Abstract

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infections continue to be a serious emerging disease problem internationally with well over 1000 cases and a major outbreak outside of the Middle East region. While the hypothesis that dromedary camels are the likely major source of MERS-CoV infection in humans is gaining acceptance, conjecture continues over the original natural reservoir host(s) and specifically the role of bats in the emergence of the virus. Dromedary camels were imported to Australia, principally between 1880 and 1907 and have since become a large feral population inhabiting extensive parts of the continent. Here we report that during a focussed surveillance study, no serological evidence was found for the presence of MERS-CoV in the camels in the Australian population. This finding presents various hypotheses about the timing of the emergence and spread of MERS-CoV throughout populations of camels in Africa and Asia, which can be partially resolved by testing sera from camels from the original source region, which we have inferred was mainly northwestern Pakistan. In addition, we identify bat species which overlap (or neighbour) the range of the Australian camel population with a higher likelihood of carrying CoVs of the same lineage as MERS-CoV. Both of these proposed follow-on studies are examples of “proactive surveillance”, a concept that has particular relevance to a One Health approach to emerging zoonotic diseases with a complex epidemiology and aetiology.

Keywords: Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Coronavirus (CoV), Camels, Bats, Serological surveillance

Introduction

Since the first detection and isolation of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in September 2012 from a fatal human case in Saudi Arabia [1], there have been more than 1000 human cases reported with a mortality rate of approximately 40% [2]. Although the primary cases are limited to nations in the Arabian Peninsula, secondary cases have been reported in many countries outside of the region, with the latest outbreak in South Korea already claiming 36 lives with more than 185 confirmed infections [3].

In contrast to the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which was introduced into the human population through a single or a limited number of spill-over event(s) [4], [5], current epidemiological studies suggest that there have been multiple introductions of different MERS-CoV strains into human population from animal reservoir(s) [6]. For SARS-CoV, there is now increasing evidence indicating that it is a bat-borne virus transmitted to humans via intermediate hosts such as palm civets and raccoon dogs [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. For MERS-CoV, the natural reservoir host(s) has not yet been determined, nor how different strains of the virus have been transmitted to human populations on multiple occasions since its first discovery in 2012 [6]. Although there are reports of MERS-like CoVs in different bats around the world, discovery of closely related viruses and virus-neutralising antibodies in dromedary camels has led to the hypothesis that they are likely to be the major reservoir of MERS-CoV and camel-to-human transmission is the main route of spill-over events [6]. However, it is presently not clear whether MERS-CoV was introduced into the camel populations recently or whether it has adapted to camels as a natural reservoir from ancient times. A retrospective search for MERS-CoV antibodies indicated that the virus was circulating among the camel populations in the Middle East and Africa as early as 1992 and 1983, respectively [12], [13], [14], [15]. In a recent study, the detection of a MERS-CoV conspecific virus from an African bat suggests that the MERS-CoV may have originated from an African bat, followed by bat-to-camel transmission in Africa, then the introduction of MERS-CoV to the Middle East through camel exportation/importation [6], [16].

In this context, it was hypothesized that examining the serological status of Australian camels may help elucidate when MERS-CoV entered the camel population. Dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) were introduced into Australia from the mid-19th century to assist with exploration and development of the arid centre of the continent [17]. Between 1840 and 1907 many thousands of camels were imported into Australia, into an area ranging from Central Australia to the De Grey River in Western Australia. As rail services extended north to Alice Springs in Central Australia in 1929, and with the subsequent growth of motor transport, many working camels were turned loose and their feral progeny were able to survive and breed in the desert.

Since this time, the feral camel population in central Australia has undergone an exponential increase. In 1966, the population was estimated to be 15,000–20,000, and by the mid-1980s the estimate increased to a minimum population of 43,000 [18]. By 2008, the minimum population was re-estimated to be about 1 million animals [19], and there was increasing concern of the economic, social and environmental damage the uncontrolled population was causing [20]. In response, plans have been adopted for population control, including a large culling operation between 2010 and 2014, when over 150,000 camels were killed [21]. Currently Australia has the largest herd of camels anywhere in the world, and the only population of wild camels. Long-term sustainable control measures to permanently maintain a lower population density are focused on developing a viable commercialisation, particularly based on mustering to process meat for human consumption for the export market.

As a first step toward a risk assessment of potential bat-to-camel transmission of MERS-CoV like pathogens in Australia, we examined the current camel distribution in Australia and its overlap with the habitat of native bat species related to those from which MERS-CoV-like viruses have been detected. Furthermore, we conducted a MERS-CoV sero-prevalence study on more than 300 camel serum samples collected from three different locations at four time points from December 2013 to August 2014.

