Abstract

Mutations designated gtaC and gtaE that affect α-phosphoglucomutase activity required for interconversion of glucose 6-phosphate and α-glucose 1-phosphate were mapped to the Bacillus subtilis pgcA (yhxB) gene. Backcrossing of the two mutations into the 168 reference strain was accompanied by impaired α-phosphoglucomutase activity in the soluble cell extract fraction, altered colony and cell morphology, and resistance to phages φ29 and ρ11. Altered cell morphology, reversible by additional magnesium ions, may be correlated with a deficiency in the membrane glycolipid. The deficiency in biofilm formation in gtaC and gtaE mutants may be attributed to an inability to synthesize UDP-glucose, an important intermediate in a number of cell envelope biosynthetic processes.

Peptidoglycan and wall teichoic acids (WTAs) are major constituents of the cell wall in many gram-positive bacteria. It has been proposed that lipoteichoic acids (LTAs), polymers anchored in the membrane, and WTAs contribute to the cell wall electrolyte properties, modulate the activity of peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes, and maintain cation homeostasis (24). The biology of WTAs and LTAs has been reviewed recently (17, 24).

In Bacillus subtilis 168, poly(glycerolphosphate) [poly(Gro-P)], known as the major WTA, is glucosylated and d-alanylated at the C-2 position of the 1,3-phosphodiester-linked glycerol units (17, 24). Absence of either of these substituents does not affect cell viability, whereas the polymer backbone is an essential cell constituent (20). Glucosylation of poly(Gro-P) plays an essential role in the attachment of phage φ29 to B. subtilis 168 (34). Mutations associated with a φ29-resistant phenotype were mapped to three loci, gtaA, gtaB, and gtaC (35). Subsequently, analyses of gtaB-deficient mutants established that gtaB is the structural gene of the UTP:α-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (28, 31), the enzyme that catalyzes the formation of UDP-glucose (UDP-Glc) from α-glucose 1-phosphate (α-Glc 1-P) and UTP. gtaA (rodD), which has been renamed tagE, encodes the enzyme for the transfer of glucosyl groups from UDP-Glc to the poly(Gro-P) moiety of the major WTA (10, 19). In addition, UDP-Glc is required for the polymerization of poly(glucosyl N-acetylgalactosamine phosphate), the minor WTA (17), as well as for the YpfP-governed synthesis of diglucosyldiacylglycerol, the membrane anchor for poly(Gro-P) which forms the main chain of LTA (12).

Mutations leading to an α-phosphoglucomutase (α-PGM) deficiency (i.e., mutations associated with the inability to convert glucose 6-phosphate [Glc 6-P] to α-Glc 1-P) were mapped to the gtaC locus at 77° on the B. subtilis genome (1, 28). The gtaC mutants were, however, split into two subgroups; the PBSZ-sensitive mutants retained the designation gtaC, whereas the PBSZ-resistant mutants were renamed gtaE (28). Inspection of the B. subtilis 168 chromosome sequence (16) suggested that the α-PGM (EC 5.4.2.2) gene corresponds to yhxB, a 1,698-nucleotide open reading frame (encoding 565 amino acids) whose calculated map position is 85.9°.

In the present study we found that gtaC and gtaE mutations map to yhxB (designated pgcA in this paper). Below we present evidence that the α-PGM deficiency correlates with altered cell morphology and impaired biofilm formation. To further characterize this phenotype, strains bearing mutations in the biosynthetic pathway downstream of the α-Glc 1-P formation step were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, phages, and culture conditions.

B. subtilis strains are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli TOP10 [F− mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 deoR araD139 Δ(araA-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (Strr) endA1 nupG], which was used as a host strain for plasmid construction, and plasmid vector pCR2.1-TOPO were obtained from Invitrogen. Plasmid pMTL20EC has the backbone of pMTL21EC (25) but the inverted orientation of the EcoRI-HindIII polylinker.

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains used

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | 16 |

| W23 | 23 | |

| SL1020 | metB5 leuA8 thr-5 su3+ attSPβ | 6 |

| L6118 | hisA1 argC4 leuA8 ilvA1 gtaE151 | 28 |

| L6125 | hisA1 argC4 leuA8 ilvA1 gtaE158 | 28 |

| L6179 | hisA1 argC4 metC3 pyrA gtaC189 | 28 |

| L6188 | hisA1 argC4 metC3 pyrA gtaC198 | 28 |

| L6333 | purA16 metB5 ilvA1 tagE12a | 14 |

| L16114 | gtaB::p624 | This study |

| L16134 | gtaC189 | This study |

| L16135 | gtaE151 | This study |

| L16171 | ggaA::p690 | This study |

| L16172 | tagE12 | This study |

| L16176 | tagE12 ggaA::p690 | This study |

| L16177 | ypfP::p701 | This study |

tagE12 was previously designated gtaA12.

