Abstract

Background

In 2010, New York State began excluding selected patients with cardiac arrest and coma from publicly reported mortality statistics after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). We evaluated the effects of this exclusion on rates of coronary angiography, revascularization, and mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and cardiac arrest.

Methods and Results

Using statewide hospitalization files, we identified discharges for AMI and cardiac arrest 1/2003–12/2013 in New York and several comparator states. A difference-in-differences approach was used to evaluate the likelihood of coronary angiography, revascularization, and in-hospital mortality before and after 2010. A total of 26,379 patients with AMI and cardiac arrest (5,619 in New York) were included. Of these, 17,141 (65%) underwent coronary angiography, 12,183 (46.2%) underwent PCI and 2,832 (10.7%) underwent CABG. Prior to 2010, cardiac arrest patients in New York were less likely to undergo PCI compared with referent states (aRR 0.79, 95% CI 0,73–0.85, p<0.001). This relationship was unchanged after the policy change (aRR 0.82, 95% CI 0.76–0.89, interaction p = 0.359). Adjusted risks of in-hospital mortality between New York and comparator states after 2010 were also similar (aRR 0.94, 95% CI 0.87–1.02, p = 0.152 for post- vs. pre-2010 in New York, aRR 0.88, 95% CI 0.84–0.92, p <0.001 for comparator states; interaction p = 0.103).

Conclusions

Exclusion of selected cardiac arrest cases from public reporting was not associated with changes in rates of PCI or in-hospital mortality in New York. Rates of revascularization in New York for cardiac arrest patients were lower throughout.

Keywords: Public Reporting, PCI, New York, acute myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest

Public reporting of risk-adjusted mortality statistics after cardiovascular procedures is increasingly used as an outcome measure to compare the quality of physicians and hospitals. New York State was the first to publicly report in-hospital mortality after cardiac surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), with other states subsequently implementing similar programs.1 Health care payers have embraced these outcomes and considered using them to determine both individual and hospital level reimbursement to provide additional incentives to improve the overall quality of care.2–3 A number of changes have been made in the collection and analysis of clinical outcomes since the institution of public reporting two decades ago, possibly with an impact on patient care.4–5

Public reporting of outcomes may lead to physician risk avoidance and inappropriate exclusion of patients from the potential life-saving benefits of revascularization because of perceived high-risk.6–8 This is of particular note in the setting of resuscitated out-of-hospital cardiac arrest where the majority of hospitalized patients do not survive to discharge, dying of neurologic causes or multi-organ failure rather than complications of their cardiovascular care.9 As a result, the American Heart Association in 2013 published guidelines recommending against routine public reporting of PCI outcomes in resuscitated cardiac arrest.9 Despite this report, exclusion of cardiac arrest from publicly reported mortality statistics has not been uniformly adopted by all states.10–12

As a result of increasing concern about the impact of physician risk aversion, the New York State Department of Public Health has excluded very selected patients with cardiac arrest and hypoxic brain injury who undergo PCI from public reporting of in-hospital mortality since January 1, 2010.12 In contrast to the broad exclusion of patients with cardiogenic shock,4–5 the cardiac arrest exclusion was narrowly defined, requiring documentation of anoxic encephalopathy by a consulting neurologist or intensivist as well as a chart documentation of consultant agreement with the decision to withdraw care or family requests for care to be withheld12. With this in mind, we assessed the change in rates of coronary angiography, PCI, and in-hospital mortality, first, among all MI patients with cardiac arrest, and second, among those with arrest complicated by hypoxic brain injury before and after this policy change in 2010 in New York, compared to several other states during the same time period.

