Significance

Prostate cancer is an androgen receptor (AR)-dependent disease. Goals in treatment of prostate cancer include keeping low Gleason grades low and preventing development of the lethal disease castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. The present study revealed that ERβ modulates AR signaling by repressing AR driver RORc and increasing AR corepressor DACH1/2. Loss of ERβ resulted in up-regulation of genes whose expression is associated with poor prognosis in prostate cancer accompanied by down-regulation of tumor-suppressive or tumor-preventive genes. Treatment of mice with an ERβ agonist resulted in the nuclear import of PTEN and repression of AR signaling. ERβ may be a promising target for treating early stage prostate cancer to prevent cancer progression.

Keywords: nuclear receptor, cancer prevention, TGFβ, inflammation

Abstract

As estrogen receptor β−/− (ERβ−/−) mice age, the ventral prostate (VP) develops increased numbers of hyperplastic, fibroplastic lesions and inflammatory cells. To identify genes involved in these changes, we used RNA sequencing and immunohistochemistry to compare gene expression profiles in the VP of young (2-mo-old) and aging (18-mo-old) ERβ−/− mice and their WT littermates. We also treated young and old WT mice with an ERβ-selective agonist and evaluated protein expression. The most significant findings were that ERβ down-regulates androgen receptor (AR) signaling and up-regulates the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN). ERβ agonist increased expression of the AR corepressor dachshund family (DACH1/2), T-cadherin, stromal caveolin-1, and nuclear PTEN and decreased expression of RAR-related orphan receptor c, Bcl2, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and IL-6. In the ERβ−/− mouse VP, RNA sequencing revealed that the following genes were up-regulated more than fivefold: Bcl2, clusterin, the cytokines CXCL16 and -17, and a marker of basal/intermediate cells (prostate stem cell antigen) and cytokeratins 4, 5, and 17. The most down-regulated genes were the following: the antioxidant gene glutathione peroxidase 3; protease inhibitors WAP four-disulfide core domain 3 (WFDC3); the tumor-suppressive genes T-cadherin and caveolin-1; the regulator of transforming growth factor β signaling SMAD7; and the PTEN ubiquitin ligase NEDD4. The role of ERβ in opposing AR signaling, proliferation, and inflammation suggests that ERβ-selective agonists may be used to prevent progression of prostate cancer, prevent fibrosis and development of benign prostatic hyperplasia, and treat prostatitis.

Because proliferation in prostate cancer (PCa) is regulated by the androgen receptor (AR), androgen inhibition either by androgen ablation or by blocking of AR signaling remains the key pharmacological intervention in treatment of PCa (1, 2). Although initially effective, this approach eventually leads to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPCa). Clearly, pharmacological intervention that would prevent androgen-mediated proliferation would be of value in the treatment of PCa. Estrogen receptor β (ERβ) is expressed in the prostate, where it is antiproliferative (3, 4). ERβ agonists are promising pharmaceuticals for controlling growth of PCa. Although they have been shown to be antiproliferative in PCa cell lines (5) and mice (6), they have not been tested clinically in PCa. ERβ was cloned from a rat ventral prostate (VP) cDNA library in 1996 (7) and has since been found to be abundantly expressed in the epithelium and stroma of human prostates. Most studies show that ERβ expression is lost in cancers of high Gleason grades (3, 8–10), one study shows that it is more highly expressed in PCa (11), and one shows it is expressed in metastatic prostate cancer (12).

In previous studies, we found no PCa in ERβ−/− mice (the original Oliver Smithies ERβ knockout mouse), but there were regions of epithelial hyperplasia, inflammation, increased expression of Bcl2, and reduced differentiation of the epithelial cells (13). Several ERβ-selective agonists have been synthesized (14–20), and they have been found to be antiinflammatory in the brain and the gastrointestinal tract (21, 22) and antiproliferative in cell lines (23–27) and cancer models (23, 28). We have previously shown that there is an increase in p63-positive cells in ERβ−/− mouse VP but that these cells were not confined to the basal layer but were interdispersed with the basal and luminal layer (13). These data were interpreted to mean a reduced ability of the prostate epithelium to fully differentiate.

In the present study, with RNA-Seq and immunohistochemistry, we examined gene expression in the VP of the ERβ−/− mouse (29), as well as the effect of an ERβ-selective agonist (LY3201) on gene expression in the VP of WT mice.

Results

Histology of the VP in Aging Mice.

As ERβ−/− mice age, there is an increase in the number of hyperplastic and fibroplastic lesions in the VP (Fig. S1). Such lesions can be found in the VP of WT mice over 18 mo of age, which may be a reflection of the loss of ERβ that occurs with age (30).

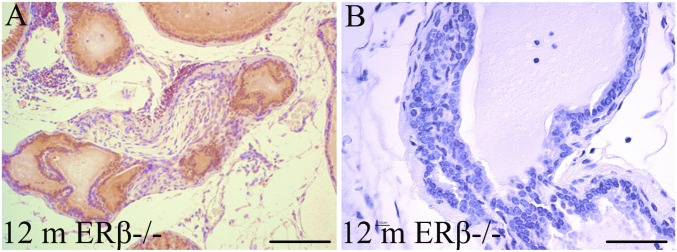

Fig. S1.

Fibroplasia with inflammation (A) and epithelial hyperplasia (B) in the VP of 1-y-old ERβ−/− mice. These types of lesions do occur in the VP of 2-y-old WT mice but are common in ERβ−/− mice. Loss of ERβ with age may be responsible for the lesions in old WT mice. (Scale bars: A, 200 μm; B, 50 μm.)

ERβ-Regulated Genes Identified by RNA Sequencing.

mRNA was extracted from the VP of five WT and five ERβ−/− mice and analyzed by RNA sequencing. From the RNA-Seq data, we chose genes whose expression was changed by fourfold or more.

We found that the most up-regulated genes in the VP of ERβ−/− mice were genes whose expression is associated with poor prognosis in PCa. These were as follows: heat shock protein 60 (HSP60); S100 calcium-binding protein A11 (S100A11); matrix gla protein; tetraspanin-8 (TSPAN8); kallikrein 1 and 8; Src homology 3 (SH3) domain-binding glutamate-rich protein-like (SH3BGRL); the proteases ADAM 15 and 28 and their membrane localization partners TSPAN 4 and 8; the antiapoptotic gene clusterin; the membrane bound androgen receptor SCL39a9; RORc; the cytokines CXCL14, -16, and -17; NFκB and the activator of NFκB, commd; and structural component of E3 ubiquitin ligases CUL1 (Table 1 and Fig. S2).

Table 1.

ERβ-regulated gene expression

| Up-regulated in ERβ−/− mice | Down-regulated in ERβ−/− mice | Regulated by LY3201 |

| RORc | DACH1/2 | RORc (Fig. 3) |

| Clusterin (apolipoprotein J), Bcl2 and -7b | T-cadherin | DACH1 (Fig. 4) |

| Commd RelA/P65 subunit of NFκB | Caveolin1 | T-cadherin (Fig. 6) |

| CXCL14, -16, and -17 | Cystatin c | Smad7 and BCL2 (Fig. 7) |

| TSPAN4 and -8 | Seminal vesicle secreted protein | NFκB (Fig. 8) |

| Kallikrein 1 and 8 | WFDC3 | iNOS, IL6 (Fig. S3) |

| SH3BGRL | Glutathione peroxidase 3 | Caveolin1 (Fig. S4) |

| SCL39a9 | EXPI | PTEN (Fig. 5) |

| HSP60 | ||

| ADAM 15 and 28 | ||

| CUL1 | ||

| S100A11 | ||

| Matrix gla protein | ||

| Spp1 (osteopontin) |

CUL1, cullin 1; DACH1, dachshund family transcription factor 1; EXPI, extracellular proteinase inhibitor; HSP60, heat shock protein 60; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RORc, RAR-related orphan receptor c; SH3BGRL, SH3 domain binding glutamate rich protein like; WFDC3, WAP four-disulfide core domain 3.

