Abstract

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) due to Brucella spp. is rare. We report a case in a 75-year-old man and review 29 additional cases identified in a literature search. The diagnosis of Brucella PJI is challenging, in particular in non-endemic countries. Serological tests prior to joint aspiration or surgical intervention are reasonable. Involvement of infection control and timely information to laboratory personnel is mandatory upon diagnosis. There is no uniform treatment concept, neither with respect to surgical intervention nor for the duration of antimicrobials. Most cases have a successful outcome, irrespective of surgical modality, and with an antimicrobial combination regimen for 12 or more weeks.

Keywords: Brucella, Periprosthetic joint infection

Intraduction

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) due to Brucella is rare. We present a case of PJI due to Brucella melitensis and review the literature with respect to clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment.

Case Report

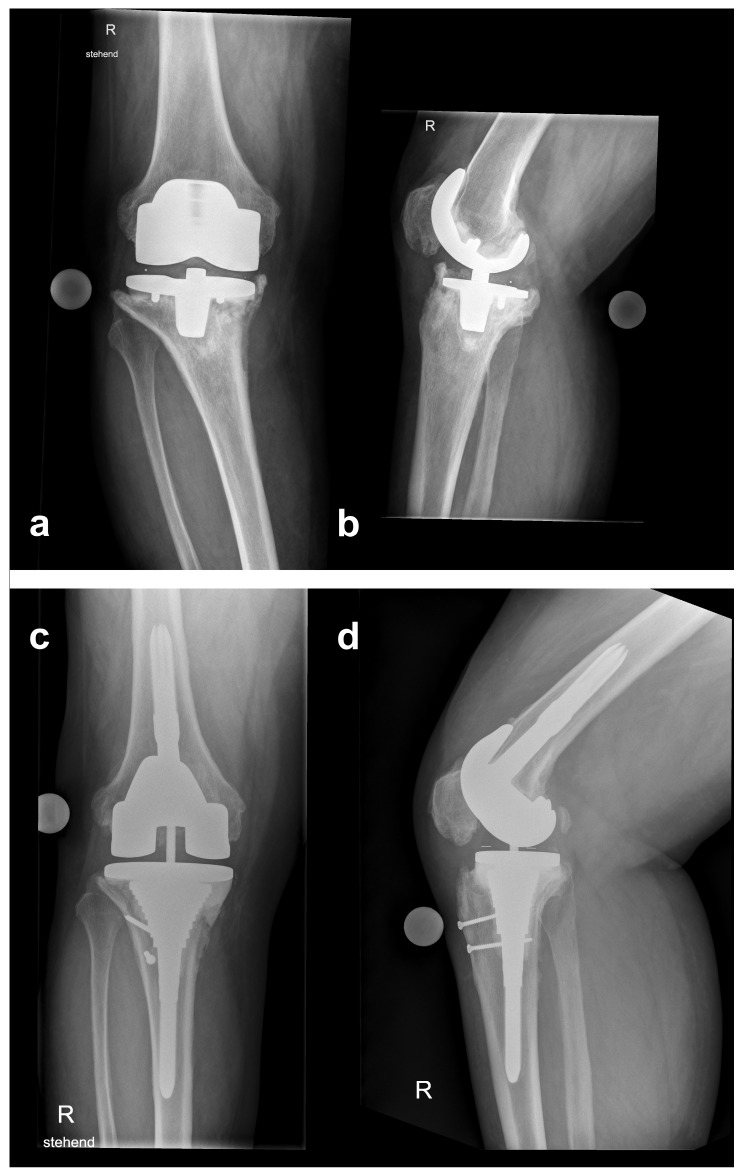

A 75-year-old man from Turkey presented with a six-months history of progressing knee pain. His personal history included total right knee arthroplasty (TKA) because of osteoarthritis 12 years prior to, and one stage exchange due to aseptic loosening 4 years prior to admission. On presentation, radiographs of the right knee showed loosening of the prosthesis with migration of the tibial component (Figure 1a, b). Before referral to our center, B. melitensis grew in synovial fluid specimen obtained via arthrocentesis.

Figure 1.

Initial anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs at referral showing a loose and displaced femoral and tibial component. Anteroposterior (c) and lateral (d) radiographs at follow-up 2 years after reimplantation.

