Abstract

Importance

Medicare beneficiaries with cancer are at risk for financial hardship given increasingly expensive cancer care and significant cost sharing by beneficiaries.

Objectives

To measure out-of-pocket (OOP) costs incurred by Medicare beneficiaries with cancer and identify which factors and services contribute to high OOP costs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

We prospectively collected survey data from 18 166 community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries, including 1409 individuals who were diagnosed with cancer during the study period, who participated in the January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2012, waves of the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative panel study of US residents older than 50 years. Data analysis was performed from July 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Out-of-pocket medical spending and financial burden (OOP expenditures divided by total household income).

Results

Among the 1409 participants (median age, 73 years [interquartile range, 69-79 years]; 46.4% female and 53.6% male) diagnosed with cancer during the study period, the type of supplementary insurance was significantly associated with mean annual OOP costs incurred after a cancer diagnosis ($2116 among those insured by Medicaid, $2367 among those insured by the Veterans Health Administration, $5976 among those insured by a Medicare health maintenance organization, $5492 among those with employer-sponsored insurance, $5670 among those with Medigap insurance coverage, and $8115 among those insured by traditional fee-for-service Medicare but without supplemental insurance coverage). A new diagnosis of cancer or common chronic noncancer condition was associated with increased odds of incurring costs in the highest decile of OOP expenditures (cancer: adjusted odds ratio, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.55-2.23; P < .001; chronic noncancer condition: adjusted odds ratio, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.69-1.97; P < .001). Beneficiaries with a new cancer diagnosis and Medicare alone incurred OOP expenditures that were a mean of 23.7% of their household income; 10% of these beneficiaries incurred OOP expenditures that were 63.1% of their household income. Among the 10% of beneficiaries with cancer who incurred the highest OOP costs, hospitalization contributed to 41.6% of total OOP costs.

Conclusions and Relevance

Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental insurance incur significant OOP costs following a diagnosis of cancer. Costs associated with hospitalization may be a primary contributor to these high OOP costs. Medicare reform proposals that restructure the benefit design for hospital-based services and incorporate an OOP maximum may help alleviate financial burden, as can interventions that reduce hospitalization in this population.

This study uses data from the Heath and Retirement Study to measure out-of-pocket costs incurred by Medicare beneficiaries with cancer and identify which factors contribute to high out-of-pocket costs.

Key Points

Questions

What are the out-of-pocket (OOP) costs incurred by Medicare beneficiaries with cancer, and what factors and services drive these high OOP costs?

Findings

In this nationally representative panel study, Medicare beneficiaries with a new cancer diagnosis were vulnerable to high OOP costs depending on their supplemental insurance: beneficiaries without supplemental insurance incurred OOP expenditures that were a mean of 23.7% of their household income, with 10% incurring OOP costs that were 63.1% of their household income. Hospitalizations were a primary driver of these high OOP costs.

Meaning

Elderly patients with cancer need improved protection against costly hospitalizations.

Introduction

Among the 5 health conditions that contribute most to health care costs in the United States, per-person direct medical expenditures on cancer are the highest. Moreover, annual direct medical expenditures on cancer are projected to increase by nearly 40% from 2010 to 2020, largely owing to a combination of changing demographics, increased use of services, and expensive new treatments. As most new cancers and cancer-associated deaths occur in adults older than 65 years, much of this cost burden will be borne by Medicare, the federal health insurance program for the elderly and disabled.

However, traditional Medicare also requires considerable cost sharing from its beneficiaries and does not include an out-of-pocket (OOP) maximum. Although supplemental coverage through Medigap, employer-sponsored insurance, or Medicaid can minimize OOP costs, considerable heterogeneity exists in the design of benefits, placing seniors at variable financial risk. Medicare beneficiaries who obtain their benefits through a health maintenance organization (HMO) face similar variation in the design of benefits. Moreover, more than 4 million Medicare beneficiaries lack supplemental insurance altogether and may be particularly vulnerable following a major diagnosis, such as cancer. Indeed, reports have increasingly documented the adverse consequences of cancer on patients’ financial well-being, including depleted savings and even bankruptcy. Financial distress may also discourage use of effective services, including poor adherence to key anticancer therapies. Protecting patients against the “financial toxicity” of cancer has therefore become a central objective of the oncology community.

Ensuring the financial security of elderly patients with cancer requires an understanding of which patients experience high OOP costs and what services contribute to these costs. Prior work on this subject has been limited by older data and exclusion of Medicare beneficiaries who receive their benefits through an HMO, which now represents 30% of Medicare beneficiaries. In addition, there is limited information on the service categories that contribute to high OOP costs, and existing comparisons of OOP costs across disease types have included patients in a nursing home, whose high long-term care costs dwarf other cost categories.

