Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The positive effects of physical activities during pregnancy are totally recognized but due to lack of knowledge and negative aspect toward it, physical activities decrease throughout the pregnancy period. To find the appropriate model to enhance physical activity during pregnancy, the education that are focused on health belief constructs about physical activity during pregnancy, were assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This was a semi-experimental study conducted on 90 pregnant women in their first trimester that were divided into two groups of control and intervention. After assessing health belief model (HBM) constructs and measuring the duration of severe/moderate-intensity) physical activity through a questionnaire, participants were divided into two groups of 45. The intervention group received education about physical activity based on HBM and the control group received dental health education. In the second trimester again, the constructs of HBM and the duration of physical activities were evaluated. Significant level was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS:

Data analysis showed that level of perceived susceptibility/severity and perceived benefits and also the level of appealing physical activity (P < 0.05), had a significant increase in the intervention group after the education, but the mean of the severe/moderate-intensity physical activity with did not rise to 150 min/week.

CONCLUSION:

Study results showed that education based on HBM could lead to an increase in physical activity during pregnancy by increasing the level of health beliefs in pregnant women, but this increase does not reach the adequate level.

Keywords: Health belief model, physical activity, pregnancy

Introduction

Regular physical activity during pregnancy has known beneficial effects on the health of the mother and the fetus. Studies have shown that women with less active lifestyle would be at the risk of gestational diabetes,[1] gestational hypertension and preeclampsia,[2] depression,[3] and abnormal weight gain during pregnancy[4] less than other women. Also reduced risk of fetus macrosomia following better mother's better metabolic condition[5] would enhance the outcome of the pregnancy and guarantee the safety of the fetus.

These benefits would be gained if the intensity and the duration of physical activities would be adequate. The American College recommends that pregnant women without any medical and midwifery problems should be encouraged to do the moderate/severe-intensity physical activity for at least 30 min 5 days a week.[6] However, expanded use of technology has led people toward inactive lifestyle and has made them prone to its consequences.

It has been reported that 60% of Iranian women do not have an appropriate physical activity and start their pregnancy in a sedentary lifestyle.[7] The physical condition of the body during pregnancy would decrease physical activity in its turn. Studies have revealed a progressive decline in physical activity during pregnancy[8] and modification of this lifestyle during pregnancy requires recommendations to do physical activity outside the routine lifestyle; an issue which is in contrast with the traditional beliefs of people about the need of pregnant women to rest and reduce their activities.[9]

Furthermore, many of the pregnancies especially in developing countries happen without planning[10] and any preconception care, therefore, the first contact between women and health care system happens when they are pregnant. Therefore, pregnancy could be a good opportunity to give health-related training.

Pregnant women are more susceptible toward matters that threaten their child and their own safety and strategies to avoid their consequences.[11]

They prefer to follow recommendations that would allow them to go through their pregnancy safely. Sensitivity of pregnant women to protect the health of the fetus may provide a useful psychological background for educational programs which focuses on increasing perceived susceptibility and sensitivity to behavior. Therefore, they might be more receptive of behavior changing interventions. Although during pregnancy cares most of the information would be transmitted to women, not all of them would be followed by a change in behavior. In this situation, training interventions that could target their susceptibility toward adequate behaviors might be effective.

One of the health enhancing models is the health belief model (HBM). This model is based on this fact that people would execute health-related behaviors when they have positive expectations and realize a factor's threats and believe that those behaviors could protect them from incidence of these threats.[12]

Therefore, the theoretical base of the present study was based on the fact that training pregnant women about the threats of inactivity and benefits of physical activity would lead to protecting them from those threats by increasing moderate to severe intensity physical activity.

Materials and Methods

This was a semi-experimental randomized double-blinded study that was conducted on 90 pregnant women after being approved by the Ethical Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and Ilam University of Medical Sciences.

