Abstract

To report a novel method using immobilized DNA within mesh to sequester drugs that have intrinsic DNA binding characteristics directly from flowing blood. DNA binding experiments were carried out in vitro with doxorubicin in saline (PBS solution), porcine serum, and porcine blood. Genomic DNA was used to identify the concentration of DNA that shows optimum binding clearance of doxorubicin from solution. Doxorubicin binding kinetics by DNA enclosed within porous mesh bags was evaluated. Flow model simulating blood flow in the inferior vena cava was used to determine in vitro binding kinetics between doxorubicin and DNA. The kinetics of doxorubicin binding to free DNA is dose-dependent and rapid, with 82–96 % decrease in drug concentration from physiologic solutions within 1 min of reaction time. DNA demonstrates faster binding kinetics by doxorubicin as compared to polystyrene resins that use an ion exchange mechanism. DNA contained within mesh yields an approximately 70 % decrease in doxorubicin concentration from solution within 5 min. In the IVC flow model, there is a 70 % drop in doxorubicin concentration at 60 min. A DNA-containing ChemoFilter device can rapidly clear clinical doses of doxorubicin from a flow model in simple and complex physiological solutions, thereby suggesting a novel approach to reduce the toxicity of DNA-binding drugs.

Keywords: Endovascular devices, Chemotherapy, Detoxification

1 Introduction

Intra-arterial treatment of solid organ primary tumors with chemotherapy and chemoembolization has improved outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (Curley et al. 1993, 1994; Fuhrman et al. 1994; Curley 1995; Forster et al. 2010; Jordan et al. 2010). A major limitation of intra-arterial treatment of HCC is that up to 50–70 % of doxorubicin infused in the hepatic artery either by direct infusion or administration of doxorubicin eluting beads (Lewis et al. 2006; Alexander et al. 2011, 2012), passes through the liver to the systemic circulation (Hwu et al. 1999) thus causing significant cardiac toxicity (Lipshultz et al. 2013). This limits the dose of doxorubicin that can be administered to HCC patients during each session of intra-arterial treatment (50–150 mg) and in aggregate over many treatment cycles (350 mg) (Llovet & Bruix 2003; Llovet et al. 2002; Marelli et al. 2007; Monier et al. 2016; Poon et al. 2007; Shin 2009). This method has the potential to prevent a variety of toxicities in the treatment of several cancers: for example, cardio-toxicity associated with treatment of HCC with doxorubicin and renal toxicity from treatment of head and neck cancer with cisplatin.

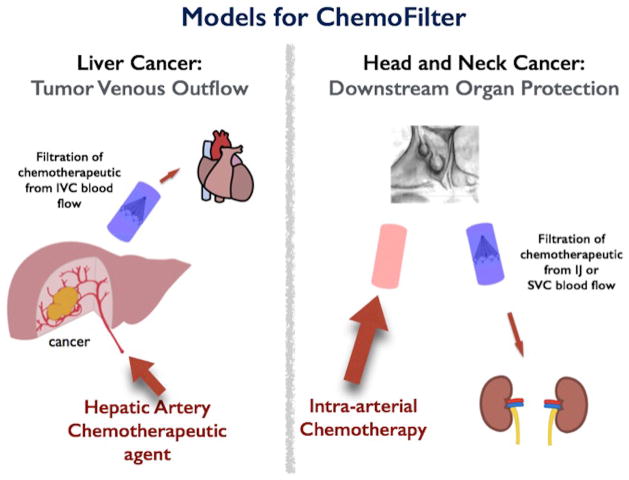

Endovascular filtration of drugs from the veins draining an organ receiving intra-arterial therapy is a novel approach to reduce the concentration of chemotherapeutics that bypass the tumor (Patel et al. 2014a, b), thus potentially reducing their side effects (Fig. 1). ChemoFilter is a temporarily deployable endovascular device that selectively binds a drug of interest when placed in the vein that provides the venous outflow from the tumor (Fig. 1). The first prototype ChemoFilter used ion exchange resins contained within porous “tea-bags” to remove doxorubicin from solution (Patel et al. 2014b). Doxorubicin is positively charged in vivo at physiologic pH and therefore has high affinity for anionic strong acid sulfonate groups (Patel et al. 2014b). A second prototype ChemoFilter uses magnetism to capture chemotherapeutics linked to iron oxide beads that are similar to magnetic targeted carrier bound to doxorubicin (MTC-DOX) (Mabray et al. 2016; Wilson et al. 2004).

