Abstract

This study investigated molecular signals essential to sustain cancer stem cells (CSCs) and assessed their activity in the presence of secreted frizzled-related protein 4 (sFRP4) alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs. SFRP4 is a known Wnt antagonist, and is also pro-apoptotic and anti-angiogenic. Additionally, sFRP4 has been demonstrated to confer chemo-sensitization and improve chemotherapeutic efficacy. CSCs were isolated from breast, prostate, and ovary tumor cell lines, and characterized using tumor-specific markers such as CD44+/CD24−/CD133+. The post-transcription data from CSCs that have undergone combinatorial treatment with sFRP4 and chemotherapeutic drugs suggest downregulation of stemness genes and upregulation of pro-apoptotic markers. The post-translational modification of CSCs demonstrated a chemo-sensitization effect of sFRP4 when used in combination with tumor-specific drugs. SFRP4 in combination with doxorubicin/cisplatin reduced the proliferative capacity of the CSC population in vitro. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is important for proliferation and self-renewal of CSCs in association with human tumorigenesis. The silencing of this signaling pathway by the application of sFRP4 suggests potential for improved in vivo chemo-responses.

Introduction

Chemotherapy, along with radiotherapy and hormone therapy, is the most common treatment for cancer. Due to the side effects of treatment and chemo-resistance of tumor cells, researchers have shifted their focus to more site-specific treatments in order to achieve better patient outcomes1. Over the past decade, a critical role of a small subset of tumor cells, known as cancer stem cells (CSCs), was established in tumor relapse and propagation2, 3. Most solid tumors, including breast, brain, prostate, ovary, mesothelioma, and colon cancer contain this small subset of self-renewing, tumor initiating cells4. Conventional anti-cancer therapies inhibit/kill the bulk of the heterogeneous tumor mass, resulting in tumor shrinkage. However, it has been suggested that later, the CSCs differentiate into tumor cells and are responsible for tumor relapse5, 6. CSCs are characterized by their tumor forming ability and expression of high levels of ATP-binding cassette drug transporters (ABCG2), cell adhesion molecules (CD44), and anchorage independent cell survival proteins (Cyclin D1), which are collectively responsible for chemo-resistance7–9. In human breast, ovary, and prostate cancers, several CSC populations have been identified using cell surface markers (CD44+/CD133+/CD24−/low); these CSCs have shown a high clonal, invasive, and metastatic capacity, leading to resistance to radio-therapy, chemotherapeutic drugs (doxorubicin and cisplatin), and other target-specific therapy10–12.

CSCs possess high capacity for tumor propagation and metastasis13–15, which causes more than 90% of cancer-related deaths. The molecular mechanism of CSCs regulating metastasis is not completely understood; however, the invasive metastatic cascade involves circulation of cancer cells through the surrounding extracellular matrix in a multistep cellular operation.

The development and maintenance of CSCs is controlled by several signaling pathways such as Wnt and Notch. The Wnt pathway is known to mediate the self-renewal capacity of CSCs through modulation of β-catenin/TCF transcription factors. There is evidence suggesting a Wnt signaling role in CSC maintenance (as seen in murine models and humans) of non-melanoma cutaneous tumor, where CSCs are maintained by Wnt/β-catenin signaling16. The interactions of Wnt proteins to the receptor complex can be inhibited by binding of the ligands to endogenous Wnt antagonists such as secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRPs)17. SFRP4 is one of the prominent isoforms with the capacity to chemo-sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapeutics18, 19. Chemo-sensitization of CSCs by sFRP4 has the potential to decrease the required chemotherapeutic load to facilitate tumor resolution.

Results

Tumor derived CSCs characterization

Spheroids obtained for CSC isolation were characterized for the expression of tumor-specific CSC markers CD44+ / CD24−/low for breast CSCs, and CD133+/CD44+ for prostate and ovarian CSCs (Table 1), by using flow cytometry. The combinatorial treatment showed significant reduction in the CSC marker population in all cell line-derived CSCs; although in A2780 prostate CSCs, cisplatin treatment showed phenotype switching to CD44+ positive cells and only reduced the CD133+ population; however, this switching did not affect the inhibitory effect of combinatorial treatment (see Supplementary Figure 1). The characterized CSCs were further used for functional analysis.

Table 1.

Effect of sFRP4 on CSCs characterization.

| Treatment | Surface markers | CD44+/CD24− (%) | CD133+/CD44+ (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDA231 | MCF7 | PC3 | LnCap | A2780 P | A2780 ADR | A2780 CIS | ||

| Untreated | 58.1 | 36.7 | 24.3 | 62.7 | 2.85 | 19.5 | 2.72 | |

| sFRP4 | 32.3 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 44.1 | 2.99 | 16.8 | 2.21 | |

| Dox./Cisplatin | 28.5 | 14.9 | 22.1 | 47.5 | 9.29 | 16 | 1.8 | |

| sFRP4 + Dox./Cisplatin | 25 | 1.68 | 9.16 | 10.4 | 1.88 | 15.1 | 1.23 | |

Using flow cytometry, Statistical analysis of CSC markers post treatment. Data are means ± percentage from 3 independent experiments.

