Abstract

Background

Pregnancy and its impact on graduate medical training are not well understood.

Objective

To examine the effect of gender and pregnancy for Internal Medicine (IM) residents on evaluations by peers and faculty.

Design

This was a retrospective cohort study.

Subjects

All IM residents in training from July 1, 2004–June 30, 2014, were included. Female residents who experienced pregnancy and male residents whose partners experienced pregnancy during training were identified using an existing administrative database.

Main Measures

Mean evaluation scores by faculty and peers were compared relative to pregnancy (before, during, and after), accounting for the gender of both the evaluator and resident in addition to other available demographic covariates. Potential associations were assessed using mixed linear models.

Key Results

Of 566 residents, 117 (20.7%) experienced pregnancy during IM residency training. Pregnancy was more common in partners of male residents (24.7%) than female residents (13.2%) (p = 0.002). In the post-partum period, female residents had lower peer evaluation scores on average than their male counterparts (p = 0.0099).

Conclusions

A large number of residents experience pregnancy during residency. Mean peer evaluation scores were lower after pregnancy for female residents. Further study is needed to fully understand the mechanisms behind these findings, develop ways to optimize training throughout pregnancy, and explore any unconscious biases that may exist.

KEY WORDS: graduate medical education, pregnancy, evaluation

INTRODUCTION

Increasing numbers of women experience pregnancy during medical training.1 In recent studies, female trainees with a pregnancy during residency ranged from 9–14%.2 , 3 Meanwhile, data on the rate of pregnancy in partners of male residents are limited with one study reporting 27%.3 Understanding the impact of pregnancy on graduate medical education is important to inform policy and curricular changes to support the needs and goals of trainees.

Cross-sectional observation-based studies have solicited opinions on how pregnancy impacts pregnant residents and their colleagues. Pregnant residents have self-reported experiencing criticism or conflict with staff as a result of their pregnancy.4 – 7 Furthermore, male colleagues have reported a negative impact on working relationships with pregnant residents.8 In contrast, other studies have demonstrated perceptions of supportive colleagues.9 , 10 Some colleagues reported that their workload was increased as a result of working with a pregnant resident.11 Ultimately, in a single study of female pediatricians who had completed residency, over one third would not choose to be pregnant during residency if they “had it to do over again.”12 However, few objective data exist regarding the impact of pregnancy on trainees and colleagues during residency. Moreover, we are unaware of existing data regarding the impact of pregnancy on faculty and peer evaluations of trainee clinical performance.

The objective of this study is to assess the performance evaluations by attending staff physicians and peer resident colleagues of residents experiencing pregnancy during Internal Medicine residency. Specifically, we sought to answer: (1) whether gender and pregnancy are associated with mean evaluation scores during IM residency, and (2) do these potential associations differ by the role of the evaluator (peer vs. faculty)?

METHODS

Subjects and Independent Variables

The Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Residency in Rochester, Minnesota, offers 48 categorical positions each year. This is a large tertiary academic center. The evaluation timeframe for this study included 10 academic years, from July 1, 2004, through June 30, 2014, which overlapped at least 1 year of training for 12 resident classes (2005–2016). We identified pregnancies for female trainees as well as male trainees with a pregnant partner by reviewing resident electronic absence requests, which were required for all residents requesting absences. Delivery dates also were determined by the electronic absence request. Evaluations for residents who experienced pregnancy were categorized as occurring prior to, during, or after pregnancy. Age, international medical graduate status (IMG), post-graduate year (PGY)-1 In-Training Examination (ITE) score, and the PGY of training during evaluation completion were assessed as potential covariates based on previous work.13 All variables were available on each resident from existing administrative databases as part of the usual educational processes of the residency. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Outcome Variable

The Integrated Scheduling and Evaluation System (ISES) was the single electronic system for completion of evaluations of internal medicine residents as part of their regular educational activities at Mayo Clinic during the study period. It has been demonstrated to have a high level of reliability14. These evaluations are designed to evaluate residents based on the competencies delineated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and included 7–12 questions scored on a 5-point Likert scale (higher scores indicate a better evaluation score). During residency, residents undergo multi-source evaluations by all attending physicians and resident colleagues who they work with. Evaluations are completed anonymously. The evaluations were de-identified and tracked using numerical codes assigned by support staff and unknown to the study investigators. Likert scaled responses to questions on each evaluation were aggregated to create a continuous valued numeric average score for each completed evaluation, which served as the observational unit for all subsequent analyses.