Fig. 1.

Sample Clinical Deployment of ChemoFilter Devices. Schematic for deployment DNA ChemoFilter devices for intra-arterial chemotherapy delivery in liver cancer and head and neck cancer. Note that this concept can be applied to any primary solid organ tumor with an accessible venous outflow in which to temporarily deploy a filter device

In this manuscript we evaluate the feasibility of a third type of ChemoFilter, which will use DNA located in or on the ChemoFilter device to bind chemotherapeutics in flowing physiological solutions. This prototype selectively reduces the blood concentration of chemotherapeutics that have intrinsic DNA binding activity, such as doxorubicin which intercalates between the base pairs of DNA (Temperini et al. 2003). We hypothesize that immobilized genomic DNA can sequester treatment doses of doxorubicin (50 mg) from physiologic solutions such as saline, serum, and blood with rapid kinetics resulting in clearance of doxorubicin within minutes (Patel et al. 2014a, b).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 DNA-doxorubicin binding kinetics

A single chamber flow model using phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was utilized to determine the concentration of DNA needed to bind 0.05 mg/ml of Doxorubicin from solution, which estimates to a clinical dose of 50 mg in 1 l of solution. A doxorubicin dose of 50 mg was chosen because it is a clinical dose that is used for intra-arterial treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (Lammer et al. 2010). To determine clearance of supra-clinical doses of doxorubicin from solution, 0.1 mg/ml and 0.2 mg/ml concentrations of doxorubicin were used. To identify the optimum concentration of DNA, commercially available genomic DNA (salmon sperm genomic DNA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)—a standard laboratory reagent commonly used in molecular biology techniques—was selected and a range of concentrations of genomic DNA (0.04–1 mg/ml) was tested (Fig. 2). Reaction time points ranged from 1 min to 60 min and doxorubicin concentrations were plotted over time. Doxorubicin concentration was measured using absorbance spectrophotometry (Microplate Spectrophotometer; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at excitation wavelength 480 nm and emission 550 nm.

Fig. 2.

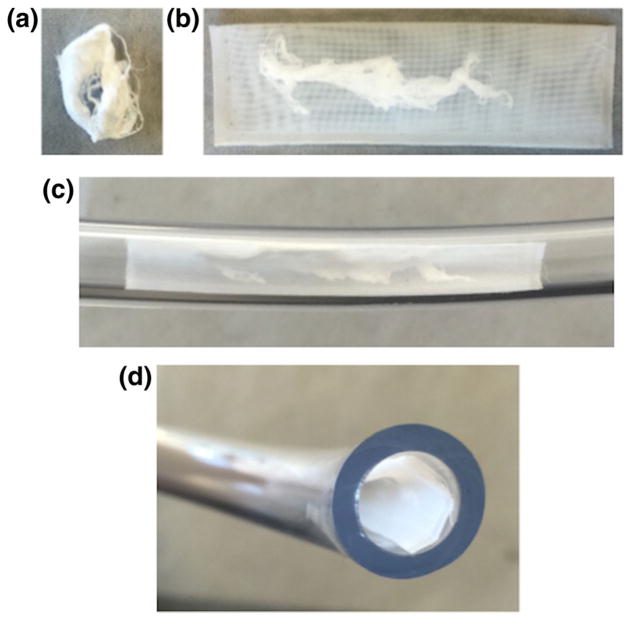

Prototype DNA ChemoFilter for in vitro testing. A. Genomic DNA in dehydrated form. B. Genomic DNA packaged into porous mesh with 160 μm pore size. C. Placement of packaged DNA into flow model tubing. D. Cross-sectional view of filter placement into flow model polyvinyl chloride tubing

The optimum DNA concentrations to clear therapeutic and supratherapeutic amounts of doxorubicin were initially determined in saline, which lacks the high protein concentrations of serum and blood and thus minimizes the competitive effect of protein interaction with doxorubicin. To measure the kinetics of doxorubicin clearance, genomic DNA was added to doxorubicin solution and time points from 1 min to 60 min were taken to measure residual doxorubicin concentration in solution.

