Abstract

In lantibiotic lacticin 481 biosynthesis, LctT cleaves the precursor peptide and exports mature lantibiotic. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry revealed that a truncated form of lacticin 481 is produced in the absence of LctT or after cleavage site inactivation. Production of truncated lacticin 481 is 4-fold less efficient, and its specific activity is about 10-fold lower.

Lacticin 481 is a lactococcal antimicrobial peptide (bacteriocin) of the lantibiotic family (6). This peptide is the most extensively studied member of a lantibiotic subgroup named the lacticin 481 group (23). The unusual residues of lacticin 481 (Fig. 1) are obtained by posttranslational modifications of LctA, the precursor peptide encoded by the structural gene lctA (16, 19). In addition to lctA, the lacticin 481 operon includes the five genes lctMTFEG (7, 19, 20). Similar genes, collectively named lanAMTFEG, were found in the operons for lantibiotics of the lacticin 481 group (2, 14, 15). The functions of the lctM and lctFEG products were experimentally determined: LctM creates the unusual residues in LctA (25, 27), and LctFEG constitutes an immunity system protecting the lacticin 481 producer strain against its own lantibiotic (20). The functions of the proteins encoded by lanT genes of the lacticin 481 group were deduced from their similarities to ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters possessing an N-terminal protease domain. These transporters display the dual function of cleaving the leader peptide and exporting bacteriocins possessing double-glycine-type leader peptides (9, 11). Such leader peptides contain the residues GG, GS, or GA at positions −2 and −1 relative to the cleavage site (11, 14). Precursor cleavage and lantibiotic export should be essential steps in lantibiotic production. Consistently, inactivation of mutT (the lanT gene of the operon for mutacin II, a lacticin 481-related lantibiotic) abolished mutacin II production (2). By contrast, we observed that LctT is dispensable for lacticin 481 production (19). Here, we characterized the antimicrobial peptide produced when preventing maturation by LctT.

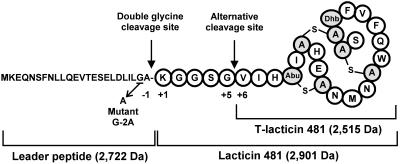

FIG. 1.

Production of lacticin 481 and T-lacticin 481. The lacticin 481 precursor peptide LctA consists of an N-terminal leader peptide and a C-terminal propeptide. The unusual residues lanthionine (alanine-S-alanine), 3-methyllanthionine (aminobutyric acid [Abu]-S-alanine), and 2,3-didehydrobutyrine (Dhb) are created in the propeptide moiety by enzymatic modification of serine, threonine, and cysteine residues. Lacticin 481 is obtained after cleavage of the leader peptide at the double-glycine site. When this step is prevented, cleavage occurs mainly at the alternative site.

LctT is necessary for high-level production of lacticin 481.

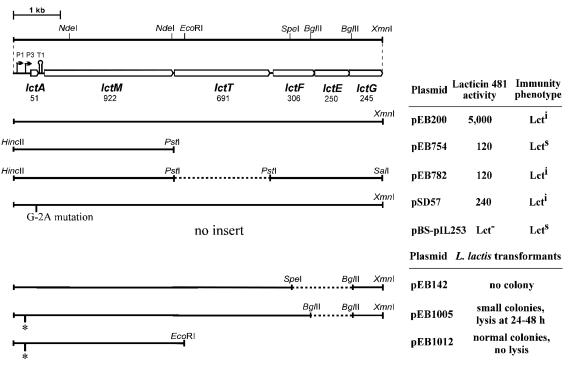

To examine more precisely the involvement of LctT in lacticin 481 production, we assayed the antimicrobial activities secreted by Lactococcus lactis IL1403 bearing various combinations of lct genes (Fig. 2). The activities were 40-fold lower when lctT was absent (pEB754 and pEB782 versus pEB200). Whereas lctAM could be expressed without lctFEG (pEB754, pEB1012), lctAMT constructions (pEB142, pEB1005) were toxic to L. lactis IL1403, even when transcription of the lct genes was reduced by inactivation of promoter P3 (pEB1005). High-level production of extracellular lacticin 481 activity thus requires LctT and the immunity system LctFEG.

FIG. 2.