Statistical Analysis

Potential differences in mean evaluation scores (ignoring pregnancy) for the four resident-evaluator gender pairings were assessed for both peer and faculty using t tests for each pairwise least squares mean. Likewise, the potential effect of PGY was assessed. Multivariable analyses using mixed linear models were used to assess the effect of evaluation timing with respect to pregnancy on mean evaluation scores, adjusting for available demographics, including resident-evaluator gender pairings. Repeated assessments were accounted for by including random effects for both evaluators and residents using a variance components covariance structure. To account for multiple comparisons, a significance level of α = 0.01 was used throughout. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS statistical software (Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Cohort Demographics

During the 10-year study period, a total of 566 residents [369 (65.2%) male, 197 (34.8%) female] trained in the Internal Medicine residency program. The average age at matriculation was 27.7 years, the average percent correct on the IM ITE as PGY-1 s was 63.2%, and 75 (13.3%) residents were IMGs. A total of 117 (20.7%) experienced pregnancies during this time, 26 (13.2%) by female residents and 91 (24.7%) by male resident partners (p = 0.002). There were no differences in mean (SD) age [27.8 (3.3) vs. 27.5 (3.1) years], number (%) of IMGs [49 (13.3%) vs. 26 (13.2%)], or mean (SD) difference in PGY-1 In-Training-Examination (ITE) percent correct [63.6 (7.2) vs. 62.4 (6.9)] between male and female residents, respectively (all p ≥ 0.05). Male residents whose partner had a pregnancy (N = 91) tended to be older than male residents whose partner did not (N = 278) [28.8 (2.7) vs. 27.4 (3.5) years; p = 0.0001]. No other significant differences in demographics were found between any combination of gender and pregnancy experience.

Peer Evaluation: Overall

There were a total of 25,487 peer evaluations of residents during the study timeframe, with an overall mean (SD) of 4.11 (0.61). Male residents received a higher mean (SE) evaluation score from male peer evaluators than they did from female peer evaluators [4.130 (0.019) vs. 4.071 (0.022), p = 0.009], with a Cohen’s d effect size of 0.1. There was no difference in ratings of female residents by peer evaluator gender (p = 0.51).

Faculty Evaluation: Overall

There were a total of 48,148 faculty evaluations of residents during the study timeframe, with an overall mean (SD) of 3.97 (0.56). Female and male residents had similar mean ratings by faculty evaluators regardless of faculty evaluator gender (all p ≥ 0.04). Over the timeframe of residency training, faculty evaluation scores increased from the PGY-1 to PGY-3 year for all gender pairings of evaluator and resident.