After optimizing the DNA concentration that would clear doxorubicin, feasibility experiments were carried out in physiologically complex solutions, such as porcine serum (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and porcine blood (Sierra for Medical Science, Whittier, CA). For porcine blood experiments, an additional high speed centrifugation step (14,000 rpm) was added to the sample processing to remove red blood cells from solution and to measure doxorubicin in the residual serum. Kinetics of DNA-mediated filtration was compared to ion exchange resin Dowex, which also directly clears doxorubicin from solution, in side by side experiments performed on the same day. 0.19 g of Dowex resin 50Wx2 200–400 (Dowex, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was used for comparison studies.

2.2 DNA ChemoFilter device prototype

We packaged DNA into porous nylon or polyester mesh sacs in order to prevent large DNA fragments from diffusing out of the sacs, but still allow the small molecule doxorubicin to diffuse into the sacs (Fig. 2). Porous sacs were designed with dimensions such that they could be deployed through endovascular catheter-based delivery systems. Nylon meshes (Component Supply Co, Fort Meade, FL) with various pore sizes were used including 31 μm, 70 μm, 104 μm, 160 μm, 215 μm, and 255 μm. The pore size was initially selected relative to the size of standard ion exchange resin beads, which are typically 100–300 μm in diameter and, thus, could be constrained inside a sac with pores smaller than the bead diameter. Polyester mesh with pore size 160 μm (Component Supply Co, Fort Maede, FL) was chosen based on preliminary testing results demonstrating optimum clearance kinetics for this pore size (data not shown). Testing of DNA leakage from the packets was performed by measuring DNA concentration by UV spectroscopy at 260 nm wavelength. Doxorubicin clearance experiments as described above were performed with packaged DNA in PBS, porcine serum, and porcine blood.

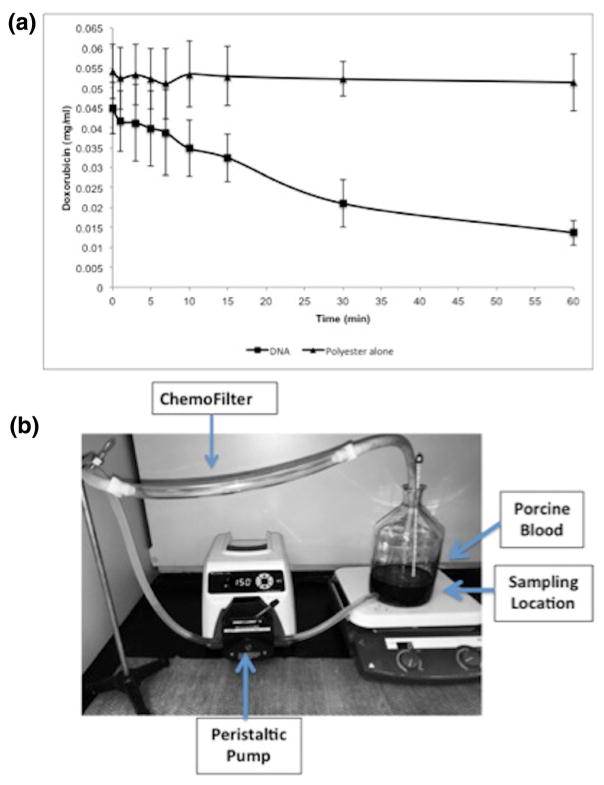

2.3 Feasibility testing using flow model

A closed-circuit flow model that simulates venous blood flow during hepatic intra-arterial chemotherapy delivery was used (Patel et al. 2014a, b). This model contains a single chamber and tubing that connected to a peristaltic pump (Masterflex, Vernon Hills, IL) shown in Fig. 7b. The peristaltic pump has controlled flow rate to match human hepatic blood flow (~750 ml/min). The polyvinyl chloride tubing matched the average human hepatic vein and internal jugular vein with filter segment measuring 1.2 cm in diameter and 6 cm in length. Testing was performed with 1 L PBS and porcine serum solutions and circulated for maximum of 60 min while samples were obtained. The 160 μm pore size polyester mesh filter device was introduced into the tubing within the flow circuit at time zero (Fig. 2). Nine samples were obtained after filter insertion to determine the kinetics of clearance of doxorubicin at the following times: 1 min, 3 min, 5 min, 7 min, 10 min, 15 min, 30 min, and 60 min. These time points were selected to evaluate the early and delayed clearance of drug.

Fig. 7.