Participants

Study population consisted of pregnant women with singletons aged from 18 to 35 years who referred to Ilam Medical Centers from July to October of 2014 to receive prenatal care in their first trimester. Inclusion criterion was not having any medical and midwifery limitations to perform moderate/severe-intensity physical activities. Exclusion criteria were termination of the pregnancy before the end of the study and incidence of any problem that would lead to medical limitations for performing moderate to severe intensity physical activity during the study.

Recruiting and proceedings

Four health care centers working under supervision of Ilam University of Medical Sciences were randomly selected and in each center two trained midwives (BS degree) assisted the study.

From holidays, 3 days were randomly selected and in those days during consecutive weeks sampling was conducted; in the way that eligible women for the study were selected by the first staff and then after explaining the participation progress written consent form was filled by them.

After completing demographic data, physical activity and health belief questionnaires were filled by the participants (self-report). Then for random allocation to two groups of intervention and control the participants were referred to the second staff. Random allocation was conducted by the block method. The intervention group received education about physical activity, and the control group received education about dental hygiene during pregnancy. The theoretical basis of the physical activity education was HBM. The training package was prepared by experts by reviewing previous studies and also expert opinions in an expert panel. The education were presented face to face for 30–40 min through a mutual interaction and simply focused on the effects of physical activities on metabolic condition of pregnant women and its benefits for the body of pregnant women and the health of their fetus.

Both groups received illustrated instruction pamphlets about safe training exercises during pregnancy that included recommendations about physical activities and their benefits.

Routine education was provided for both groups. The physical activity and health belief questionnaires were given to the participants by the first staff again after 4–6 weeks during second trimester visits. The first staff was blinded about the group of the participants.

From all 92 eligible women that were selected during sampling 2 were excluded due to medical limitations for performing physical activities. Finally, 90 participants completed that study.

Measurement tools

Evaluated variables in this study were demographic data, HBM constructs (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, and perceived barriers), and the duration of moderate/severe intensity physical activity in participants. Measurement tool to evaluate health belief structures was a 20 item questionnaire that was designed by literature review[12] and expert opinions based on Likert scale (0-4).

Cronbach's α to assess internal reliability for perceived susceptibility was 0.75, for perceived severity was 0.79, for perceived benefits was 0.75, and for perceived barriers was 0.8.

Sample questions: (1) Perceived susceptibility: Inactivity during pregnancy has negative effects on the health of fetus. (2) Perceived severity: The consequences of inactive lifestyle would endanger the health of pregnant women. (3) Perceived benefits: Physical activity could help women to go through pregnancy without any complications. (4) Perceived barriers: Physical activity during pregnancy would be tiring.

The evaluation of physical activity was done using pregnancy physical activity questionnaire which assessed the minutes that were consumed for household activities, occupational activities, exercising, hiking and transportation and the duration of inactivity based on the intensity of physical activity during day and week.[13]

The intensity of activities was measured based on metabolic equivalent (MET). Physical activity with 1.5–3 MET was considered low intensity activity, 3–6 MET was moderate, and more than 6 MET was severe physical activity. The total time of activities with MET < 1.5 was considered as the sedentary time. Sleeping time was not considered in the evaluations. The duration of leisure activities was calculated by mathematically adding it to the time of moderate to severe exercising and hiking by minute through each week. Besides the duration of leisure activities, the duration of moderate/severe intensity household and occupational activities were also considered as physical activity variables.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The number of samples was calculated by α equal to 0.05 and β to 0.8. Statistical analysis was done using Chi-square, t-test, one-way variance analysis, post hoc test, and multivariable regression with the significance level of P < 0.05.

Results

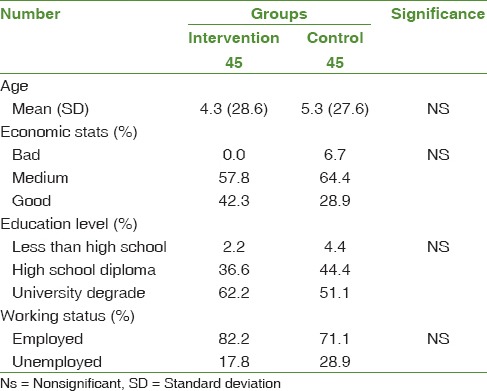

Data analysis on participants of the intervention and the control group showed that groups had no significant differences in their demographic data [Table 1].