We address these gaps by characterizing the distribution of OOP costs incurred by a nationally representative cohort of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. We also examine the variation in OOP costs based on types of supplemental insurance. Finally, we explore which services were primarily responsible for imposing significant financial burden on the beneficiaries who incurred the highest OOP costs.

Methods

Study Population

We analyzed survey data from the July 1, 2002, to December 31, 2012, waves of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a nationally representative, longitudinal panel study of US residents older than 50 years. The HRS is designed to collect detailed health, demographic, and financial information from its participants and includes data on their OOP medical expenditures. Approximately 20 000 participants are interviewed biennially, with response rates of more than 85% during the study period. Oral informed consent is obtained from participants as part of the HRS process. Our study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Institutional Review Board.

The population included community-dwelling HRS participants older than 65 years who were enrolled in either fee-for-service Medicare or obtained Medicare benefits through an HMO. Nursing home residents were excluded given their distinct patterns of resource use compared with community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. Participants with a new diagnosis of cancer were identified based on their first affirmative response to the following question: “Has a doctor ever told you that you have cancer or a malignant tumor, excluding minor skin cancer?” The reported date of diagnosis was also cross-referenced with survey administration dates to confirm the interval in which a cancer diagnosis was made. Subsequent surveys from patients newly diagnosed with cancer were excluded from the analysis except for the HRS exit interview, which was used to analyze the cost of end-of-life care. In addition, we used similar survey items to identify patients who were diagnosed with 1 of the 5 most common nonaccidental causes of mortality in the United States (ie, heart disease, lung disease, stroke, dementia, and type 1 or 2 diabetes).

OOP Expenditures

Our primary outcome of interest was the level of OOP expenditures incurred by HRS participants between survey administrations. Since 2002, the HRS has collected detailed data on OOP expenditures using the following cost categories: inpatient hospitalization, nursing home, clinic visits with a physician, dental care, outpatient surgery, prescription drugs, home health care, and other health services. More important, the HRS did not provide respondents with explicit instructions on the assignment to a specific cost category of radiation services, chemotherapy, or oral targeted anticancer agents.

For each cost category other than prescription drugs, HRS participants are asked, “About how much did you pay out of pocket for XX [since the last interview or in the last 2 years]?” For prescription drugs, participants are asked about OOP expenditures in the month prior to the interview. Median time between surveys was 2.0 years (interquartile range, 1.8-2.4 years). Out-of-pocket expenditures were normalized to an annual scale, and values were adjusted to 2012 dollars.

The HRS uses an innovative method of random entry bracketing, in which nonrespondents sequentially refine an estimated range of OOP expenditures (eAppendix in the Supplement). For participants reporting expenditures within a bracketed range, exact OOP expenditure values were imputed using a method developed by the RAND Corporation, as described elsewhere. Although 12 668 of the 61 339 responses (20.7%) that were provided with respect to OOP expenditures were not exact amounts, the bracketing approach minimized complete nonresponse to any item to less than 5%.

Income, Wealth, and Supplemental Insurance

Indexing OOP expenditures to financial well-being may allow for a better estimate of financial distress. We calculated financial burden as OOP expenditures divided by total household income. The HRS collects comprehensive data on household income and household wealth (eAppendix in the Supplement). Components of household income and wealth were summed for both the participant and spouse, if present. All income and wealth measures are reported in 2012 dollars.

To examine the association between participants’ OOP expenditures and insurance arrangements, participants were classified into 1 of 6 mutually exclusive insurance categories, which included 5 types of supplemental insurance arrangements for patients enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare, as well as a category for patients in a Medicare HMO. In order of an expectation of increased cost sharing, these insurance categories included Medicaid; Veterans Health Administration; Medicare HMO; employer-sponsored insurance, including retiree and spousal coverage; Medigap; and none. A simplified classification schema was also used in which the Medicaid and Veterans Health Administration categories were combined into the category of public supplemental insurance, and the employer-sponsored and Medigap categories were consolidated into private supplemental insurance.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed from July 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015. Baseline sociodemographic and health-associated characteristics were compared between patients with and without cancer using a 2-sample t test and χ2 test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. A multivariable generalized linear model was constructed to assess mean OOP expenditures using a log link function and gamma family distribution. Multivariable quantile regression was performed to assess the median and 90th percentile of OOP expenditures. Multivariable logistic regression was also performed to determine which factors were associated with incurring costs in the highest decile of OOP expenditures. Models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, marital status, geographic region, self-reported health, comorbidity, smoking status, wealth quartile, and type of supplemental insurance. In addition, we accounted for potential correlation within participant responses from multiple survey waves by clustering standard errors by participants’ unique identification number.

