Abstract

Background

Emergency department (ED)-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone with continuation in primary care was found to increase engagement in addiction treatment and reduce illicit opioid use at 30 days compared to referral only or a brief intervention with referral.

Objective

To evaluate the long-term outcomes at 2, 6 and 12 months following ED interventions.

Design

Evaluation of treatment engagement, drug use, and HIV risk among a cohort of patients from a randomized trial who completed at least one long-term follow-up assessment.

Participants

A total of 290/329 patients (88% of the randomized sample) were included. The followed cohort did not differ significantly from the randomized sample.

Interventions

ED-initiated buprenorphine with 10-week continuation in primary care, referral, or brief intervention were provided in the ED at study entry.

Main Measures

Self-reported engagement in formal addiction treatment, days of illicit opioid use, and HIV risk (2, 6, 12 months); urine toxicology (2, 6 months).

Key Results

A greater number of patients in the buprenorphine group were engaged in addiction treatment at 2 months [68/92 (74%), 95% CI 65–83] compared with referral [42/79 (53%), 95% CI 42–64] and brief intervention [39/83 (47%), 95% CI 37–58; p < 0.001]. The differences were not significant at 6 months [51/92 (55%), 95% CI 45–65; 46/70 (66%) 95% CI 54–76; 43/76 (57%) 95% CI 45–67; p = 0.37] or 12 months [42/86 (49%) 95% CI 39–59; 37/73 (51%) 95% CI 39–62; 49/78 (63%) 95% CI 52–73; p = 0.16]. At 2 months, the buprenorphine group reported fewer days of illicit opioid use [1.1 (95% CI 0.6–1.6)] versus referral [1.8 (95% CI 1.2–2.3)] and brief intervention [2.0 (95% CI 1.5–2.6), p = 0.04]. No significant differences in illicit opioid use were observed at 6 or 12 months. There were no significant differences in HIV risk or rates of opioid-negative urine results at any time.

Conclusions

ED-initiated buprenorphine was associated with increased engagement in addiction treatment and reduced illicit opioid use during the 2-month interval when buprenorphine was continued in primary care. Outcomes at 6 and 12 months were comparable across all groups.

KEY WORDS: opioid use disorder, substance use disorder, emergency medicine, primary care

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of the non-medical use of prescription opioids, the use of heroin, and opioid overdose mortality have escalated to epidemic proportions, prompting urgent calls for expanded access to treatment for opioid use disorder (previously referred to as opioid dependence).1 – 3 Opioid agonist treatment, including methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone (hereafter referred to as buprenorphine), is the most effective treatment and is associated with improved health and social outcomes and disease prevention.4 , 5 Patients with opioid use disorder are at increased risk for adverse health consequences, and often use the emergency department (ED) to treat these problems. Thus, the ED offers an opportunity to screen for opioid use disorder, provide interventions and facilitate referral to ongoing treatment.

We previously published 30-day outcomes from a clinical trial of patients who met criteria for opioid dependence (currently classified as moderate/severe opioid use disorder, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [DSM-5]) that were randomized to one of three interventions: referral, brief intervention or ED-initiated buprenorphine followed by 10 weeks of continued buprenorphine treatment in a primary care setting.6 Patients receiving ED-initiated buprenorphine with continuation in primary care were more likely to be engaged in formal addiction treatment at 30 days than were those in the brief intervention or referral groups (78% vs. 45% vs. 37%, respectively, p < 0.001). This finding provides a new paradigm for ED-initiated treatment of patients with moderate/severe opioid use disorder.