METHODS

Study Population

The State Inpatient Databases consist of a group of comprehensive, all-payer, de-identified, inpatient discharge records from hospitals within a given state, published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. In this analysis, we utilized the state inpatient databases for New York, Massachusetts, Michigan, and New Jersey from January 1, 2003, until December 31, 2013, and in California from January 1, 2003, until December 31, 2011 (due to availability). New York State was considered to be the primary analytic cohort with the other states included as comparators to control for secular trends. Michigan, New Jersey, and California do not publicly report mortality after PCI while Massachusetts does publicly report mortality and includes patients with cardiac arrest.10 Massachusetts was included as a comparator state as it lacks a cardiac arrest exclusion,10 and thus was not expected to significantly affect conclusions regarding the specific exclusion policy evaluated. However, as Massachusetts, in 2009, began permitting exclusion of selected PCI cases from public reporting for “exceptional risk” as determined through an individual adjudication protocol,10 a sensitivity analysis was also performed removing Massachusetts from the analysis to evaluate if conclusions were altered.

Patients were included in the analysis if they were admitted with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of AMI and cardiac arrest in either order using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. We used discharge codes for AMI, defined by non-ST-segment elevation MI (410.71 and 410.91) and ST-segment elevation MI (410.11–410.61 and 410.81) that have been previously validated in other data sets.13 Cardiac arrest was identified using code 427.5. Patients admitted to hospitals without the capacity to perform PCI or low-volume PCI centers (<10 PCI/year) were excluded. Additionally, patients whose disposition was to a short-term facility were excluded to avoid double counting of hospitalizations for the same presentation, but patients transferred into a hospital were included in the analysis. As all patient level data were de-identified, this study was considered to be exempt from institutional review board approval and research was conducted in accordance with the data use agreement as specified by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, a product of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Measurements

Demographic characteristics and pertinent covariates, including patient age, sex, race, and 29 comorbid conditions as defined by the risk adjustment model developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality14 were abstracted from the data set (eTable 1 in Supplemental Appendix). Validated codes for coma (780.01) and anoxic brain injury (348.1) were used to define the subgroup of cardiac arrest patients with coma or anoxic brain injury.15 Procedural codes for PCI (ICD-9-CM codes 00.66, 17.55, 36.01, 36.02, 36.05, 36.06, and 36.07) and coronary angiography (ICD-9-CM codes 37.21, 37.22, 37.23, 88.52, 88.53, 88.54, 88.55, 88.56, and 88.57) were used to identify those undergoing revascularization.16 The primary outcomes of the study were the receipt of coronary angiography or PCI and in-hospital all-cause mortality.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means plus standard deviations and dichotomous categorical data are presented as percentages. The data set was stratified into two cohorts reflecting the period prior to the New York State policy change (2003–2010) and the period after this change (2010–2013). Patient characteristics were compared for the periods before and after the policy change for the total sample and in New York and comparator states separately using the t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. To evaluate the association of the policy change with rates of coronary angiography, PCI, and in-hospital death for the subgroup of patients with AMI and cardiac arrest, we used a difference-in-differences approach, utilizing a Modified Poisson regression model to evaluate the relative risk of outcomes between New York and comparator states in both the pre- and post-policy periods (before and after 2010), and evaluating a state x time period interaction term (eFigure 1). Hospital site was included as a random effect in the model to adjust for the clustering of outcomes by hospital. Additionally, the regression model incorporated covariates for age, gender, ST-segment elevation MI presentation and the 29 comorbid medical conditions previously mentioned. Additionally, to evaluate for yearly temporal trends in treatment and mortality before and after the policy, we constructed similar Modified Poisson multivariate regression models with calendar year as a categorical variable, using each year as a category and 2003 as the reference year.

Sensitivity analyses were performed through repetition of the primary analysis after serial removal of individual comparator states to ensure that the results were not driven by one state. To evaluate for changes in coding that could confound the observed results, we separately evaluated the overall rates of cardiac arrest (as a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis) during the study time period for individuals with AMI (as a primary or secondary diagnosis) as well as the subgroup of these individuals with coma or anoxic brain injury. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software, SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.), utilizing two-sided p-value of <0.05 to denote significance.

