Significance

Validation of volatile organic compound (VOC) emission reports, especially from large industrial facilities, is rarely attempted. Given uncertainties in emission reports, their evaluation and validation will build confidence in emission inventories. It is shown that a top-down approach can provide measurement-based emission rates for such emission validation. Comparisons with emission reports from Alberta oil sands surface mining facilities revealed significant differences in VOC emissions between top-down emissions rates and reports. Comparison with VOC species emission reports using currently accepted estimation methods indicates that emissions were underestimated in the reports for most species. This exercise shows that improvements in the accuracy and completeness of emissions estimates from complex facilities would enhance their application to assessing the impacts of such emissions.

Keywords: volatile organic compounds, emissions, emission inventory validation, oil sands, aircraft measurements

Abstract

Large-scale oil production from oil sands deposits in Alberta, Canada has raised concerns about environmental impacts, such as the magnitude of air pollution emissions. This paper reports compound emission rates (E) for 69–89 nonbiogenic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) for each of four surface mining facilities, determined with a top-down approach using aircraft measurements in the summer of 2013. The aggregate emission rate (aE) of the nonbiogenic VOCs ranged from 50 ± 14 to 70 ± 22 t/d depending on the facility. In comparison, equivalent VOC emission rates reported to the Canadian National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) using accepted estimation methods were lower than the aE values by factors of 2.0 ± 0.6, 3.1 ± 1.1, 4.5 ± 1.5, and 4.1 ± 1.6 for the four facilities, indicating underestimation in the reported VOC emissions. For 11 of the combined 93 VOC species reported by all four facilities, the reported emission rate and E were similar; but for the other 82 species, the reported emission rate was lower than E. The median ratio of E to that reported for all species by a facility ranged from 4.5 to 375 depending on the facility. Moreover, between 9 and 53 VOCs, for which there are existing reporting requirements to the NPRI, were not included in the facility emission reports. The comparisons between the emission reports and measurement-based emission rates indicate that improvements to VOC emission estimation methods would enhance the accuracy and completeness of emission estimates and their applicability to environmental impact assessments of oil sands developments.

Accurate reporting of pollution emissions from anthropogenic activities is at the core of environmental management policies. Emission reporting requirements are set through legislation or regulation in many countries; polluters meeting legally set thresholds are required to report emission data to national or jurisdictional emission inventories. Such reports are essential sources of data that are used to create emission inventories for various purposes from tracking pollution release to assessing impacts and hazards, ensuring compliance, taking corrective actions, and forecasting air quality. Emission reports are typically derived from bottom-up approaches, summing up emissions from individual activities either using monitoring data in limited situations or applying emission factors to activities and using material balances and engineering judgements for most pollutants (1, 2). There are uncertainties in emission reports, such as those arising from unaccounted activities, the use of unsuitable emission factors, and unverified engineering judgement. The uncertainties are even higher for fugitive sources, for which no technically sound protocols exist for measuring emissions. Uncertainties and assumptions in reported emission data underline the need for evaluation and validation.

In Canada, large-scale industrial activities, such as the oil sands operations in Alberta, which meet reporting requirements, are legally required to report information on pollution emissions to the National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) using the most appropriate estimation methods (3). The Alberta oil sands are the third largest extractable fossil fuel reserve in the world (4), from which oil production has been steadily increasing to 2.1 million barrels per day in 2013 by both surface mining and in situ facilities (5). The surface mining facilities are large in size, each encompassing an area of 66–275 km2 and consisting of complex activities from ore mining, bitumen and sand separation, and upgrading to tailings management (5). Development on such large scales has increased concerns of its environmental impacts (6–8), including on air quality and human health. Key concerns are the amount and type of pollutants emitted into the environment and the accuracy of the emission reports (8). For example, although SO2 and NOx emission reports for large stacks to the NPRI may be verifiable using continuous emission monitoring systems (CEMS), emission reports for other pollutants and from other sources within oil sands facilities are mostly unverified (8).

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are tightly coupled to atmospheric oxidative capacity, ozone formation, and secondary organic aerosol formation (9–12). A large number of VOCs also have known toxic impacts on human health (13). An accurate VOC emission inventory and its correct breakdown by molecular composition are the basis for assessing impacts, such as those used in numerical models for mapping current exposures and predicting future impacts. In the oil sands region, the presence of VOC pollutants in air is known (14, 15), and their emissions from the oil sands facilities are reported as annual totals to the NPRI together with limited information on chemical composition (3). The emission reports have potentially large uncertainties, because there is no direct VOC emission monitoring (16) due to a lack of suitable monitoring methodologies. Uncertainty is increased further by a lack of applicable emission factors and source-specific chemical profiles, especially for fugitive emissions from the various steps of the production cycle and tailings management.

To date, there have been few direct measurements of emission rates of multiple VOCs from complex industrial facilities because of the fugitive nature of sources, technical difficulties, costs associated with measuring a large number of compounds, and more importantly, a lack of suitable methods to enable emission rate determination. As a result of these challenges, validation of VOC emission reports is only occasionally conducted. The alternative has been evaluations of VOC emissions using emission ratios in ambient air (17–24). In this paper, a unique methodology is shown that provides validation of VOC emission reports using a top-down approach, which allows emission rates for a large number of VOCs and chemical speciation profiles from each oil sands surface mining facility to be determined. The methodology uses a combination of box-like aircraft flight patterns enclosing each of the main surface mining facilities, comprehensive measurement methods at high time resolution, and the development and application of a computational top-down emission rate retrieval algorithm (TERRA) (25) for deriving facility emission rates from measurements of chemical concentration and meteorology. In contrast to previous aircraft VOC emission studies (26–29), horizontal and vertical advection and diffusion, chemical reactions, and air mass density changes, all based on measurements, were included in the computation of mass balance of the VOCs from the aircraft measurements, thus reducing the uncertainties in the derived emission rates (25). Another advantage of this methodology is its ability to provide the emission rates of tracers used for the determination of emission rates for many VOCs from discrete measurements, such as canister sampling. The use of tracers allows for significant expansion of the number of VOCs for emission rate determination. The results of the study represent an independent source of VOC emission data for the oil sands facilities, against which the reported emissions can be evaluated.

Results and Discussion

Emission Rates of VOCs.

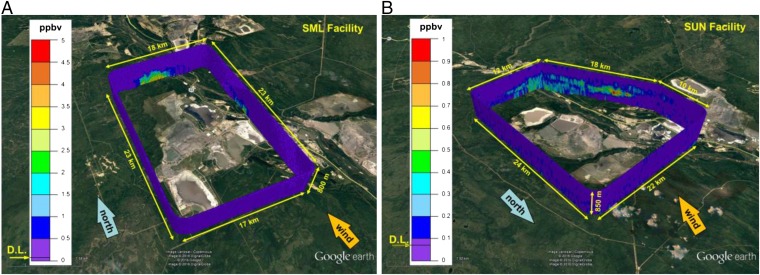

Aircraft flights were made over six major oil sands surface mining facilities in the Athabasca oil sands region, including Syncrude Mildred Lake (SML), Suncor Energy Millenium and Steepbank (SUN), Canadian Natural Resources Limited Horizon (CNRL), Shell Albian and Jackpine (SAJ), Syncrude Aurora (SAU), and Imperial Kearl Lake (IKL) (Methods and SI Appendix, Table S1). Continuous VOC measurements were made using a high-resolution proton transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PTRMS), which detected a series of aromatic hydrocarbons (C6–C12); oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs); a number of alkene-like species, which come from alkenes but can also, in part, arise from interfering cycloalkanes and/or fragments from larger alkanes (30, 31); and biogenic hydrocarbons, all of which had elevated mixing ratios in plumes downwind of the facilities. The results are illustrated in Fig. 1, which shows toluene (C7H8) mixing ratios on the walls of two virtual flight boxes around SML and SUN. Fig. 1 typifies the downwind interception of plumes from a facility by the aircraft tracks and shows the vertical and horizontal distribution of C7H8 in the plumes.

Fig. 1.

(A) Toluene (C7H8) mixing ratios, in parts per billion by volume (ppbv), on the walls of the virtual box created by stacking flight tracks around the SML facility from flight 2. (B) Similar plot for the SUN facility from flight 15. The PTRMS detection limit (D.L.) for toluene is shown on the color scales.

