Abstract

In the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei, the large rRNA, which is a single 3.4- to 5-kb species in most organisms, is further processed to form six distinct RNAs, two larger than 1 kb (LSU1 and LSU2) and four smaller than 220 bp. The small rRNA SR1 separates the two large RNAs, while the remaining small RNAs are clustered at the 3′ end of the precursor rRNA. One would predict that T. brucei possesses specific components to carry out these added processing events. We show here that the trypanosomatid-specific nucleolar phosphoprotein NOPP44/46 is involved in this further processing. Cells depleted of NOPP44/46 by RNA interference had a severe growth defect and demonstrated a defect in large-ribosomal-subunit biogenesis. Concurrent with this defect, a significant decrease in processing intermediates, particularly for SR1, was seen. In addition, we saw an accumulation of aberrant processing intermediates caused by cleavage within either LSU1 or LSU2. Though it is required for large-subunit biogenesis, we show that NOPP44/46 is not incorporated into the nascent particle. Thus, NOPP44/46 is an unusual protein in that it is both nonconserved and required for ribosome biogenesis.

Ribosome biogenesis is a highly conserved process. The conservation is seen not only in the proteins and RNAs that make up the mature ribosome but also in the accessory proteins involved in its biogenesis. In eukaryotes, the initial steps take place in the nucleolus, where RNA polymerase I transcribes the rRNA precursor. The RNA is then processed in a characteristic pathway, while the ribosomal proteins and the 5S RNA are incorporated into the maturing ribosomal subunits. As biogenesis continues, the small subunit is exported to the cytoplasm, where maturation is completed to form the 40S subunit (14, 27). Meanwhile, the large-subunit precursor, in a ∼66S particle, undergoes a number of processing events, first within the nucleolus and then within the nucleus, including the incorporation of 5S rRNA. It is eventually exported to the cytoplasm, where it reaches maturation as the 60S subunit (12).

In the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei, the overall framework of this pathway is conserved (10). This parasite, which causes African sleeping sickness in humans and wasting diseases in economically important domestic livestock, is related to other trypanosomatid pathogens, including Trypanosoma cruzi (the causative agent of Chagas' disease) and Leishmania species (causative agents of leishmaniasis). In T. brucei, as in other organisms, one of the earliest cleavage events after transcription is the separation of the small-subunit 18S rRNA precursor from the large-subunit precursor rRNAs. As in other eukaryotes, the large-subunit precursor rRNA is then processed to separate from the 5.8S rRNA. Putative orthologues of a number of ribosome biogenesis proteins have been annotated in the T. brucei genome sequence, and at least one biogenesis-specific protein (NOG1) has been shown to be functionally conserved (13, 19). Despite the conservation of these steps and proteins, there are key differences. The most notable difference is that the 25S (large-subunit) rRNA is further processed into six structural RNA species, including two large RNAs (1,500 to 1,900 nucleotides in size) and four small RNAs (77 to 215 nucleotides) (28).

Given the unusual processing of the large-subunit rRNA and the evolutionary distance between T. brucei and the other eukaryotes for which ribosome biogenesis has been studied (principally Saccharomyces cerevisiae and mammals), one would expect to find some novel components in the parasite. One potential novel component is the nucleolar phosphoprotein NOPP44/46. NOPP44/46 was initially identified as having developmentally regulated tyrosine phosphorylation. It is heavily tyrosine phosphorylated in the procyclic insect stage and in the nondividing mammalian intermediate and stumpy bloodstream forms but not in the proliferative mammalian slender bloodstream form (21). In addition, the abundance of the protein is also developmentally regulated, with three- to fourfold-higher levels in stumpy and procyclic forms than in the slender bloodstream form (21). Yeast two-hybrid analysis and coimmunoprecipitation from trypanosome lysates demonstrated that NOPP44/46 associates with NOG1 and the protein kinase CK2 (previously known as casein kinase II) (18).