Out-of-pocket expenditures for HRS participants with cancer were compared with OOP expenditures among participants with other common disease types that contribute to mortality in the United States. Comparisons were repeated within patient subsets that were defined by type of supplemental insurance. A similar method was used for analyzing financial burden. In addition, the relative contribution of each OOP cost category to total OOP costs was examined.

The HRS selects its participants using a complex, multistage, area probability sampling design. Because the HRS oversamples African Americans and Hispanics, sampling weights are created such that the weighted HRS sample is representative of community-dwelling US households. We accounted for the complex sampling design by applying respondent-level sampling weights in all calculations.

Throughout the analysis, 2-sided significance testing was used, and P = .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata/IC software, version 10.0 (StataCorp).

Results

A total of 18 166 community-dwelling US residents older than 65 years participated in the HRS between 2002 and 2012 and were enrolled in fee-for-service Medicare or received Medicare benefits through an HMO. Participants completed a median of 3 survey waves (range, 1-6) and produced 61 339 observations.

During the study period, 1409 participants (7.8%) were newly diagnosed with cancer (Table 1). Median time from cancer diagnosis to survey completion was 1.2 years (interquartile range, 0.8-1.6 years). Compared with patients who did not have cancer, HRS participants who were newly diagnosed with cancer were more likely to be male (53.6% vs 43.4%; P < .001), white (90.5% vs 87.9%; P = .001), non-Hispanic (96.1% vs 93.2%; P < .001), married (63.2% vs 59.2%; P = .01), and report higher self-assessed health status (good to excellent health, 76.2% vs 61.4%; P < .001) despite more frequently indicating a history of heart (32.8% vs 30.1%; P = .05) or lung (14.9% vs 10.9%; P < .001) disease. Although patients with cancer generally belonged to higher wealth (third and fourth quartiles, 57.0% vs 48.8%; P = .001) and income quartiles (third and fourth quartiles, 53.6% vs 49.1%; P = .002), substantial heterogeneity in wealth and income was present. Patients with cancer who were in lower wealth and income quartiles more commonly had Medicaid coverage or lacked supplemental insurance and less commonly had employer-sponsored or Medigap supplemental insurance (P < .001 for all; eTable 1 in the Supplement) compared with patients with cancer who were in higher wealth and income quartiles.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristica | Valueb | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Cancer (n = 16 757) |

Newly Diagnosed Cancer (n = 1409) |

||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 73 (69-80) | 73 (69-79) | .14 |

| Female | 9484 (56.6) | 654 (46.4) | <.001 |

| Race | |||

| White | 14 730 (87.9) | 1275 (90.5) | .001 |

| Black | 1441 (8.6) | 110 (7.8) | |

| Other | 586 (3.5) | 24 (1.7) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1139 (6.8) | 55 (3.9) | <.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 9920 (59.2) | 891 (63.3) | .01 |

| Separated or divorced | 1659 (9.9) | 154 (10.9) | |

| Widowed | 4608 (27.5) | 333 (23.7) | |

| Single | 570 (3.4) | 31 (2.2) | |

| Self-reported health | |||

| Poor | 1509 (9.0) | 52 (3.7) | <.001 |

| Fair | 4951 (29.5) | 285 (20.2) | |

| Good | 5588 (33.3) | 440 (31.3) | |

| Very good | 3402 (20.3) | 363 (25.8) | |

| Excellent | 1307 (7.8) | 269 (19.1) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Lung disease | 1827 (10.9) | 210 (14.9) | <.001 |

| Heart disease | 5044 (30.1) | 462 (32.8) | .05 |

| Wealth quartilec | |||

| First | 4323 (25.8) | 245 (17.4) | .001 |

| Second | 4256 (25.4) | 361 (25.6) | |

| Third | 4140 (24.7) | 382 (27.1) | |

| Fourth | 4038 (24.1) | 421 (29.8) | |

| Income quartiled | |||

| First | 4290 (25.6) | 262 (18.6) | .002 |

| Second | 4240 (25.3) | 392 (27.8) | |

| Third | 4138 (24.7) | 369 (26.2) | |

| Fourth | 4089 (24.4) | 386 (27.4) | |

| Supplemental insurance | |||

| Medicaid | 1441 (8.6) | 111 (7.9) | .004 |

| Veterans Health Administration | 1005 (6.0) | 116 (8.2) | |

| Medicare HMO | 3301 (19.7) | 251 (17.8) | |

| Employer-sponsored | 4709 (28.1) | 391 (27.8) | |

| Medigap | 3754 (22.4) | 353 (25.1) | |

| None | 2547 (15.2) | 187 (13.3) | |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; HMO, health maintenance organization.

