Abstract

Originating from Africa, Usutu virus (USUV) first emerged in Europe in 2001. This mosquito-borne flavivirus caused high mortality rates in its bird reservoirs, which strongly resembled the introduction of West Nile virus (WNV) in 1999 in the United States. Mosquitoes infected with USUV incidentally transmit the virus to other vertebrates, including humans, which can result in neuroinvasive disease. USUV and WNV co-circulate in parts of southern Europe, but the distribution of USUV extends into central and northwestern Europe. In the field, both viruses have been detected in the northern house mosquito Culex pipiens, of which the potential for USUV transmission is unknown. To understand the transmission dynamics and assess the potential spread of USUV, we determined the vector competence of C. pipiens for USUV and compared it with the well characterized WNV. We show for the first time that northwestern European mosquitoes are highly effective vectors for USUV, with infection rates of 11% at 18 °C and 53% at 23 °C, which are comparable with values obtained for WNV. Interestingly, at a high temperature of 28 °C, mosquitoes became more effectively infected with USUV (90%) than with WNV (58%), which could be attributed to barriers in the mosquito midgut. Small RNA deep sequencing of infected mosquitoes showed for both viruses a strong bias for 21-nucleotide small interfering (si)RNAs, which map across the entire viral genome both on the sense and antisense strand. No evidence for viral PIWI-associated RNA (piRNA) was found, suggesting that the siRNA pathway is the major small RNA pathway that targets USUV and WNV infection in C. pipiens mosquitoes.

Keywords: Usutu virus, West Nile virus, Culex pipiens, Mosquitoes, Transmission, Antiviral RNAi

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Northwestern European mosquitoes are highly effective vectors for USUV.

-

•

Culex pipiens is significantly more competent for USUV than for WNV at 28 °C.

-

•

The siRNA but not the piRNA pathway targets USUV and WNV infections in C. pipiens.

-

•

USUV may be a prelude to WNV transmission in northwestern Europe.

Introduction

In the last two decades a number of clinically significant arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) have emerged and re-emerged in continental Europe. Autochthonous transmission of dengue virus has occurred in France in 2014 [1] and chikungunya virus transmission has been recorded in Italy (2007) [2] and France (2010, 2014) [3], [4]. Both of these viruses are transmitted by the invasive Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus, which has colonized parts of Europe [5]. Native Culex mosquitoes are the main vectors for two pathogenic lineages of another arbovirus, West Nile virus (WNV), which are now endemic in southern Europe [6]. Mosquitoes and birds maintain the enzootic transmission cycle of WNV. Infected mosquitoes, however, may also feed on other vertebrates resulting in frequent infections in humans and horses [7]. In 1999, WNV was introduced in the United States. The outbreak that followed was characterized by high mortality rates in various American bird species and resulted in the largest outbreak of human neuroinvasive disease to date [8].

In Austria (2001), a sudden and substantial die-off occurred in Eurasian blackbirds (Turdus merula), closely resembling the 1999 WNV outbreak in the United States. Not WNV, but a related flavivirus (family Flaviviridae), Usutu virus (USUV), was identified in infected birds. This was the first isolation of USUV on the European continent [9]. The virus was first discovered in South Africa in 1959 and since then it has been identified in a number of African countries [10]. After the initial outbreak in Austria, USUV activity has been detected in birds from Spain, Italy, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, United Kingdom, Poland, Croatia, Germany and Belgium [11], [12]. In some southern European countries USUV co-circulates with WNV [13]. The high mortality in a large number of avian species enabled the spread of USUV to be monitored via the surveillance of dead birds [14]. Most of the USUV-positive bird species were blackbirds (T. merula), which belong to the same genus as the suspected WNV reservoir in the United States, the American robin (Turdus migratorius) [15]. USUV infected mosquitoes may also feed on other vertebrates, and the virus has been detected in horses [16] and bats [17]. Infections in humans have resulted in two diagnosed clinical cases in Africa [10]. In Europe, two Italian and three Croatian patients with neuroinvasive disease have been reported [18], [19], [20], attributed to USUV. However, serological evidence suggests that less severe and subclinical cases of human USUV infections occur regularly in endemic areas [21], [22], [23].

Similar to WNV, USUV is mostly transmitted by Culex mosquitoes. In Africa USUV has been isolated from Culex neavei, Culex perfuscus, Culex univitattus and Culex quinquefasciatus. Additionally, USUV has also been detected in a number of mosquito species from other genera [10]. Among European mosquito species, USUV is mostly found in the northern house mosquito (Culex pipiens), which is abundant throughout the northern hemisphere [13].

