone turnover, with predominant bone formation by osteoblasts, can promote bone modeling and remodeling. The obvious osteon structure visible using polarization microscopy also confirmed the accelerated remodeling in the rhBMP-2-induced bone in rats treated with PTH 1-34 (Fig. 6, E).

Third, recent studies suggest that osteocyte PTH/PTH-related peptide type 1 receptor signaling regulates anabolic and catabolic skeletal responses to PTH (Saini et al., 2013). Osteocytes, the most abundant cells in bone, have recently emerged as important modulators of bone modeling (Maycas et al., 2015, Saini et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2009). During normal physiological skeletal growth, bone modeling involves bone formation at the periosteum and bone resorption at the endosteum. However, in pathological situations, such as angulated long bone malunions in children or fracture healing, diverse patterns of bone architecture modeling occur in response to mechanical stress; these include predominant periosteal bone resorption and endosteal bone formation. PTH has profound effects on cortical bone, stimulating periosteal expansion and accelerating intracortical bone remodeling by activating osteocyte PTH receptors during normal bone modeling (Rhee et al., 2011). Intermittent PTH administration stimulates osteocyte-mediated modeling in response to mechanical stress through connexin 43 and osteocyte-mediated RANKL expression (Pacheco-Costa et al., 2015). These mechanisms might play a role in the modeling and remodeling of rhBMP-2-induced bone by PTH 1-34.

All these data suggest that concomitant administration of PTH 1-34 and rhBMP-2 could promote the production of high-quality bone, and also promote the modeling and remodeling of newly formed bone in response to mechanical requirements (Komatsubara et al., 2005).

This study has several limitations. We employed only one dose of rhBMP-2 (50 μg), although we previously tested 2 μg and 50 μg rhBMP-2. We anticipated that it would be difficult to compare the effects of PTH 1-34 on modeling and remodeling in a 2-μg rhBMP-2 group because the fusion rates were previously around 50% in this group and pseudoarthrosis would affect the micro-CT and bone histomorphometory results. A further limitation is that the current spinal fusion model in quadrupedal rodents cannot be directly extrapolated to spinal arthrodesis in humans because of the differences in biomechanics and biological effects of the agents. Another limitation is the lack of a biomechanical assessment of fusion because of the size and complex geometry of the rat spine. However, in this study, 100% fusion was observed in the rhBMP-2-treated rats and the microstructural indices derived using micro-CT were previously reported to correlate with biomechanical properties (Leahy et al., 2010). Another limitation is the lack of verification of influence of mechanical stress on the PTH1-34 related modeling effect. In this model of spinal fusion, it is difficult to inhibit the effect of mechanical stress by external fixation or other methods. A study using the femoral defect model combined with plate fixation is underway. The results from the study will further clarify the relationship between the modeling effect of PTH1-34 and mechanical stress. In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that intermittent PTH 1-34 administration significantly accelerated the modeling (volume reduction) of rhBMP-2-induced new bone and significantly improved the quality of the newly formed bone by accelerating remodeling. Our results indicate that the combined administration of rhBMP-2 and PTH 1-34 may enable the spatial control of newly formed bone in the presence of mechanical stress.

Author's contribution statement

Takashi Kaito: study design, animal operation, data-analysis, interpretation data; Tokimitsu Morimoto: animal operation, data-analysis; Sadaaki Kanayama: animal operation; Satoru Otsuru: interpretation of data; Masafumi Kashii: interpretation of data; Takahiro Makino: interpretation of data; Masayuki Furuya: interpretation of data; Kazuma Kitaguchi: interpretation of data; Ryota Chijimatsu: interpretation of data; Kosuke Ebina: interpretation of data; Hideki Yoshikawa: supervision.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI Grant 25861313). PTH 1-34 was kindly provided by Asahi Kasei (Tokyo, Japan), and rhBMP-2 was kindly provided by Osteopharma (Osaka, Japan).

