Abstract

Rationale: Little is known about the long-term effects of air pollution exposure and the root causes of asthma. We use exposure to intense air pollution from the 1952 Great Smog of London as a natural experiment to examine both issues.

Objectives: To determine whether exposure to extreme air pollution in utero or soon after birth affects asthma development later in life.

Methods: This was a natural experiment using the unanticipated pollution event by comparing the prevalence of asthma between those exposed to the Great Smog in utero or the first year of life with those conceived well before or after the incident and those residing outside the affected area at the time of the smog.

Measurements and Main Results: Prevalence of asthma during childhood (ages 0–15) and adulthood (ages >15) is analyzed for 2,916 respondents to the Life History portion of the English Longitudinal Study on Aging born from 1945 to 1955. Exposure to the Great Smog in the first year of life increases the likelihood of childhood asthma by 19.87 percentage points (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.37–36.38). We also find suggestive evidence that early-life exposure led to a 9.53 percentage point increase (95% CI, −4.85 to 23.91) in the likelihood of adult asthma and exposure in utero led to a 7.91 percentage point increase (95% CI, −2.39 to 18.20) in the likelihood of childhood asthma.

Conclusions: These results are the first to link early-life pollution exposure to later development of asthma using a natural experiment, suggesting the legacy of the Great Smog is ongoing.

Keywords: asthma, air pollution, early-life exposure, Great Smog

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Although the episodic triggers of asthma are widely known, the root causes of the condition itself are poorly understood. Evidence on the long-term impacts of exposure to air pollution is also limited. The 1952 London Smog provides a natural experiment for studying the underlying cause of asthma and the long-term effects of air pollution exposure very early in life, while limiting threats from statistical confounding.

What This Study Adds to the Field

We find that children exposed to the intense air pollution within the first year of life were more likely to develop asthma during both childhood and adulthood. Extreme air pollution events remain a concern today, with such places as Beijing experiencing the highest recorded levels of air pollution as recently as November 2015. Such events have an immediate impact on population health and an effect on health many years later. Evidence about the role of early-life exposure to air pollution as a root cause of asthma provides policy makers and physicians with new insights about how to prevent and potentially address the growing prevalence of the condition.

The Great London Smog of 1952 changed the course of environmental science and policy.1 Original analyses and reanalyses have demonstrated that the air pollution concentrations that resulted from an unanticipated temperature inversion from December 5–9, 1952, had immediate, detrimental effects on population health (1–3). During this incident, pollution concentrations exceeded current regulations and guidelines by a factor of 5–23 (3). Part of what has made the study of this “killer fog” so convincing is that its timing and severity were unexpected, with the extent of damage not recognized until after the smog dissipated (4). This made the occurrence of the elevated pollution concentrations “a grand experiment” in the spirit of John Snow (5, 6), ripe for understanding the causal effect from exposure.

Although much research has examined the immediate effects of exposure to the Great Smog on outcomes, such as mortality and respiratory disease, very little, if any, has explored the long run effects from exposure. Of particular interest are the potential long run impacts on children exposed during the early stages of life, because health insults during this critical period may cause significant, long-lasting harm (7, 8). In this paper, we examine the relationship between early childhood exposure to the Great Smog and the development of asthma later in life. Asthma is of particular interest because, although factors leading to asthma exacerbation are well understood, much less is known about the underlying causes of asthma (9–11). The results of this study have not been reported in any prior abstract or paper.

Methods

Data

This study relies on a combination of publicly available and special use data from ELSA (the English Longitudinal Study on Aging), a nationally representative survey of the English population aged 50 years and older (12). ELSA collects longitudinal data relating to health, social, and economic outcomes. The Life History survey, the source of the asthma outcomes used in the current study, was undertaken in 2007 as part of the third wave of ELSA surveys.

The first wave of the survey, undertaken in 2002, only covered those born before March 1, 1952. With wave three of ELSA, an additional sample of residents older than 50 was added, randomly selected from those born between March 1, 1953, and February 28, 1956. Although the random ELSA sample in wave three omits people born between March 1, 1952, and February 28, 1953, the partners of sampled individuals born in this period are included in the data and used in our analysis (13).

Focusing on children conceived within a few years of the Great Smog, we use year and month of birth, obtained from special use data, to pinpoint the timing of the child’s potential exposure to the smog. Special use data on first place of residence is used to identify children who resided in London at the time of their birth. Individuals are coded as “born in London” if their first residence was reported within the current bounds of the M25 London Orbital Motorway; we also explore alternative definitions for whether the respondent was born in London.