RESULTS

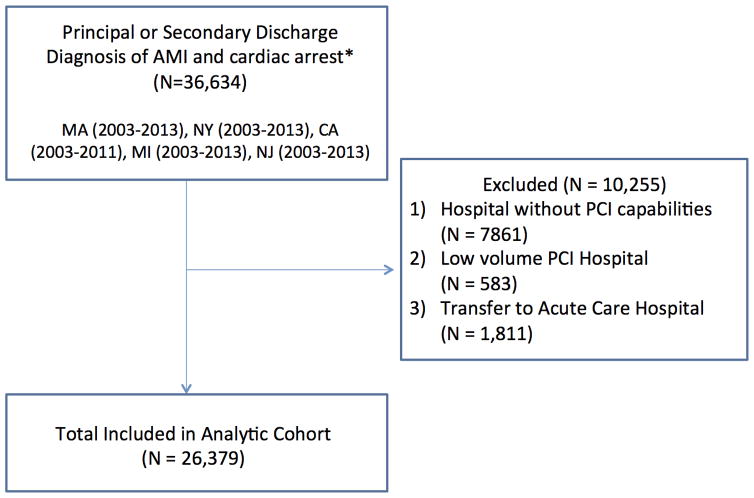

A total of 36,634 patients with AMI and cardiac arrest between 2003 and 2013 were identified, of which, 26,379 (72%) were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Of these, 5,619 (21.3%) were in New York. The mean age (SD) of participants was 68.0 (13.8) and 9,668 were female (36.7%). There were 17,126 (64.9%) patients in the pre-policy period (2003–2010) and 9,253 (35.1%) in the post-policy period (2010–2013). Differences in patient level covariates are listed in Table 1. In both New York and elsewhere, rates of coronary angiography and PCI were higher after 2010, while rates of CABG declined. (Table 2). Unadjusted rates of coronary angiography or any revascularization (PCI or CABG) were lower in New York compared to comparator states both before and after 2010. Unadjusted in-hospital mortality remained >40% but declined in both New York and comparator states over the study time period (New York; 42.9% post-2010 and 46.8% pre-2010; p = 0.003; Comparator states; 45.6% post-2010 and 53.2% pre-2010; p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Study Design and Overview. *Individuals were included in the analysis with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of AMI and cardiac arrest in either order. Abbreviations: AMI = Acute Myocardial Infarction. CA = California. MA = Massachusetts. MI = Michigan. NJ = New Jersey. NY = New York. PCI = Percutaneous Coronary Intervention.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients presenting with AMI and cardiac arrest by study period*

| Total (N = 26 379) | 2003–2009 (N = 17 126) | 2010–2013 (N = 9 253) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y† | 68.0 ± 13.8 | 68.3 ± 13.8 | 67.4 ± 13.8 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 9668 (36.7) | 6435 (37.6) | 3233 (34.9) | < 0.001 |

| ST-segment MI | 13188 (50.0) | 8575 (50.1) | 4613 (49.9) | 0.737 |

| Coma | 1093 (4.1) | 629 (3.7) | 464 (5.0) | < 0.001 |

| Anoxic brain injury | 5697 (21.6) | 3630 (21.2) | 2067 (22.3) | 0.031 |

| Hospital state | < 0.001 | |||

| California | 8213 (31.1) | 6288 (36.7) | 1925 (20.8) | |

| Massachusetts | 2846 (10.8) | 1825 (10.7) | 1021 (11.0) | |

| Michigan | 6327 (24.0) | 3902 (22.8) | 2425 (26.2) | |

| New Jersey | 3374 (12.8) | 1931 (11.3) | 1443 (15.6) | |

| New York | 5619 (21.3) | 3180 (18.6) | 2439 (26.4) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 689 (2.6) | 444 2.6) | 245 (2.6) | 0.788 |

| Valvular disease | 182 (0.7) | 126 (0.7) | 56 (0.6) | 0.221 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 76 (0.3) | 50 (0.3) | 26 (0.3) | 0.874 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 2827 (10.7) | 1695 (9.9) | 1132 (12.2) | < 0.001 |

| Paralysis | 522 (2.0) | 334 (2.0) | 188 (2.0) | 0.650 |

| Other neurological disorders | 2510 (9.5) | 1553 (9.1) | 957 (10.3) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 4898 (18.6) | 3127 (18.3) | 1771 (19.1) | 0.079 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 6529 (24.8) | 4066 (23.7) | 2463 (26.6) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 1534 (5.8) | 965 (5.6) | 569 (6.1) | 0.088 |

| Renal failure | 5438 (20.6) | 3528 (20.6) | 1910 (20.6) | 0.936 |

| Liver disease | 347 (1.3) | 199 (1.2) | 148 (1.6) | 0.002 |

| Obesity | 2348 (8.9) | 1250 (7.3) | 1098 (11.9) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension, complicated and uncomplicated | 14735 (55.9) | 9070 (53.0) | 5665 (61.2) | < 0.001 |

All data are presented as number (percentage) of subjects unless otherwise indicated.