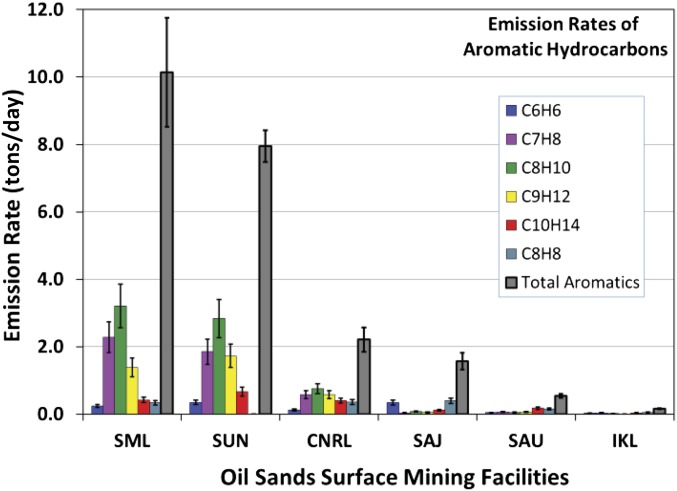

By applying TERRA, emission rates for each of 20 VOCs quantified with the PTRMS for each facility in kilograms per hour were derived over the flight periods. The hourly emission rates were then scaled up to daily compound emission rates (E) based on diurnal changes in the bitumen production and the air temperature during this period (Methods). For example, the E value for C7H8 was derived at 1.6 ± 0.3 and 1.8 ± 0.2 tons/day (t/d) for SML and SUN, respectively, based on the flights shown in Fig. 1. There were variations in E from day to day. The largest variations were seen for C7H8 during the three flights over SML, when E was derived to be 1.6 ± 0.3, 2.3 ± 0.5, and 2.7 ± 0.5 t/d with an average of 2.2 ± 0.7 t/d. For other facilities, the daily variations were smaller (e.g., CNRL E values for C7H8 of 0.61 ± 0.16 and 0.63 ± 0.17 t/d were determined from flights on 2 separate days, averaging to 0.62 ± 0.23 t/d). Among the PTRMS VOCs, the resulting average E from separate flights for aromatic compounds and their sums are shown in Fig. 2. Both the E values for aromatics and OVOCs were included in the aggregate emission rates (aE) of VOCs and are explored further in terms of VOC chemical profiles below. Emission rates E for biogenic hydrocarbons were not included in aE. The alkene E can only be considered as an upper limit to the true alkene emissions because of possible fragmentation in the instrument (Methods) and was not included in aE to avoid double counting of alkenes determined from canisters (below).

Fig. 2.

Emission rates derived from TERRA for the aromatics measured with the PTRMS and their sums.

The E values derived from TERRA represent net transfer rates out of the virtual boxes. However, during the time associated with transport between the emission sources inside a facility and the plume interception by the aircraft, oxidation of the VOCs can occur. Hence, E values derived from TERRA were multiplied by correction factors (A) to account for the oxidative losses of the VOCs during the transport times, which were determined to be between 10 and 60 min based on wind speeds during flights and the main locations of the sources (Methods). Correction factors for E were estimated using known or model-predicted oxidation rate constants (ref. 32; https://www.epa.gov/tsca-screening-tools) (SI Appendix, Table S2), the observed O3 mixing ratios of 30–40 parts per billion (ppb), and a modeled OH radical concentration range of 1–5 × 106 molecules cm−3 (33) during the flights, which is consistent with those typically found in background air (34, 35). The correction factors estimated were between 1.01 ± 0.01 and 1.2 ± 0.2 for each of the aromatics and OVOCs, with the overall uncertainties arising mostly from those associated with the transport times and the OH concentration range (Methods). It is noteworthy that some formation of OVOCs from precursors during the in-box transport was also possible, which would partially offset their oxidative losses. Data from one flight over SML (when the aircraft overflew sources within the facility) indicated that, for acetaldehyde, acrolein, and acetone, the contribution of such formation to E was <30% for each OVOC, whereas it was not possible to determine the formation contribution to the other OVOCs. Such formation contribution, at an upper limit of 30% for all OVOCs, would contribute an upper limit of 4% to the aE at this facility.

Fig. 2 shows that, in all six facilities, aromatics emissions are dominated by the E of C7H8 and C8H10 followed by C9H12. Larger aromatics up to C12H18 were also emitted in significant quantities. The benzene E was relatively small compared with the higher aromatics. All aromatics have high correlations with C7H8 and similar spatial distributions (e.g., Fig. 1), suggesting that they were from the same sources within a facility. Based on results from multiple flights over the facilities, the total aromatic emission rates are 9.7 ± 1.5, 7.9 ± 0.5, 2.1 ± 0.3, 1.5 ± 0.2, 0.53 ± 0.06, and 0.15 ± 0.02 t/d at SML, SUN, CNRL, SAJ, SAU, and IKL, respectively, made up of similar proportions of aromatics at SML, SUN, and CNRL but different proportions at SAJ, SAU, and IKL. The higher aromatic emission rates coupled with the similarities in the aromatic compositions at SML, SUN, and CNRL likely reflect the use of naphtha as solvents in the bitumen extraction process at these facilities. At SAJ, SAU, and IKL, paraffinic solvents are used (36), consistent with the lower aromatic emission rates at these facilities.

The PTRMS cannot quantitatively measure alkanes in complex mixtures; hence, specific E values derived from PTRMS measurements represent only a fraction of overall VOC emissions. To expand the number of VOC compounds measured, discrete canister samples were collected in and out of oil sands facility plumes on flights around four facilities (SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ) followed by laboratory analyses (37) (Methods) for 154 C2–C10 alkanes, alkenes, aromatics, and halogenated hydrocarbons. This VOC list contains some PTRMS VOCs, for which there was excellent agreement with canister-based measurements (Methods). Due to the discrete nature of canister sampling, the canister measurements could not be used directly in TERRA to determine E. Instead, PTRMS VOCs (e.g., C7H8) were used as tracers for the majority of the canister VOCs; for several canister VOCs, the concurrently measured CO and CH4 (Methods) were better tracers and hence used. Therefore, E values for the canister species were derived by multiplying the E of the tracer determined using TERRA (e.g., Fig. 2) by the emission ratios of canister VOCs to the tracers (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) as derived below.

To determine the emission ratios of canister VOCs to the tracers, the mixing ratio correlations with all potential PTRMS tracers were first investigated for each canister VOC and each facility (Methods). The tracer with the highest correlation coefficient (R2) was chosen for the canister VOC (SI Appendix, Tables S8–S11). For example, for SML, PTRMS C7H8 was found to have the highest R2 values for 35 canister VOCs and used as the tracer for these VOCs, whereas PTRMS C9H12 had the highest R2 with 6 canister compounds and was used as the tracer for these 6 VOCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Overall, 10 PTRMS tracers were used for 82 canister VOCs at SML based on correlation coefficients R2 > 0.80. Likewise, 10 tracers had an R2 > 0.88 for 74 canister VOCs at SUN, 15 tracers had an R2 > 0.87 for 70 canister VOCs at CNRL, and 9 tracers had an R2 > 0.88 for 89 canister VOCs at SAJ. Other canister VOCs did not show significant correlations with any tracer, and their emission rates were not quantified. From these correlations, a regression slope was obtained for each pair of canister VOC and tracer. Next, for all canister VOCs, the correction factors for oxidation losses during transport from sources to aircraft plume interceptions were estimated similarly as for the tracers (SI Appendix, Table S2). The correction factors were between 1.000 ± 0.003 and 1.3 ± 0.2 for alkanes and aromatics in the canisters. They were larger at between 1.07 ± 0.03 and 5.0 ± 4.8 for the individual nonbiogenic olefins because of their fast reactions with O3, but the total nonbiogenic olefin contributions to the overall VOC emissions were minor (SI Appendix, Table S3); the nonbiogenic olefin corrections changed the overall VOC emissions by <0.5%. For each pair of canister VOC and tracer, the correction factors for both were applied to the regression slope to derive the emission ratio at the source (Methods). The emission ratio was then multiplied by the tracer E to determine the E for the canister VOC for four facilities (SI Appendix, Table S3).

Total VOC Emissions.

The combined numbers of VOCs from both the canisters and the PTRMS with quantifiable E values for SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ were 89, 77, 73, and 93, respectively, mainly made up of alkanes, aromatics, some alkenes, and biogenics from the canisters and OVOCs from the PTRMS. Excluding the biogenic species, the numbers of VOC species were 88, 73, 69, and 89 for SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ, respectively (SI Appendix, Table S3). Adding the E values of these nonbiogenic VOCs yielded aE values of 50 ± 14, 50 ± 12, 70 ± 22, and 46 ± 15 t/d for the SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ facilities, respectively. The overall uncertainties were due to those in the measurements, the TERRA method, the correction for oxidative loss, the hourly to daily conversion, the daily changes over the study period, and the emission ratios (Methods). The aE would be higher if more compounds were included. For example, isoprene and terpene E values (SI Appendix, Table S3) were not included in aE because of the likely contributions from biogenic sources; however, they are known to be emitted from bitumen production, freshly exposed bitumen ore, and tailings ponds (38). Higher molecular weight compounds beyond those of 73–93 measured VOCs are also known to be emitted, mostly from mine faces and tailings ponds. For example, analytically unresolved hydrocarbons (URHCs), ranging from C10 to C16 and higher, are known to be present in oil sands air emissions (33, 39). These compounds are intermediate and semivolatility organic compounds, with air saturation vapor concentrations in the range of 104–107 μg/m3. They were proposed as the precursors of secondary organic aerosols measured downwind from the facilities (33). These hydrocarbons cannot be quantified using either of the detection methods used in this study, thus their emission rates were not determined.