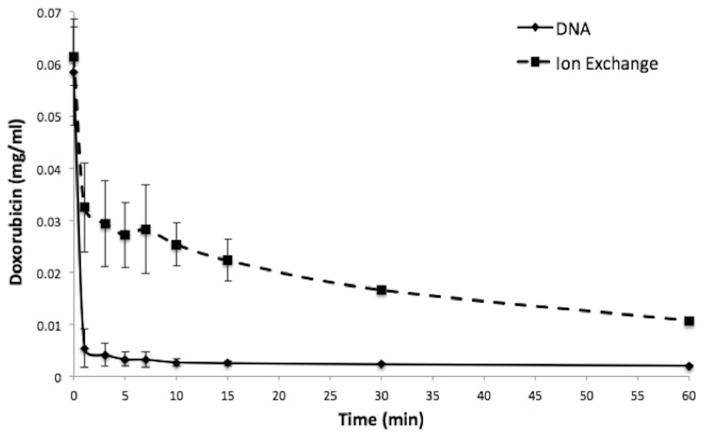

Comparison of DNA to ion exchange resin in porcine blood. DNA fragments have faster kinetics for clearance of doxorubicin than ion exchange resin in porcine whole blood. Plot shows decrease of doxorubicin concentration over 60 min in porcine blood. Data is presented as average ± SD, n = 3

2.4 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel (version 14.4.2) for Mac 2011 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). The mean and standard deviation were calculated for each time point and each trial number. We used paired samples t-test (IBM SPSS Statistics, version 23) to compare significance between the ion resin exchange and the DNA binding mechanism. We considered p < 0.05 statistically significant.

3 Results

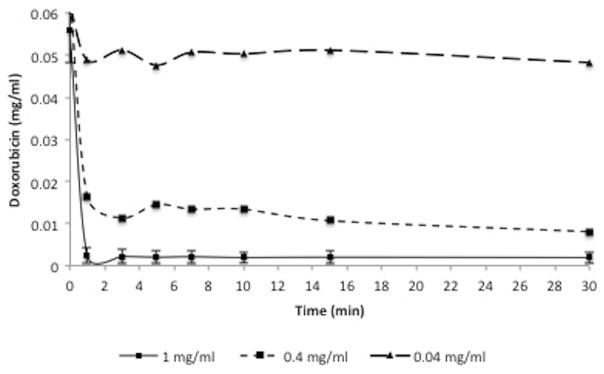

The concentration of DNA fragments required to clear doxorubicin from saline was dose dependent (Fig. 3). The kinetics of doxorubicin removal from solution by DNA (1 mg/ml) was rapid, with 95.1 % reduction in doxorubicin concentration within 1 min of reaction at room temperature (Fig. 4). Lower concentrations of DNA demonstrated decreased clearance of doxorubicin at 1 min (75.2 % clearance using 0.4 mg/ml DNA and 21 % clearance using 0.04 mg/ml DNA). Clearance curves demonstrated optimum removal of doxorubicin from solution within 1 min of reaction time with only minimal increased clearance at 30 min (95.1 % of doxorubicin removed at 1 min and 95.2 % removed within 30 min). For subsequent experiments, 1 mg/ml DNA concentration was utilized.

Fig. 3.

DNA ChemoFilter proof-of-concept experiments. Plot shows that DNA at concentration of 1 mg/ml in PBS solution filters 95.1 % of total dose of 50 mg of doxorubicin within 1 min of reaction time. Maximum clearance reached within 1 min of reaction time at 1 mg/ml concentration. Data for 1 mg/ml concentration are presented as average ± SD, n = 3

Fig. 4.

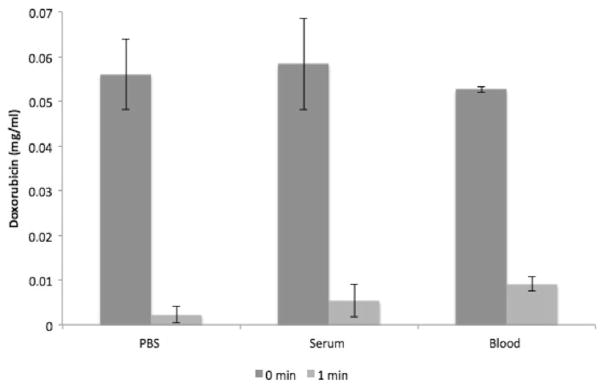

DNA is an effective binding agent for doxorubicin in vitro. Plot shows decrease of doxorubicin concentration within 1 min of reaction time in PBS, porcine serum, and porcine blood. Percent decrease is 96 %, 91 %, and 82 % respectively. Data is presented as average ± SD, n = 3