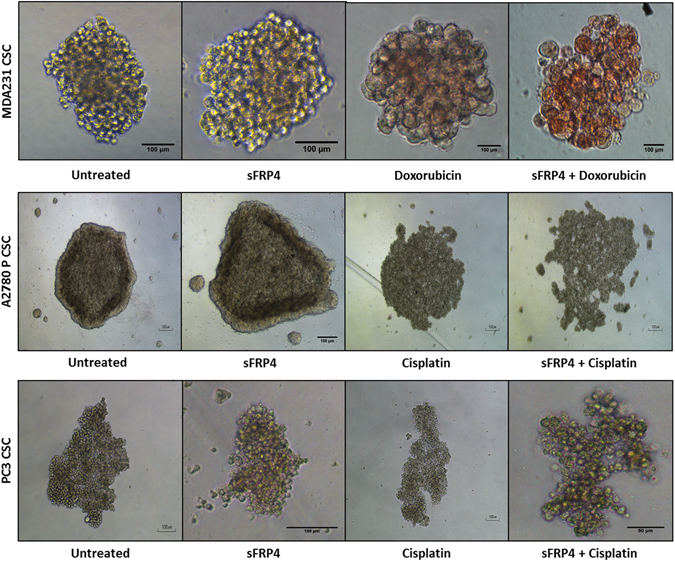

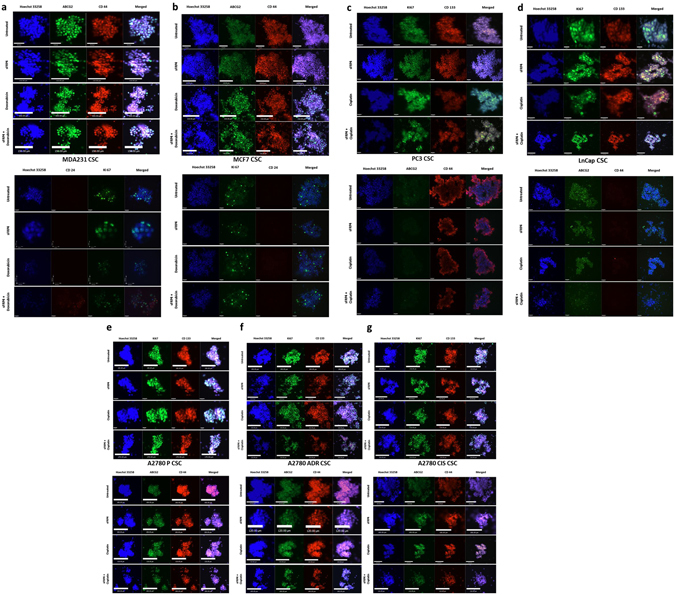

SFRP4 in combination with doxorubicin/cisplatin reduces the sphere forming capacity of CSCs

The CSCs derived from breast, prostate, and ovary tumor cell lines were treated with sFRP4 (250 pg) and doxorubicin (5 μM)/cisplatin (30 μM) alone or in combination. The untreated spheroids remained intact, whereas the combinatorial treatment of sFPR4 and chemotherapeutic drugs showed disruption of spheroids post-treatment (Fig. 1), indicating sFRP4’s capacity to segregate the tumor spheres and allow chemotherapeutic drugs to inhibit tumor proliferation. This was further confirmed by immunofluorescence, where spheroids were labelled with CD44+/CD24−/low/ABCG2/KI67 for CSCs derived from breast tumors (Fig. 2a and b), and CD133+/CD44+/ABCG2/Ki67 for prostate (Fig. 2c and d) and ovarian tumors (Fig. 2e, f, and g); except for the prostate LnCap CSCs, which were not CD44+ (Fig. 2d). The combinatorial treatment showed sphere disruption and a reduction in surface receptor expression compared to sFRP4 and drugs alone, indicating the effect of sFRP4 in inhibiting the spheroids’ proliferative capacity.

Figure 1.

Effect of sFRP4 on CSC Morphology: CSCs were isolated from breast, ovary, and prostate tumor cell lines and treated with sFRP4 (250 pg) with chemotherapeutic drugs (doxorubicin 5 μM/cisplatin 30 μM). The combinatorial treatment shows the disruption of the CSC sphere. (Scale bar: 100 μm). Cells images are representative from all the experiments.

Figure 2.

Effect of sFRP4 on CSC cell surface markers: Using Immunofluorescence, CD44+/CD24−/CD133+/Ki67/ABCG2 were detected in all the tumor cell line-derived CSCs. sFRP4 in combination with doxorubicin/cisplatin showed disruption of the spheres. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). (a,b) CD44+/CD24− breast tumor cell line CSCs (MDA231/MCF7). (c,d) Prostate tumor cell line derived CSCs. PC3 expressed CD44+/CD133+/Ki67/ABCG2. LnCap was negative for CD44+. (e–g) CD44+/CD133+/Ki67/ABCG2 observed in ovary tumor cell line-derived CSCs (A2780 P/CIS/ADR). Immunofluorescence images are representative from 3 independent experiments. (Scale bar: 100 μm).

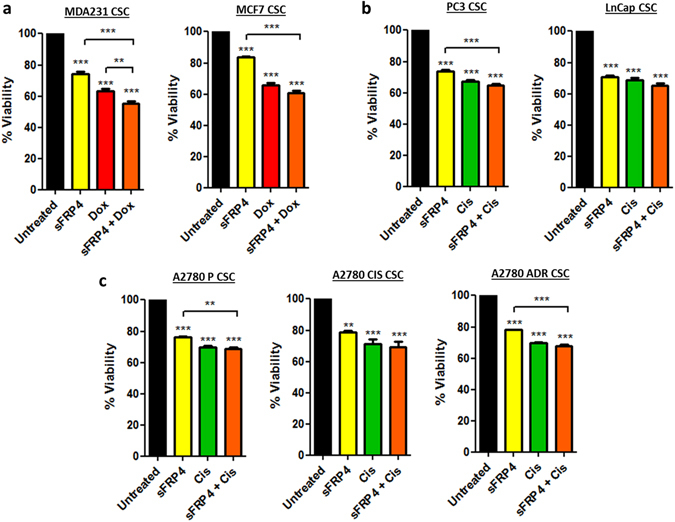

SFRP4 in combination with doxorubicin/cisplatin reduces CSC viability

Using an MTT assay, it was observed that the combinatorial treatment of sFRP4 and doxorubicin/cisplatin significantly inhibits the viability of CSCs (P < 0.001, n = 3) compared to sFRP4 or drugs alone. Similar patterns were observed in all the cell lines (Fig. 3). Therefore, this treatment combination was used for subsequent studies.