Some variables in the multivariable model are not listed here owing to table length, namely, geographic region, educational level, multiple comorbidities (hypertension, stroke, arthritis, psychiatric illness, and type 1 or 2 diabetes), and smoking status. No differences were seen in these variables between participants with and without cancer.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated.

Wealth quartiles: first, <$89 581; second, $89 582-$256 293; third, $256 294-$638 926; fourth, >$638 926.

Income quartiles: first, <$22 380; second, $22 381-$37 198; third, $37 199-$64 579; fourth, >$64 579.

Mean annual OOP expenditures was $3737 and financial burden was 11.4% for all HRS participants. The distributions of OOP expenditures and financial burden were right-skewed: at the 90th percentile, annual OOP expenditures were $8078 and financial burden was 29.6%. A new diagnosis of cancer or common chronic noncancer condition was associated with increased odds of incurring costs in the highest decile of OOP expenditures (cancer: adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.86; 95% CI, 1.55-2.23; P < .001; chronic noncancer condition: AOR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.69-1.97; P < .001) (Table 2) compared with other HRS participants. Likewise, HRS participants with private supplemental insurance, without supplemental insurance, or who obtained Medicare benefits through an HMO all had increased odds of incurring costs that were in the highest decile of OOP expenditures compared with participants with Medicaid or Veterans Health Administration coverage (Medicare HMO: AOR, 1.80; 95% CI, 1.55-2.08; P < .001; private supplemental: AOR, 2.38; 95% CI, 2.09-2.71; P < .001; and none: AOR, 2.86; 95% CI, 2.48-3.29; P < .001). Similar associations were seen with financial burden (Table 2).

Table 2. Variables Associated With High Out-of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Burden.

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Out-of-Pocket Expendituresa | P Value | High Financial Burden | ||

| Age, y [reference, <70] | ||||

| 70-80 | 0.98 (0.90-1.06) | .55 | 1.11 (1.02-1.21) | .02 |

| >80 | 1.16 (1.05-1.29) | .004 | 1.41 (1.27-1.56) | <.001 |

| Sex [reference, male] | ||||

| Female | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) | .004 | 1.30 (1.20-1.42) | <.001 |

| Race [reference, white] | ||||

| Black | 0.92 (0.81-1.03) | .15 | 1.25 (1.12-1.39) | <.001 |

| Other | 0.78 (0.61-1.01) | .06 | 0.90 (0.72-1.11) | .33 |

| Hispanic ethnicity [reference, no] | ||||

| Yes | 0.81 (0.68-0.96) | .02 | 1.19 (1.02-1.37) | .02 |

| Educational level [reference, less than high school] | ||||

| High school graduate | 1.00 (0.90-1.11) | .99 | 0.74 (0.68-0.82) | <.001 |

| Some college | 1.17 (1.03-1.32) | .01 | 0.70 (0.62-0.79) | <.001 |

| College graduate | 1.34 (1.18-1.52) | <.001 | 0.58 (0.51-0.65) | <.001 |

| Marital status [reference, married] | ||||

| Separated or divorced | 0.86 (0.75-1.00) | .05 | 2.51 (2.23-2.84) | <.001 |

| Widowed | 0.90 (0.82-0.98) | .02 | 2.20 (2.02-2.40) | <.001 |

| Single | 0.77 (0.59-1.00) | .05 | 2.35 (1.87-2.96) | <.001 |

| Wealth quartile [reference, first]b | ||||

| Second | 0.96 (0.87-1.07) | .49 | NA | NA |

| Third | 0.98 (0.88-1.10) | .79 | NA | NA |

| Fourth | 1.17 (1.04-1.32) | .008 | NA | NA |

| Type of supplemental insurance [reference, public] | ||||

| Medicare HMO | 1.80 (1.55-2.08) | <.001 | 1.80 (1.57-2.05) | <.001 |

| Private | 2.38 (2.09-2.71) | <.001 | 1.82 (1.62-2.05) | <.001 |

| None | 2.86 (2.48-3.29) | <.001 | 2.91 (2.57-3.29) | <.001 |

| Disease [reference, none] | ||||

| Cancer | 1.86 (1.55-2.23) | <.001 | 1.47 (1.20-1.79) | <.001 |

| Noncancer conditionc | 1.82 (1.69-1.97) | <.001 | 1.69 (1.57-1.83) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; NA, not applicable.

Values represent estimates from multivariable logistic regression. The regression model is adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, marital status, geographic region, self-assessed health, comorbidities, smoking status, baseline wealth quartile (only for out-of-pocket expenditures), and survey wave. Results for geographic region are not displayed owing to table length. High out-of-pocket expenditures and financial burden refer to participants with out-of-pocket expenditures and financial burden in the highest decile of the distribution of out-of-pocket expenditures and financial burden, respectively.

