Abstract

Background

The most commonly recommended initial treatment for multidirectional instability is a rehabilitation program. Although there is evidence to support the effect of conservative management on this condition, the published literature provides little information on the exercise parameters of such programs.

Methods

This paper is the second part of a two-part series that outlines a six-stage rehabilitation program for multidirectional instability with a focus on scapula control and exercise drills into functional positions. This paper outlines stages 3 to 6 of this rehabilitation program.

Results and Conclusions

This clinical protocol is currently being tested for efficacy as part of a randomized controlled trial (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry #ACTRN12613001240730). The information in this paper and additional online supplementary files will provide therapists with adequate detail to replicate the rehabilitation program in the clinical setting.

Keywords: exercise, multidirectional instability, scapula, shoulder, rehabilitation

Background

The most commonly recommended initial treatment for multidirectional instability (MDI) of the shoulder is a rehabilitation program.1–3 This paper is the second part of a two-part series that outlines a rehabilitation program for MDI. Part 1 of this two-part series outlined stages 1 to 2 of the Watson MDI Program, which included the assessment of faulty scapula and humeral head (HH) biomechanics, rehabilitation to re-establish scapula control (particularly upward rotation) and control of glenohumeral joint range in lower levels of elevation. The current paper will present stages 3 to 6 with a focus on establishing scapula and HH control and progression of exercises into functional ranges. The successful completion of the initial stages of the rehabilitation program (part 1) is imperative for the MDI patient to ensure adequate scapula and glenohumeral head control to progress through stages 3 to 6.

Preliminary research has shown that this program significantly improves instability specific outcomes, shoulder muscle strength and scapular upward rotation of patients with MDI4,5 and the program is currently being evaluated in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry #ACTRN12613001240730).

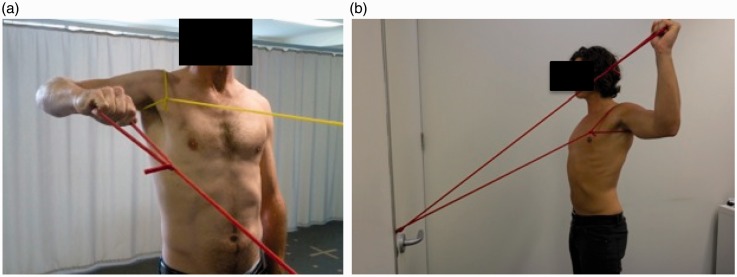

The watson mdi program: intervention

An overview of stages 3 to 6 of the Watson Program is outlined in Table 1 and detailed flow charts of stage 3 to 6 are provided in the Supporting information. Part 1 described the assessment of the patient’s faulty scapula and HH biomechanics to determine what scapula and/or HH position that the patient must retrain and maintain throughout the program. Scapula control is often facilitated with a scapula resistance (SR) band (Figure 1). The SR band is placed around the patient’s scapula and can be used to resist upward rotation, elevation and/or posterior tilt.4,6

Table 1.

Overview of the Watson MDI Program: Stages 3 to 6.

| Stage 3 | |||||

| Scapula phase | Scapula control in sagittal plane | Scapula UR in standing + /– posterior tilt working from coronal plane to sagittal plane | 1 to 3 × 20, 2 × day 0 kgto 0.5 kgto 1 kgto 1.5 kgto 2 kg +/– red–green TB band for tilt | 2 × 20 Scapula UR +/– tilt with 1 kg to 2 kg in sagittal plane 2 × day | |

| Arc of motion phase | Arc of motion control in sagittal plane | Flexion in the scapula plane 0° to 45° elevation Flexion in the sagittal plane 0° to 4° elevation | 1 to 3 × 20 repetitions, 2 × day* Yellow–red–green TB* | 1 or 2 × 20 repetitions flexion drill in the sagittal plane to 45° with load appropriate for function* | Palpate the HH during flexion to assess unwanted HH posterior translation If patient loses scapula or HH control regress to stage 2 for more strengthening |

| Stage 4 | |||||

| Scapula Phase | Scapula control to 90° Abd | Standing Ext row from 45° to 90° Abd | 1 to 3 × 20 repetitions, 2 × day* Red–green TB* | 1 to 3 × 20 repetitions green TB standing Ext row 90° Abd | |

