Abstract

Two episodes of mortality of cultured carpet shell clams (Ruditapes decussatus) associated with bacterial infections were recorded during 2001 and 2002 in a commercial hatchery located in Spain. Vibrio alginolyticus was isolated as the primary organism from moribund clam larvae that were obtained during the two separate events. Vibrio splendidus biovar II, in addition to V. alginolyticus, was isolated as a result of a mixed Vibrio infection from moribund clam larvae obtained from the second mortality event. The larval mortality rates for these events were 62 and 73%, respectively. Mortality was also detected in spat. To our knowledge, this is the fist time that these bacterial species have been associated with larval and juvenile carpet shell clam mortality. The bacterial strains were identified by morphological and biochemical techniques and also by PCR and sequencing of a conserved region of the 16S rRNA gene. In both cases bacteria isolated in pure culture were inoculated into spat of carpet shell clams by intravalvar injection and by immersion. The mortality was attributed to the inoculated strains, since the bacteria were obtained in pure culture from the soft tissues of experimentally infected clams. V. alginolyticus TA15 and V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 caused similar histological lesions that affected mainly the mantle, the velum, and the connective tissue of infected organisms. The general enzymatic activity of both live cells and extracellular products (ECPs), as evaluated by the API ZYM system, revealed that whole bacterial cells showed greater enzymatic activity than ECPs and that the activity of most enzymes ceased after heat treatment (100°C for 10 min). Both strain TA15 and strain TA2 produced hydroxamate siderophores, although the activity was greater in strain TA15. ECPs from both bacterial species at high concentrations, as well as viable bacteria, caused significant reductions in hemocyte survival after 4 h of incubation, whereas no significant differences in viability were observed during incubation with heat-killed bacteria.

Culture of carpet shell clams (Ruditapes decussatus) is a traditional activity that has great economical importance in Spain, particularly in Galicia (northwest region of Spain). Therefore, losses in production of this clam species would seriously affect the economy of this region.

Globally, clam production is often affected by vibriosis, which leads to high mortality rates mainly in nursery cultures of juvenile bivalves (20, 35). In Spain serious mass mortalities associated with Vibrio tapetis infections have been reported previously (15, 21). V. tapetis causes brown ring disease in Ruditapes species, which is characterized by the appearance of brown conchioline deposits that have variable distributions and variable thicknesses on the inner shell of diseased clams (41, 42).

Susceptibility of other cultured bivalve species to infections caused by bacteria belonging to the genus Vibrio has been found in several scallop species, including Aequipecten irradians (52), Euvola ziczac (22), Argopecten purpuratus (43, 44), Pecten maximus (36), and Argopecten ventricosus (45), in oyster species, including Crassostrea virginica (11) and Crassostrea gigas (53), and also in abalone (Haliotis diversicolor supertexta) (30).

In this paper, we report isolation of Vibrio splendidus biovar II and Vibrio alginolyticus as the causative agents of episodes of mass mortality of larvae and spat of carpet shell clams (R. decussatus) in a commercial hatchery. The histological lesions caused by infection of clams with both bacterial isolates are described. The general enzymatic activities of viable bacteria and their extracellular products (ECPs), as well as the in vitro influence on hemocyte survival, were determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolation.

Larvae and spat of naturally infected clams in a commercial hatchery were crushed in a sterile glass homogenizer and plated on tryptic soy agar with 1% NaCl (TSA-1) and on thiosulfate citrate bile sucrose agar (Difco). The most abundant colonies were selected and obtained in pure culture for characterization and identification. For long-term preservation bacteria were frozen in tryptic soy broth (Difco) supplemented with 1% NaCl and 15% glycerol.

Characterization of the bacterial isolates.

Pure cultures of the most abundant bacterial strains (strains TA2 and TA15) were subjected to standard morphological, physiological, and biochemical plate and tube tests by using the procedures described in Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (24) and the scheme of Alsina and Blanch (1). Gram staining (13), the oxidase test, morphology, motility, susceptibility to the vibriostatic compound O/129, and growth on thiosulfate citrate bile sucrose agar were the main assays employed to identify the organisms. In parallel, a commercial miniaturized API 20E kit (BioMérieux) was also used.

Drug resistance patterns of the bacterial isolates were determined by the disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid) supplemented with 1% NaCl. The following concentrations of antibiotics were used: ampicillin, 10 μg/disk; chloramphenicol, 30 μg/disk; nitrofurantoin, 300 μg/disk; oxolinic acid, 2 μg/disk; oxytetracycline, 30 μg/disk; streptomycin, 10 μg/disk; tetracycline, 30 μg/disk; and trimethroprim-sulfamethoxazole, 25 μg/disk.