References

- Arrington E.D., Smith W.J., Chambers H.G., Bucknell A.L., Davino N.A. Complications of iliac crest bone graft harvesting. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1996;329:300–309. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199608000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspenberg P., Genant H.K., Johansson T., Nino A.J., See K., Krohn K., García-Hernández P.A., Recknor C.P., Einhorn T.A., Dalsky G.P., Mitlak B.H., Fierlinger A., Lakshmanan M.C. Teriparatide for acceleration of fracture repair in humans: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study of 102 postmenopausal women with distal radial fractures. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010;25(2):404–414. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron R., Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 2013;19(2):179–192. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden S.D., Zdeblick T.A., Sandhu H.S., Heim S.E. The use of rhBMP-2 in interbody fusion cages. Definitive evidence of osteoinduction in humans: a preliminary report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(3):376–381. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200002010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden S.D., Kang J., Sandhu H., Heller J.G. Use of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 to achieve posterolateral lumbar spine fusion in humans: a prospective, randomized clinical pilot trial: Volvo award in clinical studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27(23):2662–2673. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canalis E. Update in new anabolic therapies for osteoporosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95(4):1496–1504. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canalis E., Giustina A., Bilezikian J.P. Mechanisms of anabolic therapies for osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357(9):905–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra067395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster D.W., Cosman F., Parisien M., Shen V., Lindsay R. Anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone on bone. Endocr. Rev. 1993;14(6):690–709. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-6-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fermor B., Skerry T.M. PTH/PTHrP receptor expression on osteoblasts and osteocytes but not resorbing bone surfaces in growing rats. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1995;10(12):1935–1943. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650101213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallacher S.J., Dixon T. Impact of treatments for postmenopausal osteoporosis (bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone, strontium ranelate, and denosumab) on bone quality: a systematic review. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2010;87(6):469–484. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jilka R.L. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH. Bone. 2007;40(6):1434–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaito T., Myoui A., Takaoka K., Saito N., Nishikawa M., Tamai N., Ohgushi H., Yoshikawa H. Biomaterials. 2005;26(1):73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaito T., Hohnson J., Ellerman J., Tian H., Aydogan M., Chatsrinopkun M., Ngo S., Choi C., Wang J.C. Synergistic effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2 and 7 by ex vivo gene therapy in a rat spinal fusion model. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2013;95(17):1612–1619. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya N., Ye L., Kobayashi T., Mochida Y., Yamauchi M., Kronenberg H.M., Feng J.Q., Mishina Y. BMP signaling negatively regulates bone mass through sclerostin by inhibiting the canonical Wnt pathway. Development. 2008;135(22):3801–3811. doi: 10.1242/dev.025825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsubara S., Mori S., Mashiba T., Nonaka K., Seki A., Akiyama T., Miyamoto K., Cao Y., Manabe T., Norimatsu H. Human parathyroid hormone (1-34) accelerates the fracture healing process of woven to lamellar bone replacement and new cortical shell formation in rat femora. Bone. 2005;36(4):678–687. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leahy P.D., Smith B.S., Easton K.L., Kawcak C.E., Eickhoff J.C., Shetye S.S., Puttlitz C.M. Correlation of mechanical properties within the equine third metacarpal with trabecular bending and multi-density micro-computed tomography data. Bone. 2010;46(4):1108–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.01.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manabe T., Mori S., Mashiba T., Kaji Y., Iwata K., Komatsubara S., Seki A., Sun Y.X., Yamamoto T. Human parathyroid hormone (1-34) accelerates natural fracture healing process in the femoral osteotomy model of cynomolgus monkeys. Bone. 2007;40(6):1475–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maycas M., Ardura J.A., de Castro L.F., Bravo B., Gortázar A.R., Esbrit P. Role of the parathyroid hormone type 1 receptor (PTH1R) as a mechanosensor in osteocyte survival. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015;30(7):1231–1244. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto T., Kaito T., Kashii M., Matsuo Y., Sugiura T., Iwasaki M., Yoshikawa H. Effect of intermittent administration of teriparatide (parathyroid hormone 1-34) on bone morphogenetic protein-induced bone formation in a rat model of spinal fusion. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2014;96(13) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima T., Hayashi M., Fukunaga T., Kurata K., Oh-Hora M., Feng J.Q., Bonewald L.F., Kodama T., Wutz A., Wagner E.F., Penninger J.M., Takayanagi H. Evidence for osteocyte regulation of bone homeostasis through RANKL expression. Nat. Med. 2011;17(10):1231–1234. doi: 10.1038/nm.2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer R.M., Arnaud C.D., Zanchetta J.R., Prince R., Gaich G.A., Reginster J.Y., Hodsman A.B., Eriksen E.F., Ish-Shalom S., Genant H.K., Wang O., Mitlak B.H. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344(19):1434–1441. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105103441904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Costa R., Favis H.M., Sorenson C. Defective cancellous bone structure and abnormal response to PTH in cortical bone of mice lacking Cx43 cytoplasmic C-terminus domain. Bone. 2015;81:632–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee Y., Allen M.R., Condon K., Lezcano V., Ronda A.C., Galli C., Olivos N., Passeri G., O'Brien C.A., Bivi N., Plotkin L., Bellido T. PTH receptor signaling in osteocytes governs periosteal bone formation and intracortical remodeling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;5:1035–1046. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson P.A., Wray A.C. Natural history of posterior iliac crest bone graft donation for spinal surgery: a prospective analysis of morbidity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(13):1473–1476. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200107010-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saini V., Marengi D.A., Barry K.J., Fulzele K.S., Heiden E., Liu X., Dedic C., Maeda A., Lotinun S., Baron R., Pajevic P.D. Parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide type 1 receptor signaling in osteocytes regulates anabolic and catabolic skeletal responses to PTH. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288(28):20122–20134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields L.B., Raque G.H., Glassman S.D., Campbell M., Vitaz T., Harpring J., Shields C.B. Adverse effects associated with high-dose recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 use in anterior cervical spine fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(5):542–547. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000201424.27509.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smucker J.D., Rhee J.M., Singh K., Yoon S.T., Heller J.G. Increased swelling complications associated with off-label usage of rhBMP-2 in the anterior cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(24):2813–2819. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000245863.52371.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann .J.C., Herkowitz H.N. Pseudarthrosis of the spine. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1992;284:80–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada I., Kouzmenko A.P., Kato S. Wnt and PPAR gamma signaling in osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2009;5(8):442–447. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam C.S., Heersche J.N., Murray T.M., Parsons J.A. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the bone apposition rate independently of its resorptive action: differential effects of intermittent and continuous administration. Endocrinology. 1982;110(2):506–512. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-2-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urist M.R. Bone formation by autoinduction. Science. 1965;150(3698):893–899. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3698.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.C., Kanim L.E., Yoo S., Campbell P.A., Berk A.J., Lieberman J.R. Effect of regional gene therapy with bone morphogenetic protein-2-producing bone marrow cells on spinal fusion in rats. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003;85(5):905–911. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200305000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozney J.M., Rosen V., Celeste A.J., Mitsock L.M., Whitters M.J., Kriz R.W., Hewick R.M., Wang E.A. Novel regulators of bone formation: molecular clones and activities. Science. 1988;242(4885):1528–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.3201241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B., Zhao X., Yang C., Crane J., Xian L., Lu W., Wan M., Cao X. Parathyroid hormone induces differentiation of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells by enhancing bone morphogenetic protein signaling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;27(9):2001–2014. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.L., Frangos J.A., Chachisvilis M. Mechanical stimulus alters conformation of type 1 parathyroid hormone receptor in bone cells. Am. J. Phys. Cell Physiol. 2009;296(6):C1391–C1399. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00549.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]