| Arc of motion phase | Arc of motion control to 90° Abd | ER/IR drills: ER at 90° IR at 90° Flexion drills: Flexion to 90° HE to HF drills: Standing Ext row at 90° working around to HF +/– SR band | 1 to 3 × 20 repetitions, 2 × day* Red–green TB* Weights: 0.5 kg to 4 kg* | 1 to 3 × 20 repetitions ER/IR at 90 red/green* 1 to 3 × 20 repetitions flexion to 90 red/green* 1 to 3 × 20 repetitions HF red/green* | ER/IR can be performed between 0° and 90° (e.g. 45° Abd) if functionally required by the patient Abd ER at 90° performed initially in scapula plane if anterior instability |

| Stage 5 | |||||

| Posterior, middle and anterior deltoid muscle strength | Posterior: BOR at 0° to 45° to 90° Abd Anterior: Flexion with TB (stage3), sitting/standing short lever flexion with weight. Middle: Short lever Abd 30° to 90° with weight | 1 to 3 × 8 to 20 repetitions 1 × day to 3 × week* Red–green–blue–black* 0 kg to 0.5 kg to 1 kgto 4 kg* | 1 to 3 × 8 to 20 repetitions, 0 kg to 4 kg* | Bent rows performed to neutral Ext Posterior deltoid drills performed first as easier to control HH, followed by anterior then middle deltoid drills | |

| Stage 6 | |||||

| Arc of motion | Arc of motion control > 90° Abd/elev | ER> 90- EROM* IR > 90-EROM* Flex > 90-EROM* Deltoid drills > 90* | Recruitment/endurance (1 or 2 × 20 repetitions, 2 × day) to strength (3 × 10 to 12 repetitions) to ballistic (1 or 2 × 10 + repetitions) * Yellow–red–green–blue TB* Weight for deltoid: 0 kg to 0.5 kg to 1 kg* | ×20 ER/IR/flex/in range/load to mimic part practice | Integration of trunk stability and overall kinetic chain with shoulder drills needs to be considered |

| Part practice and whole practice | Part practice of function and integration into sport/functional tasks | Part Practice (example): Catch phase of swim over swiss ball Whole Practice: Participation in training/sport/occupation | Part practice dosage and load needs to mimic demands of task Whole practice progressed from small volume to larger volume | Return to sport/occupation/function |

Repetitions of exercises held for 3 seconds to 5 seconds. Abd, abduction; BOR, bent over row; ER, external rotation; EROM, end range of motion; Ext, extension; HE, horizontal extension; HF, horizontal flexion; HH, humeral head; IR, internal rotation; SR, scapula resistance; TB, TheraBand™; UR, upward rotation. *Dosage and load can be progressed from a recruitment and endurance dosage to a dosage and load functionally required by the patient. Exercises may need to be progressed to blue or black bands or heavier weights if functionally required by the patient. For the detailed flow charts for the Watson MDI Program, see the Supporting information.

Figure 1.

Flexion drill with scapula resistance band.

Stage 3: Flexion control from 0° to 45° of elevation

The aim of stage 3 is to achieve control in the sagittal plane (flexion) from 0° to 45° of elevation. Flexion is important to introduce because it is a very functional motion and can usually commence once a standing extension row at 45° (to neutral) has been established against a green TheraBand™ (Hygenic Corporation, Akron, OH, USA) for 20 repetitions. Flexion has a high activation of serratus anterior and thus is essential for improving serratus anterior strength and therefore upward rotation of the scapula.7 Care must be taken in patients with a component of posterior instability because flexion drills can cause an increased translation of the HH if adequate posterior buttress and control has not been established. Stage 3 is divided into two phases: the scapula phase and the arc of motion phase.

Scapula setting phase

The scapula setting drill that was established in stage 1 (Part 1) is progressed in increments from a standing position in the coronal plane to a standing position in the sagittal plane. The load for this drill may need to recommence with the weight of the arm and be progressed in 0.5-kg increments as control is established.

Arc of motion phase

Flexion drills are performed with a TheraBand™ anchored behind the patient when they perform a forward punching motion (Figure 1). Short arcs of motion are commonly performed with a yellow or red TheraBand™ and progressed to a green TheraBand™ prior to extending the arc. The flexion drills begin at approximately 20° to 30° of shoulder flexion and are progressed to 45°. Patients with a large component of posterior instability may have to commence flexion drills in the scapula plane and progress in increments around to the sagittal plane.