Phage φ29 and a spontaneous clear-plaque mutant of phage ρ11 (6) were obtained from laboratory stocks. Bacteria were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Difco) or on LB agar (Difco) plates, unless otherwise specified. For E. coli transformants, ampicillin was routinely used at a concentration of 50 μg/ml.

Plasmid construction.

The 1.1-kb DNA segment containing the gtaC189 mutation was amplified by PCR by using genomic DNA from strain L6179 and oligonucleotides BS449 and BS450. Cloning of the PCR products into pCR2.1-TOPO yielded plasmid p647. The segment containing the gtaE151 mutation was amplified by PCR by using strain L6118 DNA with oligonucleotides BS451 and BS452. Ligation of this 1-kb segment to pCR2.1-TOPO gave rise to plasmid p648.

Part of the ypfP gene was amplified by using primers VL590 and VL591. Amplified DNA was digested with EcoRI and HindIII to release the relevant 353-bp fragment that was cloned into EcoRI-HindIII-digested pMTL20EC, resulting in plasmid p701.

The segment of the gtaB gene (residues 46 to 420 with respect to the start codon) obtained by PCR amplification with oligonucleotides BS373 and BS374 was digested with BamHI-EcoRI and ligated to the corresponding cloning sites of pMTL20EC to obtain plasmid p624.

The 1,563-bp segment of strain L6333 extending over the 3′ part of the tagE gene and the 5′ part of tagF, which contained the tagE12 (gtaA12) mutation, was amplified with oligonucleotides BS521 and BS522. The amplified DNA was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, generating plasmid p692.

The 501-bp segment of the 5′-terminal part of ggaA was amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides BS508 and BS509. Cloning of the EcoRI-SphI digestion product into pMTL20EC resulted in plasmid p690.

Oligonucleotides.

The following oligonucleotides were used in this study: BS373 (5′-ACGGATCCACACGTTTTCTTCCGGCTACGAAAG-3′), BS374 (5′-ACGAATTCTGGAGTTTCAGCCTGAACAATATCG-3′), BS409 (5′-GATTCCAATGGGATGAGCAGGCGAA-3′), BS410 (5′-TTCTCACTCCGGCATTGATCTTGTA-3′), BS449 (5′-AGTGACAGAGGCACCCGCTTCATA-3′), BS450 (5′-GAACAACACCGTTATCAGGCAGGA-3′), BS451 (5′-TTCACACCGCTGCATGGAACTGCA-3′), BS452 (5′-CTTTTCACTGTCTTCCAAAGATGA-3′), BS521 (5′-CGGAACTGCGTCAATATTGGATAGA-3′), BS522 (5′-TCCGTTCCTGAACGTCTCTCTTTCA-3′), VL508 (5′-ACAGAATTCTGATGGTAGTGTTGACAGCAGTCC-3′), VL509 (5′-ACAGCATGCTACTTTCCTTCTGCAACTGCTCCG-3′), VL590 (5′-TGACTGCAAATTACGGAAATGGACA-3′), and VL591 (5′-GCGGTCATCATTTCTGATTCCTTCA-3′).

Susceptibility to phages.

A ρ11 stock was prepared by addition of phage at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 to 0.5 to a culture of B. subtilis SL1020 growing at 37°C at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3 in LB medium supplemented with 0.1% glucose, 5 mM CaCl2, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM MnCl2. After massive lysis, which began about 1 h after infection, cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min), and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter and stored at 4°C. A φ29 stock was obtained in a similar manner. However, the LB medium was not supplemented, and the multiplicity of infection was 1 to 5.

An overnight culture of the PBSZ-lysogenic B. subtilis strain W23 was diluted to an OD600 of 0.01 in SA medium (13) and incubated with aeration at 37°C until the OD600 was 0.3. Mitomycin C was added to a final concentration of 2 μg/ml, and incubation was continued for 10 min. Cells were harvested by filtration with a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter, washed with SA medium, resuspended in fresh prewarmed SA medium, and incubated at 37°C until lysis was visible. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation (3,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), and the PBSZ-containing supernatant was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter and stored at 4°C.