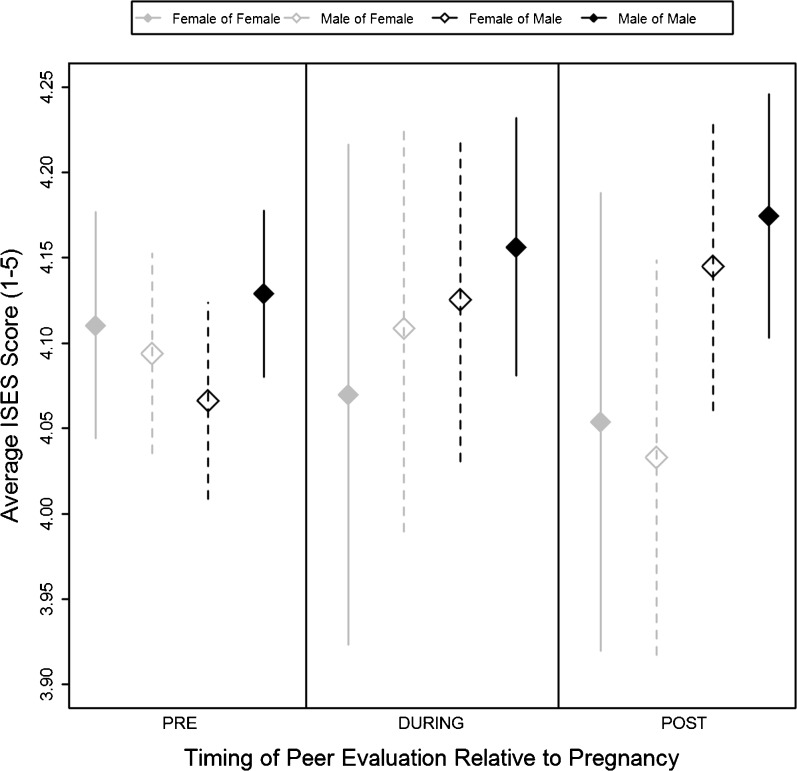

Peer Evaluations and Residents Experiencing Pregnancy

Of the peer evaluations, 21,988 (86%) were ‘Pre,’ 1238 (5%) were ‘During,’ and 2261 (9%) were ‘Post’ pregnancy. The number (%) of evaluations of female residents by timing relative to pregnancy was 8433 (38%), 304 (25%), and 461 (20%), respectively. A mixed linear model for mean evaluation scores by peers was fit to the data, adjusting for potential differences by age, IMG status, ITE percent correct (p < 0.0001), PGY (p = 0.0004 for PGY-1, p = 0.002 for PGY-3, vs. PGY-2, respectively), evaluated resident gender, peer evaluator gender (p = 0.006), resident-peer gender pairing (p < 0.0001), pregnancy status, evaluated resident gender and peer evaluator gender by pregnancy status interactions, and resident-peer gender pairing by pregnancy status interaction (Table 1). Adjusted least squares mean peer evaluation scores were estimated for the four resident-peer gender pairings by pregnancy status (Fig. 1). For evaluations completed in the absence of pregnancy, there was a significant resident-peer gender pairing interaction effect (p < 0.0001), which was not found to be present during (p = 0.56) or after (p = 0.03) pregnancy. The estimated mean (SE) peer evaluation scores before pregnancy were 4.07 (0.02) for male of female, 4.09 (0.02) for female of male, 4.11 (0.03) for female of female, and 4.13 (0.02) for male of male. A significant effect attributed to evaluated resident gender was seen for evaluations completed after pregnancy (p = 0.0099), which was not seen either during (p = 0.27) or before (p = 0.84) pregnancy. The estimated mean (SE) evaluation scores after pregnancy were 4.04 (0.04) for female residents and 4.16 (0.03) for male residents. The estimated effect size using Cohen’s f2 for multiple linear regression was 0.003.

Table 1.

Parameter estimates from a mixed linear model of peer evaluations (N = 25,487)

| Variable | Category | β (SE) | T test P-value | F test P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (βo) | 4.151 (0.020) | <0.0001 | ||

| International medical graduate | −0.037 (0.032) | 0.2509 | 0.25 | |

| Age at matriculation, years | −0.006 (0.003) | 0.0703 | 0.07 | |

| PGY-1 I.E. percent correct | 0.007 (0.002) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Role of evaluatee | Of PGY-1 | −0.030 (0.009) | 0.0004 | 0.0005 |

| Of PGY-3 | −0.029 (0.009) | 0.0015 | ||

| Of PGY-2 | – | |||

| Gender of evaluatee | Of female | −0.035 (0.023) | 0.1361 | 0.07 |

| Of male | – | |||

| Gender of evaluator | By female | −0.063 (0.023) | 0.0063 | 0.42 |

| By male | – | |||

| Timing, relative to pregnancy | After | 0.046 (0.024) | 0.0577 | 0.76 |

| During | 0.027 (0.025) | 0.2789 | ||

| Prior | – | |||

| Gender pairing of evaluation | Female of female | 0.079 (0.015) | <0.0001 | 0.18 |