Materials and methods

Camel serum sampling

Blood or serum samples were collected from two locations, an abattoir that processes wild caught and farmed camels mainly for export, and from an area nearby Alice Springs, Northern Territory during a muster for the Department of Agriculture. Samples were collected on the 16th December 2013, 22nd January 2014, 17th April 2014 and 6th August 2014, respectively (see Table 1 for detail). This study was approved by both the Federal and State Agricultural Departments via the Animal Health Committee and by the Federal Department of Health in Australia.

Table 1.

Camel serum samples collected in this study.

| Sample# | Provider of samples | Date of collection | Animal originated from |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–31 | Abattoir | 16-12-2013 | Central Australia |

| 32–131 | Abattoir | 22-01-2014 | Central Australia |

| 132–231 | Abattoir | 17-04-2014 | Central Australia |

| 232–307 | Camel muster | 06-08-2014 | Central Australia |

Luminex antibody test

A Luminex-based assay was developed using recombinant nucleocapsid (N) proteins of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV using methodology established in our group for henipaviruses [22]. Recombinant CoV N proteins were produced in E. coli and purified directly from SDS-PAGE gels as previously described [23]. For coating onto Luminex beads, a total of 100 μg each of the two N proteins were coupled onto 100 μl of bead set 28 (SARS-CoV) and bead set 34 (MERS-CoV), respectively. Briefly, coupled microsphere sets were vortexed and sonicated prior to dilution in PBS-T containing 2% skim milk and transferred to 96-well plate. The diluent was removed using an automated magnetic vacuum manifold followed by the addition of 100 μl of camel sera diluted 1:100 in PBS-T and incubated, shaking for 30 min at room temperature. Positive control camel sera used in this assay were derived from the natural infection of dromedary camels in Egypt during 2013 as part of a seroepidemiology study [24]. The serum was removed and the plate was washed twice with PBS-T followed by addition of Biotinylated Protein A (Pierce, Rockford, USA) and Protein G (Pierce, Rockford, USA) conjugates and incubated as described above. The conjugate was removed and the beads washed twice with PBS-T followed by addition of Streptavidin–phycoerythrin (Qiagen Pty Ltd, Australia) and a final incubation as described above. Assays were performed on a Bio-Plex Protein Array System integrated with Bio-Plex Manager Software (v 6.0) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., CA, USA). Results were recorded as median florescent intensity (MFI).

Virus neutralisation test (VNT)

VNT was conducted as previously described for SARS-CoV [10], [25]. Briefly, each camel serum was tested in duplicate by doubling dilution in EMEM starting at 1:10 out to 1:1280. To 50 μl of sera an equal volume of EMEM containing 200 TCID50 of a Dromedary camel isolate of MERS virus [24] was added and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Vero cells were then added to each well and the plates incubated at 37 °C and subsequently read for the presence of cytopathic effect (CPE) after 4 days. Neutralising titres were recorded at the dilution at which at least one duplicate well was negative for CPE. The same positive control camel sera were used in this assay.

Analysis of the distributions of the Australian feral camels and potential MERS-CoV reservoir bat species

MERS-CoV belongs to a distinct lineage (“C”) of the beta-coronavirus genus [26]. This lineage was initially defined from isolates from sampling in Hong Kong where two species of lineage C β-CoV were described: “Ty-Bat CoV HKU4” and “Pi-Bat CoV HKU5” [6].

On the assumption that lineage C β-CoVs are more likely to be found in Australian bats of the same genus as those from which they have been isolated overseas, we surveyed the peer-reviewed literature and the GenBank sequence repository for lineage C β-CoV - bat genera associations. Consequently, we identified seven Australian microbat species belonging to the families Vespertilionidae and Emballonuridae that satisfied this criterion.

There is little published literature on these seven species, and to determine potential overlap of their distribution with those of camels, we undertook habitat modelling distribution using Maxent version 3.3 [27]. As input for the modelling, we used the locational data stored within the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA) online database, which collates data on museum collections and sightings for most bat species of Australia (http://www.ala.org.au/). Predictor variables used were all the BioClim bioclimatic variables, Australian Land Use and Management Classification Version 7 and the NVIS Major Vegetation Subgroups (Version 4.1).

All modelling was undertaken at the resolution of 0.008° (30 s) using the WGS84 projection.

To determine if any of the selected bat species overlap the distribution of feral camels in central Australia, we undertook a similar Maxent habitat distribution modelling exercise for the latter. For this we used the “CamelScan” online database (http://www.feralscan.org.au/camelscan/) in addition to the sightings in the ALA. Modelling results were compared to the consolidated sighting and survey map published by Saalfeld and Edwards [19].