DNA of both bacterial strains was isolated by conventional procedures, and a 312-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified by using forward primer PSL (5′-AGGATTAGATACCCTGGTAGTCCA-3′) and reverse primer PSR (5′-ACTTAACCCAACATCTCACGACAC-3′), which hybridized to conserved regions of the 16S rRNA gene corresponding to positions 782 and 1094 of Escherichia coli, respectively (14). Direct sequencing of purified PCR products was accomplished by using a BigDye terminator cycle sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's directions and an ABI PRISM 377 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Bacterial sequences were subjected to BLAST searches (2) by using the National Center for Biotechnology Information GenBank database.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Bacterial small-subunit rRNA sequences were aligned with other Vibrio sequences by using the program ClustalW (51). Evolutionary relationships between the defined rRNA sequences were inferred by using the neighbor-joining method (46). The accuracy of the resulting tree was measured by bootstrap resampling of 1,000 replicates. The E. coli sequence was used as an outgroup.

Experimental infections.

In order to confirm the pathogenicity of bacterial strains TA2 and TA 15, which were isolated from infected spat and larvae in the commercial hatchery, experimental challenges were conducted with carpet shell clam spat that were approximately 6 mm long. Healthy spat of carpet shell clams obtained from a commercial hatchery were maintained in marine aquaria at 18°C with aeration and were fed daily with 1.5 × 105 cells of an algal mixture of Isochrysis galbana and Tetraselmis svecica (1:1) per ml. Both bacterial isolates were inoculated by intravalvar injection and by immersion in separate experiments.

Overnight cultures of the bacterial strains to be tested were washed by centrifugation and suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Dilutions of the resulting bacterial suspensions were spread on TSA-1 to determine the number of CFU per milliliter.

Experimental challenges by immersion were performed in flat-bottom, circular, 5-liter tanks at 18°C with gentle aeration. Spat were fed daily with the algal mixture described above, and the water in the tanks was partially (40%) changed every day. Groups of 100 clams were infected with each bacteria isolate (TA2 or TA15) by adding bacterial suspensions directly to the water to obtain a final bacterial concentration of 1 × 106 CFU/ml. A control tank with an identical experimental setup but without the pathogenic bacteria was also included. The mortality rate was determined by directly counting the surviving spat for 30 days postchallenge.

For intravalvar injection, clams were taken out of the water and placed on filter paper for approximately 20 min. After this, the bivalves were inoculated in the pallial cavity with 20 μl of a bacterial suspension (5 × 106 CFU/ml) or with an equal volume of PBS as a control by using an insulin syringe. Once the infection procedure was performed, the bivalves were kept out the water for 30 min before they were placed back into the tanks.

To verify Koch's postulate (10) in these experiments, the challenged clams were sampled to reisolate and identify the bacterial pathogen. In all cases, mortality was attributed to the bacterium inoculated if it was recovered in pure culture from gaping or dead clams.

Histopathological examination.

Samples of infected carpet shell clams (larvae and spat) from the commercial hatchery, as well as from experimental challenges, were fixed with Davidson's fixative (48) for 24 h. Whole larvae or the whole bodies of the juveniles were then processed manually (in the case of larvae) or by using an automatic tissue processor (Reichert-Jung Histokinette 2000) (in the case of juveniles) and embedded in paraffin, and sections were cut with a microtome (Reichert-Jung Ultracut). The sections (5 μm) were first deparaffinized and rehydratated, and then they were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain and Giemsa stain for histopathological examination with a microscope (Nikon Optiphot).

Preparation of the bacterial extracellular products.

The bacterial ECPs were obtained by the cellophane plate technique (29) by spreading 0.1 ml of a 24-h culture in tryptic soy broth with 1% NaCl over sterilized cellophane sheets placed on TSA-1 plates. The plates were incubated for 24 h, and the cells were washed off the cellophane with PBS. The suspensions were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size membranes and stored at −80°C until they were used. The protein concentrations of the ECPs were evaluated by the method of Bradford (9) with the Bio-Rad reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany).

The general enzymatic activities of bacterial strains TA2 and TA15, as well as nontreated ECPs or heat-treated ECPs (100°C for 10 min), were evaluated by using the API ZYM system (BioMérieux) incubated at 22°C for 24 h.

Growth under iron-limiting conditions and siderophore production.

Both strains were cultured in M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) Casamino Acids (CM9 medium) supplemented with 10 μM nonassimilable iron chelator 2,2′-dipyrydil (Sigma), which makes iron unavailable to bacteria if they do not possess a high-affinity iron uptake system. The MIC of 2,2′-dipyrydil was determined in CM9 medium tubes containing increasing concentrations of the chelator and was defined as the lowest concentration at which no bacterial growth was observed.

The production of compounds with siderophore activity was investigated in CAS agar (47). Overnight cultures in CM9 medium were spotted on CAS agar plates, which were incubated for 48 h at 25°C. Results were considered positive when orange halos appeared around spots. The size of the halo was used as a way to estimate the siderophore level produced. The CAS liquid assay was also performed with both strains. Production of phenolic compounds was detected in cell-free supernatants obtained from iron-depleted cultures in CM9 medium supplemented with 10 μM 2,2′-dipyrydil by using the colorimetric test of Arnow (5). Hydroxamic acids were determined by a modification of the Csáky method (4).

Clam hemolymph.

Adult carpet shell clams were obtained from the Ría de Vigo (northwest Spain). They were maintained in filtered seawater tanks at 15°C with aeration and were fed daily with the mixture of I. galbana and T. svecica (1:1). Clam shells were notched with a grinding machine near the adductor muscle, and 1 ml of hemolymph was withdrawn from each individual from the adductor muscle with a disposable syringe. Hemolymph extracted from 10 animals was pooled to perform the experiments.