| Male of female | – | |||

| Female of male | – | |||

| Male of male | – | |||

| Evaluatee gender by timing | Of female, after | −0.107 (0.047) | 0.0229 | 0.0168 |

| Of female, during | −0.013 (0.049) | 0.7996 | ||

| Of female, prior | – | |||

| Of male, after | – | |||

| Of male, during | – | |||

| Of male, prior | – | |||

| Evaluator gender by timing | By female, after | 0.033 (0.027) | 0.2135 | 0.75 |

| By female, during | 0.032 (0.036) | 0.3718 | ||

| By female, prior | – | |||

| By male, after | – | |||

| By male, during | – | |||

| By male, prior | – | |||

| Gender pairing by timing | Female of female, after | −0.029 (0.057) | 0.6121 | 0.42 |

| Female of female, during | −0.088 (0.071) | 0.2158 | ||

| Female of female, prior | – | |||

| Male of female, after | – | |||

| Male of female, during | – | |||

| Male of female, prior | – | |||

| Female of male, after | – | |||

| Female of male, during | – | |||

| Female of male, prior | – | |||

| Male of male, after | – | |||

| Male of male, during | – | |||

| Male of male, prior | – |

Figure 1.

Adjusted peer ratings by gender pairing by timing relative to pregnancy. *The “PRE” timeframe includes all peer evaluations of residents who did not experience a pregnancy during residency. Vertical lines reflect 99% confidence intervals around the estimated least squares means