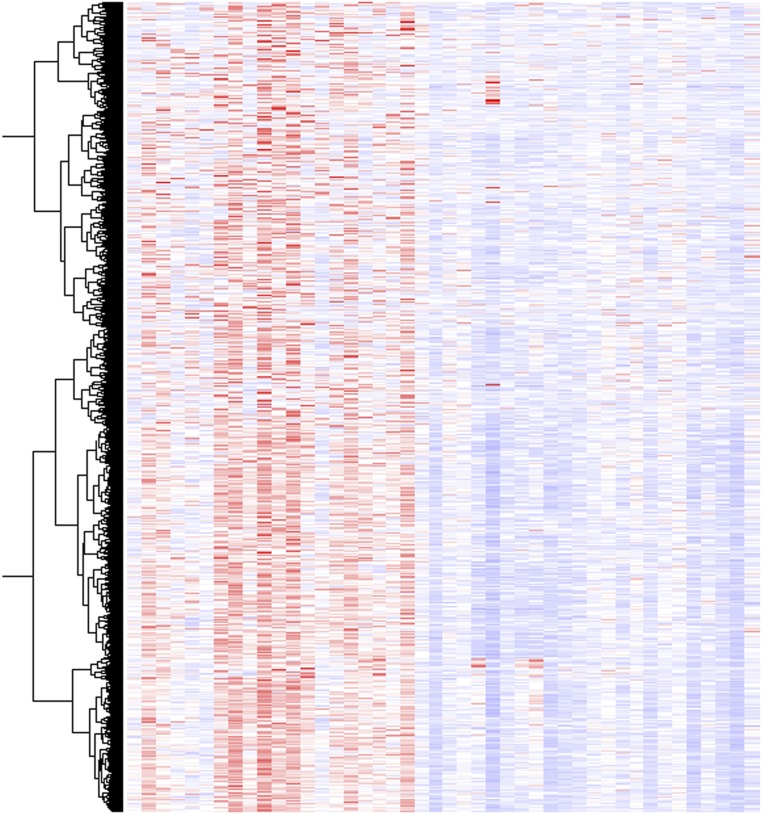

Fig. S2.

RNA sequencing using STRT protocol. RNA samples were placed in a 48-well plate in which a universal primer, template-switching helper oligos, and a well-specific 6-bp barcode sequence (for sample identification) were added to each well. Reverse transcription reagents (Thermo) and ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix I (Life Technologies) were added to generate first-strand cDNA. The synthesized cDNAs from the samples were then pooled into one library and amplified by single-primer PCR with the universal primer sequence. The resulting amplified library was then sequenced in three lanes using the Illumina HiSEq 2000 instrument. Gene expression analysis was as follows: Data processing of the sequenced RNA libraries was performed using the STRTprep pipeline (https://github.com/shka/STRTprep). The reads were demultiplexed into individual samples using the sample-specific barcodes, mapped to the human genome assembly hg19/GRCh37 with RefSeq annotations using Bowtie, and assembled into transcript regions using TopHat2.

The most down-regulated genes were as follows: (i) glutathione peroxidase 3, a gene that protects against oxidative stress; (ii) the protease inhibitors EXPI, WFDC3, and cystatin c; (iii) seminal vesicle secreted protein; and (iv) tumor-suppressive genes T-cadherin (cadherin 13) and caveolin-1 (Table 1 and Fig. S2).

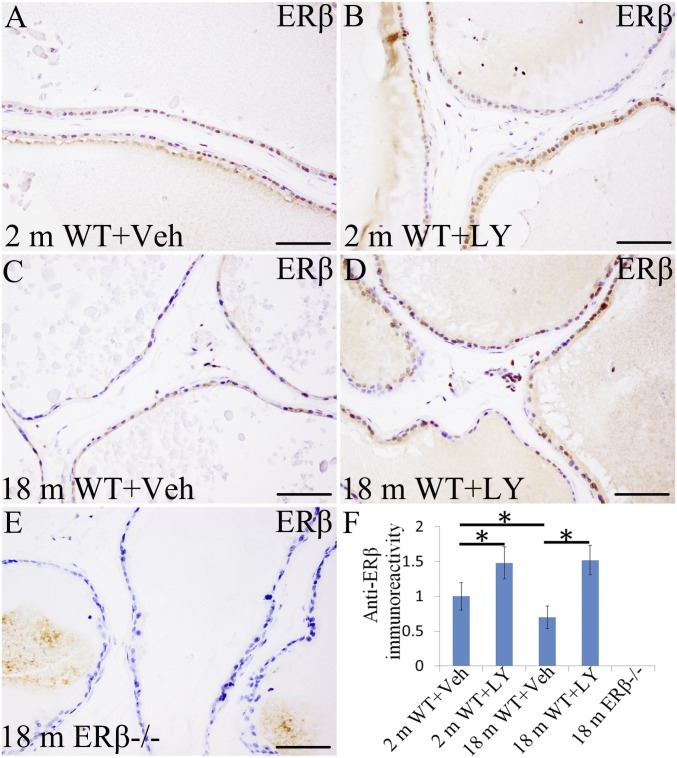

ERβ Agonist Increases Expression of ERβ in the Mouse VP.

LY3201 exposure resulted in an increase in ERβ expression in the luminal epithelium of the VP, in the stroma, and in the lymphocytes in the extracellular matrix. Induction was evident in mice at 2 mo of age (Fig. 1 A, B, and F) and was very pronounced in mice at 18 mo of age (Fig. 1 C, D, and F), at which time the number of epithelial cells expressing ERβ in WT prostate was markedly lower than that in 2-mo-old mice (Fig. 1 A, C, and F). Down-regulation of ERβ expression with age suggests that the aging prostate may be more susceptible to diseases related to excessive AR signaling. ERβ was not detectable in ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Up-regulation of ERβ expression in VP epithelium upon treatment with LY3201. (A and B) From 2-mo-old mice. (C and D) From 18-mo-old mice. (B, D, and F) In both 2-mo-old mice and 18-mo-old mice, LY3201 up-regulated ERβ expression (*P < 0.05). (E) Absence of ERβ in ERβ−/− mouse VP. (Scale bars: A–E, 100 μm.)

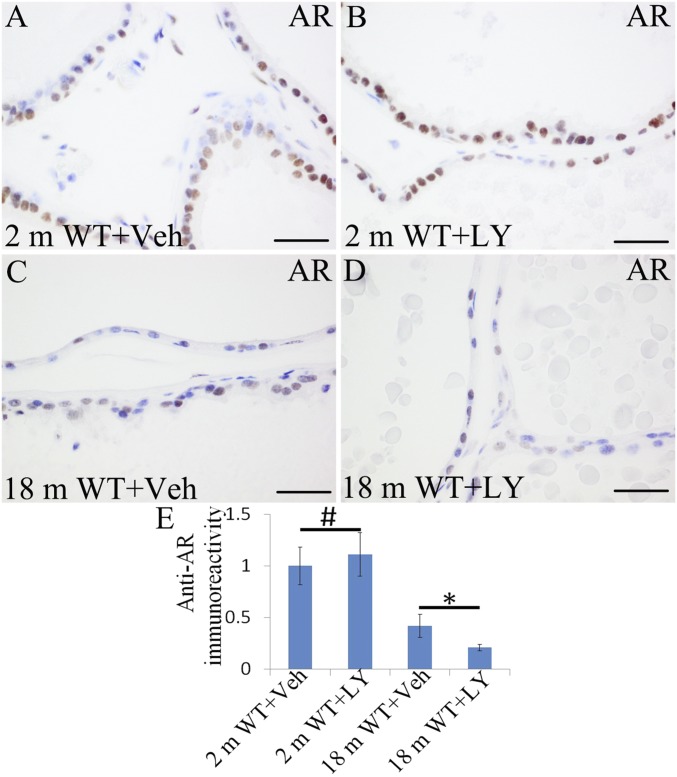

ERβ Agonist Inhibits AR Expression in VP of Aged Mice.

