Abstract

Introduction

Cancer pathogenesis and resulting treatment may lead to bone loss and poor skeletal health in survivorship. The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the influence of 26 weeks of combined aerobic and resistance-training (CART) exercise on bone mineral density (BMD) in a multi-racial sample of female cancer survivors.

Methods

Twenty-six female cancer survivors volunteered to undergo CART for 1 h/day, 3 days/week, for 26 weeks. The Improving Physical Activity After Cancer Treatment (IMPAACT) Program involves supervised group exercise sessions including 20 min of cardiorespiratory training, 25 min of circuit-style resistance-training, and 15 min of abdominal exercises and stretching. BMD at the spine, hip, and whole body was assessed using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) before and after the intervention. Serum markers of bone metabolism (procollagen-type I N-terminal propeptide, P1NP, and C-terminal telopeptides, CTX) were measured at baseline, 13 weeks, and at study completion.

Results

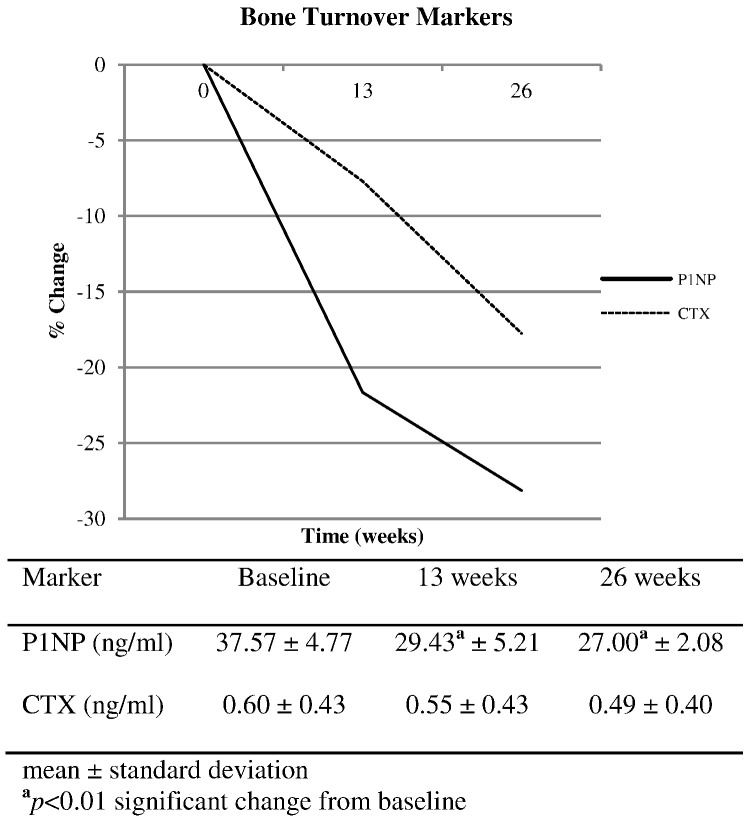

Eighteen participants, with the average age of 63.0 ± 10.3 years, completed the program. Mean duration since completion of cancer treatment was 6.2 ± 10.6 years. Paired t-tests revealed significant improvements in BMD of the spine (0.971 ± 0.218 g/cm2 vs. 0.995 ± 0.218 g/cm2, p = 0.012), hip (0.860 ± 0.184 g/cm2 vs. 0.875 ± 0.191 g/cm2, p = 0.048), and whole body (1.002 ± 0.153 g/cm2 vs. 1.022 ± 0.159 g/cm2, p = 0.002). P1NP declined 22% at 13 weeks and 28% at 26 weeks in comparison to baseline (p < 0.01) while CTX showed a non-significant decrease of 8% and 18% respectively.

Conclusions

We report significant improvements in BMD at the spine, hip, and whole body for female cancer survivors who completed 26 weeks of CART. This investigation demonstrates the possible effectiveness of CART at improving bone health and reducing risk of osteoporosis for women who have completed cancer treatment. The IMPAACT Program appears to be a safe and feasible way for women to improve health after cancer treatment.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; BTM, bone turnover marker; CART, combined aerobic and resistance training; CTX, C-terminal telopeptides; DXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; IMPAACT, improving physical activity after cancer treatment; P1NP, procollagen-type I N-terminal propeptides; NTX, N-telopeptide cross-linked collagen type I

Keywords: Bone mineral density, Osteoporosis, Oncology, Cancer-induced bone loss, Bone turnover markers

Highlights

-

•

Combined aerobic and resistance training improves BMD in female cancer survivors.

-

•

Participants who had chemotherapy showed significantly greater improvements in BMD.

-

•

P1NP and CTX exhibit an inverse relationship with gains in BMD after exercise.