The patient was born and raised in Turkey: He had moved to Switzerland at the age of 44. He reported to spend his summers in Turkey. There, he owns a house in a rural area, and commonly ingests fresh unpasteurized cheese and milk.

On presentation, he was afebrile and no episodes of fever or night sweats were reported. Blood tests showed a C-reactive protein (CRP) of 18 mg/l (norm < 8 mg/l); leukocytes and thrombocytes were within normal range. Chest and lumbar radiographs, as well as abdominal ultrasound, were normal. Two sets of blood cultures remained negative. Serological test for antibodies against Brucella spp. were positive (IgG/IgA of 1:240 U/mL, normal < 20 U/ml; Brucella IgG/M/A Serion ELISA classic, SERION® Immunologics, Wuerzburg, Germany).

A combined antimicrobial therapy consisting of doxycycline 100 mg twice per day and intravenous (IV) gentamicin 5 mg/kg once daily was started one week prior to surgery. The surgical plan included a two-stage exchange with a short interval. After removal of the implant, a mobile antibiotic loaded spacer (containing gentamicin and vancomycin) was implanted. Surgery was carried out under aerosol isolation precautions and laboratory personnel were informed about possible risk of exposure. B. melitensis grew in 3, and Propionibacterium acnes in 4 out of 10 obtained biopsies, sonication was negative. Thus, penicillin was added to the regimen (24 million units IV divided in 6 doses per day). After 2.5 weeks, a revision TKA was implanted (LCS Revision®, DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, IN). The further clinical course was uneventful. In the postoperative period, treatment with rifampin 450 mg twice per day was added, and gentamicin discontinued. Because P. acnes proved to be susceptible to doxycycline, treatment with penicillin was stopped and continued with doxycycline plus rifampin. Three months after surgery, monotherapy with doxycycline for another three months was prescribed.

At the 2-year follow-up examination, the patient reported good joint function (ROM 0/5/105, WOMAC-Scale 12, VAS 80, EQ-5D 1) without clinical signs of infection. Radiographs showed a properly aligned TKA and no signs of loosening (Figure 1cd).

Review of the Literature

Methods

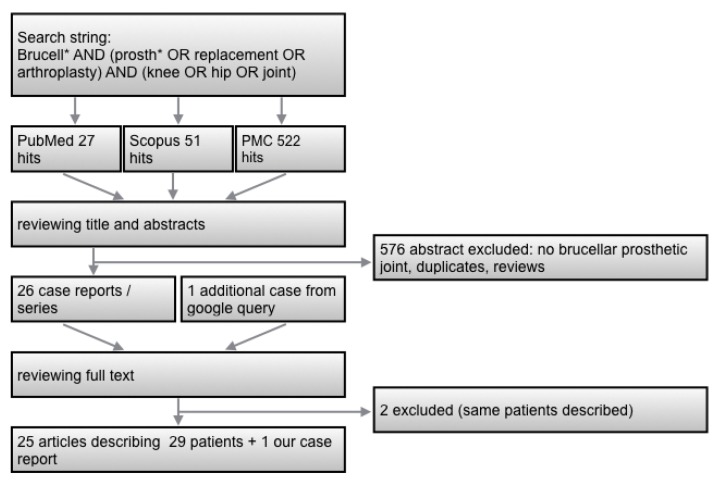

For identifying published case reports, PubMed, PMC and Scopus databases were searched using the search string “Brucell* AND (prosth* OR replacement OR arthroplasty) AND (knee OR hip OR joint)”. Further a google query for “Brucella PJI” was performed. No restriction for time period of publications was applied. Two authors (DF and CS) reviewed titles and abstracts without restriction on date or language. Cases with symptoms consistent with PJI and Brucella spp. recovered from either synovial fluid culture or biopsy samples were included.

Results

The literature screening procedure is illustrated in Figure 2. Twenty-five published articles describing 29 patients were identified 1-25 (Table 1). Three of them were co-infections. Two articles describing the same patients were excluded 26, 27.

Figure 2.

Flow-chart for literature research.

Table 1.