Wealth was not included as a covariate in logistic regression examining financial burden.

Heart disease, dementia, stroke, type 1 or 2 diabetes, or lung disease.

Adjusted OOP expenditures for HRS participants newly diagnosed with cancer were compared with adjusted OOP expenditures for HRS participants newly diagnosed with common chronic noncancer conditions that contribute to mortality (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Although mean OOP expenditures were similar between disease types for the overall cohort, mean OOP expenditures in participants lacking supplemental insurance were significantly higher for cancer than for other disease types.

All participants newly diagnosed with cancer experienced significantly higher mean annual OOP expenditures following the diagnosis compared with patients with Medicaid coverage (Medicaid, $2116; Veterans Health Administration, $2367; Medicare HMO, $5976; employer-sponsored insurance, $5492; Medigap, $5670; and none, $8115; P < .001 for all) (Table 3). Notably, patients without supplemental insurance experienced the highest mean annual OOP expenditures despite having less income and wealth than patients with all other insurance arrangements except for patients with Medicaid coverage. Similarly, patients without supplemental insurance experienced the greatest financial burden, spending a mean of 23.7% of their total annual household income on OOP expenditures (Table 3). At the 90th percentile, patients lacking supplemental insurance spent 63.1% of their total annual household income on OOP expenditures.

Table 3. Adjusted Level of OOP Expenditures and Financial Burden in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cancer.

| Characteristic | Mean | Median | 90th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|

| OOP expenditures, $a | |||

| Medicaid [reference] | 2116 | 1123 | 7860 |

| Veterans Health Administration | 2367b | 1265b | 8008 |

| Medicare HMO | 5976b | 3052b | 10 761 |

| Employer-sponsored insurance | 5492b | 2663c | 11 437 |

| Medigap | 5670b | 3122b | 11 755 |

| None | 8115b | 3743b | 17 866c |

| Financial burden, %d | |||

| Medicaid [reference] | 8.5 | 2.2 | 24.3 |

| Veterans Health Administration | 5.4e | 3.8 | 27.8 |

| Medicare HMO | 13.2e | 8.0b | 35.7 |

| Employer-sponsored insurance | 12.6e | 6.3c | 37.2 |

| Medigap | 14.1c | 8.0b | 38.8 |

| None | 23.7b | 11.3b | 63.1c |

Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; OOP, out-of-pocket.

Values represent estimates from multivariable generalized linear regression or quantile regression models. Regression models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, educational level, marital status, geographic region, self-assessed health, comorbidities, smoking status, baseline wealth quartile (only for OOP expenditures), and survey wave.

P < .001.

P < .01.

Financial burden = OOP expenditures/total household income.

P < .05.

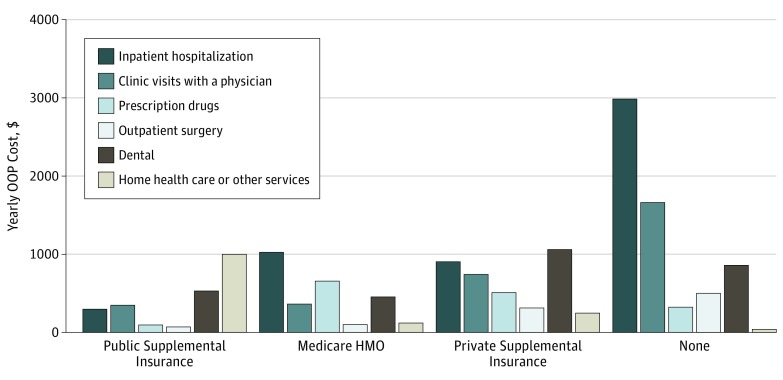

Among patients with cancer, OOP costs from inpatient hospitalization exceeded OOP costs from other service categories. More important, inpatient hospitalization was the primary driver of high OOP expenditures in patients with cancer, representing 42% of total OOP expenditures for patients with OOP costs in the highest decile. The Figure illustrates the contribution of individual OOP cost categories to total OOP costs for patients with cancer, stratified by type of supplemental insurance. Out-of-pocket costs from inpatient hospitalization varied significantly depending on type of supplemental insurance, ranging from 12% of total OOP costs for patients with Medicaid or Veterans Health Administration coverage to 46% for patients lacking supplemental insurance. A total of 380 patients with cancer (27.0%) reported multiple inpatient hospitalizations during the survey interval in which they were diagnosed, but there was no difference in hospitalizations based on insurance classification (65 of 227 patients [28.6%] with public supplemental insurance; 64 of 251 patients [25.5%] with Medicare HMO; 200 of 744 patients [26.9%] with private supplemental insurance; and 51 of 187 patients [27.3%] with no supplemental insurance). Out-of-pocket costs from other service categories also varied based on supplementary insurance type, but the differences were far less pronounced (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Figure. Mean Out-of-Pocket (OOP) Costs for Individual Cost Categories Among Patients Newly Diagnosed With Cancer.