In previous studies, we showed that expression of AR was increased in 6-mo-old and 12-mo-old ERβ−/− mice (13). LY3201 treatment did not cause a change in AR expression in 2-mo-old mice (Fig. 2 A, B, and E). However, in 18-mo-old mice, AR expression was reduced by LY3201 (Fig. 2 C, D, and E). Overall, LY3201 administration resulted in reduction in AR signaling in old mice, and loss of ERβ resulted in increased AR signaling. It was recently reported that the nuclear receptor RORc recruits coactivators to the AR promotor and is a driver of AR (31). With RNA-Seq, we found that RORc mRNA was up-regulated sevenfold in ERβ−/− mice (Table 1). With immunohistochemistry, we found that there was very little expression of RORc in 2-mo-old mouse VP (Fig. 3 A, B, and E). Expression increased with age, and, in 18-mo-old mice, there was high nuclear expression in the epithelium of the VP. A 3-d exposure to LY3201 resulted in a marked down-regulation of RORc expression in the VP (Fig. 3 C, D, and E). Thus, ERβ down-regulates RORc.

Fig. 2.

Down-regulation of AR expression in old mouse VP by LY3201 treatment. (A and B) From 2-mo-old mice. (C and D) From 18-mo-old mice. (A, B, and E) LY3201 treatment did not change AR expression in 2-mo-old mice (#P > 0.05). (C, D, and E) In 18-mo-old mice, LY3201 treatment down-regulated AR expression (*P < 0.05). (Scale bars: A–D, 50 μm.)

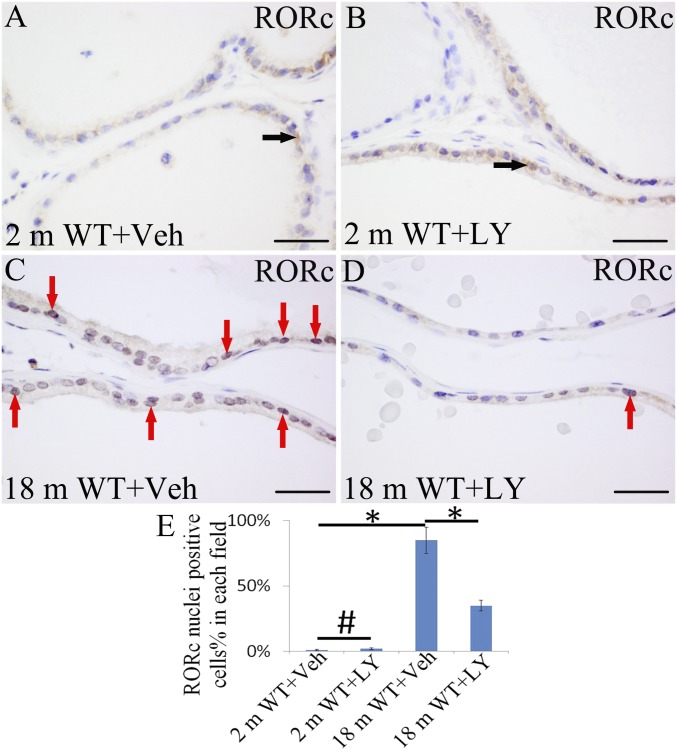

Fig. 3.

Effects of LY3201 on expression of RORc in mouse VP. (A) In vehicle-treated 2-mo-old mouse VP, very low expression of RORc was found in cytoplasm (black arrows). (B and E) Expression of RORc was unchanged by exposure to LY3201 (#P > 0.05). (C) There was strong nuclear expression of RORc in the epithelium of the VP in 18-mo-old mice (red arrows). (D and E) RORc expression was markedly down-regulated by treatment with LY3201 (#P > 0.05, *P < 0.05). (Scale bars: A–D, 50 μm.)

ERβ Agonist Up-Regulates DACH1 Expression.

DACH1 is a corepressor of ERα and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), as well as AR (32–34). It reduces the transcriptional activity of both normal AR and mutated AR found in CRPCa (32). Its regulation is a potentially useful target for treatment of both primary and metastatic PCa. Immunostaining for DACH1 revealed that, in WT mice, there was a clear nuclear staining in the VP epithelium (Fig. 4 A and C). In 2-mo-old VP, there was no significant change of DACH1 by exposure to LY3201 (Fig. 4 B and F). However, in 18-mo-old mice, treatment with LY3201 caused up-regulation of DACH1 (Fig. 4 D and F). DACH 1 expression in the epithelium of the VP was maintained in the ERβ−/− mouse (Fig. 4E), indicating that ERβ is not the only regulator of DACH1.

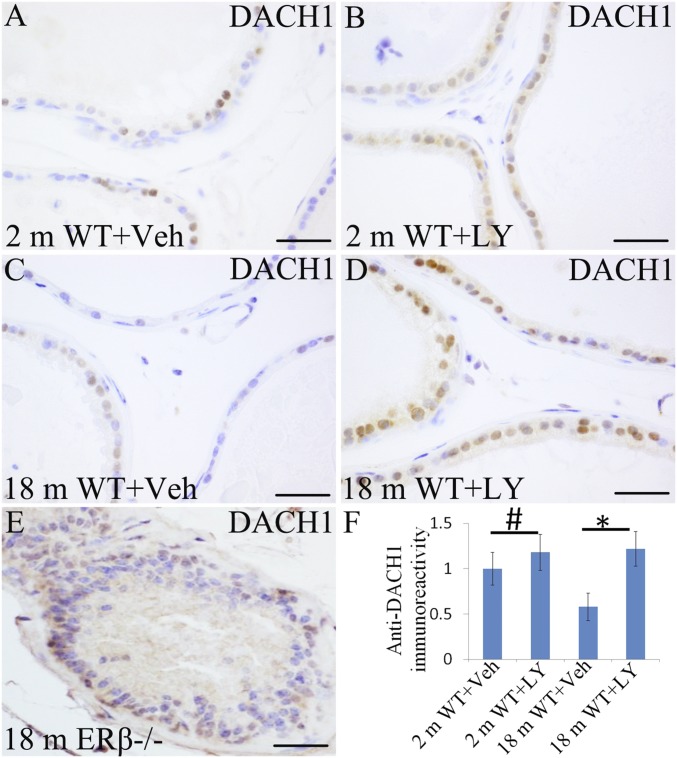

Fig. 4.

Alteration of DACH1 expression with ERβ agonist treatment. (A and C) DACH1 was expressed in epithelial cells. (B and F) There was no significant change of DACH1 in 2-mo-old VP by exposure to LY3201 (#P > 0.05). (D and F) DACH1 expression was increased significantly by LY3201 in18-mo-old mouse VP (*P < 0.05). (E) Scattered expression of DACH1 and hyperplastic epithelium in ERβ−/− mouse VP at 18 mo of age. (Scale bars: A–D, 50 μm.)

ERβ Agonist Mediates Nuclear Transport of PTEN.

Studies in the HC11 breast cell line have previously reported that the tumor suppressor gene PTEN is an ERβ-regulated gene (35). Here, we confirmed that PTEN is down-regulated in the VP of ERβ−/− mice (Fig. 5E). In addition to its well-characterized role in regulating AKT signaling at the cell membrane, PTEN is also expressed in the cell nucleus, where it exerts powerful antiproliferative actions (36). There was cytoplasmic staining, and a few nuclei were positive for PTEN in WT mouse VP (Fig. 5 A and C). LY3201 treatment increased PTEN expression and markedly increased its presence in nuclei (Fig. 5 B, D, and F).

