Abstract

Efficient allelic exchange mutagenesis in group B streptococci (GBS) has been hampered by the lack of a counterselectable marker system. Growth inhibition of GBS by the glutamine analog gamma-glutamyl hydrazide requires glnQ. We have used this phenomenon to create a counterselectable marker system for efficient selection of allelic exchange mutants in GBS.

Group B streptococci (GBS) are the leading cause of meningitis and sepsis in newborns in the United States and Western Europe (1). Recent advances have allowed for genetic manipulation of GBS, including the use of temperature-sensitive (TS) vectors for creation of allelic exchange mutations (17). However, creation of allelic exchange mutations in GBS is a laborious process that sometimes requires replica plating several thousand individual colonies (H. H. Yim, unpublished data). Creation of such mutations has been hampered by the lack of a counterselectable marker system for use with GBS.

We have recently discovered that wild-type GBS do not grow in the presence of the glutamine analog gamma-glutamyl hydrazide (GGH) and that this inhibition requires the glutamine transport gene glnQ (14). This finding led us to hypothesize that glnQ, when expressed on a plasmid in the background of a parent strain with a deletion in glnQ, could be used as a counterselectable marker. We now report that we have developed a counterselectable marker by using glnQ with GGH selection and have used this system to isolate mutant GBS strains that have the chromosomal capsular polysaccharide regulatory gene cpsB replaced by the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene.

Selection against glnQ-expressing GBS by GGH is robust

We previously isolated COH1-GT1, a Tn917 transposon mutant derivative of a virulent GBS strain (COH1). COH1-GT1 is deficient in glutamine transport due to a Tn917 insertion in glnQ, a homologue of a gene from Escherichia coli that is required for high-affinity, energy-dependent glutamine transport (14). We previously demonstrated that COH1-GT1 was resistant to GGH at 100 μg/ml when grown in a minimal medium containing M9 salts, 1% glucose, and 0.1% yeast extract (M9GYE), whereas the growth of COH1 was completely inhibited. We have subsequently demonstrated similar findings with inocula as high as 105 CFU/plate (data not shown). These results demonstrate that the glnQ-mediated sensitivity to GGH is sufficiently robust to allow for use of glnQ as a counterselectable marker.

Expression of glnQ in trans confers sensitivity to GGH in a glnQ mutant GBS strain

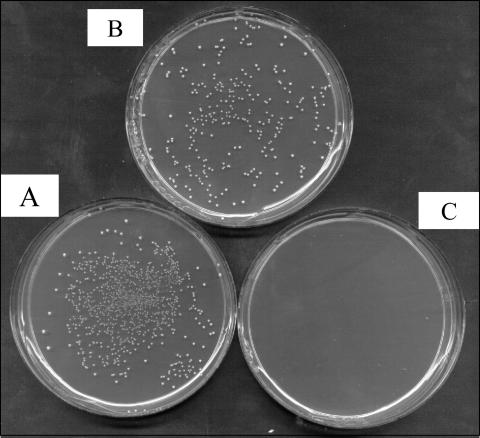

We hypothesized that the glnQ gene expressed on a plasmid could be used as a counterselectable marker when used in the background of a host lacking the glnQ gene, such as COH1-GT1. To test this hypothesis, we used pAG200, a complementation plasmid we had previously constructed which contains the glnQ gene expressed in the gram-positive shuttle vector pDC123. pAG200 is able to complement the glutamine transport defect of COH1-GT1 (14). We plated COH1-GT1 containing pAG200 onto M9GYE agar with 100 μg of GGH and 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml to maintain the presence of the plasmid. The results are shown in Fig. 1. We confirmed that COH1-GT1 is able to grow in the presence of GGH (Fig. 1A). COH1-GT1 with pAG200 was able to grow on medium containing chloramphenicol (Fig. 1B) but not on medium containing both chloramphenicol and GGH (Fig. 1C). These results demonstrated that pAG200 confers sensitivity to GGH in a ΔglnQ background and thus acts as a counterselectable marker.

FIG. 1.

pAG200 confers sensitivity to GGH in the background of COH1-GT1. (A) COH1-GT1, with GGH; (B) COH1-GT1:pAG200, with chloramphenicol; (C) COH1-GT1:pAG200, with chloramphenicol and GGH.