Figure 3.

Effect of sFRP4 on CSC viability: Viability assay was performed by MTT after treatment of CSCs derived from (a) Breast tumor cell line-derived CSCs (MDA231/MCF7). (b) Prostate tumor cell line-derived CSCs (PC3/LnCap). (c) Ovary tumor cell line-derived CSCs (A2780 P/CIS/ADR) with sFRP4 alone or in combination with doxorubicin/cisplatin for 24 hr. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA for analysis variance with Bonferroni test for comparison showing significance as ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± standard error of mean from 3 independent experiments.

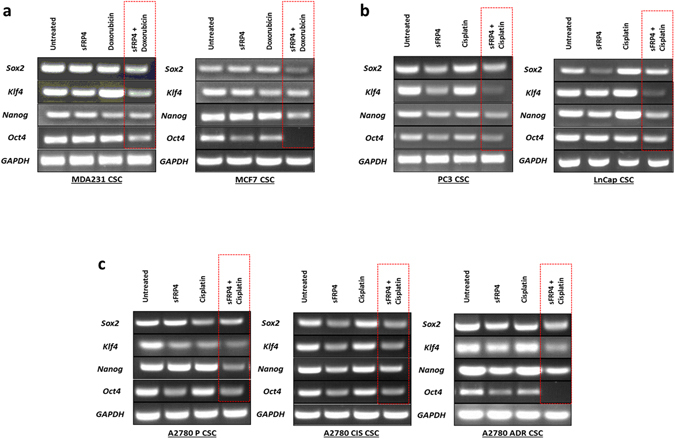

SFRP4 and doxorubicin/cisplatin treatment downregulates the expression of CSC stemness genes

The stemness related genes SOX2, Klf4, Nanog, and Oct4 are expressed in CSCs and are associated with tumor progression. Semi-quantitative PCR analysis showed the untreated CSCs expressing all the genes, but the treatment with sFRP4 alone or in combination with doxorubicin/cisplatin downregulated the expression of SOX2, Klf4, Nanog, and Oct4 in all the cell line-derived CSCs. The combinatorial treatment showed maximum reduction of gene expression, indicating that sFRP4 in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs has the capacity to reverse the stem cell-like properties of CSCs (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of sFRP4 on CSC stemness gene expression: sFRP4 in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs (Dox/Cis.) reduced the expression of stemness-related genes, indicating loss of stem like expression and differentiation capacity. Semi-quantitative PCR images are representative of 3 experiments.

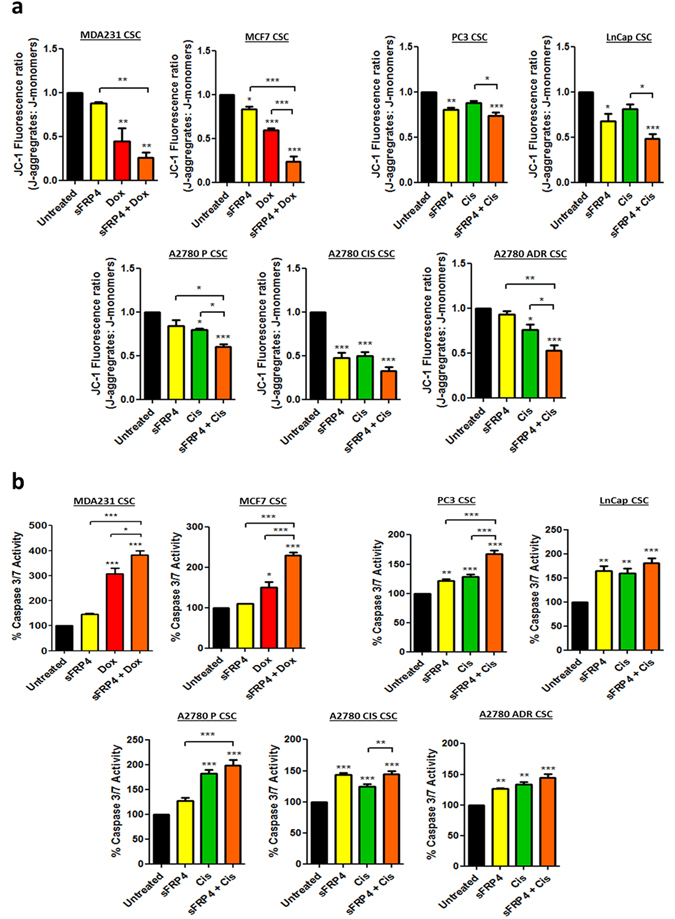

SFRP4 mediates early apoptotic events in CSCs

The disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential was investigated by using JC-1 dye. Results from the JC-1 assay demonstrated a significant increase (p < 0.01) in mitochondrial depolarization after treatment with sFRP4, doxorubicin/cisplatin alone, and in combinatorial treatments compared to untreated control. In all cell line-derived CSCs, maximum depolarization was observed in combinatorial treatments, indicating early stage death and apoptotic response through sFRP4 (Fig. 5a). To further confirm the apoptotic role of sFRP4 in CSCs, we studied caspase 3 activity in CSCs derived from all cell lines, which indicated increased caspase 3 activity (p < 0.001) in the sFRP4 alone and combinatorial treatments in comparison to untreated cells (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

sFRP4 initiates early apoptotic events in CSCs. (a) Detection of JC-1: The JC-1 assay demonstrated a high mitochondrial depolarization in sFRP4, doxorubicin/cisplatin, and combination-treated CSCs, indicating early stage cell death and apoptotic response to the various drug treatments. The combinatorial treatment on CSCs showed maximum depolarization. (b) Detection of caspase-3 activity: Increasing amount of caspase-3 substrate indicates initiation of apoptosis. The caspase-3 activity (an indicator of late apoptosis) of CSCs was significantly upregulated in combinatorial treatment compared to untreated cells. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA for analysis variance with Bonferroni test for comparison showing significance as ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. Data are mean ± standard error of mean from 4 independent experiments.