The NOPP44/46 protein consists of a series of four domains. The first domain (U) consists of the first 96 amino acids and has modest homology to domains found in some other nucleolar proteins, including nucleolar histone deacetylase and FK506 binding protein. The next domain (J) consists of 43% aspartic acid and glutamic acid residues, while the third domain (A) consists almost exclusively (78%) of acidic residues. The final domain (R) contains a series of Arg-Gly-Gly (RGG) repeats that enable the protein to bind nucleic acids (5, 6). RGG repeats are found in certain proteins required for ribosome biogenesis, such as fibrillarin (NOP1) and GAR1 (2, 8). Multiple NOPP44/46 isoforms are visible upon immunoblotting specific monoclonal antibodies, resulting from differing numbers of RGG repeats (6) and possibly variations in the number of acidic residues in the A region.

Here we report that NOPP44/46 is a trypanosomatid-specific protein involved in ribosome biogenesis. Knockdown of the endogenous mRNA by RNA interference (RNAi) led to growth arrest accompanied by a severe large-ribosomal-subunit biogenesis defect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

All of the work described uses the procyclic T. brucei strain 29-13 (29), which expresses both T7 RNA polymerase and the tetracycline (TET) repressor, allowing for TET-regulated expression of introduced genes. Cells were grown in SDM-79 (JRH Biosciences) plus 15% fetal calf serum and also containing 15 μg of G418/ml and 50 μg of hygromycin/ml to maintain the T7 RNA polymerase and TET repressor constructs. Transfections were performed as described previously (1), and stable transfectants were selected by using 2.5 μg of phleomycin/ml. Clonal isolates A6 and C11 were derived by limiting dilution of 29-13 cells stably transfected with pZJM-NOPP44/46. TET-regulated constructs were induced with 1 to 2 μg of TET/ml.

Plasmids.

To construct the pZJM-NOPP44/46, plasmid DNA from pTbmyc2-UJA (5) was used as a PCR template to amplify the U and J regions with a 5′ sense primer (AAGCTTATAAATTACTTCCAATCGGCAGCAATGG) and a 3′ antisense primer (ATGCTCTCGAGTTACGCGTCAATTCCTTCATTGT). The PCR fragment was ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The HindIII-XhoI fragment (sites italicized in the primer sequences) was excised and ligated into the vector pZJM (17).

A portion of the coding region corresponding to the Tb08.12O16.320 gene, a NOPP44/46-related gene, was PCR amplified from 29-13 genomic DNA with a 5′ sense primer (GTGGTGAGATTTGCAGTGGTGTC) and a 3′ antisense primer (AACTGATCCGCTTCATGGATTG) by using Expand High Fidelity Taq polymerase (Roche). The resulting fragment was ligated into pGEM-T Easy.

RNA isolation and Northern analysis.

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol (Invitrogen). For Northern analysis, 5 μg of total RNA was loaded per lane on a formaldehyde agarose gel and transferred to NytranN nylon membranes (Schleicher and Schuell). Membranes were hybridized with either an RNA probe (NOPP44/46, Tb08.12O16.320, international transcribed spacer 1 [ITS1], and ITS2) or end-labeled oligomers (ITS3 and ITS7). The ITS3 and ITS7 oligomers have been described previously (13). Membranes were hybridized in either ULTRAhyb or ULTRAhyb-Oligo (Ambion) and washed with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (oligonucleotide probes) at 42°C or 2× SSC-0.1% SDS followed by 0.1× SSC-0.1% SDS (RNA probes) at 65°C. Signals were quantitated on a phosphorimager.

Western analysis.

Proteins were separated on SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose. Membranes were hybridized with antisera or antibodies followed by horseradish peroxidase conjugated to either protein A (ICN) or goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Perkin Elmer). Anti-NOPP44/46 monoclonal antibody ID2 (21) was used at 100 ng/ml, while anti-NOG1 629L (19) was used at either 1:500 for analysis of sucrose density gradients or 1:5,000 for total cell lysates. Anti-phosphoglycerate kinase (anti-PGK) (20) was used at 1:2,000, and anti-p34/p37 (31) was used at 1:800. Secondary antibodies were detected by Western lighting (Perkin Elmer).

Polysome analysis.

Lysates from 109 cells were prepared for polysome analysis as described previously (3) and modified (13). Lysate from 4 × 108 cells was layered onto a 12-ml, 10 to 40% sucrose gradient containing 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 300 mM KCl, and 10 mM MgCl2. Gradients were centrifuged for 2 h at 230,000 × g in an SW40 rotor (Beckman) and collected by using an ISCO model 185 density gradient fractionator with RNA absorbance monitored at 254 nm.