Demographics and diagnostics

| Patient No | Demographics | Country of Exposure |

Involved Prosthesis |

Age of PJ (months) |

Previous Revisions |

Symptoms | Cultures | Brucella | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age & sex | Exposure risk | Species | Aspiration | Tissue | Blood Culture | Co-infection | Serologies* | |||||||

| 1 | 24, f | na | Saudi Arabia | TKR bilateral | 2 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | pos | na | na | no | pos | 1 |

| 2 | 72, m | unpasteurized dairy products | Turkey | TKR | 48 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | na | pos | neg | no | pos | 2 (27) |

| 3 | 50, m | farmer, cattle | Spain | THR | 0 | no | systemic and local | B. melitensis | na | pos | pos | no | pos | 3 |

| 4 | 71, m | farmer, cattle | Spain | THR | 36 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | na | pos | na | yes | na | 3 |

| 5 | 67, f | na | Mexico | THR | 24 | no | local symptoms | B. abortus | neg | pos | na | no | na | 4 (26) |

| 6 | 65, f | unpasteurized dairy products | Portugal | TKR bilateral | na | no | systemic and local | B. melitensis | neg | pos | na | no | na | 5 |

| 7 | 63, f | unpasteurized dairy products | Turkey | TKR | 24 | yes | systemic and local | B. melitensis | neg | pos | neg | no | pos | 6 |

| 8 | 71, f | na | Spain | TKR | 48 | no | systemic and local | Brucella sp | pos | na | na | no | pos | 7 |

| 9 | 68, f | na | Iran | TKR | 12 | no | local symptoms | Brucella sp | neg | pos | na | no | na | 8 |

| 10 | 54, m | farmer | United States | THR | 6 | no | systemic and local | B. abortus | neg | pos | na | no | pos | 9 |

| 11 | 62, m | na | Turkey | TKR | 24 | no | systemic and local | B. melitensis | pos | na | na | no | pos | 10 |

| 12 | 47, m | unpasteurized dairy products | Lebanon | THR | 168 | no | local symptoms | Brucella sp | na | pos | na | no | pos | 11 |

| 13 | 79, m | contact with cattle | Israel/ Argentina | TKR | 144 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | na | pos | na | no | na | 12 |

| 14 | 51, m | contact with goats | Thailand | TKR | 60 | no | systemic and local | B. melitensis | pos | na | pos | no | pos | 13 |

| 15 | na | unpasteurized dairy products | India | THR | na | na | na | B. melitensis | pos | na | na | na | na | 14 |

| 16 | 74, m | shepherd | Greece | TKR bilateral | 4 | no | systemic and local | B. melitensis | pos | na | pos | no | pos | 15 |

| 17 | 67, f | unpasteurized dairy products | Italy | TKR bilateral | 48 | no | local symptoms | Brucella sp | neg | pos | na | no | na | 16 |

| 18 | 74, m | unpasteurized dairy products | Italy | TKR | 108 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | na | pos | na | no | pos | 17 |

| 19 | 65, f | na | Turkey | TKR bilateral | 96 | no | systemic and local | B. melitensis | pos | na | na | no | pos | 18 |

| 20 | 63, m | contact with cattle | Spain | THR | 60 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | pos | pos | neg | no | na | 19 |

| 21 | 60, m | contact with goats | Spain | TKR | 14 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | pos | na | neg | no | pos | 20 |

| 22 | 66, f | contact with cattle | Spain | THR | 36 | no | local symptoms | B. abortus | pos | na | na | no | na | 21 |

| 23 | 71, m | farmer, cattle | Spain | THR | 63 | yes | local symptoms | B. melitensis | na | pos | na | no | pos | 21 |

| 24 | 68, m | na | Italy | TKR | 24 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | pos | na | na | no | pos | 22 |

| 25 | 56, m | farmer, sheep | Spain | THR | 60 | no | systemic and local | B. melitensis | pos | na | neg | no | pos | 23 |

| 26 | 38, m | unpasteurized dairy products | Israel | THR | 48 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | neg | pos | na | no | pos | 24 |

| 27 | 61, m | unpasteurized dairy products | Israel | TKR | 36 | yes | local symptoms | B. melitensis | pos | pos | na | yes | pos | 24 |

| 28 | 67, m | unpasteurized dairy products | Israel | TKR | 168 | no | systemic and local | B. melitensis | pos | na | na | no | pos | 24 |

| 29 | 64, f | unpasteurized dairy products | Turkey | TKR | 60 | no | local symptoms | B. melitensis | pos | na | na | no | pos | 25 |

| 30 | 75, m | unpasteurized dairy products | Turkey | TKR | 144 | yes | local symptoms | B. melitensis | pos | pos | neg | yes | pos | this case |

* Serum agglutination (=standard tube agglutination (SAT)) was used in most cases. Only positive results were quoted because of limited comparability among the different tests used; THR total hip replacement; TKR total knee replacement; PJ prosthetic joint; na not available.