Creation of derivatives of GBS strains COH31rs and A909 with mutations in glnQ

We then sought to create ΔglnQ host strains from laboratory strains of GBS with high transformation efficiencies. Because COH1 has a very low transformation efficiency (∼103 CFU/μg of DNA), much of the genetic manipulation of GBS has been performed on laboratory strains such as A909 and COH31rs that have much higher transformation efficiencies (∼105 CFU/μg of DNA). We therefore undertook to create derivatives of these laboratory strains with site-directed mutations in glnQ that could then be used as hosts for a glnQ counterselectable marker system. We created site-directed mutations in glnQ in A909 and COH31rs by using pAG101, a plasmid containing the glnQ gene with an 80-bp internal fragment replaced with an erythromycin resistance gene (erm) in a TS background as previously described (14). The presence of the mutations was confirmed by PCR as described earlier. One isolate for each host was designated A909-DLS1 and COH31-DLS1, respectively, and used as the GGH-resistant host in subsequent experiments.

Generation of cpsB allelic exchange mutants

We then tested the utility of glnQ as a counterselectable marker in the creation of allelic exchange mutations in GBS by using the cpsB gene as a test case. cpsB is the second gene in the capsular polysaccharide locus of GBS and appears to be involved in regulation of capsule expression (4). A previously described 3.0-kb EcoRI/EcoRV fragment from the capsule region of COH1 containing the cpsB, along with adjacent fragments of the cpsA and cpsC (2), was cloned into pHY304, a TS shuttle vector encoding erythromycin resistance, to create pHY306. An exact allelic replacement of the cpsB gene with the cat gene was then created by using an in vivo ligation. A DNA fragment containing the cpsA and cpsC gene fragments flanking cpsB, together with vector sequences, was created by PCR by using pHY306 as a template and outward-reading primers (Table 1, cpsA3′R and cpsC5′F) that were synthesized with a 5′ extension consisting of 20bp of the 5′ and 3′ ends of cat, respectively. The cat gene was amplified by using pDC123 as a template, and primers cat F and cat R (Table 1). Both PCR products were simultaneously electroporated into the E. coli strain MC1061 and transformants were selected on LA with 10 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. The integrity of one resulting clone was confirmed by limited restriction mapping, and designated pHY306.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Description or sequencea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| COH1 | Wild-type III GBS strain | 15 |

| COH1-GT1 | COH1, Tn917 glnQ/Emr | 14 |

| COH31rs | Wild-type III GBS strain | 12 |

| COH31rs-DLS1 | COH31rs, glnQ::erm | This study |

| COH31rs-DLS2 | COH31rs glnQ::erm cpsB::cat | This study |

| A909 | Wild-type Ia GBS strain | 5 |

| A909-DLS1 | A909, glnQ::erm | This study |

| A909-DLS2 | A909, glnQ::erm cpsB::cat | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVE6007 | Cmr temperature-sensitive shuttle vector; 3.4 kb; ori(Ts) | 8 |

| pCER1000 | Emr; erm cloned into pUC8 | 11 |

| pDC123 | CmrphoZ; blue-white screening shuttle expression vector | 3 |

| pAG101 | Cmr Emr; pVE6007 with partial 739-bp glnQ with an 80-bp deletion and an insertion of 868-bp erm from pCER1000 via HindIII ligation | 14 |

| pAG200 | Cmr; pDC123, cat glnQ | 14 |

| pHY304 | Emr; derivative of pVE6007, lacZα/multiple cloning site of pBluescript | 10 |

| pHY306 | Emr Cmr; pHY304 with cat flanked by 365 bp of cpsA and 573 bp of cpsC | This study |

| pDLS104 | Cmr Kmr Emr; kan from pCIV2 and glnQ from pAG200 cloned into pHY306 | This study |

| pCIV2 | Kmr/ΩKm-2 | 9 |

| Primers | ||

| kanF | ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCTAGATTTTAATGCG | |

| kanR | ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCATGGACGATACAAA | |

| cpsAF | ATGACGGTTAATACCAATACCCA | |

| cpsCR | CCTGCACCAACAATAAACCCGATTAG | |

| glnQF1 | GGCTTAATCGATGGCAGAATTAAAAATTGATGTCCA | |

| glnQR1 | AACTGAATTCAGGAAGTCTTGGAGACGTGGG | |

| glnQF2 | GTCAAATGGAAGCAAGTCGCA | |

| glnQR2 | CTGAAAGCCCTTGTGCAACATT | |

| glnPF | GTCAAATGGAAGCAAGTCGCA | |

| glnQ3′R | CTGAAAGCCCTTGTGCAACATT | |

| cpsBF | TCGACATCACATAGAAGAAAAGG | |

| cpsBR | ATGGCGGTCTAACATCAAGG | |

| catF | GACAAGCTTAGCAGACAAGTAAGCCTCCTA | |

| catR | GCAGCGCTCTCATATTATAAAAGCCAGTC | |

| cpsA3′R | CCTAATGACTGGCTTTTAGATTATCTGTAGAGATTTCGGTAA | |

| cpsC5′F | TCAATTTTATTAAAGTTCATAATTTTTGATTTTGCATTAGATA |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Emr, erythromycin resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant.