Of the 7,855 respondents to the Life History interview, we focus on 2,916 born between 1945 and 1955 with an identifiable first place of residence (208 respondents were dropped because of insufficient information). In our main analysis, we define early exposure to the Great Smog as having a first place of residence in London and being in utero or in the first year of life at the time of the smog.

Our health outcomes of interest are childhood and adulthood asthma. As part of the Life History survey, respondents were asked: “Did you have any of the health conditions on this card during your childhood (that is from when you were born up to and including age 15)”? and “Which conditions on this card, if any, accounted for of ill health or disability (that you had as an adult)”? For both questions, “Asthma” was one of the health conditions listed on the referenced card. Using these two questions, we code individuals as having “childhood asthma” or “adulthood asthma,” respectively.

Additional variables preselected for the analysis are sex and housing characteristics at age 10, the youngest available age. We included sex to account for differential asthma rates between genders and housing characteristics to proxy for childhood socioeconomic status (14, 15). Housing characteristics included are number of bedrooms; number of people living in the house; and specific facilities available within the accommodation, which include fixed bath, cold and hot running water, inside toilet, and central heating. Unfortunately, no information on exposure to other commonly cited risk factors for asthma, such as maternal asthma, respiratory syncytial virus infection, lower respiratory infection, or flu in infancy, are available before the reported development of asthma.

Analysis

We perform two complementary analyses to explore the relationship between early childhood exposure to the Great Smog and later onset of asthma. In our first analysis, we separately plot the rates of childhood and adult asthma by date of birth and place of residence using local polynomial regressions with Epanechnikov kernel weights (16). If pollution exposure during early childhood leads to later disease development, we expect to see higher rates of asthma in both childhood and adulthood for children residing in London at an early age during the Great Smog when compared with (1) children born outside of London, regardless of age, who were not exposed to the smog; (2) older children born within London, who did not experience early exposure to the smog; and (3) younger children born in London but conceived after the smog, who were also not exposed. All three comparisons are essential for interpreting our results as consistent with the long-lasting effects from early childhood exposure.

This research design accounts for several potential threats caused by confounding. For example, children born in London were more likely to experience asthma later in life for reasons other than exposure to the smog, because urban life in London posed many threats to the health of a child; this is captured by comparing early exposed London-born children with other London-born children who were born either after the smog or well before it. Additionally, if some change in health services or child rearing practices impacted all children across England around the time of the Great Smog, there is a danger of misattributing any resulting secular effects to the smog. The described analysis addresses this potential concern through the comparison of children living in London who were exposed to the smog with those of similar ages outside the city.

The second analysis supplements the graphical one with a multivariate regression analysis to provide estimates (and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) of the magnitude of the relationship between exposure and the development of asthma. In these models, we regress the outcomes of interest (childhood and adult asthma measured as binary variables) on whether the respondent was born in London, whether the respondent was in utero or age 0–1 during the time of the smog, and an interaction term between born in London and in utero or age 0–1 during the time of the smog. This regression analysis amounts to a difference-in-differences analysis (17). The first difference compares the asthma prevalence of children born within London at the time of the smog with the asthma prevalence of children born within London either greater than 1 year before or 9 months after the smog. The second difference performs the same comparison but for children born outside of London, which is then subtracted from the first difference to obtain the estimate of interest.

In addition to the variables described previously, we adjust these regressions for a quadratic term in year of birth (to account for flexible trends in asthma rates over time) and a series of month indicators (to account for the possibility of differential asthma rates by season of birth). In sensitivity analyses, we further adjust for the child’s sex and characteristics of their home at age 10.

We also augment this regression approach with an analysis that controls for year of birth more flexibly by replacing the quadratic terms with a series of indicator variables, which are then interacted with whether the respondent was born in London; this approach allows us to assess the differential effect from exposure to the smog at various ages. The Appendix E1 in the online supplement describes both regression analyses in more detail.