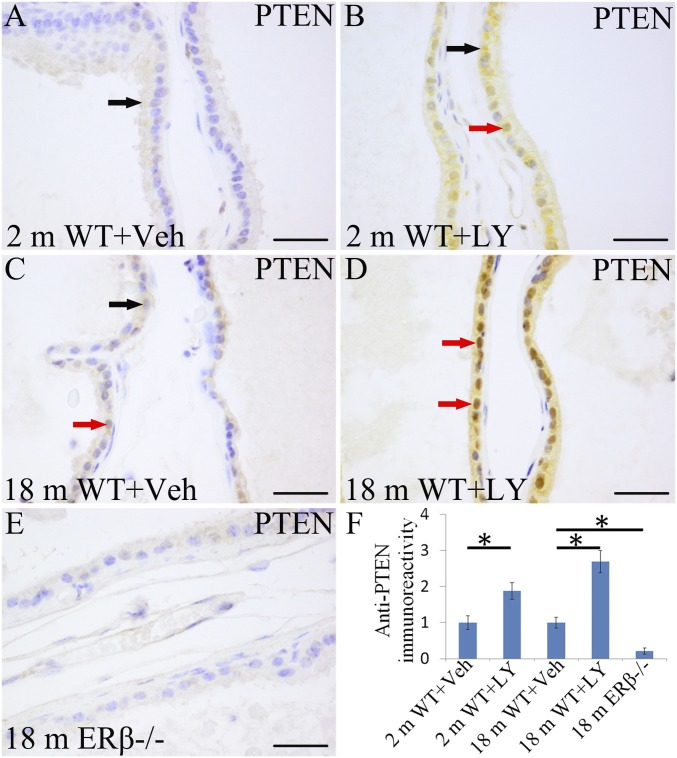

Fig. 5.

Increase in nuclear PTEN upon treatment with LY3201. PTEN can be detected in both cytoplasm (black arrow) and nucleus (red arrow). (A and C) There was cytoplasmic PTEN (black arrow) expression in the vehicle-treated WT mice with few positive nuclei (red arrow). (B, D, and F) LY3201 increased PTEN nuclear expression in both 2-mo-old and 18-mo-old mouse VP (*P < 0.05). (E) PTEN expression was extremely low in ERβ−/− mouse VP at 18 mo of age. (Scale bars: A–E, 50 μm.)

ERβ Agonist Increases T-Cadherin Expression.

T-cadherin (cadherin-13, CDH13), which functions as a tumor suppressor and is decreased in human PCa (37), was sevenfold down-regulated according to RNA-Seq (Table 1) in ERβ−/− mouse prostate. It was well-expressed in the WT mouse VP (Fig. 6 A and C). LY3201 treatment increased its expression, especially in 18-mo-old mouse VP (Fig. 6 B, D, and F). It was significantly reduced in the ERβ−/− mouse VP (Fig. 6E).

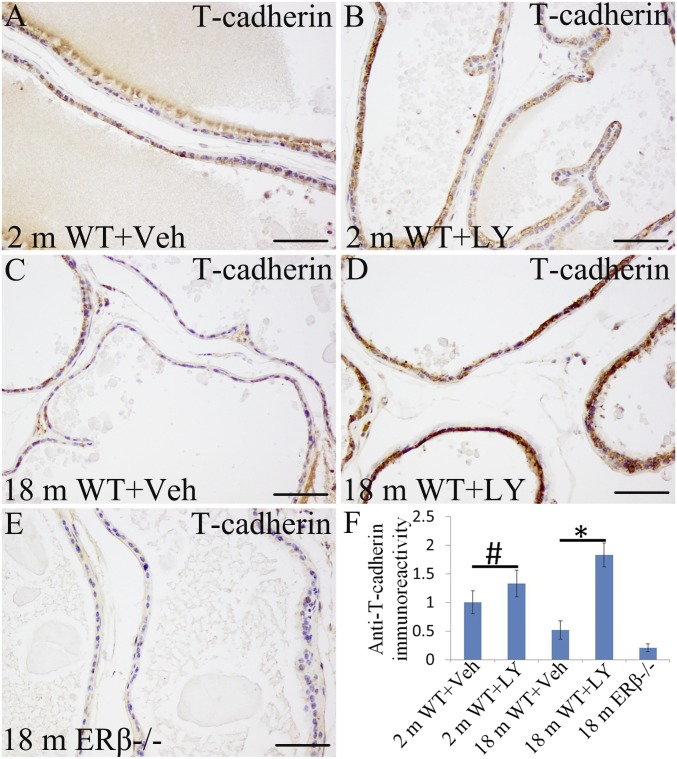

Fig. 6.

Increased expression of T-cadherin by LY3201 in mouse VP. (A and C) T-cadherin was expressed nicely in epithelial cells. It was decreased with age. (B and F) Expression of T cadherin was unchanged in 2-mo-old mice by exposure to LY3201 (#P > 0.05). (D and F) T-cadherin expression was increased by LY3201 in VP of 18-mo-old mice (*P < 0.05). (E) T-cadherin expression was low in ERβ−/− mouse VP at 18 mo of age. (Scale bars: A–E, 100 μm.)

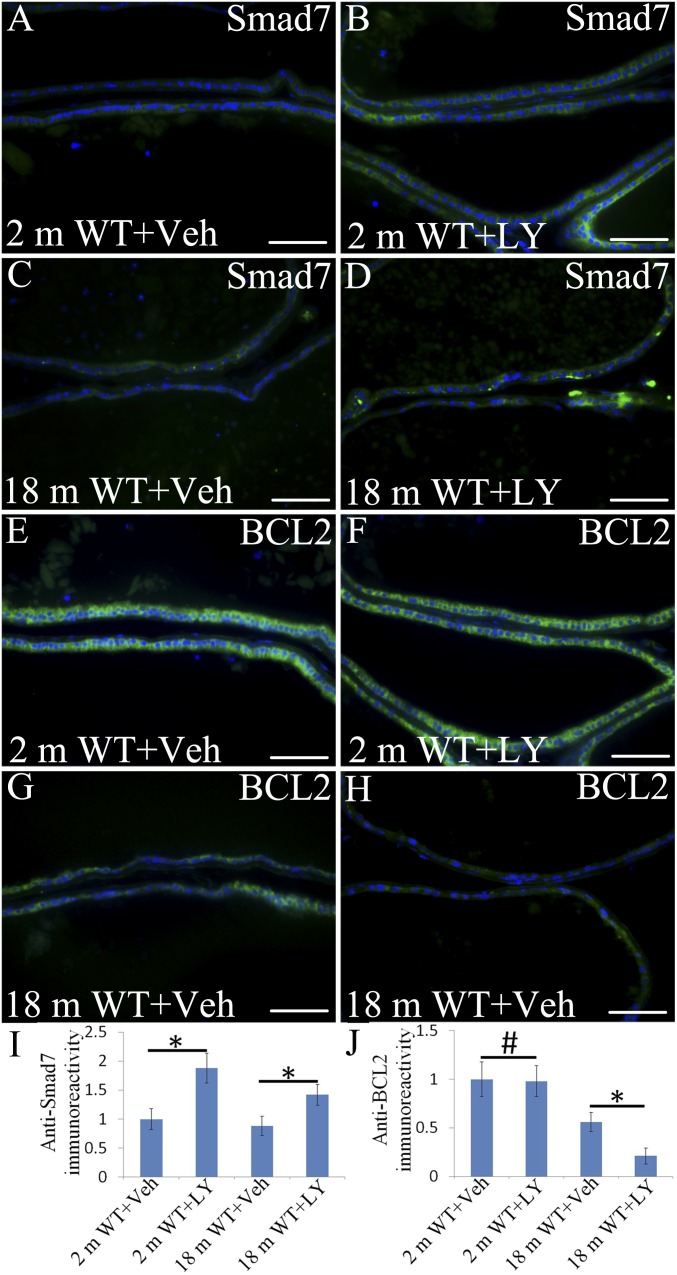

ERβ Agonist Modulates TGFβ Signaling.