Age on admission.

Abbreviation: MI = myocardial infarction. SD = Standard Deviation. y = years. Data are presented as number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise specified.

Table 2.

Number (Percentage) of Treatment and Outcomes by State Overall

| New York | Comparator States | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2010 (N = 3180) | 2010–2013 (N = 2439) | P-value | 2003–2010 (N = 13 946) | 2010–2013 (N = 6814) | P-value | |

| Coronary angiography | 1912 (60.1) | 1529 (62.7) | 0.050 | 8992 (64.5) | 4708 (69.1) | < 0.001 |

| PCI | 1141 (35.9) | 1082 (44.4) | < 0.001 | 6389 (45.8) | 3571 (52.4) | < 0.001 |

| CABG | 405 (12.7) | 227 (9.3) | < 0.001 | 1609 (11.5) | 591 (8.7) | < 0.001 |

| Shock | 803 (25.3) | 811 (33.3) | < 0.001 | 3415 (24.5) | 2073 (30.4) | < 0.001 |

| Coma | 108 (3.4) | 123 (5.0) | 0.002 | 521 (3.7) | 341 (5.0) | < 0.001 |

| Anoxic brain injury | 644 (20.3) | 561 (23.0) | 0.012 | 2986 (21.4) | 1506 (22.1) | 0.256 |

| Any Revascularization | 1504 (47.3) | 1282 (52.6) | < 0.001 | 7688 (55.1) | 4056 (59.5) | < 0.001 |

| Catheterization or Revascularization | 2027 (63.7) | 1612 (66.1) | 0.067 | 9442 (67.7) | 4906 (72.0) | < 0.001 |

| In-Hospital Mortality | 1489 (46.8) | 1047 (42.9) | 0.003 | 7406 (53.2) | 3107 (45.6) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting. Any revascularization is defined by PCI or CABG.