ED-based interventions typically focus on the acute stabilization and treatment of medical conditions, with the goal of ED care to engage patients in ongoing treatment. Similar to ED presentations of exacerbations of other chronic diseases such as diabetes and asthma, our results demonstrate that ED providers can initiate buprenorphine treatment for moderate/severe opioid use disorders and facilitate linkage to community-based providers including primary care and other office-based physicians who prescribe buprenorphine. However, it is unknown how long the benefits of ED-initiated buprenorphine with continuation in primary care will last. We now present the results of a cohort from our original sample and outcomes observed at 2 months (during primary care-based buprenorphine treatment provided as a part of the randomized clinical trial) and at 6 and 12 months.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

We report on a cohort of patients that completed at least one follow-up assessment at 2, 6 or 12 months, who were recruited into a randomized trial conducted at a large urban teaching hospital and its affiliated primary care center from April 7, 2009, to June 25, 2013. The methods have been reported in detail previously.6

ED patients 18 years of age and older were screened using a 20-item health questionnaire containing embedded questions related to prescription opioid and heroin use. Patients were excluded if they were non-English-speaking, critically ill, unable to communicate due to dementia or psychosis, suicidal, or in police custody. Patients reporting non-medical use of prescription opioids or any heroin use in the past 30 days were excluded if they were enrolled in formal addiction treatment, required hospitalization or were receiving opioid medication for pain. Patients with an opioid-positive urine test (opiates or oxycodone) and a Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview score ≥ 3 for opioid dependence using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria7 were eligible for inclusion. Informed consent was obtained by research associates (RAs). The study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Yale School of Medicine.

Treatment Conditions

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to one of three study groups. The use of a computerized stratified randomization procedure8 by an investigator (MCC) ensured that the groups were balanced with regard to sex, cocaine use in the last 30 days, and primarily prescription opioid or heroin use.

Referral

Referral patients received a handout providing names, locations and phone numbers of addiction treatment services consistent with their insurance plan in the area and telephone access. These addiction services included a range of treatments of varying intensity and duration, including opioid treatment programs, inpatient or residential treatment, and outpatient services including intensive outpatient programs and office-based providers of buprenorphine or other forms of treatment. The RA avoided motivating statements. Patients in the referral and brief intervention groups described below received management of withdrawal symptoms at the discretion of the ED physician.

Brief Intervention

A 10–15-minute manual-driven audiotaped Brief Negotiation Interview (BNI) was performed by an RA.9 The BNI, described previously,10 was modified for opioid dependence and contained four components: Raise the Subject, Provide Feedback, Enhance Motivation, and Negotiate and Advise. The RA discussed a variety of treatment options based on patient insurance, residence and preferences, and directly linked the patient with the referral. This included reviewing the patient’s eligibility for services, obtaining insurance clearance and arranging transportation.

Buprenorphine

Patients in the buprenorphine group received a BNI and ED-initiated treatment with buprenorphine if they exhibited moderate to severe opioid withdrawal.11 Sufficient take-home daily doses were provided to ensure they had adequate medication until a scheduled appointment in the hospital’s primary care center, within 72 hours. Buprenorphine doses were 8 mg on day 1 and 16 mg on days 2 and 3. In the 65 (57%) patients not manifesting opioid withdrawal in the ED, buprenorphine was provided for unobserved (e.g., home) induction, with a detailed self-medication guide.12

Primary care-based buprenorphine treatment was continued for 10 weeks by physicians and nurses using established procedures, with visits ranging from weekly to twice monthly based on clinical stability.13 , 14 Clinicians and study investigators providing buprenorphine treatment were blinded to research assessments. Receipt of buprenorphine treatment was not contingent upon abstinence from illicit drug use. After completing 10 weeks of primary care-based buprenorphine treatment within this study, all patients were offered referral for transitioning to an opioid agonist treatment program tailored to their stability, insurance and preference in a non-study community-based treatment setting. As an alternative, patients who requested it were provided detoxification over a 2-week period and a referral for ongoing care (e.g., naltrexone and counseling).