We use a linear probability model for the estimation throughout. Under the linear probability model the coefficient on the interaction term (age at the time of the Great Smog and place of birth) is the difference-in-differences estimate described previously (17), and should be interpreted as the percentage point change in the likelihood of developing asthma. Using a nonlinear model complicates the interpretation of such interaction terms (see Reference 18 for more details).2

To account for the group nature of exposure to the smog, SEs in all analyses are clustered at the year-month of birth level separately for those inside and outside of London (19). All analyses were conducted using STATA statistical software, version 14.1 (STATA Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

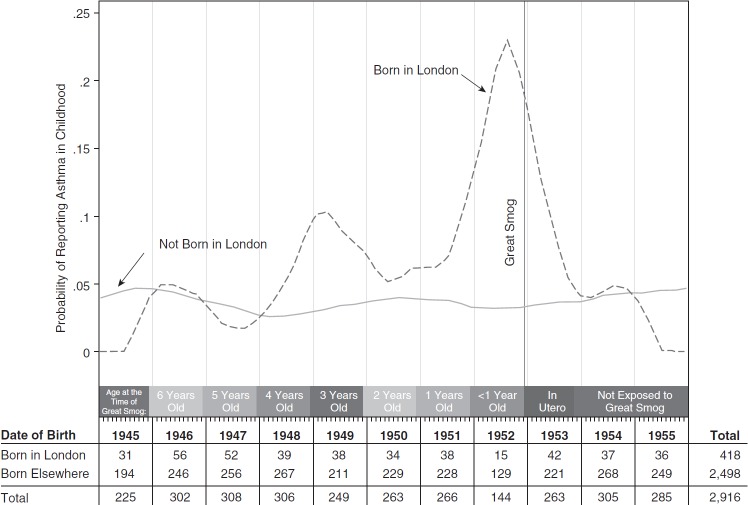

The table at the bottom of Figure 1 presents the number of survey respondents by place and year of birth. Note that the substantially smaller number of births in 1952 for both those born inside and outside of London is caused by the anomaly in the ELSA sampling procedure described previously. Table 1 summarizes covariates by respondent place of birth and age at the time of the Great Smog; characteristics of respondents are quite similar across place and date of birth. Table 2 summarizes the numbers of respondents that reported suffering from asthma during childhood and as adults. Asthma prevalences in our sample are 3.98% during childhood and 2.88% in adulthood, comparable with other estimates of asthma rates at the time (20).

Figure 1.

Asthma in childhood by date and location of birth. Plots report smoothed rates of childhood asthma by month of birth separately for those born inside and outside of London. Smoothing uses local polynomial regressions with Epanechnikov kernel weights.

Table 1.

Covariate Means by Relevant Group

| Born in London | Born Outside London | In Utero for Great Smog | Not In Utero for Great Smog | 0–1 Year Old for Great Smog | Not 0–1 Year Old for Great Smog | Full Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence at age 10 had | |||||||

| Bedrooms, n | 2.88 | 3.00 | 3.03 | 2.98 | 3.00 | 2.98 | 2.98 |

| Residents, n | 4.78 | 4.96 | 5.05 | 4.93 | 5.12 | 4.93 | 4.94 |

| Share that had |

|||||||

| Fixed bath | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| Cold running water | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| Hot running water | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.85 |

| Inside toilet | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| Central heating | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Individual characteristics | |||||||

| Proportion female | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.63 | 0.54 | 0.55 |

| Mean birth month | 6.38 | 6.40 | 5.88 | 6.44 | 6.02 | 6.42 | 6.40 |

| Respondents, n |

|||||||

| With all covariates | 407 | 2,412 | 194 | 2,625 | 147 | 2,672 | 2,819 |

| Total | 418 | 2,498 | 199 | 2,717 | 153 | 2,763 | 2,916 |

Sample includes respondents to the Life History survey of English Longitudinal Study on Aging who were born between 1945 and 1955, and for whom a location of first residence could be identified as being within or outside of London.

Table 2.

Rates of Self-reported Asthma during Childhood and Adulthood

| Adult Asthma |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Childhood asthma | |||

| No | 2,735 | 63 | 2,798 |

| Yes | 95 | 21 | 116 |

| Total | 2,830 | 84 | 2,914 |

Because of interviewer mistakes, one individual has data on childhood asthma but not adult, and one has data on adult asthma but not childhood. Thus, there are 2,916 respondents in our sample, with 2,914 individuals responding to both questions and 2,915 responding to each question.