A kanamycin resistance cassette and the glnQ gene were then added to create pDLS104. The kan gene from pCIV2 was amplified with primers kanF and kanR containing NotI sites (Table 1), digested with NotI, and ligated into pBluescript II SK(+) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) to create pDLS101. The insert from pHY306 was released with EcoRV and EcoRI, and cloned into pDLS101 digested with EcoRI and HincII to create pDLS102. The glnQ gene from pAG200 was then cloned into pDLS102 by using XhoI and KpnI to create pDLS103. The entire insert from pDLS103 containing glnQ, kan, and the allelic exchange construct from pHY306 was cloned into pHY304 by using SacII and ClaI to create pDLS104.

To create allelic exchange mutations in cpsB, pDLS104 was transformed into COH31-DLS1 and A909-DLS1. Transformed strains were grown overnight in Todd-Hewitt broth with 500 μg of kanamycin/ml at 30°C, diluted 1:100, and grown overnight at 37°C in the absence of antibiotic selection to cure the plasmid. Approximately 106 CFU were then subjected to GGH selection in the presence of chloramphenicol on M9GYE. Individual colonies were then replica plated onto Todd-Hewitt broth with 10 μg of chloramphenicol and 500 μg of kanamycin/ml. A total of 31 of 42 (74%) of the COH31-DLS1 derivatives and 22 of 31 (71%) of the A909-DLS1 derivatives gave the expected antibiotic phenotype (chloramphenicol resistant, kanamycin sensitive), indicating that they had lost the plasmid kan marker but had retained the cat gene.

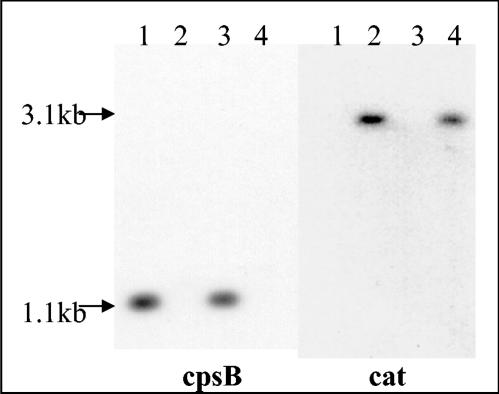

A single clone in each background was then designated COH31-DLS2 and A909-DLS2, respectively, and tested for the presence of the allelic exchange mutation by Southern blot analysis. The cat gene probe was created by PCR by using pDC123 DNA as a template and the catF and catR primers. The cpsB probe was created by PCR with genomic COH1 DNA as a template, and the cpsBF and cpsBR primers. Both probes were labeled with digoxigenin by using the DIG Chem-Link labeling and detection set (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, Ind.) with HindIII-digested chromosomal DNA from COH31-DLS2 and A909-DLS2 according to the manufacturer's protocol. The results are shown in Fig. 2. The cpsB region probe (left lanes) gave the expected 1.1-kb band for strains COH31rs (lane 1) and A909 (lane 3). No band hybridizing to the cpsB gene was seen for COH31-DLS2 (lane 2) or A909-DLS2 (lane 4), indicating that, as expected, the cpsB gene is not contained in these strains. A cat gene probe gave the expected 3.1-kb band for both COH31-DLS2 (lane 2) and A909-DLS2 (lane 4), confirming the presence of the expected allelic exchange mutation. Overall, these results demonstrate that an allelic exchange can be rapidly and efficiently performed in GBS with GGH as a counterselectable marker.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of cpsB and cat genes of allelic exchange mutants. Genomic GBS DNA was digested with HindIII, and Southern blot analysis was carried out as described with probes specific for cpsB (left lanes) and cat (right lanes). Lanes: 1, COH31rs DLS1; 2, COH31rs DLS2; 3, A909 DLS1; 4, A909 DLS2.

GGH counterselection could conceivably be used for a wide variety of organisms. In theory, GGH counterselection could be used with any organism that requires an intact glutamine transport gene for sensitivity to GGH. This phenomenon has been described for the glnQ gene of Bacillus stearothermophilus (16), Rhodobacter capsulatus (18), Rhodobacter sphaeroides (6), and the GNP1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (19).

In addition, glnQ homologues are found in wide variety of organisms, and the feasibility of GGH counterselection can be easily ascertained by comparing the sensitivity of wild-type and glnQ mutant strains to GGH. Testing for GGH sensitivity is generally done under nitrogen-limiting conditions that result in the induction of glutamine transport genes. Thus, one requirement for efficient GGH selection is the ability of the host organism to grow in nitrogen-poor minimal medium. Thus, GGH selection may not be applicable to bacteria that require complex media for growth.