1. Introduction

Improvements in cancer treatment and detection, as well as growth of the population, have led to increased survival rates among those diagnosed with cancer. As of 2014, there was an estimated 14.5 million cancer survivors in the United States, 64% who are 5-year survivors, while 15% are 20-year survivors [1]. Cancer survivors are living longer but experience greater comorbidity than age-matched peers who never had cancer. Survivors demonstrate comorbidities such as higher rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis 2, 3, 4. Osteoporosis is a chronic disease of low bone mass, characterized by skeletal fragility and increased risk for fracture. Women experience a greater burden of this disease accounting for 80% of people with osteoporosis.

Previous research reports that 12 months of treatment for a gynecological cancer can cause 6–10% reduction in bone mineral density (BMD) due to elevated resorption during treatment [5]. Elevated resorption and its associated loss in BMD increases risk for fracture. In fact, women with a history of breast cancer experience significantly more skeletal fractures than women who never had breast cancer [6]. Bone loss during cancer treatment appears to be in addition to losses experienced with cessation of ovarian function. Survivors of gynecological cancers, who were diagnosed before menopause and underwent ovarectomy, demonstrate 7–9% lower BMD than similarly aged women who underwent an ovariectomy for non-cancerous reasons [7].

Cancer and its treatment may lead to poor skeletal health via several mechanisms. Secretions from tumors themselves can speed up osteoclast activity, increasing bone resorption [8]. This interference with normal bone signaling pathways is observed in both male and female cancer survivors and is frequently quantified as an elevated serum level of P1NP 9, 10. Subsequently, P1NP is valuable as both an indicator of risk for tumor invasion of the bone and as a traditional bone turnover marker (BTM) for measuring skeletal response to pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions for poor BMD. For cancer patients, assessment of both the possibility for metastasis and normal/abnormal BMD are essential to promoting skeletal health during survivorship. In addition to the aforementioned burden of tumor interference, female cancer patients frequently encounter additional skeletal health challenge due to the surgery or chemotherapy necessary for cancer treatment which may also induce ovarian dysfunction and lead to early menopause and its associated bone loss [11]. Also, long-term use of antihormonal medications, which are often part of the cancer therapy, negatively impact bone health [6]. All of the mechanisms discussed here will have systemic influence on bone health, however radiation treatment can cause site-specific bone loss [12].

Multiple studies have demonstrated that weight-bearing exercise can improve or help maintain BMD and lower risk for fracture in pre and postmenopausal women 13, 14. Weight-bearing aerobic activities and resistance training performed multiple times per week are recommended to help preserve bone health during adulthood [15]. In addition, some research supports use of whole body vibration as a training method which may potentially be osteogenic 16, 17. Exercise is a nonpharmacological, low-cost approach, with the potential to improve or maintain bone health and additional likely benefits to cardiovascular fitness, body weight management, balance, and risk for falling. Exercise programming which combines aerobic and resistance training exercise may simultaneously help to address multiple comorbidities of cancer such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis. Little is known about the volume of exercise that is safe for cancer survivors and that is effective at maintaining or improving bone health [18]. With the recent increase in the number of cancer survivors and the multiple ways cancer and its treatment may affect the skeleton, there is a need to develop survivorship care plans which include exercise as a means to sustain bone health in women and reduce comorbidities. Therefore, the purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the influence of 26 weeks of combined aerobic and resistance-training (CART) exercise on bone mineral density (BMD) in a convenience sample of female cancer survivors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical approval

The IMPAACT Study was approved by the Human Subject's Institutional Review Board at Loyola Marymount University. All research participants provided written informed consent. Procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Loyola Marymount University Institutional Review Board which uses the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments as ethical standards.

2.2. Participants and anthropometrics

The Improving Physical Activity After Cancer Treatment (IMPAACT) Study recruited 26 female cancer survivors from the Los Angeles area to participate in the exercise intervention using convenience sampling and physician referral. Eighteen of the volunteers completed the 26-week intervention including testing at baseline and follow up. Volunteers were excluded if currently receiving intravenous chemotherapy or outpatient radiation therapy. Primary care physicians and oncologists were notified of their patient's participation. Weight and height were assessed in minimal clothing, without shoes, where weight was measured on an electronic scale (Tanita BWB-927A Tokyo, Japan) and height was assessed using a stadiometer (Seca Accu-Hite, Columbia, MD, USA). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kg by height in meters squared.

2.3. Assessments

Demographic characteristics and medical history were obtained at baseline via self-administered questionnaires. The Aerobic Center Longitudinal Study Physical Activity Questionnaire was used to assess regular physical activity by calculating metabolic equivalents in hours per week by using intensity of activity, age, body weight, and duration [19]. The Block 2005 Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) was used to measure dietary intake over the previous year for nutrients important for bone health, including calcium and vitamin D. This questionnaire uses photos to help users more accurately estimate portion size and has been validated to assess dietary intake over the previous 12 months [20].