Focusing first on childhood asthma, Figure 1 shows a relatively flat relationship between asthma and date of birth for children born outside London. For children born in London outside of the smog period, the prevalence of asthma is generally similar to those born outside of London throughout the study period. For children born in London around the time of the Great Smog, however, rates of reported asthma are considerably higher. Nearly 20% of children born in London around the time of the smog reported childhood asthma, whereas the rate never exceeds 11% among any other birth cohort. We also note that the spike in asthma rates for those born in 1949 could be a result of another smog incident that occurred in London during November 1948 (21).3

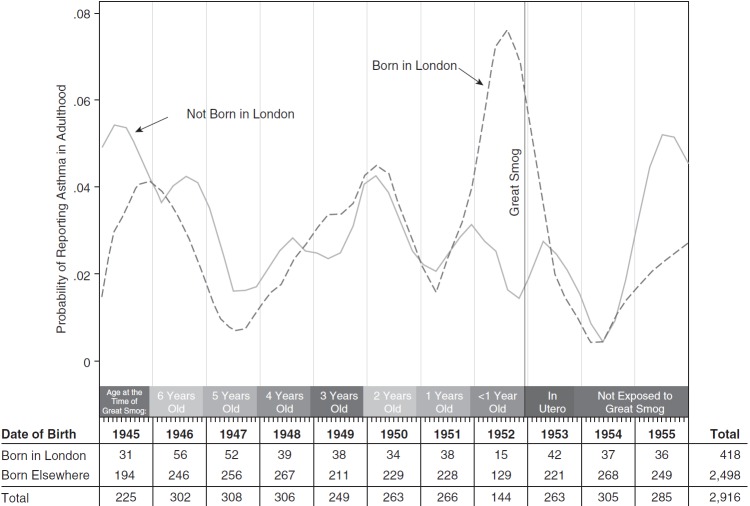

Figure 2 presents graphical evidence for adult asthma. Asthma rates in adulthood are generally lower and noisier, but a similar pattern emerges. Those born in London around the time of the smog have the highest rates of adult asthma, roughly double those of other cohorts. Otherwise, however, the rates of adult asthma between the two birth-location groups track one-another closely, highlighting the quality of the control group in this setting and suggesting that exposure to risk factors for adult asthma is more uniform within birth cohort than those for childhood asthma.

Figure 2.

Asthma in adulthood by date and location of birth. Plots report smoothed rates of adult asthma by month of birth separately for those born inside and outside of London. Smoothing uses local polynomial regressions with Epanechnikov kernel weights.

The multivariate regression results are presented in Table 3. Shown in column 1, those born in London who were 0–1 years old when the smog occurred have a 19.9 percentage point increased (95% CI, 3.37–36.38) likelihood of developing asthma during childhood relative to the comparison group of children born outside London and those who were not exposed to the Great Smog in utero or at age 0–1. Those in utero during the smog have a 7.9 percentage point increase (95% CI, −2.39 to 18.20) in childhood asthma, although it is not statistically significant. When we include additional controls (respondent sex and housing characteristics), shown in column 2, the estimates remain virtually unchanged.

Table 3.

Estimated Relationship between Early Exposure to Great Smog and Asthma Development

| Childhood Asthma |

Adult Asthma |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Covariate Adjusted (1) | Covariate Adjusted (2) | Not Covariate Adjusted (3) | Covariate Adjusted (4) | |

| 0–1 yr × born in London | 0.1987 (0.0337 to 0.364) | 0.1929 (0.0274 to 0.358) | 0.0953 (−0.0485 to 0.239) | 0.0934 (−0.0469 to 0.2340) |

| In utero × born in London | 0.0791 (−0.0239 to 0.182) | 0.0793 (−0.0233 to 0.182) | 0.0075 (−0.0534 to 0.0683) | 0.0055 (−0.0561 to 0.0671) |

| R2 | 0.0433 | 0.0788 | 0.013 | 0.041 |

| Observations | 2,915 | 2,743 | 2,915 | 2,740 |

95% confidence intervals in parentheses are calculated using SEs clustered by born in London status and month of birth. All regressions control for a quadratic term in year of birth, indicators for month of birth, indicators for in utero and 0–1 years old, and an indicator for born in London. Covariate-adjusted regressions include controls for respondent’s sex and housing characteristics at age 10 (number of bedrooms, number of people living in the house, cold running water, hot running water, inside toilet, central heat, and fixed bath). The first coefficient in column 1 reveals that exposure to the Great Smog between birth and age 1 (i.e., being born in London between December 1951 and November of 1952) is associated with a 19.87 percentage point increase in the likelihood of developing childhood asthma.