Most patients were male and originated from southern Europe (Spain, Portugal, Italy, Portugal, Greece), or the Middle East (Turkey, Israel, Lebanon, Iran, Saudi Arabia). The majority reported a history that was congruent with the pathogenesis (e.g., regular consumption of unpasteurized dairy products, occupational exposure to animals).

Eleven hip and 19 knee infections were described. The range of time interval between implantation of the prosthesis and the diagnosis of PJI was very broad (from immediately postoperative up to 168 months) with a median of 48 months. 62% (18/29) of patients had only local symptoms, and 38% (11/29) both systemic (mainly fever, malaise) and local symptoms. More than half of the patients (17/29) had a radiologically documented loosening of the implant. Twenty-three cases of B. melitensis, three of B. abortus and four cases of Brucella sp. were described. Diagnosis was mostly made by positive joint aspiration cultures (16/23). When no aspiration was performed (7/30) or aspiration culture was negative (7/23) intraoperative tissue biopsies were diagnostic. Only three cases had reported positive blood cultures. All cases with reported serology results revealed positive anti-Brucella antibodies (21/21). Three co-infections were documented, our case with P. acnes, one with viridans-group streptococci and one with Acinetobacter baumanii. In patients with radiological documented loosening, a one-stage exchange was performed in three, removal of the implant without replacement in one, and a two-stage exchange with a long interval (between 6 weeks and 6 months, median 8 weeks) in 12 cases. In twelve patients without implant loosening, eight patients were treated conservatively (i.e. without surgery), two had a debridement with retention of the prosthesis and one had a one-stage and two-stage exchange, respectively. The outcome of all patients was reported as good. However, a follow up of a year or more was reported in only 23/30 cases (maximal 10 years, median 2 years). Moreover, we cannot exclude a publication bias (i.e., only cases with a good outcome are reported). The antimicrobial regimen consisted of doxycycline and rifampin in most cases, with or without an aminoglycoside (streptomycin or gentamicin). In single cases quinolones or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were used as a salvage treatment. The duration of antibiotic therapy varied markedly (median 16 weeks, range 6 weeks to 2 years) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment and follow-up.

| Patient No | Implant Loosening |

Surgical Treatment |

Implant-free Interval (weeks) |

Antimicrobial Treatment and Duration (weeks) |

Good outcome |

Follow-up (years) |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | no | none | Dox/Rif 76w | yes | 1.5 | 1 | |

| 2 | no | DAIR (arthroscopy) | Dox/Rif 6wk | yes | 1 | 2 (27) | |

| 3 | no | none | Strep(2w)/Dox 106w | yes | 5 | 3 | |

| 4 | yes | one-stage exchange | Strep(1.5w)/Doxy/Rifa 25.5 w | yes | 3 | 3 | |

| 5 | yes | two-stage exchange | 24 | Dox/Rif 20w | yes | 2 | 4 (26) |

| 6 | yes | two-stage exchange | 6 | Dox/Rif 12 w | yes | 10 | 5 |

| 7 | no | none | Dox/Rif 16w | yes | 3 | 6 | |

| 8 | no | none | Dox/Rif 6.5w; then Strep(3w)/Dox 12w | yes | <1 | 7 | |

| 9 | no | two-stage exchange | 24 | na | na | na | 8 |

| 10 | no | one-stage exchange | Tet 6w, then Tet 24w, then Strep(6w)/Tet 58w | yes | 2 | 9 | |

| 11 | yes | two-stage exchange | 12 | Dox/Rif 12w | yes | 10 | 10 |

| 12 | yes | one-stage exchange | Dox/Rif 20w | yes | 4 | 11 | |

| 13 | yes | two-stage exchange | 8 | Gen(3w)/Dox/Rif 25w, then Dox/Rif/Bact >52w | yes | <1 | 12 |