Viability of hemocytes.

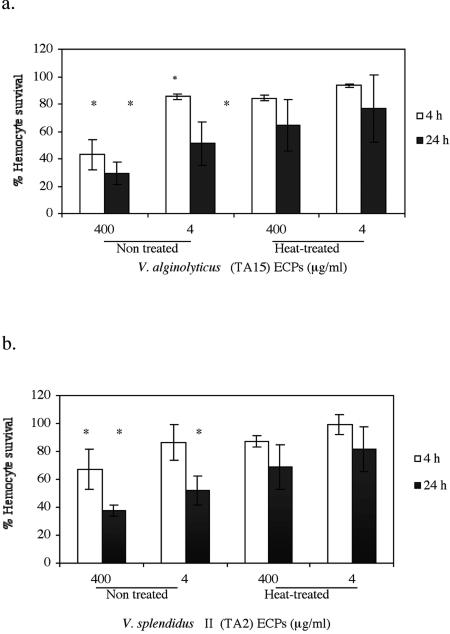

Clam hemocytes were placed in sterile tubes and treated with viable or heat-killed (100°C, 2 h) bacteria at a dose of 5 × 106 bacteria/ml and also with nontreated and heat-treated (100°C for 10 min) bacterial ECPs (400 and 4 μg/μl). After 4 and 24 h of incubation, aliquots were removed, and cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. All treatments were performed in triplicate for each of the three hemolymph pools. The data were expressed as percentages of viable cells based on the initial cell number.

Statistics.

The data were compared by using a Student t test. The results were expressed as means ± standard deviations, and differences were considered statistically significant at a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Characterization of the bacterial isolates.

Two episodes of mortality of cultured carpet shell clams (R. decussatus) were recorded in a commercial hatchery located in Spain. A clam larva mortality rate of 62% was observed in the first disease outbreak, and V. alginolyticus was isolated as the predominant organism from moribund larvae. In the second outbreak, the rate of clam larva mortality was 73%, and both V. alginolyticus and V. splendidus were isolated as predominant organisms from moribund animals. These bacteria were also isolated from moribund spat. The bacterial strains were isolated, maintained in pure culture, and identified as V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 and V. alginolyticus strain TA15 by using the biochemical and physiological characteristics shown in Table 1 (mainly swarming, Voges-Proskauer, arginine dihydrolase, ornithine decarboxylase, and lysine decarboxylase characteristics).

TABLE 1.

Main phenotypic characteristics of the pathogenic bacterial V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 and V. alginolyticus TA15 isolated from diseased clams (R. decussatus) in a commercial hatcherya

| Test | V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 | V. alginolyticus TA15 |

|---|---|---|

| Gram stain | − | − |

| Motility | + | + |

| Oxidase | + | + |

| Catalase | + | + |

| Swarming on solid media | − | + |

| Pigment | − | − |

| Thiosulfate citrate bile sucrose | + | + |

| Indole | + | + |

| Voges-Proskauer | − | + |

| H2S production | − | − |

| O/F Glucose | F | F |

| Gas from d-Glucose | − | − |

| Growth at 40°C | − | + |

| Na+ required for growth | + | + |

| Arginine dihydrolase | − | − |

| Ornithine decarboxylase | − | + |

| Lysine decarboxylase | − | + |

| β-Galactosidase (ONPG) | − | − |

| Acid production from sucrose | − | + |

| Gelatinase | + | + |

| Amylase | + | + |

| Reduction of NO3 to NO2 | + | + |

| Resistance or sensitivity to: | ||

| O/129 | S | S |

| Ampicillin | I | R |

| Chloramphenicol | S | S |

| Nitrofurantoin | I | S |

| Oxolinic acid | S | S |

| Oxytetracycline | S | I |

| Streptomycin | I | S |

| Tetracycline | I | R |

| Trimethropim-sulfamethoxazole | S | R |

Abbreviations: F, fermentative; R, resistant; S, sensitive; I, intermediate; O/F, oxidation-fermentation; ONPG, o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside.

Both bacterial strains were sensitive to chloramphenicol and oxolinic acid. V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 was also very sensitive to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, whereas V. alginolyticus strain TA15 appeared to be resistant.