For adult asthma, the results in column 3 indicate that exposure to the Great Smog at age 0–1 is associated with a 9.5 percentage point increase (95% CI, −4.85 to 23.90) in the likelihood of the development of adult asthma compared with baseline levels, and a 0.75 percentage point increase (95% CI, −5.34 6.84) for those exposed in utero. Neither of these estimates, however, is statistically significant at conventional levels. The results in column 4, which include additional controls, are again very similar.

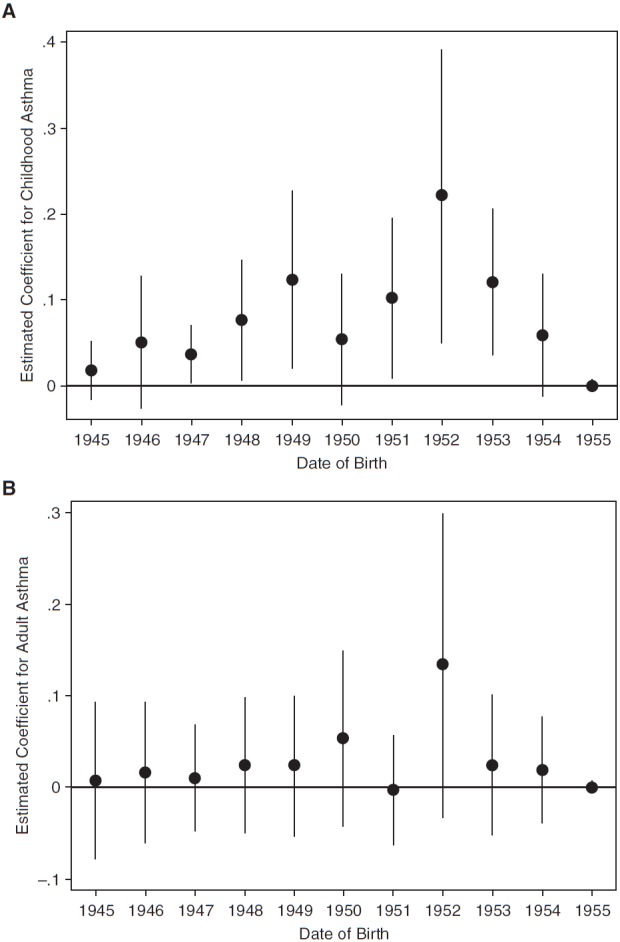

The results in the next set of figures more flexibly control for age at the time of exposure by interacting an indicator variable for each year of birth with whether each respondent was born in London. Figure 3A shows a statistically significant increase in the likelihood of childhood asthma for those born in 1952 (i.e., aged 0–1 at the time of the smog) and those born in 1953 (i.e., a similar group to those in utero at the time of the smog). Furthermore, the estimate for 1952 births is the largest of all groups, with the estimate for 1953 the third largest. These estimates are also quite comparable in magnitude with those obtained using the quadratic specification for year of birth.

Figure 3.

Coefficient estimates for childhood (A) and adult (B) asthma. Dots represent the regression-estimated coefficients on the interaction term between year of birth and whether the respondent was born in London. Regressions include controls for sex and age 10 residence characteristics. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals based on SEs clustered by born in London status and month of birth.

Focusing on adult asthma in Figure 3B, the difference in asthma rates is also highest for those born in 1952 (age 0–1 during the smog), although the estimate is not statistically significant (P = 0.111), likely caused by sample size and related statistical power issues. Again, the estimates for those born around the time of the Great Smog are comparable with those in Figure 1 and those using the quadratic in year of birth (presented in Table 3).

Discussion

This study presents the first evidence of long-lasting effects from early childhood exposure to the Great Smog of 1952, focusing on the development of asthma through childhood and in adulthood. Using nonparametric plots of the raw data and multivariate regression analysis, we demonstrate that children born in London around the time of the Great Smog experienced dramatically higher rates of self-reported asthma during childhood. Although we do not find statistically significant effects for adult asthma, we generally find similar patterns of results for childhood and adult asthma in that they both peak among those in utero and ages 0–1.4

Although we cannot address the exact mechanism behind this finding, the most consistent explanation rests with the “fetal origins hypothesis” (7). Rapid biologic development occurs during the early childhood period (23), which is particularly sensitive to external stimuli (24, 25). Exposure to such stimuli can lead to permanent changes in human development, and disease states as an adult (26). For example, exposure to harmful stimuli can lead to epigenetic changes through DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNA expression, thereby affecting a human’s genetic expression and susceptibility to disease (27). Asthma is one such disease with presumed fetal origins (28).