2.4. Bone health and body composition

Bone mineral density of the posterior-anterior spine, left hip, and whole body were measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA, Hologic Discovery A, Waltham, MA). One technician performed and analyzed all scans. This technician demonstrates 1.0% test-retest reliability for BMD at the hip and spine. The whole body DXA scan allows for analysis of lean mass and fat mass. Participants provided fasting blood samples early in the morning at baseline, 13 weeks, and 26 weeks. Serum samples were processed and stored at − 20 °C within 2 h of collection and moved for long-term storage at − 80 °C, 24 h later. Procollagen-type I N-terminal propeptide (P1NP, ng/mL) a measure of bone formation cleaved off in production of type I collagen was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from Cloud Clone Corp (Houston, TX). Serum levels of C-terminal telopeptides (CTX, ng/mL) were measured as a marker of bone resorption via ELISA kits from Immuno Diagnostic Systems (Fountain Hills, AZ). Bone turnover markers (BTMs) were assayed at the UCLA Bone Histomorphometry Laboratory with coefficients of variation (CV) as follows PINP inter-assay CV of < 12%, P1NP intra-assay CV of < 10%, CTX inter-assay CV of 2.5–10.9%, and CTX intra-assay CV of 1.8–3.0%.

2.5. Exercise program

The IMPAACT Study was a combined aerobic and resistance training program which occurred 1 h per day, 3 days per week, for 26 weeks. The supervised exercise intervention took place on the Loyola Marymount University campus in Los Angeles, CA following the academic calendar; beginning in August/September, taking a break for winter and spring holidays, then concluding in April/May. Therefore, the 26-week exercise program was actually spread over 32 weeks of the year. Prescribed in accordance with Guidelines for Exercise for Cancer Survivors from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), each supervised exercise session includes a) 20 min of cardiorespiratory training, b) 25 min of circuit-style resistance training, and c) 15 min of exercises for the core musculature with dynamic and static stretching [21]. The IMPAACT study intervention incorporated both aerobic and resistance training components, in effort to meet the American College of Sports Medicine Guidelines on Exercise for Cancer Survivors and to help to reduce the multiple comorbidities exhibited by cancer survivors.

Cardiorespiratory training included walking although weather and fitness levels required the occasional inclusion of elliptical machines, or stationary bicycles at a prescribed target hear rate training zone of 35–80% heart rate reserve. In accordance with baseline activity levels, physical fitness, and medical history, prescribed cardiovascular intensity was determined using the Karvonen formula [exercise target heart rate = (heart rate reserve) × % of target exercise intensity + heart rate at rest)]. Heart rates from chest-strap monitors (RS800CX, Polar Electro, Lake Success, NY) were obtained for each participant multiple times during the cardiorespiratory training and ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) values were obtained at the end of the cardiorespiratory portion and re-evaluated for progression every 2–3 weeks [22]. At the start of the program participants were prescribed values of 35–50% of heart rate reserve but were progressively increased over time based on heart rate and RPE relationships.

The resistance training circuit included eight upper and lower body resistance exercises provided through use of body weight, dumbbells, elastic bands, varied body positions, and altered step height. Exercises included upper body rows, squats, step-ups, push-ups, lunges, resisted shoulder and hip abduction movements, and balance drills. Participants were introduced to the 10-station resistance-training circuit over a two-week period and by the third week performed each exercise for 45 s followed by 20 s rest in a circuit fashion, achieving three sets of each exercise during the workout. Utilizing the circuit-style of resistance training, exact numbers of repetitions were not recorded, however coaching and supervision would suggest movement speeds consistent with 12–15 repetitions per set. Load and repetitions were guided by RPE and individual HR zone prescription. To ensure safety, participants aimed to reach exertion of 7–8 (out of 10) on the RPE scale while maintaining HR in close proximity to their prescribed HR zone. Participants self-monitored both variables and were encouraged to modify exercise by altering the number of repetitions or adjusting resistance in order to comply with aforementioned recommendations. Whole body vibration on a Vibraflex 550 platform (Novotec, Pforzheim, Germany) was included as two stations in each circuit. Whole body vibration commenced at 30 s and 20 Hz for the first 4 weeks and advanced to 45 s and 25 Hz with participants performing straightforward movements such as toe/heel raises and partial squats simultaneously during vibration exposure. The program was carefully supervised by research assistants to ensure exercise adherence and training increased intensity every two to three weeks.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Paired t-tests, performed with SPSS version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA), were used to evaluate significant changes in BMD from baseline to follow up. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate change in P1NP and CTX over time.