Stage 4: Sagittal plane and coronal plane control from 45° to 90° of elevation

The aim of stage 4 is to progress movement control to 90° of elevation in the coronal and sagittal plane. Stage 4 is divided into two phases: the scapula phase and the arc of motion phase.

Scapula phase

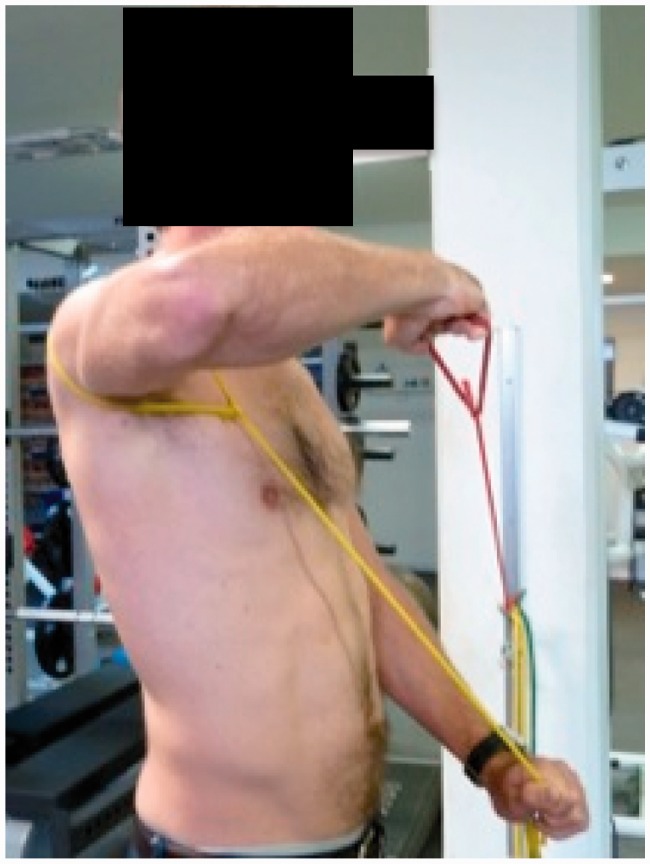

The scapula phase involves gaining control of the scapula in an extension row motion from 45° to 90° of abduction, from a red to green TheraBand™ and even heavier bands (blue/black) if functionally required for the patient (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a) Extension row at 90° of abduction. (b) External rotation at 90° of abduction.

Arc of motion phase

The arc of motion phase is subdivided into 3 parts: internal rotation (IR) and external rotation (ER) at 90° of elevation, flexion at 90° of elevation, and horizontal extension into horizontal flexion.

IR and ER at 90

The extension row drill at 90° of abduction prepares the patients for ER at 90° (Figure 2b). Patients with significant anterior instability may need to initially reduce their arc of ER or bring the drill forward into the plane of the scapula, working around into the coronal plane once control of the HH is sufficient. IR at 90° is usually commenced once the patients can perform 20 repetitions of ER at 90° with a red TheraBand™.

Flexion at 90°

Flexion drills are performed to 90° of elevation. Load is determined by the functional and sporting requirements of the patient.

Horizontal extension into horizontal flexion

Horizontal flexion causes a large degree of posterior HH translation and needs to be controlled for activities such as taking off a tight top, driving a car, and sporting actions such as a backhand in tennis. The horizontal extension into horizontal flexion drill is a progression from the standing extension row at 90° elevation. The drill requires the patient to perform a horizontal extension movement from a starting position of relative horizontal flexion. Over a number of weeks, the drill is progressed into a starting position of more horizontal flexion by the patient gradually turning their body in increments towards their affected shoulder until they are in a starting position with their arm across their chest (Figure 3). TheraBand™ resistance is slowly increased at each angle of horizontal flexion until a load is achieved that is comparable with the patient’s functional requirements.

Figure 3.

Horizontal flexion drill.