Results

Absence of MERS-CoV antibodies in Australian camels

Two different testing platforms were used to detect MERS-CoV antibodies in Australian camels. A Luminex assay based on the conserved and cross-reactive N proteins of both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV was used to detect any antibodies cross reactive with either of these two viruses whereas the MERS-CoV specific VNT was employed to confirm the potential presence of MERS-CoV infection in Australian camels as the VNT assay is known to be specific for MERS-CoV, and there is no cross-neutralisation between MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV or bovine-CoV [28].

As the results for all the Australian camels were negative by both Luminex and VNT assays for all 307 camel sera tested in this study, only results from selected serum samples (five individual samples from each batch) are given in Table 2 to allow a clearer presentation of the findings (see the full list in the online Supplementary Table S1). While the positive control camel sera produced neutralisation titres ranging from 1:400 to > 1:6400, all of the Australian camel sera had a neutralising titre to MERS-CoV < 1:10.

Table 2.

Luminex and VNT results of selected serum samples⁎.

| Samples | Luminex reading (MFU) |

VNT titre for MERS-CoV | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SARS N | MERS N | ||

| No serum control | 79 | 79 | ND |

| Horse control serum | 200 | 593 | ND |

| Horse SARS hyperimmune serum | 29,319 | 5649 | ND |

| Camel control serum | 147 | 191 | neg |

| Camel MERS positive serum | 178 | 8127 | 1:800 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016868 | ND | ND | 1:400 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016870 | ND | ND | 1:1600 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016872 | ND | ND | 1:800 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016874 | ND | ND | > 1:6400 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016876 | ND | ND | 1:800 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016880 | ND | ND | 1:3200 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016882 | ND | ND | 1:800 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016884 | ND | ND | > 1:6400 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016886 | ND | ND | 1:800 |

| Saudi Arabia 2313016888 | ND | ND | 1:3200 |

| Australian camel serum 1 | 153 | 655 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 2 | 112 | 827 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 3 | 131 | 480 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 4 | 95 | 518 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 5 | 148 | 733 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 20 | 1256 | 509 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 32 | 128 | 205 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 33 | 121 | 256 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 34 | 155 | 210 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 35 | 172 | 170 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 36 | 122 | 205 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 54 | 205 | 1377 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 132 | 104 | 458 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 133 | 165 | 353 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 134 | 124 | 389 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 135 | 106 | 209 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 136 | 95 | 189 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 232 | 433 | 722 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 233 | 137 | 172 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 234 | 188 | 204 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 235 | 161 | 202 | neg |

| Australian camel serum 236 | 166 | 209 | neg |

For the complete list of all 307 Australian camel serum samples, please see online Supplementary Table S1. ND, not done; neg, no neutralisation at a dilution of 1:10.

For the Luminex assay, there were only two samples giving a reading above 1000 MFI, the set cut-off for background binding. As shown in Table 2, serum 20 has MFU readings of 1256 and 509 for SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV N proteins, respectively, while serum 54 has 205 and 1377, respectively. However, in comparison to the MFU readings of positive control sera (ranging from 8127 to 29,319), these low range “potentially positive” readings were considered to be non-conclusive. The clear negative VNT results for these two samples confirmed that they did not contain MERS-CoV antibody.

Overlapping distribution of wild camels and bats in Australia

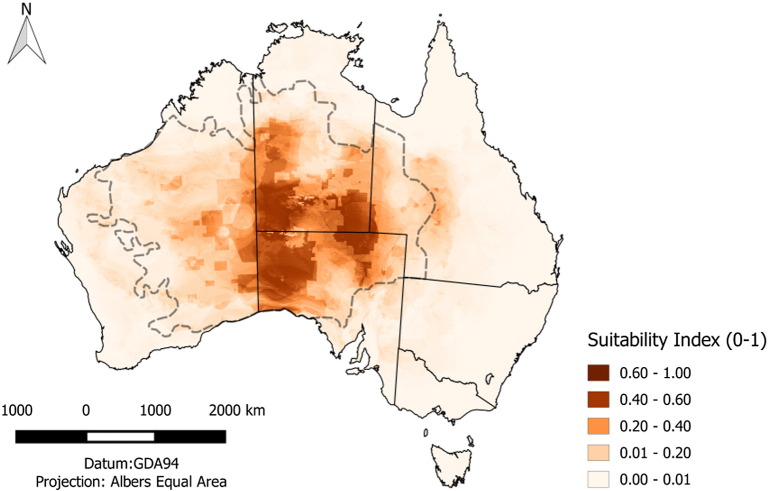

The total area predicted by the Maxent modelling to be potentially suitable for feral camels in Australia is 1,716,196 km2 (Fig. 1). This is less than the area identified by Saalfeld and Edwards [19] and may reflect the intensive culling during 2009–10 undertaken to reduce the impact of feral camels on the environment [21]. Note that the Australian camel can be considered one population, as there are no natural geographical boundaries leading to the formation of sub-populations.