Lacticin 481 activities induced by genes of the lacticin 481 operon introduced into L. lactis IL1403. The six lct genes (open boxes) of the lacticin 481 operon and the positions of some restriction sites are shown at the top. P1 and P3 are the promoters, and T1 is a terminator. The numbers of residues in the encoded proteins are given. Continuous lines show the plasmid inserts, whereas dashed lines represent lacking parts within the lacticin 481 operon. * and G-2A indicate mutations inactivating promoter P3 and the LctA cleavage site, respectively. Lacticin 481 activities are in arbitrary units per milliliter of culture supernatant. The same values were obtained in at least three experiments with L. lactis IL1835 as the indicator strain. Lct−, no lacticin 481 production; Lcts, lacticin 481 sensitive; Lcti, lacticin 481 immune.

Lacticin 481 is produced in a truncated form (T-lacticin 481) when LctT is unable to process its precursor.

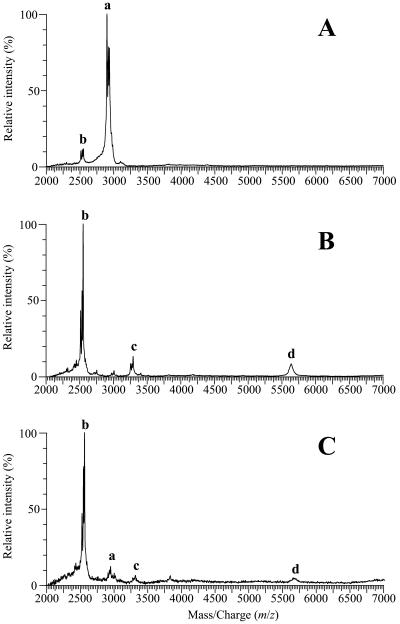

To examine the location of the cleavage site in the absence of LctT, we determined the mass of the lantibiotic by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) performed on whole bacteria grown on a plate (12). When L. lactis IL1403 contained lctAMTFEG, lacticin 481 yielded a peak cluster (Fig. 3A, cluster a) with three peaks at m/z 2,902, 2,924, and 2,940 (mass/charge ratio, where z is usually 1). These peaks are due to the molecular ion [M + H]+ and to the adduct ions [M + Na]+ and [M + K]+ of lacticin 481, respectively (12). Without lctT (pEB782), a major peak cluster was detected (Fig. 3B, cluster b), but at lower m/z values of 2,516, 2,538, and 2,554, revealing a peptide mass of 2,515 Da. This is consistent with the mass of a lacticin 481 molecule lacking its five N-terminal residues (Fig. 1). This peptide is a product of the lctAMFEG genes since it was not observed on spectra obtained from L. lactis IL1403 (12) or IL1403(pBS-pIL253) (data not shown). Wild-type lacticin 481 was not detected in the absence of LctT since no peak appeared in the m/z range of 2,902 to 2,940 in Fig. 3B. By contrast, L. lactis IL-1403(pEB200) produced a small amount of T-lacticin 481 (Fig. 3A, cluster b). The absence of LctT thus prevents the cleavage of LctA at its normal site and the major peptide produced is then T-lacticin 481.

FIG. 3.

MALDI-TOF mass spectra of whole L. lactis IL1403 cells transformed by pEB200 carrying lctAMTFEG (A), pEB782 bearing all of the lct genes except lctT (B), and pSD57 with all of the lct genes and the G-2A mutation in lctA (C). Peak clusters a and b are due to lacticin 481 and T-lacticin 481, respectively. Peak cluster c (around m/z 3,292) and peak d (m/z 5,635) could be due to LctA cleaved within the leader peptide and to uncleaved LctA with its modified residues, respectively.

To prevent normal processing of LctA in the presence of LctT, we inactivated the LctA cleavage site by replacing the glycine at position −2 with alanine (Fig. 1). This mutation was chosen because G-2 is conserved in the leader peptides of bacteriocins processed by ABC transporters (11, 14) and the G-2A mutant of premutacin II was neither cleaved nor secreted (3). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed on pTH999 (Table 1) with the Altered Sites in vitro mutagenesis system (Promega) and the oligonucleotide CCTTATTTTAGCTGCAAAAGGCG. The mutated lctA gene was cloned into pEFΔMTFEG as previously described (12, 13), and the resulting plasmid was fused to pIL253, creating pSD57. A low level of antimicrobial activity was produced by IL1403(pSD57) (Fig. 2), and the MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of this strain (Fig. 3C) was similar to that of IL1403(pEB782) (Fig. 3B). Inactivating the LctA cleavage site and deleting lctT therefore had the same overall effect and led to the predominant production of T-lacticin 481, experimentally showing that LctT is responsible for specific LctA cleavage. The IL1403(pSD57) spectrum includes minor peak cluster a (Fig. 3C), indicating that the G-2A mutation did not completely prevent wild-type lacticin 481 production. This could explain why the antimicrobial activity of IL1403(pSD57) was twice that of IL1403(pEB782).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Lactococcus lactis strains | ||