Table 1.

Background characteristics of subjects

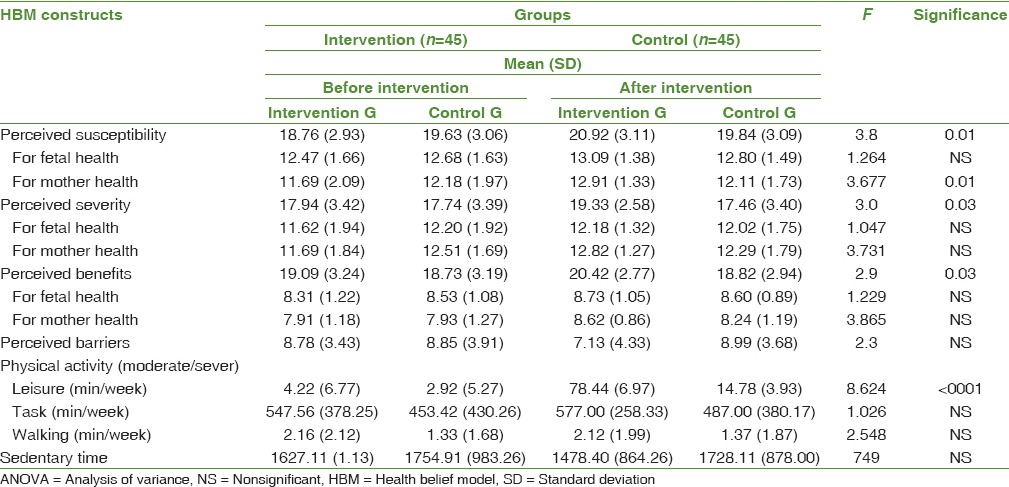

The HBM constructs were compared using analysis of variance test between both groups and also before and 4 weeks after the education and the results are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Comparison of health belief constructs and physical activity between two groups by 2 times (ANOVA)

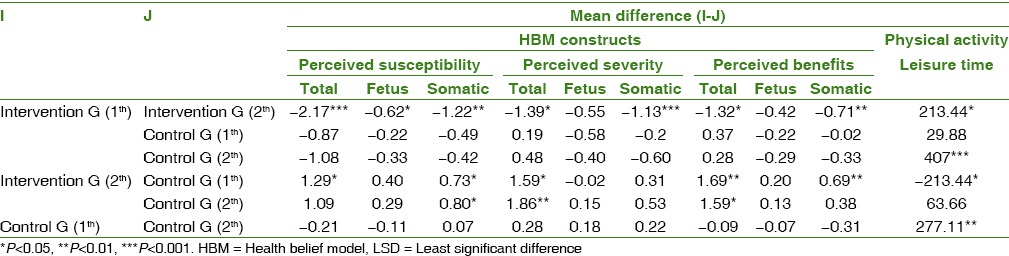

Table 3.

The results of LSD test (two groups by 4 times)

Results showed that perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, and time to engage in physical activity were significant difference in both groups by two sections; but after intervention, perceived susceptibility was not significant difference in both groups.

In the intervention group, the perceived susceptibility, perceived severity and perceived benefits of the physical activity related to mothers’ health were increased in second trimester: But, perceived severity and perceived benefits of the physical activity related to fetal health were not significant difference between before and after intervention.

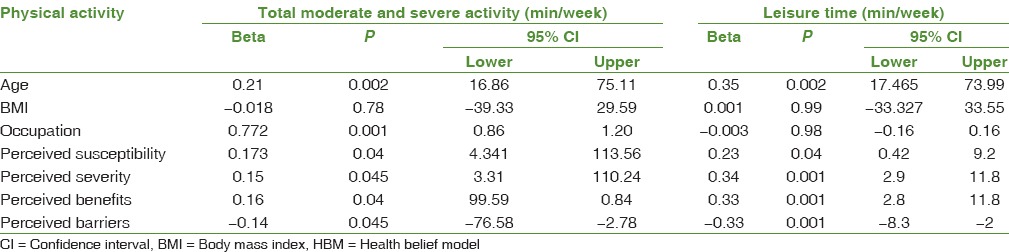

Evaluating the relation between HBM constructs and the duration of physical activity using multivariable regression test adjusted for age, body mass index, and being employed showed that the moderate/severe-intensity physical activity was independently and positively related to the perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and perceived benefits [Table 4].