RESULTS

NOPP44/46 is essential for proliferation of T. brucei procyclic forms.

The localization of NOPP44/46 to the nucleolus and its interaction with NOG1, a protein required for biogenesis of the large ribosomal subunit, led to the hypothesis that NOPP44/46 is involved in ribosome biogenesis. The genomic region containing NOPP44/46 as depicted on GeneDB (www.genedb.org) is ambiguous due to a number of repeats and hence does not provide a clear picture of the gene copy number. However, earlier data suggested that NOPP44/46 is part of a multigene family with approximately four genes per diploid genome (6). We therefore used RNAi to reduce the mRNA abundance rather than trying to generate a regulated gene knockout. A fragment containing both the U and J domains common to all genes was placed into the vector pZJM. This vector contains convergent TET-inducible T7 promoters that enable the production of double-stranded RNA corresponding to any DNA inserted between them. The double-stranded RNA is processed and targets the complementary mRNA for degradation. Plasmid pZJM-NOPP44/46 was transfected into the procyclic T. brucei strain 29-13 that is engineered for TET-inducible expression from T7 promoters.

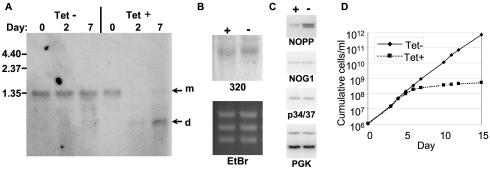

Stable transfectants were isolated and tested for knockdown of the endogenous NOPP44/46 mRNA. Upon induction with TET, only a moderate decrease in the level of mRNA was seen (data not shown). In the hope of generating a stronger phenotype, we cloned the transfectant line by limiting dilution. Two clonal lines that had a much more significant reduction in NOPP44/46 mRNA upon induction of RNAi (many other lines did not show a strong effect) were isolated. Northern analysis of one of the clones demonstrated that the NOPP44/46 mRNA had decreased more than 10-fold after 2 days and that this reduction was maintained in samples taken after 7 days (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

NOPP44/46 is required for parasite proliferation. (A) Northern analysis of NOPP44/46 RNAi. RNA was isolated from either induced (TET+) or uninduced (TET−) procyclic 29-13 cells transfected with pZJM-NOPP44/46 (clone C11) on the specified day after the addition of TET. Isolated RNA was run on a gel and blotted and hybridized with a riboprobe directed against the U and J regions of NOPP44/46. The upper arrow (m) denotes the NOPP44/46 mRNA, and the lower arrow (d) denotes the double-stranded RNA produced upon induction of pZJM-NOPP44/46. Molecular size markers are shown in kilobases. (B) Northern analysis of NOPP44/46 RNAi to determine its effect on Tb08.12O16.320 expression. The RNA from day 7 cells (clone A6), induced (+) and uninduced (−), was blotted and hybridized with a probe specific to the related gene Tb08.12O16.320. The ethidium bromide-stained gel (EtBr) verifies equal loading. (C) Western analysis of NOPP44/46 RNAi. Total cell lysates from clone A6, either induced (+) or uninduced (−), were prepared 7 days after induction. Cell equivalents were then loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel and blotted. Blots were probed with antibodies against NOPP44/46 (NOPP), NOG1, p34/p37, or PGK. The upper band in PGK is the 56-kDa glycosomal isoform, while the bottom band is the 45-kDa cytosolic isoform. (D) Growth curve of NOPP44/46 RNAi cells. Cells from either induced (dashed line) or uninduced (solid line) clone A6 were counted, and the cumulative cell numbers were plotted.

Analysis of the recently completed genome sequence for T. brucei revealed a NOPP44/46-related gene, the Tb08.12016.320 gene, which encodes a predicted protein with U- and R-related domains (but not J and A domains). The first 333 nucleotides of this gene show a significant level of identity (75%) to the NOPP44/46 gene. We therefore tested whether the induction of NOPP44/46 RNAi affected the expression of this related mRNA. Hybridization of RNA from induced and uninduced day 7 NOPP44/46 RNAi cells demonstrated that the abundance of Tb08.12O16.320 mRNA was unaffected (Fig. 1B).