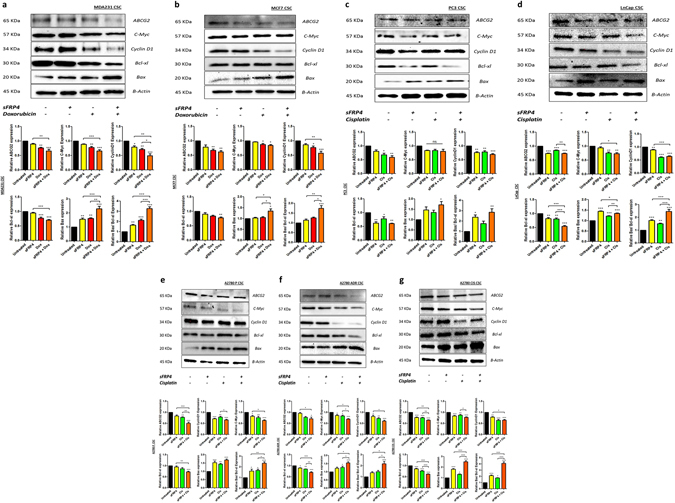

SFRP4 regulates protein expression in CSCs

Following sFRP4 treatment, we investigated the post-translational modifications in CSCs for ABC transporters (ABCG2), oncogenes (c-Myc), anchorage independent cell survival (Cyclin D1), anti-apoptotic (Bcl-xl), and pro-apoptotic (Bax) proteins. Results demonstrated the existing chemo-resistance of CSCs (Fig. 6). ABCG2 was highly expressed in the untreated groups but decreased in the presence of sFRP4, doxorubicin/cisplatin, and combinatorial treatments, with the latter inducing the lowest expression levels. c-Myc had similar expression levels in all CSCs, except ovarian A2780-Cis CSCs (Fig. 6g). The levels of the proto-oncogene cyclin D1 decreased in all the combinatorial treatments of CSCs compared to untreated CSCs, except in prostate PC3 CSCs (Fig. 6c). Overexpression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xl in untreated CSCs confers chemo-resistance; however, the combinatorial treatment produced a significant decrease in protein expression levels, indicating sFRP4’s pro-apoptotic capacity. Expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax was lower in untreated CSCs but increased significantly with combinatorial treatment. The increased Bax/Bcl-xl expression level ratio confirms the pro-apoptotic role of sFRP4.

Figure 6.

Effects of sFRP4 on protein expression levels: The combinatorial treatment of sFRP4 and chemotherapeutic drugs significantly upregulated the apoptotic protein (Bax) and downregulated cell survival (Cyclin D1) and oncogenes (C-Myc). (a,b) Breast tumor cell line-derived CSCs (MDA231/MCF7). (c,d) Prostate tumor cell line-derived CSCs (PC3/LnCap). (e–g) Ovary tumor cell line-derived CSCs (A2780 P/CIS/ADR). In combinatorial treatment, an elevated Bax/Bcl-xl ratio corresponded to elevated cell apoptosis. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA for analysis variance with Bonferroni test for comparison showing significance as ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. Blots and relative protein expressions are mean ± standard error of mean from 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

The role of CSCs in solid tumors is well established20–22. CSCs are in a quiescent state and remain in the resting phase of the cell cycle (G0 phase), expressing high levels of drug efflux transport systems23, 24. Due to the CSCs’ dormant state, chemotherapeutic drugs are unable to target CSCs, whereas they kill only proliferative tumor cells that are in M phase25, 26. Therefore, the knowledge of chemo-resistance associated with CSCs is of great importance for our understanding of tumors of the reproductive system (i.e. breast, prostate, and ovary), which are tumors with poor prognosis. In order to gain further insights into the chemo-sensitization of CSCs, we investigated the role of sFRP4 when used in combination with the chemotherapeutic drugs doxorubicin and cisplatin on CSCs derived from various tumor cell lines. Our study demonstrates sFRP4 alone or in combinatorial treatment with chemotherapeutic drugs elicits anti-proliferative effects, spheroid disruption, decrease in cell survival, and initiation of apoptosis within the CSCs, therefore indicating chemo-sensitization.

The CSCs were identified from breast (MDA231 and MCF7), prostate (PC3 and LnCap), and ovary (A2780 P, A2780 ADR, and A2780 CIS) tumor cell lines based on their ability to form spheroids in serum free conditions, elevated expression of CSC surface markers, high expression of ABC drug transporters (ABCG2), cell survival protein (Cyclin D1), oncogenes (c-Myc), and the ability to escape cell death/apoptosis (Bcl-xl). The resistance in CSCs is often correlated to the CSC surface marker profiles; CD44+High and CD133+High cells are highly radio-resistant in colon cancer and they have a higher DNA repair capacity and ability to escape apoptosis compared to CD44Low and CD133Low CSCs27. Targeting CD44+ cells demonstrated higher anti-proliferative activity in-vitro compared to the anti-tumor drug SN38 when used against colon, gastric, breast, esophageal, lung, and ovarian cancer cells28, 29. A reduction in the expression of CSC markers was observed in our study, where we demonstrated that sFRP4 in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs was able to decrease the CD44+ / 24− population for breast-derived CSCs, and the CD44+ / CD133+ population for prostate and ovary-derived CSCs. In ovarian A2780 P derived CSCs, the cisplatin treatment aberrantly increased the CD133+ CD44+ population, and decreased the CD44+ and CD133+ alone population; this aberration could imply that phenotypic switching of CSCs has occurred, a process that is still not well understood30.