RNA-Seq revealed that ERβ regulates multiple pathways that influence TGFβ signaling, but the overall impact of loss of ERβ on TGFβ signaling remains to be understood. Regulation of genes like TGFβ with widespread effects on proliferation and apoptosis in multiple cells is influenced by several signaling pathways, including estrogen, Notch, and SMAD. Smad7, an inhibitor of TGFβ signaling, was fivefold down-regulated in the ERβ−/− mouse VP. Smad7 was significantly increased in both 2-mo-old mouse VP and 18-mo-old mouse VP treated by ERβ agonist (Fig. 7 A, B, C, D, and I). Thus, ERβ is a suppressor of TGFβ signaling.

Fig. 7.

Alteration of Smad7 expression and BCL2 in VP epithelium upon LY3201 treatment. (A and C) Smad7 staining was weak in the epithelium of 2-mo-old and 18-mo-old vehicle-treated mice. (B, D, and I) Smad7 was strongly expressed in the cytoplasm of LY3201-treated mice both at 2 and 18 mo of age (*P < 0.05). (E and G) BCL2 was well-expressed in vehicle-treated mice at both 2 and 18 mo of age. (F and J) There was no change of BCl2 expression in 2-mo-old mice after exposure to LY3201(#P > 0.05). (H and J) There was a marked reduction of BCl2 expression in 18-mo-old mice after being treated by LY3201 (*P < 0.05). (Scale bars: A–H, 50 μm.)

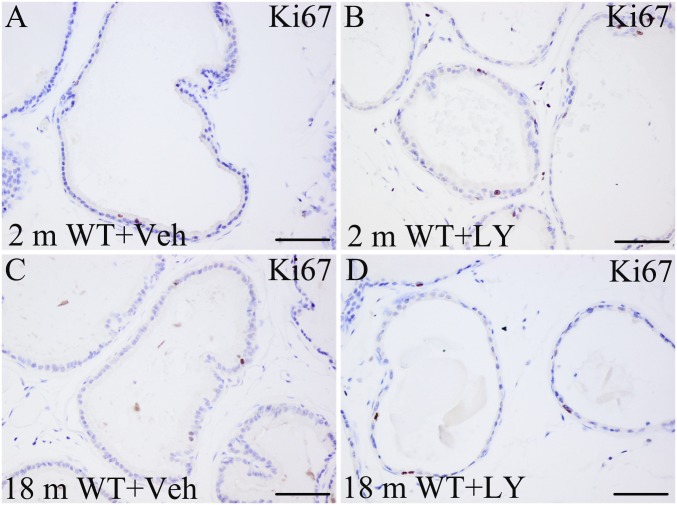

Bcl2 is a well-characterized suppressor of apoptosis. LY3201 treatment decreased expression of Bcl2 in the epithelium of the aging mouse VP (Fig. 7 E, F, G, H, and J). The effect of LY3201 on proliferation in the mouse VP was evaluated by Ki67 immunohistochemistry. There was no measurable increase in the number of Ki67-positive cells after treatment with LY3201 (Fig. S3).

Fig. S3.

No increase in the number of Ki67-positive cells upon LY3201-treatment. Ki67 immunostaining was used to label proliferation of epithelial cells located in ventral prostate ducts. (A and C) The proliferation rate of the prostatic epithelium is very low, and few Ki67-positive cells were detectable in both 2-mo-old and 18-mo-old mice treated with vehicle. (B and D) The number of Ki67-positive cells was similar after vehicle treatment and LY3201 treatment. (Scale bars: 100 μm.)

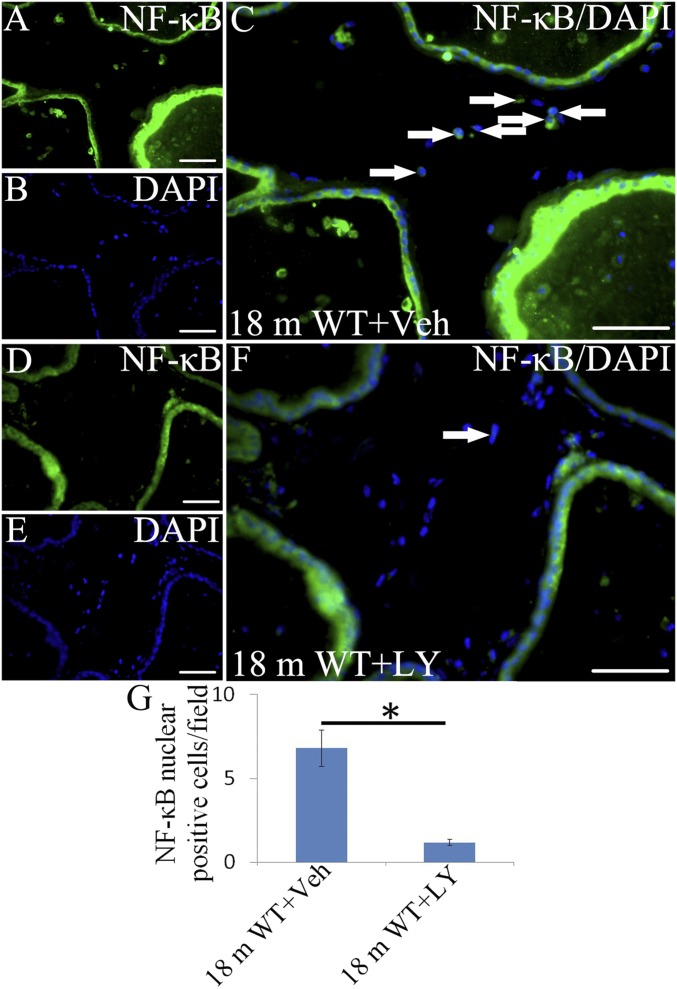

ERβ Agonist Reduces Activated NFκB and Cytokines in the VP.

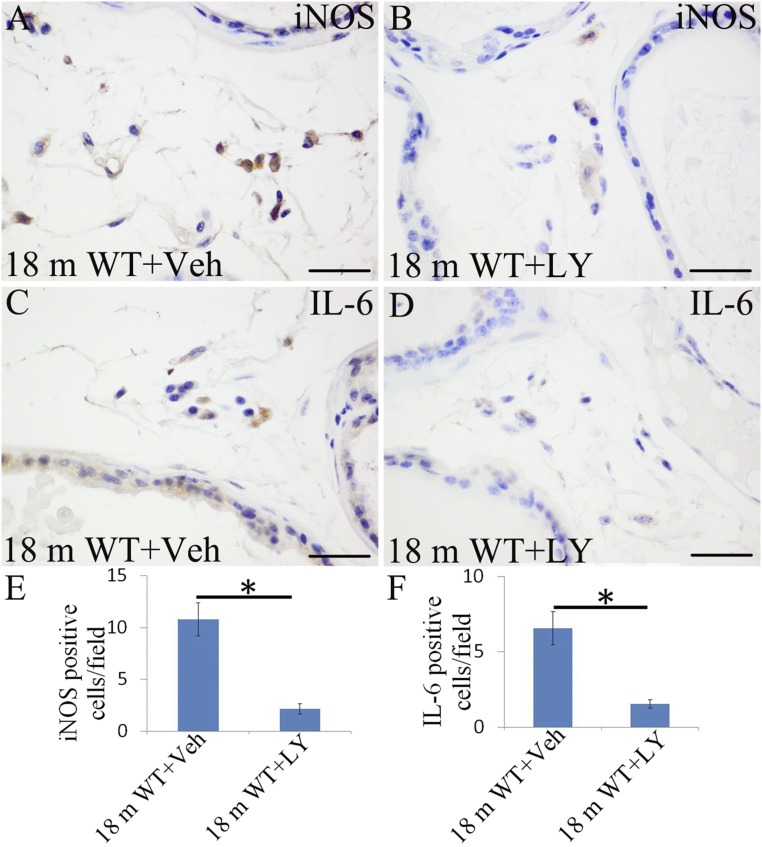

ERβ has antiinflammatory actions, and ERβ agonist has been used to prevent inflammation in a rat model of inflammatory bowel disease (21, 22) and to repress activation of microglia in the central nervous system (CNS) (38). LY3201 administration resulted in a marked down-regulation of activated NFκB in the VP of 18-mo-old mice (Fig. 8 C, F, and G). In addition, expression of the proinflammatory cytokine IL6 and iNOS was reduced in immune cells within the VP stroma (Fig. S4).