Costs are stratified by type of supplemental insurance. HMO indicates health maintenance organization.

Since medical expenditures associated with cancer care generally follow a U-shaped pattern, with the highest expenditures occurring after initial diagnosis and at the end of life, we also analyzed OOP expenditures at the end of life. Specifically, we measured OOP expenditures incurred in the period between the last survey administration and date of death for 1489 participants who either died of cancer between 2002 and 2012 or were actively receiving cancer treatment at the end of life (eTable 4 in the Supplement). As the median time from the last survey administration to date of death was 1.3 years (interquartile range, 0.8-1.9 years), OOP expenditures were normalized to an annual scale. Findings in decedents with cancer were similar to those newly diagnosed; decedents with cancer who were lacking supplemental insurance experienced the highest level of OOP expenditures at the end of life (eTable 5 in the Supplement), and inpatient hospitalization was the primary contributor to high OOP costs at the end of life (eFigure in the Supplement).

Discussion

A new diagnosis of cancer imposes significant financial strain on community-dwelling, fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries who lack supplemental insurance. Nearly 10% of elderly patients with Medicare alone spent more than 60% of their annual household income on OOP expenditures following a diagnosis of cancer. More important, costs associated with inpatient hospitalization accounted for approximately 40% of total OOP expenditures in patients with cancer who had high OOP costs, including more than 40% of total OOP expenditures in patients with cancer who had Medicare alone; beneficiaries with supplemental coverage were generally protected from high hospital-associated OOP costs. Similar patterns of OOP costs were seen in Medicare beneficiaries who died of cancer.

Inpatient hospitalization represents the largest component of Medicare spending on cancer, both in the initial phase of treatment as well as at the end of life, and is a primary source of regional variation. Although our study was limited by the HRS cost category definitions in its attribution of costs, our results illustrate that inpatient hospitalization may also contribute significantly to high OOP spending in elderly patients with cancer, both at the initial diagnosis and at the end of life, supporting efforts to reduce hospital-associated costs among patients with cancer.

As an example from our institution, recent construction of an oncology-specific urgent care clinic dramatically reduced rates of hospitalization in patients undergoing cancer therapy. Among those treated with radiotherapy, for instance, the mean number of patients who were hospitalized during their course of radiotherapy or within 60 days thereafter decreased from 35 per month to 18 per month following the opening of the oncology-specific urgent care clinic. More important, 35 of 352 hospitalizations (9.9%) during this time resulted in patient liabilities in excess of $2000; among Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental insurance, 4 of 39 hospitalization-associated patient liabilities (10.3%) exceeded $10 000.

Beyond highlighting the need for innovative initiatives for delivery of care, the high level of hospital-associated OOP costs may also demonstrate potential adverse consequences of Medicare’s current design of benefits. For 2016, Medicare’s deductible for Part B services is $166, while its Part A hospital-stay deductible is $1288 per 90-day benefit period. Assigning beneficiaries such a high responsibility of cost sharing for inpatient care may not be an effective use of cost sharing, as hospitalizations are usually not at the discretion of beneficiaries. In the HRS cohort, for example, the frequency of hospitalization did not vary with insurance status. Instead, a unified deductible for all medical services may be a more prudent arrangement and is a feature of several proposals for Medicare reform. More important, these proposals also stipulate an annual maximum on OOP expenditures, another key reform to protect seniors against catastrophic costs. As an example, 73 of 187 patients (39.0%) with cancer in the HRS cohort with Medicare alone experienced OOP costs in excess of the $5500 OOP limit specified in a Congressional Budget Office plan.