Stage 5: Isolated deltoid drills

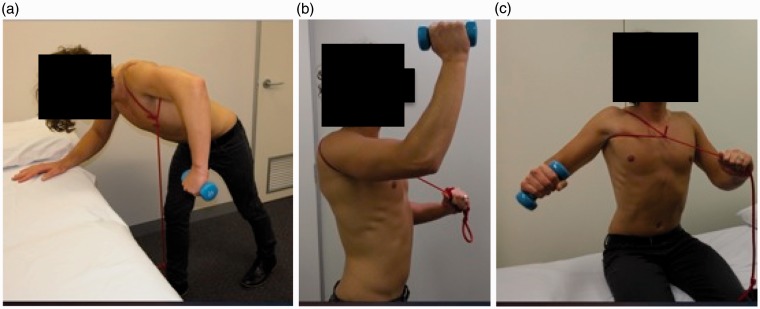

The aim of stage 5 is to develop specific strength in the anterior, middle and posterior deltoid at the same time as maintaining scapula and HH control. Deltoid muscle strength contributes to centering of the HH, as well as normal shoulder kinematics.8 Guidelines for stage 5 are outlined in Table 1; however, drills may commence in conjunction with earlier stages of the program for some patients.

Bent over rowing drills for posterior deltoid (stage 2) are progressed in load at 0° abduction. Simultaneously, bent over rowing drills are progressed in increments to a bent over row at 90° abduction (Figure 4a). Anterior deltoid drills are performed as a flexion action9 in supine, sitting or standing depending on the patient (Figure 4b). Care must be taken prescribing supine drills because they can cause posterior HH translation if they are not well controlled. A rolled up towel behind the humerus can provide additional posterior support. Middle deltoid drills are performed initially in small ranges of abduction with a short lever (Figure 4c), working to ranges that are required by the patient.

Figure 4.

(a) Bent over row at 90° abduction for posterior deltoid. (b) Flexion for anterior deltoid. (c) Short lever abduction for middle deltoid.

Stage 6: Sports-specific and functional specific stage

The aim of stage 6 is to progress arcs of motion beyond 90° and then into task specific, occupational specific and sports-specific drills. Stage 6 is divided into the arc of motion phase and then the sports-specific/functional specific phase.

Arc of motion phase

Prior to commencing exercises that mimic the details of a specific movement (i.e. tennis serve), patients may need further steps of progression. This often involves IR, ER, deltoid and flexion drill from 120° and up to end of range of abduction with the TheraBand™ in varying positions, emphasizing end of range upward rotation control. Integration of the kinetic chain must also be considered in this phase if not prior.10

Sports-specific and functional specific ranges

Part practice

This stage requires the exercises to be functional and should closely mimic the sport/activity. Breaking down drills into subcomponents can be useful for the patient to gain control over the entire motion (Figure 5). Dosage at this phase needs to represent what is functionally required of the patient. Consider the differences between part practice drills for someone needing control at a computer (low load, high repetitions), compared to a person who needs to lift the occasional heavy weight overhead for work (high load, lower repetitions). Depending on the sporting and occupational demands of the patient, the program can emphasize concentric and/or eccentric or ballistic (plyometric) actions. Weight-bearing exercises (progressing from wall weight bearing drills to full weight bearing drills) can be utilized if the patient functionally requires them. Weight bearing drills should not be prescribed when any component of posterior instability remains.

Figure 5.

Part practice of the pull phase of a freestyle stroke in swimming. Part practice of the catch phase and recovery phase would also be implemented.

Whole practice

Once the patient has gained control of part practice drills, then whole practice execution of the drills can be emphasized, with gradual return to training and work, and with gradual increases in volume, as the therapist considers appropriate.

Maintenance programme

Once a patient has reached their goals and completed the program, they are encouraged to continue a maintenance program at two or three times a week of four to eight exercises to maintain their level of function. This often involves the patient performing their weights exercises on one day and band exercise on another day. It is important that the patient understands any limitations that they may have as a result of their condition. For example, some more severe cases of MDI require strict activity limitations and should be advised not to return to certain activities (e.g. contact sports) or should be advised to limit activities (e.g. some gym exercises, amount weight used and/or higher volumes of specific activities).

Parameters

Dosage

Dosage is based on the number or repetitions that the participant can achieve pain free and with good scapula control. Exercises typically commence with a recruitment dosage (1 to 3 sets of 20 repetitions performed 2 or 3 times a day), followed by an endurance dosage (1 to 3 × 10 to 15 repetitions 1 or 2 times a day), and moving onto a strength dosage in later stages (3 to 4 sets of 8 to 12 repetitions performed every second day).11 For most exercises, repetitions are held for 3 seconds.

Load

Load with weights typically commences with 0 kg (the weight of the arm) and progresses in 0.5 kg increments to a minimum of 2 kg for most exercises. TheraBand™ exercises typically commence with yellow and progress to a minimum of red for females and green for males. The progression of load depends on the functional and sporting requirements of the patient. Most patients will need to be progressed beyond to 2 kg and some patients beyond the green TB (for load guidelines, see Table 1).