Long-Term Follow-Up Assessments

The long-term follow-up assessments at 2, 6 and 12 months included the Treatment Services Review,15 , 16 timeline follow-back assessment of illicit opioid use in the preceding 7 days,17 and an 11-item validated scale for and HIV risk-taking related to drug use and sexual behavior.18 Assessments at 2 and 6 months were completed primarily face-to-face (88% and 82% face-to-face and 12% and 18% telephone, respectively) by trained, supervised and scripted RAs in a clinical setting separate from primary care or other treatment sites. The 12-month assessment was completed primarily by phone (84% telephone, 16% face-to-face) by the same research personnel. The RAs were blinded to group assignment and not involved in any aspect of the patient’s care. Patients who completed face-to-face interviews at 2 and 6 months also provided a urine sample for drug toxicology testing. Urine samples were tested for opioid metabolites (morphine, oxycodone) using a rapid qualitative immunoassay. Patients did not receive feedback regarding the results of their urine tests and were informed that all research assessment data were confidential and not available to the treatment providers. To minimize bias, surveillance for and determination of all outcome data were carried out in a uniform manner across all three treatment conditions. The follow-up assessment sessions lasted between 20 and 30 min on average, and patients received $50.00 gift cards for participation in each of the follow-up assessments.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for the current study, engagement in formal addiction treatment at the time of the 2-, 6- and 12-month assessments, was by self-report using the Treatment Services Review.15 , 16 Formal addiction treatment was defined as a range of providers including opioid treatment programs, inpatient or residential treatment, and outpatient services including intensive outpatient programs, office-based providers of buprenorphine or other forms of treatment. Secondary outcomes, collected by self-report at 2, 6 and 12 months, included the number of days of illicit opioid use in the past 7 days and the summary score of the HIV risk assessment instrument.18 Rates of opioid-negative urine test results were also compared among the study groups at 2 and 6 months.