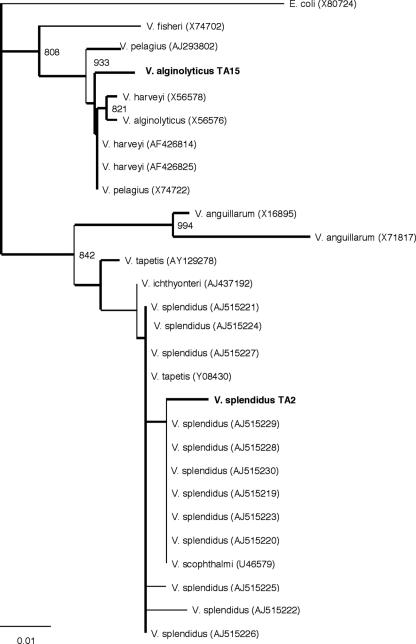

The sequences of the conserved fragment of the 16S rRNA gene amplified by PCR were used for BLAST homology searches, and the results of the identification of the bacterial strains were in agreement with the results obtained by traditional techniques. The V. splendidus TA2 sequence (accession number A4353085) appeared to be related to V. splendidus strains with an E value of e-139. V. alginolyticus TA15 (accession number A4353084) was similar to several Vibrio strains, including strains of V. alginolyticus (E value, e-130). The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), which was constructed mainly with sequences from Vibrio strains isolated from fish and shellfish (GenBank accession numbers are indicated in Fig. 1), clearly separated one group containing Vibrio pelagius (or Listonella pelagia), Vibrio alginolyticus, Vibrio harveyi, and Vibrio fisheri strains, including V. alginolyticus TA15, and another group containing the Vibrio anguillarum subgroup and a subgroup consisting of mainly V. splendidus strains, including V. splendidus TA2.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree for clam bacterial strains and different Vibrio sequences (GenBank accession numbers are indicated in parentheses) derived from a conserved fragment of the 16S rRNA gene. The numbers at the nodes indicate the levels of bootstrap support based on 1,000 replicates (values less than 750 are not shown). Bar = 1% sequence divergence.

Experimental infections.

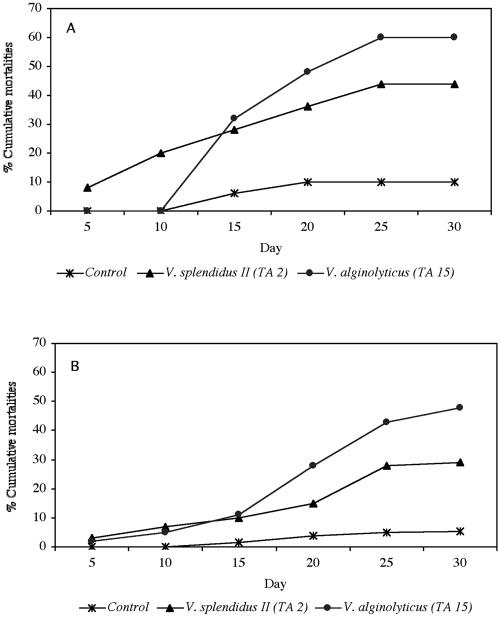

Experimental challenges demonstrated that both V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 and V. alginolyticus TA15 were able to induce significant mortality in carpet shell clam spat. In addition, it was found that both routes of experimental infection were effective in inducing clam mortality (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Cumulative clam mortalities caused by intravalvar (A) and immersion (B) experimental infections with V. splendidus biovar II and V. alginolyticus recorded daily for 30 days. One hundred clams per treatment were used.

V. alginolyticus TA15 seemed to be more virulent than V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2, since it produced higher mortality rates at the end of the intravalvar infection and immersion challenge experiments (60 and 48%, respectively). It is important to point out that intravalvar injection was the most effective route of infection (Fig. 2A). Experimental infection by immersion resulted in a final cumulative level of mortality which was lower than that obtained by intravalvar injection (Fig. 2B).

Bacteriological studies showed that both bacterial strains were reisolated from dead infected clams as pure cultures.

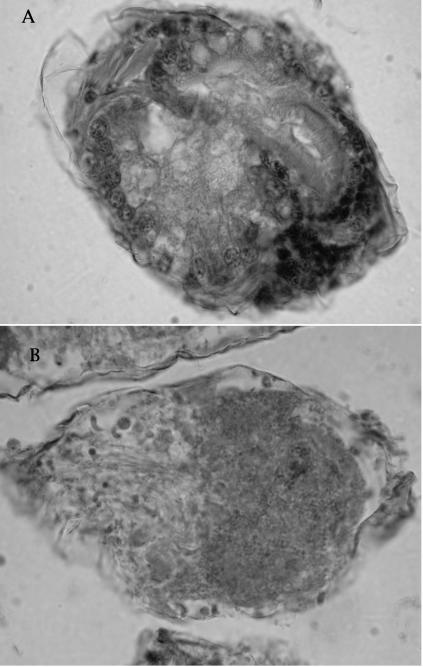

Histopathological examination.

A number of lesions were observed in carpet shell clams obtained from the commercial hatchery in which there was a high mortality rate. In moribund larvae there was an association of bacillary bacteria with the velum that caused a loss of velar cells. Histological examination revealed the presence of bacillary bacteria in the velum and advanced infection with necrosis in the clam tissue (Fig. 3). A pale color of the digestive tract in the affected larvae, probably caused by a decrease in feeding activity, was also observed.

FIG. 3.

Photomicrographs of a carpet shell clam control larva (A) and an infected larva showing necrosis and disorganization of the clam tissue (B) (hematoxylin and eosin staining). (B) Magnification, ×400.

Bacillary bacteria were also detected along the mantle folds of experimentally infected spat. Disorganization of muscles fibers and strong hemocytic infiltration, especially in the connective tissue, were also observed.