| 14 | no | none | Gen(2w)/Dox/Rif 24w | yes | 1 | 13 | |

| 15 | na | na | na | na | na | 14 | |

| 16 | no | none | Strep(3w)/Dox 20w, then Bact 8w | yes | 2 | 15 | |

| 17 | yes | two-stage exchange | 12 | Dox/Rif 12 w | yes | 1.5 | 16 |

| 18 | yes | Implant removal | Strep/Dox 4w, then Dox/Rif/Levo 32w | yes | < 1 | 17 | |

| 19 | yes | two-stage exchange | 20 | Dox/Rif 16w | yes | 2 | 18 |

| 20 | yes | two-stage exchange | 16 | Strep/Dox/Rif 12w | yes | <1 | 19 |

| 21 | no | none | Strep/Dox/Rif 6w | yes | <1 | 20 | |

| 22 | yes | two-stage exchange | 16 | Dox/Rif 6w | yes | 5.5 | 21 |

| 23 | no | DAIR | Strep(6w)/Dox/Rif 24w | yes | 5 | 21 | |

| 24 | no | none | Dox/Rif 8w | yes | 1 | 22 | |

| 25 | yes | two-stage exchange | 8 | Strep(2w)/Dox/Rif 8w | yes | 4 | 23 |

| 26 | yes | two-stage exchange | 6 | Dox/Rif 12 w | yes | 1 | 24 |

| 27 | yes | two-stage exchange | 6 | Dox/Rif 12 w | yes | 1 | 24 |

| 28 | yes | two-stage exchange | 6 | Dox/Rif 12 w | yes | 1 | 24 |

| 29 | yes | one-stage exchange | Dox/Rif 24 w | yes | 1.5 | 25 | |

| 30 | yes | two-stage exchange | 2.5 | Dox/Rif/Pen 24w | yes | 2 | this case |

Strep: Streptomycin; Gen: Gentamicin; Dox: Doxycycline; Rif: Rifampin; Bact: Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole; Levo: Levofloxacin; Tet: Tetracycline; Pen: Penicillin G; DAIR: debridement, antibiotics, irrigation and retention.

Discussion

The preoperative diagnosis of Brucella PJI is a challenge in non-endemic countries, mainly because of the rarity of the disease, and hence, lack of clinical experience. The microbiological analyses of synovial fluid in patients with suspected PJI is part of the routine diagnostic procedure in many centers. In case of Brucella PJI, however, this intervention - without the required aerosol precautions - may expose personnel both in the operating room and microbiology laboratory to the pathogen 28. In contrast, serological tests for brucellosis in previously untreated patients and in non-endemic region are reliable and safe diagnostic tools 29. Our and all reported cases revealed significant elevated anti-Brucella-antibodies. Thus, it is conceivable to think of brucellosis and perform serological tests prior to synovial puncture, when the patient history (e.g., exposure to unpasteurized dietary products) or his ethnicity points towards this differential diagnosis.

In cases of suspected or confirmed Brucella PJI, infection control precautions are necessary prior to a surgical intervention. Laboratory staff must be pre-informed about potential growth of Brucella spp. when biopsy samples are sent for analyses 14, 28, 30. Our literature review indicates that cultures of intra-operative tissue samples provide the best yield.

There is no uniform recommendation for the surgical procedure in Brucella PJI. Loose implants must be exchanged, and successful outcomes with both one-stage and two-exchanges have been reported. Although a wide range of time periods for the implant-free interval have been reported (i.e., 6 weeks to 6 months), we were unable to find a scientific rational against a short interval. Although, Brucella spp. have shown to form Biofilm in vitro 31, 32, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on Brucella-associated biofilm production on orthopedic implants. Thus, the clinical significance of in-vitro results requires further investigations. The overall good prognosis of Brucella PJI irrespective of applied treatment concept supported our surgical concept of a short interval.

Antimicrobial treatment for brucellosis requires a combination regimen, because high relapse rates have been reported with monotherapy. Rifampin, doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and aminoglycosides have good activity against brucellosis. Antimicrobial drug resistance is unusual but can be determined by the Etest method 33. Doxycycline plus streptomycin or doxycycline plus rifampin are the most commonly-used combinations 34-36. Given the side effects of aminoglycosides, in particular in the elderly, we prefer not to use gentamicin or streptomycin for a prolonged treatment period.