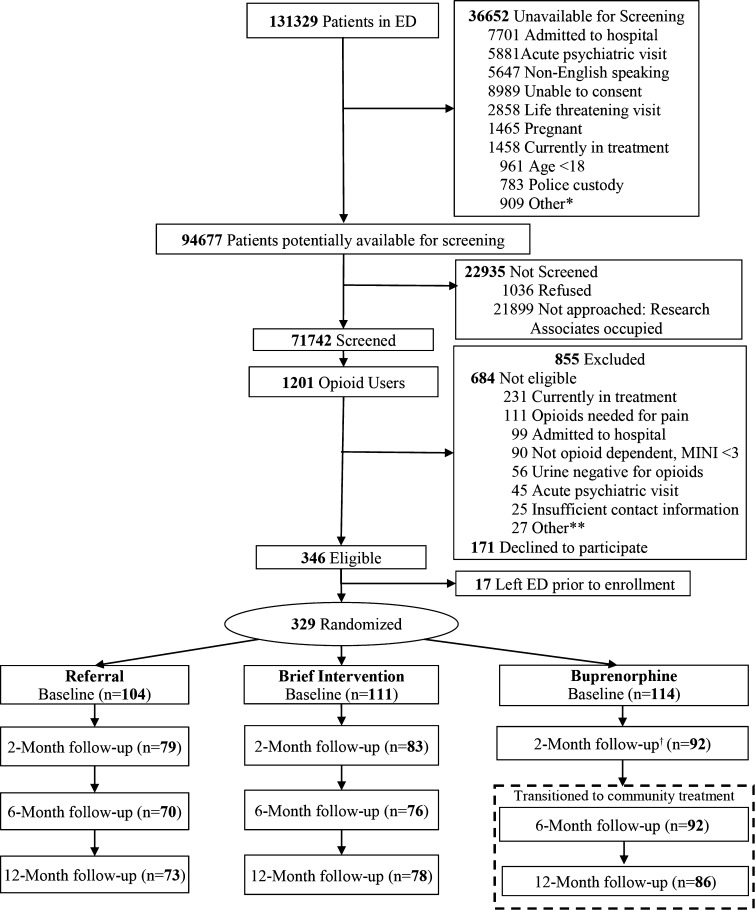

Data Analytical Strategy

The study sample (N = 290) represented 88% of the patients enrolled and randomized in the original trial who provided data during at least one of the 2-, 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments. The numbers of patients in the referral, brief intervention and buprenorphine groups who provided data were 79, 83 and 92 for the 2-month, 70, 75 and 92 for the 6-month, and 73, 78 and 86 for the 12-month assessments, respectively. This followed sample was comparable to the randomized sample on all evaluated characteristics, and there were no statistical differences in follow-up rates across the three groups (p = 0.654; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Enrollment and follow-up flow diagram for trial of interventions for opioid dependence. *Miscellaneous reasons (e.g., isolation, sexual assault, deceased). **Miscellaneous reasons (e.g., unable to consent, non-English-speaking, pregnant, deceased, isolation, age < 18, police custody). †The 2-month follow-up occurred during the 10-week treatment period. --- box represents patients transitioned to non-study community treatment per study protocol. MINI Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Referral referral only, Brief Intervention brief intervention and referral, Buprenorphine ED-initiated buprenorphine and referral.

We used chi-square tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the comparability of the three study groups. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate the statistical significance of between-group differences for all categorical outcomes (e.g., engagement in formal addiction treatment, rates of opioid-negative urine tests) and we used ANOVA to evaluate the statistical significance of between-group differences for all continuous outcomes (e.g., days of illicit opioid use, HIV risk behaviors) at all follow-up assessments. All analyses involved two-tailed tests of significance and were performed using SPSS version 21 software.19

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences among groups. Thirty-three percent were seeking treatment for opioid dependence at the index visit, 9% presented with an overdose, and the remaining 58% were identified through screening. Patients reported substantial use of other substances. Mental health problems were prevalent, with 23% requiring an acute psychiatric evaluation in the ED.

Table 1.

Patient Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Overall (n = 290) no. (%) | Referral (n = 90) no. (%) | Brief intervention (n = 97) no. (%) | Buprenorphine (n = 103) no. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Male sex, no. (%) | 220 (75.9) | 69 (76.7) | 73 (75.3) | 78 (75.7) |

| Race/ethnicity, no. (%) | ||||

| White | 219 (75.5) | 66 (73.3) | 71 (73.2) | 82 (79.6) |

| Black | 19 (6.6) | 6 (6.7) | 6 (6.2) | 7 (6.8) |

| Hispanic | 49 (16.9) | 16 (17.8) | 20 (20.6) | 13 (12.6) |

| Other | 3 (1.0) | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 1 (1.0) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 31.5 (10.0) | 31.9 (10.6) | 31.7 (9.7) | 31.1 (10.0) |

| Education, no. (%) | ||||

| High school graduate or equivalent | 117 (40.3) | 33 (36.7) | 44 (45.4) | 40 (38.8) |

| Some college | 101 (34.9) | 29 (32.3) | 32 (33.0) | 40 (38.8) |

| College degree or more | 19 (6.6) | 8 (8.9) | 8 (8.2) | 3 (2.9) |

| Usual employment, past 3 years, no. (%) | ||||

| Full-time | 148 (51.0) | 48 (53.3) | 49 (50.5) | 51 (49.5) |

| Part-time | 77 (26.6) | 24 (26.7) | 26 (26.8) | 27 (26.2) |

| Married, no. (%) | 32 (11.0) | 10 (11.1) | 8 (8.2) | 14 (13.6) |

| No stable living arrangement, past 30 days, no. (%) | 24 (8.3) | 7 (7.8) | 6 (6.2) | 11 (10.7) |

| Health insurance, no. (%) | ||||

| Private/commercial | 85 (29.3) | 24 (26.7) | 28 (28.9) | 33 (32.0) |

| Medicare | 6 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.1) | 2 (1.9) |

| Medicaid | 131 (45.2) | 45 (50.0) | 41 (42.3) | 45 (43.7) |

| None | 66 (22.8) | 20 (22.2) | 24 (24.7) | 22 (21.4) |

| Primary care physician, no. (%) | 120 (41.4) | 33 (36.7) | 41 (42.3) | 46 (44.7) |