Fig. 8.

Down-regulation of activated NFκB by LY3201. (A and C) There was both cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of NFκB (white arrows) in vehicle-treated mice at 18 mo of age. (D, F, and G) In LY3201-treated mice at 18 mo of age, there was much less NFκB in the nucleus, and cytoplasmic staining was reduced as well (*P < 0.05). (B and E) DAPI counterstaining. (Scale bars: A–F, 50 μm.)

Fig. S4.

Inhibition of iNOS and IL-6 by LY3201. (A and C) Both iNOS and IL-6 expression in vehicle-treated mice at 18 mo of age. (B, D, E, and F) There was a sharp decrease of iNOS and IL-6 expression in LY3201-treated mice at 18 mo of age (*P < 0.05). (Scale bars: A–D, 50 μm.)

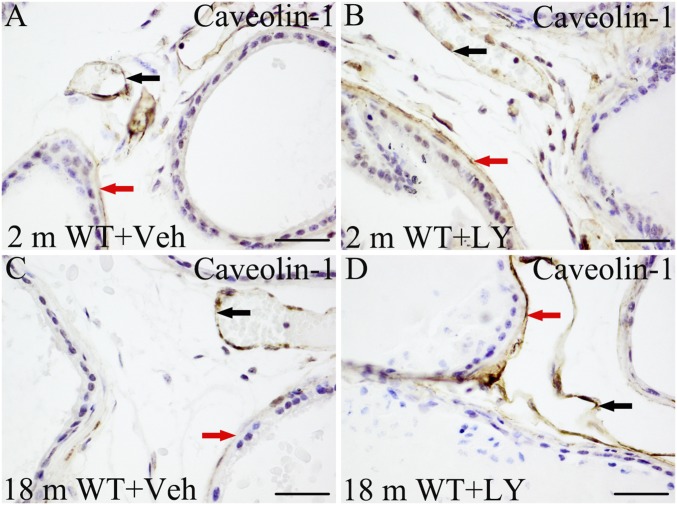

ERβ Agonist Up-Regulates Stromal Caveolin-1.

Increased expression of stromal caveolin-1 has been reported to protect against invasion of PCa (39). In the VP, caveolin-1 was expressed in the stroma surrounding the epithelial ducts and at the plasma membranes of endothelial cells. We demonstrated that, after 3 d of exposure to LY3201, there was a marked increase in stromal caveolin-1. The treatment did not change caveolin-1 in endothelial cells (Fig. S5).

Fig. S5.

Induction of stromal caveolin-1 by LY3201. (A and B) From 2-mo-old mice. (C and D) From 18-mo-old mice. (B and D) Caveolin-1 expression in the stroma (red arrow) was markedly increased by LY3201. No significant change of caveolin-1 in endothelial cells (black arrow). (Scale bars: 50 μm.)

Discussion

Since its cloning in 1996 from a rat cDNA prostate library (7), we have hypothesized that ERβ could be a major player in protecting against development and/or progression of PCa. In the present study, RNA sequencing allowed us to confirm a key role for ERβ in gene regulation in the mouse VP, and immunohistochemistry confirmed that gene expression does indeed translate into protein expression. The differences in gene expression between WT and ERβ−/− mice and between untreated and ERβ-agonist–treated mice confirmed the role for ERβ in regulating genes involved in prostatic growth, differentiation, inflammation, and invasiveness of cancer. In addition to well-known genes, such as protease inhibitors, and genes involved in inflammation and apoptosis, the present studies revealed ERβ regulation of tumor repressor genes PTEN, T-cadherin13, DACH1, and stromal caveolin-1.

Much more time and effort is needed to fully evaluate the physiological roles of ERβ in the prostate. Several genes important in prostate functions identified by RNA-Seq were ERβ-regulated but remain to be studied. These included the endoplasmic reticulum receptor Ssr3; the transcription repressor Zbtb38; the regulator of prostate metastasis to bone, osteopontin; S100A11; matrix gla protein; several proteases, such as SH3BGRL; and the structural components of E3 ubiquitin ligase complex Cul1.

Of the genes identified by RNA-seq that were followed up by immunohistochemistry, PTEN, T-cadherin, Smad7, and caveolin1 were confirmed to be up-regulated by LY3201, and NFκB, iNOS, IL-6, RORc, and Bcl2 were confirmed to be repressed by LY3201.

LY3201 was very effective in facilitating nuclear transport of PTEN. Nuclear transport of PTEN is regulated by ubiquitination. The E3 ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 negatively regulates PTEN protein levels through poly-ubiquitination and proteolysis in carcinomas of the prostate (40). Two ubiquitin ligases, UBE2E2 and NEDD4, and the ligase modulator Ndfip1 (NEDD4 and PTEN-interacting protein) participate in PTEN ubiquitination (41). NEDD4 was increased fourfold in the VP of ERβ−/− mice, suggesting that ERβ is a repressor of NEDD4 and by this repression may be a facilitator of PTEN transport into the nucleus. Nuclear PTEN offers a possible explanation for the antiproliferative actions of ERβ in the prostate.

T-cadherin (also called cadherin 13) is a newly characterized member of the cadherin family whose expression is decreased in several human cancers (37). It is a tumor suppressor gene responsible for cell recognition and adhesion. Its regulation by ERβ has not previously been reported. We found that T-cadherin was down-regulated in ERβ−/− prostate and that ERβ agonist treatment of WT mice increased expression of T-cadherin. This result indicates that ERβ may suppress cancer by up-regulating T-cadherin.

High levels of TGFβ correlate with a poor prognosis for patients with PCa (42). TGFβ function changes from inhibition of proliferation to induction of proliferation during development of cancer. TGFβ signals through type I and type II serine/threonine kinase receptors, which stimulate the phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3, and promotes their association with Smad4, which regulates expression of the inhibitory Smad, Smad7. The down-regulation of Smad7 by ERβ agonist suggests that TGFβ signaling is overactive in the absence of ERβ. Overactivity of TGFβ signaling is accompanied by increased expression of the TGFβ-regulated gene NUPR1 (nuclear protein 1, transcriptional regulator), which is associated with progression and metastasis (43).

Regulation by ERβ of PTEN, NFκB, and TGFβ suggests wide-spread effects of this receptor in cells in which it is expressed. ERβ is not ubiquitously expressed. In addition to the prostate epithelium and stroma, ERβ is expressed in several organs where it has profound physiological effects: to name a few, the immune system (44), the sympathetic nervous system (45), in blood vessels where its loss leads to hypertension (46), the urinary bladder where its loss leads to interstitial cystitis (47), and in the lung where its loss leads to general hypoxia because of a decrease in elasticity (48).