Fig. 1.

The area predicted by Maxent to be potentially occupied by camels in central Australia based on sighting data. For comparison, the dashed line indicates the extent of the camel distribution in 2008 (at their maximum population size) estimated by Saalfeld and Edwards (2010) [19].

In total, we found 14 papers describing 56 unique isolates or sequences of lineage C β-CoV from microbats from Europe, Africa, Central America and East Asia, belonging to 11 genera (Table 3). The majority (89%) of the bat hosts from which the β-CoV C were isolated or sequenced belong to the family Vespertilionidae.

Table 3.

Bat families and genera in which lineage C β-CoVs have been identified and the number of species in these identified genera that are native to mainland Australia.

| Family | Genus | Country lineage C β-CoV isolated/sequenced | Number of isolates/unique sequences in Genbank | References to the isolates/sequences of the lineage C β-CoV | Number of bat species of the genus native to Australia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vespertilionidae | Eptesicus | Spain/Italy | 2 | [40], [41] | 0 |

| Vespertilionidae | Hypsugo | Spain/Italy | 2 | [40], [42] | 0 |

| Vespertilionidae | Neoromicia | South Africa | 1 | [16] | 0 |

| Vespertilionidae | Nyctalus | Italy | 1 | [42] | 0 |

| Vespertilionidae | Pipistrellus | Hong Kong/Italy/Romania /Ukraine/Netherlands |

28 | [42], [43], [44], [45], [46] | 2 |

| Vespertilionidae | Tylonycteris | Hong Kong/China | 15 | [43], [44], [47] | 0 |