To determine the effect of RNAi on protein expression, cell lysates were prepared 7 days after induction. NOPP44/46 levels dropped approximately sevenfold compared to those of uninduced lysates (Fig. 1C). At the same time, the level of the NOPP44/46-associated protein NOG1 decreased slightly. Since NOG1 levels decrease as cells enter stationary phase (A. Randall, unpublished data), it is not clear if NOG1 levels are directly affected by the decrease in NOPP44/46 or are responding to a change in growth rate (Fig. 1D). Another NOPP44/46-associated protein, p34/p37, and the two isoforms of the glycolytic enzyme PGK were unchanged upon NOPP44/46 depletion.

The growth of cells depleted of NOPP44/46 was monitored. Commensurate with the drops in RNA and protein, the proliferation of the induced strains dropped dramatically at day 5 (Fig. 1D). Despite the lack of proliferation, the cells appeared to be relatively healthy throughout this period. These data demonstrate that NOPP44/46 is required for cell growth.

NOPP44/46 RNAi leads to a defect in large-subunit biogenesis.

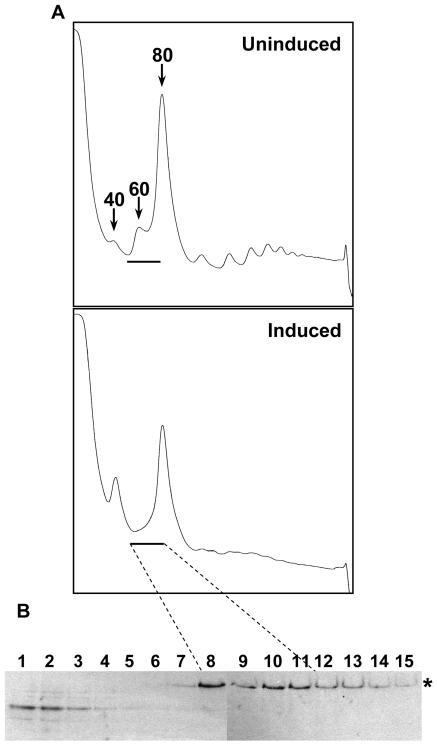

To determine the effect of depletion of NOPP44/46 on ribosome biogenesis, the ribosomal content of the cells was assessed by analytical sucrose gradient analysis. Cells were treated with 100 μg of cycloheximide/ml to freeze the translating ribosomes on the RNA. The cells were then lysed, and the lysate was layered onto sucrose gradients to resolve the various ribosomal particles. In the uninduced cells, a small but definite 40S peak and a distinct 60S peak were observed (Fig. 2A). The polysomes were well defined with increasing numbers of ribosomes. In contrast, the cells induced for NOPP44/46 RNAi had a prominent 40S peak and no visible 60S peak. In addition, the polysome peaks were detected as doublets or half-mers (Fig. 2A). Half-mers result from 40S subunits stalled at the start codon, waiting for recruitment of a 60S subunit. They have been seen in cells that have a 60S biogenesis defect, including yeast (for examples, see references 24 and 30 for yeast and 13 for T. brucei). These data indicate a requirement for NOPP44/46 in 60S biogenesis.

FIG. 2.

NOPP44/46 is required for large-ribosomal-subunit biogenesis. (A) Polysome analysis of NOPP44/46 RNAi. Lysates from clone A6 cells, either uninduced or induced (day 8), were layered onto 10 to 40% sucrose gradients. The top of the gradient is on the left. The peaks corresponding to 40S, 60S, and 80S are marked. A horizontal line indicates the location of fractions 8 through 11. (B) Western analysis of NOPP44/46 RNAi polysomes. Fractions 1 to 15 from the induced gradient were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel, and the resulting blots were probed with anti-NOG1. The band representing the full-length protein is marked with an asterisk. The dashed lines connect fractions 8 to 11, which contained the bulk of the full-length NOG1 protein, to the same fractions on the gradient.

