Abstract

The efficacy and safety of telavancin is under evaluation for the treatment of subjects with complicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and S. aureus right-sided infective endocarditis. This study evaluated the telavancin activity against a global collection of S. aureus causing bloodstream infections (BSI), including endocarditis, to support the development of bacteremia/endocarditis clinical indications. This study included a total of 4191 S. aureus [1490 methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)], which were unique (one per patient) clinical isolates recovered from blood samples collected during 2011–2014 in a global network of hospitals. All isolates were deemed responsible for BSI, including endocarditis, by local guidelines. Isolates were tested for susceptibility by broth microdilution. Telavancin (MIC50/90, 0.03/0.06 μg/ml) inhibited all S. aureus at ≤0.12 μg/ml, the breakpoint for susceptibility. Equivalent minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values (MIC50/90, 0.03/0.06 μg/ml) were obtained for telavancin against methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and MRSA isolates, as well as MRSA from community and healthcare origins. Similar telavancin activities (MIC50, 0.03 μg/ml) were observed against MRSA subsets from North America and Europe, while isolates from the Asia-Pacific (APAC) and Latin America regions had MIC50 values of 0.06 μg/ml. MRSA with vancomycin MIC values of 2–4 μg/ml and the multidrug resistance (MDR) subset had telavancin MIC50 results of 0.06 μg/ml, although the MIC100 result obtained against these subsets remained identical to those of MSSA (MIC100, 0.12 μg/ml, respectively). This study updates the telavancin in vitro activity, which continues to demonstrate great potency against invasive S. aureus, regardless of the susceptibility phenotype or demographic characteristics (100.0% susceptible), and supports the sought-after subsequent indications.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is the second most common cause of bloodstream infection (BSI), and is the most important cause of BSI-associated death [1]. Prevalence-based studies, such as the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, observed a rate of 44.3% of S. aureus [45.4% methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)] causing bacteremia in USA hospitals during the 2015 sampling year (unpublished JMI data). Among multicenter and population-based investigations, incidence rates of 15–40 per 100,000 population per year have been identified, with case-fatality rates of approximately 15–25% [1–3].

Telavancin is a once-daily parenteral semi-synthetic lipoglycopeptide agent approved in the United States, Europe, and Canada for clinical indications, such as complicated skin and skin structure infections and/or hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia (see package inserts for a complete description of respective indications) [4]. The efficacy and safety of telavancin is also under evaluation for the treatment of subjects with complicated S. aureus bacteremia and S. aureus right-sided infective endocarditis (NCT02208063) [5]. The in vitro activity of telavancin has been monitored and reported previously. However, this study evaluated the telavancin activity against a recent and global collection of S. aureus bacteremia isolates, including those responsible for endocarditis, to support the sought-after bacteremia/endocarditis clinical indications.

Materials and methods

This study included a total of 4191 S. aureus (1490 MRSA), which were unique (one per patient) clinical isolates recovered from blood samples collected during 2011–2014 in a global network of hospitals in the North America (2150 isolates), Europe (1283), Latin America (473), and Asia-Pacific (APAC; 285) regions. All isolates were deemed responsible for BSI, including endocarditis, by the participating site according to local guidelines. Isolates that met the protocol selection criteria had the bacterial identification initially performed by the participating laboratory, which submitted isolates to a central monitoring laboratory (JMI Laboratories, North Liberty, IA, USA), as part of the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Bacterial identification was subsequently confirmed by the reference monitoring laboratory by standard algorithms. Isolates showing questionable phenotypic and/or biochemical results had the bacterial identification confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS; Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany).