The presence of competent mosquitoes dictates the potential spread of arthropod-borne pathogens. Vectors are considered competent when they can transmit the pathogen from one vertebrate host to the next. Arboviruses, like USUV, are ingested by the mosquito via a blood meal of an infected vertebrate host, infect the epithelial cells that line the mosquito midgut, escape to the hemolymph, and finally accumulate in the saliva to be transmitted during the next blood meal [24]. Determining vector competence provides an insight into the viral transmission dynamics and is essential to assess the risk for future outbreaks. The only laboratory experiments with USUV were done with the African mosquito, C. neavei [25]. To better understand, predict, and assess the potential spread of USUV in Europe we investigated the vector competence of the northern house mosquito C. pipiens for USUV. In addition, we investigated the activity of RNA interference (RNAi), which is a major antiviral defense system of mosquitoes and other insects [34], [35]. The RNAi response against USUV has never been studied.

Here we show for the first time that C. pipiens is a highly effective European USUV vector. We provide an insight into the virus replication dynamics and the antiviral RNAi response within the mosquito vector and show how the vector competence of USUV relates to that of WNV at different temperatures.

Materials and methods

Cells and viruses

C6/36 cells were grown in Leibovitz L15 (Life Technologies, The Netherlands) medium, which was supplemented with 10% FBS. Vero E6 cells were cultured with DMEM Hepes (Life Technologies, The Netherlands)-buffered medium supplemented with 10% FBS containing penicillin (100 IU/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). When Vero E6 cells were infected with mosquito lysates or saliva the growth medium was supplemented with fungizone (2.5 μg/ml) and gentamycin (50 μg/ml). This medium will be referred to as fully supplemented medium. Passage 2 (P2) virus stocks of USUV, Bologna '09 (GenBank accession no. HM569263) [26] and WNV Gr'10 lineage 2 (GenBank accession no. HQ537483.1) [27], [28] were grown on C6/36 cells and titrated on Vero E6 cells.

Mosquito rearing

The European C. pipiens colony originated from Brummen, The Netherlands (°05′23.2″N 6°09′20.1″E) and was established in 2010 and maintained at 23 °C. The mosquito colony was kept in Bugdorm cages with a 16:8 light:dark (L:D) cycle and 60% relative humidity (RH), and provided with a 6% glucose solution as a food source. Bovine or chicken whole blood was provided through the Hemotek PS5 (Discovery Workshops, UK) for egg production. Egg rafts were allowed to hatch in tap water supplemented with Liquifry No. 1 (Interpet Ltd., UK). Larvae were fed with a 1:1:1 mixture of bovine liver powder, ground rabbit food and ground koi food.

In vivo infections

Two-to-five day old mosquitoes were infected either via ingestion of an infectious blood meal or via intrathoracic injections. Oral infections were performed by mixing whole chicken blood with the respective P2 virus stock to the indicated final concentration. Mosquitoes were allowed to membrane feed, using the Hemotek system, in a dark climate controlled room (24 °C, 70% RH) [29]. After 1 h, mosquitoes were sedated with 100% CO2 and the fully engorged females were selected. During intrathoracic injections the mosquitoes were sedated with CO2 by placing them on a semi-permeable pad, attached to 100% CO2. Mosquitoes were infected by intrathoracic injection using the Drummond nanoject 2 (Drummond Scientific Company, United States). Virus-exposed mosquitoes were incubated at the indicated temperatures with a 16:8 L:D cycle and fed with 6% sugar water during the course of the experiment.

Salivation assay

Transmission was determined using the forced salivation technique [29]. Briefly, mosquitoes were sedated with 100% CO2 and their legs and wings were removed. Their proboscis was inserted into a 200 μl filter tip containing 5 μl of salivation medium (50% FBS and 50% sugar water) W/V 50%). Mosquitoes were allowed to salivate for 45 min. Mosquito bodies were frozen in individual Eppendorf tubes containing 0.5 mm zirconium beads at − 80 °C. The mixture containing the saliva was added to 55 μl of fully supplemented growth medium.

Infectivity assays

Frozen mosquito bodies were homogenized in the bullet blender storm (Next Advance, United States) in 100 μl of fully supplemented medium and centrifuged for 90 s at 14,500 rpm in an Eppendorf Minispin Plus centrifuge (14,000 cf) inside the biosafety cabinet of the Wageningen biosafety level 3 laboratory. Thirty μl of the supernatant from the mosquito homogenate or the saliva-containing mixture was inoculated on a monolayer of Vero cells in a 96-well plate. After 2–4 h incubation the medium was replaced by 100 μl of fresh fully supplemented medium. Wells were scored for virus specific cytopathic effects (CPE) at three days post infection. Viral titers were determined using 10 μl of the supernatant from the mosquito homogenate in an end point dilution assay on Vero E6 cells. Infections were scored by CPE, three days post infection.