| Usual source of care, no. (%) | ||||

| Private physician’s office | 80 (27.6) | 24 (26.7) | 24 (24.7) | 32 (31.1) |

| Clinic | 76 (26.2) | 23 (25.5) | 28 (28.9) | 25 (24.3) |

| Emergency department or none | 134 (46.2) | 43 (47.8) | 45 (46.4) | 46 (44.6) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| ED identification of patients: | ||||

| Seeking treatment for opioid dependence | 96 (33.1) | 28 (31.1) | 27 (27.8) | 41 (39.8) |

| Identified via screening | 194 (66.9) | 62 (68.9) | 70 (72.2) | 62 (60.2) |

| Overdose | 27 (9.3) | 7 (7.8) | 9 (9.3) | 11 (10.7) |

| Primary type of opioid drug used and route of administration, no. (%) | ||||

| Prescription | 70 (24.1) | 23 (25.6) | 22 (22.7) | 25 (24.3) |

| Heroin | 220 (75.9) | 67 (74.4) | 75 (77.3) | 78 (75.7) |

| Intravenous use | 154 (53.1) | 41 (45.6) | 57 (58.8) | 56 (54.4) |

| Non-opioid substance use, past month, no. (%) | ||||

| Alcohol to intoxication | 102 (35.2) | 31 (34.4) | 41 (42.3) | 30 (29.1) |

| Sedative use | 141 (48.6) | 49 (54.4) | 45 (46.4) | 47 (45.6) |

| Cannabis use | 153 (52.8) | 51 (56.7) | 50 (51.5) | 52 (50.5) |

| Cocaine use | 158 (54.5) | 50 (55.6) | 54 (55.7) | 54 (52.4) |

| Cigarette use | 256 (88.3) | 78 (86.6) | 85 (87.6) | 93 (90.3) |

| Mental health history | ||||

| Lifetime psychiatric treatment, no. (%) | 148 (51.0) | 49 (54.4) | 53 (54.6) | 46 (44.7) |

| Inpatient | 79 (27.2) | 28 (31.1) | 27 (27.8) | 24 (23.3) |

| Outpatient | 123 (42.4) | 44 (48.9) | 41 (42.3) | 38 (36.9) |

| Currently receiving treatment for depression, no. (%) | 37 (12.8) | 8 (8.9) | 15 (15.5) | 14 (13.6) |

| PHQ-9* score, mean (SD) | 12.45 (6.5) | 13.04 (6.4) | 12.17 (6.7) | 12.20 (6.5) |

| Acute psychiatric ED evaluation, no. (%) | 68 (23.4) | 20 (22.2) | 27 (27.8) | 21 (20.4) |

| Lifetime treatment for addiction, no. (%) | ||||

| Alcohol | 42 (14.5) | 17 (18.9) | 16 (16.5) | 9 (8.7) |

| Drugs | 213 (73.4) | 65 (72.2) | 76 (78.4) | 72 (69.9) |

ED emergency department, PHQ-9 Patient Health Questionnaire

*The range of possible scores for the PHQ-9 is 0–27. A score of 5–14 suggests the patient may need treatment based on the duration of symptoms and functional impairment. A score of more than 15 warrants treatment for depression, using antidepressant, psychotherapy and/or a combination of treatment

Outcomes

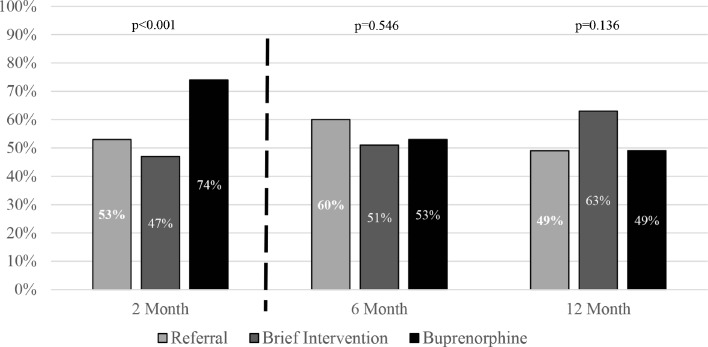

Engagement in Formal Addiction Treatment at the Time of the 2-, 6- and 12-Month Assessment (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Engagement in formal addiction treatment.