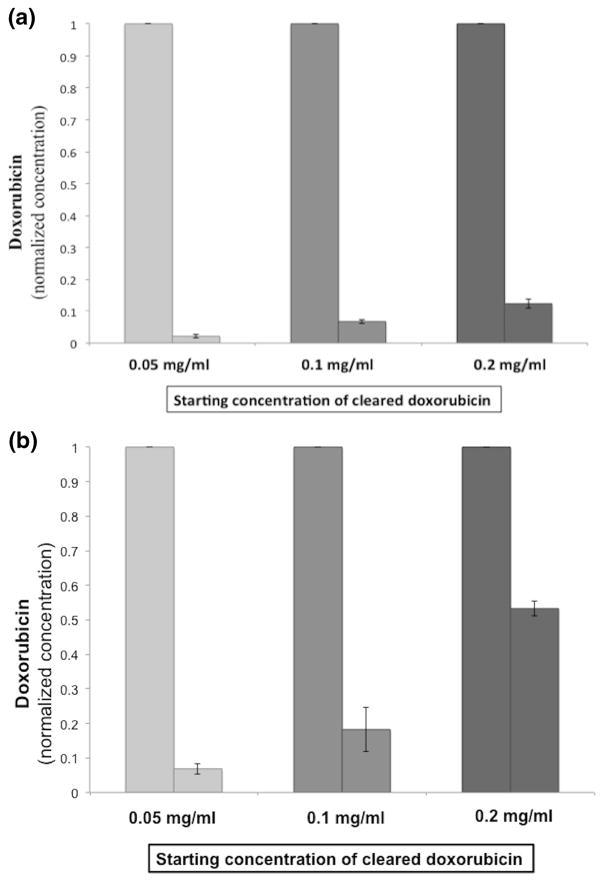

Effectiveness of genomic DNA to clear supra-therapeutic doses of doxorubicin was tested in PBS and porcine blood with serial doubling of doxorubicin concentration. At 5 min reaction time, there was 97.7 % and 93.1 % clearance for 0.05 mg/ml doxorubicin concentration in PBS and blood respectively. There was 93.3 % and 81.7 % clearance for 0.1 mg/ml doxorubicin concentration in PBS and blood respectively, and 87.7 % and 46.7 % clearance for 0.2 mg/ml doxorubicin concentration in PBS and blood respectively (Fig. 5). These concentrations correspond to 50 mg, 100 mg, and 200 mg of doxorubicin in 1 l of blood (Patel et al. 2014b).

Fig. 5.

Clearance of therapeutic and supra-therapeutic doses of doxorubicin by DNA over 5 min. Therapeutic and supra-therapeutic doses of doxorubicin are cleared with genomic DNA (1 mg/ml). A. Graph shows 97.7 %, 93.3 %, and 87.7 % clearance of doxorubicin from PBS solution within 5 min of reaction time. B. Graph shows 93.1 %, 81.7 %, and 46.7 % clearance of doxorubicin from porcine blood within 5 min of reaction time. Data is presented as normalized values as average ± SD, n = 3

Effectiveness of genomic DNA fragments to remove doxorubicin from solution was also tested in porcine serum and porcine whole blood. In porcine serum, there was 91 % decrease in doxorubicin concentration within solution within 1 min of reaction time (Fig. 4). In porcine blood, the decrease in doxorubicin concentration was slower: 82 % within 1 min (Figs. 4 and 7).