Recently, LY500307, a selective ERβ agonist, was tested in men for its effect on symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). The results were disappointing, and the study was terminated (49). LY500307 is a close relative of LY3201, and our results with LY3201 suggest a role in prevention and progression rather than treatment of symptoms. ERβ regulates TGFβ1 signaling. TGFβ causes differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and, through this mechanism, is thought to be involved in development of BPH (50, 51). In addition, development of BPH is related to inflammation, and ERβ has powerful antiinflammatory actions by down-regulating activated NFκB, iNOS, IL-6, and CXCL14, -16, and -17. Cytokines stimulate production of chemokines by stromal cells, leading to proliferation and development of BPH (52). These two pathways (TGFβ and NFκB) regulated by ERβ suggest that ERβ ligands should be effective in preventing development of BPH, but perhaps not in the treatment of BPH.

Treatment with ERβ agonists does not cause chemical castration because ERβ is not expressed in the pituitary and does not influence gonadotropin secretion from the pituitary. In addition, the antiinflammatory actions of ERβ ligands may be useful in treatment of prostatitis, a painful, distressing condition for which there is no adequate treatment. ERβ agonists have the advantage over glucocorticoids, the most powerful and effective antiinflammatory agents available, because they do not cause bone loss, a severe side effect of use of glucocorticoids.

Late stage PCa can be treated by androgen deprivation, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. However, the effect of these treatments is temporary, and, after 2 y, CRPCa, a lethal disease, emerges (53). The data presented herein reveal that ERβ may be a target worthy of consideration for treating early stage prostate cancer to prevent progression to more dangerous stages. ERβ modulated AR signaling by repressing AR coactivators (such as RORc) and increasing AR corepressors (such as DACH1). Thus, stimulating ERβ will repress AR signaling without changing androgen levels and without chemical castration.

Even though our main focus is on halting progression of PCa, it is possible that ERβ agonists may have a role in metastatic CRPCa, a lethal disease that is driven by AR (54). Our results demonstrated that AR signaling, whether androgen-dependent or independent, can be inhibited by ERβ. One study has reported that ERβ expression is increased once the cancer has metastasized (9, 12). Although it is difficult to understand why there would be ERβ in a highly proliferating disease, this possibility has to be examined further. It is possible that there is no endogenous ligand present because androgen ablation will lead to the absence of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) and its metabolite, 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol (3βAdiol), the endogenous ERβ ligand in the prostate (4). If there is absence of an endogenous ERβ ligand, ERβ agonists should be useful in treating metastatic PCa.

Overall, our data confirm a key role for ERβ in prostatic homeostasis and suggest that ERβ agonists should be useful in controlling prostate cancer, BPH, and prostatitis.

Materials and Methods

RNA Sequencing Using Single Cell-Tagged Reverse Transcription Protocol.

RNA (10 ng) was taken from VP of ERβ−/− and WT mice and processed using a variation of the highly multiplexed single cell-tagged reverse transcription (STRT) RNA sequencing protocol (55). Briefly, RNA samples were placed in a 48-well plate in which a universal primer, template-switching helper oligos, and a well-specific 6-bp barcode sequence (for sample identification) were added to each well (56). Reverse transcription reagents (Thermo) and ERCC RNA Spike-In Mix I (Life Technologies) were added to generate first-strand cDNA. The synthesized cDNAs from the samples were then pooled into one library and amplified by single-primer PCR with the universal primer sequence. The resulting amplified library was then sequenced in three lanes using the Illumina HiSEq 2000 instrument.

Gene Expression Analysis.

Data processing of the sequenced RNA libraries was performed using the STRTprep pipeline (https://github.com/shka/STRTprep). Briefly, the reads were demultiplexed into individual samples using the sample-specific barcodes, using Bowtie, and assembled into transcript regions using TopHat2 . For quality control, samples with low read counts (<x reads), high redundancy (>x), shallow spike-in counts (<x reads), low spike-in map rate (<x%), and low map rate to 5′-end of genes (<x%) were excluded from subsequent analyses. The read counts were normalized to relative amounts compared with total spike-in counts. Differential expression analysis was performed using SAMstrt (55). Variation caused by technical noise was estimated from technical replicates using a generalized linear model with a gamma distribution, as described (57). In addition to differential expression significance between control and treated samples, only transcripts with more biological variation than the background technical noise were considered as significant.

Materials, Animals, and Tissue Preparation.

The ERβ agonist LY3201 [(3aS,4R,9bR)-2,2-difluoro-4-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3,3a,4,9b-tetrahydro-1H-cyclopenta[c]chromen-8-ol (CAS 787621-78-7)] was a gift from Eli Lilly. The animal studies were approved by the Stockholm South ethical review board and the local Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee for animal experimentation (University of Houston animal protocol 09-036). Twenty C57BL/6 mice were divided randomly into the following two groups: (i) treated with vehicle (n = 10) or (ii) treated with LY3201 (n = 10). LY3201 was used as pellets (0.04 mg/d), which were made by Innovative Research of America, and implanted on the lateral side of the neck between the ear and the shoulder. The pellet is made of a matrix fused with an active product. The ingredients were as follows: cholesterol, cellulose, lactose, phosphates, and stearates. The mice were treated by inserting pellets (vehicle or LY3201) 3 d before euthanizing. Mice were housed in a room of standard temperature (22 ± 1 °C) with a regular 12-h light, 12-h dark cycle and given free access to water and standard rodent chow. All mice were terminally anesthetized by CO2 and transcardially perfused with 1× PBS, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4). Prostates were dissected and postfixed in the same fixative overnight at 4 °C. After fixation, prostates were processed for paraffin sections (5 μm).

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated through graded alcohol, and processed for antigen retrieval by boiling in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 12 to 15 min in PT module. Sections were incubated in 0.3% H2O2 in 50% methanol for 30 min at room temperature to quench endogenous peroxidase. To block nonspecific binding, sections were incubated in 3% BSA for 30 min, and then a biotin blocking system (Dako) was used to block endogenous biotin. Sections were then incubated with anti-ERβ (1:100; made in our laboratory), anti-AR (1:100; Abcam), anti-RORc (1:200; Abcam), anti-DACH1 (1:500; Abcam), anti-PTEN (1:100; Abcam), anti–T-cadherin (1:400; Santa Cruz Technology), anti-iNOS (1:100; Abcam), anti-IL6 (1:100; Abcam), anti-Ki67 (1:500; Abcam), and anti–caveolin-1 (1:500; Abcam) at 4 °C after blocking nonspecific binding in 3% BSA. BSA replaced primary antibodies in negative controls. After washing, sections were incubated with HRP polymer kit (GHP516; Biocare Medical) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride as the chromogen. For immunofluorescence, steps for quenching of endogenous peroxidase and blocking of endogenous biotin were omitted. Sections were incubated overnight with anti–NF-κB (1:200; Abcam), anti-Smad7 (1:100; Santa Cruz Technology), anti-Bcl2 (1:100; Abcam) at 4 °C after blocking nonspecific binding in 3% BSA. Primary antibodies were detected with donkey anti-goat FITC (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch), donkey anti-rabbit FITC (1:400; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and donkey anti-goat FITC (1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were later counterstained with Vectashield mounting medium containing 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector) to label nuclei. There were five mice in each group. We stained every fifth slide from 25 consecutive slices: i.e., five slices from each mouse. Two 400-magnification fields were checked in each slice for immunoreactivity; therefore, ten fields from each mouse were checked.