Patients in the buprenorphine group were receiving formal addiction treatment at a significantly higher rate at the 2-month assessment [68/92 (74%) 95% CI 65–83] than those in the referral [42/79 (53%), 95% CI 42–64] or brief intervention groups [39/83 (47%) 95% CI 36–58; p < 0.001]. This difference between the buprenorphine, referral and brief intervention groups did not persist at 6 months [49/92 (53%) 95% CI 43–64; 42/70 (60%) 95% CI 48–72; 39/76 (51%) 95% CI 40–63] or 12 months [42/86 (49%) 95% CI 38–60; 36/73 (49%) 95% CI 38–61; 49/78 (63%) 95% CI 52–74; p = 0.546 and p = 0.136, respectively].

Illicit Opioid Use and HIV Risk Behaviors (Table 2)

Table 2.

Past-7-Day Illicit Opioid Use and HIV Risk Behaviors: Baseline and 2, 6 and 12 Months

| Referral | Brief intervention | Buprenorphine | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days of self-reported illicit opioid use in the past 7 days,* mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Baseline | 5.3 (4.9–5.7) | 5.6 (5.3–5.9) | 5.3 (5.0–5.7) | 0.40 |

| 2 Months | 1.8 (1.2–2.4) | 2.0 (1.4–2.6) | 1.1 (0.7–1.5) | 0.04 |

| 6 Months | 1.5 (0.9–2.1) | 2.0 (1.4–2.6) | 1.6 (1.1–2.2) | 0.54 |

| 12 Months | 1.5 (0.9–2.1) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) | 0.7 (0.3–1.2) | 0.09 |

| HIV risk behaviors,† mean (95% CI) | ||||

| Baseline | 8.7 (7.1–10.2) | 9.4 (7.9–10.9) | 9.4 (7.7–11.0) | 0.78 |

| 2 Months | 6.1 (4.6–7.6) | 4.9 (3.8–6.1) | 4.8 (3.7–5.9) | 0.30 |

| 6 Months | 5.4 (3.9–7.0) | 5.3 (3.8–6.7) | 4.4 (3.4–5.4) | 0.45 |

| 12 Months | 3.8 (2.7–4.9) | 5.3 (3.9–6.8) | 4.1 (3.1–5.2) | 0.18 |

*Timeline follow-back method

†HIV Risk Behavior Scale

At 2 months, the buprenorphine group reported significantly less illicit opioid use, with 1.1 (95% CI 0.7–1.5) days of illicit opioid use in the past 7 days, compared with 1.8 (95% CI 1.2–2.4) in the referral group and 2.0 (95% CI 1.4–2.6) in the brief intervention group (p = 0.040). There was a significant temporal trend toward reduction in illicit opioid use in all groups from baseline to 12 months, but there were no longer between-group differences.

There were no statistically significant differences among the three groups regarding HIV risk behaviors at any of the assessment points.

Urine Toxicology

The overall rate of urine sample collection was 224/290 (77%) at 2 months and 194/290 (67%) at 6 months. The rates of illicit opioid-negative urine toxicology tests were not significantly different at 2 months [52/83 (62.7%) in the buprenorphine group, 42/71 (59.2%) in the referral group, and 41/70 (58.6%) in the brief intervention group] or at 6 months [47/74 (63.5%) in the buprenorphine group, 33/59 (55.9%) in the referral group, and 32/61 (52.5%) in the brief intervention group].

DISCUSSION

Opioid-dependent patients who received ED-initiated buprenorphine with continuation in primary care were more likely to be engaged in treatment and reported less use of illicit opioids at the time of follow-up assessments at 2 months. The 2-month assessment occurred while patients were still receiving buprenorphine through primary care, as the study treatment was provided for a total of 10 weeks. These differences in outcomes did not persist at the 6- and 12-month follow-up. After 10 weeks, patients were transitioned to other outpatient treatment providers offering treatments for opioid dependence or were tapered off buprenorphine, depending on patient preference and insurance coverage. It is unlikely that engagement in treatment at 6 and 12 months was related to the ED-initiated buprenorphine or 10-week buprenorphine treatment provided as part of this study. There were no significant differences in HIV risk behaviors or rates of opioid-negative urine test results at any assessment point.