Phage stocks were spotted onto fresh streaks of appropriate B. subtilis strains on LB agar plates and incubated for 16 h at 30°C. Growth inhibition and lysis revealed sensitivity to phages, whereas resistance was indicated by the absence of a zone of clearing.

Construction of B. subtilis mutants.

B. subtilis competent cells were prepared by the method of Karamata and Gross (13). For backcrossing the gtaC189, gtaE151, and tagE12 mutations, strain 168 cells were transformed with approximately 1 ng of pTRP-H3 (2) together with 2.5 μg of p647 (gtaC189), p648 (gtaE151), or p692 (tagE12). Plating on TS agar (13) without tryptophan allowed selection of Trp+ recombinants. In crosses with pTRP-H3/p647 and pTRP-H3/p648 a fraction of Trp+ transformants acquired resistance to ρ11 and φ29. Similarly, pTRP-H3/p692 cotransformation yielded a fraction of φ29-resistant Trp+ recombinants. Control PCRs (data not shown) confirmed that mutation transfer occurred by double crossover and not by plasmid integration.

For inactivation of ggaA and ypfP, competent cells were transformed with plasmids p690 and p701, each containing an internal fragment of the corresponding gene. Transformants were selected on LB agar plates containing 4 μg of chloramphenicol per ml. Correct plasmid integration was verified by PCR (data not shown).

DNA methods.

B. subtilis genomic DNA was isolated with the QIAGEN Genomic-tip system (QIAGEN). Plasmid DNA was prepared by the alkaline lysis method (30).

DNA sequences were determined by primer walking. Sequencing was carried out by Microsynth (Balgach, Switzerland). The sequence of the pgcA region of strains 168, L6179 (gtaC189), L6188 (gtaC198), L6118 (gtaE151), and L6125 (gtaE158) was determined from PCR products generated with oligonucleotides BS409 and BS410.

PCRs were carried out with a Taq PCR Master Mix kit (QIAGEN) by using 1 ng of B. subtilis genomic DNA and 20 pmol of each primer. The PCR involved 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 47°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min per kb amplified.

Biofilm formation assay.

B. subtilis was grown in LB medium adjusted to pH 7 and supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 and 0.1% glucose (8). Exponentially growing cultures (OD600, 0.3) were diluted to an OD600 of 0.01, and 100-μl aliquots of the freshly inoculated medium were dispensed into wells of a 96-well polyvinyl chloride microtiter plate (Falcon 353911 flexible U-bottom plates available from Becton-Dickinson Labware), which was incubated at 30°C for 70 h without shaking. Unbound cells were removed by gentle aspiration, after which the remaining, adherent cells were heated for 20 min at 70°C (7) and stained by addition of 150 μl of 0.5% safranin for 5 min. As revealed by an initial experiment with B. subtilis strain 168, fixation by heat reduced the possible loss of the loosely attached pellicle in subsequent steps. Therefore, heat fixation was performed in all experiments. The wells were rinsed with water five times. The safranin that stained adherent cells was solubilized in 150 μl of ethanol-0.1 M sodium citrate (1:1, vol/vol) (pH 4). Biofilm formation was quantified by measuring the A492 with a Multiskan RC plate reader (Thermolabsystems, Helsinki, Finland). Each strain was assayed three to five times in 20 to 24 wells. The average values from independent assays were averaged to determine the level of biofilm formation.

Cell extract preparation.

Bacteria were grown at 37°C in 250 ml of TS medium supplemented with 5 mM MgSO4 and 20 μg of tryptophan per ml. At an OD600 of 0.9, cells were recovered by centrifugation for 10 min at 7,000 × g and 4°C. Subsequent steps were carried out on ice or at 4°C by using ice-cold solutions. The pellets were rinsed with distilled water and resuspended in 5 ml of 100 mM triethanolamine (TEA) containing 5 mM MgCl2 and 2.2 mM EDTA. The cells were disrupted by 5-s bursts of sonication that were repeated 10 times at 55-s intervals. The cell debris and unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation for 15 min at 15,000 × g. The supernatant was frozen at −70°C and used as a source of enzyme. The protein concentrations of cell extracts were determined with the BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.)

α-PGM assay.