Clinically, CSCs reside in anatomically distinct regions within the tumor microenvironment (known as niches), which preserve the CSCs’ phenotypic plasticity, facilitate metastatic potential, and support high expression of drug efflux transporters, making them highly chemo-resistant31. Although CSC isolation and characterization has been studied extensively, in-vitro CSCs niches are characterized by spheroid forming capacity in serum free conditions32. We showed that targeting the Wnt signaling pathway by using sFRP4 has the capacity to disrupt the niches when sFRP4 was used in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs. Spheroid disruption by sFRP4 decreases the CSCs’ plasticity and cell-cell adhesion, initiating the CSCs’ differentiation towards tumor cells and reducing their self-renewal capacity. This opens the gateway for chemotherapeutic drugs to target the cells at high potency. We confirmed spheroid disruption using immunofluorescence, and we observed the spheroid disruption was associated with a reduced CSCs’ marker profile. We also observed a marked reduction of the proliferation marker Ki-67 and drug transporter ABCG2 in sFRP4 combinatorial treatment. The prostate cell line LnCap-derived CSCs showed an absence of CD44+ expression, which is in agreement with previous work33.

In previous studies, sFRP4 has shown an anti-proliferative capacity in CSCs derived from glioblastoma multiforme, and head and neck tumor19, 34. In this study we have demonstrated that sFRP4 in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs decreased the viability of CSCs compared to drug treatment alone, indicating sFRP4’s role in the increased chemo-response of CSCs.

The Wnt signaling pathway has been reported to regulate stemness in CSCs derived from colon cancer35 and breast cancer36, although Wnt activation is higher in breast CSCs compared to normal stem-like cells37. Genes controlling the stemness of CSCs have distinct functions and are important for CSC development and self-renewal, and are responsible for replicative quiescence38. We hypothesized that cancer stemness inhibition can effectively suppress metastatic potential and tumor recurrence, although gene profiling of cancer stemness is more similar to embryonic stem cells than adult stem cells39. In this study, we show that sFRP4 reduced the expression of various stemness genes including Sox2, Klf4, Nanog, and Oct4 when treated in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs. These genes encode key stemness transcription factors that are important for maintenance of pluripotency40, 41. These data demonstrate the role of sFRP4 in inhibiting CSCs by modulating stemness gene expression.

Chemo-resistance of CSCs is due to alterations in expression of anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2 family) and pro-apoptotic (Bax) genes42. Apoptosis can be triggered by two pathways: (a) the extrinsic pathway where caspase-8 activation is initiated by the ligand of death receptors on the cell surface; and (b) the intrinsic pathway where mitochondria release cytochrome c 43. Release of cytochrome c is a crucial step that activates caspase-9 by assembling the apoptosome, further activating the downstream executioners caspase 3/744. In previous studies, the relationship between sFRP4 and apoptosis has been identified, demonstrating sFRP4 as a pro-apoptotic agent18, 45. This was further confirmed by assessing the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane when the CSCs were treated with sFRP4. We observed the mitochondrial depolarization by application of the JC-1 assay, as low ∆ψM (mitochondrial membrane potential) due to depolarization is indicative of apoptosis, indicating sFRP4 chemo-sensitzation involves the initiation of apoptotic pathways. We further demonstrated the pro-apoptotic role of sFRP4 with an elevation in caspase 3/7 expression in CSCs treated with sFRP4 alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs, indicating the later onset of apoptosis.

The overexpression of Bcl-2 is associated with chemo-resistance. The 3D protein structure of Bcl-xl revealed the structural similarities within the Bcl-2 family, possessing 4 BH domains and promoting cell survival by inactivation of Bcl-2 counterparts and preserving outer mitochondrial membrane integrity46. One of the early studies to show the chemo-sensitizing effects targeting Bcl-2 involved treating patients with Bcl-2 antisense (oblimersen sodium) in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, leading to improved survival47, 48. We hypothesized that sFPR4 has the potential to bind the hydrophobic groove of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, which would oligomerize Bax and can subsequently lead to mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization, releasing cytochrome c. We demonstrated a gradual increase in Bax expression and decreased Bcl-xl expression with sFRP4 and chemotherapeutic drug treatment alone; however, the combinatorial treatment elevated Bax and inversed the effect on Bcl-xl. The Bax/Bcl-xl ratio is an indicator for apoptosis, and an increased ratio depicts the activation of caspase 349. The Bax/Bcl-xl ratio was consistently high in all CSCs treated with combinatorial treatment. The elevated expression of apoptotic genes within all the CSCs indicates sFRP4’s role as a pro-apoptotic agent.

We also observed a decrease in Cyclin D1 expression, which is an oncogene driving cell cycle progression. Cyclin D1 interacts with proteins involved with DNA repair, RNA metabolism, and cell structure; deregulation of Cyclin D1 will affect cellular processes and eventually lead to an inefficient DNA damage repair system50. In the Wnt signaling pathway, GSK-3β regulates Cyclin D1 degradation, and the gene expression is activated by Wnt signaling51, 52. SFRP4 is a Wnt antagonist, which binds to the frizzled receptors and activates the GSK-3β destruction complex, initiating the degradation of Cyclin D1. In contrast, c-Myc expression showed no decrease in A2780 CIS, PC3, and MCF7-derived CSCs. c-Myc is an oncoprotein that is an important regulator in stem cell biology53 and correlates to tumor metastasis39. CSCs exhibit a high expression of c-Myc, and downregulation of c-Myc leads to apoptosis under various circumstances54–57. We hypothesize that a different dose of sFRP4 and chemotherapeutic drugs would enable a reduction in c-Myc expression.