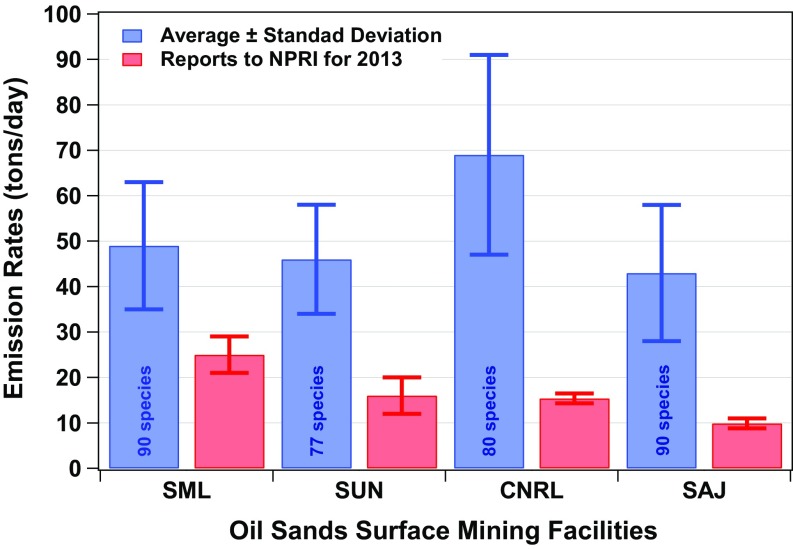

To compare the aE results with facility VOC emission reports to the NPRI, mining truck VOC emissions (Emt) must first be subtracted from aE, because they are not required in the reports to the NPRI (3). Mining truck VOC emissions are reported, however, to Alberta Environment and Parks, and Emt for 2013 may be estimated using the daily mining truck VOC emissions estimated for 2010 (38) but scaled to the 2013 volumes of mined oil sands (40) with estimated uncertainties (SI Appendix, section S5). Furthermore, because the virtual boxes over SML and SUN included 17 and 13 km of Highway 63, respectively, VOC emissions from its on-road traffic on these road sections were estimated (SI Appendix, section S6) and included in Emt for subtraction from aE at both facilities. Emt was thus estimated to be 1.0 ± 0.1, 3.6 ± 0.6, 0.4 ± 0.1, and 3.2 ± 0.4 t/d (1–7% of aE) at SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ, respectively. Subtracting Emt from aE [i.e., (aE − Emt)] resulted in VOC emission rates of 49 ± 14, 46 ± 12, 69 ± 22, and 43 ± 15 t/d from nonmobile sources in four facilities, respectively, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Measurement-based aE of VOCs for four surface mining facilities in the oil sands region after subtracting the mining fleet emissions (blue; in the text). Facility VOC emission rates reported to the NPRI for 2013 derived from scaling down to daily emission rates for August and September are shown in red. Note that, for the SML and SUN emission reports to the NPRI, URHCs were subtracted from the total VOC emission reports for the comparison, whereas no subtraction was made for the CNRL and SAJ total VOC emission reports (in the text).

In 2013, annual emissions of total VOCs reported to the NPRI were 20,732, 9,529, 4,328, and 2,614 tons/year (t/y) for total VOCs for SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ (3), respectively, with unspecified uncertainties. SML and SUN included URHCs (C10–C16 hydrocarbons from mine faces and tailings ponds) in their total VOC emission reports to the NPRI, whereas it is unclear whether the CNRL and SAJ emission reports to the NPRI included URHCs. The 2013 URHC annual emission rates were estimated at 13,590 and 4,954 t/y for SML and SUN, respectively, with unspecified uncertainties (39). These URHC emissions were subtracted from the total VOC emissions reported to the NPRI listed above, resulting in emission rates of 7,142 and 4,575 t/y for SML and SUN, respectively, that are appropriate for comparison with the (aE – Emt) results. URHC emission rates of 3,567 and 14,121 t/y were estimated for CNRL and SAJ, respectively, for 2013 (39), close to or in excess of the total VOC emissions reported to the NPRI listed above. Hence, it was assumed that the total VOC emission reports to the NPRI from CNRL and SAJ did not include URHCs, and no subtractions were made.

An appropriate comparison between the (aE – Emt) results and the emission reports would also require that daily emission reports be available over the study period. However, reporting to the NPRI only requires annual totals to be submitted to the NPRI. Thus, for the comparison, the annual total VOC emissions reports, excluding the URHC emissions, were converted to daily emission rates for the measurement period in August and September of 2013 by multiplying the annual rates by K/365, where the K factors were 1.3 ± 0.2, 1.3 ± 0.3, 1.3 ± 0.1, and 1.4 ± 0.2 for SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ, respectively. The K factor was derived by accounting for seasonal variations in VOC emissions from stacks and plants based on the 2013 bitumen production data (40) and tailings ponds and mine faces based on estimates of seasonal emission changes caused by changes in mass transfer via temperature fluctuations (38). Uncertainties in K values reflect the variations in these parameters (Methods). Using these K factors, the NPRI daily emission rates during August and September were estimated from the annual reports to be 25 ± 4, 16 ± 4, 15 ± 1.4, and 10 ± 1.4 t/d for four facilities, respectively (Fig. 3), where the uncertainties were only because of those in the values of K (Methods) and did not represent uncertainties in the emission reports. Compared with the (aE – Emt) results, the NPRI daily emission rates in August and September are lower by factors of 2.0 ± 0.6, 3.1 ± 1.1, 4.5 ± 1.5, and 4.1 ± 1.6 for SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ, respectively. These comparisons indicate that the emissions reports, based on currently accepted estimation methods, underestimated the total VOC emissions.

Chemical Profiles of Emitted VOCs.

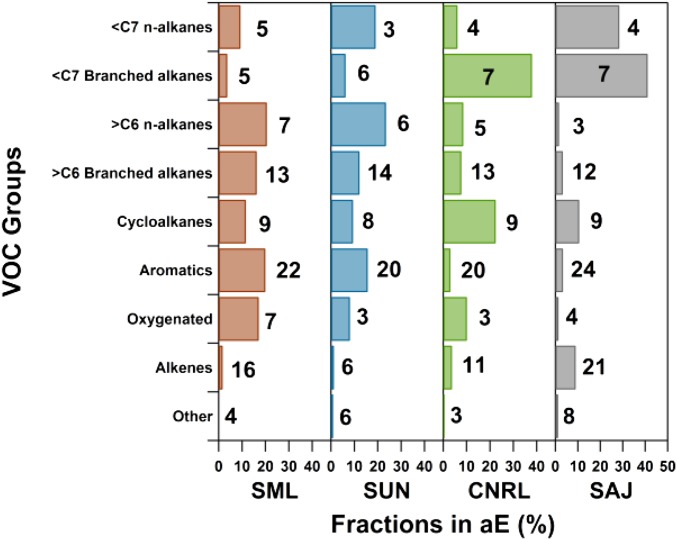

The molecular composition of emitted VOCs from the four facilities can be extracted from the individual E (SI Appendix, Table S3) and used to evaluate the VOC species emission reports to the NPRI. Based on their functional groups and reactivities toward oxidants, the observed VOCs with derived E were separated into nine groups, including ≤C6 and >C6 n-alkanes, ≤C6 and >C6 branched alkanes, cycloalkanes, aromatics, OVOCs, alkenes, and other. The group fractions in aE are shown in Fig. 4 for four facilities. At SML, 39 alkanes accounted for 62.6% of aE, 22 aromatics accounted for 18.7%, and 7 OVOCs accounted for 17.3%. SUN had higher proportions for 37 alkanes (76.6%) and lower proportions for 20 aromatics (15.0%) and 3 OVOCs (7.0%). CNRL and SAJ shared some similarities, with 39 alkanes accounting for 85.4% of aE at CNRL and 35 alkanes contributing 88.0% at SAJ, whereas aromatic fractions were small at 3.1 and 3.7% of aE, respectively. The compound profiles were different among the facilities (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). At SML, the largest contributors were nC8H18, nC7H16, and iC8H18 (7.6, 7.0, and 6.2% of aE, respectively); at SUN, the largest fractions were from nC6H14, nC7H16, and nC5H12 (8.9, 8.6, and 7.0% of aE, respectively). At CNRL, iC5H12 and iC4H10 had the highest fractions of aE (17 and 9.9%, respectively). At SAJ, nC5H12, iC6H14, and iC5H12 were the highest, accounting for 19.9, 12.8, and 11.7% of aE, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Fractions of VOC groups in the aE at four surface mining facilities. Numbers on the bars show the numbers of compounds included in the groups. Aromatics included C6–C10 compounds; oxygenates included CH4O, aldehydes, and ketones; alkenes included straight chain, branched, and cycloalkenes; and others included biogenics.