3. Results

Twenty-six female cancer survivors volunteered to participate in the exercise intervention, while 18 completed 26 weeks of the exercise intervention and the follow-up assessments. Three volunteers withdrew from the program due to cancer recurrence and return to treatment. Three participants were unable to complete the full 26 week IMPAACT program because they underwent post-treatment reconstructive surgeries that required downtime from exercise. Two volunteers dropped from the study due to scheduling conflicts with work and personal matters. Baseline characteristics for the 18 participants who completed baseline and follow-up testing are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics at baseline.

| Characteristic | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.0 | 10.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.0 | 7.0 |

| Calcium intake (mg/d) | 1179 | 600 |

| Vitamin D intake (IU/d) | 621 | 268 |

| Physical activity (MET-h/wk) | 19.2 | 12.0 |

| Spine T-score | − 1.01 | 1.82 |

| Total hip T-score | − 0.86 | 1.26 |

| Time since treatment (years) | 6.2 | 10.6 |

| Chemotherapy (% yes) | 44% | |

| Radiation therapy (% yes) | 72% | |

| Surgical treatment (% yes) | 83% |

BMI is body mass index.

MET is metabolic equivalents.

Twelve participants identified their race/ethnicity as White, five identified as Black/African American, and one Hispanic/Latina. Most volunteers were treated for breast cancer (n = 12, 67%), while other cancer types included colorectal (n = 3, 17%), Hodgkin's lymphoma (n = 1, 5%), thyroid (n = 1, 5%), and both breast and colon cancer (n = 1, 5%). Table 1 displays the percent of participants who underwent surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation as a treatment. All participants experienced one of these treatments and many experienced two or more. Most of the participants (89%) had undergone menopause before the study began, however two volunteers were premenopausal. The average time since menopause was 17.1 ± 9.9 years. At baseline, four participants were taking a medication known to alter bone health; 1 was taking a bisphosphonate, 1 was taking prednisone, 2 participants were taking an aromatase inhibitor one of which was also taking a RANK ligand inhibitor (denosumab). During the study, two additional participants initiated oral bisphosphonate medication use weekly while one volunteer ceased the aromatase inhibitor. The average recorded attendance for the exercise sessions was 63% ± 17.3. No injuries or adverse effects due to the CART exercise sessions were reported by participants.

The average body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) is presented in Table 1. Most participants were obese (n = 9, 50%) or overweight (n = 6, 33%), while two were of normal body weight for their height, and one was underweight (BMI ≤ 18.5). Data presented in Table 1 for calcium and vitamin D intake includes dietary and supplemental sources of these nutrients. The average calcium intake appeared to be adequate for most adults; 1000 mg/day for ages 19–50, however only 50% of volunteers were achieving the recommended daily allowance (RDA) for their age (1200 mg/day for ages 51 +) [23]. Similar results are reported for vitamin D intake. The average consumption for all participants met the RDA, however 44% (n = 8) did not achieve the desirable intake set by the Institute of Medicine.

When implementing the World Health Organization's definitions for osteopenia and osteoporosis [24], bone scan results from baseline reveal that 41% of participants (n = 7) and 24% (n = 4) were osteopenic or osteoporotic at the spine, respectively. At the hip, 56% (n = 10) were osteopenic while another 17% (n = 3) met the criteria for diagnosis of osteoporosis. No significant changes in body weight occurred during the exercise intervention (80.2 ± 20.0 vs. 81.2 ± 19.4, p = 0.32).

Paired t-tests comparing baseline values to those obtained after 26 weeks of training revealed significant improvements in BMD at the spine, hip, and whole body (Table 2). As a collective group, participants experienced a 2.5% improvement in BMD at the spine, 1.7% at the hip, and 2.0% of the whole body. Variables at baseline such as age, time since treatment, physical activity, BMI, calcium and vitamin D intake were not correlated to changes in BMD. When examining results by treatment type, participants who underwent chemotherapy (n = 8), experienced significantly greater improvements in BMD at the spine (0.2% vs. 4.9%, p < 0.05) and hip (0.2% vs. 3.6%, p < 0.05) in comparison to participants who did not have chemotherapy treatment (n = 10) but had radiation or surgery or both. Body composition derived from the whole body DXA scan is also displayed in Table 2. Participants showed significant improvements in lean mass over the course of the study adding nearly 1 kg of lean mass; however fat mass was maintained during the intervention leading to no significant change in percent body fat.

Table 2.

Changes in bone mineral density and body composition.

| Measurement | Baseline | Follow-up | p-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total spine BMD | 0.971 ± 0.218 | 0.995 ± 0.218 | 0.012 |

| Total hip | 0.860 ± 0.184 | 0.875 ± 0.191 | 0.048 |

| Whole body | 1.002 ± 0.153 | 1.022 ± 0.159 | 0.002 |

| Lean mass | 43.8 ± 8.7 | 44.7 ± 8.4 | 0.044 |

| Fat mass | 35.2 ± 12.6 | 35.2 ± 12.6 | 0.990 |

Mean ± standard deviation.