The nucleolar GTP-binding protein NOG1 associates with a 60S precursor containing rRNA intermediates, peaking slightly after the mature subunit on sucrose gradients (13). To assess whether NOG1 could still be incorporated in the absence of NOPP44/46, fractions were collected from the induced gradient and analyzed for the presence of NOG1. Even though no visible 60S peak could be seen, the full-length NOG1 protein still localized in fractions slightly after the 60S subunit, indicating that it is still incorporated into the precursor particle (Fig. 2B; see Fig. 4 for comparison with wild-type conditions). The smaller immunoreactive bands seen in the initial fractions are degradation products observed in earlier experiments (13). The proper localization of NOG1 demonstrates that it must interact with the nascent particle before NOPP44/46 function is required. It also indicates that, though not detectable on the gradient by determining absorbance at 254 nm, there are still precursor particles present in the induced cells. This finding is consistent with earlier findings that NOG1 is incorporated into the precursor particle very early in the biogenesis pathway (13, 25).

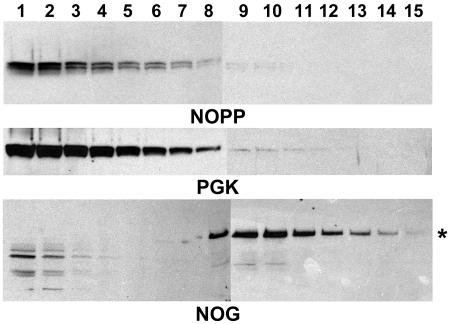

FIG. 4.

NOPP44/46 does not localize with the 60S precursor. Fractions 1 through 15 from the uninduced polysome gradient shown in Fig. 2A were blotted and tested with antibodies directed against NOPP44/46, PGK, and NOG1. For PGK, only the cytosolic isoform is shown. The asterisk in the NOG1 blot denotes the full-length protein.

NOPP44/46 RNAi affects large-subunit rRNA processing.

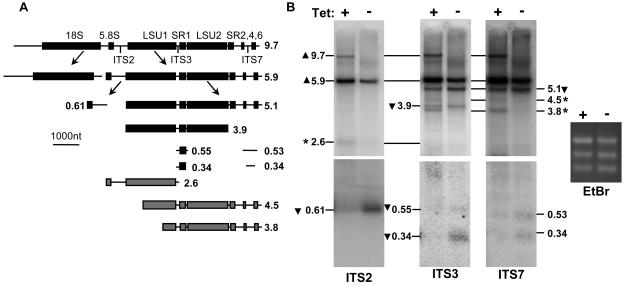

The rRNA precursor is processed via a defined pathway to generate the structural RNAs. In T. brucei, a number of the intermediate products have been identified (Fig. 3A). The large-subunit precursor RNA undergoes processing, with cleavage in ITS2 separating the 5.8S precursor from the remaining genes. The next cleavage within ITS5 separates the two large structural RNAs (LSU1 and LSU2) from the three distal small RNAs (SR2, SR6, and SR4) at the 3′ end. Other known intermediates include precursors to the smaller rRNAs devoid of LSU1 and LSU2 sequences. RNA from induced and uninduced NOPP44/46 RNAi cells was isolated and analyzed to determine which steps in rRNA processing were affected by NOPP44/46 depletion.

FIG. 3.

NOPP44/46 depletion leads to rRNA processing defects. (A) Schematic of T. brucei rRNA processing. The structural RNAs are shown as boxed regions, with the location of the relevant intervening (ITS) region shown below them. The sizes of the intermediates are given in kilobases. The intermediates shown as gray boxes are atypical or aberrant products seen upon NOPP44/46 depletion and marked with an asterisk in panel B. The location of structural RNAs on the 0.55- and 0.34-kb species detected by the ITS7 probe have not been mapped and hence are not shown. (B) Northern analysis of rRNA processing in NOPP44/46 RNAi. Aliquots of the RNA species shown in Fig. 1A for day 7, induced (+) or uninduced (−), were blotted and hybridized with probes for the indicated ITS sequences to examine processing intermediates. Lines connecting the blots align the same precursors. The lower panels for each probe represent results of longer exposures than those for the upper panels, since the smaller fragments were more difficult to detect. The ethidium bromide-stained gel (EtBr) is shown to demonstrate equal loading of the RNA. Precursors whose levels increased (▴) and decreased (▾) are indicated. Bands for aberrant processing intermediates are indicated by asterisks.