In summary, sFRP4 chemo-sensitizes CSCs derived from breast, prostate, and ovary tumor cell lines by reducing their pro-oncogenic profile, stemness capacity, cell survival protein and oncogene expression, making them more responsive to chemotherapeutic drugs. Chemo-sensitization by sFRP4 in vivo may decrease the required chemotherapeutic load required to reduce the tumor mass. SFRP4 prevents a sustained Wnt inhibition in order to provide a therapeutic window for chemotherapy while sparing normal Wnt-dependent tissues. Further in vivo studies may confirm the role of sFRP4 in the chemo-sensitization of CSCs to prevent tumor relapse and lead to tumor resolution.

Materials and Methods

Monolayer cell culture

Cell culture plates for adherent cells were purchased from Nunc™ (ThermoFisher Scientific). The human breast cells line MDA-MB 231 (ER-) and MCF-7 (ER+), human ovary cell lines A2780-P, A2780-ADR, and A2780-Cis, and human prostate cell lines PC-3 (AR−/PSA−) and LnCap (AR+) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco #11875–093) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Bovogen #SFBS) and 100 U/ml PenStrep (Life Technologies #15070063). All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humid incubator with 5% CO2.

Cancer stem cell isolation

For CSC isolation, culture plates with an ultra-low-attachment surface were purchased from Corning Life Sciences. CSCs were cultured in serum-free medium (SFM) containing basal medium RPMI-1640 + DMEM-HG (HyClone, USA #SH30081.02) supplemented with the growth factors bFGF (20 ng/ml) (ProSpec Bio #cyt-085), EGF (20 ng/ml) (ProSpec Bio #cyt-217), and 1× B27 (Gibco #17504044), and 100 U/ml PenStrep (Life Technologies #15070063). CSC-enriched populations of cells were obtained by plating a single cell suspension of breast, ovary, and prostate tumor cells at 10000 cells/cm² in SFM on Low-adherent six-well plates (Corning #3471). CSCs were isolated in SFM; the spheroids are formed at 3rd Day of plating tumour cells. SFRP4 (250 pg) and chemotherapeutic drugs alone or in combination were added on the 3rd Day for 24 hours. Post 24 hour treatment; the spheroids were dissociated and maintained in CSC culture medium in low-attachment-surface plates for functional studies.

Chemo-Sensitization/Drug treatment

The drugs used in this study were purified sFRP4 (R&D Systems #1827-SF-025), doxorubicin (Sigma #D1515), and cisplatin (Sigma #P4394). CSC sensitization with sFRP4 was performed by adding sFRP4 to the cell culture at 250 pg/ml58 for 24 hr at 37 °C in 5% CO2 incubator. Doxorubicin was tested at an IC50 value of 1–10 μM. Cisplatin was tested at its IC50 value of 10–50 μM. The drug treatment for the downstream analysis was optimized at 250 pg of sFRP4 alone or in combination with 5 μM of doxorubicin (breast tumor cells only) and 30 μM of cisplatin (ovary and prostate tumor cells only) for 24 hr. An MTT assay was used for the analysis of cellular viability.

Cell Surface Markers

To assist in determining their identity, cell surface markers (Table 2) were examined in both monolayers and CSCs by flow cytometry (BD FACSCANTO II) using CellQuest data acquisition and analysis software. APC-CD44 (1:100) (BioLegend #338805), PE Cy7-CD24 (1:10) (BioLegend #311119), and PE-CD133 (1:100) (BioLegend #372803). Cells incubated with conjugated irrelevant IgGs were used as negative controls.

Table 2.

Tumor specific cancer stem cell markers.

Immunofluorescence staining

The spheroids were plated on Poly-D-lysine pre-coated 96 well plates (Sigma #6407), incubated at 37 °C for 3 hr, and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma #P6148) overnight at 4 °C. The cells were washed three times with PBS, incubated for 1 hr in 1% BSA Blocking buffer, and incubated with primary antibodies CD44 (Cell Signaling #3570); CD24 (ThermoFisher #MA5-11828); CD133/1 (Miltenyi #130-090-422); ABCG2 (Cell Signaling #42078); Ki-67 (Millipore #AB9260) overnight at 4 °C. After three 10 mins washes with PBS, the cells were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (see Supplementary Table 1) for 1 hr at room temperature. After three 10 min PBS washes, cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma #14533) at 1:20000 dilution at room temperature for 15 min. The cells were then washed with PBS three times for 5 min each and observed using an Ultraview Vox spinning disk confocal microscope (Perkin Elmer).

MTT Viability Assay

Cell viability kit

An MTT kit (Sigma #M5655) was used to measure cell metabolic viability.

Monolayers

5000 cells/cm² were plated in a flat-bottomed 96-well plate for 2 days with culture medium. After that, sFRP4 alone or in combination with the tumor-specific drug was added and the cells were incubated for 24 hr. After drug treatment, the MTT assay was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

CSCs

10000 cells/cm² of monolayer cells were plated in a low-adherent flat-bottomed 96-well plate (Corning #3474) for 3 days in non-adherent SFM conditions. After that, sFRP4 alone or in combination with the tumor-specific drug treatment was added and the cells left for 24 hr, following which the MTT assay was performed. Plates were read at 595 nm using an EnSpire Multilabel Plate Reader (Perkin-Elmer).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies #15596026) followed by chloroform extraction, isopropanol precipitation, and a 75% (v/v) ethanol wash. RNA samples (1 μg) were reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a High Capacity cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems #4368814). cDNA in 1 μl of the reaction mixture was amplified with PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies #K0171) and 10 μmol each of the sense and antisense primers. The thermal cycle profile was as follows: denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55–61 °C for 30 s depending on the primers used, and extension at 72 °C for 90 s. Each PCR reaction was carried out for 35 cycles, and the PCR products were size fractionated on 1% agarose gel/GelGreen (1:10000) (Fisher Biotec #41005) and visualized under UV Trans illumination (FB Biotech). The primer sequences are described in Supplementary Table 2.