Table 4.

The relations between HBM constructs and physical activity

Discussion

The main goal of the present study was to evaluate the effect of HBM based education on physical activities in pregnant women. Therefore, the constructs of HBM and the duration of moderate/severe-intensity physical activity were compared between the intervention and the control group in two sections. Also, the relation between health belief structures and physical activity was evaluated.

Results showed that training pregnant women in their first trimester would increase their perceived threats about effects of inactivity. Furthermore, this education approach was effective in recognizing the benefits of active lifestyle. By the way, results showed that this education made no significant difference in understanding the obstacles of performing physical activities.

In contrast with the results of the present study, based on the HBM, the increase in perceived threats (perceived susceptibility/severity) is followed by an increase in the perceived benefits and a decrease in perceived barriers of health-related behaviors. These results would confirm the results of other studies that have shown the effect of interpersonal interactions on the physical activity of pregnant women.[14,15] While the HBM is mainly insisting on the individual's beliefs some studies have shown that family members’ expectations have an important effect physical activity behavior[14] and the present study revealed that HBM-based education for pregnant women could possibly not limit the effect of these interventions entirely.

Many family members of pregnant women would encourage them to reduce their moderate/severe physical activity to remain safe during pregnancy[15] while a little percent of women would consider physician's advice, the best guideline for health-related behaviors.[16]

By the way, although the results of the present study showed that moderate/severe-intensity physical activity was increased in the second trimester in both groups, but the increase in leisure physical activities of the intervention group was statistically significant.

The increase in moderate/severe intensity physical activity of pregnant women in the second trimester has also been reported before.[8] Passing through a stage of pregnancy that is accompanied with morning sickness and fatigue and starting a stage with relatively enhanced condition when symptoms of pregnancy are not showing much yet; could be an explanation for this change in physical activity behavior. Also, this change in physical activity behavior could be the result of education received during pregnancy routine check-ups. But the significant increase of moderate/severe leisure physical activity in the intervention group and its significant difference with the control group was definitely due to received education.

Furthermore, the observed relation between moderate/severe intensity physical activity and health belief constructs could explain the pattern of physical activity in pregnant women. Also, the results showed that using HBM for education physical activity in pregnant women could increase perceived susceptibility and severity to improve the adequate physical activity for women. But considering the mean duration of moderate/severe intensity physical activity in this study showed that using this model as an individual model do not have the potential to improve the active lifestyle to its recommended range of 150 min/week.[6]

The lack of reduction in perceived obstacles following education based on HBM could be one of the reasons for the inadequate increase in physical activity during pregnancy. Physical activity is under the influence of culture and in societies where the knowledge about the importance of physical activity is not enough[17] and these behaviors have not yet found their true position as valuable behaviors to maintain health; these cultural obstacles could strongly block the change in physical activity behavior.

Another result of this study was the lack of effect of education on the health belief structures of physical activity about the health of fetus and the perceived obstacle to physical activity about the health of fetus is one of the most important obstacles of physical activity during pregnancy.

Records have shown that during pregnancy women mostly concern about their fetus's health rather than their own.[18,19] Pregnant women consider themselves in charge of their child's health and believe that their behaviors would affect the health of their child[19] and their concerns about harming the health of their fetus by performing physical activity[19,20] would affect the level of their physical activity.[21] The results of this study showed that using this training method for a period during pregnancy could not overcome these concerns; in a way that education were not able to change mothers’ perceived susceptibility and threats about the safety of fetus as much as somatic symptoms.