Though probes directed against ITS2, ITS3, and IT7 revealed the accumulation of the short-lived full-length rRNA transcript, a 9.7-kb band (Fig. 3B), the significance of this observation is hard to assess, since this transcript was not consistently seen to accumulate and may rather reflect differences in the quality of the RNA preparations. However, there was a consistent increase in the relative abundance of the 5.9-kb precursor compared to that of intermediates later in the pathway, with the concomitant appearance of several atypical species. The 610-bp 5.8S precursor RNA revealed by an ITS2 probe decreased ninefold in the induced sample in comparison to RNA from the uninduced cells. The small precursor bands at 550 and 340 bp detected by the ITS3 probe were essentially absent in the RNA isolated from the induced cells. In contrast, the small precursor bands at 530 and 340 bp that are detected by the ITS7 probe appeared to be less strongly affected, decreasing at most fourfold in the induced samples.

An unusual 2.6-kb product, previously detected by ITS2 probes when NOG1 was depleted, also increased when NOPP44/46 was depleted. The ITS3 and ITS7 probes showed an accumulation of two novel species, represented by a faint 4.5-kb band and a darker 3.8-kb band. No cleavage event within any of the ITS sequences could generate either of these two bands, indicating that at least one of the ends of these molecules must result from an aberrant cleavage within the sequence of the structural RNAs (most likely LSU1). Finally, a probe directed against ITS1, which detects small-subunit precursors, failed to detect any significant differences between the induced and uninduced RNA (data not shown).

NOPP44/46 is not incorporated in the 60S precursor.

Since depletion of NOPP44/46 blocks large-subunit biogenesis, we wanted to determine whether NOPP44/46 associates with the ribosomal precursor particle. The localization of NOPP44/46 in fractions from the uninduced polysome gradient shown in Fig. 2A was examined. The majority of NOPP44/46 protein was found mainly in the initial fractions, one through seven, from the top of the gradient where soluble proteins are found, with protein levels tapering off in additional fractions (Fig. 4). A similar pattern was seen with the soluble protein PGK. In contrast, the NOG1 protein, a component of the precursor (13), had a distinct peak of protein in fractions 8 through 11 (Fig. 2A), corresponding to the 60S (66S) region of the gradient. This finding demonstrates that, though required for 60S biogenesis, NOPP44/46 is not stably incorporated into the nascent particle.

DISCUSSION

Ribosome biogenesis is a highly conserved process, although differences in rRNA processing are evident in many organisms. Some of the most unusual rRNAs occur in protozoa and algae, such as the highly fragmented rRNAs in Plasmodium mitochondria and large-subunit RNAs in Euglena (7, 26). The large subunit rRNA of trypanosomatids (including T. brucei, Leishmania major [16], T. cruzi [4, 11], and Crithidia fasciculata) is fragmented into six molecules corresponding to the 25S rRNA species found in most eukaryotes. This more-complicated processing should require additional novel components. NOPP44/46 is one such component, being both unique to trypanosomatids and required for large-subunit biogenesis. Analysis of genomic sequences from T. cruzi and L. major show the presence of putative orthologues of NOPP44/46, with each of the four domains that characterize the T. brucei protein. No recognizable homolog outside of the trypanosomatids has been found in repeated searches of GenBank. Perhaps most similar are nucleolin and related molecules (e.g., GAR2), which contain acidic regions and RGG repeats. However, the predominant phenotype when these molecules are depleted is an accumulation of the precursors for 40S rRNA and a depletion of the 40S subunit (9, 15). In contrast, the depletion of NOPP44/46 protein through RNAi led to a dramatic decrease in biogenesis of the 60S subunit, with concurrent defects in processing of the large-subunit rRNA. It is interesting that the greatest effects on rRNA processing were observed in the events that surround the cleavages dividing the small RNA SR1 from the two large RNAs LSU1 and LSU2. In cells depleted of NOPP44/46, the smallest SR1 precursors were essentially absent. In addition, we found a number of aberrant processing products that arise from cleavage within the large-subunit RNAs proximal to SR1.