Analysis of small RNA libraries

Pools of twelve WNV or USUV infected mosquitoes were lysed in TRIzol (Life Technologies) reagent and total RNA was isolated. The isolation and sequencing of small RNAs were described previously [30]. In short, RNA was size separated by PAGE gel electrophoresis and small RNAs (19–33 nucleotides) were isolated. The small RNA library was prepared with the TruSeq Small RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 by Baseclear (www.baseclear.nl). FASTQ sequence reads were generated with the Illumina Casava pipeline (version 1.8.3) and initial quality assessment was performed by Baseclear using in-house scripts and the FASTQC quality control tool (version 0.10.0). FASTQ sequence reads that passed this quality control were analyzed with Galaxy [31]. Sequence reads were clipped from the adapter sequence (TruSeq 3′ adapter indexes #1 and #5) and mapped with Bowtie (version 1.1.2) [28] to the WNV (GenBank: HQ537483.1) and USUV (GenBank: HM569263.1) genomes. Size profiles of the viral small RNAs were obtained from all reads that mapped to their respective genomes with no more than one mismatch. The genome distribution of 21-nt viral small RNAs shows the number of 5′ ends at each nucleotide position of the viral genome. Read counts for the size profiles and genome distributions were normalized against the total library and are presented as a percentage of the library. Probing piRNAs for an overlap bias was performed using the Mississippi Galaxy Instance available from https://mississippi.snv.jussieu.fr/. The small RNA libraries were mapped to the WNV or USUV genomes using Bowtie2 and 25–30 nt reads were selected to calculate the overlap probability as described [32]. The nucleotide bias of the 25–30 nt viral small RNAs was determined using the Weblogo 3.3 tool available at the Galaxy main server.

Results

C. pipiens is a highly competent vector for USUV

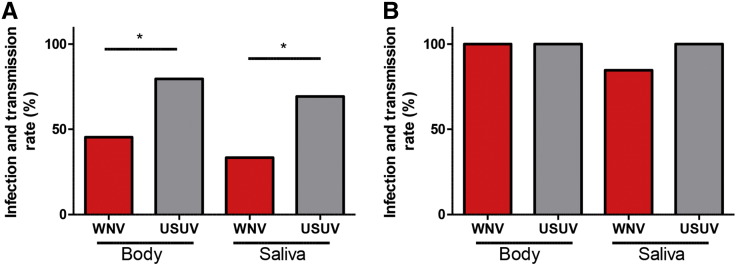

Recently we showed that C. pipiens from north-western Europe is a highly competent vector for pathogenic WNV isolates [29]. To evaluate vector competence of this mosquito for USUV, mosquitoes were offered a blood meal containing a 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of 4 ∗ 107 USUV or WNV per ml. The fully engorged females were maintained at 28 °C. Virus in the saliva of a mosquito is a prerequisite for transmission and therefore used as a proxy for transmission. We thus isolated saliva from individual mosquitoes at 14 dpi and detected infectious USUV or WNV particles by end-point dilution assays. The blood meal that contained WNV infected 46% of the mosquitoes, whereas the blood meal that contained USUV infected a significantly larger percentage (80%) of mosquitoes (Fig. 1A, Fisher's exact test, P < 0.05). From the mosquitoes that ingested a WNV-containing blood meal, 33% had infectious WNV in their saliva, whereas a USUV containing blood meal resulted in 69% of mosquitoes with infectious saliva (Fig. 1A, Fisher's exact test P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Culex pipiens is a highly competent vector for USUV. Mosquitoes were offered an infectious blood meal (A) or were injected (B) with either WNV or USUV. Fourteen days post infection mosquito saliva was collected and the mosquito body was homogenized in a cell culture medium. The mosquito homogenate and saliva were incubated on Vero E6 cells to detect the presence of either WNV or USUV in the mosquito bodies and saliva. Bars represent the percentage of positive samples. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.05).

To circumvent the midgut infection barrier [33], C. pipiens mosquitoes were inoculated intrathoracically with 5.5 ∗ 103 TCID50 of either virus, resulting in infection and transmission rates of both WNV and USUV up to 100% (Fig. 1B). Taken together, USUV not only infects a large percentage of C. pipiens mosquitoes but also effectively disseminates into their saliva. This indicates that these WNV-competent mosquitoes are even more effective as vector for USUV than WNV. In addition, the differential infectivity and transmissibility of both viruses after an infectious blood meal but not after intrathoracic injection suggests that the midgut epithelial cells play a differentiating role that determines vector competence.