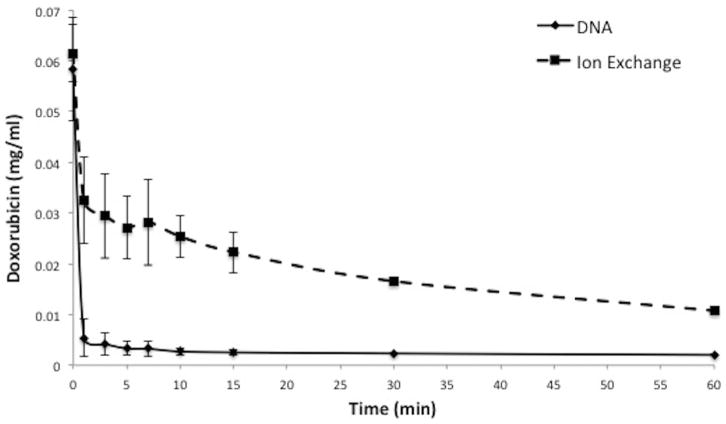

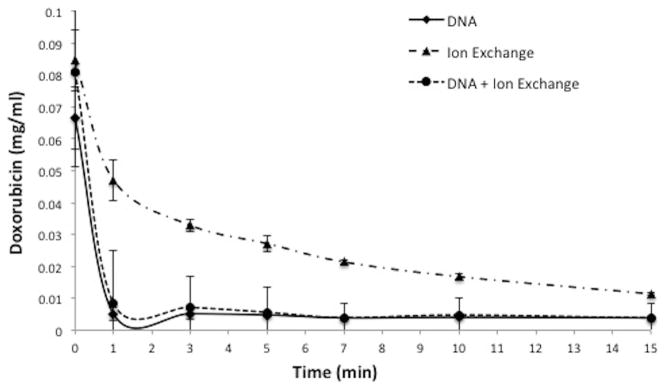

There is a difference in kinetics of doxorubicin clearance when comparing DNA fragments to the ion exchange based ChemoFilter that uses resin dowex (Patel et al. 2014a, b). Within 1 min of reaction time, DNA filtered 92.2 % of doxorubicin from porcine serum solution (Fig. 6) while ion exchange resin filtered 44.4 %. Comparison of DNA to ion exchange resin filtration demonstrates a statistically significant difference (Table 1) in binding of doxorubicin within the first 10 min of the reaction, with DNA resulting in more rapid and pronounced removal of doxorubicin from solution. Combining DNA fragments with ion exchange resin resulted in doxorubicin clearance kinetics that is identical to DNA fragments alone (Fig. 6). Similar findings were noted in porcine whole blood (Fig. 7), with 82.6 % of doxorubicin removed by DNA within 1 min of reaction time and 13.3 % by ion exchange resin.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of DNA to ion exchange resin in serum. DNA fragments have faster kinetics for clearance of doxorubicin than ion exchange resin. Plot shows decrease of doxorubicin concentration over 15 min in porcine serum. Data is presented as average ± SD, n = 3

Table 1.

Comparison of DNA to ion exchange resin. DNA fragments have faster kinetics than ion exchange resin. There is a statistically significant difference in doxorubicin concentration within the first 10 min between DNA and ion exchange resin (Dowex) in porcine serum based on t-test comparison of means. Values in parentheses indicate 95 % confidence intervals. Concentrations in this table are normalized to the original concentration

| Time (min) | DNA ChemoFilter | Ion Exchange ChemoFilter | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 1 | 0.0762 ± 0.0223 (0.0208–0.1315) | 0.5625 ± 0.1223 (0.2586–0.8663) | <0.05 |

| 3 | 0.0764 ± 0.0139 (0.0418–0.1109) | 0.3937 ± 0.0219 (0.3392–0.4481) | <0.05 |

| 5 | 0.0738 ± 0.0187 (0.5669–0.6171) | 0.3251 ± 0.0164 (0.2843–0.3658) | <0.05 |

| 7 | 0.0592 ± 0.0101 (0.0341–0.0842) | 0.2607 ± 0.0365 (0.1700–0.3513) | <0.05 |

| 10 | 0.0614 ± 0.0096 (0.0375–0.0852) | 0.2005 ± 0.0189 (0.1535–0.2474) | <0.05 |

| 15 | 0.0590 ± 0.0080 (0.0391–0.0788) | 0.2300 ± 0.0747 (0.0444–0.4155) | <0.05 |

In porcine blood, there was a 96.5 % decrease in doxorubicin concentration by DNA packaged in polyester mesh sac (160 μm pore size) within 1 min of reaction (Fig. 8). DNA leakage from the polyester packet (160 μm pore size) was determined by measuring the amount of DNA in solution outside of the packet. Only 0.5 % of DNA was found to have leaked from the packet by 30 min.

Fig. 8.

DNA ChemoFilter prototype testing in blood. DNA fragments in polyester packets with 160 μm pore size effectively clears doxorubicin from solution in porcine whole blood. Data is presented as average ± SD, n = 3

A closed circuit in vitro flow model was used to determine if DNA effectively reduces doxorubicin concentration from solution under physiologic conditions (Fig. 9). There was a 69 % drop in doxorubicin concentration within porcine serum at 1 h (Fig. 9a). Polyester mesh alone did not demonstrate a reduction in doxorubicin concentration over time within the flow model.