| Vespertilionidae | Vespertilio | China | 1 | [48] | 0 |

| Emballonuridae | Taphozous | Saudi Arabia | 1 | [36] | 5 |

| Nycteridae | Nycteris | Ghana | 3 | [45] | 0 |

| Molossidae | Nyctinomops | Mexico | 1 | [49] | 0 |

| Mormoopidae | Pteronotus | Mexico | 1 | [50] | 0 |

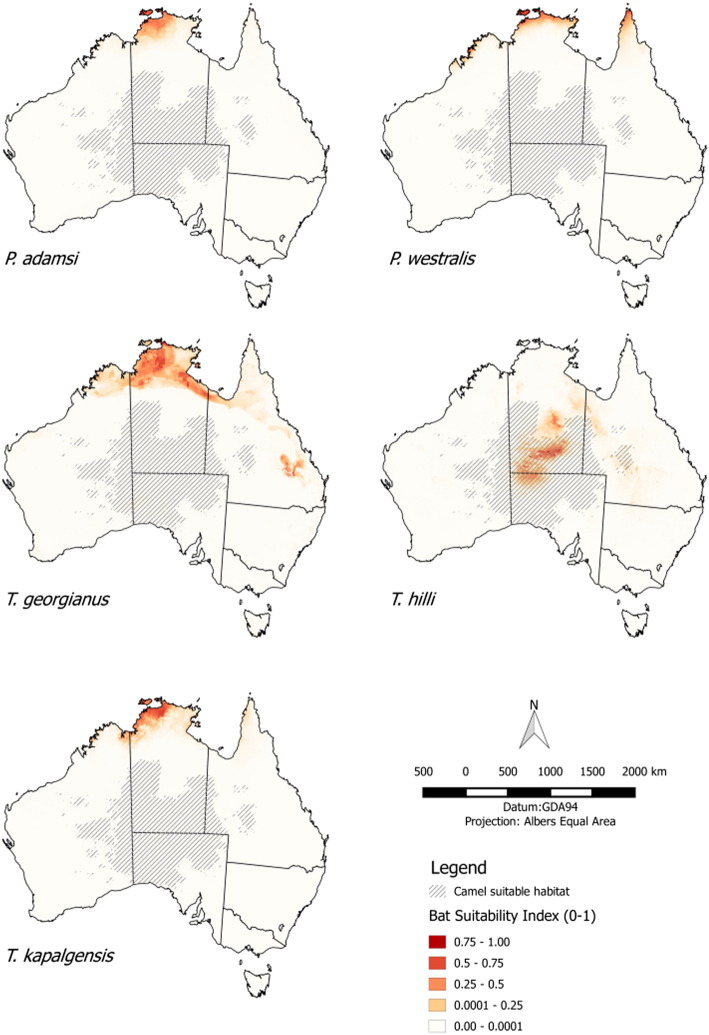

Comparison with the list of native species resident within mainland Australia showed 7 species, with 2 belonging to the genera Pipistrellus (Fam: Vespertilionidae) and 5 belonging to Taphozous (Fam: Emballonuridae) (Table 4). Of these 7 species, 2 are confined to the east coast of Australia, 4 have distributions bordering (but not overlapping) that of the camels, and only 1 species (Taphozous hilli) has a home range with significant overlap (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Australian bat species belonging to the genera shown to harbour lineage C β-CoVs (Table 3) and the extent to which their estimated home range overlaps that of the Australian feral camel population.

| Species | Family | Common name | Extent of home range estimated by Maxent modelling from sightings recorded in the ALA (km2) | Estimated home range overlap between bat species and camels (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pipistrellus adamsi | Vespertilionidae | Forest pipistrelle | 85,676 | 0% |

| Pipistrellus westralis | Vespertilionidae | Northern pipistrelle, | 99,161 | 0% |

| Taphozous georgianus | Emballonuridae | Common sheath-tailed bat | 350,588 | 0% |

| Taphozous hilli | Emballonuridae | Hill's sheath-tailed bat | 172,119 | 84.16% |

| Taphozous kapalgensis | Emballonuridae | Arnhem sheath-tailed bat | 113,442 | 0% |

| Taphozous australis | Emballonuridae | Coastal sheath-tailed bat | Insufficient data points | Assumed to be 0% as confined to the east coast of Australia |

| Taphozous troughtoni | Emballonuridae | Troughton's sheath-tailed bat | No location data held within ALA | Assumed to be 0% as confined to the east coast of Australia |

Fig. 2.

The home range estimated by Maxent modelling of the 5 selected species in Table 2 which overlap of are relatively closeby the distribution of the central Australian feral camels; (a) P. adamsi, (b) P. westralis; (c) T. georgianus; (d) T. hilli; and (e) T. kapalgensis.

Discussions

The feral camels in Australia represent the largest “herd” in the world, and furthermore, is the only free-ranging one. The origin of this population is not known for certain, as no records were kept during importation. However, the considered opinion is that they were mainly imported from British India [29]. This is also consistent with the historical records about the cameleers, who worked with the camels, who originated from the border areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan [30]. Furthermore, genetic studies have shown little genetic diversity in the Australian camel population, indicative of a strong “founder effect” [31], which suggests that the introductions were sourced from a restricted area. Therefore, pending confirmatory genetic studies of the northwest Pakistani camel populations, a working hypothesis is that the Australian feral camel population is derived from this area.

It is impossible to know for certain if the camels imported over 100 years ago from Pakistan carried MERS-CoV. Even if they did, it is possible that it was extinguished during the sea voyage. Alternatively, if the virus did manage to infect the Australian camel population, it is also plausible that it failed to establish long term sustained transmission due to the low population density of the camels when they were released into central Australia in the 1920s. Nevertheless, we propose that a careful collation of all the virological and ecological evidence will enable a reasoned assessment of the most probable status of the ancestors of the feral camels at the time of importation. Specifically, we suggest that investigations in Pakistan (as well as neighbouring Afghanistan and Iran) will provide an important piece of evidence, as to date there have not been any published reports of the MERS-CoV sero-status of these camel populations. Following on from this, if sampling in these countries show that MERS-CoV is not present in the current population, then the most probable explanation is that the virus was unlikely to have ever been introduced into Australia. By contrast, if the virus is found to be present, genetic studies of the virus may be able to partially resolve when it entered into the population, and thus if the camels exported to Australia might have been infected.

If as suggested, sero-surveys of camels are undertaken in western Asia and they are found to be negative, the results will also have wider implications than answering the question of whether MERS-CoV was ever present in Australia. To date the geographical origin of MERS-CoV is controversial, as although the disease is largely confined to the Arabian Peninsula, examination of stored serum collected in Sudan and Somalia from 1983 to 1984 has showed very high seropositivity for MERS-CoV [32]. As MERS-CoV has now been shown to be widespread throughout camel populations in northern, western and eastern Africa [33], there exists a plausible bat reservoir for a MERS-CoV ancestor [16], and there is a large export of camels from eastern Africa into the Arabian Peninsula [34], then a current working hypothesis is that Africa is the original source of the virus within camel populations. However, as other regional sources of the virus have not been investigated, the true geographical spread of the virus is not determined with certainty. Thus, a finding of an absence of MERS-CoV in the populations of camels in Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Australia would support the hypothesis that camels are not the original reservoir host of the MERS-CoV virus, and that a spillover event from a bat species into the camel population happened in relatively recent time.