USUV replication in the mosquito vector

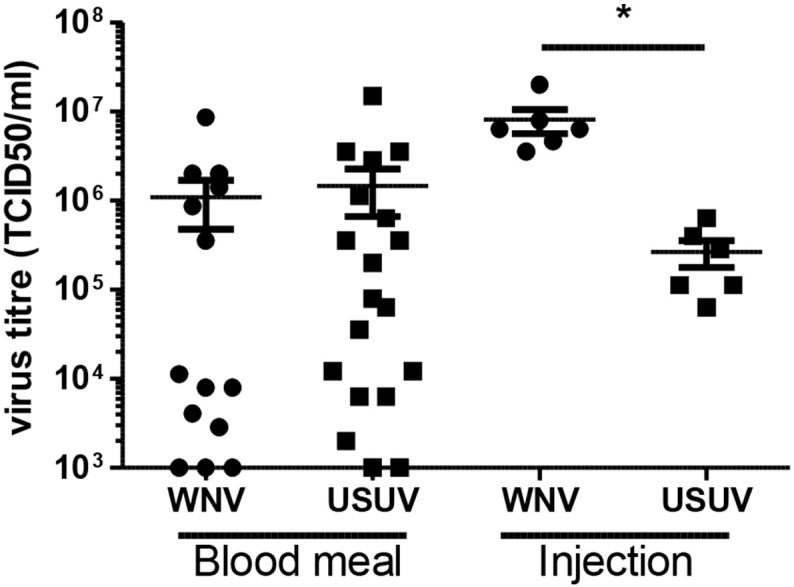

To investigate whether or not the increased dissemination of USUV relates to higher viral titers in the vector, the viral titers present in individual mosquito bodies were determined using end point dilution assays. Interestingly, mosquitoes that were orally infected with either WNV or USUV showed a similar variation in viral titers (Fig. 2, mean TCID50 of 1.1 ∗ 106 and 1.5 ∗ 106 per ml, respectively). In contrast, intrathoracic injection of either WNV or USUV resulted in significantly different viral titers, with a mean TCID50 of 8.1 ∗ 106 and 2.7 ∗ 105 per ml, respectively (Fig. 2, Student t-test, P < 0.05). In addition, USUV displayed viral titers that were 30 times lower compared with WNV, but without compromising dissemination to the salivary glands. This suggests that the bottleneck for vector competence is presented by the midgut epithelium, which differentially affects viral replication of WNV and USUV.

Fig. 2.

USUV and WNV replicate to equally high titers in Culex pipiens after an infectious blood meal but not after injection of the viruses. Homogenates from infected mosquitoes were used in end point dilution assays and the tissue culture infectious dose 50% (TCID50)/ml was determined. Data points represent individual mosquitoes infected with either USUV or WNV via the indicated route. Lines show the mean and whiskers the standard error of the mean. Asterisk indicates a significant difference (t-test, P < 0.05).

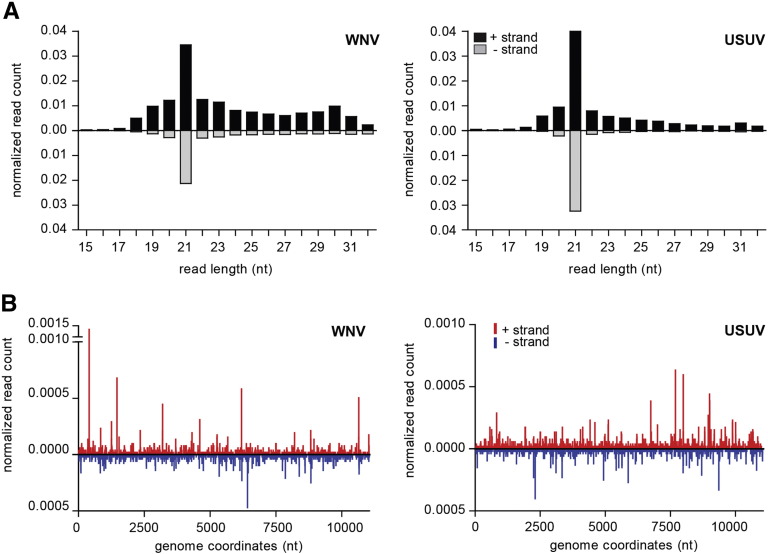

WNV and USUV produce viral siRNAs in infected C. pipiens

RNAi is activated by the recognition and cleavage of viral dsRNA into 21-nt small-interfering RNAs (siRNA) by the Dicer2 (DCR2) exo-ribonuclease [34], [35]. To investigate whether or not the RNAi pathway is activated by WNV and USUV infections in C. pipiens, small RNAs were isolated from pools of WNV or USUV infected mosquitoes and analyzed using deep-sequencing. For both viruses, viral small RNA populations are strongly biased for 21 nucleotide siRNAs (Fig. 3A), which map across the entire viral genome both on the viral sense and antisense strand (Fig. 3B). Recent reports have shown that a second class of small RNAs, known as viral PIWI-interacting RNAs (vpiRNAs), are produced in Aedes mosquitoes and mosquito cells in response to arbovirus infections. These small RNAs are 25–30 nt in size and, due to a specific amplification mechanism, known as the ping–pong loop, they can be distinguished by a characteristic sequence signature [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]. The RNAi response against USUV infection has never been studied. Probing the 25–30 nucleotides viral small RNAs for this signature, we were unable to identify vpiRNAs derived from either WNV or USUV (Supplemental Fig. S1) in Culex mosquitoes. Thus, the siRNA pathway is the major small RNA pathway that targets these two viruses in C. pipiens mosquitoes upon infection.

Fig. 3.