Air pollution is an external stimulus that may affect fetal programming, including genetic expression. For example, DNA methylation of the FOXP3 gene affects the population of regulatory T cells, which are an essential driver of chronic asthma (29). Exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) has been associated with hypermethylation of the FOXP3 gene (30). Although the precise pollutant mix during the 1952 episode is unknown, PM2.5, which was found in postmortem examinations of lung tissues among those exposed to the London Smog, was certainly present (21).

A growing body of empirical evidence using historical events suggests that early exposure to negative stressors affects various outcomes later in life (8, 31, 32), with an emerging focus on air pollution in particular (33–35). The literature that directly explores the relationship between early childhood exposure to pollution and asthma development is also growing rapidly, but remains strictly correlational in nature (14, 36–41) and hence can do little to rule out the potential threats from confounding that have historically proven important in pollution-related studies. Our approach, by relying on the grand experiment of the Great Smog, overcomes many potential confounding threats (42), and suggests a strong possibility of a causal link between early childhood exposure to air pollution and the later development of asthma.

One potential limitation of our analysis concerns measurement error related to our definitions of asthma and exposure. The asthma data are self-reported, which may result in misclassification caused by recall bias. However, because recall bias is unlikely to differ across exposed and comparison groups, it is unlikely to bias our results. Moreover, the rates of childhood asthma observed in our study closely reflect those from a survey and doctor examination of primary school students in Aberdeen, United Kingdom in 1964 (43, 44), suggesting that recall issues are minimal.

Another measurement issue is our demarcation of those within the geographic bounds of the Great Smog. Our definition of London includes the area now bounded by the M25 Ring Road. If the smog were concentrated in the inner boroughs of London, we could be misclassifying the extent of exposure by including the outer boroughs. When we restrict our analysis to include only the inner boroughs (and omit those in the outer boroughs), our estimates change minimally. Conversely, because inversions tend to cover large areas, it might be the case that we are classifying too small an area as affected by the smog. To the extent that poor air quality affected areas outside of London, the magnitude of our estimated effects would be biased downward and thus understate the harmful effects of the Great Smog. Finally, misreporting of a respondent’s first place of residence, although not possible to detect, would again lead to downward bias in our estimates (45).

Although confounding is always a potential concern in nonexperimental settings, this concern is greatly limited in our analysis. The Great Smog was an unexpected, short-lived event caused by a temperature inversion and windless conditions (4).5 Combining these features with the use of multiple comparison groups helps us to rule out alternative explanations for the later rise in asthma. The results we find are unlikely to be an artifact from living in an urban area because our estimate is the change in differences between asthma among those born in London and others. Thus, the higher average prevalence of asthma among urban children is removed from consideration in our estimates. Similarly, our findings cannot be attributed to other commonly cited risk factors for the development of asthma unless the prevalence of these factors changed differentially within versus outside of London only during the Great Smog event. It is also unlikely that the pattern we find is caused by temporal or seasonal trends because asthma rates only spike for the exposed cohorts. Finally, our estimates do not seem to be the result of nationwide circumstances that coincided with the timing of the smog because we do not see a spike in asthma rates among non-London-born children at the time of the smog.

The only alternative explanation that could generate the pattern of results uncovered by our analysis is the occurrence of another event that occurred only in London at the same time as the Great Smog and had latent health effects only among children that were very young at the time. We are unaware of any other such event.

Rather, the dramatic spike in asthma rates only among those exposed at the most vulnerable ages suggests that early childhood exposure to high levels of pollution contributed to the development of asthma later in life. Thus, the legacy of the Great Smog lives on in England today, more than a half century on. The implications of our results are quite broad, raising concerns about sizeable health burdens from present-day air pollution that stretch far into the future. Although the mix of pollutants during the Great Smog may differ from the mix in major pollution events today, parallels have been drawn to recent events in such places as Beijing and Northeastern China (49, 50). Going forward, the continued use of natural experiments with better surveillance of relevant outcomes, through surveys or administrative records, and improved measurement of environmental exposure in utero and in early childhood will further validate this study.

Footnotes

The term “smog” refers to a mix of pollutants (smoke) and environmental factors (fog).