Limitations

Although our study has many strengths, important limitations must be acknowledged. Foremost, OOP expenditure data were based on patient self-report, which is subject to recall bias. Survey data are also subject to misclassification and incomplete reporting, although the latter is minimized by the HRS bracketing approach. More important, granular detail on specific services that contributed to OOP costs was limited by the HRS-defined cost categories, and variability in the manner in which costs were assigned by participants may have existed. For example, OOP costs from outpatient radiotherapy services were presumably assigned by participants to the category of clinic visits with a physician, but this categorization cannot be verified. In addition, variability in site of chemotherapy administration likely resulted in its assignment to multiple categories, with inpatient administration of intravenous chemotherapy, for example, likely included in the category of inpatient hospitalization. This possibility may explain the high OOP costs for inpatient admission found in this study. Furthermore, limited information on tumor type and stage prevented further stratification by these key variables. As such, future research to define specific tumor-associated and/or treatment-associated services that contribute to OOP costs should be conducted, perhaps through collaborations with payers that track OOP costs. Moreover, we did not have information on length of stay, including observation status, which can expose beneficiaries to high OOP costs and was becoming increasingly prevalent during the study period. In addition, while our findings in patients who lacked supplementary insurance more broadly reflect the financial effect of cost sharing, Medigap and employer-sponsored insurance plans vary in their generosity of benefits, which we were not able to incorporate into our analysis. Furthermore, our data cannot be extrapolated to the nonelderly and nursing home residents, who were excluded from the study, although our findings may still have implications for younger Americans considering less generous health exchange plans that require significant cost sharing. In addition, our comparisons of the OOP costs between cancer and other chronic conditions assume similar U-shaped cost curves, the applicability of which is unclear for patients with newly diagnosed chronic conditions. Furthermore, the distribution of types of supplemental insurance may not reflect current conditions, particularly with respect to employer-sponsored insurance, as retiree benefits are less generous now than at the beginning of the study period. Finally, our measure for OOP expenditures did not include premiums, an important component of total OOP spending.

Conclusions

Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental insurance incur significant financial burden following a diagnosis of cancer. More important, inpatient hospitalization may represent a key contributor to high OOP costs. Proposals for Medicare reform that restructure the design of benefits for hospital services and incorporate an OOP maximum may help alleviate the risk of financial burden for future beneficiaries, as can interventions that reduce hospitalizations in this population.

eAppendix. Example of HRS Random Entry Bracketing, Components of Household Income and Wealth

eTable 1. Distribution of Supplemental Insurance by Wealth and Income in Patients Newly Diagnosed With Cancer

eTable 2. Adjusted Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Burden in Patients With Cancer, Compared With Patients With Common Noncancer Conditions That Contribute to Mortality in the United States

eTable 3. Mean Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures by Service Category, Stratified by Supplemental Insurance Type

eTable 4. Decedent Characteristics

eTable 5. Adjusted Level Of Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Burden in Decedents With Cancer at End of Life, by Type of Supplemental Insurance

eFigure. Relative Contribution of Individual OOP Cost Categories to Total OOP Costs for Decedents With Cancer at End of Life, Stratified by Whether Participants’ Total OOP Costs Were At or Above the 90th Percentile

References

- 1.Soni A. The five most costly conditions, 1996 and 2006: estimates for the US civilian noninstitutionalized population. https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st248/stat248.pdf. Updated July 2009. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 2.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and statistics. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics. Accessed October 23, 2016.

- 4.The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare chartbook, 2010. http://kff.org/medicare/report/medicare-chartbook-2010/. Updated October 30, 2010. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 5.Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. . Washington state cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1143-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. . The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. Oncologist. 2013;18(4):381-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Toplines: national survey of households affected by cancer. http://kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/toplines-national-survey-of-households-affected-by/. Published November 1, 2006. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 8.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(4):306-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al. . Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(18):2534-2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. . Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119(20):3710-3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298(1):61-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaisaeng N, Harpe SE, Carroll NV. Out-of-pocket costs and oral cancer medication discontinuation in the elderly. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(7):669-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorpe KE, Howard D. Health insurance and spending among cancer patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;W3(suppl):W3-189-W3-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure—out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1484-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. . The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: the COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120(20):3245-3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park). 2013;27(2):80-81, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology . American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(23):3868-3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khera N. Reporting and grading financial toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(29):3337-3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology . American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: a conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment options. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23):2563-2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langa KM, Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, Paisley KL, Hayman JA. Out-of-pocket health-care expenditures among older Americans with cancer. Value Health. 2004;7(2):186-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidoff AJ, Erten M, Shaffer T, et al. . Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(6):1257-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicare Advantage. http://kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/medicare-advantage. Updated May 11, 2016. Accessed July 1, 2016.

- 23.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Fahle S, Marshall SM, Du Q, Skinner JS. Out-of-pocket spending in the last five years of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):304-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juster FT, Suzman R. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. J Hum Resour. 1995;30(suppl):S7-S56. doi: 10.2307/146277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelley AS, Langa KM, Smith AK, et al. . Leveraging the Health and Retirement Study to advance palliative care research. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(5):506-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Health and Retirement Study. Sample sizes and response rates. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/sampleresponse.pdf. Updated Spring 2011. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 27.Kaye HS, Harrington C, LaPlante MP. Long-term care: who gets it, who provides it, who pays, and how much? Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(1):11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading causes of death. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm. Updated October 7, 2016. Accessed October 20, 2016.