Fig. 9.

DNA ChemoFilter prototype testing in flow model. A. DNA fragments in polyester packets within the flow model using porcine serum. There is progressive decrease in doxorubicin concentration from solution over time. B. Closed loop flow model used for the experiments

4 Discussion

We demonstrated the concept of using fragments of genomic DNA—both free in solution and contained in porous sacs—to selectively filter a drug with intrinsic DNA affinity from solution and using physiologic flow model. Our titration experiments confirmed that genomic DNA fragments remove clinically-relevant doses of doxorubicin from solution in a concentration-dependent manner in physiologic conditions. We also showed that DNA can clear supra-therapeutic doses of doxorubicin, thus potentially being effective for future use in concert with higher doses of doxorubicin to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. DNA results in more rapid and pronounced removal of doxorubicin from solution as compared to ion exchange resins (p < 0.05). Our results agree with published maximum doxorubicin clearance of 92 % from saline by 30 min of reaction time (Patel et al. 2014b). These characteristics underscore a potential advantage for a DNA-mediated ChemoFilter over an ion exchange mediated design: reducing drug concentration through the filter device and resulting in an even lower amount of chemotherapeutic reaching sensitive organs such as the heart and kidneys.

Looking forward to clinical translation of this technology, the potential kinetic advantages of a DNA-mediated ChemoFilter must be weighed against the potential risks of introducing a DNA-containing device into a patient’s venous bloodstream even if for only minutes to hours during and immediately following loco-regional intra-arterial drug infusion. The experiments presented in this manuscript used DNA contained within porous sacs for ease of manufacture. Future versions of this device will include smaller DNA fragments (oligonucleotides) immobilized to solid supports that should be less likely to leak into the blood. As the immunogenic consequences of DNA fragment leakage from a device like this into the blood are unknown, DNA-based devices will require more extensive in vivo testing than simpler devices made of relatively biologically inert materials.

Our study has limitations due to its nature as an in vitro proof-of-concept design. In vivo feasibility studies will need to be performed to determine efficacy of using DNA to reduce doxorubicin concentration within the inferior vena cava or other veins in animal models. In addition, our design currently uses the non-optimized “tea-bag” model, which has limited surface area for DNA to interact with flowing solution. In the future, we plan to increase the surface area for DNA interaction with solution by immobilizing DNA on membranes or other micro-engineered materials as opposed to sequestering DNA within a “tea-bag” made of inert material. Another limitation of our device is that it contains freely floating large DNA fragments, which could leak small DNA fragments into solution (as has already been seen in vitro). This phenomenon may be more pronounced in vivo, with DNAses and other components of the blood leading to increased fragmentation of DNA. Immobilization of DNA is expected to reduce leakage of DNA fragments from the filter device into the blood stream. As discussed above, we plan to decrease the leakage by immobilizing DNA to beads, membranes, or other engineered surfaces.

Potential locations for placement of DNA ChemoFilter under image guidance include suprahepatic inferior vena cava for hepatocellular cancer and internal jugular vein for head and neck cancer (Fig. 1). For HCC, ChemoFilter can be deployed in the hepatic veins or suprahepatic IVC (Fig. 1), thus reducing the concentration of cardiotoxic doxorubicin reaching the heart. For head and neck cancer, ChemoFilter could be placed in the internal jugular veins or superior vena cava, thereby reducing the amount of nephrotoxic cisplatin reaching the kidneys.

In conclusion, we used genomic DNA contained in an endovascular medical device to selectively reduce therapeutic and supratherapeutic concentrations of a DNA-binding drug in saline, serum, and blood. DNA effectively filters a high percentage of doxorubicin within 1 min, thus making it an efficient mechanism to clear doxorubicin in clinically relevant time-frame.

Acknowledgments

The work presented was supported by NIH grants 1R01CA194533 (Steven Hetts, PI; UCSF), 1R41CA183327 (Anand Patel, PI; ChemoFilter, Inc.), and training grant 5T32EB001631 (Thomas Link, PI) to the University of California San Francisco Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging (Mariam Aboain; UCSF T32 fellow). A patent underlying the ChemoFilter technology was licensed to ChemoFilter, Inc, by the University of California; that license was subsequently incorporated in the acquisition of ChemoFilter, Inc by Penumbra, Inc (Alameda, California). ChemoFilter is a trademark of Penumbra, Inc.