The main differences in the VOC speciation profiles among the facilities (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) are probably related to differences in plant processes and tailings ponds in the facilities and less attributable to differences in stack, mine face, and mining truck emissions given their reported relative strengths (SI Appendix, Table S12). The large contributions from alkanes, which peak between C4 and C8 (SI Appendix, Table S3), probably reflect the use of solvents in bitumen–sand–water separation in plants and the tailings disposal and storage. SML and SUN are known to use naphtha additives as solvents to expedite the separation, whereas SAJ, SAU, and IKL use paraffinic solvents (36, 38). Both types of solvents contain various portions of paraffinic hydrocarbons with carbon numbers around C6 as the effective ingredients; naphtha solvents have higher carbon alkanes (>C6) and high aromatic content, whereas paraffinic solvents tend to have lower carbon alkanes (≤C6) and much less aromatics (36, 38). The VOC profiles in the measured air emissions reflect such differences: for SML and SUN, the aromatics account for 19 and 15% of aE, respectively, whereas the ≤C6 and >C6 alkanes account for 13.0 and 36.9% at SML and 25.3 and 35.3% of aE at SUN, respectively. At SAJ, the aromatics emissions are only 3.1% of aE (Fig. 4); on the contrary, the ≤C6 and >C6 alkanes account for 69.5 and 4.9% of aE, respectively. The VOC profile at CNRL is less definitive; its aromatic composition is similar to those at SML and SUN (Fig. 2), suggesting use of naphtha as solvents. However, the aromatics accounted for only 3.1% of aE, and the ≤C6 and >C6 alkanes accounted for 44.1 and 16.3%, respectively (Fig. 4), also suggesting the use of paraffinic solvents.

The measurement-based E values for the VOCs for each facility (SI Appendix, Table S3) can serve as validity checks for the annual VOC species emissions reported to the NPRI under the Parts 1 and 5 reporting requirements (41). The NPRI Part 1 requirements are based on human and biota toxicity criteria, whereas Part 5 requirements are for ozone formation potentials (Methods), and some species appear under both requirements. For SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ, the numbers of reported VOC species (including isomers) after combining the NPRI Parts 1 and 5 reports are 29, 32, 18, and 6, respectively, with some species appearing in both Parts 1 and 5 reports. Of the reported species, 26, 23, 13, and 6 species (including isomers) were among 89, 77, 73, and 93 VOC species, respectively, including the biogenic hydrocarbons measured during the study (SI Appendix, Table S3). Hence, only a partial VOC chemical profile comparison can be made.

The comparison shows that there are a number of VOC species with derived E values from the facilities that were not included in the annual species emissions reported to the NPRI, including 22 compounds at SML, 20 at SUN, 42 at CNRL, and 68 at SAJ. Using the daily to annual emission rate conversion procedure (Methods), the daily emission rates of VOCs during the study period, after subtracting mining truck contributions by assuming the same minor fractions of truck total VOC emission Emt in aE, can be scaled up to annual emission rates by multiplying by the scaling factor of 365/K. The correction factor K is the same as used above for downscaling the NPRI annual emission rates (Methods). On this basis, many of the nonreported species will have met the reporting requirements; emissions for additional 14, 9, 24, and 53 VOC species would be reportable under one or both of the NPRI Parts 1 and 5 requirements for SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ, respectively. These VOC species may not have been considered to have met the minimum reporting requirements and thus were not reported.

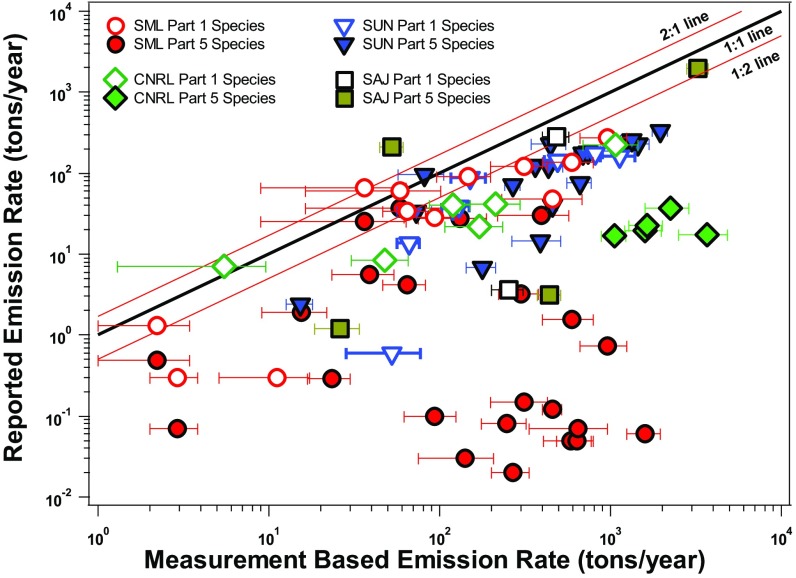

For the species (and isomers) that were reported to the NPRI, their individual E values (SI Appendix, Table S3) were annualized using the scaling factors 365/K and then compared (individually or combined in corresponding isomer groups) with the reported rates, and the ratio of the measurement-based rate to reported rate for each species was calculated (SI Appendix, Tables S5 and S6). Fig. 5 shows the comparison of the annualized measurement-based species emission rates with the facility-reported species emission rates. There are two noteworthy features in Fig. 5. First, there are large differences between the measurement-based rates and the reported rates, with the latter being much lower for the majority of the reported species. Of all 93 VOC species in the annual emission reports from all four facilities combined, 11 could be considered to have observed emission rates similar to reported (with three observed/reported rate ratios from 0.3 to 0.8 and eight ratios from 1.0 to 1.7). On the contrary, 82 species have lower reported emission rates than observed emission rates by a factor of 2–27,800 (SI Appendix, Tables S5 and S6). Given the large spread in the ratios, these differences may be better summarized with nonparametric statistics instead of parametric ones (i.e., means and SDs). For SML, the reported species emission rates are lower than the measurement-based emission rates by a median factor of 2.9 for the 12 Part 1 species, with a lower quartile (LQ) of 1.6 and an upper quartile (UQ) of 5.5, and a much wider margin with a median factor of 375 (LQ of 11 and UQ of 4,550) for 23 Part 5 species. At SUN, eight Part 1 species emission rates are a median factor of 4.0 (LQ of 3.3 and UQ of 5.4) lower than the measured rates; those for 20 Part 5 species are a median factor of 4.5 (LQ of 3.4 and UQ of 6.6) times lower. For CNRL, six Part 1 species emission rates are a median factor of 4.9 (LQ of 3.4 and UQ of 5.6) times lower than the measurement-based rates; those for 10 Part 5 species are a median factor of 60 (LQ of 5.1 and UQ of 72.8) times lower. At SAJ, there are only two species (nC6H14 and C6H6) in the Part 1 report, for which the reported emission rates are factors of 1.7 and 69.9 lower than observations; six Part 5 reported species emission rates are a median factor of 12 (LQ of 1.7 and UQ of 58) lower than observations.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of 2013 emission rates for the individual species reported to the NPRI with the measurement-based emission rates for the same species. Each dot represents a reported species under either Part 1 or 5 reporting requirements (Methods). The horizontal bars represent the uncertainty range of the measurement-based emission rates (Methods).

This comparison clearly shows considerable underestimation in emissions for the majority of the VOC species reported to the NPRI. It is not clear why there was apparent agreement for 11 species and no agreement for the other 82 species. The species in agreement or not have no relation to the magnitudes of emission rates or the chemical functional groups as shown in Fig. 4. However, overall, the reported emission rates for Part 5 species tend to be much lower than measured rates compared with Part 1 reported species. A combination of unrepresentative VOC speciation profiles, emission factors, and/or activity data could lead to such underestimation.

The second notable feature in Fig. 5 is a general lack of linearity between the measurement-based and reported rates for each facility. The lack of linearity indicates that ratios among species in the reports are not the same as the corresponding ratios in the measurement-based emissions (i.e., the species emission reports have speciation profiles different from those in the measured emissions). The differences in the ratios reinforce the likelihood that unrepresentative VOC speciation profiles are an important factor for the differences between the observed and reported species emission rates.