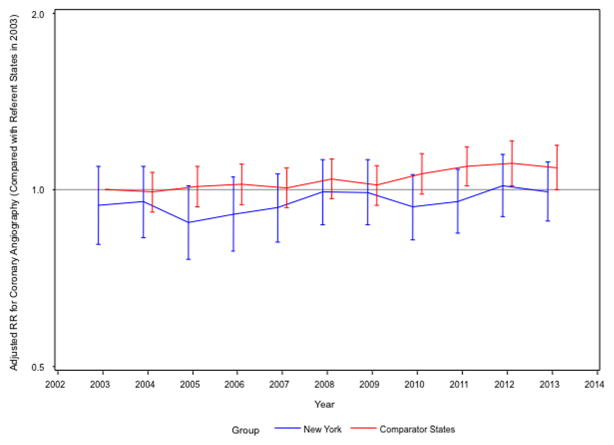

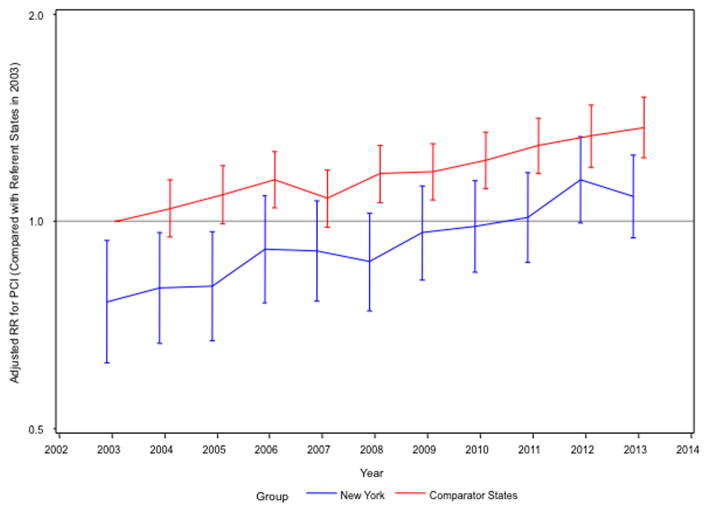

After multivariable adjustment for patient demographics and comorbid risk factors, adjusted rates of coronary angiography for myocardial infarction patients with cardiac arrest remained lower in New York than comparator states, with no change after the policy implementation (adjusted relative risk [aRR] 0.93; 95% CI 0.88–0.99; p = 0.035 pre-2010 versus aRR 0.90; 95% CI 0.84–0.96; p = 0.003 post-2010; interaction p 0.323) (Figure 2). Similarly, the multivariable adjusted rates of PCI in New York remained lower than in comparator states (aRR 0.79; 95% CI 0.73–0.85; p <0.001 pre-2010 versus aRR 0.82; 95% CI 0.76–0.89; p <0.001 post; interaction p = 0.359). Similar increases in PCI utilization for cardiac arrest patients were observed in both New York and comparator states (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Adjusted relative risk (aRR) of patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest who undergo coronary angiography annually in NY and comparator states (reference comparator states in 2003). Error bars indicate 95% CI.

Figure 3.

Adjusted relative risk (aRR) of patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) annually in NY and comparator states (reference comparator states in 2003). Error bars indicate 95% CI.

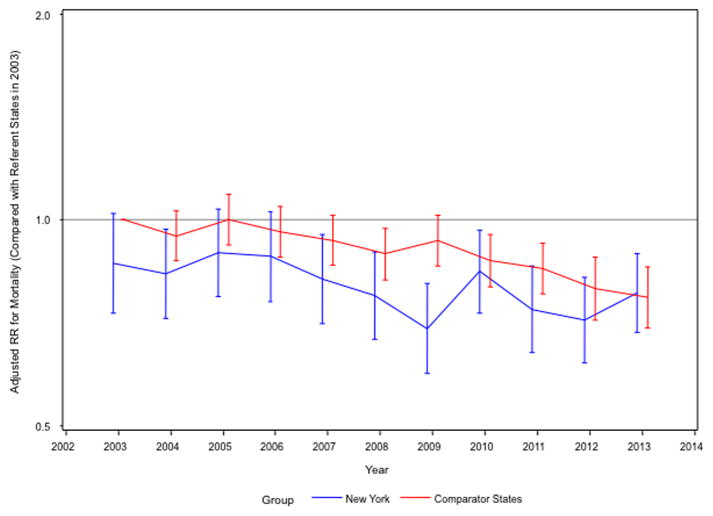

Adjusted in-hospital mortality did not change significantly after implementation of the policy in New York while declining in comparator states, although the interaction term was not significant (New York: post-2010 vs. pre-2010 aRR 0.94; 95% CI 0.87–1.02; p = 0.152; comparator states: aRR 0.88; 95% CI 0.84–0.92; p < 0.001, interaction p = 0.103) (Figure 4). Adjusted in-hospital mortality for AMI patients with cardiac arrest was lower in New York throughout the study period (Pre 2010: New York vs. comparator states aRR 0.86 95% CI 0.80–0.92; p <0.001; Post-2010: aRR 0.92 95% CI 0.85–1.00; p = 0.52; p interaction 0.103). Overall, 103 patients (0.07%) in years 2010–2012 with cardiac arrest after AMI and anoxic brain injury who expired were excluded from the publicly reported risk-adjusted mortality.12

Figure 4.

Adjusted relative risk (aRR) of in-hospital mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest annually in NY and comparator states (reference comparator states in 2003). Error bars indicate 95% CI.

A sensitivity analysis was performed with sequential removal of each state from the analysis, which did not demonstrate any significant changes in the results (eFigures 2–4 in Supplemental Appendix). Additionally, to assess whether changes in coding that could confound the results, we evaluated overall rates of coding for cardiac arrest over time in the cohort of patients with AMI. This analysis demonstrated numerically lower overall cardiac arrest rates in New York versus comparator states post-AMI and lower rates of cardiac arrest with coma or brain injury. (eFigures 5–6 in Supplemental Appendix).