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at RSNA 2015 annual meeting in the “Interventional series: complications in interventional oncology – avoidance and damage control” session and at the NIH 8th Image Guided Workshop in 2016.

This work represents original research and there is no overlap with previously published research.

References

- Alexander CM, Maye MM, Dabrowiak JC. DNA-capped nanoparticles designed for doxorubicin drug delivery. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47:3418–3420. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04916f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander CM, Dabrowiak JC, Maye MM. Investigation of the drug binding properties and cytotoxicity of DNA-capped nanoparticles designed as delivery vehicles for the anticancer agents doxorubicin and actinomycin D. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:2061–2070. doi: 10.1021/bc3002634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley SA. Treatment of liver cancers with complete hepatic venous isolation and extracorporeal chemofiltration. Surgery. 1995;117:718–719. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(95)80020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley SA, et al. Reduction of systemic drug exposure after hepatic arterial infusion of doxorubicin with complete hepatic venous isolation and extracorporeal chemofiltration. Surgery. 1993;114:579–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley SA, et al. Complete hepatic venous isolation and extracorporeal chemofiltration as treatment for human hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase I study. Ann Surg Oncol. 1994;1:389–399. doi: 10.1007/BF02303811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster RE, et al. Comparison of DC Bead-irinotecan and DC Bead-topotecan drug eluting beads for use in locoregional drug delivery to treat pancreatic cancer. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2010;21:2683–2690. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4107-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman GM, et al. Hepatic arterial infusion of verapamil and doxorubicin with complete hepatic venous isolation and extracorporeal chemofiltration: pharmacological evaluation of reduction in systemic drug exposure and assessment of hepatic toxicity. Surg Oncol. 1994;3:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0960-7404(94)90020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwu WJ, et al. A clinical-pharmacological evaluation of percutaneous isolated hepatic infusion of doxorubicin in patients with unresectable liver tumors. Oncol Res. 1999;11:529–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan O, Denys A, De Baere T, Boulens N, Doelker E. Comparative study of chemoembolization loadable beads: in vitro drug release and physical properties of DC bead and hepasphere loaded with doxorubicin and irinotecan. J Vasc Int Radiol: JVIR. 2010;21:1084–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammer J, et al. Prospective randomized study of doxorubicin-eluting-bead embolization in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: results of the PRECISION V study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AL, et al. Pharmacokinetic and safety study of doxorubicin-eluting beads in a porcine model of hepatic arterial embolization. J Vasc Int Radiol: JVIR. 2006;17:1335–1343. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000228416.21560.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshultz SE, Cochran TR, Franco VI, Miller TL. Treatment-related cardiotoxicity in survivors of childhood cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:697–710. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabray MC, et al. In Vitro Capture of Small Ferrous Particles with a Magnetic Filtration Device Designed for Intravascular Use with Intraarterial Chemotherapy: Proof-of-Concept Study. J Vasc Int Radiol: JVIR. 2016;27(3):426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelli L, et al. Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:6–25. doi: 10.1007/s00270-006-0062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monier A, et al. Liver and biliary damages following transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison between drug-eluting beads and lipiodol emulsion. Eur Radiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4488-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, et al. O-016 development and validation of an endovascular chemotherapy filter device for removing high-dose Doxorubicin from the blood: in vivo porcine study. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014a;6(Suppl 1):A9. doi: 10.1115/1.4027444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AS, et al. Development and validation of endovascular chemotherapy filter device for removing high-dose doxorubicin: preclinical study. J Med Device. 2014b;8:0410081–0410088. doi: 10.1115/1.4027444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon RT, et al. A phase I/II trial of chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel intra-arterial drug-eluting bead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol: Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2007;5:1100–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SW. The current practice of transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:425–434. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.5.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temperini C, et al. The crystal structure of the complex between a disaccharide anthracycline and the DNA hexamer d(CGATCG) reveals two different binding sites involving two DNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:1464–1469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MW, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: regional therapy with a magnetic targeted carrier bound to doxorubicin in a dual MR imaging/conventional angiography suite–initial experience with four patients. Radiology. 2004;230:287–293. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2301021493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]