Isolates were tested for susceptibility by broth microdilution following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M07-A10 document [6]. Testing was performed using panels manufactured by Thermo Fisher Scientific (Cleveland, OH, USA). These validated panels provide minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) results equivalent to the CLSI-approved broth microdilution method, which includes 0.002% polysorbate 80 in the testing media [6]. Bacterial inoculum density was monitored by colony counts to assure an adequate number of cells for each testing event. Quality of the MIC values was assured by concurrent testing of CLSI-recommended quality control (QC) reference strains (S. aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212) [6]. All QC results were within published acceptable ranges [6]. MIC interpretations for comparator agents were based on the CLSI M100-S26 [7] and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [8] criteria, as available. Data analysis was performed by grouping isolates based on infection type, geographic region, and community-acquired (CA) and healthcare-associated (HA) origin based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria [9] and antimicrobial susceptibility phenotype. The latter applied the oxacillin breakpoint for grouping methicillin-susceptible (MSSA) and -resistant (MRSA) isolates and the vancomycin MIC results for segregating S. aureus between those with vancomycin MIC values of ≤1 or 2–4 μg/ml. Isolates were also categorized based on multidrug resistance (MDR), defined as MRSA isolates (methicillin [oxacillin]-resistant) resistant to an additional three or more drug classes (see Table 2 for a complete list of antimicrobials utilized).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of telavancin and comparator agents tested against a global collection of resistant subsets of S. aureus clinical isolates responsible for bloodstream infections, including endocarditis

| Organism (number tested)/antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) | % susceptible/% intermediate/% resistanta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | CLSI | EUCAST | |||||

| MRSA (1490) | |||||||||

| Telavancin | ≤0.015–0.12 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 100.0 | – | –b | 100.0 | – | 0.0 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25–>2 | ≤0.25 | >2 | 63.7 | 0.2 | 36.1 | 63.5 | 0.2 | 36.3 |

| Daptomycin | 0.12–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 99.7 | – | – | 99.7 | – | 0.3 |

| Erythromycin | ≤0.12–>16 | >16 | >16 | 18.8 | 2.8 | 78.4 | 19.1 | 0.6 | 80.3 |

| Gentamicin | ≤1–>8 | ≤1 | >8 | 87.7 | 0.4 | 11.9 | 87.3 | – | 12.7 |

| Levofloxacin | ≤0.12–>4 | >4 | >4 | 24.9 | 1.5 | 73.6 | 24.9 | 1.5 | 73.6 |

| Linezolid | 0.25–4 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | – | 0.0 | 100.0 | – | 0.0 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.5–>8 | ≤0.5 | 2 | 92.3 | 0.4 | 7.3 | 89.6 | 2.2 | 8.1 |

| TMP-SMX | ≤0.5–>4 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 97.7 | – | 2.3 | 97.7 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| Vancomycin | 0.25–4 | 1 | 1 | 99.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 99.9 | – | 0.1 |

| MRSA MDR (569) | |||||||||

| Telavancin | ≤0.015–0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 100.0 | – | – | 100.0 | – | 0.0 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25–>2 | >2 | >2 | 9.3 | 0.4 | 90.3 | 9.0 | 0.4 | 90.7 |

| Daptomycin | 0.12–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 99.3 | – | – | 99.3 | – | 0.7 |

| Erythromycin | 0.5–>16 | >16 | >16 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 97.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 98.9 |

| Gentamicin | ≤1–>8 | ≤1 | >8 | 71.9 | 0.5 | 27.6 | 71.5 | – | 28.5 |

| Levofloxacin | ≤0.12–>4 | >4 | >4 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 98.6 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 98.6 |

| Linezolid | 0.25–4 | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | – | 0.0 | 100.0 | – | 0.0 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.5–>8 | ≤0.5 | >8 | 89.1 | 0.0 | 10.9 | 84.0 | 5.1 | 10.9 |

| TMP-SMX | ≤0.5–>4 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 94.6 | – | 5.4 | 94.6 | 0.4 | 5.1 |

| Vancomycin | 0.5–4 | 1 | 1 | 99.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 99.8 | – | 0.2 |

| MRSA with vancomycin MIC = 2–4 μg/ml (51) | |||||||||

| Telavancin | ≤0.015–0.12 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 100.0 | – | – | 100.0 | – | 0.0 |

| Clindamycin | ≤0.25–>2 | >2 | >2 | 25.5 | 0.0 | 74.5 | 25.5 | 0.0 | 74.5 |

| Daptomycin | 0.25–2 | 0.5 | 1 | 98.0 | – | – | 98.0 | – | 2.0 |

| Erythromycin | ≤0.12–>16 | >16 | >16 | 9.8 | 2.0 | 88.2 | 9.8 | 2.0 | 88.2 |

| Gentamicin | ≤1–>8 | ≤1 | >8 | 72.5 | 0.0 | 27.5 | 72.5 | – | 27.5 |

| Levofloxacin | ≤0.12–>4 | >4 | >4 | 13.7 | 0.0 | 86.3 | 13.7 | 0.0 | 86.3 |

| Linezolid | 0.25–2 | 1 | 2 | 100.0 | – | 0.0 | 100.0 | – | 0.0 |

| Tetracycline | ≤0.5–>8 | ≤0.5 | 2 | 90.2 | 0.0 | 9.8 | 84.3 | 5.9 | 9.8 |

| TMP-SMX | ≤0.5–>4 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 | 94.1 | – | 5.9 | 94.1 | 0.0 | 5.9 |

| Vancomycin | 2–4 | 2 | 2 | 98.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 98.0 | – | 2.0 |