Our assumption that Australian native bats are more likely to harbor lineage C β-CoVs if they belong to a genera from which these viruses have been isolated overseas requires some justification. The basis for it is the evidence for considerable co-evolution of α-CoV and β-CoV with their chiropteran hosts at the genus level [35]. Note that this does not apply at the family level, as both alpha and beta viruses occur in many chiropteran families [35].

The bat species (T. hilli) with a home that overlaps the central Australian camel distribution occupies a comparatively large area and occurs in an area of high camel density. As it is related to the species (Taphozous perforatus) from which a sequence almost identical to that of the index case of MERS-CoV was isolated in Saudi Arabia in 2012 [36], T. hilli would seem to be the priority for virological sampling. However, the sequence obtained from T. perfortatus was a single, short sequence (203 nucleotides), has not been independently confirmed and no actual isolate has subsequently been obtained [6]. By contrast, a virus from a species which occurs throughout east and southern Africa (Neoromicia capensis) has yielded a full genome sequence, which despite having less identity with MERS-CoV and not occurring in the Arabian Peninsula, is considered a more plausible natural reservoir [6]. As this species occurs within the family Vestpertilionidae, from which the majority of the lineage C β-CoV isolates have been obtained (Table 3), it is recommended that virological sampling of the Australian Vestpertilionidae species which occur to the north of the current camel distribution (Fig. 2) also be undertaken. With the recent advance of multiple serological profiling tools using a synthetic virome epitope library [37], it is theoretically feasible to examine total infection profiles of both bats and camels in the overlapped geographical locations. Such inter-species serological comparison will undoubtedly shed new light on the real risk and occurrence of spill-over events happening between these two groups of wildlife animals.

The concept of “active surveillance”, whereby surveys are undertaken to detect and measure the extent of a disease or pathogen is well established in public and animal health. While such active surveillance has a role in emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), it has obvious limitations in that it can only occur after the disease has emerged. Furthermore, there are challenges with diagnostics and the difficulty and expense of surveying for diseases of low prevalence, which is the situation for many EIDs in their initial stages. An approach which is gaining increasing recognition in the EID sciences is the use of “proactive surveillance” whereby potential “hotspots” for emergence and/or “reservoirs” are selected for surveys. We have provided an example of this “new” type of surveillance whereby we were able to recommend specific bat species to proactively target for sampling, and propose that this is particularly appropriate within the “One Health” approach to emerging infectious diseases.

Conclusion

At a first glance, it might seem that assessing the sero-status of feral camels, and the presence of CoVs in bats with potential contact with these camels has little relevance to understanding the epidemiology and evolution of MERS-CoV in the Arabian Peninsula. However, such are the complexities of the virus and the disease that many key discoveries have been made by examining animals at the margin of the problem areas. The initial discovery that camels might be the principal reservoir of MERS-CoV arose following exploratory testing of camel serum collected from the Canary Islands, which then led onto a more systematic survey of camels from the Arabian Peninsula [38]. Similarly, the discovery of a plausible ancestor virus to MERS-CoV arose from the sampling of a bat species in South Africa, even though the species does not occur within the Arabian Peninsula [16], [39]. The important lesson from these examples is that when dealing with an emerging infectious disease with a complex epidemiology, conventional outbreak investigations may not resolve key questions, and thus there is a need for studies which might appear tangential. Some of these, as in the examples cited, might result in important discoveries, but it needs to be accepted that most will not. However, we argue that within the context of “proactive surveillance”, then negative survey results can be immensely important in directing attention to where effort is needed, which in our example, is our recommendation for a follow-on sero-survey of camels in western Asia.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Serology results for all camel sera tested. (ND: not done; Neg: no neutralisation at a dilution of 1:10).

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Ron Fouchier for facilitating the collaboration, Bart Haagmanns and Chantal Reusken for the provision of materials, Rod Bowman from PathWest Laboratory Medicine WA for his assistance in facilitating the collection of samples from Alice Springs, Prasad Paradkar and Kim Blasdell for their critical reading of the manuscript. The study is funded in part by CSIRO and the CD-PHRG grant (to L-FW, CDPHRG/0006/2014).