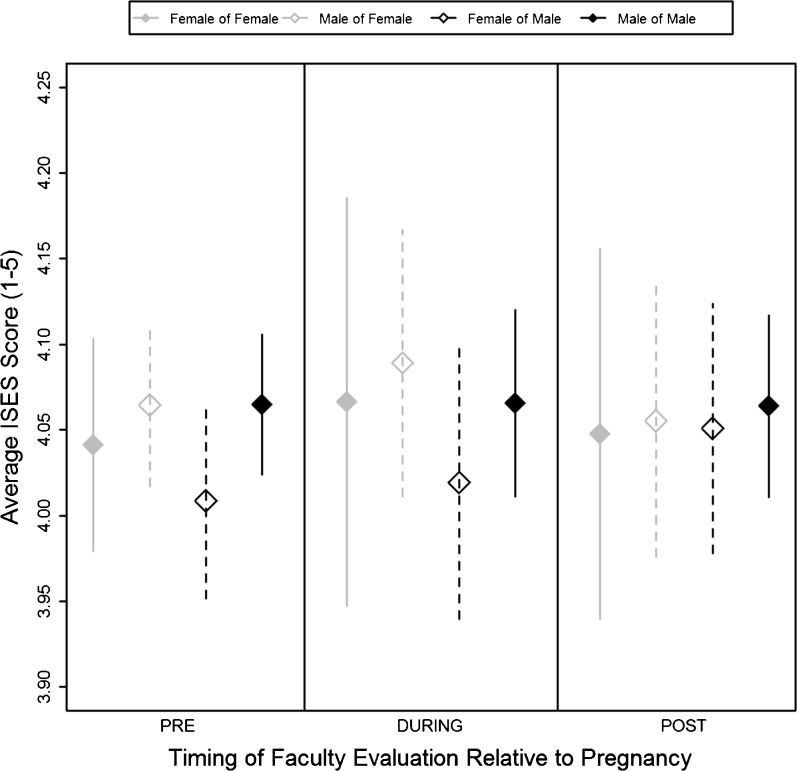

Faculty Evaluations and Residents Experiencing Pregnancy

Of the faculty evaluations, 41,626 (86%) were ‘Pre,’ 2309 (5%) were ‘During,’ and 4213 (9%) were ‘Post’ pregnancy. The number (%) of evaluations of female residents by timing relative to pregnancy was 15,882 (38%), 580 (25%), and 818 (19%), respectively. A mixed linear model for mean evaluation scores by faculty was fit to the data, adjusting for potential differences by age (p = 0.004), IMG status, ITE percent correct (p < 0.0001), PGY (p < 0.0001 for both PGY-1 and -3, vs. PGY-2), evaluated resident gender, faculty evaluator gender, resident-faculty gender pairing (p = 0.001), pregnancy status, evaluated resident gender and faculty evaluator gender by pregnancy status interactions, and resident-faculty gender pairing by pregnancy status interaction (Table 2). Adjusted least squares mean faculty evaluation scores were estimated for the four resident-faculty gender pairings by pregnancy status (Fig. 2). For evaluations completed in the absence of pregnancy, there was a significant resident-faculty gender pairing interaction effect (p = 0.003), which was not found to be present during (p = 0.41) or after (p = 0.97) pregnancy. The estimated mean (SE) faculty evaluation scores before pregnancy were 4.01 (0.02) for male of female, 4.04 (0.02) for female of female, 4.06 (0.02) for female of male, and 4.06 (0.02) for male of male. No other significant effects were observed related to gender or pregnancy. The estimated effect size using Cohen’s f2 for multiple linear regression was 0.03.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates from a mixed linear model of faculty evaluations (N = 48,148)

| Variable | Category | β (SE) | T test P-value | F test P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (βo) | 4.068 (0.017) | <0.0001 | ||

| International medical graduate | 0.020 (0.024) | 0.4015 | 0.40 | |

| Age at matriculation, years | −0.007 (0.002) | 0.0042 | 0.004 | |

| PGY-1 I.E. percent correct | 0.005 (0.001) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Role of evaluatee | Of PGY-1 | −0.119 (0.006) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Of PGY-3 | 0.094 (0.006) | <0.0001 | ||

| Of PGY-2 | – | . | ||

| Gender of evaluatee | Of female | −0.0005 (0.017) | 0.9784 | 0.49 |

| Of male | – | . | ||

| Gender of evaluator | By female | −0.056 (0.024) | 0.018 | 0.27 |

| By male | – | . | ||

| Timing, relative to pregnancy | After | −0.0009 (0.016) | 0.9564 | 0.60 |

| During | 0.0009 (0.016) | 0.9556 | ||

| Prior | – | . | ||

| Gender pairing of evaluation | Female of female | 0.033 (0.010) | 0.0011 | 0.32 |

| Male of female | – | . | ||

| Female of male | – | . | ||

| Male of male | – | . | ||

| Evaluatee gender by timing | Of female, after | −0.008 (0.030) | 0.7831 | 0.46 |

| Of female, during | 0.024 (0.030) | 0.4274 | ||

| Of female, prior | – | . | ||

| Of male, after | – | . | ||

| Of male, during | – | . | ||

| Of male, prior | – | . | ||

| Evaluator gender by timing | By female, after | 0.043 (0.019) | 0.0206 | 0.34 |

| By female, during | 0.010 (0.025) | 0.6975 | ||

| By female, prior | – | . | ||

| By male, after | – | . | ||

| By male, during | – | . | ||

| By male, prior | – | . | ||

| Gender pairing by timing | Female of female, after | −0.028 (0.040) | 0.4861 | 0.78 |

| Female of female, during | −0.009 (0.050) | 0.8555 | ||

| Female of female, prior | – | . | ||

| Male of female, after | – | . | ||

| Male of female, during | – | . | ||

| Male of female, prior | – | . | ||

| Female of male, after | – | . | ||

| Female of male, during | – | . | ||

| Female of male, prior | – | . | ||

| Male of male, after | – | . | ||

| Male of male, during | – | . | ||

| Male of male, prior | – | . |

Figure 2.