Western Blotting

Cells were washed twice with PBS and then lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Sigma #R0278) (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% IGEPAL® CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, Proteinase Inhibitor 1x). Post sonication, cell lysates were centrifuged at 14000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were used for Western blotting. The lysates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and then stained with 0.1% Ponceau S solution (Sigma #P3504) to ensure equal loading of the samples. After being blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 60 min, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies ABCG2 (Cell Signaling #42078); c-Myc (Cell Signaling #5605); Cyclin D1 (Abcam #ab134175); Bcl-xL (Cell Signaling #2764); Bax (Cell Signaling #5023); β-Actin (Cell Signaling #4970) overnight, and the bound antibodies were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies using the ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Amersham, GE #RPN2106) on a Chemi-Doc (Bio-Rad) imaging analyzer. The Primary antibodies concentrations are described in Supplementary Table 3.

Apoptosis Assays

JC-1 Assay

∆ψM is an important parameter of mitochondrial membrane and has been used as an indicator of cell health. JC-1 enters the mitochondria and changes its fluorescent properties based on aggregation of the probe, and forms complexes known as J-aggregates with intense red fluorescence. High ∆ψM predicts healthy cells and low ∆ψM exhibits mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization indicative of apoptosis. JC-1 activity was measured using JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit (Cayman #10009172). CSCs were enriched in 96 well low attachment plates, and treated with sFRP4 alone and in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs for 24 hr and compared with untreated CSCs. Post-treatment, 10 μl of JC-1 staining solution was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The plate was washed with assay buffer at 400 g for 5 min twice. This was followed by addition of 100 μl of assay buffer to each well and read using an EnSpire Multilabel Plate Reader (Perkin-Elmer) for analysis. JC-1 aggregates were measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 535 nm and 595 nm respectively. JC-1 monomers were measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 535 nm. The ratio of fluorescent intensity of J-aggregates and J-monomers (Red: Green) was used as an indicator of cell health. The JC-1 assay kit is highly light sensitive and all procedures were conducted in dark conditions.

Caspase-3 Assay

Caspase-3 activity was measured using the EnzChek Caspase-3 Assay Kit II (Molecular Probes #E13184). Briefly, 50 μl of the supernatant was added to an individual well of a 96-well micro fluorescent plate and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. After incubation, 50 μl of the 2× working substrate (5 M Z-DEVD-R110) were added to each well and further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Fluorescence was measured at 485 nm excitation and 538 nm emissions using an EnSpire Multilabel Plate Reader (Perkin-Elmer). Caspase-3 activity was expressed as arbitrary units of fluorescence.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism V5.0 (GraphPad software, La Jolla, USA) using one-way ANOVA for analysis variance with Bonferroni test for comparison showing significance as ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of mean.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Abhijeet Deshmukh is supported by a scholarship from the Office of Research & Development, the School of Biomedical Sciences and Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University. The authors additionally thank the School of Biomedical Sciences, Curtin University for research and postgraduate student support. Thanks to Prof. Peter Leedman, (Harry Perkins institute of Medical research, Perth, Australia) for providing PC3 and LnCap cell lines.

Author Contributions

Abhi D. drafted the outline and generated the data. S.K. contributed the viability data. Abhi D. wrote the manuscript. Abhi D. and Arun D. conceived the study, and Arun D., F.A., and P.N. critically reviewed, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-02256-4