It may be reasonable to start antimicrobial treatment prior to surgical intervention to lower the bacterial load, provided that Brucella spp. and other microorganisms are isolated from a preoperative joint puncture. In 10% of the described cases, a polymicrobial infection was reported. In retrospect, P. acnes may have been missed in our case.

The optimal treatment duration in Brucella PJI is unknown. In brucellosis, irrespective of infection site, less than 6 weeks with monotherapy is associated with failure 37. In analogy to treatment recommendation for brucellar spondylitis, we targeted a combination therapy of at least 12 weeks 35.

Conclusions

Brucella PJI is rare, and the diagnosis is often unexpected in non-endemic countries. Thinking of risk factors and ethnicity is the key to the diagnosis. Serological tests should be performed prior to joint puncture or surgical interventions. In case of positive anti-Brucella-antibodies, infection control must be involved and laboratory personnel informed prior to obtaining samples. Our review of the literature indicates that the prognosis is good, irrespective of surgical treatment modality. In rare cases, a polymicrobial infection can occur. On the basis of these data, and with respect to a shorter hospitalization period and better joint function, we prefer either a one-stage exchange or a two-stage exchange with a short interval in case of loose implants. A combination antimicrobial regimen is recommended, though, the optimal treatment duration is unknown. In our case, a 3-month course of doxycycline plus rifampin, followed by a 3 month-course of doxycycline monotherapy showed a successful outcome.