RNAi activity in WNV and USUV infected mosquitoes. (A) Size profile of the small RNAs mapping to the genome of WNV (left panel) or USUV (right panel). Reads mapping to the positive viral RNA strand (black) are shown above and reads mapping to the negative strand (gray) below the x-axes. (B) Genome distribution of 21 nucleotides vsiRNAs across the WNV (left panel) or USUV (right panel) genomes. Reads that map the positive strands are depicted in red, reads that map to the negative strands are depicted in blue. The number of small RNA reads in A and B was normalized against the total size of the library and is displayed as the percentage of the library.

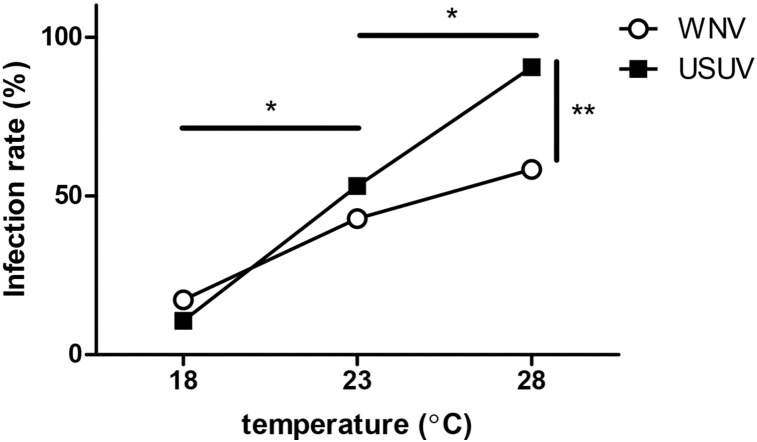

USUV infection is more effective at higher ambient temperatures

C. pipiens mosquitoes are more competent for WNV at higher ambient temperatures [29]. While both USUV and WNV are endemic in parts of Mediterranean Europe, USUV also extends its distribution into central and northwestern parts of Europe. We hypothesized that the ambient temperature could differentially affect the vector competence to either virus.

Oral infections were performed by offering the mosquitoes a blood meal containing either USUV or WNV, with 3.2 ∗ 107 and 2.2 ∗ 108 TCID50 per ml, respectively. We chose to use higher WNV titers to compensate for the lower vector competence for WNV (Fig. 1). Fully engorged females were incubated at three different temperatures (18 °C, 23 °C and 28 °C). These temperatures represent the mean diurnal summer (July–August) temperature in northwestern Europe, an intermediate temperature, and the mean diurnal summer temperature for Mediterranean Europe, respectively [41]. After two weeks the mosquitoes were homogenized and the respective viruses were detected. WNV displayed higher infection rates at higher temperatures, infecting 17% at 18 °C, 43% at 23 °C and 58% at 28 °C (Fig. 4, open symbols). At lower temperatures USUV infected a similar percentage of mosquitoes (11% at 18 °C and 53% at 23 °C). Interestingly, at 28 °C, 90% of the mosquitoes were infected with USUV (Fig. 4, closed symbols), which was significantly more as compared with the 58% for WNV (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.01). This was especially significant as the titer used for USUV in the infectious blood meals was seven times lower. This indicates that USUV is highly infectious for European C. pipiens mosquitoes and that temperature differentially affects the susceptibility of mosquitoes to either USUV or WNV.

Fig. 4.

r. After infectious blood meals, engorged mosquitoes were incubated at three different temperatures for fourteen days, before determining the presence of WNV and USUV. Data points indicate the percentage of infected mosquitoes from the total sample size (n > 25). Asterisks indicate significant differences between the temperatures (*P < 0.001, Fisher's exact test, for both WNV and USUV) and between WNV and USUV at 28 °C (**P < 0.01, Fisher's exact test).

Discussion

Here we show for the first time that USUV not only infects C. pipiens, but also effectively disseminates and accumulates in its saliva. In the field USUV is mostly detected in Culex species mosquitoes, although it has also been found in mosquitoes from four other genera within the family of Culicidae. To what extent mosquitoes from these genera may contribute to the dispersal of USUV is unclear. In southern Europe, USUV was detected in C. pipiens, which is the most abundant mosquito species in Europe and a competent WNV vector [10], [13], [29]. Northern Europe has a second abundant Culex species: Culex torrentium. It would be interesting to investigate whether this mosquito species can act as a transmission vector for USUV and if, to what extent.

In addition to competent USUV vectors, sufficient vertebrate species are required as amplifying hosts. Susceptible bird species are prevalent in Europe as USUV has been detected in a large number of avian species, most notably within the Turdus genus [9], [14]. In addition to birds, other vertebrates can become infected with USUV. Like WNV, humans and horses are incidental hosts. Whether bats develop viral titers that are high enough to contribute to the dispersal of USUV is unknown, but if this is a reservoir it could dramatically influence transmission model predictions [17]. Experimental WNV infections in birds can result in viremia above 109 plaque forming units per ml, which is sufficient to infect blood feeding mosquitoes [27], [42]. In the experiments presented here, the chicken blood used for infectious blood meals contained USUV titers of maximally 4 ∗ 107 TCID50 per ml. Higher titers in the blood of USUV infected birds may further increase the percentage of vectors able to transmit USUV after blood feeding.