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel R, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh SK, et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tu LC, Foltz G, Lin E, Hood L, Tian Q. Targeting stem cells-clinical implications for cancer therapy. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2009;4:147–153. doi: 10.2174/157488809788167373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yuan S, et al. Effective elimination of cancer stem cells by a novel drug combination strategy. Stem Cells. 2013;31:23–34. doi: 10.1002/stem.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Dhfyan A, Alhoshani A, Korashy HM. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor/cytochrome P450 1A1 pathway mediates breast cancer stem cells expansion through PTEN inhibition and beta-Catenin and Akt activation. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:14. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdullah LN, Chow EK. Mechanisms of chemoresistance in cancer stem cells. Clin Transl Med. 2013;2:3. doi: 10.1186/2001-1326-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bomken S, Fiser K, Heidenreich O, Vormoor J. Understanding the cancer stem cell. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:439–445. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patrawala L, et al. Side population is enriched in tumorigenic, stem-like cancer cells, whereas ABCG2+ and ABCG2- cancer cells are similarly tumorigenic. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6207–6219. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patrawala L, et al. Highly purified CD44+ prostate cancer cells from xenograft human tumors are enriched in tumorigenic and metastatic progenitor cells. Oncogene. 2006;25:1696–1708. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin J, et al. The PSA(−/lo) prostate cancer cell population harbors self-renewing long-term tumor-propagating cells that resist castration. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medema JP. Cancer stem cells: the challenges ahead. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:338–344. doi: 10.1038/ncb2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang DG. Understanding cancer stem cell heterogeneity and plasticity. Cell Res. 2012;22:457–472. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malanchi I, et al. Cutaneous cancer stem cell maintenance is dependent on beta-catenin signalling. Nature. 2008;452:650–653. doi: 10.1038/nature06835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He X, Semenov M, Tamai K, Zeng X. LDL receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 in Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: arrows point the way. Development. 2004;131:1663–1677. doi: 10.1242/dev.01117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saran U, Arfuso F, Zeps N, Dharmarajan A. Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 expression is positively associated with responsiveness to cisplatin of ovarian cancer cell lines in vitro and with lower tumour grade in mucinous ovarian cancers. BMC Cell Biol. 2012;13:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-13-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warrier S, Balu SK, Kumar AP, Millward M, Dharmarajan A. Wnt antagonist, secreted frizzled-related protein 4 (sFRP4), increases chemotherapeutic response of glioma stem-like cells. Oncol Res. 2013;21:93–102. doi: 10.3727/096504013X13786659070154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardal R, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ. Applying the principles of stem-cell biology to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:895–902. doi: 10.1038/nrc1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanai N, Alvarez-Buylla A, Berger MS. Neural stem cells and the origin of gliomas. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:811–822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheong HT, Park TM, Ikeda K, Takahashi Y. Cell cycle analysis of bovine cultured somatic cells by flow cytometry. Jpn J Vet Res. 2003;51:95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung TH, Rando TA. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrm3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schatton T, et al. Identification of cells initiating human melanomas. Nature. 2008;451:345–349. doi: 10.1038/nature06489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams JM, Strasser A. Is tumor growth sustained by rare cancer stem cells or dominant clones? Cancer Res. 2008;68:4018–4021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahlberg SH, Spiegelberg D, Glimelius B, Stenerlow B, Nestor M. Evaluation of cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44, CD24: association with AKT isoforms and radiation resistance in colon cancer cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serafino A, et al. CD44-targeting for antitumor drug delivery: a new SN-38-hyaluronan bioconjugate for locoregional treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2011;11:572–585. doi: 10.2174/156800911795655976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattheolabakis G, Milane L, Singh A, Amiji MM. Hyaluronic acid targeting of CD44 for cancer therapy: from receptor biology to nanomedicine. J Drug Target. 2015;23:605–618. doi: 10.3109/1061186X.2015.1052072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zapperi S, La Porta CA. Do cancer cells undergo phenotypic switching? The case for imperfect cancer stem cell markers. Sci Rep. 2012;2:441. doi: 10.1038/srep00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lobo NA, Shimono Y, Qian D, Clarke MF. The biology of cancer stem cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:675–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verkaik NS, Trapman J, Romijn JC, Van der Kwast TH, Van Steenbrugge GJ. Down-regulation of CD44 expression in human prostatic carcinoma cell lines is correlated with DNA hypermethylation. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:439–443. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990129)80:3<439::AID-IJC17>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warrier S, et al. Cancer stem-like cells from head and neck cancers are chemosensitized by the Wnt antagonist, sFRP4, by inducing apoptosis, decreasing stemness, drug resistance and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cancer Gene Ther. 2014;21:381–388. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2014.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaler P, Godasi BN, Augenlicht L, Klampfer L. The NF-kappaB/AKT-dependent Induction of Wnt Signaling in Colon Cancer Cells by Macrophages and IL-1beta. Cancer Microenviron. 2009;2:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s12307-009-0030-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lamb R, et al. Wnt pathway activity in breast cancer sub-types and stem-like cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klopocki E, et al. Loss of SFRP1 is associated with breast cancer progression and poor prognosis in early stage tumors. Int J Oncol. 2004;25:641–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicolis SK. Cancer stem cells and “stemness” genes in neuro-oncology. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;25:217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong DJ, et al. Module map of stem cell genes guides creation of epithelial cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizzino A. Concise review: The Sox2-Oct4 connection: critical players in a much larger interdependent network integrated at multiple levels. Stem Cells. 2013;31:1033–1039. doi: 10.1002/stem.1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saunders A, Faiola F, Wang J. Concise review: pursuing self-renewal and pluripotency with the stem cell factor Nanog. Stem Cells. 2013;31:1227–1236. doi: 10.1002/stem.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Todaro M, et al. Colon cancer stem cells dictate tumor growth and resist cell death by production of interleukin-4. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Bruin EC, Medema JP. Apoptosis and non-apoptotic deaths in cancer development and treatment response. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agarwal R, Kaye SB. Ovarian cancer: strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:502–516. doi: 10.1038/nrc1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muchmore SW, et al. X-ray and NMR structure of human Bcl-xL, an inhibitor of programmed cell death. Nature. 1996;381:335–341. doi: 10.1038/381335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rai, K. R. The natural history of CLL and new prognostic markers. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol6, 4–5, quiz 10–12 (2008). [PubMed]

- 49.Salakou S, et al. Increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio up-regulates caspase-3 and increases apoptosis in the thymus of patients with myasthenia gravis. In Vivo. 2007;21:123–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jirawatnotai S, et al. A function for cyclin D1 in DNA repair uncovered by protein interactome analyses in human cancers. Nature. 2011;474:230–234. doi: 10.1038/nature10155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen P, Frame S. The renaissance of GSK3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:769–776. doi: 10.1038/35096075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takahashi-Yanaga F, Sasaguri T. GSK-3beta regulates cyclin D1 expression: a new target for chemotherapy. Cell Signal. 2008;20:581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy MJ, Wilson A, Trumpp A. More than just proliferation: Myc function in stem cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaptein JS, et al. Anti-IgM-mediated regulation of c-myc and its possible relationship to apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18875–18884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson EB. The many roles of c-Myc in apoptosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:575–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang MJ, Cheng YC, Liu CR, Lin S, Liu HE. A small-molecule c-Myc inhibitor, 10058-F4, induces cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and myeloid differentiation of human acute myeloid leukemia. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1480–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prendergast GC. Mechanisms of apoptosis by c-Myc. Oncogene. 1999;18:2967–2987. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhuvanalakshmi G, Arfuso F, Millward M, Dharmarajan A, Warrier S. Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 inhibits glioma stem-like cells by reversing epithelial to mesenchymal transition, inducing apoptosis and decreasing cancer stem cell properties. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 59.Karsten U, Goletz S. What makes cancer stem cell markers different? Springerplus. 2013;2:301. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim DK, et al. Crucial role of HMGA1 in the self-renewal and drug resistance of ovarian cancer stem cells. Exp Mol Med. 2016;48:e255. doi: 10.1038/emm.2016.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collins AT, Berry PA, Hyde C, Stower MJ, Maitland NJ. Prospective identification of tumorigenic prostate cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10946–10951. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.