Conclusions

The results demonstrate a methodology through which aircraft measurement-based emission rates for a large number of VOCs for complex industrial facilities can be obtained from a top-down approach. Such emission rate results support the evaluation of legislated or regulatory emission reports that are based on the bottom-up approach. Application of the top-down approach to four large Alberta oil sands surface mining facilities revealed that facility-reported VOC emissions from the four facilities using currently accepted estimation methods are factors of 2.0 ± 0.6, 3.1 ± 1.1, 4.1 ± 1.6, and 4.5 ± 1.5 lower, respectively, than the measurement-based emission rates. The speciated VOC emission reports from all facilities were generally lower than the measurement-based emission rates, by significant factors for most species, indicating the use of inaccurate VOC speciation profiles in the reports. Moreover, based on this work, it was found that 14, 9, 24, and 53 VOC species were reportable under NPRI VOC species reporting requirements but were not included in the species emission reports for four surface mining facilities, respectively. These results showed that evaluation and validation, such as carried out here for VOCs using measurement-based emission rates, are necessary to improve the accuracy and completeness of emission reports. The differences identified from these comparisons point to a need for continued improvement in VOC emission reporting methods to enable a more robust assessment of the environmental impacts resulting from industrial emissions.

Methods

Aircraft Campaign.

Airborne measurements of an extensive set of air pollutants over the Athabasca oil sands region in Alberta were conducted during a 4-week period from August 13 to September 7, 2013 in support of the Joint Oil Sands Monitoring Program (42). Instrumentation was installed aboard the National Research Council of Canada Convair-580 research aircraft. The aircraft flew 22 flights over oil sands surface mining facilities (SI Appendix, Table S1) for a total of 84 flight hours and an average of 4 h per flight. Thirteen flights were designed to quantify facility-integrated air emissions. For these flights, the aircraft was flown in a four- or five-sided polygon pattern encircling a facility, with level flight tracks at 8–10 altitudes increasing from 150 to 1,370 m (500–4,500 ft) above ground and reaching above the mixed layer. These level flight tracks were stacked to form a virtual box surrounding the facility (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The duration of the virtual box flights was from 1.5 to 2 h depending on the facility and the number of level tracks; at least one track was flown above the plume top. The emission flights resulted in 21 virtual boxes around six surface mining operations and 1 in situ operation.

Repeat flights were made over the following facilities: SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ, whereas single flights were made over SAU and IKL (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 and Table S1). For flights over SAU and IKL, continuous measurements using a PTRMS were made but with inadequate canister sampling for emission rate calculation (see below). Hence, emission rates were determined for only a limited number of VOCs, and aggregate VOC emissions rates aE cannot be meaningfully derived for these two facilities. The areas of the virtual boxes encasing six facilities are ∼400, 460, 275, 270, 180, and 110 km2 for SML, SUN, CNRL, SAJ, SAU, and IKL, respectively, with the box walls located at distances of 1–6 km from the facility perimeters. For the average wind speeds experienced during the flights, an air parcel from a facility would travel from 10 to 60 min from the sources within the facility before being intercepted by the aircraft flight tracks and measured by the onboard instruments.

Online VOC and Related Measurements from Aircraft.

Multiple continuous instruments were deployed from the aircraft, measuring various gases and particles, at a time resolution between 1 and 10 s. A PTRMS was used to continuously measure VOCs (30, 31, 43). The VOCs detected on the PTRMS include unsaturated hydrocarbons (e.g., isoprene), aromatics, and a variety of oxygenated compounds, and they were detected using a high-mass resolution time-of-flight mass detector (44). VOC data were collected at a rate of 0.2–1 Hz depending on the flight. The PTRMS drift tube pressure and temperature were maintained constant at 2.15 mbar and 60 °C, respectively. The inlet was rear-facing on the roof of the aircraft. Ambient air was sampled through a 6.35-mm-diameter perfluoroalkoxy sampling line at a flow rate of 6 L min−1 and subsampled by the PTRMS at 270 sccm. The delay time for the instrument was 2 s. Instrumental backgrounds were performed three to four times during each flight for 5 min each using a zero-air unit with a catalytic converter maintained at 350 °C and continuously flushed with ambient air. It removed VOCs from the ambient air while keeping the absolute humidity level of the air unchanged. VOCs were calibrated on the ground with a 1-ppm certified gas standard mixture containing 12 VOCs diluted with zero air (SI Appendix, Table S7). The raw PTRMS data were postprocessed using the TOFWARE software with peak fitting (Tofwerk AG). Of 13 emission flights, 9 flights yielded complete VOC data from the PTRMS. The uncertainty of PTRMS measurements based on analysis of calibration results is 3%.

Among the other continuous measurements from the aircraft, CO and CH4 were measured with a cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS) instrument (Picarro Model G2401) (46). Sampling was through a rear-facing inlet of a 6.35-mm-diameter perfluoroalkoxy line at the roof at a flow rate of 0.436 L min−1. The delay time was 6 s. Instrument background was checked multiple times during each flight. The instrument was calibrated with standards that are traceable to the Global Atmospheric Watch Central Calibration Laboratories standards maintained at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Earth Systems Research Laboratory Global Monitoring Division (45). TERRA was applied to each of these compounds to determine their emission rates (46), and the emission rates were used in combination with emission ratios (below) to determine the emission rates of several VOC species from the canisters (SI Appendix, Tables S8–S11).

Canister Sampling and Laboratory Analyses.

A total of 682 3-L stainless steel canister samples and procedural blanks were collected during the airborne program and then analyzed for 154 VOCs, including C2–C12 n-alkanes, branched alkanes, cycloalkanes, alkenes, aromatics, and halogenated hydrocarbons, postflight in the National Air Pollution Survey (NAPS) analytical laboratory as per the NAPS analysis protocols (37). Reported uncertainties from this method are 30% for concentrations below 0.02 μg m−3, 20% for 0.02–0.2 μg m−3, and 10% above 0.2 μg m−3 (37), which were converted to mixing ratios in SI Appendix, Table S8. Before each flight, precleaned and passivated canisters under vacuum were connected to sampling manifolds, each containing six canisters. The manifold sampling line consisted of stainless steel lines and shutoff valves, which were preflushed with ultrahigh-purity nitrogen and pressurized at 20 psi to prevent contamination from leakage. For each flight, multiple manifolds with clean canisters were loaded on board, and one manifold with six canisters was connected to a 6.35-mm-diameter stainless steel sampling line and a stainless metal bellow compression pump. Manifolds were manually switched for sampling in flight. The canister sampling was performed manually by flushing the manifold sampling line with outside air before pumping air into each canister. The sampling period of each canister was 20 s, pressurizing the canister to 30 psi. For each flight, 20–65 canister samples were collected mostly during plume encounters, with about 20% collected upwind of the facilities. Overall, the numbers of canister samples collected were 109, 138, 104, and 89 over the SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ facilities, respectively.

PTRMS–Canister Comparison.

A comparison between the canister and PTRMS data shows good agreement between the two methods for toluene and C2-benzenes (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). For toluene, the coefficient of determination r2 = 0.87, and the slope of the regression was 0.91 (n = 236). For the C2-benzenes, r2 = 0.93, and the slope of the regression was 1.18 (n = 187). Higher values were reported in the sum of the C2-benzenes from the canisters. The PTRMS was calibrated using o-xylene only; ethylbenzene may have fragmentation in the PTRMS, resulting in an underestimation for the C2-benzenes by the PTRMS.

Comparison of benzene results shows overestimation in the PTRMS benzene results at SML, SUN, and CNRL, where aromatics-rich naphtha is used as the solvent to extract bitumen from the oil sands (36). This difference is most likely caused by larger aromatics, such as ethylbenzene, butylbenzene, and propylbenzene, from fugitive emissions of naphtha use at these facilities. These large aromatics produce a fragment at m/z 79 in the PTRMS, thus interfering with the benzene measurement (30, 31). There was minimal PTRMS benzene overestimation at SAJ or SAU, where paraffinic solvents are used. Some studies have shown good agreement for benzene when comparing with other sampling techniques (17, 43), whereas others have shown that benzene by the PTRMS is overestimated by 16% (46, 47). A correction factor for benzene was calculated by comparing the PTRMS signal at mz79 with the in-plume canister data for benzene from each facility. The results for the C6H6 from the canisters were used for the final emission rate calculation for C6H6.

TERRA.

The TERRA routine (25) was developed to determine facility-integrated emission rates from aircraft measurements over industrial facilities, such as the oil sands surface mining operations. It resolves the air mass balance within a virtual box and determines the mass fluxes across the walls to derive an emission rate for a pollutant based on the divergence theorem. The emission rate is determined using the equation

| [1] |

where the individual terms, in sequence, represent fluxes caused by horizontal advection into and out of the box (EH), horizontal turbulence (EHT), vertical advection (EV), vertical turbulence (EVT), dry deposition (EVD), air mass density change over the flight duration (EM), and chemical changes in the compound within the box volume (Ex). Following the uncertainty analysis in ref. 25, the turbulence (EHT and EVT) and dry deposition (EVD) terms were considered negligible. All other equation terms are evaluated using airborne measurements of the mixing ratio of the compound, air temperature, pressure, and wind speed and direction (25). The chemical change (EX) is discussed separately in the next section.