Contributor Information

Peter A. Durr, Email: peter.durr@csiro.au.

Lin-Fa Wang, Email: linfa.wang@duke-nus.edu.sg.

References

- 1.Zaki A.M., van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ECDC . ECDC; Stockholm: 2015. Rapid Risk Assessment: Severe Respiratory Disease Associated with Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). 16th update, 05 June 2015. http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/coronavirus-infections/Pages/publications.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) — MERS-CoV in Republic of Korea at a Glance as of 29 July 2015. 2015. http://www.wpro.who.int/outbreaks_emergencies/wpro_coronavirus/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L.F., Eaton B.T. Bats, civets and the emergence of SARS. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007;315:325–344. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peiris J.S., Guan Y., Yuen K.Y. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Nat. Med. 2004;10:S88–S97. doi: 10.1038/nm1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan J.F., Lau S.K., To K.K., Cheng V.C., Woo P.C., Yuen K.Y. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015;28:465–522. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L.-F., Bats Eaton B. Wildlife and Emerging Zoonotic Diseases: The Biology, Circumstances and Consequences of Cross-Species Transmission. Springer; 2007. Civets and the emergence of SARS; pp. 325–344. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ge X.Y., Li J.L., Yang X.L., Chmura A.A., Zhu G., Epstein J.H. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2013;503:535–538. doi: 10.1038/nature12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan Y., Zheng B.J., He Y.Q., Liu X.L., Zhuang Z.X., Cheung C.L. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W., Shi Z., Yu M., Ren W., Smith C., Epstein J.H. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science. 2005;310:676–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1118391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Li K.S., Huang Y., Tsoi H.W., Wong B.H. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:14040–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alagaili A.N., Briese T., Mishra N., Kapoor V., Sameroff S.C., Burbelo P.D. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in dromedary camels in Saudi Arabia. mBio. 2014;5:e00884-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00884-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexandersen S., Kobinger G.P., Soule G., Wernery U. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibody reactors among camels in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, in 2005. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2014;61:105–108. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer B., Muller M.A., Corman V.M., Reusken C.B., Ritz D., Godeke G.J. Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedary camels, United Arab Emirates, 2003 and 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:552–559. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perera R.A., Wang P., Gomaa M.R., El-Shesheny R., Kandeil A., Bagato O. Seroepidemiology for MERS coronavirus using microneutralisation and pseudoparticle virus neutralisation assays reveal a high prevalence of antibody in dromedary camels in Egypt, June 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.36.20574. pii=20574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corman V.M., Ithete N.L., Richards L.R., Schoeman M.C., Preiser W., Drosten C. Rooting the phylogenetic tree of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus by characterization of a conspecific virus from an African bat. J. Virol. 2014;88:11297–11303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01498-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Letts G.A. Feral animals in the Northern Territory. Aust. Vet. J. 1964;40:84–88. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Short J., Caughley G., Grice D., Brown B. The distribution and relative abundance of camels in Australia. J. Arid Environ. 1988;15:91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saalfeld W., Edwards G. Distribution and abundance of the feral camel (Camelus dromedarius) in Australia. Rangel. J. 2010;32:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards G.P. Evaluation of the impacts of feral camels. Rangel. J. 2010;32:43–54. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart Q., Edwards G. Managing the impacts of feral camels in Australia. Aliens. 2013;33:12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bossart K.N., McEachern J.A., Hickey A.C., Choudhry V., Dimitrov D.S., Eaton B.T. Neutralization assays for differential henipavirus serology using Bio-Plex Protein Array Systems. J. Virol. Methods. 2007;142:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu M., Stevens V., Berry J.D., Crameri G., McEachern J., Tu C. Determination and application of immunodominant regions of SARS coronavirus spike and nucleocapsid proteins recognized by sera from different animal species. J. Immunol. Methods. 2008;331:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemida M.G., Chu D.K., Poon L.L., Perera R.A., Alhammadi M.A., Ng H.Y. MERS coronavirus in dromedary camel herd, Saudi Arabia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1231–1234. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu C., Crameri G., Kong X., Chen J., Sun Y., Yu M. Antibodies to SARS coronavirus in civets. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10:2244–2248. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Boheemen S., de Graaf M., Lauber C., Bestebroer T.M., Raj V.S., Zaki A.M. Genomic characterization of a newly discovered coronavirus associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome in humans. mBio. 2012;3 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phillips S.J., Anderson R.P., Schapire R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006;190:231–259. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemida M., Perera R., Al Jassim R., Kayali G., Siu L., Wang P. Seroepidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus in Saudi Arabia (1993) and Australia (2014) and characterisation of assay specificity. Euro Surveill. 