| IL1403 | Plasmid-free strain, bacteriocin nonproducer | 4 |

| IL1835 | IL1403 containing pIL252 (Emr), lacticin 481 sensitive | 22 |

| VEL8702 | IL1403 derivative, htrA mutant (htrA::pVE8039), Cmr | 8, 18 |

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| JM109 | Host for cloning and plasmid propagation | 21 |

| ES1301 mutS | Mismatch repair-negative strain for site-directed mutagenesis | Promega |

| Plasmids | ||

| pALTER-1 | E. coli vector for site-directed mutagenesis, Tetr | Promega |

| pBSb | E. coli cloning vector, Apr | Stratagene |

| pIL253 | L. lactis cloning vector, Emr | 22 |

| pBS-pIL253 | E. coli-L. lactis shuttle vector, fusion of pBS and pIL253 | 20 |

| pEF94 | Lacticin 481 operon carried by pBS | 20 |

| pEFΔMTFEG | Lacticin 481 operon lacking its promoter region and lctA in pBS | 13 |

| pEB142 | pEB200 lacking the SpeI-BglII fragment (lctFEG) | This study |

| pEB200 | Lacticin 481 operon carried by pBS-pIL253 | 25 |

| pEB754 | PCR fragment containing lctAM cloned into pBS-pIL253 | 24 |

| pEB782 | PCR fragment containing lctFEG (amplified from pEF94 with primers LCTF1 [TTATACTGCAGTAAAGTTACGTATCGCTGT] and T3) cloned into the PstI-SalI sites of pEB754 | This study |

| pEB1001 | Lacticin 481 operon with promoter P3 inactivated, in pBS-pIL253 | 13 |

| pEB1005 | pEB1001 lacking the BglII fragment (lctFEG) | This study |

| pEB1012 | pEB1001 lacking the EcoRI fragment (lctTFEG) | This study |

| pTH999 | SacI-HindIII DNA fragment containing the lacticin 481 operon 5′ end (promoter region, lctA, and beginning of lctM) in pALTER-1 | 13 |

| pSD57 | Lacticin 481 operon with the mutation G-2A in lctA, in pBS-pIL253 | This study |

Apr, Cmr, Emr, and Tetr, resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and tetracycline, respectively.

pBS, pBluescript.

Comparison of the amounts of wild-type lacticin 481 and T-lacticin 481 produced.