α-PGM activity was assayed by determining the rate of conversion of α-Glc 1-P to Glc 6-P in a coupled reaction with Glc 6-P dehydrogenase, which was monitored in terms of NADPH formation. The reaction mixture contained cell extract (0.1 mg of protein), 0.6 mM β-NADP, and 1 U of Glc 6-P dehydrogenase (Sigma) in 1 ml (total volume) of 100 mM TEA containing 5 mM MgCl2 and 2.2 mM EDTA. The reaction was started by adding 1.5 μM α-d-Glc 1-P. The increase in A340 at room temperature was measured spectrophotometrically (Novaspec II; Pharmacia Biotech). The specific activity was expressed in nanomoles of substrate converted into product per minute per milligram of total protein. Control assays in which the mixtures lacked NADP, Glc 1-P, or cell extract were also carried out.

Fractionation of [2-3H]glycerol-labeled cells.

Cells aerated by bubbling were grown at 37°C in SA medium supplemented with 20 μg of tryptophan per ml, 5 mM glycerol, and 1.5 mM MgCl2. At an OD600 of 0.3, samples were diluted in fresh medium to an OD600 of 0.01. [2-3H]glycerol (Amersham) was added at a final concentration of 1 μCi/ml (37 kBq/ml), and incubation was continued until the OD600 was 0.320. To determine the incorporation of radioactive glycerol into the cell wall fraction, 2-ml samples were washed and resuspended in TMS-lysozyme buffer (1 M sucrose, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 8 mM MgCl2, 200 μg of lysozyme per ml). After conversion of over 95% of the cells into protoplasts, which occurred after 75 min of incubation at 37°C, the suspension was fractionated (26) in order to determine the amounts of the glycerol label in phospholipids, WTA, and LTA. The amounts of radioactivity in the phospholipids, WTA, and LTA were expressed as the fractions of total glycerol incorporated into the three relevant fractions.

Microscope observations.

A colony grown overnight on LB agar at 37°C was suspended in 15 ml of LB medium supplemented with either 0.1% glucose or 0.1% glucose and 1 mM MgSO4. Cultures in 160-mm test tubes were shaken (180 strokes per min at a 45° angle) for 6 h at 37°C. For phase-contrast microscopy at a magnification of ×2,000, a sample was mixed with 0.1 volume of 20% formaldehyde and applied to a slide.

RESULTS

Nucleotide sequence of pgcA in wild-type and mutant strains.

The pgcA gene (previously the yhxB gene [16]) of B. subtilis was reported to encode a 565-amino-acid protein exhibiting similarity to several characterized and many putative α-PGMs (data not shown). When the similarity search was limited to characterized α-PGMs, the best score (46% identity) was obtained with the α-PGM of Streptococcus thermophilus (18).

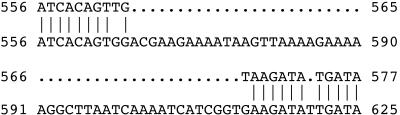

To determine whether gtaC and gtaE mutations map to pgcA, relevant DNA segments from α-PGM-deficient mutants L6179 (gtaC189), L6188 (gtaC198), L6118 (gtaE151), and L6125 (gtaE158), as well as from strain 168, were amplified by PCR and sequenced. A comparison of the sequences of the mutants to that of strain 168 revealed specific single-nucleotide differences (Table 2). The two gtaC mutations and the two gtaE mutations are located in the 5′ and 3′ moieties of pgcA, respectively. All of these mutations result in radical amino acid replacements. The previously published strain 168 genomic sequence (16) appeared to contain two deletions (47 nucleotides and 1 nucleotide) (Fig. 1). These deletions either had occurred spontaneously in the B. subtilis 168 lineage used in the sequencing project or were due to the instability of the corresponding plasmid clone. Thus, the corrected nucleotide sequence with a 581-amino-acid coding capacity (accession number AJ784890) was considered the wild-type sequence.

TABLE 2.

Base changes and resulting amino acid replacements corresponding to mutations in pgcA

| Strain (mutation) | Base change (amino acid)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| From | To | |

| L6179 (gtaC189) | GGC (162Gly) | GAC (Asp) |

| L6188 (gtaC198) | ACT (240Thr) | ATT (Ile) |

| L6118 (gtaE151) | GGT (407Gly) | GAT (Asp) |

| L6125 (gtaE158) | GAC (418Asp) | AAC (Asn) |

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the pgcA sequence from the B. subtilis 168 genome sequencing project (top line) with the pgcA sequence obtained in this study (bottom line). The numbers are the positions relative to the pgcA start codon.

Characterization of gtaC and gtaE mutants.