2014;19 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.23.20828. pii: 20828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKnight T.L. Melbourne University Press; Carlton, Victoria: 1969. The Camel in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scriver P. Mosques, Ghantowns and Cameleers in the settlement history of Colonial Australia. Fabrications. 2004;13:19–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spencer P.B.S., Woolnough A.P. Assessment and genetic characterisation of Australian camels using microsatellite polymorphisms. Livest. Sci. 2010;129:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muller M.A., Corman V.M., Jores J., Meyer B., Younan M., Liljander A. MERS coronavirus neutralizing antibodies in camels, Eastern Africa, 1983–1997. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:2093–2095. doi: 10.3201/eid2012.141026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reusken C.B., Messadi L., Feyisa A., Ularamu H., Godeke G.J., Danmarwa A. Geographic distribution of MERS coronavirus among dromedary camels, Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1370–1374. doi: 10.3201/eid2008.140590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gossner C., Danielson N., Gervelmeyer A., Berthe F., Faye B., Kaasik Aaslav K. Human-dromedary camel interactions and the risk of acquiring zoonotic Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Zoonoses Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1111/zph.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drexler J.F., Corman V.M., Drosten C. Ecology, evolution and classification of bat coronaviruses in the aftermath of SARS. Antivir. Res. 2014;101:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Memish Z.A., Mishra N., Olival K.J., Fagbo S.F., Kapoor V., Epstein J.H. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bats, Saudi Arabia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1819–1823. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.131172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu G.J., Kula T., Xu Q., Li M.Z., Vernon S.D., Ndung'u T. Comprehensive serological profiling of human populations using a synthetic human virome. Science. 2015;348:aaa0698. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reusken C.B., Haagmans B.L., Muller M.A., Gutierrez C., Godeke G.J., Meyer B. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: a comparative serological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:859–866. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70164-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ithete N.L., Stoffberg S., Corman V.M., Cottontail V.M., Richards L.R., Schoeman M.C. Close relative of human Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bat, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1697–1699. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Falcon A., Vazquez-Moron S., Casas I., Aznar C., Ruiz G., Pozo F. Detection of alpha and betacoronaviruses in multiple Iberian bat species. Arch. Virol. 2011;156:1883–1890. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Benedictis P., Marciano S., Scaravelli D., Priori P., Zecchin B., Capua I. Alpha and lineage C betaCoV infections in Italian bats. Virus Genes. 2014;48:366–371. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-1008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lelli D., Papetti A., Sabelli C., Rosti E., Moreno A., Boniotti M.B. Detection of coronaviruses in bats of various species in Italy. Viruses. 2013;5:2679–2689. doi: 10.3390/v5112679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woo P.C., Wang M., Lau S.K., Xu H., Poon R.W., Guo R. Comparative analysis of twelve genomes of three novel group 2c and group 2d coronaviruses reveals unique group and subgroup features. J. Virol. 2007;81:1574–1585. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02182-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau S.K., Li K.S., Tsang A.K., Lam C.S., Ahmed S., Chen H. Genetic characterization of Betacoronavirus lineage C viruses in bats reveals marked sequence divergence in the spike protein of pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 in Japanese pipistrelle: implications for the origin of the novel Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 2013;87:8638–8650. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01055-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Annan A., Baldwin H.J., Corman V.M., Klose S.M., Owusu M., Nkrumah E.E. Human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012-related viruses in bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:456–459. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.121503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reusken C.B., Lina P.H., Pielaat A., de Vries A., Dam-Deisz C., Adema J. Circula-tion of group 2 coronaviruses in a bat species common to urban areas in Western Europe. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:785–791. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2009.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang X.C., Zhang J.X., Zhang S.Y., Wang P., Fan X.H., Li L.F. Prevalence and genetic diversity of coronaviruses in bats from China. J. Virol. 2006;80:7481–7490. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00697-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang L., Wu Z., Ren X., Yang F., Zhang J., He G. MERS-related betacoronavirus in Vespertilio superans bats, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1260–1262. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anthony S.J., Ojeda-Flores R., Rico-Chavez O., Navarrete-Macias I., Zambrana-Torrelio C.M., Rostal M.K. Coronaviruses in bats from Mexico. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:1028–1038. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.049759-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goes L.G., Ruvalcaba S.G., Campos A.A., Queiroz L.H., de Carvalho C., Jerez J.A. Novel bat coronaviruses, Brazil and Mexico. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:1711–1713. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Serology results for all camel sera tested. (ND: not done; Neg: no neutralisation at a dilution of 1:10).