Data Analysis.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD; statistical comparisons were made by using a one-way ANOVA followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Robert A. Welch Foundation Grant E-0004, Eli Lilly, Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Grants HIRP100680 and RP110444, and the Swedish Cancer Society.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1702211114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Anantharaman A, Friedlander TW. Targeting the androgen receptor in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer: A review. Urol Oncol. 2016;34:356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuda CS, Brawer MK. Update: Prostate cancer. Compr Ther. 1990;16:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muthusamy S, et al. Estrogen receptor β and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 6, a growth regulatory pathway that is lost in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:20090–20094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117772108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weihua Z, Lathe R, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. An endocrine pathway in the prostate, ERbeta, AR, 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol, and CYP7B1, regulates prostate growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13589–13594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162477299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dey P, Ström A, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor β upregulates FOXO3a and causes induction of apoptosis through PUMA in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33:4213–4225. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain S, et al. APC BioResource Estrogen receptor β activation impairs prostatic regeneration by inducing apoptosis in murine and human stem/progenitor enriched cell populations. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horvath LG, et al. Frequent loss of estrogen receptor-beta expression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5331–5335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fixemer T, Remberger K, Bonkhoff H. Differential expression of the estrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) in human prostate tissue, premalignant changes, and in primary, metastatic, and recurrent prostatic adenocarcinoma. Prostate. 2003;54:79–87. doi: 10.1002/pros.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mak P, et al. ERbeta impedes prostate cancer EMT by destabilizing HIF-1alpha and inhibiting VEGF-mediated snail nuclear localization: Implications for Gleason grading. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torlakovic E, Lilleby W, Torlakovic G, Fosså SD, Chibbar R. Prostate carcinoma expression of estrogen receptor-beta as detected by PPG5/10 antibody has positive association with primary Gleason grade and Gleason score. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:646–651. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.124033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai JS, et al. Metastases of prostate cancer express estrogen receptor-beta. Urology. 2004;64:814–820. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imamov O, et al. Estrogen receptor beta regulates epithelial cellular differentiation in the mouse ventral prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9375–9380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mewshaw RE, et al. ERbeta ligands. 3. Exploiting two binding orientations of the 2-phenylnaphthalene scaffold to achieve ERbeta selectivity. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3953–3979. doi: 10.1021/jm058173s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malamas MS, et al. Design and synthesis of aryl diphenolic azoles as potent and selective estrogen receptor-beta ligands. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5021–5040. doi: 10.1021/jm049719y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norman BH, et al. Benzopyrans are selective estrogen receptor beta agonists with novel activity in models of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6155–6157. doi: 10.1021/jm060491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norman BH, et al. Benzopyrans as selective estrogen receptor beta agonists (SERBAs). Part 4: Functionalization of the benzopyran A-ring. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:5082–5085. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paterni I, Granchi C, Katzenellenbogen JA, Minutolo F. Estrogen receptors alpha (ERα) and beta (ERβ): Subtype-selective ligands and clinical potential. Steroids. 2014;90:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paterni I, et al. Highly selective salicylketoxime-based estrogen receptor β agonists display antiproliferative activities in a glioma model. J Med Chem. 2015;58:1184–1194. doi: 10.1021/jm501829f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yonekubo S, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 1-benzylindane derivatives as selective agonists for estrogen receptor beta. Bioorg Med Chem. 2016;24:5895–5910. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris HA, et al. Evaluation of an estrogen receptor-beta agonist in animal models of human disease. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4241–4249. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cristofaro PA, et al. WAY-202196, a selective estrogen receptor-beta agonist, protects against death in experimental septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2188–2193. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227173.13497.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartman J, et al. Estrogen receptor beta inhibits angiogenesis and growth of T47D breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11207–11213. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ström A, et al. Estrogen receptor beta inhibits 17beta-estradiol-stimulated proliferation of the breast cancer cell line T47D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:1566–1571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308319100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodges-Gallagher L, Valentine CD, El Bader S, Kushner PJ. Estrogen receptor beta increases the efficacy of antiestrogens by effects on apoptosis and cell cycling in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109:241–250. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9640-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartman J, et al. Tumor repressive functions of estrogen receptor beta in SW480 colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6100–6106. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sareddy GR, et al. Selective estrogen receptor β agonist LY500307 as a novel therapeutic agent for glioblastoma. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24185. doi: 10.1038/srep24185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slusarz A, et al. Aggressive prostate cancer is prevented in ERαKO mice and stimulated in ERβKO TRAMP mice. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4160–4170. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krege JH, et al. Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15677–15682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morais-Santos M, et al. Changes in estrogen receptor ERβ (ESR2) expression without changes in the estradiol levels in the prostate of aging rats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, et al. ROR-γ drives androgen receptor expression and represents a therapeutic target in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:488–496. doi: 10.1038/nm.4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen K, et al. The endogenous cell-fate factor dachshund restrains prostate epithelial cell migration via repression of cytokine secretion via a cxcl signaling module. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1992–2004. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan W, et al. Epigenetic silencing of DACH1 induces the invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer by activating TGF-β signalling. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:2499–2511. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu K, Yuan X, Pestell R. Endogenous Dach1 in cancer. Oncoscience. 2015;2:803–804. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindberg K, Helguero LA, Omoto Y, Gustafsson JA, Haldosén LA. Estrogen receptor β represses Akt signaling in breast cancer cells via downregulation of HER2/HER3 and upregulation of PTEN: Implications for tamoxifen sensitivity. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R43. doi: 10.1186/bcr2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howitt J, et al. Ndfip1 represses cell proliferation by controlling Pten localization and signaling specificity. J Mol Cell Biol. 2015;7:119–131. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjv020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andreeva AV, Kutuzov MA. Cadherin 13 in cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:775–790. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu WF, et al. Targeting estrogen receptor β in microglia and T cells to treat experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3543–3548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300313110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Vizio D, et al. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 is associated with advanced prostate cancer, metastatic disease and epithelial Akt activation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2420–2424. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed SF, et al. The chaperone-assisted E3 ligase C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP) targets PTEN for proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15996–16006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.321083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, et al. Rab5 and Ndfip1 are involved in Pten ubiquitination and nuclear trafficking. Traffic. 2014;15:749–761. doi: 10.1111/tra.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niu Y, et al. Androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor and proliferator in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12182–12187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804700105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pommier RM, et al. The human NUPR1/P8 gene is transcriptionally activated by transforming growth factor β via the SMAD signalling pathway. Biochem J. 2012;445:285–293. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shim GJ, et al. Disruption of the estrogen receptor beta gene in mice causes myeloproliferative disease resembling chronic myeloid leukemia with lymphoid blast crisis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6694–6699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0731830100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miao YF, et al. An ERβ agonist induces browning of subcutaneous abdominal fat pad in obese female mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38579. doi: 10.1038/srep38579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu Y, et al. Abnormal vascular function and hypertension in mice deficient in estrogen receptor beta. Science. 2002;295:505–508. doi: 10.1126/science.1065250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Imamov O, et al. Estrogen receptor beta-deficient female mice develop a bladder phenotype resembling human interstitial cystitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9806–9809. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703410104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morani A, et al. Lung dysfunction causes systemic hypoxia in estrogen receptor beta knockout (ERbeta-/-) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7165–7169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602194103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roehrborn CG, et al. Estrogen receptor beta agonist LY500307 fails to improve symptoms in men with enlarged prostate secondary to benign prostatic hypertrophy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2015;18:43–48. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2014.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alonso-Magdalena P, et al. A role for epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the etiology of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2859–2863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812666106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hisataki T, et al. Modulation of phenotype of human prostatic stromal cells by transforming growth factor-betas. Prostate. 2004;58:174–182. doi: 10.1002/pros.10320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schauer IG, Rowley DR. The functional role of reactive stroma in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Differentiation. 2011;82:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wadosky KM, Koochekpour S. Molecular mechanisms underlying resistance to androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:64447–64470. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cornford P, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of relapsing, metastatic, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71:630–642. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katayama S, Töhönen V, Linnarsson S, Kere J. SAMstrt: Statistical test for differential expression in single-cell transcriptome with spike-in normalization. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:2943–2945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Islam S, et al. Quantitative single-cell RNA-seq with unique molecular identifiers. Nat Methods. 2014;11:163–166. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salway R, Wakefield J. Gamma generalized linear models for pharmacokinetic data. Biometrics. 2008;64(2):620–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]