In the subgroup with cardiac arrest post-AMI and coma or anoxic brain injury, no significant effect of the policy exclusion on outcomes was observed (Table 3). Adjusted coronary angiography rates remained lower in New York compared with comparator states (aRR 0.79; 95% CI 0.68–0.91; p = 0.001 for New York vs. comparator states pre-2010 and aRR 0.74; 95% CI 0.64–0.86; p < 0.001 for New York vs. comparator states post-2010; interaction p = 0.526). Similarly, adjusted rates of PCI were lower in New York than comparator states (aRR 0.58; 95% CI 0.48–0.71; p < 0.001 for New York vs. comparator states pre-2010 and aRR 0.66; 95% CI 0.55–0,79; p < 0.001 for New York vs. comparator states post-2010; interaction p = 0.320). Lastly, adjusted in-hospital mortality rates did not differ between New York and comparator states with respect to timing of the policy implementation (aRR 0.94; 95% CI 0.84–1.04; p = 0.218 for New York vs. comparator states pre-2010 and aRR 1.01; 95% CI 0.9–1.14; p = 0.91 for New York vs. comparator states post-2010; interaction p = 0.370).

Table 3.

Number (Percentage) of Treatment and Outcomes by State in the Subgroup with Coma or Anoxic Brain Injury

| New York | Comparator States | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003–2010 (N = 668) | 2010–2013 (N = 608) | P-value | 2003–2010 (N = 3133) | 2010–2013 (N = 1636) | P-value | |

| Coronary angiography | 236 (35.3) | 256 (42.1) | 0.013 | 1429 (45.6) | 932 (57.0) | < 0.001 |

| PCI | 129 (19.3) | 178 (29.3) | < 0.001 | 1046 (33.4) | 694 (42.4) | < 0.001 |

| CABG | 37 (5.5) | 25 (4.1) | 0.236 | 122 (3.9) | 70 (4.3) | 0.521 |

| Shock | 183 (27.4) | 228 (37.5) | < 0.001 | 793 (25.3) | 536 (32.8) | < 0.001 |

| Coma | 108 (16.2) | 123 (20.2) | 0.059 | 521 (16.6) | 341 (20.8) | < 0.001 |

| Anoxic brain injury | 644 (96.4) | 561 (92.3) | 0.001 | 2986 (95.3) | 1506 (92.1) | < 0.001 |

| Any Revascularization | 202 (33.2) | 163 (24.4) | < 0.001 | 1150 (36.7) | 756 (46.2) | < 0.001 |

| Catheterization or Revascularization | 267 (43.9) | 249 (37.3) | 0.015 | 1491 (47.6) | 969 (59.2) | < 0.001 |

| In-Hospital Mortality | 384 (63.2) | 440 (65.9) | 0.312 | 2176 (69.5) | 1010 (61.7) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting. Any revascularization is defined by PCI or CABG.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that the policy to exclude cardiac arrest patients with anoxic brain injury in New York did not significantly change rates of coronary angiography, PCI, or in-hospital mortality for those individuals with cardiac arrest after AMI. Although rates of coronary angiography, PCI and any revascularization for cardiac arrest patients increased in all states over time, they remained lower in New York compared with California, Massachusetts, Michigan and New Jersey throughout the study period. These differences in invasive management were strongest among patients with cardiac arrest with concomitant coma or brain death, despite the policy change targeted at addressing this population.

A number of prior studies of have shown results consistent with avoidance of high risk patients by physicians in public reporting environments.4–8 In order to mitigate these effects, both Massachusetts and New York have changed their public reporting methodology, in both cases to remove potential disincentives to treat high risk patients such as those with cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest. In 2006, New York began excluding patients with cardiogenic shock from publicly reported mortality metrics.12 The 2006 policy in New York resulted in increased rates of PCI and decreased in-hospital mortality in New York despite persistently lower overall rates of PCI relative to other states.4–5 However, the 2010 change in policy around the exclusion of selected cardiac arrest patients had previously not been evaluated.