BMD is bone mineral density in g/cm2 at the bone sites indicated.

Lean mass and fat mass of the whole body are in kg.

p-Value is displayed for a paired t-test conducted with SPSS version 22.

Analysis of serum markers of bone turnover indicated a decrease in bone metabolism during the exercise intervention (Fig. 1). P1NP was 22% lower at 13 weeks and 28% lower at 26 weeks in comparison to baseline (p < 0.01). CTX showed a non-significant decrease of 8% and 18%, 13 and 26 weeks after the start of the study, respectively. Further analysis involving the removal of participants who were taking a medication known to alter bone metabolism did not change these findings.

Fig. 1.

Bone turnover markers.

4. Discussion

The goal of this investigation was to evaluate the effectiveness of 26 weeks of CART on BMD in female cancer survivors. We report significant improvements in BMD at the spine, hip, and whole body in this convenience sample of females. Participants also experienced a significant increase in lean mass while showing maintenance of fat mass. A lack of adverse events and injuries during the IMPAACT program supports exercise as a safe way to improve health after cancer treatment.

Two investigations 25, 26 report improvement in BMD at the hip and spine in breast cancer survivors who performed strength training exercise twice per week for 12 months, but their participants also began bisphosphonate medication with calcium and vitamin D supplementation when initiating the exercise program. Additional benefits due to exercise without bisphosphonate medication use were not observed [25]. Other investigations involving walking [27], aerobic exercise [28], and resistance-training with a jumping protocol 29, 30, 31 have demonstrated that exercise may help maintain bone health in cancer survivors.

Research shows that most women over the age of 40, lose an average of 0.5% bone mass per year [15]. Several other researchers have reported maintenance of bone mass with an exercise intervention in female cancer survivors of similar age to ours 25, 29, 30. However, our participants, at the average age of 60 years (range: 40 to 80 years), not only maintained bone mass but appear to have increased in bone mineral density. Perhaps our participants experienced a measureable increase in BMD because the weight-bearing exercises were precisely selected for their potential to impact the skeleton. The 1.7–2.5% average increase in BMD corresponds to improvements in T-scores at all bone sites and may result in a clinically relevant reduction in future risk for fracture [32]. In addition, incorporation of whole body vibration training is novel and may have contributed to the osteogenic response. Percent change in BMD should be interpreted with knowledge of the 1.0% coefficient of variation in DXA bone measurements.

The IMPAACT program was developed to investigate the rehabilitative potential of supervised exercise on a comprehensive set of neural, muscular, metabolic, as well as skeletal variables. Therefore, in order to address the multiple comorbidities associated with cancer survivorship, we created an exercise intervention which involved aerobic and resistance training, according to guidelines for exercise in cancer survivors set forth by the ACSM [21]. It is well accepted that weight-bearing activity, including aerobic exercise and resistance training, can help preserve bone health in adults [15]. Previous research among female cancer survivors has suggested that weight-bearing aerobic exercise [18] and resistance training combined with impact exercise (jumping) helps to preserve BMD 30, 31. It is likely that for healthy adults, walking alone is not a sufficient stimulus to contribute to improvements in bone health, but may help improve cardiovascular fitness and/or preserve current bone mass [33]. Galvao et al. investigated combined aerobic and resistance training in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer [34]. In comparison to normal care, the CART intervention of Galvao et al. led to improved cardiovascular capacity, lean mass, and strength despite the hypogonadal status involved with prostate cancer treatment (BMD was not a component of their investigation). Schwartz et al. found that aerobic weight-bearing exercise, such as walking and jogging, preserved BMD better than resistance exercise and usual care during active chemotherapy treatment in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer [35]. Exercise selection and adherence involved with their home-based program and the current treatment status of their participants could explain the lack of skeletal benefit with the resistance exercise.

Subsequent analysis of BMD results in our participants by treatment type revealed that those who underwent chemotherapy displayed significantly greater improvements in bone mass during the exercise intervention than those who did not have chemotherapy. Deeper analysis of bone health changes for those who underwent surgery or radiation revealed no additional meaningful information. Research by Winters-Stone et al. suggests that women with low initial values of BMD have greater improvements in bone health due to exercise [13]. Further investigation confirmed that this does not explain discrepant results by treatment type in our participants, as baseline BMD values were similar or slightly higher for those who had chemotherapy in comparison to those who did not. Considering our small sample size, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding this secondary finding; however it warrants further investigation as to the skeletal benefits of weight-bearing exercise by treatment type in cancer survivors.