Both USUV and WNV disseminated into the saliva of up to 100% of mosquitoes that were intrathoracically injected with either virus (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the viral titers that are present in orally infected mosquitoes were variable, whereas infection by injection displayed only a limited variation (Fig. 2). This suggests that the midgut acts as the major bottleneck for dissemination of the virus. Potentially, the induction of antiviral responses, and/or selective pressure for certain viral quasi species may influence subsequent viral replication and dissemination. Injection of WNV also resulted in titers that were higher than those of blood fed or USUV-injected mosquitoes. Together with the lower vector competence, this suggests that the barriers in the midgut epithelial cells of C. pipiens are more effective against WNV as compared with USUV.

Small RNA pathways are key to antiviral immunity in insects, including mosquitoes. In response to WNV infections, virus-derived siRNAs (vsiRNA) have been detected in C. quinquefasciatus [43]. We show that both WNV and USUV elicit a strong RNAi response by displaying the DCR2 dependent vsiRNAs of 21 nucleotides, which map to both the genomic positive RNA strand and the complementary negative strand. We did not identify vpiRNAs derived from WNV or USUV. These viral small RNAs have until now only been identified in Aedes mosquitoes, primarily for viruses of the Togaviridae and Bunyaviridae families [36], [37], [39], [40]. Yet, vpiRNA production from both dengue virus and cell fusing agent virus (both Flaviviridae) has been suggested to occur in RNAi-deficient cells [44]. The lack of vpiRNAs in the infection models presented here could therefore be attributed to an inability of Culex mosquitoes to process viral RNA into vpiRNAs or to flaviviral RNA being an inferior substrate for vpiRNA production. Thus, our data suggest that siRNA-mediated RNA interference is the major small RNA pathway targeting WNV and USUV in C. pipiens mosquitoes. Yet, there were no apparent differences in vsiRNA levels that could explain the differential transmission rates between the two viruses.

Despite the observed differences in infectivity and transmissibility, both WNV and USUV can effectively be transmitted by C. pipiens. However, their distribution throughout Europe only has a limited overlap. The dispersal of WNV has a strong correlation with mean summer temperatures, which can be explained by the vector competence for WNV at the corresponding temperatures [29]. USUV activity is also found in more temperate regions, but surprisingly the infectivity in C. pipiens showed a strong temperature dependency, which was more pronounced than for WNV. In the experiments presented here, we used a constant incubation temperature that represented a mean summer temperature. However, diurnal temperature fluctuations around this mean may have additional effects on the vector competence. Indeed, the vector competence of Ae. aegypti for dengue virus is influenced by the diurnal temperature range. Fluctuations around lower mean temperatures (< 18 °C) increased the vector competence in comparison with mosquitoes that were incubated at identical, yet constant, mean temperatures [45]. Because C. pipiens is more competent for USUV at higher temperatures, temperature fluctuations above a relatively low mean may still enable USUV to have a higher vectorial capacity compared with WNV, but this needs further experimental evidence. Other factors involved in transmission are e.g., population density of vectors and amplifying hosts (birds), mosquito survival and host feeding behavior of C. pipiens.

In conclusion, both USUV and WNV can be transmitted by European C. pipiens mosquitoes, with increased oral infection rates at higher temperatures. At higher temperatures, however, C. pipiens is significantly more competent for USUV than for WNV.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

WNV and USUV are not targeted by the piRNA pathway. Ping–pong amplification of vpiRNA causes a specific sequence signature [33], [36], [37]. Specifically, vpiRNAs derived from the opposite strands tend to show a 10-nt overlap. Furthermore, the antisense vpiRNAs usually start with uridine, whereas vpiRNAs from the sense strand have a bias for adenine at position 10. (A) Neither WNV (orange line) nor USUV (blue line) derived 25–30 nt small RNAs show an enrichment for 10 nt overlap. The overlap probability has been determined as specified [29], [43]. (B) Nucleotide biases for 25–30 nt viral small RNAs from the positive strand (upper panels) and negative strands (lower panels) for the indicated virus. Neither WNV (left panels) or USUV (right panels) have a strong nucleotide bias that would be indicative for Ping–pong amplification. n is the number of reads used to create the sequence logo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Corinne Geertsema and Els Roode for technical support concerning the BSL3 Laboratory. We would like to thank Christophe Antoniewski, the ARTbio bioinformatics analyses platform of the Institut de Biologie, Paris Seine and the http://mississippi.fr Galaxy server for sharing their bioinformatics tools. This work is supported by the European 195 Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7 VECTORIE project number 261466).