A concern with linear probability models is the possibility of predicted probabilities outside of 0 and 1. Appendix E2 presents the results of an analysis based on a logistic regression framework and further discussion regarding the comparison of linear probability models and logistic models.

Other significant smog events occurred in London during November 1948, January 1956, December 1957, January 1959, and December 1962, although the levels of pollution and mortality associated with these incidents were generally much lower than those associated with the Great Smog (2, 21).

Some differences in the childhood and adult results clearly exist and may be attributable to the different etiology of adult asthma (22). Figure 2 also suggests the adult asthma rates are much noisier, indicating a potential role for background factors.

Several other studies have used inversion layers to study the contemporaneous effects of air pollution on health (46–48).

Supported by a grant from the University of California Center for Energy and Environmental Economics.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design, P.B. and J.G.Z. Acquisition of data, J.G.Z. and J.T.M. Analysis and interpretation of data, P.B., J.T.M., and M.N. Drafting of the manuscript, M.N. and J.T.M. Critical revision of the manuscript, all authors. Statistical analysis, P.B. and J.T.M.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0451OC on July 8, 2016

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Logan WP. Mortality in the London fog incident, 1952. Lancet. 1953;1:336–338. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(53)91012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell ML, Davis DL, Fletcher T. A retrospective assessment of mortality from the London smog episode of 1952: the role of influenza and pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:6–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell ML, Davis DL. Reassessment of the lethal London fog of 1952: novel indicators of acute and chronic consequences of acute exposure to air pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:389–394. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greater London Authority. 50 years on: the struggle for air quality in London since the Great Smog of December 1952. London: Greater London Authority; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snow J. On the mode of communication of cholera. London: John Churchill; 1855. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freedman DA. Statistical models and shoe leather. Sociol Methodol. 1991;21:291–313. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker DJP. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ. 1990;301:1111. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6761.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almond D, Currie J. Killing me softly: the fetal origins hypothesis. J Econ Perspect. 2011;25:153–172. doi: 10.1257/jep.25.3.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Mutius E. The environmental predictors of allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lemanske RF, Jr, Busse WW. 6. Asthma: Factors underlying inception, exacerbation, and disease progression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(Suppl Mini-Primer):S456–S461. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beasley R, Semprini A, Mitchell EA. Risk factors for asthma: is prevention possible? Lancet. 2015;386:1075–1085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marmot M, Oldfield Z, Clemens S, Blake M, Phelps A, Nazroo J, Steptoe A, Rogers N, Banks J.English Longitudinal Study of Ageing: Waves 0-5, 1998-2011 [computer file]20th editionUK Data Archive [distributor]2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scholes S, Taylor R, Cheshire H, Cox K, Lessof C. Living in the 21st century: older people in England, the 2006 English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, technical report. London: National Centre for Social Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu HH, Chiu YH, Coull BA, Kloog I, Schwartz J, Lee A, Wright RO, Wright RJ. Prenatal particulate air pollution and asthma onset in urban children: identifying sensitive windows and sex differences. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:1052–1059. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0658OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shankardass K, McConnell R, Jerrett M, Milam J, Richardson J, Berhane K. Parental stress increases the effect of traffic-related air pollution on childhood asthma incidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12406–12411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812910106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fan J, Gijbels I. Local polynomial modelling and its applications: monographs on statistics and applied probability 66. Vol. 66. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wooldridge JM. Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ai C, Norton EC. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Econ Lett. 2003;80:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moulton BR. Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates. J Econom. 1986;32:385–397. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sunyer J, Antó JM, Tobias A, Burney P European Community Respiratory Health Study (ECRHS) Generational increase of self-reported first attack of asthma in fifteen industrialized countries. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:885–891. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d26.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt A, Abraham JL, Judson B, Berry CL. Toxicologic and epidemiologic clues from the characterization of the 1952 London smog fine particulate matter in archival autopsy lung tissues. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1209–1214. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Nijs SB, Venekamp LN, Bel EH. Adult-onset asthma: is it really different? Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22:44–52. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thurlbeck WM. Postnatal growth and development of the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975;111:803–844. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1975.111.