The histological lesions observed in the experimentally challenged spat were similar for both bacterial strains and both infection routes. No histological lesions were observed in noninfected control clams.

Enzymatic activity.

The ECPs of V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2, obtained by the cellophane plate technique, had general enzymatic activity similar to that of the whole viable cells (Table 2). The most important activities were alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase. When the ECPs were heat treated, the activities of most enzymes disappeared, and only a weak acid phosphatase reaction was detected.

TABLE 2.

Results of the API ZYM assay of V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 and V. alginolyticus TA15

| Strain | Enzyme | Enzymatic activitya

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viable bacteria | ECPs | Heat-treated ECPs (100°C, 10 min) | ||

| TA2 | Alkaline phosphatase | Very strong | Very strong | ND |

| Esterase (C4) | Strong | Strong | ND | |

| Esterase-lipase (C8) | Moderate | Strong | ND | |

| Leucine arylamidase | Moderate | Strong | ND | |

| Valine arylamidase | Low | Low | ND | |

| Cystine arylamidase | Weak | Weak | ND | |

| Trypsin | Moderate | Moderate | ND | |

| α-Chymotrypsin | Weak | Weak | ND | |

| Acid phosphatase | Very strong | Very strong | Weak | |

| N-Acetyl-β-glucos- aminidase | Moderate | Moderate | ND | |

| TA15 | Alkaline phosphatase | Very strong | Very strong | ND |

| Esterase (C4) | Moderate | Moderate | Low | |

| Esterase-lipase (C8) | Moderate | Moderate | Low | |

| Leucine arylamidase | Strong | Strong | ND | |

| Valine arylamidase | Moderate | Weak | ND | |

| Cystine arylamidase | Moderate | Weak | ND | |

| Trypsin | Strong | Strong | ND | |

| α-Chymotrypsin | Weak | Weak | ND | |

| Acid phosphatase | Very strong | Very strong | Very strong | |

| N-Acetyl-β-glucos- aminidase | Very strong | Moderate | ND | |

Very strong, ≥40 nmol of substrate hydrolyzed; strong, 30 nmol of substrate hydrolyzed; moderate, 20 nmol of substrate hydrolyzed; low, 10 nmol of substrate hydrolyzed; weak, 5 nmol of substrate hydrolyzed; ND, not detected.

For V. alginolyticus TA15, the activities of 10 enzymes were detected in viable cells, as well as in the bacterial ECPs (Table 2). The strongest enzymatic reactions were the alkaline phosphatase, acid phosphatase, and N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase reactions. Heat treatment of the bacterial ECPs resulted in low (10 nmol) esterase (C4) and esterase-lipase (C8) enzymatic activities and very strong (≥40 nmol) acid phosphatase enzymatic activity.

Growth under iron-limiting conditions and siderophore production.

To evaluate the ability of strains TA15 and TA2 to grow in low-iron environments, the MICs of 2,2′-dipyrydil were determined. Both strains were able to grow in CM9 minimal medium supplemented with 10 μM 2,2′-dipyrydil. However, for strain TA15, which was identified as V. alginolyticus, the MIC of 2,2′-dipyrydil was 80 μM, whereas for strain TA2, which was identified as V. splendidus, the MIC was 40 μM. The CAS method was used to evaluate the production of siderophores by both strains. When the strains were inoculated onto CAS agar plates, only strain TA15 grew normally and produced huge orange halos around growing spots; the ratio of the halo to the colonial growth was around 2.5. This indicated that there was strong production of compounds with siderophore activity. By contrast, strain TA2 did not grow in this medium after 48 h of incubation. The liquid CAS medium assay with cell-free supernatants gave positive results for both strains, although the reaction for the strain TA15 supernatant was stronger than the reaction for the strain TA2 supernatant. The cell-free supernatants from CM9 medium supplemented with 10 μM 2,2′-dipyrydil were also examined by using the Arnow and Csáky tests for the presence of catechols and hydroxamates. Both strains gave negative results for catechol production, whereas both strains were positive in the Csáky test, indicating that there was hydroxamate production.

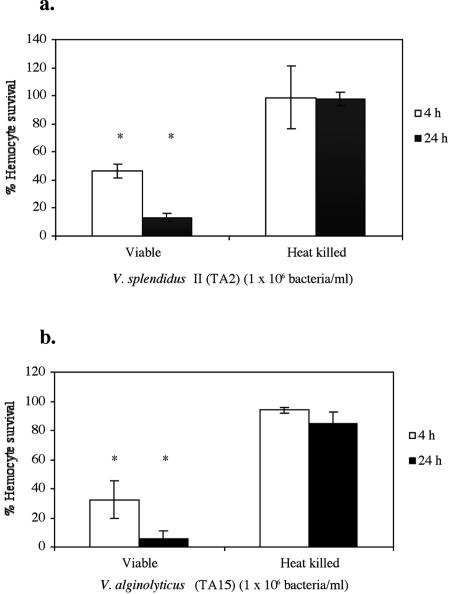

Viability of hemocytes.