References

- 1.Paty M.C. Dengue fever in mainland France. Arch. Pediatr. 2014;21:1274–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rezza G., Nicoletti L., Angelini R., Romi R., Finarelli A.C., Panning M. Infection with chikungunya virus in Italy: an outbreak in a temperate region. Lancet. 2007;370:1840–1846. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61779-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grandadam M., Caro V., Plumet S., Thiberge J.M., Souares Y., Failloux A.B. Chikungunya virus, southeastern France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17:910–913. doi: 10.3201/eid1705.101873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delisle E., Rousseau C., Broche B., Leparc-Goffart I., L'Ambert G., Cochet A. Chikungunya outbreak in Montpellier, France, September to October 2014. Euro Surveill. 2015;20 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2015.20.17.21108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaffner F., Mathis A. Dengue and dengue vectors in the WHO European region: past, present, and scenarios for the future. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014;14:1271–1280. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70834-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magurano F., Remoli M.E., Baggieri M., Fortuna C., Marchi A., Fiorentini C. Circulation of West Nile virus lineages 1 and 2 during an outbreak in Italy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:E545–E547. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes E.B., Komar N., Nasci R.S., Montgomery S.P., O'Leary D.R., Campbell G.L. Epidemiology and transmission dynamics of West Nile virus disease. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:1167–1173. doi: 10.3201/eid1108.050289a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prevention CfDCa West Nile virus disease cases and deaths reported to CDC by year and clinical presentation, 1999–2013. Atlanta. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/ available at.