The results of this study are consistent with the idea that such a policy was not sufficient to mitigate physician reluctance to perform procedures in high-risk cases in a public reporting environment. This reluctance may be due to the limited scope of the policy change or continued skepticism among PCI operators regarding the adequacy of the publically reported risk-adjustment methods used.

The New York State policy exclusion for patients with cardiac arrest after AMI and anoxic brain injury was narrowly defined and as such, only 103 patients in years 2010–2013 with cardiac arrest after AMI and anoxic brain injury who expired were excluded from the publicly reported risk-adjusted mortality, representing 0.07% of all PCI cases during 2010–2012 years.12 While the New York policy change may have increased the number of individuals with cardiac arrest receiving PCI meeting the narrow exclusion criteria, this information is not captured in the administrative data. However, our study demonstrates that this narrow exclusion was insufficient to alter rates of PCI for the overall population with cardiac arrest. It is possible, therefore, that the narrowly defined exclusion criteria would apply to a very small number of patients and would be insufficient to counter physician concerns regarding inadequate risk adjustment and the perceived risk of public reporting and thereby would be unsuccessful in influencing PCI operator behavior. Guidelines from the American Heart Association published in 2013 currently recommend the broader exclusion of all cardiac arrests from public reporting.9 Moreover, while there is robust evidence from randomized trials supporting the role of emergent PCI in cardiogenic shock,17 there are currently no trials supporting use of emergent PCI in cardiac arrest, with resultant equipoise in clinical management of these patients. Two studies, the Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial of Early Coronary Angiography Versus No Early Coronary Angiography for Post-Cardiac Arrest Patients Without ECG ST Segment Elevation (PEARL) trial (NCT02387398) and the Direct or Subacute Coronary Angiography for Out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest (DISCO) trial (NCT02309151) are currently enrolling.

In-hospital mortality rates among cardiac arrest patients declined over time, but remained greater than 40% throughout the study period in both New York and elsewhere. Notably, adjusted in-hospital mortality rates were similar or lower in New York than comparator states, despite the lower revascularization rates. This finding may reflect other difference in quality of care unrelated to coronary revascularization, as well as accurate identification of cardiac arrest patients for whom PCI may be medically futile in New York, especially given the high reported mortality in cardiac arrest patients. Whether increasing the rates of coronary revascularization in New York would change overall mortality results significantly remains unknown.

There are a number of limitations to this study that are worth noting. First, the data are abstracted from claims data and suffer from limitations including potential errors in coding, inability to capture all relevant comorbidities, and limited data on pre-hospital and post-resuscitative measures that may be potential confounders (e.g. quality of CPR, response times, temperature management, etc.). Additionally, the ICD-9 code for cardiac arrest is not specific for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and may include inpatient cardiac arrests as well for whom physician decision making may differ. The study is observational in nature, and although we conducted an analysis controlling for secular trends through a difference-in-difference approach, causal relationships between the New York policy change and subsequent outcomes cannot be assumed. Next, it is possible that certain regional trends may explain differences in patterns observed. We purposefully chose a geographically diverse control population to help mitigate this concern, and the results from the sensitivity analysis sequentially removing each state were consistent with overall findings. Finally, we were limited in the data set to study in-hospital outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Patients presenting the myocardial infarction complicated by cardiac arrest in New York State have lower rates of angiography and PCI compared with other states. These trends continued after the implementation of a policy to excluded selected cardiac arrest patients from public reporting in New York. Mortality after cardiac arrest was high throughout the study period.

Supplementary Material

What is Known

Public reporting of outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is used to compare quality of physicians and hospitals.

Public reporting of outcomes may lead to inappropriate exclusion of patients from PCI due to perceived high risk.

Due to concern about physician risk avoidance, in 2010, the New York State Department of Public Health excluded selected patients with cardiac arrest and hypoxic brain injury who undergo PCI from public reporting, but the impact of this policy is unknown.

What the Study Adds

The New York State exclusion of selected cardiac arrest patients from public reporting in 2010 did not impact rates of PCI or in-hospital mortality.