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gauderman WJ, McConnell R, Gilliland F, London S, Thomas D, Avol E, Vora H, Berhane K, Rappaport EB, Lurmann F, et al. Association between air pollution and lung function growth in southern California children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1383–1390. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9909096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gern JE, Rosenthal LA, Sorkness RL, Lemanske RF., Jr Effects of viral respiratory infections on lung development and childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:668–674, quiz 675. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:61–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chuang JC, Jones PA. Epigenetics and microRNAs. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:24R–29R. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180457684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner S. Perinatal programming of childhood asthma: early fetal size, growth trajectory during infancy, and childhood asthma outcomes. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:962923. doi: 10.1155/2012/962923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kon OM, Kay AB. Anti-T cell strategies in asthma. Inflamm Res. 1999;48:516–523. doi: 10.1007/s000110050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadeau K, McDonald-Hyman C, Noth EM, Pratt B, Hammond SK, Balmes J, Tager I. Ambient air pollution impairs regulatory T-cell function in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:845–852.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein Z, Susser M, Saenger G, Marolla F. Famine and human development: the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944-1945. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almond D. Is the 1918 influenza pandemic over? Long-term effects of in utero influenza exposure in the post-1940 US population. J Polit Econ. 2006;114:672. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bharadwaj P, Gibson M, Zivin JG, Neilson CA.Gray matters: fetal pollution exposure and human capital formation J Assoc Environ Resour EconIn press) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Isen A, Rossin-Slater M, Walker WR.Every breath you take-every dollar you’ll make: the long-term consequences of the Clean Air Act of 1970 J Polit EconIn press) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders NJ. What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker: prenatal pollution exposure and educational outcomes. J Hum Resour. 2012;47:826–850. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nishimura KK, Galanter JM, Roth LA, Oh SS, Thakur N, Nguyen EA, Thyne S, Farber HJ, Serebrisky D, Kumar R, et al. Early-life air pollution and asthma risk in minority children: the GALA II and SAGE II studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:309–318. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0264OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunst KJ, Ryan PH, Brokamp C, Bernstein D, Reponen T, Lockey J, Khurana Hershey GK, Levin L, Grinshpun SA, LeMasters G. Timing and duration of traffic-related air pollution exposure and the risk for childhood wheeze and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:421–427. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1314OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gehring U, Wijga AH, Hoek G, Bellander T, Berdel D, Brüske I, Fuertes E, Gruzieva O, Heinrich J, Hoffmann B, et al. Exposure to air pollution and development of asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis throughout childhood and adolescence: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:933–942. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brauer M, Hoek G, Smit HA, de Jongste JC, Gerritsen J, Postma DS, Kerkhof M, Brunekreef B. Air pollution and development of asthma, allergy and infections in a birth cohort. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:879–888. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00083406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark NA, Demers PA, Karr CJ, Koehoorn M, Lencar C, Tamburic L, Brauer M. Effect of early life exposure to air pollution on development of childhood asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:284–290. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0900916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gruzieva O, Bergström A, Hulchiy O, Kull I, Lind T, Melén E, Moskalenko V, Pershagen G, Bellander T. Exposure to air pollution from traffic and childhood asthma until 12 years of age. Epidemiology. 2013;24:54–61. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318276c1ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dominici F, Greenstone M, Sunstein CR. Science and regulation. Particulate matter matters. Science. 2014;344:257–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1247348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dawson B, Illsley R, Horobin G, Mitchell R. A survey of childhood asthma in Aberdeen. Lancet. 1969;1:827–830. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ninan TK, Russell G. Respiratory symptoms and atopy in Aberdeen schoolchildren: evidence from two surveys 25 years apart. BMJ. 1992;304:873–875. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6831.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aigner DJ. Regression with a binary independent variable subject to errors of observation. J Econom. 1973;1:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arceo E, Hanna R, Oliva P. Does the effect of pollution on infant mortality differ between developing and developed countries? Evidence from Mexico City. Econ J. 2016;126:257–280. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pope CA, III, Schwartz J, Ransom MR. Daily mortality and PM10 pollution in Utah Valley. Arch Environ Health. 1992;47:211–217. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1992.9938351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wichmann HE, Mueller W, Allhoff P, Beckmann M, Bocter N, Csicsaky MJ, Jung M, Molik B, Schoeneberg G. Health effects during a smog episode in West Germany in 1985. Environ Health Perspect. 1989;79:89–99. doi: 10.1289/ehp.897989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dockery DW, Pope CA.Lost life expectancy due to air pollution in China Risk Dialogue Magazine 2014175–11.. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang D, Liu J, Li B. Tackling air pollution in China: what do we learn from the Great Smog of 1950s in London. Sustainability. 2014;6:5322–5338. [Google Scholar]