MRSA methicillin-resistant S. aureus, TMP-SMX trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, MDR multidrug resistance (defined as MRSA resistant to three or more drug classes in addition to β-lactam agents)

aBreakpoint criteria according to the CLSI (M100-S26, 2016) and EUCAST, as available

Results and discussion

Overall, S. aureus isolates were 100.0% susceptible to telavancin and had the highest MIC50, MIC90, and MIC100 results of 0.03, 0.06, and 0.12 μg/ml, respectively. Equivalent MIC values (MIC50/90, 0.03/0.06 μg/ml) were obtained for telavancin against isolates from different infection types (i.e., BSI and endocarditis), MSSA and MRSA isolates, as well as MRSA from CA and HA origins (Table 1). Telavancin (MIC50/90, 0.03/0.06 μg/ml) had similar potency against all S. aureus and the MRSA subsets from North America and Europe. The isolates from the APAC and Latin America regions had slightly higher MIC50 values (MIC50/90, 0.06/0.06 μg/ml), although the MIC90 and MIC100 results remained identical to those obtained for the overall MSSA population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) distributions for telavancin when tested against Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates, as part of the international telavancin surveillance program

| S. aureus/Parameter (number tested) | MIC (μg/ml) | Number (cumulative %) inhibited at a telavancin MIC (μg/ml) of: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% | 90% | ≤0.015 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| All (4191) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 169 (4.0) | 2465 (62.8) | 1538 (99.5) | 19 (100.0) |

| Infection type | ||||||

| BSI (4149) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 166 (4.0) | 2444 (62.9) | 1520 (99.5) | 19 (100.0) |

| Endocarditis (42) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 3 (7.1) | 21 (57.1) | 18 (100.0) | |

| Origin | ||||||

| CA-MRSA (828) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 24 (2.9) | 482 (61.1) | 312 (98.8) | 10 (100.0) |

| HA-MRSA (552) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 15 (2.7) | 284 (54.2) | 250 (99.5) | 3 (100.0) |

| Phenotype | ||||||

| MSSA (2701) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 127 (4.7) | 1632 (65.1) | 938 (99.9) | 4 (100.0) |

| MRSA (1490) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 42 (2.8) | 833 (58.7) | 600 (99.0) | 15 (100.0) |

| MDR (569) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 8 (1.4) | 264 (47.8) | 285 (97.9) | 12 (100.0) |

| Non-MDR (921) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 34 (3.7) | 569 (65.5) | 315 (99.7) | 3 (100.0) |

| Vancomycin MIC ≤1 μg/ml (1439) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 41 (2.8) | 828 (60.4) | 561 (99.4) | 9 (100.0) |

| Vancomycin MIC = 2–4 μg/ml (51) | 0.06 | 0.12 | 1 (2.0) | 5 (11.8) | 39 (88.2) | 6 (100.0) |

| Region | ||||||

| North America (2150) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 102 (4.7) | 1374 (68.7) | 662 (99.4) | 12 (100.0) |

| MRSA (938) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 30 (3.2) | 586 (65.7) | 311 (98.8) | 11 (100.0) |

| Europe (1283) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 52 (4.1) | 798 (66.3) | 430 (99.8) | 3 (100.0) |

| MRSA (290) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 10 (3.4) | 174 (63.4) | 105 (99.7) | 1 (100.0) |

| Latin America (473) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 13 (2.7) | 206 (46.3) | 250 (99.2) | 4 (100.0) |

| MRSA (175) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1 (0.6) | 47 (27.4) | 124 (98.3) | 3 (100.0) |

| APAC (285) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 2 (0.7) | 87 (31.2) | 196 (100.0) | |

| MRSA (87) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1 (1.1) | 26 (31.0) | 60 (100.0) | |