The viability of clam hemocytes was significantly affected by incubation with both bacterial isolates. After 4 and 24 h of incubation with V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 and V. alginolyticus TA15, viable bacterial cells significantly decreased the viability of hemocytes. Heat-killed bacteria did not have a significant effect on clam hemocyte viability after 4 or 24 h of incubation (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Viability of clam hemocytes incubated for 4 and 24 h at 18°C with viable and heat-killed V. splendidus biovar II (a) and V. alginolyticus (b) at a concentration of 1 × 106 bacteria/ml. The data are expressed as means ± standard deviations and are percentages of viable hemocytes based on the initial cell count. An asterisk indicates that the level of viability was significantly lower than the mean level of viability of noninfected controls (P < 0.05). Three hemolymph pools were used in the experiment.

Incubation of hemocytes with the ECPs of both isolated bacteria significantly affected the viability of clam hemocytes. High doses of ECPs of V. alginolyticus TA15 significantly reduced the viability of hemocytes after 4 and 24 h of incubation (Fig. 5a). In the case of the ECPs of V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2, only after 24 h of incubation was a significant reduction in hemocyte survival observed (Fig. 5b). When ECPs of both bacterial isolates were heat treated (100°C for 10 min), no significant reduction in hemocyte survival was observed for any incubation time (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Viability of clam hemocytes incubated for 4 and 24 h at 18°C with the ECPs and heat-treated (100°C, 10 min) ECPs of V. alginolyticus (a) and V. splendidus biovar II (b) at concentrations of 4 and 400 μg/ml. The data are expressed as means ± standard deviations and are percentages of viable hemocytes based on the initial cell count. An asterisk indicates that the level of viability was significantly lower than the mean level of viability of noninfected controls (P < 0.05). Three hemolymph pools were used in the experiment.

DISCUSSION

The Vibrio taxa that are commonly associated with cultured bivalves are V. anguillarum, V. tubiashii, V. alginolyticus, and V. splendidus biovar II (8, 18, 31, 50). These Vibrio taxa are virulent mainly during the bivalve larval stages due to their ability to produce exotoxins (19, 38, 43) or their ability to invade larval tissues directly, causing necrosis.

The results obtained in the present work confirm the pathogenic effects of two Vibrio species that were the causative agents of high rates of mortality of larvae and carpet shell clam spat in a commercial hatchery. To our knowledge, this is the fist time that these bacterial species have been associated with mortality of larvae and juvenile carpet shell clams. The bacteria were classified by using both traditional biochemical and morphological methods and also molecular techniques. Although the amplified sequence of the 16S rRNA gene was quite conserved, the bacterial identities determined by homology searches and by using the phylogenetic tree generated were in agreement with the bacterial identities obtained by traditional techniques. However, more detailed taxonomic positions of the bacterial isolates may be obtained by using the complete sequence of the 16S rRNA gene; that was not the aim of this work.

In the experimental challenges, V. alginolyticus TA15 appeared to be more virulent than V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2. V. alginolyticus strains are often isolated from episodes of mortality of cultured marine bivalves. Although this bacterial species may not be a very strongly invasive bacterium, its pathogenicity may rely on extracellular toxin production, as documented in other investigations (7, 12, 38, 39, 49). Nottage and Birkbeck (37) purified a low-molecular-weight ciliostatic toxin from a V. alginolyticus strain, and this toxin can cause undesirable effects in the physiology of infected clams, such as inhibition of filtration and thus feeding (34). Furthermore, it has been proved that virulent Vibrio strains have a cytotoxic effect, the ability to kill hemocytes, that seems to be mediated by intact bacterial cells, as well as by extracellular factors (27, 28, 39).

Although V. splendidus has been present in environmental samples of marine water and shellfish species (16, 32), it has also been mentioned as the causative agent of juvenile oyster (C. gigas) mortality (25), as well as C. virginica mortality (50). Mortality of cultured scallops (P. maximus) and mortality of Pacific oysters (C. gigas) in France (26, 53) have been also associated with V. splendidus biovar II infections. However, the involvement of extracellular toxins in the pathogenicity of V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 has not been studied. Our results indicate that the ECPs of V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2 and V. alginolyticus TA15 have cytotoxic activity that can significantly diminish clam hemocyte survival after 24 h of incubation, demonstrating that ECPs of both isolates are involved in the pathogenesis of the bacteria. The almost complete loss of enzymatic activity and cytotoxic activity of both bacterial ECPs after heat treatment (100°C for 10 min) suggests that the toxin is thermolabile. As observed for several isolates of Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida (33), the reduction in biological activity after heat treatment suggests that toxicity is not solely associated with the lipopolysaccharide content of the ECPs.

Hydroxamate production by other Vibrio species and its relationship with virulence have been reported previously (3, 6, 17, 40). The results described above indicate that hydroxamate siderophores are produced by strains TA15 and TA2, although the activity is stronger in strain TA15. The production of hydroxamate siderophores by V. alginolyticus or V. splendidus has not been described previously. The stronger siderophore activity detected in strain TA15 could explain in part the greater virulence of this strain.

The histological lesions caused by both inoculated bacteria, V. alginolyticus TA15 and V. splendidus biovar II strain TA2, resembled those previously described for larval vibriosis and bacillary necrosis reported for larval stages of oysters (50, 52) and cockle (Fulvia mutica) (23).