Adjusted faculty ratings by gender pairing by timing relative to pregnancy. *The “PRE” timeframe includes all faculty evaluations of residents who did not experience a pregnancy during residency. Vertical lines reflect 99% confidence intervals around the estimated least squares means

DISCUSSION

This study sought to evaluate how internal medicine resident evaluations are affected by pregnancy. Female residents who experience pregnancy during residency received lower peer evaluation scores following pregnancy as compared to males.

This work supplements previous survey-based studies evaluating the impact of pregnancy on physician interactions.4 , 5 , 8 – 11 This study extends our understanding of the impact of pregnancy on residency by utilizing real-time resident peer and faculty evaluation score data that are routinely collected as part of the resident evaluation process during training, while accounting for potential factors including resident age, baseline medical knowledge, IMG status, and PGY level. Comparing evaluations of pregnant female residents versus male residents with pregnant partners provides unique insight into potential gender-based disparate perceptions among colleagues undergoing a significant life event, and these unconscious biases can be addressed at the curricular level.

Previous survey-based studies have highlighted a perception of hostility toward female trainees during their pregnancy from faculty.5 , 7 , 9 There also have been consistent findings of discordance of perceptions when comparing pregnant female trainees, peer colleagues, and program directors.7 , 8 , 11 , 15 One study interestingly found that the majority felt that pregnancy had a “positive or humanizing effect on the work environment.”16 We observed no difference in faculty evaluations of female residents after pregnancy compared to male residents whose partner had given birth but did see a reduction from peer evaluators. It is unclear if this difference is reflective of the variable study design, contrasting survey data versus real-time evaluations, or the more recent time of this study.

This study also evaluated the interaction of the gender of the evaluator and resident, which identified differences between peers in contrast to faculty. There have been contrasting data in the literature regarding the impact of gender on evaluations in graduate medical education.17 , 18 Ongoing research is needed to further understand the impact of gender on evaluations.

Fortunately, there is a suggestion of progress addressing the stigmatization of pregnancy felt by female physicians.4 However, the perception of pregnancy during residency remains complicated as evidenced in a recent article by its inclusion in a list of “social problems” alongside drug and alcohol abuse that impacts plastic surgery program directors.19 Different types of assessment are needed to fully understand the impact of pregnancy and parenthood and supplement prior data about the impact of parenthood and its association with ITE scores.20

The next step after understanding the impact of pregnancy for residents and programs is to utilize this to inform curriculum and policy change and explore the influence of any unconscious bias. Qualitative data regarding concerns of balance between career and parenting in female residents have led to unique curriculum changes at a training program concerning rotational location, which has been demonstrated to be effective in changing the perception of pregnancy by residents.21 A reduction in work hours in one program was associated with fewer negative attitudes toward pregnancy during training.22

Changes in parental policy are a visible product of studying the impact of pregnancy on graduate medical education. Dating back to 1986, only 20% of residencies affiliated with one university had a maternal leave policy.7 This is in contrast to the most recent Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM) annual survey in 2014 with 79% of program directors reporting a written maternity policy and 59% having a written paternity policy.24 Further, time for maternity leave has increased over time in one study of female matriculants of a single medical school.1 In the APDIM 2014 survey, the mean (SD) maternity leave was 6.1 (4.0) weeks while paternity leave was 5.6 (7.8) days.23 In comparison, in the US from 2006–2008, 70.6% of employed women reported a maternity leave with average length of 10.3 weeks.24 Recently, our program has made a change to its policy to increase the allowable parental leave for both male and female trainees.

In terms of limitations, other uncontrolled variables, such as medical complications for the mother or baby, history of prior children, and partner support, which could have a significant impact on a resident, were not captured. However, the focus of this article was to identify trends that could encourage future research into effective support programs for trainees in graduate medical education who would like to have a child. Also, some changes in terms of absolute values were low in scenarios that were found to be statistically significant.

This study demonstrates the need for further research on the impact of pregnancy on colleague interactions and further development of effective programs to support residents regarding childcare. Further evaluation is needed to understand programmatic interventions for both female and male residents to feel supported in any decision regarding family planning.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: None.