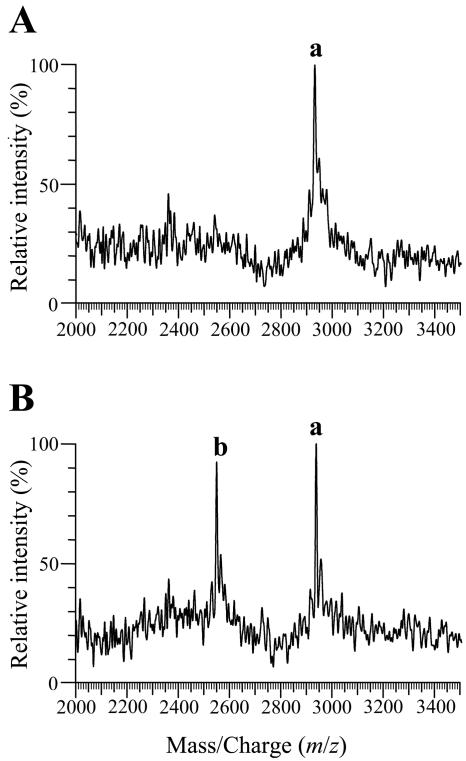

Supernatants from liquid cultures were analyzed by MALDI-TOF MS as previously described (12). Whereas lacticin 481 was detected from supernatants diluted up to fourfold, T-lacticin 481 was detected only from undiluted supernatants, indicating that the amount of lacticin 481 secreted is four times that of T-lacticin 481. This estimation was verified by mixing supernatants: clusters a and b were observed at comparable intensities when IL1403(pEB754) and IL1403(pEB200) culture supernatants were mixed at a 4:1 ratio (Fig. 4). The extracellular production of the antimicrobial peptide is thus fourfold less efficient in the absence of LctT. Since IL1403(pEB754) produced a maximal antimicrobial activity 40-fold lower than that of IL1403(pEB200) (Fig. 2), the specific activity of T-lacticin 481 is about 10-fold lower than that of lacticin 481. Although the N-terminal lysine is not essential to lacticin 481 activity (27), it would have been surprising if lacticin 481 could retain its full biological activity without its five N-terminal residues (Fig. 1).

FIG. 4.

MALDI-TOF mass spectra of culture supernatant mixtures. L. lactis IL1403(pEB754) and IL1403(pEB200) culture supernatants were mixed at 1:1 (A) and 4:1 (B) ratios. These strains produce T-lacticin 481 (peak cluster b) and wild-type lacticin 481 (peak cluster a), respectively.

LctA cleavage in the absence of LctT is not due to HtrA.

It is unlikely that an ABC transporter with a protease domain is involved in T-lacticin 481 production, since such a protease would use a double-glycine site. Consistently, the LcnC homologue encoded by L. lactis IL1403 (26) is not responsible for T-lacticin 481 production (24). The cleavage and export leading to T-lacticin 481 production thus likely rely on distinct enzymes. The L. lactis IL1403 genome encodes numerous ABC transporters devoid of a protease domain (1). As some of these transporters have broad substrate specificity (17), one of them could export LctA and/or T-lacticin 481. The maturation of subtilin, a lantibiotic of the nisin group (23), does not rely on a dedicated protease but is due to three extracellular proteases of Bacillus subtilis (5). Similarly, the bacteriocin LsbA is secreted by L. lactis under its precursor form, which is then cleaved by HtrA (10). Since HtrA is the unique surface housekeeping protease in L. lactis IL1403 (18), it could be involved in LctA processing if the latter is first secreted. We examined this hypothesis by introducing pEB782 (lctAMFEG) into IL-1403 htrA mutant strain VEL8702 (8, 18). The MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of the resulting strain was very similar to that of IL1403(pEB782) (Fig. 3B), showing that HtrA is not responsible for LctA cleavage in the absence of LctT. Furthermore, we failed to inhibit the cleavage by including protease inhibitors in solid medium before growing IL1403(pEB782). In cytoplasmic extracts of this strain, low-intensity peaks likely due to T-lacticin 481 were detected by MALDI-TOF MS (data not shown), supporting an alternative model in which LctA is cleaved intracellularly.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to I. Poquet (INRA, Jouy en Josas, France) for kindly providing L. lactis strain VEL8702.