To confirm that the mutations that were identified were indeed responsible for the characteristic phage resistance spectrum and α-PGM deficiency, mutations gtaC189 and gtaE151 were backcrossed by pseudolinkage into strain 168. B. subtilis 168 trpC2 competent cells were cotransformed with pTRP-H3 and either p647 (gtaC189) or p648 (gtaE151). In each cross a fraction of selected Trp+ transformants were resistant to both φ29 and ρ11 (data not shown) and formed characteristic round, shiny colonies (28). Strain L16135 also acquired resistance to the defective phage PBSZ (data not shown), an intrinsic characteristic of gtaE strains (28). Representative phage-resistant transformants, designated L16134 (gtaC189) and L16135 (gtaE151), were retained and used for further investigation. Transfer of the relevant mutation was confirmed by sequencing pgcA in L16134 and L16135.

As expected, assays of the soluble cell extract fraction of L16134 (gtaC189) and L16135 (gtaE151) confirmed that α-PGM activity was severely impaired in both mutants. In our experimental conditions, the α-PGM activity in strain L16134 (gtaC189) was very low but detectable, whereas the α-PGM activity in strain L16135 (gtaE151) was undetectable (Table 3). Therefore, our results showing that single nucleotide substitutions in pgcA led to the characteristic phenotype of gtaC and gtaE mutants demonstrated that pgcA is the structural gene of α-PGM.

TABLE 3.

α-PGM activity in crude extracts

| Strain(mutation) | α-PGM activity (nmol · mg of cell protein−1 · min−1)a |

|---|---|

| 168 | 15.9 ± 0.9b |

| L16134 (gtaC) | 0.5 ± 0.1c |

| L16135 (gtaE) | 0 |

Enzymatic activity was measured in triplicate samples and is expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

The reaction velocity was linear for at least 1 h.

α-PGM activity decreased with time. Calculation of the activity was based on the difference in the A340 between samples taken at 30 min and zero time.

Role of pgcA in biofilm formation.

In contrast to the wild type, gtaC- and gtaE-deficient mutants are characterized by a shiny colony morphology, a phenotype shared with mutants deficient in GtaB. The report that in Vibrio cholerae a difference in colony morphology correlates with the ability to colonize abiotic surfaces (22) prompted us to investigate a possible role of the B. subtilis pgcA gene in biofilm formation.

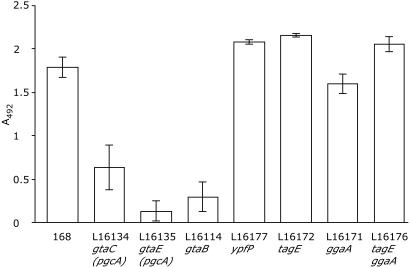

Biofilm formation was assayed by determining the ability of B. subtilis to attach to wells of microtiter polyvinyl chloride plates during 70 h of incubation in LB medium supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 and 0.1% glucose (8, 32), and it was quantified by staining with safranin. As shown in Fig. 2, biofilm formation by strains bearing gtaC and gtaE mutations was greatly diminished compared to biofilm formation by the wild type. The relatively low level of safranin staining, measured at A492, was apparently not due to poor growth of the mutants since the OD600 measured after 46 and 70 h of incubation, as well as the viable counts after 70 h of incubation, were comparable to the values for the wild type (data not shown). Moreover, a decrease in the safranin staining of biofilms produced by α-PGM-deficient strains did not seem to be due to an inability of the dye to bind to the mutant cells. Indeed, the OD600 of suspended untreated biofilms of gtaC and gtaE mutants were about three- and sixfold lower, respectively, than the OD600 of the wild type (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Quantitation of biofilm formation. The biofilm formed on polyvinyl chloride after 70 h of incubation is expressed as the A492 of solubilized safranin from a microtiter plate assay. The data are averages of three to five independent experiments, each performed in at least 20 wells. The error bars indicate standard errors of the means. The differences between the mutants and the wild-type strain appear to be significant (P < 0.01) except for the ggaA-deficient strain (P > 0.05).

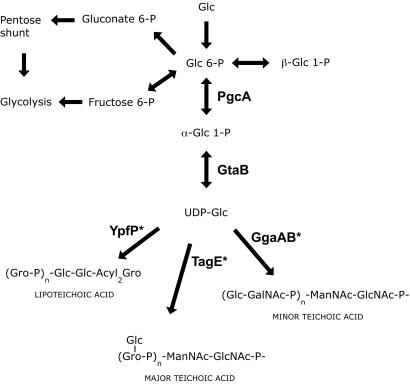

Since the deficiency in α-PGM affects the synthesis of all known cell envelope anionic polymers (Fig. 3), mutants with mutations in the gtaB, ypfP, tagE, and ggaA genes, whose products intervene in later stages of the synthesis of envelope polymers (Fig. 3), were constructed and assayed for biofilm formation. To assess the possibility of a synergistic effect on biofilm formation of both WTAs [i.e., glucosylated poly(Gro-P) and poly(glucosyl N-acetylgalactosamine phosphate)], a tagE ggaA double mutant was constructed and assayed.