This study demonstrates that the relative benefit of ED-initiated buprenorphine with referral for ongoing treatment in primary care persists at 2 months. Our findings at 2 months in the buprenorphine treatment group are consistent with those of other studies of primary care office-based buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. For example, in a 14-week clinical trial in prescription opioid-dependent individuals, which compared the efficacy of buprenorphine taper versus ongoing maintenance in primary care, 66% of patients in the maintenance group remained in treatment at 14 weeks, compared to 76% at 2 months in our current study.20 Similarly, another study in primary care reported that 78% remained in treatment at 12 weeks.21 Thus, our findings at 2 months are consistent with previous research on the use on buprenorphine in primary care. In the current study, patients in the buprenorphine group were transitioned to other treatment providers or tapered off buprenorphine after 10 weeks. While we do not have information on the specific treatments these patients selected, we do know from previous research that buprenorphine tapering is much less efficacious than ongoing buprenorphine therapy in terms of both treatment retention and illicit opioid use.20 Longer-term outcome studies on buprenorphine in primary care have demonstrated retention rates including 59% at 24 weeks,22 55% at 6 months,23 44% and 57% at 12 months,24 , 25 and 38% at 2 years.26

This study has several limitations. First, this paper reports on a cohort of patients with long-term follow-up, representing 88% of our original randomized trial sample. The 39 patients lost to follow-up (11 buprenorphine, 14 brief intervention, 14 referral) did not differ from the followed cohort with regard to age, gender, type of drugs used, injection drug use, medical insurance status, treatment-seeking status or presentation with an overdose. We also utilized one ED and one site for primary care-based buprenorphine treatment—both of which are located at the same urban academic medical center. Future studies will need to demonstrate that this approach is generalizable to other settings suitable for the provision of buprenorphine treatment in this manner. While the fact that these two sites were part of the same institution may seem to be a limitation of the study, it may also serve as a model for how these services can be effectively integrated within a medical center or health care system that provides comprehensive health care services. Such models are becoming increasingly prevalent as consolidation occurs within the U.S. health care system. In addition, the data regarding engagement in formal addiction treatment at 2, 6 and 12 months are based on self-report and were not confirmed with treatment providers. We attempted to limit bias and social desirability by completing 2- and 6-month assessments in a clinical setting separate from primary care or other treatment sites conducted by RAs not involved in any aspect of their care. Patients were informed that their answers and urine test results were confidential and were stored in de-identified (anonymous) form in the data sets, and that reimbursement for their time was not dependent on their responses.

We focused on engagement in treatment at specific time points, which does not take into consideration that patients may have been engaged in treatment at other times. While this may underestimate the true proportion of patients engaged in treatment, we believe this is appropriate given the relapsing nature of opioid use disorder. The outcomes observed in the referral and brief intervention groups may appear better than expected. This could be due to the extent to which these conditions provided resources that are beyond usual care, the availability of treatment resources in the surrounding area, or other unmeasured confounders. To our knowledge, no other study has followed an ED population of patients with opioid use disorder up to 12 months. Either way, these factors would bias against a positive finding with the ED-initiated buprenorphine treatment condition. Finally, we were able to obtain urine samples for opioids on only a subset of patients at 2 and 6 months, leading to the potential for bias. For this reason, and since urine tests assess opioid use only within the prior 72 hours, we caution against placing undue emphasis on these findings or the discrepancy between urine testing and self-report of drug use, which was assessed over a longer 7-day time frame.