To apply TERRA, the measurements need to be continuous and of high time resolution (≤10 s). The continuous PTRMS VOC data thus were suitable for application with TERRA to determine the emission rates of the VOCs for each of the facilities. The VOC mixing ratios and meteorological data along the flight tracks were interpolated to a fine mesh on the virtual walls using a simple kriging method and further extrapolated from the lowest aircraft altitude (150 m) to the ground by assuming a well-mixed layer below this altitude. This downward extrapolation often led to the largest source of uncertainties in the derived emission rate, whereas uncertainties from equation terms are small, resulting in an overall uncertainty δT ≤ 30% (25). Depending on wind direction, emissions from upwind facilities were shown to have an impact on the calculation of contaminant entering some of the flight virtual boxes. In most cases, this impact was eliminated through mass balance calculations. During three of the box flights, however, mass–balance tests showed that emissions from upwind facilities passed through the corners of the virtual boxes (where wind measurements had large uncertainties), resulting in total emission rate uncertainties of >50%. Hence, these boxes were excluded from additional calculations, and only TERRA results from nine successful box flights are presented in this paper.

Correction for Oxidation Loss.

The emission rates derived from TERRA represents net transfer rates out of the virtual box. However, the time lags caused by transport between the sources within a facility and the plume interception locations during each flight will result in oxidation of the VOCs to various degrees, and hence, the term Ex in Eq. 1 is not zero. Ex can be evaluated considering that chemical changes for the VOCs are through the oxidation of a VOCi through its reactions with the OH radical and O3 as given by

where ki,OH and ki,O3 are reaction rate constants for the reactions of the compound VOCi with OH and O3, respectively. The rate constants are measured (32) or based on model prediction (https://www.epa.gov/tsca-screening-tools).

To correct for the oxidative decay in VOCi during the time lag (Δt) from emission sources to downwind aircraft transects of the plume, a correction factor ai can be calculated using the chemical reaction kinetic rate constants to relate the measured concentration to that at the source:

| [2] |

To evaluate the correction factor ai, Δt was determined for each flight based on the average wind speed and direction and the distances from the locations of the sources to the plume interception locations along the aircraft tracks. Hence, multiple lag times Δtm, where m represents five main sources of stacks, plants, mining trucks, mine faces, and tailings ponds, had to be evaluated for the major sources in a facility. Some sources have small footprints, such as plants and stacks, so that more accurate estimates of the lag time Δtm can be obtained. Others are large area sources, such as tailings ponds and mine faces. To estimate the lag time Δtm for an area source, a central location was estimated assuming a uniform source across the source area. The values for Δtm derived in such a way had uncertainties that depended on the wind speed and direction and the location of the sources. The source contribution fractions (fm) for mining trucks, stacks, plants, mine faces, and tailings ponds (38) (SI Appendix, Table S12) were used to weigh the contributions to the derived emission rates, and different lag times Δtm were used to make the corrections to the individual contribution terms as follows:

| [3] |

where [VOCi]t is the concentration observed along the flight tracks, Δtm represents the individual lag times from each major source to the intercepted plume, and Ai represents the weighted oxidation correction factor of the individual ai,m terms. For the observed O3 mixing ratios of 30–40 ppb and an assumed OH radical concentration range of 1–5 × 106 molecules cm−3 (33–35) during the flights and using the observed wind speeds, the correction factor Ai ± ΔAi ranged between 1.01 ± 0.01 and 1.2 ± 0.2 for the aromatic hydrocarbons measured with PTRMS, where the uncertainty ΔAi was determined from the variations in the transport times on different days and the range of chosen OH concentrations. The values of these correction factors are listed in SI Appendix, Table S2 for each of four facilities. To correct for the effect of oxidation, Ai ± ΔAi was applied to the TERRA-determined emission rates to derive the emission rate of VOCi at the source.

Upscaling from Hourly Emission Rate R to Daily Emission Rate E.

The TERRA-derived hourly emission rate R can be converted to a daily emission rate E as follows:

| [4] |

where is the average hourly emission rate, is the TERRA hourly emission rate, and C is a correction factor based on the diurnal changes in production and air temperature during the flight day. This upscaling procedure is consistent with the emission factor-based emission estimation approach and the underlying controlling physical processes. The uncertainties from the procedure were assessed using best available information. C was estimated independently as shown here.

In an oil sands surface mining facility, the hourly emission rate of a VOC, R, is contributed by five main sources (38):

| [5] |

where m represents five main sources of VOCs (mining trucks, stacks, plants, mine faces, and tailings ponds), and is the average hourly emission rate of the VOC from the mth individual contributing source. For mining trucks, stacks, and plants (m = 1–3), because one can assume that their VOC emission rates are derived from corresponding emission factors multiplied by production, Rm can be related to hourly production q at the hour of measurement and the 24-h production p:

| [6] |

where the implied emission factors were eliminated through the division of the production terms q and p. Similarly, because SO2 emission rates are expected to be proportional to production under normal operating conditions, the production ratio q/p in Eq. 6 can be related to the ratio of hourly to daily SO2 emissions:

| [7] |

where is the hourly emission rate during aircraft measurement, and is the daily SO2 emission rate. Using SO2 as an indicator of plant production is convenient, because hourly and daily SO2 emission rates are available from CEMS measurements. The underlying assumption is that plant emissions of all VOCs and SO2 are both related to production, which is consistent with the fundamental assumption for emission factor-based emission reporting.

The diurnal changes in Rm from the mine face and tailings ponds (m = 4, 5) may be assessed by applying a correction factor, bm, to the TERRA-derived hourly emission rate:

| [8] |

To evaluate bm, the daytime air temperature of 22.5 °C and average daily temperature of 15.9 °C are used. A maximum value for bm (1.1 ± 0.2–1.4 ± 0.3 depending on facility) could be calculated if the vapor of each VOC was in equilibrium with its condensed form at sources and obeyed Raoult’s law. Such an assumption would lead to a maximum saturation vapor pressure for the VOC, because the condensed phase is a mixture of hydrocarbons and various solvents. If a more realistic assumption of sublimation from the mine face and Henry’s law partitioning of VOC between gas phase and water for tailings ponds is made and considering the kinetic controls for reaching these equilibria, smaller values need to be used for bm. For the calculations below, the median values for bm of 1.15, 1.10, 1.14, and 1.22 for the SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ facilities, respectively, bounded by 1.0 and the maxima for bm, are used.

Hence, R can be expressed as

| [9] |

where fm are the source contribution fractions as defined above. Thus, the factor C for converting from hourly to daily emission rates can be expressed as

| [10] |

Using the CEMS data for SO2 from the facilities (16), the conversion factors C ± ΔC are derived as 1.04 ± 0.28, 1.04 ± 0.08, 0.98 ± 0.17, and 1.2 ± 0.3 for SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ, respectively. For SAJ, no CEMS data for SO2 are available, and the average of production terms for the SML, SUN, and CNRL facilities is used for SAJ. The uncertainties ΔC are derived from the propagation of the relative uncertainties of each term in Eq. 10 estimated from the CEMS SO2 hourly and daily emission data, the correction factors bm, and the fractions of five sources, including the daily variations in the production. Thus, a factor of 24/C is multiplied by the hourly emission rate R to obtain E.

It should be noted that using SO2 emissions to track production requires additional testing and confirmation; depending on the sources (mining trucks, stacks, and plants), the emission ratios among the VOCs may be different, thus introducing additional uncertainties for Rm vs. for these sources. Refinement of the uncertainties depends on additional studies of VOC profiles from these sources.

When averaged over multiple flights, E has an overall uncertainty ΔE arising from uncertainties in (i) the measurements (δM) given in SI Appendix, Tables S7–S11; (ii) the TERRA application (δT), ∼30% for surface-based emissions (25); (iii) the correction for oxidation loss (δA = ΔA/A) at between 0.5 and 15% depending on species; (iv) the hourly to daily scaling factor (δC = ΔC/C), with values between 8 and 27% depending on facility as shown above; and (v) the daily variability (δD), which depends on facility. Hence, the overall relative uncertainty δE (= ΔE/E) in E can be calculated as

| [11] |

Emission Rate Calculations for VOCs in Canisters.