Since NOPP44/46 did not cosediment with the precursor ribosomal particle, what role does NOPP44/46 have in ribosome biogenesis? Though NOPP44/46 lacks any motifs that would suggest a direct role in processing (such as RNase or helicase domains), it does have a series of RGG repeats that allow NOPP44/46 to bind single-stranded DNA and RNA (5). This binding activity could allow NOPP44/46 to recruit processing factors to the site of processing by acting as a bridge between proteins and RNAs. The lack of stable association with the precursor particle does not preclude transient interactions that could be important in such activities.

NOPP44/46 has been shown to interact with a number of the proteins. One interacting protein, NOG1, is a GTP-binding protein that is a component of the 60S precursor. Another set of proteins is p34/p37, a family of nuclear proteins that have been shown to bind 5S RNA (22, 23). NOPP44/46 also associates with protein kinases, one of which is CK2 (18). Still, none of these proteins themselves contain domains or activities consistent with a direct role in RNA processing.

The developmental regulation of NOPP44/46 abundance and phosphorylation suggests the possibility that some aspects of ribosome biogenesis differ between the two life stages of the parasite. Analysis of the recently completed T. brucei genome reveals a family of NOPP44/46-related proteins. Two related genes were found closely linked to the NOPP44/46 gene. These genes (given the systematic names Tb08.12O16.300 and Tb08.12O16.320) both contain a U-like domain, but they lack either the acidic domain or the RGG repeats. An additional U region fragment (Tb08.12016.310) is evident in the present genomic sequence but awaits verification due to ambiguities in assembly. We have shown that at least one of these genes, the most similar to the NOPP44/46 gene (Tb08.12O16.320), is expressed at the RNA level. Given that NOPP44/46 has its strongest effect on the processing involving the small RNA SR1, it is intriguing to speculate that the other NOPP44/46-related proteins could be involved in some of the other unique processing events found in T. brucei.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Englund and Mark Drew for the gift of pZJM, George Cross and Elizabeth Wirtz for the 29-13 cells, Toinette Hartshorne for pGEM-ITS1 and pGEM-ITS2, and Noreen Williams for anti-p34/p37.