Both bacterial isolates were sensitive to most of the antibiotics tested in vitro. The mortality rates decreased when carpet sell clam larvae and spat stocks were treated with chloramphenicol and with nitrofurantoin in the commercial hatchery. However, development of alternative methods, such as probiotics, to control bacterial infections could prove to be useful in aquaculture since the prolonged use of antibiotics may result in selection of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by project FAIR-CT98-4334 funded by the European Union and by project PGIDT 01MAR 40203PR funded by Xunta de Galicia, Spain.

We thank Alicia Toranzo of the Department of Microbiology of the University of Santiago de Compostela for her cooperation in the bacteriological characterization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alsina, M., and A. Blanch. 1994. Improvement and update of a set of keys for biochemical identification of Vibrio species. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 77:719-721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaro, C., R. Aznar, E. Alcaide, and M. L. Lemos. 1990. Iron-binding compounds and related outer membrane proteins in Vibrio cholerae non-O1 strains from aquatic environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:2410-2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrus, C. R., M. A. Walter, J. H. Crosa, and S. M. Payne. 1983. Synthesis of siderophores by pathogenic Vibrio species. Curr. Microbiol. 9:209-214. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnow, L. E. 1937. Colorimetric determination of the components of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine-tyrosine mixtures. J. Biol. Chem. 118:531-541. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biosca, E. G., B. Fouz, E. Alcaide, and C. Amaro. 1996. Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition mechanisms in Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:928-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkbeck, T. H., and S. Gallacher. 1993. Interaction of the pathogenic vibrios with marine bivalves, p. 221-226. In R. Guerrero and C. Pedrós-Alió (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology. Spanish Society for Microbiology, Barcelona, Spain.

- 8.Bower, S. M., S. E. McGladdery, and I. M. Price. 1994. Synopsis of infectious diseases and parasites of commercially exploited shellfish. Annu. Rev. Fish Dis. 4:1-199. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brock, T. D., M. T. Madigan, J. M. Martinko, and J. Parker. 1994. Biology of microorganisms. Prentice-Hall International, London, United Kingdom.

- 11.Brown, C. 1973. The effects of some selected bacteria on embryos of the American oyster, Crassostrea virginica. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 21:245-253. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, C., and G. Roland. 1984. Characterization of exotoxin produced by a shellfish-pathogenic Vibrio sp. J. Fish Dis. 7:117-126. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buck, I. D. 1982. Nonstaining (KOH) method for determination of Gram reactions of marine bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 44:992-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell, P. W., III, J. A. Phillips III, G. J. Heidecker, M. R. Krishnamani, R. Zahorchak, and T. L. Stull. 1995. Detection of Pseudomonas (Burkholderia) cepacia using PCR. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 20:44-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro, D., E. Martínez-Manzanares, A. Luque, B. Fouz, M. A. Moriñigo, J. J. Borrego, and A. E. Toranzo. 1992. Characterization of strains related to brown ring disease outbreaks in southwestern Spain. Dis. Aquat. Org. 14:229-236. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro, D., M. J. Pujalte, L. Lopez-Cortes, E. Garay, and J. J. Borrego. 2002. Vibrios isolated from the cultured manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum): numerical taxonomy and antibacterial activities. J. Appl. Microbiol. 93:438-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colquhoun, D. J., and H. Sorum. 2001. Temperature dependent siderophore production in Vibrio salmonicida. Microb. Pathog. 31:213-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiSalvo, L. H., J. Blecka, and R. Zebal. 1978. Vibrio anguillarum and larval mortality in a California coastal shellfish hatchery. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 35:219-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elston, R., and L. Leibovitz. 1980. Pathogenesis of experimental vibriosis in larval American oyster, Crassostrea virginica. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 37:964-978. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elston, R., A. Gee, and R. P. Herwing. 2000. Bacterial pathogens and their control in bivalve spat culture. National Shellfisheries Association, Seattle, Wash.