The International Osteoporosis Foundation recommends serum measurements of P1NP and CTX for interventional studies of bone health [36]. P1NP and CTX values reported for participants in our study were within the expected reference intervals reported in the literature [37]. However, few studies have reported BTMs in cancer survivors, a group at risk for poor bone health 7, 38. Greenspan et al. reported similar decreases in P1NP and N-telopeptide cross-linked collage type I (NTX) in breast cancer survivors who underwent 12-months of treatment with risendronate [39]. In another study of breast cancer survivors, Toriola et al. reported significant decreases in P1NP and NTX markers, but no significant change in CTX, for overweight and obese women undergoing a weight loss intervention which included exercise for some participants [40]. In contrast to our findings, their results showed a greater decrease at 12 months rather than 6 months, as the rate of change in BTMs for our participants seemed to plateau in the latter half of our intervention.

Eekman et al. report significant reductions in P1NP and CTX for men and women with osteoporosis who underwent three months of bisphosphonate treatment [41]. The 28% and 18% reduction in formation and resorption markers in our population was not as large as those reported for Eekman et al. however we postulate that the changes in our study are due to the exercise intervention, a conservative treatment approach to osteoporosis, rather than pharmacological therapy. Research by Shah et al. complements our work in reporting a decrease in P1NP and CTX for research participants who participated in a combined aerobic and resistance training program for 1 year [42]. Similar to our findings, the most drastic change in BTMs occurred in the first six months of the study which may have led to the measureable improvements in BMD at 12 months reported by Shah el al. and after 26 weeks of training as we report here. A decrease in bone resorption, although non-significant in our findings, may have long-term benefits for bone health, especially in a mostly postmenopausal population such as ours where resorption can be high due to menopausal status. Increase in BTMs can identify women at risk for fracture due to bone loss, especially at clinically relevant sites such as the hip and spine. Therefore a decrease in BTMs, as seen in our population, is congruent with the improvements in BMD as changes in BTMs are apparent well before changes in BMD.

A limitation of this investigation is the lack of a non-exercising comparison group. It is possible that all cancer survivors would experience a rebound in bone mass after completion of treatment, however to our knowledge, this has never been reported in the literature. Considering that time since treatment was unrelated to change in bone mineral density and our participants had a mean of 6 years post-treatment, it is unlikely that the positive changes in bone health reported here were simply due to recovery time rather than the intervention. It is possible, that our participants would have displayed greater improvements in bone mass due to an interaction effect of diet and exercise, if everyone had been meeting the recommended daily allowance for calcium and vitamin D, nutrients known to be important for bone health. Additionally, we measured dietary intake of vitamin D, which does not always reflect serum vitamin D status due to the ability to synthesize the hormone from ultraviolet sun exposure. With our location in southern California, it is possible that vitamin D status is adequate despite poor dietary intake. Also, more than half of our participants performed their aerobic activity for 20 min, three days/week, outside at noontime, possibly increasing their exposure to ultraviolet light. On the other hand, mature adults synthesize vitamin D less efficiently and cancer survivors could make a conscientious effort to avoid sun exposure in attempt to reduce future risk of skin cancer [23]. Furthermore, previous research suggests that physical activity can be osteogenic at calcium intakes ~ 1000 mg/d [43]. While 50% of our participants were not meeting the RDA for their age, 66% were achieving the 1000 mg/d threshold. Additional research suggests that weight-bearing exercise is more influential on bone health than adequate calcium intake [44]. Future investigations would improve upon this work by implementing a larger sample size, limiting inclusion to one type of cancer, examining differential effects of the mode of exercise, incorporating a non-exercising comparison group, and assessing serum levels of vitamin D.

5. Conclusions

These results suggest that CART is safe and feasible for female cancer survivors and could help improve bone health. With the increased number of women surviving cancer and experiencing cancer-induced bone loss, survivorship care plans need to include exercise as a means to maintain or improve bone health and reduce risk for osteoporosis in female cancer survivors.

Conflicts of interest

No authors declare a conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the participants of the Loyola Marymount University (LMU) IMPAACT Study. Danielle Good-Dawson, M. Derek Pugh, Isabela Kuroyama, and the undergraduate research assistants were instrumental in the success of this program. We also acknowledge Dr. Arash Asher, Director of Cancer Survivorship and Rehabilitation at Cedars-Sinai. This work was funded by Tower Cancer Research Foundation, QueensCare Health Foundation, LMU Seaver College of Science and Engineering, LMU Rains Research Fund, and the LMU Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program and Summer Undergraduate Research Programs. Multiplex assays were performed at the UCLA Bone Histomorphometry Laboratory with funding from the National Institutes of Health (1R03DK098627-01 and K23DK080984-01A1), Genentech, American Society of Nephrology's Norman Siegel Investigator Award, and the Children's Discovery and Innovation Institute/David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