- 29.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor. Consumer price index. http://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 30.Chien S, Campbell N, Hayden O, et al. . RAND HRS Data Documentation, Version N. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Center for the Study of Aging; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldman DP, Zissimopoulos J, Lu Y. Medical expenditure measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Forum Health Econ Policy. 2011;14(3):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care: national estimates for the population younger than 65 years, 1996 to 2003. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2712-2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z. National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(20):2821-2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldman DP, Zissimopoulos JM. High out-of-pocket health care spending by the elderly. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(3):194-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Health and Retirement Study: a longitudinal study of health, retirement, and aging sponsored by the National Institute on Aging. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 36.Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, Mariotto A. Economic burden of cancer in the United States: estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(10):2006-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. . Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(9):630-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brooks GA, Li L, Uno H, Hassett MJ, Landon BE, Schrag D. Acute hospital care is the chief driver of regional spending variation in Medicare patients with advanced cancer. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(10):1793-1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brooks GA, Jacobson JO, Schrag D. Clinician perspectives on potentially avoidable hospitalizations in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(1):109-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks GA, Abrams TA, Meyerhardt JA, et al. . Identification of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in patients with GI cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(6):496-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dinan MA, Hirsch BR, Lyman GH. Management of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: measuring quality, cost, and value. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13(1):e1-e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nathan H, Atoria CL, Bach PB, Elkin EB. Hospital volume, complications, and cost of cancer surgery in the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(1):107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes BG, Jain VK, Brown T, et al. . Decreased hospital stay and significant cost savings after routine use of prophylactic gastrostomy for high-risk patients with head and neck cancer receiving chemoradiotherapy at a tertiary cancer institution. Head Neck. 2013;35(3):436-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuntz G, Tozer JM, Snegosky J, Fox J, Neumann K. Michigan oncology medical home demonstration project: first-year results. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(5):294-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sprandio JD. Oncology patient-centered medical home. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(3)(suppl):47s-49s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanghavi D, Samuels K, George M, et al. . Case study: transforming cancer care at a community oncology practice. Healthc (Amst). 2015;3(3):160-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newcomer LN, Gould B, Page RD, Donelan SA, Perkins M. Changing physician incentives for affordable, quality cancer care: results of an episode payment model. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(5):322-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colla CH, Lewis VA, Gottlieb DJ, Fisher ES. Cancer spending and accountable care organizations: evidence from the Physician Group Practice demonstration. Healthc (Amst). 2013;1(3-4):100-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Oncology Care Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Oncology-Care/. Updated October 11, 2016. Accessed October 20, 2016.

- 50.Medicare.gov. Your Medicare costs. https://www.medicare.gov/your-medicare-costs/. Accessed December 1, 2015.

- 51.Congressional Budget Office, Congress of the United States. Reducing the deficit: spending and revenue options. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/120xx/doc12085/03-10-reducingthedeficit.pdf. Published March 2011. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 52.The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. The moment of truth. https://www.fiscalcommission.gov/sites/fiscalcommission.gov/files/documents/TheMomentofTruth12_1_2010.pdf. Updated November 10, 2010. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 53.Moment of Truth Project. Modernizing the Medicare benefit: a closer look at reforming Medicare cost-sharing rules. http://momentoftruthproject.org/publications/modernizing-medicare-benefit-closer-look-reforming-medicare-cost-sharing-rules/. Published June 24, 2013. Accessed July 1, 2015.

- 54.Davis K, Schoen C, Guterman S. Medicare essential: an option to promote better care and curb spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(5):900-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baugh CW, Schuur JD. Observation care—high-value care or a cost-shifting loophole? N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):302-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1251-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Example of HRS Random Entry Bracketing, Components of Household Income and Wealth

eTable 1. Distribution of Supplemental Insurance by Wealth and Income in Patients Newly Diagnosed With Cancer

eTable 2. Adjusted Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Burden in Patients With Cancer, Compared With Patients With Common Noncancer Conditions That Contribute to Mortality in the United States

eTable 3. Mean Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures by Service Category, Stratified by Supplemental Insurance Type

eTable 4. Decedent Characteristics

eTable 5. Adjusted Level Of Out-Of-Pocket Expenditures and Financial Burden in Decedents With Cancer at End of Life, by Type of Supplemental Insurance

eFigure. Relative Contribution of Individual OOP Cost Categories to Total OOP Costs for Decedents With Cancer at End of Life, Stratified by Whether Participants’ Total OOP Costs Were At or Above the 90th Percentile