BSI bloodstream infection, MSSA methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, MRSA methicillin-resistant S. aureus, CA-MRSA community-acquired MRSA, HA-MRSA healthcare-associated MRSA; the origin of the isolate was defined based on CDC criteria, MDR multidrug resistance, defined as MRSA (methicillin [oxacillin]-resistant) resistant to three or more drug classes in addition to β-lactam agents

MRSA with vancomycin MIC values of 2–4 μg/ml and the MDR subset had telavancin MIC50 results of 0.06 μg/ml, which was 2-fold higher than the telavancin MIC50 results (MIC50, 0.03 μg/ml) for the isolates exhibiting vancomycin MIC values at ≤1 μg/ml or a non-MDR phenotype. Even though the MIC50 was higher in these resistant subgroups, telavancin still inhibited all isolates at the susceptible breakpoint of ≤0.12 μg/ml (Table 1). Daptomycin (MIC50/90, 0.5/1 μg/ml; Table 2) also demonstrated higher MIC results when tested against MRSA exhibiting vancomycin MIC values of 2–4 μg/ml compared with those isolates with vancomycin MIC values of ≤1 μg/ml (data not shown).

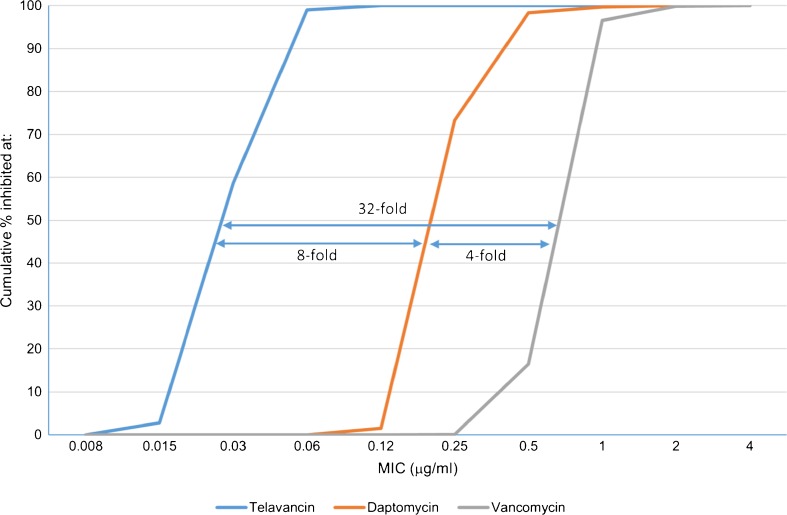

Overall, telavancin showed MIC50 results 8-fold lower than daptomycin (MIC50/90, 0.25/0.5 μg/ml) and up to 32-fold lower than vancomycin (MIC50/90, 1/1 μg/ml) against bacteremia MRSA, including those causing endocarditis (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Similarly, the telavancin MIC results (MIC50/90, 0.06/0.06 μg/ml) were 4- to 8-fold lower than those obtained by daptomycin (MIC50/90, 0.25/0.5 μg/ml) and 16-fold lower than vancomycin (MIC50/90, 1/1 μg/ml) against the MRSA MDR subset (Table 2). When tested against the MRSA subset displaying decreased susceptibility to vancomycin (MIC, 2–4 μg/ml), telavancin (MIC50/90, 0.06/0.12 μg/ml) and daptomycin (MIC50/90, 0.5/1 μg/ml) were the most potent agents; however, telavancin was 8-fold more potent than daptomycin (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Telavancin, daptomycin, and vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) distributions obtained against all bacteremia methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Data are presented as the cumulative percentage of isolates inhibited at each MIC (μg/ml). MIC50 differences between drugs are depicted

Telavancin demonstrated potent in vitro activity against this contemporary global collection of S. aureus causing bacteremia, including resistant subsets and isolates causing endocarditis. In addition, telavancin had in vitro potency at least 4-fold greater than other clinically available comparator antimicrobial agents (daptomycin and vancomycin) recommended by the current Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines for the treatment of bacteremia caused by MRSA and MDR subsets [10]. These in vitro results support further investigations of telavancin as a candidate for the treatment of bacteremia caused by S. aureus and resistant subsets, including those isolates responsible for endocarditis [11]. Moreover, the results obtained for telavancin corroborate those reported previously and indicate sustained in vitro potency over time against S. aureus isolates causing infections in hospitals worldwide [12–14].