References

- 1.Agarwal S, Kadhi SK, Rooney RJ. Brucellosis complicating bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res; 1991. pp. 179–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atay T, Baydar ML, Heybeli N. [Brucellar Prosthetic Infection After Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Case With Retained Prosthesis by Arthroscopic and Medical Treatment] Trakya Univ Tip Fak Derg. 2008;25:252–255. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cairo M, Calbo E, Gomez L, Matamala A, Asuncion J, Cuchi E. et al. Foreign-body osteoarticular infection by Brucella melitensis: A report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:202–4. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carothers JT, Nichols MC, Thompson DL. Failure of total hip arthroplasty secondary to infection caused by Brucella abortus and the risk of transmission to operative staff. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44:E42–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dauty M, Dubois C, Coisy M. Bilateral knee arthroplasty infection due to Brucella melitensis: a rare pathology? Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:215–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erdogan H, Cakmak G, Erdogan A, Arslan H. Brucella melitensis infection in total knee arthroplasty: a case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:908–10. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iglesias G, Arboleya L, Arranz J. [Brucellar arthritis in a knee with prosthesis] Revista Española de Reumatología. 1997;24:32–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabalameli M, Bagherifard A, Hadi H, Qomashi I. Infected Total Knee Arthroplasty by Brucella melitensis: A Rare Case Report. Shafa Orthopedic Journal. 2016 In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones RE, Berryhill WH, Smith J, Hofmann A, Rogers D. Secondary infection of a total hip replacement with Brucella abortus. Orthopedics. 1983;6:184–6. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19830201-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karaaslan F, Mermerkaya M, Karaoğlu S, Ayvaz M. Total Knee Arthroplasty Infected by Brucella Melitensis Septic Loosening and Long-Term Results of Two-Stage Revision Knee Arthroplasty. Journal of Surgery. 2014;10:241–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasim RA, Araj GF, Afeiche NE, Tabbarah ZA. Brucella infection in total hip replacement: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:65–7. doi: 10.1080/00365540310017456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klassov Y, Klassov T, Peretz O, Benkovich V. Review of periprosthetic infection of Brucellosis with presentation of a case report. American Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;12:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis JM, Folb J, Kalra S, Squire SB, Taegtmeyer M, Beeching NJ. Brucella melitensis prosthetic joint infection in a traveller returning to the UK from Thailand: Case report and review of the literature. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:444–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowe CF, Showler AJ, Perera S, McIntyre S, Qureshi R, Patel SN. et al. Hospital-associated transmission of Brucella melitensis outside the laboratory. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:150–2. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.141247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malizos KN, Makris CA, Soucacos PN. Total knee arthroplasties infected by Brucella melitensis: a case report. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 1997;26:283–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marbach F, Saiah L, Fischer JF, Huismans J, Cometta A. [Infection of a total knee prosthesis with Brucella spp] Rev Med Suisse. 2007;3:1007–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchese M, Bianchi G, Cavenago C. Total knee prosthesis infection by Brucella melitensis: case report and review of the literature. Journal of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 2006;7:150–3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oner M, Guney A, Halici M, Kafadar I. Septic Loosening Due to Brucella Melitensis After Bilateral Knee Prosthesis and Two-Stage Total Knee Prosthesis Revision. Erciyes Tip Dergisi/Erciyes Med J. 2012;34:97–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ortega-Andreu M, Rodriguez-Merchan EC, Aguera-Gavalda M. Brucellosis as a cause of septic loosening of total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:384–7. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.30284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orti A, Roig P, Alcala R, Navarro V, Salavert M, Martin C. et al. Brucellar prosthetic arthritis in a total knee replacement. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:843–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01700416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Iban MA, Crespo P, Diaz-Peletier R, Rozado AM, Lopez-Pardo A. Total hip arthroplasty infected by Brucella: a report of two cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2006;14:99–103. doi: 10.1177/230949900601400122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tassinari E, Di Motta D, Giardina F, Traina F, De Fine M, Toni A. Brucella infection in total knee arthroplasty. Case report and revision of the literature. Chir Organi Mov. 2008;92:55–9. doi: 10.1007/s12306-008-0031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tena D, Romanillos O, Rodriguez-Zapata M, de la Torre B, Perez-Pomata MT, Viana R. et al. Prosthetic hip infection due to Brucella melitensis: case report and literature review. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;58:481–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weil Y, Mattan Y, Liebergall M, Rahav G. Brucella prosthetic joint infection: a report of 3 cases and a review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:e81–6. doi: 10.1086/368084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wunschel M, Olszowski AM, Weissgerber P, Wulker N, Kluba T. [Chronic brucellosis: a rare cause of septic loosening of arthroplasties with high risk of laboratory-acquired infections] Z Orthop Unfall. 2011;149:33–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nichols M, Thompson D, Carothers JT, Klauber J, Stoddard RA, Guerra MA. et al. Brucella abortus exposure during an orthopedic surgical procedure in New Mexico, 2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:1072–3. doi: 10.1086/677155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Çetđn ES, Kaya S, Atay T, Demđrcđ M. Brucellar Prosthetic Arthritis of the Knee Detected with the Use of Blood Culture System For the Culture of Synovial Fluid. Fırat Tıp Dergisi. 2008;13:153–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mesner O, Riesenberg K, Biliar N, Borstein E, Bouhnik L, Peled N. et al. The many faces of human-to-human transmission of brucellosis: congenital infection and outbreak of nosocomial disease related to an unrecognized clinical case. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:e135–40. doi: 10.1086/523726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mert A, Ozaras R, Tabak F, Bilir M, Yilmaz M, Kurt C. et al. The sensitivity and specificity of Brucella agglutination tests. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;46:241–3. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, HICPAC t; http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/isolation/Isolation2007.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Almiron MA, Roset MS, Sanjuan N. The Aggregation of Brucella abortus Occurs Under Microaerobic Conditions and Promotes Desiccation Tolerance and Biofilm Formation. Open Microbiol J. 2013;7:87–91. doi: 10.2174/1874285801307010087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godefroid M, Svensson MV, Cambier P, Uzureau S, Mirabella A, De Bolle X. et al. Brucella melitensis 16M produces a mannan and other extracellular matrix components typical of a biofilm. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;59:364–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maves RC, Castillo R, Guillen A, Espinosa B, Meza R, Espinoza N. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Brucella melitensis isolates in Peru. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1279–81. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00979-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alp E, Doganay M. Current therapeutic strategy in spinal brucellosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:573–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colmenero JD, Ruiz-Mesa JD, Plata A, Bermudez P, Martin-Rico P, Queipo-Ortuno MI. et al. Clinical findings, therapeutic approach, and outcome of brucellar vertebral osteomyelitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:426–33. doi: 10.1086/525266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ulu-Kilic A, Karakas A, Erdem H, Turker T, Inal AS, Ak O. et al. Update on treatment options for spinal brucellosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O75–82. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pappas G, Seitaridis S, Akritidis N, Tsianos E. Treatment of brucella spondylitis: lessons from an impossible meta-analysis and initial report of efficacy of a fluoroquinolone-containing regimen. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;24:502–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]