On the other hand, although HBM-based education could not enhance active lifestyle adequately and as it was expected in a limited period of time, an increase in physical activity in women over time and after gaining physical fitness, following performing moderate to severe intensity physical activities is possible. Therefore, not following up the physical activity of participants in their third trimester is one of the limitations of this study.

Conclusion

This study showed that education during pregnancy for performing adequate physical activities with just individual approach could not make women's lifestyle active and probably a combination of individual and interpersonal models could be more effective.

Financial support and sponsorship

Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (GN: 393270).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for funding the survey (Grant Number: 393270).

References

- 1.Hawkins M, Hosker M, Marcus BH, Rosal MC, Braun B, Stanek EJ, 3rd, et al. A pregnancy lifestyle intervention to prevent gestational diabetes risk factors in overweight Hispanic women: A feasibility randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2015;32:108–15. doi: 10.1111/dme.12601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aune D, Saugstad OD, Henriksen T, Tonstad S. Physical activity and the risk of preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2014;25:331–43. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nordhagen IH, Sundgot-Borgen J. Physical activity among pregnant women in relation to pregnancy-related complaints and symptoms of depression. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2002;122:470–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haakstad LA, Voldner N, Henriksen T, Bø K. Physical activity level and weight gain in a cohort of pregnant Norwegian women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86:559–64. doi: 10.1080/00016340601185301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruifrok AE, Althuizen E, Oostdam N, van Mechelen W, Mol BW, de Groot CJ, et al. The relationship of objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour with gestational weight gain and birth weight. J Pregnancy 2014. 2014:567379. doi: 10.1155/2014/567379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Artal R, O’Toole M. Guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists for exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:6–12. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.37.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davari Tanha F, Ghajarzadeh M, Mohseni M, Shariat M, Ranjbar M. Is ACOG guideline helpful for encouraging pregnant women to do exercise during pregnancy? Acta Med Iran. 2014;52:458–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evenson KR. Towards an understanding of change in physical activity from pregnancy through postpartum. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2011;12:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doran F, O’Brien AP. A brief report of attitudes towards physical activity during pregnancy. Health Promot J Austr. 2007;18:155–8. doi: 10.1071/he07155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moosazadeh M, Nekoei-Moghadam M, Emrani Z, Amiresmaili M. Prevalence of unwanted pregnancy in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014;29:e277–90. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohman SG, Grunewald C, Waldenström U. Women's worries during pregnancy: Testing the Cambridge Worry Scale on 200 Swedish women. Scand J Caring Sci. 2003;17:148–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2003.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. 4th ed. San Fransisco, CA: Wiley & Sons; 2008. Models of individual health behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, Hosmer D, Markenson G, Freedson PS. Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1750–60. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000142303.49306.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Symons Downs D, Hausenblas HA. Women's exercise beliefs and behaviors during their pregnancy and postpartum. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thornton PL, Kieffer EC, Salabarría-Peña Y, Odoms-Young A, Willis SK, Kim H, et al. Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: The role of social support. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sui Z, Turnbull DA, Dodd JM. Overweight and obese women's perceptions about making healthy change during pregnancy: A mixed method study. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:1879–87. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noohi E, Nazemzadeh M, Nakhei N. The study of knowledge, attitude and practice of puerperal women about exercise during pregnancy. Iran J Nurs. 2010;23:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weir Z, Bush J, Robson SC, McParlin C, Rankin J, Bell R. Physical activity in pregnancy: A qualitative study of the beliefs of overweight and obese pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke PE, Gross H. Women's behaviour, beliefs and information sources about physical exercise in pregnancy. Midwifery. 2004;20:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncombe D, Wertheim EH, Skouteris H, Paxton SJ, Kelly L. Factors related to exercise over the course of pregnancy including women's beliefs about the safety of exercise during pregnancy. Midwifery. 2009;25:430–8. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hausenblas H, Downs DS, Giacobbi P, Tuccitto D, Cook B. A multilevel examination of exercise intention and behavior during pregnancy. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:2555–61. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]