For VOCs determined in the canister samples, the emission rate of VOCi (Ei) was derived using the emission ratio ER (= Δ[VOCi]0/Δ[VOCj]0) and the emission rate Ej of the tracer VOCj. Ej was determined using TERRA as described above from the continuous tracer VOCj from PTRMS or CO and CH4 measured with a CRDS (SI Appendix, Tables S8–S11). The emission ratio of compounds VOCi to VOCj was calculated as follows:

| [12] |

Here, bi,j is the regression slope of VOCi vs. VOCj and was derived as follows. First, tracer mixing ratios were averaged over the canister sampling times in facility plumes. Second, the tracer correlations with the canister VOCs were investigated to determine which tracer had the highest R2 and hence, the best for each canister VOC. A total of 10 tracers from the PTRMS measurements were used for correlating with 82, 74, 70, and 89 VOCs in canisters from the SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ facilities, respectively (SI Appendix, Tables S8–S11). The tracer with the highest R2 was chosen to derive the regression slope bi,j and its standard error δb of the canister VOC vs. the tracer, such as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S2.

To obtain ER, however, both VOCi and VOCj need to be corrected for oxidation losses during transport from the sources to the aircraft plume interception locations as shown in Eq. 12. The correction factor Ai for each VOCi was calculated as in Eq. 3. For most VOCs, the reaction rate constants were published (32); for the rest, the rate constants were estimated for 8 and 12 VOCs reacting with OH and O3, respectively, with a predictive model (https://www.epa.gov/tsca-screening-tools) (SI Appendix, Table S2). Ai was between 1.000 ± 0.003 and 1.3 ± 0.2 for both alkanes and aromatics in the canisters depending on the compound, facility, and flight but ranged from 1.07 ± 0.02 to 5.0 ± 4.8 for the observed nonbiogenic olefins. It is noteworthy that Ei values derived for the nonbiogenic olefins were minor compared with the other VOC groups (Fig. 4) and that Ai > 2 applied to only a few nonbiogenic olefins (eight, four, two, and five for the SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ facilities, respectively) (SI Appendix, Table S2) and led to <0.5% changes in aE for all facilities.

The emission rate of canister VOCi (Ei) was then calculated as

| [13] |

where Ai and Aj are the oxidation correction factors for VOCi and tracer VOCj, respectively, and Ej is the emission rate for VOCj determined using TERRA.

For Ei derived using Eq. 13, the relative uncertainty δEi (= ΔEi/Ei) was evaluated as

| [14] |

where δEj (= ΔEj/Ej) is the relative uncertainty of Ej and was evaluated using Eq. 11, δbi,j (= Δbi,j/bi,j) is the standard error of the regression slope bi,j, and δA,i and δA,j are the relative uncertainties caused by the oxidation correction of Ai and Aj, respectively.

Scaling Factors to Convert from Daily to Annual Emission Rates and Vice Versa.

The conversion from daily emission rate to annual emission rate (and vice versa) can be similarly treated as the hourly to daily conversion, but the scaling is shown here for the total VOC emissions. Annual total VOC emissions may be expressed as

| [15] |

where is the average daily total VOC emissions over a year, and tE is the daily total VOC emission for a particular period in a year (e.g., August/September). K is a correction factor that relates the average daily emission rate to the daily emission rate during a specific period, such as August to September, accounting for seasonal variation in air temperature and production. As shown below, K can be independently estimated. For a given annual emission report, such as those from the facilities to the NPRI, and using the independently estimated K, tE can be calculated from Eq. 15. Again, such upscaling is equivalent to emission estimation based on emission factors and activity data (in this case, the production-related activities at the facilities plus evaporative processes from surface sources modulated by temperature) as outlined below.

For a given facility, the daily individual contribution terms to tE are as follows:

| [16] |

where tEm is the total VOC emissions from each of four of the five main sources of VOC: stacks, plants, mine faces, and tailings ponds (m = 2–5). Mining truck emissions (m = 1) are not included here, although they are much smaller than the other four sources, because the NPRI emission reports explicitly do not include mining truck emissions.

For m = 2–3 (stacks and plants), the daily emission rates are expected to be proportional to bitumen production:

| [17] |

where p and P are the daily and annual production rates of bitumen, respectively. Production data on a monthly basis are available for each facility (39), from which the annual production and the daily production can be derived, the former by adding up 12 monthly production rates and the latter by dividing the monthly production by the number of days in the particular month.

For mine faces and tailings ponds, the seasonal variations in emissions are related to air temperature and have been modeled based on the seasonal changes in temperature and mass transfer (38). For mine face, the daily emission rate was estimated to be 30% higher than the average daily emissions over a year; for tailings ponds, the daily emission rates in August and September were estimated to be 64% higher than the average daily emissions over a year. Hence, for August and September, the daily emission rates for mining face and tailings ponds can be expressed as

| [18] |

where m = 4 for mine face and m = 5 for tailings ponds. Based on ref. 38, d4 = 1.30 ± 0.29 and d5 = 1.64 ± 0.36 for the emissions from mine face and tailings ponds, respectively. Therefore,

| [19] |

Using Eq. 19, one can derive the factor K from the ratio of the daily emission rate tE to the average daily emission rate :

| [20] |

Using the calculated data for daily bitumen production p in August and September of 2013, annual total bitumen production P for 2013 (37), and the values for d4 and d5 for August and September, as well as the fractions fm for m = 2–5 (SI Appendix, Table S12), the ratios K ± ΔK are calculated to be 1.29 ± 0.17, 1.29 ± 0.16, 1.30 ± 0.12, and 1.42 ± 0.20 for the SML, SUN, CNRL, and SAJ facilities, respectively. ΔK is determined from the variations in monthly production data (39) using a 3-month moving window, the estimated seasonal variations in emissions from both the mine face and tailings ponds (38), and the fractions of four sources. Using these K values, the daily emission rates determined from the measurements during the August and September period can be scaled up to annual emission rates by multiplying by a factor of 365/K. Conversely, annual emission rates may be scaled down by multiplying the annual rates by a factor of K/365 to obtain the daily emission rates during the August and September period. Clearly, the uncertainties ΔK can be further refined with additional emission rate measurements in different seasons.

The NPRI.

The NPRI is Canada’s legislated, publicly accessible inventory of pollutant releases (to air, water, and land), disposals, and transfers for recycling (3). It is mandated under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (1999) and applies to industrial, commercial, and institutional facilities. Reporting is mandatory for facilities that meet various reporting thresholds and rules (e.g., quantities emitted or quantities manufactured, processed, or otherwise used, number of employees, etc.). The NPRI is a key tool for identifying and monitoring emissions from point-type pollution sources in Canada. The NPRI undertakes activities to ensure that the data meet a high standard of quality and also meet the needs of data users (48). The NPRI requirements are designed to capture the most significant point sources, and data on individual substances are required only if the threshold applicable to that particular substance is met or exceeded. Facilities are required to report information that is available to them or to which they could reasonably be expected to have access, but they are not required to do monitoring specifically for the purposes of estimating emissions for the NPRI.

For Part 1A of the NPRI, which listed 230 substances for the 2013 reporting year, a report is required for one or more substances if they were manufactured, processed, or otherwise used at a facility at a concentration ≥1% by weight (except for by-products and mine tailings) and in a quantity of 10 t/y or more and if employees worked 20,000 h or more at a facility during the year (41). In Part 5 of the NPRI VOC speciation reporting, a report is required for any of 75 listed VOCs, which include individual substances, isomer groups, and other groups and mixtures, if they were released to air in a quantity of 1 t/y or greater and if the 10-t/y air release threshold for the facility for total VOCs under Part 4 was met (41). In theory, there can be more than 100 VOC species reported for Part 1 and 75 VOC species or isomer groups for Part 5, with 20 that are also listed in Part 1 (41). In reality, not all species are reported depending on whether reporting requirements are met, and isomers are not separated for many of the reported species. A description of the development of the list of Part 5 species is available (49).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Convair-580 flight crew of the National Research Council of Canada, especially the pilots, for conducting the aircraft flights and making the emission determination possible and the technical and Information Management and Information Technology support staff of the Air Quality Research Division and Mr. Mohammed Wasey for their strong support. Also, we acknowledge the anonymous reviewers for their detailed comments, which helped improve the paper considerably. The CEMS data for SO2 were provided by Data Management and Stewardship, Corporate Services Division, Alberta Environment and Parks. This project was partially funded by Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Climate Change and Air Pollutants Program and the Canada-Alberta Joint Oil Sands Monitoring Program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. F.W. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: The datasets have been published in the Joint Oil Sands Monitoring Plan open data portal, jointoilsandsmonitoring.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=A743E65D-1.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1617862114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.US Environmental Protection Agency . AP-42, Fifth Edition, Compilation of Air Pollutant Emission Factors, Vol. 1: Stationary Point and Area Sources. Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards, US EPA; Research Triangle Park, NC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller CA, et al. Air emission inventories in North America: A critical assessment. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2006;56:1115–1129. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) 2016 National Pollutant Release Inventory. Available at https://www.ec.gc.ca/inrp-npri. Accessed March 16, 2016.