A counterselectable marker system for gram-positive bacteria with rpsL has been described for S. pneumoniae. This system was used to create gene replacements without introduction of antibiotic resistance markers; we speculate that similar gene replacements could be introduced into GBS by using GGH counterselection.

One drawback of both the glnQ and rpsL systems is that both the glnQ mutations we describe (14) and rpsL mutations in other hosts (7, 13) can create fitness defects in vivo. Thus, mutants created by using these systems may not be optimal for use in some applications, such as virulence testing in vivo. Hydrazides of several amino acids have been used to demonstrate that particular genes are required for transport of particular amino acids. This suggests that other amino acid transport genes, together with their cognate amino acid hydrazides, could be used to create counterselectable marker systems. We speculate that such systems might not impose fitness constraints that complicate the interpretation of data from these mutants obtained by using animal models of infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Craig Rubens, Amanda Jones, and Anne Clancy for helpful suggestions.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R29 AI41484-01 to G.S.T.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baker, C. J. 1997. Group B streptococcal infections. Clin. Perinatol. 24:59-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaffin, D. O., S. B. Beres, H. H. Yim, and C. E. Rubens. 2000. The serotype of type Ia and III group B streptococci is determined by the polymerase gene within the polycistronic capsule operon. J. Bacteriol. 182:4466-4477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaffin, D. O., and C. E. Rubens. 1998. Blue/white screening of recombinant plasmids in gram-positive bacteria by interruption of alkaline phosphatase gene (phoZ) expression. Gene 219:91-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cieslewicz, M. J., D. L. Kasper, Y. Wang, and M. R. Wessels. 2001. Functional analysis in type Ia group B streptococcus of a cluster of genes involved in extracellular polysaccharide production by diverse species of streptococci. J. Biol. Chem. 276:139-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dochez, A. R., O. T. Avery, and R. C. Lancefield. 1938. Studies on the biology of streptococcus. I. Antigenic relationships between strains of Streptococcus haemolyticus. J. Exp. Med. 30:179-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs, M. H., T. van der Heide, B. Tolner, A. J. Driessen, and W. N. Konings. 1995. Expression of the gltP gene of Escherichia coli in a glutamate transport-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides restores chemotaxis to glutamate. Mol. Microbiol. 18:641-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeddeloh, J. A., D. L. Fritz, D. M. Waag, J. M. Hartings, and G. P. Andrews. 2003. Biodefense-driven murine model of pneumonic melioidosis. Infect. Immun. 71:584-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maguin, E., P. Duwat, T. Hege, D. Ehrlich, and A. Gruss. 1992. New thermosensitive plasmid for gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 174:5633-5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada, N., R. T. Geist, and M. G. Caparon. 1993. Positive transcriptional control of mry regulates virulence in the group A streptococcus. Mol. Microbiol. 7:893-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajagopal, L., A. Clancy, and C. E. Rubens. 2003. A eukaryotic type serine/threonine kinase and phosphatase in Streptococcus agalactiae reversibly phosphorylate an inorganic pyrophosphatase and affect growth, cell segregation, and virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14429-14441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubens, C. E., and L. M. Heggen. 1988. Tn916 delta E: a Tn916 transposon derivative expressing erythromycin resistance. Plasmid 20:137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubens, C. E., M. R. Wessels, L. M. Heggen, and D. L. Kasper. 1987. Transposon mutagenesis of type III group B streptococcus: correlation of capsule expression with virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:7208-7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung, C. K., H. Li, J. P. Claverys, and D. A. Morrison. 2001. An rpsL cassette, Janus, for gene replacement through negative selection in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5190-5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura, G. S., A. Nittayajarn, and D. L. Schoentag. 2002. A glutamine transport gene, glnQ, is required for fibronectin adherence and virulence of group B streptococci. Infect. Immun. 70:2877-2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wessels, M. R., R. F. Haft, L. M. Heggen, and C. E. Rubens. 1992. Identification of a genetic locus essential for capsule sialylation in type III group B streptococci. Infect. Immun. 60:392-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu, L., and N. E. Welker. 1991. Cloning and characterization of a glutamine transport operon of Bacillus stearothermophilus NUB36: effect of temperature on regulation of transcription. J. Bacteriol. 173:4877-4888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yim, H. H., A. Nittayarin, and C. E. Rubens. 1997. Analysis of the capsule synthesis locus, a virulence factor in group B streptococci. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 418:995-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng, S., and R. Haselkorn. 1996. A glutamate/glutamine/aspartate/asparagine transport operon in Rhodobacter capsulatus. Mol. Microbiol. 20:1001-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu, X., J. Garrett, J. Schreve, and T. Michaeli. 1996. GNP1, the high-affinity glutamine permease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 30:107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]