Rates of coronary angiography or any revascularization remained lower in New York compared with referent states throughout the study period.

Mortality declined in all states over the study period but remained >40%.

Results were similar when limited to those patients with coma or anoxic brain injury and cardiac arrest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Richard A. and Susan F. Smith for their generous contribution to cardiovascular outcomes research.

Sources of Funding: Funding for this project was provided by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center’s T32 grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (Dr. Strom) and the Richard and Susan Smith Center for Outcomes Research (Dr. Yeh)

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.McCabe JM, Resnic FS. Strenghtening public reporting and maintaining access to care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:793–796. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drozda JP, Jr, Hagan EP, Mirro MJ, Peterson ED, Wright JS American College of Cardiology Foundation Writing Committee. ACCF 2008 health policy statement on principles for public reporting of physician performance data: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Writing Committee to develop principles for public reporting of physician performance data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1993–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Califf RM, Peterson ED. Public reporting of quality measures: what are we trying to accomplish? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:831–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCabe JM, Waldo SW, Kennedy KF, Yeh RW. Treatment and Outcomes of Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Shock After Policy Changes in New York State Public Reporting. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:648–54. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangalore S, Guo Y, Blecker S, Gupta N, Feit F, Hochman JS. Rates of Invasive Management of Cardiogenic Shock in New York Before and After Exclusion From Public Reporting. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:640–7. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldo SW, McCabe JM, O’Brien C, Kennedy KF, Joynt KE, Yeh RW. Association between public reporting of outcomes with procedural management and mortality for patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1119–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnic FS, Welt FGB. The public health hazards of risk avoidance associated with public reporting of risk-adjusted outcomes in coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner RM, Asch DA. The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information. JAMA. 2005;293:1239–1244. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peberdy MA, Donnino MW, Callaway CW, Dimaio JM, Geocadin RG, Ghaemmaghami CA, Jacobs AK, Kern KB, Levy JH, Link MS, Menon V, Ornato JP, Pinto DS, Sugarman J, Yannopoulos D, Ferguson TB, Jr American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee. Council on Cardiopulmonary Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Impact of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Performance Reporting on Cardiac Resuscitation Centers: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:762–733. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182a15cd2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Massachusettts Data Analysis Center. Adult Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts: Fiscal Year 2013 Report (October 1, 2012 through September 30, 2013) Hospital Risk-Standardized In-Hospital Mortality Rates. [Accessed July 29, 2016];2015 Oct; Available at: http://www.massdac.org/wp-content/uploads/PCI-FY2013.pdf.

- 11.Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program. [Accessed July 29, 2016];Participating Hospitals and Publicly Released COAP Data: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) Outcomes. 2014 Jun; Available at: http://www.coap.org/downloads/COAP-2013-dashboard-summary.pdf.

- 12.New York State Department of Health. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) in New York State 2010–2012. New York: New York State Dept of Health; Oct, 2015. pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massachusetts Data Analysis Center (Mass-DAC) Monitoring Cardiac Care in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts: A Preliminary Report. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Data Analysis Center; 2004. pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 14.HCUP Elixhauser Comorbidity Software. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, Maryland: Jun, 2016. [Accessed July 29, 2016]. Available: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joynt KE, Blumenthal DM, Orav EJ, Resnic FS, Jha AK. Association of public reporting for percutaneous coronary intervention with utilization and outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2012;308:1460–1468. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.12922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carnahan RM, Herman R. [Accessed July 29, 2016];Mini-Sentinel Systematic Evaluation of Health Outcome of Interest Definitions for Studies Using Administrative Data: Transfusion-Associated Sepsis or Septicemia Report. 2011 Jun 14; Available at: http://www.mini-sentinel.org/work_products/HealthOutcomes/Mini-Sentinel-HOI-Evidence-Review-Transfusion-Related-Sepsis-Report.pdf.

- 17.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Sanborn TA, White HD, Talley JD, Buller CE, Jacobs AK, Slater JN, Col J, McKinlay SM, LeJemtel TH. Early Revascularization in Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:626–634. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.