- 4.Government of Alberta 2012 Oil Sand Facts and Statistics. Available at www.energy.alberta.ca/oilsands/791.asp. Accessed March 16, 2016.

- 5.Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers 2016 Technical Report: Statistical Handbook for Canada’s Upstream Petroleum Industry. CAPP Publication #2016-9999. Available at www.capp.ca/publications-and-statistics/publications/275430. Accessed March 16, 2016.

- 6.Kurek J, et al. Legacy of a half century of Athabasca oil sands development recorded by lake ecosystems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:1761–1766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217675110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Small CC, et al. Emissions from oil sands tailings ponds: Review of tailings pond parameters and emission estimates. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2015;127:490–501. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parajulee A, Wania F. Evaluating officially reported polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emissions in the Athabasca oil sands region with a multimedia fate model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:3344–3349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319780111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkowitz CM, et al. Hydrocarbon observations and ozone production rates in Western Houston during the Texas 2000 Air Quality Study. Atmos Environ. 2004;39:3383–3396. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blake DR, Rowland FS. Urban leakage of liquefied petroleum gas and its impact on Mexico city air quality. Science. 1995;269:953–956. doi: 10.1126/science.269.5226.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinman LI, et al. A comparative study of ozone production in five U.S. metropolitan areas. J Geophys Res. 2005;110:D02301. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryerson TB, et al. Effect of petrochemical industrial emissions of reactive alkenes and NOx on tropospheric ozone formation in Houston, Texas. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:4249. [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Environmental Protection Agency 2016 Integrated Risk Information System. Available at https://www.epa.gov/iris. Accessed March 15, 2016. [PubMed]

- 14.Simpson IJ, et al. Characterization of trace gases measured over Alberta oil sands mining operations: 76 Speciated C2-C10 volatile organic compounds (VOCs), CO2, CH4, CO, NO, NO2, O3 and SO2. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:11931–11954. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood Buffalo Environmental Association 2015 Integrated Monitoring Program Annual Report, Volatile Organic Compounds Data Summary 2015. Available at www.wbea.org/resources/reports-and-publications/ambient-air-monitoring-reports/ambient-annual-report. Accessed December 18, 2016.

- 16.Zhang J, et al. 2015 Emissions preparation for high-resolution air quality modelling over the Athabasca oil sands region of Alberta, Canada. Proceedings of the 21st International Emissions Inventory Conference (US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC). Available at www.epa.gov/ttn/chief/conference/ei21/session1/zhang_emissions.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016.

- 17.Karl T, et al. Emissions of volatile organic compounds inferred from airborne flux measurements over a megacity. Atmos Chem Phys. 2009;9:271–285. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petron G, et al. Hydrocarbon emissions characterization in the Colorado Front Range: A pilot study. J Geophys Res. 2012;117:D04304. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilman JB, Lerner BM, Kuster WC, de Gouw JA. Source signature of volatile organic compounds from oil and natural gas operations in northeastern Colorado. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:1297–1305. doi: 10.1021/es304119a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang W, et al. Comparison of organic compound compositions in the emissions inventory and ambient data for the Lower Fraser Valley. J Air Waste Manage Assoc. 1997;47:851–860. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1997.10464457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borbon A, et al. Emission ratios of anthropogenic volatile organic compounds in northern mid-latitude megacities: Observations versus emission inventories in Los Angeles and Paris. J Geophys Res. 2013;118:2041–2057. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldan P, et al. Nonmethane hydrocarbon and oxy hydrocarbon measurements during the 2002 New England Air Quality Study. J Geophys Res. 2004;109:D21309. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilman JB, et al. Measurements of volatile organic compounds during the 2006 TexAQS/GoMACCS campaign: Industrial influences, regional characteristics, and diurnal dependencies of the OH reactivity. J Geophys Res. 2009;114:D00F06. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warneke C, et al. Determination of urban volatile organic compound emission ratios and comparison with an emissions database. J Geophys Res. 2007;112:D10S47. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon M, et al. Determining air pollutant emission rates based on mass balance using airborne measurement data over the Alberta oil sands operations. Atmos Meas Tech. 2015;8:3745–3765. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eerdekens G, et al. Flux estimates of isoprene, methanol and acetone from airborne PTR-MS measurements over the tropical rainforest during the GABRIEL 2005 campaign. Atmos Chem Phys. 2009;9:4207–4227. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karion A, et al. Aircraft-based estimate of total methane emissions from the Barnett Shale region. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:8124–8131. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warneke C, et al. Biogenic emission measurement and inventories determination of biogenic emissions in the eastern United States and Texas and comparison with biogenic emission inventories. J Geophys Res. 2010;115:D00F18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klemm O, Ziomas IC. Urban emissions measured with aircraft. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 1998;48:16–25. doi: 10.1080/10473289.1998.10463672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan B, et al. Interpretation of volatile organic compound measurements by proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry over the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2014;358:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warneke C, De Gouw JA, Kuster WC, Goldan PD, Fall R. Validation of atmospheric VOC measurements by proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry using a gas-chromatographic preseparation method. Environ Sci Technol. 2003;37:2494–2501. doi: 10.1021/es026266i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atkinson R, et al. Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume II – gas phase reactions of organic species. Atmos Chem Phys. 2006;6:3625–4055. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liggio J, et al. Oil sands operations as a large source of secondary organic aerosols. Nature. 2016;534:91–94. doi: 10.1038/nature17646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quay P, et al. Atmospheric 14CO: A tracer of OH concentration and mixing rates. J Geophys Res. 2000;105:15147–15166. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stone D, Whalley LK, Heard DE. Tropospheric OH and HO2 radicals: Field measurements and model comparisons. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:6348–6404. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35140d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao F, Liu Q. Froth treatment in Athabasca oil sands bitumen recovery process: A review. Energy Fuels. 2013;27:7199–7207. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Curren KC, et al. Ambient air 1,3-butadiene concentration in Canada (1995-2003): Seasonal, day of week variations, trends, and source influences. Atmos Environ. 2006;40:170–181. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies M, et al. Lower Athabasca Region Source and Emission Inventory. Prepared for the Cumulative Environmental Management Association (CEMA) 2012 Available at library.cemaonline.ca/ckan/dataset/0cfaa447-410a-4339-b51f-e64871390efe/resource/fba8a3b0-72df-45ed-bf12-8ca254fdd5b1/download/larsourceandemissionsinventory.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alberta Environment and Parks . Air Pollutant and GHG Emissions from Mine Faces and Tailings Ponds. in press Alberta Environment and Parks; Edmonton, AB, Canada: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alberta Energy Regulator 2013 ST39: Alberta Minable Oil Sands Plant Statistics. Report St39-2013. Available at www.aer.ca/data-and-publications/statistical-reports/st39. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- 41.Canada Gazette 2012 Version of NPRI Reporting Requirements in Force for 2013 Reporting Year. Available at www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2012/2012-12-29/pdf/g1-14652.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016.

- 42.Joint Oil Sands Monitoring Plan 2012 Canada-Alberta Oil Sands Environmental Monitoring Information Portal. Available at www.jointoilsandsmonitoring.ca/default.asp?lang=En&n=5F73C7C9-1. Accessed January 15, 2016.

- 43.De Gouw JA, et al. Validation of proton transfer reaction-mass spectrometry (PTR-MS) measurements of gas-phase organic compounds in the atmosphere during the New England Air Quality Study (NEAQS) in 2002. J Geophys Res. 2003;108:4682. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graus M, Müller M, Hansel A. High resolution PTR-TOF: Quantification and formula confirmation of VOC in real time. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tuomas T, editor. 2009 GAW Report No. 186: 14th WMO/IAEA Meeting of Experts on Carbon Dioxide, Other Greenhouse Gases and Related Tracers Measurement Techniques (World Meteorological Organization, Geneva). Available at library.wmo.int/pmb_ged/wmo-td_1487.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2016.

- 46.Jobson BT, et al. On-line analysis of organic compounds in diesel exhaust using a proton transfer reaction mass spectrometer (PTR-MS) Int J Mass Spectrom. 2005;245:78–89. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jobson BT, et al. Comparison of aromatic hydrocarbon measurements made by PTR-MS, DOAS and GC-FID during the MCMA 2003 Field Experiment. Atmos Chem Phys. 2010;10:1989–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48.NPRI The NPRI Data Quality Management Framework. Available at www.ec.gc.ca/inrp-npri/default.asp?lang=En&n=23EAF55A-1. Accessed June 15, 2016.

- 49.Moran MD, et al. 2003 An alternate approach to VOC speciation reporting. Proceedings of the 12th Emission Inventory Conference (US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC). Available at https://www3.epa.gov/ttnchie1/conference/ei12/modeling/moran.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2016.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.