This work was supported in part by NIH grant R01 AI31077 and the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust. D.B. received support from NIH grant F32 AI10637.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, S. A., V. Carter, C. B. Hagen, and M. Parsons. 1998. Molecular cloning of the glycosomal malate dehydrogenase of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 96:185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aris, J. P., and G. Blobel. 1988. Identification and characterization of a yeast nucleolar protein that is similar to a rat liver nucleolar protein. J. Cell Biol. 107:17-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brecht, M., and M. Parsons. 1998. Changes in polysome profiles accompany trypanosome development. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 97:189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castro, C., R. Hernandez, and M. Castaneda. 1981. Trypanosoma cruzi ribosomal RNA: internal break in the large-molecular-mass species and number of genes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2:219-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das, A., J.-H. Park, C. B. Hagen, and M. Parsons. 1998. Distinct domains of a nucleolar protein mediate protein kinase binding, interaction with nucleic acids and nucleolar localization. J. Cell Sci. 111:2615-2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das, A., G. C. Peterson, S. B. Kanner, U. Frevert, and M. Parsons. 1996. A major tyrosine-phosphorylated protein of Trypanosoma brucei is a nucleolar RNA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15675-15681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feagin, J. E., E. Werner, M. J. Gardner, D. H. Williamson, and R. J. M. Wilson. 1992. Homologies between the contiguous and fragmented rRNAs of the two Plasmodium falciparum extrachromosomal DNAs are limited to core sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:879-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Girard, J. P., H. Lehtonen, M. Caizergues-Ferrer, F. Amalric, D. Tollervey, and B. Lapeyre. 1992. GAR1 is an essential small nucleolar RNP protein required for pre-rRNA processing in yeast. EMBO J. 11:673-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulli, M. P., J. P. Girard, D. Zabetakis, B. Lapeyre, T. Melese, and M. Caizergues-Ferrer. 1995. gar2 is a nucleolar protein from Schizosaccharomyces pombe required for 18S rRNA and 40S ribosomal subunit accumulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:1912-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartshorne, T., and W. Toyofuku. 1999. Two 5′-ETS regions implicated in interactions with U3 snoRNA are required for small subunit rRNA maturation in Trypanosoma brucei. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3300-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez, R., F. Diaz-de Leon, and M. Castaneda. 1988. Molecular cloning and partial characterization of ribosomal RNA genes from Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 27:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho, J. H., G. Kallstrom, and A. W. Johnson. 2000. Nascent 60S ribosomal subunits enter the free pool bound by Nmd3p. RNA 6:1625-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen, B. C., Q. Wang, C. T. Kifer, and M. Parsons. 2003. The NOG1 GTP-binding protein is required for biogenesis of the 60S ribosomal subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 278:32204-32211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klootwijk, J., and R. J. Planta. 1989. Isolation and characterization of yeast ribosomal RNA precursors and preribosomes. Methods Enzymol. 180:96-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondo, K., and M. Inouye. 1992. Yeast NSR1 protein that has structural similarity to mammalian nucleolin is involved in pre-rRNA processing. J. Biol. Chem. 267:16252-16258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez-Calvillo, S., S. M. Sunkin, S. Yan, M. Fox, K. Stuart, and P. J. Myler. 2001. Genomic organization and functional characterization of the Leishmania major Friedlin ribosomal RNA gene locus. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 116:147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris, J. C., Z. Wang, M. E. Drew, K. S. Paul, and P. T. Englund. 2001. Inhibition of bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei gene expression by RNA interference using the pZJM dual T7 vector. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 117:111-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park, J. H., D. L. Brekken, A. C. Randall, and M. Parsons. 2002. Molecular cloning of Trypanosoma brucei CK2 catalytic subunits: the alpha isoform is nucleolar and phosphorylates the nucleolar protein Nopp44/46. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 119:97-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park, J. H., B. C. Jensen, C. T. Kifer, and M. Parsons. 2001. A novel nucleolar G-protein conserved in eukaryotes. J. Cell Sci. 114:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker, H. L., T. Hill, K. Alexander, N. B. Murphy, W. R. Fish, and M. Parsons. 1995. Three genes and two isozymes: gene conversion and the compartmentalization and expression of the phosphoglycerate kinases of Trypanosoma (Nannomonas) congolense. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 69:269-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons, M., J. A. Ledbetter, G. L. Schieven, A. E. Nel, and S. B. Kanner. 1994. Developmental regulation of pp44/46, tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins associated with tyrosine/serine kinase activity in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 63:69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitula, J., W. T. Ruyechan, and N. Williams. 2002. Two novel RNA binding proteins from Trypanosoma brucei are associated with 5S rRNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290:569-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitula, J. S., J. Park, M. Parsons, W. T. Ruyechan, and N. Williams. 2002. Two families of RNA binding proteins from Trypanosoma brucei associate in a direct protein-protein interaction. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 122:81-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotenberg, M. O., M. Moritz, and J. L. J. Woolford. 1988. Depletion of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ribosomal protein L16 causes a decrease in 60S ribosomal subunits and formation of half-mer polyribosomes. Genes Dev. 2:160-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saveanu, C., D. Bienvenu, A. Namane, P. E. Gleízes, N. Gas, A. Jacquier, and M. Fromont-Racine. 2001. Nog2p, a putative GTPase associated with pre-60S subunits and required for late 60S maturation steps. EMBO J. 20:6475-6484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnare, M. N., and M. W. Gray. 1990. Sixteen discrete RNA components in the cytoplasmic ribosome of Euglena gracilis. J. Mol. Biol. 215:73-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trapman, J., J. Retel, and R. J. Planta. 1975. Ribosomal precursor particles from yeast. Exp. Cell Res. 90:95-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White, T. C., G. Rudenko, and P. Borst. 1986. Three small RNAs within the 10 kb trypanosome rRNA transcription unit are analogous to domain VII of other eukaryotic 28S rRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:9471-9489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wirtz, E., S. Leal, C. Ochatt, and G. A. Cross. 1999. A tightly regulated inducible expression system for conditional gene knock-outs and dominant-negative genetics in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 99:89-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanchin, N. I. T., P. Roberts, A. DeSilva, F. Sherman, and D. S. Goldfarb. 1997. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Nip7p is required for efficient 60S ribosome subunit biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5001-5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, J., and N. Williams. 1997. Purification, cloning, and expression of two closely related Trypanosoma brucei nucleic acid binding proteins. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 87:145-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]