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the following staff members at JMI Laboratories (North Liberty, Iowa, USA): L. Duncan, L. Flanigan, M. Huband, M. Janechek, J. Oberholser, P. Rhomberg, J. Schuchert, J. Streit, and L. Woosley for their technical support and/or assistance with manuscript preparation.

Compliance with ethical standards

Funding

The research and publication process was supported by Theravance Biopharma Antibiotics, Inc.

Conflict of interest

JMI Laboratories, Inc. has also received research and educational grants from Achaogen, Actavis, Actelion, Allergan, American Proficiency Institute (API), AmpliPhi, Anacor, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Basilea, Bayer, BD, Cardeas, Cellceutix, CEM-102 Pharmaceuticals, Cempra, Cerexa, Cidara, CorMedix, Cubist, Debiopharm, Dipexium, Dong Wha, Durata, Enteris, Exela, Forest Research Institute, Furiex, Genentech, GSK, Helperby, ICPD, Janssen, Lannett, Longitude, Medpace, Meiji Seika Kasha, Melinta, Merck, Motif, Nabriva, Novartis, Paratek, Pfizer, Pocared, PTC Therapeutics, Rempex, Roche, Salvat, Scynexis, Seachaid, Shionogi, Tetraphase, The Medicines Company, Theravance, Theravance Biopharma Antibiotics Inc., Thermo Fisher, VenatoRx, Vertex, Wockhardt, and Zavante. Some JMI employees are advisors/consultants for Allergan, Astellas, Cubist, Pfizer Cempra, and Theravance. In regards to speakers’ bureaus and stock options: none to declare. JIS was an employee of Theravance Biopharma US, Inc. when this surveillance study was conducted and during the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Tong SY, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, Holland TL, Fowler VG., Jr Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):603–661. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00134-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laupland KB, Lyytikäinen O, Søgaard M, Kennedy KJ, Knudsen JD, Ostergaard C, Galbraith JC, Valiquette L, Jacobsson G, Collignon P, Schønheyder HC, International Bacteremia Surveillance Collaborative The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: a multinational population-based surveillance study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(5):465–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, Harrison LH, Lynfield R, Dumyati G, Townes JM, Craig AS, Zell ER, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Fridkin SK, Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(15):1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.VIBATIV Package Insert (2016) Theravance

- 5.Friedman B, Bressler A, Cleveland K, Lat A, Helgeson M, Sherman C, Castaneda-Ruiz B. 686: telavancin observational use registry: preliminary results for bacteremia and endocarditis. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12 Suppl 1):248. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000509363.39114.5c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M07-A10. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard—tenth edition. Wayne: CLSI; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100-S25. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fifth informational supplement. Wayne: CLSI; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (2016) Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 6.0, January 2016. Available online at: http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/. Accessed Jan 2016

- 9.Kreisel K, Roghmann MC, Shardell M, Stine OC, Perencevich E, Lesse A, Gordin F, Climo M, Johnson JK. Assessment of the 48-hour rule for identifying community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection complicated by bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(6):657–659. doi: 10.1086/653068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, J Rybak M, Talan DA, Chambers HF, Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):e18–e55. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corey GR, Rubinstein E, Stryjewski ME, Bassetti M, Barriere SL. Potential role for telavancin in bacteremic infections due to gram-positive pathogens: focus on Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(5):787–796. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendes RE, Sader HS, Flamm RK, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. Telavancin in vitro activity against a collection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates, including resistant subsets, from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(3):1811–1814. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04616-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendes RE, Farrell DJ, Sader HS, Streit JM, Jones RN. Update of the telavancin activity in vitro tested against a worldwide collection of Gram-positive clinical isolates (2013), when applying the revised susceptibility testing method. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;81(4):275–279. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendes RE, Flamm RK, Farrell DJ, Sader HS, Jones RN. Telavancin activity tested against Gram-positive clinical isolates from European, Russian and Israeli hospitals (2011–2013) using a revised broth microdilution testing method: redefining the baseline activity of telavancin. J Chemother. 2016;28(2):83–88. doi: 10.1179/1973947815Y.0000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]