This study was supported in part by the Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Residency Office of Educational Innovations as part of the Educational Innovations Project of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

Prior presentations: None.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Potee RA, Gerber AJ, Ickovics JR. Medicine and motherhood: shifting trends among female physicians from 1922 to 1999. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 1999;74:911–919. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199908000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hutchinson AM, Anderson NS, 3rd, Gochnour GL, Stewart C. Pregnancy and childbirth during family medicine residency training. Family medicine. 2011;43:160–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabbe SG, Morgan MA, Power ML, Schulkin J, Williams SB. Duty hours and pregnancy outcome among residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2003;102:948–951. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00856-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner PL, Lumpkins K, Gabre J, Lin MJ, Liu X, Terrin M. Pregnancy among women surgeons: trends over time. Archives of surgery. 2012;147:474–479. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart DE, Robinson GE. Combining motherhood with psychiatric training and practice. Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 1985;30:28–34. doi: 10.1177/070674378403000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finch SJ. Pregnancy during residency: a literature review. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2003;78:418–428. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200304000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sayres M, Wyshak G, Denterlein G, Apfel R, Shore E, Federman D. Pregnancy during residency. The New England journal of medicine. 1986;314:418–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198602133140705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamburrino MB, Evans CL, Campbell NB, Franco KN, Jurs SG, Pentz JE. Physician pregnancy: male and female colleagues’ attitudes. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association. 1992;47:82–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phelan ST. Sources of stress and support for the pregnant resident. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 1992;67:408–410. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199206000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gjerdingen DK, Chaloner KM, Vanderscoff JA. Family practice residents’ maternity leave experiences and benefits. Family medicine. 1995;27:512–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merchant SJ, Hameed SM, Melck AL. Pregnancy among residents enrolled in general surgery: a nationwide survey of attitudes and experiences. Am J Surg. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Klevan JL, Weiss JC, Dabrow SM. Pregnancy during pediatric residency. Attitudes and complications. American journal of diseases of children. 1990;144:767–769. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150310035021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thackeray EW, Halvorsen AJ, Ficalora RD, Engstler GJ, McDonald FS, Oxentenko AS. The effects of gender and age on evaluation of trainees and faculty in gastroenterology. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2012;107:1610–1614. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckman TJ, Mandrekar JN, Engstler GJ, Ficalora RD. Determining reliability of clinical assessment scores in real time. Teaching and learning in medicine. 2009;21:188–194. doi: 10.1080/10401330903014137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balk SJ, Christoffel KK, Bijur PE. Pediatricians’ attitudes concerning motherhood during residency. American journal of diseases of children. 1990;144:770–777. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1990.02150310038022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franco K, Evans CL, Best AP, Zrull JP, Pizza GA. Conflicts associated with physicians’ pregnancies. The American journal of psychiatry. 1983;140:902–904. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.7.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmboe ES, Huot SJ, Brienza RS, Hawkins RE. The association of faculty and residents’ gender on faculty evaluations of internal medicine residents in 16 residencies. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009;84:381–384. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181971c6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brienza RS, Huot S, Holmboe ES. Influence of gender on the evaluation of internal medicine residents. Journal of women’s health. 2004;13:77–83. doi: 10.1089/154099904322836483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verheyden CN, McGrath MH, Simpson P, Havens L. Social problems in plastic surgery residents: a management perspective. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015;135:772e–778e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Factors associated with medical knowledge acquisition during internal medicine residency. Journal of general internal medicine. 2007;22:962–968. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0206-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole S, Arnold M, Sanderson A, Cupp C. Pregnancy during otolaryngology residency: experience and recommendations. The American surgeon. 2009;75:411–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols M. Curriculum change in an obstetrics-gynecology residency program and its impact on pregnancy in residency. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1994;170:1658–1664. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(12)91831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine. 2014 APDIM Program Directors Survey-Summary File. 2014.

- 24.US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau . Women’s Health USA 2011. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]