- 9.Weissenbock H., Kolodziejek J., Url A., Lussy H., Rebel-Bauder B., Nowotny N. Emergence of Usutu virus, an African mosquito-borne flavivirus of the Japanese encephalitis virus group, central Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002;8:652–656. doi: 10.3201/eid0807.020094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nikolay B., Diallo M., Boye C.S., Sall A.A. Usutu virus in Africa. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1417–1423. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0631. (Larchmont, NY) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vazquez A., Jimenez-Clavero M., Franco L., Donoso-Mantke O., Sambri V., Niedrig M. Usutu virus: potential risk of human disease in Europe. Euro Surveill. 2011;16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garigliany M.M., Marlier D., Tenner-Racz K., Eiden M., Cassart D., Gandar F. Detection of Usutu virus in a bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) and a great spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos major) in north-west Europe. Vet. J. 2014;199:191–193. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engler O., Savini G., Papa A., Figuerola J., Groschup M.H., Kampen H. European surveillance for West Nile virus in mosquito populations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2013;10:4869–4895. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10104869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chvala S., Bakonyi T., Bukovsky C., Meister T., Brugger K., Rubel F. Monitoring of Usutu virus activity and spread by using dead bird surveillance in Austria, 2003–2005. Vet. Microbiol. 2007;122:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilpatrick A.M., Daszak P., Jones M.J., Marra P.P., Kramer L.D. Host heterogeneity dominates West Nile virus transmission. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2006;273:2327–2333. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbic L., Vilibic-Cavlek T., Listes E., Stevanovic V., Gjenero-Margan I., Ljubin-Sternak S. Demonstration of Usutu virus antibodies in horses, Croatia. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:772–774. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2012.1236. (Larchmont, NY) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cadar D., Becker N., Campos Rde M., Borstler J., Jost H., Schmidt-Chanasit J. Usutu virus in bats, Germany, 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:1771–1773. doi: 10.3201/eid2010.140909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santini M., Vilibic-Cavlek T., Barsic B., Barbic L., Savic V., Stevanovic V. First cases of human Usutu virus neuroinvasive infection in Croatia, August–September 2013: clinical and laboratory features. Journal of Neurovirol. 2015;21:92–97. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0300-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavrini F., Gaibani P., Longo G., Pierro A.M., Rossini G., Bonilauri P. Usutu virus infection in a patient who underwent orthotropic liver transplantation, Italy, August–September 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pecorari M., Longo G., Gennari W., Grottola A., Sabbatini A., Tagliazucchi S. First human case of Usutu virus neuroinvasive infection, Italy, August–September 2009. Euro Surveill. 2009;14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takken W., Knols B.G. Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2007. Emerging Pests and Vector-borne Diseases in Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allering L., Jost H., Emmerich P., Gunther S., Lattwein E., Schmidt M. Detection of Usutu virus infection in a healthy blood donor from south-west Germany, 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaibani P., Pierro A., Alicino R., Rossini G., Cavrini F., Landini M.P. Detection of Usutu-virus-specific IgG in blood donors from northern Italy. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012;12:431–433. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2011.0813. (Larchmont, NY) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellor P.S. Replication of arboviruses in insect vectors. J. Comp. Pathol. 2000;123:231–247. doi: 10.1053/jcpa.2000.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikolay B., Diallo M., Faye O., Boye C.S., Sall A.A. Vector competence of Culex neavei (Diptera: Culicidae) for Usutu virus. Am.J.Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012;86:993–996. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaibani P., Cavrini F., Gould E.A., Rossini G., Pierro A., Landini M.P. Comparative genomic and phylogenetic analysis of the first Usutu virus isolate from a human patient presenting with neurological symptoms. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim S.M., Brault A.C., van Amerongen G., Bosco-Lauth A.M., Romo H., Sewbalaksing V.D. Susceptibility of carrion crows to experimental infection with lineage 1 and 2 West Nile viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:1357–1365. doi: 10.3201/eid2108.140714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papa A., Xanthopoulou K., Gewehr S., Mourelatos S. Detection of West Nile virus lineage 2 in mosquitoes during a human outbreak in Greece. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2011;17:1176–1180. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fros J.J., Geertsema C., Vogels C.B., Roosjen P.P., Failloyx A.B., Vlak J.M. West Nile virus: high transmission rate in north-western European mosquitoes indicates its epidemic potential and warrants increased surveillance. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Cleef K.W., van Mierlo J.T., Miesen P., Overheul G.J., Fros J.J., Schuster S. Mosquito and Drosophila entomobirna viruses suppress dsRNA- and siRNA-induced RNAi. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:8732–8744. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blankenberg D., Gordon A., Von Kuster G., Coraor N., Taylor J., Nekrutenko A. Manipulation of FASTQ data with Galaxy. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1783–1785. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brennecke J., Malone C.D., Aravin A.A., Sachidanandam R., Stark A., Hannon G.J. An epigenetic role for maternally inherited piRNAs in transposon silencing. Science. 2008;322:1387–1392. doi: 10.1126/science.1165171. (New York, NY) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forrester N.L., Coffey L.L., Weaver S.C. Arboviral bottlenecks and challenges to maintaining diversity and fitness during mosquito transmission. Virus. 2014;6:3991–4004. doi: 10.3390/v6103991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bronkhorst A.W., van Rij R.P. The long and short of antiviral defense: small RNA-based immunity in insects. Curr.t opinion virol. 2014;7:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blair C.D. Mosquito RNAi is the major innate immune pathway controlling arbovirus infection and transmission. Future Microbiol. 2011;6:265–277. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miesen P., Girardi E., van Rij R.P. Distinct sets of PIWI proteins produce arbovirus and transposon-derived piRNAs in Aedes aegypti mosquito cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6545–6556. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schnettler E., Donald C.L., Human S., Watson M., Siu R.W., McFarlane M. Knockdown of piRNA pathway proteins results in enhanced Semliki Forest virus production in mosquito cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2013;94:1680–1689. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.053850-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gammon D.B., Mello C.C. RNA interference-mediated antiviral defense in insects. Curr. opinion insect sci. 2015;8:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vodovar N., Bronkhorst A.W., van Cleef K.W., Miesen P., Blanc H., van Rij R.P. Arbovirus-derived piRNAs exhibit a ping–pong signature in mosquito cells. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morazzani E.M., Wiley M.R., Murreddu M.G., Adelman Z.N., Myles K.M. Production of virus-derived ping-pong-dependent piRNA-like small RNAs in the mosquito soma. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tank A.M.G.K., Wijngaard J.B., Konnen G.P., Bohm R., Demaree G., Gocheva A. Daily dataset of 20th-century surface air temperature and precipitation series for the European Climate Assessment. Int. J. Climatol. 2002;22:1441–1453. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Del Amo J., Llorente F., Perez-Ramirez E., Soriguer R.C., Figuerola J., Nowotny N. Experimental infection of house sparrows (Passer domesticus) with West Nile virus strains of lineages 1 and 2. Vet. Microbiol. 2014;172:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brackney D.E., Beane J.E., Ebel G.D. RNAi targeting of West Nile virus in mosquito midguts promotes virus diversification. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brackney D.E., Scott J.C., Sagawa F., Woodward J.E., Miller N.A., Schilkey F.D. C6/36 Aedes albopictus cells have a dysfunctional antiviral RNA interference response. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2010;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lambrechts L., Paaijmans K.P., Fansiri T., Carrington L.B., Kramer L.D., Thomas M.B. Impact of daily temperature fluctuations on dengue virus transmission by Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:7460–7465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101377108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

WNV and USUV are not targeted by the piRNA pathway. Ping–pong amplification of vpiRNA causes a specific sequence signature [33], [36], [37]. Specifically, vpiRNAs derived from the opposite strands tend to show a 10-nt overlap. Furthermore, the antisense vpiRNAs usually start with uridine, whereas vpiRNAs from the sense strand have a bias for adenine at position 10. (A) Neither WNV (orange line) nor USUV (blue line) derived 25–30 nt small RNAs show an enrichment for 10 nt overlap. The overlap probability has been determined as specified [29], [43]. (B) Nucleotide biases for 25–30 nt viral small RNAs from the positive strand (upper panels) and negative strands (lower panels) for the indicated virus. Neither WNV (left panels) or USUV (right panels) have a strong nucleotide bias that would be indicative for Ping–pong amplification. n is the number of reads used to create the sequence logo.