P.U. and T.H. were the recipients of doctoral fellowships from the Région Bretagne and from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie, France, respectively. Our laboratory is supported by grants from the Région Bretagne and by European FEDER funds.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bolotin, A., P. Wincker, S. Mauger, O. Jaillon, K. Malarme, J. Weissenbach, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Sorokin. 2001. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11:731-753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen, P., F. Qi, J. Novak, and P. W. Caufield. 1999. The specific genes for lantibiotic mutacin II biosynthesis in Streptococcus mutans T8 are clustered and can be transferred en bloc. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1356-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, P., F. Qi, J. Novak, R. E. Krull, and P. W. Caufield. 2001. Effect of amino acid substitutions in conserved residues in the leader peptide on biosynthesis of the lantibiotic mutacin II. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 195:139-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chopin, A., M. C. Chopin, A. Moillo-Batt, and P. Langella. 1984. Two plasmid-determined restriction and modification systems in Streptococcus lactis. Plasmid 11:260-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corvey, C., T. Stein, S. Düsterhus, M. Karas, and K.-D. Entian. 2003. Activation of subtilin precursors by Bacillus subtilis extracellular serine proteases subtilisin (AprE), WprA, and Vpr. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 304:48-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dufour, A., A. Rincé, T. Hindré, D. Haras, and J.-P. Le Pennec. 2003. Lacticin 481: an antimicrobial peptide of the lantibiotic family produced by Lactococcus lactis. Recent Res. Dev. Bacteriol. 1:219-234. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dufour, A., A. Rincé, P. Uguen, and J.-P. Le Pennec. 2000. IS1675, a novel lactococcal insertion element, forms a transposon-like structure including the lacticin 481 lantibiotic operon. J. Bacteriol. 182:5600-5605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foucaud-Scheunemann, C., and I. Poquet. 2003. HtrA is a key factor in the response to specific stress conditions in Lactococcus lactis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 224:53-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke, C. M., J. Tiemersma, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1999. Membrane topology of the lactococcal bacteriocin ATP-binding cassette transporter protein LcnC. Involvement of LcnC in lactococcin A maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8484-8490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gajic, O., G. Buist, M. Kojic, L. Topisirovic, O. P. Kuipers, and J. Kok. 2003. Novel mechanism of bacteriocin secretion and immunity carried out by lactococcal multidrug resistance proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278:34291-34298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Håvarstein, L. S., D. B. Diep, and I. F. Nes. 1995. A family of bacteriocin ABC transporters carry out proteolytic processing of their substrates concomitant with export. Mol. Microbiol. 16:229-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hindré, T., S. Didelot, J.-P. Le Pennec, D. Haras, A. Dufour, and K. Vallée-Réhel. 2003. Bacteriocin detection from whole bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1051-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hindré, T., J.-P. Le Pennec, D. Haras, and A. Dufour. 2004. Regulation of lantibiotic lacticin 481 production at the transcriptional level by acid pH. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAuliffe, O., R. P. Ross, and C. Hill. 2001. Lantibiotics: structure, biosynthesis and mode of action. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25:285-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLaughlin, R. E., J. J. Ferretti, and W. L. Hynes. 1999. Nucleotide sequence of the streptococcin A-FF22 lantibiotic regulon: model for production of the lantibiotic SA-FF22 by strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 175:171-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piard, J.-C., O. P. Kuipers, H. S. Rollema, M. J. Desmazeaud, and W. M. de Vos. 1993. Structure, organization, and expression of the lct gene for lacticin 481, a novel lantibiotic produced by Lactococcus lactis. J. Biol. Chem. 268:16361-16368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poelarends, G. J., P. Mazurkiewicz, and W. N. Konings. 2002. Multidrug transporters and antibiotic resistance in Lactococcus lactis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1555:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poquet, I., V. Saint, E. Seznec, N. Simoes, A. Bolotin, and A. Gruss. 2000. HtrA is the unique surface housekeeping protease in Lactococcus lactis and is required for natural protein processing. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1042-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rincé, A., A. Dufour, S. Le Pogam, D. Thuault, C. M. Bourgeois, and J.-P. Le Pennec. 1994. Cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of genes involved in production of lactococcin DR, a bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1652-1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rincé, A., A. Dufour, P. Uguen, J.-P. Le Pennec, and D. Haras. 1997. Characterization of the lacticin 481 operon: the Lactococcus lactis genes lctF, lctE, and lctG encode a putative ABC transporter involved in bacteriocin immunity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4252-4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Simon, D., and A. Chopin. 1988. Construction of a vector plasmid family and its use for molecular cloning in Streptococcus lactis. Biochimie 70:559-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Twomey, D., R. P. Ross, M. Ryan, B. Meaney, and C. Hill. 2002. Lantibiotics produced by lactic acid bacteria: structure, function and applications. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 82:165-185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uguen, M., and P. Uguen. 2002. The LcnC homologue cannot replace LctT in lacticin 481 export. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 208:99-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uguen, P., J.-P. Le Pennec, and A. Dufour. 2000. Lantibiotic biosynthesis: interactions between prelacticin 481 and its putative modification enzyme, LctM. J. Bacteriol. 182:5262-5266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venema, K., M. H. R. Dost, P. A. H. Beun, A. J. Haandrikman, G. Venema, and J. Kok. 1996. The genes for secretion and maturation of lactococcins are located on the chromosome of Lactococcus lactis IL1403. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1689-1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie, L., L. M. Miller, C. Chatterjee, O. Averin, N. L. Kelleher, and W. A. van der Donk. 2004. Lacticin 481: in vitro reconstitution of lantibiotic synthetase activity. Science 303:679-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]