- 21.Figueras, A., J. A. Robledo, and B. Novoa. 1996. Brown ring disease and parasites in clams (Ruditapes decussatus and R. phlippinarum) from Spain and Portugal. J. Shellfish Res. 15:363-368. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freites, L., C. Lodeiros, A. Vélez, and A. J. Bastardo. 1993. Vibriosis en larvas de vieira tropical Euvola (Pecten) ziczac (L). Caribb. J. Sci. 29:89-98. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujiwara, M., Y. Ueno, and A. Iwao. 1993. A Vibrio sp. associated with mortalities in cockle larvae Fulvia mutica (Mollusca: Cardiidae). Fish Pathol. 28:83-89. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieg, N. R., and J. G. Holt (ed.). 1984. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, vol. 1. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 25.Lacoste, A., F. Jalabert, S. Malham, A. Cueff, F. Gélébart, C. Cordevant, M. Lange, and S. A. Pulet. 2001. A Vibrio splendidus strain is associated with summer mortality of juvenile oysters Crassostrea gigas in the Bay of Morlaix (North Brittany, France). Dis. Aquat. Org. 46:139-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambert, C., J. L. Nicolas, V. Cila, and S. Corre. 1999. Vibrio splendidus related strain isolated from brown deposit in scallop (Pecten maximus) cultured in Brittany (France). Bull. Eur. Assoc. Fish Pathol. 19:102-106. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lane, E., and T. H. Birkbeck. 1999. Toxicity of bacteria towards haemocytes of Mytilus edulis. Aquat. Living Resour. 12:343-350. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lane, E., and T. H. Birkbeck. 2000. Species specificity of some bacterial pathogens of bivalve molluscs is correlated with their interaction with bivalve haemocytes. J. Fish Dis. 23:275-279. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, P. V. 1957. Survey of hemolysin production among species of Pseudomonas. J. Bacteriol. 74:718-727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu, P. C., Y. C. Chen, and K. K. Lee. 2001. Pathogenicity of Vibrio alginolyticus isolated from diseased small abalone Haliotis diversicolor supertexta. Microbios 104:71-77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lodeiros, C., J. Bolinches, C. Dopazo, and A. Toranzo. 1987. Bacillary necrosis in hatcheries of Ostrea edulis in Spain. Aquaculture 65:15-29. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macian, M. C., E. Garay, F. Gonzalez-Candelas, M. J Pujalte, and R. Aznar. 2000. Ribotyping of Vibrio populations associated with cultured oysters (Ostrea edulis). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 23:409-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magariños, B., Y. Santos, J. L. Romalde, C. Rivas, J. L. Barja, and A. E. Toranzo. 1992. Pathogenic activities of live cells and extracellular products of the fish pathogen Pasteurela piscicida. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:491-2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McHenery, J. G., and T. H. Birkbeck. 1986. Inhibition of filtration in Mytilus edulis L. by marine vibrios. J. Fish Dis. 9:256-261. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicolas, J. L., D. Ansquer, and J. C. Cochard. 1992. Isolation and characterization of a pathogenic bacterium specific to Manila clam Tapes philippinarum larvae. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2:153-159. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicolas, J. L., S. Corre, G. Gauthier, R. Robert, and D. Ansquer. 1996. Bacterial problems associated with scallop Pecten maximus larval culture. Dis. Aquat. Org. 27:67-76. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nottage, A. S., and T. H. Birkbeck. 1986. Toxicity of marine bivalves of culture supernatant fluids of the bivalve-pathogenic Vibrio strain NCMB 1338 and other marine vibrios. J. Fish Dis. 9:249-256. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nottage, A. S., and T. H. Birkbeck. 1987. The role of toxins in Vibrio infections of bivalve mollusca. Aquaculture 67:244-246. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nottage, A. S., and T. H. Birkbeck. 1990. Interactions between different strains of V. alginolyticus and hemolymph fractions from adult Mytilus edulis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 56:15-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okujo, N., and S. Yamamoto. 1994. Identification of the siderophores from Vibrio hollisae and Vibrio mimicus as aerobactin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 118:187-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paillard, C., and P. Maes. 1994. The brown ring disease symptom in the Manila clam, Ruditapes philippinarum and R. decussatus (Mollusca, Bivalvia). Dis. Aquat. Org. 15:93-197. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paillard, C., P. Maes, and R. Oubella. 1994. Brown ring disease in clams. Annu. Rev. Fish Dis. 4:219-240. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riquelme, C., G. Hayashida, A. E. Toranzo, J. Vilchis, and P. Chavez. 1995. Pathogenicity studies on a Vibrio anguillarum-related (VAR) strain causing an epizootic in Argopecten purpuratus larvae cultured in Chile. Dis. Aquat. Org. 22:135-176. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riquelme, C., A. E. Toranzo, J. L. Barja, N. Vergara, and R. Araya. 1996. Association of Aeromonas hydrophila and Vibrio alginolyticus with larval mortalities of scallop (Argopecten purpuratus). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 67:213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sainz, J. C., A. N. Maeda-Martinez, and F. Ascencio. 1999. Experimental vibriosis induction with Vibrio alginolyticus of larvae of catarina scallop (Argopecten ventricosus-circularis) (Sowerby II, 1984). Microb. Ecol. 35:188-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4:406-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwyn, B., and J. B. Neilands. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 160:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaw, B. L., and H. I. Battle. 1957. The gross microscopic anatomy of the digestive tract of Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin). Can. J. Zool. 35:325-346. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sinderman, C. 1990. Principal diseases of marine fish and shellfish, 2nd ed., vol. 2, p. 41-62. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sugumar, G., T. Nakai, Y. Hirata, D. Matsubra, and K. Muroga. 1998. Vibrio splendidus biovar II as the causative agent of bacillary necrosis of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas larvae. Dis. Aquat. Org. 33:11-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tubiash, H. S., P. E. Chanley, and E. Leifson. 1965. Bacillary necrosis disease of larval and juvenile bivalve molluscs. Etiology and epizootiology. J. Bacteriol. 90:1036-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waechter, M., F. Le Roux, J. L. Nicolas, E. Marissal, and F. Berthe. 2002. Characterization of pathogenic bacteria of the cupped oyster Crassostrea gigas. C. R. Biol. 325:231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]