Progression of exercises

Progression of exercise drills through the program can be achieved by increasing the arc of motion, increasing the load, changing the dosage or increasing the level of elevation in which the patient performs the drill. Table 1 and the flow charts (see the Supporting information) and previous series guide the therapist through a typical format of progressions for the MDI patient. Clinical signs that indicate a patient is ready to progress include: patients are able to perform their previously prescribed exercises with no symptoms; the physiotherapist observes the patient perform their current exercises with good scapula and HH control; and the patient can maintain good scapula and HH control when the physiotherapist isometrically loads them in the position that simulates the proposed new drill. Exercise drills are continued between stages of the program; however, dosage and load of earlier exercises may be progressed. For example, a patient may be performing stage 4 ER at 90° of elevation with a red band and an endurance dosage but will be continuing ER at 0° with a blue band with a strength dosage.

Pathological limitations

Patients with MDI may have a primary direction of instability.12 This is an important consideration when prescribing exercises. A patient with a predominance of posterior instability will load into flexion at a later stage, whereas a patient with a predominance of anterior instability will need to load into abduction and end range ER at a later stage. Therapist assessment must guide exercise selection.

Patients with MDI often present with comorbidities that may need to be addressed prior to commencing shoulder rehabilitation. These include poor cervical spine posture, poor deep cervical flexor strength, symptomatic thoracic outlet syndrome,13 rotator cuff inflammation, volition instability, and significant levels of pain. The treating physiotherapist needs to be aware of these issues and address them accordingly.

Conclusions

This paper outlines the last four stages of the six-stage Watson MDI program. The Watson MDI Program focuses on developing scapula and HH control prior to exercises into range, and is completed with functional and sports-specific exercises. It provides therapists with a flexible model on which they can deliver treatment, based on assessment and individual patient presentation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: L. Watson has been teaching physiotherapy shoulder courses for over 25 years. This paper outlines a rehabilitation program that is often taught on these courses; therefore publication may strengthen the rehabilitation programme as a course resource. S. Balster, S. Warby, T. Pizzari, and R. Lenssen are casually employed by L.Watson to assist with her shoulder courses. The authors declare that there are no financial interests in any company or institution that might benefit from the publication of the submitted article. There are no competing interests relevant to this publication.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Warby SA, Pizzari T, Ford JJ, Hahne AJ, Watson L. The effect of exercise-based management for multidirectional instability of the glenohumeral joint: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 128–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahu MJ, Trentacosta N, Vorys GC, Covey AS, Ahmad CS. Multidirectional instability: evaluation and treatment options. Clin Sports Med 2008; 27: 671–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerrero P, Busconi B, Deangelis N, Powers G. Congenital instability of the shoulder joint: assessment and treatment options. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009; 39: 124–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson L. Multidirectional instability of the shoulder: what is it? Does physiotherapy work? What should we be doing?, Melbourne: New Moves, Australian Physiotherapy Conference, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson L. Functional and clinical changes in multidirectional instability of the shoulder after conservative rehabilitation. PhD Thesis: La Trobe University, Bundoora, 2015.

- 6.Ganderton C. A novel way to train subscapularis: 17–20 October 2013. Melbourne: New Moves Australian Physiotherapy Association, 2013.

- 7.Decker MJ, Hintermeister RA, Faber KJ, Hawkins RJ. Serratus anterior muscle activity during selected rehabilitation exercises. Am J Sports Med 1999; 27: 784–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wickham J, Pizzari T, Stansfeld K, Burnside A, Watson L. Quantifying ‘normal’ shoulder muscle activity during abduction. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2010; 20: 212–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronberg M, Nemeth G, Brostrom LA. Muscle activity and coordination in the normal shoulder: an electromyographic study. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1990; 257: 76–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saeterbakken AH, van den Tillaar R, Seiler S. Effect of core stability training on throwing velocity in female handball players. J Strength Cond Res 2011; 25: 712–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraemer WJ, Adams K, Cafarelli E, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002; 34: 364–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cordasco FA. Understanding multidirectional instability of the shoulder. J Athlet Train 2000; 35: 278–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson LA, Pizzari T, Balster S. Thoracic outlet syndrome part 1: Clinical manifestations, differentiation and treatment pathways. Manual Ther 2009; 14: 586–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]