Despite these limitations, our study provides evidence that ED-initiated buprenorphine treatment with linkage to ongoing treatment in primary care increases engagement in formal addiction treatment and reduces self-reported illicit opioid use while such treatment is continued. For 27% of the enrolled ED patients, the index ED visit represented their first treatment contact. Thus, the ED visit is an opportunity to engage patients with opioid use disorder in effective medication-assisted treatment. Future research should focus on evaluating the implementation of this model in a diverse array of emergency departments and other health care settings.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

GD, MC, PGO, SHB, PHO, SLB and DF were involved in the study conception, and obtained funding; GD, PGO, MP, PHO, SLB and DF supervised the conduct of the trial and data collection; MC and PHO managed the data, including quality control; MC and SHB provided statistical advice on study design and analyzed the data; all authors were involved in interpreting the data; GD, MC, PGO, PHO, KH and DF drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision; GD and DF take responsibility for the paper as a whole. There are no others to report, aside from research staff who collected data.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Fiellin has received honoraria from Pinney Associates for serving on an external advisory board monitoring the diversion and abuse of buprenorphine. The remaining authors have no conflicts.

Funders

The study was supported by grants 5R01DA025991 and K12DA033312 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals provided buprenorphine through NIDA. The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Prior Presentation

The College on Problems of Drug Dependence, June 2015, Phoenix, Arizona.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier

NCT0091377

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control, Prevention Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs - United States, 2004–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(23):705–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control, Prevention CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses - a U.S. epidemic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(1):10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surgeon General Report: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health, Executive Summary. Washington, DC: HHS, November 2016. [PubMed]

- 4.Gowing L, Farrell MF, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali R. Oral substitution treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD004145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004145.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonymous . Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR: Text Revision: American Psychiatric Press Incorporated (DC); 2000.

- 8.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice. Lancet. 2002;359(9305):515–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07683-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Onofrio G, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, et al. Brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(6):742–50. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Onofrio G, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, et al. Development and implementation of an emergency practitioner-performed brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(3):249–56. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wesson DR, Ling W. The clinical opiate withdrawal scale (COWS) J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253–9. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JD, Grossman E, DiRocco D, Gourevitch MN. Home buprenorphine/naloxone induction in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):226–32. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0866-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, et al. A randomized trial of cognitive behavioral therapy in primary care-based buprenorphine. Am J Med. 2013;126(1):74–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(4):365–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLellan TA, Zanis D, Incmikoski R. Treatment Service Review (TSR) Philadelphia: The Center for Studies in Addiction, Department of Psychiatry: Philadelphia VA Medical Center & The University of Pennsylvania; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLellan AT, Alterman AI, Cacciola J, Metzger D. A new measure of substance abuse treatment. Initial studies of the treatment services review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180(2):101–10. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobell L, Sobell M. Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, Ward J, Wodak A. The reliability and validity of a scale to measure HIV risk taking behaviour among intravenous drug users. Aids. 1991;5(2):181–186. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- 20.Fiellin DA, Schottenfeld RS, Cutter CJ, Moore BA, Barry DT, O’Connor PG. Primary care–based buprenorphine taper vs maintenance therapy for prescription opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1947–54. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor P, Oliveto A, Shi J, et al. A randomized trial of buprenorphine maintenance for heroin dependence in a primary care clinic for substance users versus a methadone clinic. Am J Med. 1998;105(2):100–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(98)00194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein MD, Cioe P, Friedmann PD. Buprenorphine retention in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1038–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0228.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki J, Matthews ML, Brick D, et al. Implementation of a collaborative care management program with buprenorphine in primary care: a comparison between opioid-dependent patients and chronic pain patients using opioids non-medically. J Opioid Manag. 2014;10(3):159. doi: 10.5055/jom.2014.0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soeffing JM, Martin LD, Fingerhood MI, Jasinski DR, Rastegar DA. Buprenorphine maintenance treatment in a primary care setting: outcomes at 1 year. J Subst Abus Treat. 2009;37(4):426–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Kretsch N, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):425–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiellin DA, Moore BA, Sullivan LE, et al. Long-term treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in primary care: results at 2–5 years. Am J Addict. 2008;17(2):116–20. doi: 10.1080/10550490701860971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]