References

- 1.DeSantis C.E., Lin C.C., Mariotto A.B., Siegel R.L., Stein K.D., Kramer J.L., Alteri R., Robbins A.S., Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014;64:252–271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leach C.R., Weaver K.E., Aziz N.M., Alfano C.M., Bellizzi K.M., Kent E.E., Forsythe L.P., Rowland J.H. The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:239–251. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarleton H.P., Ryan-Ibarra S., Induni M. Chronic disease burden among cancer survivors in the California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2009–2010. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:448–459. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0350-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver K.E., Foraker R.E., Alfano C.M., Rowland J.H., Arora N.K., Bellizzi K.M., Hamilton A.S., Oakley-Girvan I., Keel G., Aziz N.M. Cardiovascular risk factors among long-term survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic cancers: a gap in survivorship care? J. Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0267-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishio K., Tanabe A., Maruoka R., Nakamura K., Takai M., Sekijima T., Tunetoh S., Terai Y., Ohmichi M. Bone mineral loss induced by anticancer treatment for gynecological malignancies in premenopausal women. Endocr Connect. 2013;2:11–17. doi: 10.1530/EC-12-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taxel P., Choksi P., Van Poznak C. The management of osteoporosis in breast cancer survivors. Maturitas. 2012;73:275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stavraka C., Maclaran K., Gabra H., Agarwal R., Ghaem-Maghami S., Taylor A., Dhillo W.S., Panay N., Blagden S.P. A study to evaluate the cause of bone demineralization in gynecological cancer survivors. Oncologist. 2013;18:423–429. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blake M.L., Tometsko M., Miller R., Jones J.C., Dougall W.C. RANK expression on breast cancer cells promotes skeletal metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2014;31:233–245. doi: 10.1007/s10585-013-9624-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean-Colomb W., Hess K.R., Young E., Gornet T.G., Handy B.C., Moulder S.L., Ibrahim N., Pusztai L., Booser D., Valero V., Hortobagyi G.N., Esteva F.J. Elevated serum P1NP predicts development of bone metastasis and survival in early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013;137:631–636. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2374-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thurairaja R., Iles R.K., Jefferson K., McFarlane J.P., Persad R.A. Serum amino-terminal propeptide of type 1 procollagen (P1NP) in prostate cancer: a potential predictor of bone metastases and prognosticator for disease progression and survival. Urol. Int. 2006;76:67–71. doi: 10.1159/000089738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vehmanen L.K., Elomaa I., Blomqvist C.P., Saarto T. The effect of ovarian dysfunction on bone mineral density in breast cancer patients 10 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:75–79. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.792992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gralow J.R., Biermann J.S., Farooki A., Fornier M.N., Gagel R.F., Kumar R., Litsas G., McKay R., Podoloff D.A., Srinivas S., Van Poznak C.H. NCCN Task Force Report: Bone Health in Cancer Care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(Suppl 3: S1–50) doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0215. quiz S51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winters-Stone K.M., Snow C.M. Musculoskeletal response to exercise is greatest in women with low initial values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1691–1696. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000089338.66054.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snow C.M., Shaw J.M., Winters K.M., Witzke K.A. Long-term exercise using weighted vests prevents hip bone loss in postmenopausal women. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000;55:M489–M491. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.9.m489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohrt W.M., Bloomfield S.A., Little K.D., Nelson M.E., Yingling V.R. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand: physical activity and bone health. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1985–1996. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000142662.21767.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ligouri G.C., Shoepe T.C., Almstedt H.C. Whole body vibration training is osteogenic at the spine in college-age men and women. Journal of human kinetics. 2012;31:55–68. doi: 10.2478/v10078-012-0006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slatkovska L., Alibhai S.M., Beyene J., Cheung A.M. Effect of whole-body vibration on BMD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 2010;21:1969–1980. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1228-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winters-Stone K.M., Schwartz A., Nail L.M. A review of exercise interventions to improve bone health in adult cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:187–201. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pereira M.A., FitzerGerald S.J., Gregg E.W., Joswiak M.L., Ryan W.J., Suminski R.R., Utter A.C., Zmuda J.M. A collection of Physical Activity Questionnaires for health-related research. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1997;29:S1–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartman A.M., Block G., Chan W., Williams J., McAdams M., Banks W.L., Jr., Robbins A. Reproducibility of a self-administered diet history questionnaire administered three times over three different seasons. Nutr. Cancer. 1996;25:305–315. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, Irwin ML, Wolin KY, Segal RJ, Lucia A, Schneider CM, von Gruenigen VE, Schwartz AL, American College of Sports M. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010;42: 1409–26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Borg G., Linderholm H. Perceived exertion and pulse rate during graded exercise in various age groups. Acta Medica Scandinavica. 1967;181:194–206. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medicine Io . Brief Report. National Academy Press; Washington D.C.: 2011. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karaguzel G., Holick M.F. Diagnosis and treatment of osteopenia. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2010;11:237–251. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waltman N.L., Twiss J.J., Ott C.D., Gross G.J., Lindsey A.M., Moore T.E., Berg K., Kupzyk K. The effect of weight training on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors with bone loss: a 24-month randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos. Int. 2010;21:1361–1369. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1083-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waltman N.L., Twiss J.J., Ott C.D., Gross G.J., Lindsey A.M., Moore T.E., Berg K. Testing an intervention for preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2003;35:333–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knobf M.T., Insogna K., DiPietro L., Fennie C., Thompson A.S. An aerobic weight-loaded pilot exercise intervention for breast cancer survivors: bone remodeling and body composition outcomes. Biol Res Nurs. 2008;10:34–43. doi: 10.1177/1099800408320579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irwin M.L., Alvarez-Reeves M., Cadmus L., Mierzejewski E., Mayne S.T., Yu H., Chung G.G., Jones B., Knobf M.T., DiPietro L. Exercise improves body fat, lean mass, and bone mass in breast cancer survivors. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobek J., Winters-Stone K.M., Bennett J.A., Nail L. Musculoskeletal changes after 1 year of exercise in older breast cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:304–311. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winters-Stone K.M., Dobek J., Nail L., Bennett J.A., Leo M.C., Naik A., Schwartz A. Strength training stops bone loss and builds muscle in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011;127:447–456. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1444-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winters-Stone K.M., Dobek J., Nail L.M., Bennett J.A., Leo M.C., Torgrimson-Ojerio B., Luoh S.W., Schwartz A. Impact + resistance training improves bone health and body composition in prematurely menopausal breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos. Int. 2013;24:1637–1646. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasnich R.D., Miller P.D. Antifracture efficacy of antiresorptive agents are related to changes in bone density. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;85:231–236. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.1.6267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asikainen T.M., Kukkonen-Harjula K., Miilunpalo S. Exercise for health for early postmenopausal women: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Sports Med. 2004;34:753–778. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galvao D.A., Taaffe D.R., Spry N., Joseph D., Newton R.U. Combined resistance and aerobic exercise program reverses muscle loss in men undergoing androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer without bone metastases: a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:340–347. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz A.L., Winters-Stone K., Gallucci B. Exercise effects on bone mineral density in women with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2007;34:627–633. doi: 10.1188/07.ONF.627-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vasikaran S., Cooper C., Eastell R., Griesmacher A., Morris H.A., Trenti T., Kanis J.A. International Osteoporosis Foundation and International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine position on bone marker standards in osteoporosis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2011;49:1271–1274. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vasikaran S.D., Chubb S.P., Ebeling P.R., Jenkins N., Jones G.R., Kotowicz M.A., Morris H.A., Schneider H.G., Seibel M.J., Ward G. Harmonised Australian reference intervals for serum PINP and CTX in adults. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2014;35:237–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Conde D.M., Costa-Paiva L., Martinez E.Z., Mendes P.-N.A. Low bone mineral density in middle-aged breast cancer survivors: prevalence and associated factors. Breast Care (Basel) 2012;7:121–125. doi: 10.1159/000337763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenspan S.L., Bhattacharya R.K., Sereika S.M., Brufsky A., Vogel V.G. Prevention of bone loss in survivors of breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92:131–136. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toriola A.T., Liu J., Ganz P.A., Colditz G.A., Yang L., Izadi S., Naughton M.J., Schwartz A.L., Wolin K.Y. Effect of weight loss on bone health in overweight/obese postmenopausal breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015;152:637–643. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3496-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eekman D.A., Bultink I.E., Heijboer A.C., Dijkmans B.A., Lems W.F. Bone turnover is adequately suppressed in osteoporotic patients treated with bisphosphonates in daily practice. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2011;12:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah K., Armamento-Villareal R., Parimi N., Chode S., Sinacore D.R., Hilton T.N., Napoli N., Qualls C., Villareal D.T. Exercise training in obese older adults prevents increase in bone turnover and attenuates decrease in hip bone mineral density induced by weight loss despite decline in bone-active hormones. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:2851–2859. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Specker B.L. Evidence for an interaction between calcium intake and physical activity on changes in bone mineral density. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1996;11:1539–1544. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Welch J.M., Turner C.H., Devareddy L., Arjmandi B.H., Weaver C.M. High impact exercise is more beneficial than dietary calcium for building bone strength in the growing rat skeleton. Bone. 2008;42:660–668. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.12.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]