FIG. 3.

Involvement of glucose derivatives in the synthesis of WTAs and LTA. Enzymes that catalyze transfer of glucose from UDP-Glc in the synthesis of the corresponding polymer are indicated by an asterisk. ManNAc, N-acetylmannosamine; GalNAc, N-acetylgalactosamine.

As expected, the mutant with a gtaB knockout was also deficient in biofilm formation. Surprisingly, none of other mutants investigated was significantly impaired in biofilm formation.

Cell morphology of mutants affected in the synthesis of Glc 6-P metabolites.

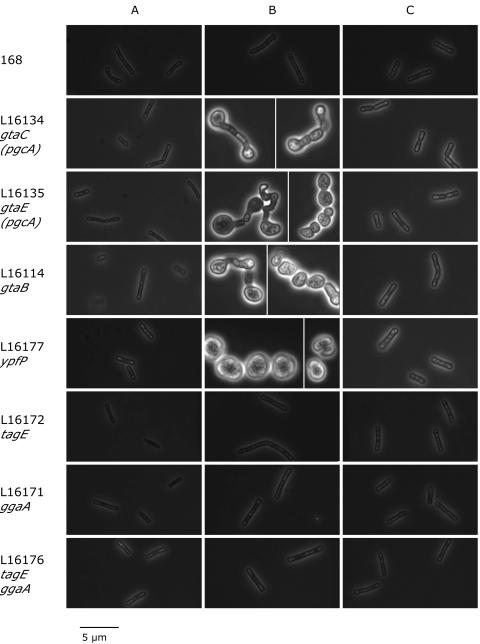

Routine microscopic examination of B. subtilis cultures revealed t hat strains bearing gtaC and gtaE mutations had apparently normal cell morphology on LB agar plates (Fig. 4A). However, in liquid LB medium they exhibited a deformed cell shape (Fig. 4B) that was reversed by addition of 1 mM MgSO4 (Fig. 4C) or 1 mM MgCl2 but not by addition of 1 mM CaCl2 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cell morphology of the wild-type and mutant B. subtilis strains. Cells grown overnight on LB agar plates at 37°C were resuspended in liquid media. Samples were taken immediately from LB broth containing 0.1% glucose (A), after 6 h of incubation in LB broth supplemented with 0.1% glucose (B), and after 6 h of incubation in LB broth supplemented with 0.1% glucose and 1 mM MgSO4 (C).

gtaB and ypfP mutants exhibited similar dependence on Mg2+ for cell morphology in LB broth. However, other mutants deficient in portions of the biosynthetic pathway downstream of the UDP-Glc formation step (i.e., tagE and ggaA mutants), as well as the tagE ggaA double mutant, were characterized by apparently normal morphology irrespective of the presence of additional Mg2+ during growth in liquid LB medium.

LTA content of mutants affected in the synthesis of Glc 6-P metabolites.

According to the accepted knowledge concerning B. subtilis metabolism (Fig. 3), pgcA-, gtaB-, and ypfP-deficient strains should not be able to synthesize diglucosyldiacylglycerol, the LTA lipid anchor. However, it appeared that in these mutants incorporation of the poly(Gro-P) moiety of LTA was comparable to that in the wild type (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In B. subtilis, Glc 6-P is formed by phosphorylation of glucose that enters the cell, as well as by the β-PGM (PgcM; EC 5.4.2.6)-governed conversion of β-Glc 1-P obtained by maltose degradation (21). On the one hand, Glc 6-P undergoes glycolysis, yielding energy and reducing power, and on the other hand, it is isomerized by pgcA-encoded α-PGM into α-Glc 1-P, the precursor of UDP-Glc. UDP-Glc serves as a glucosyl donor for the synthesis of all phosphate-containing anionic envelope polymers in B. subtilis strain 168 (Fig. 3).

Sequencing of pgcA in four α-PGM-deficient strains revealed that relevant mutations, originally designated gtaC and gtaE, map to this open reading frame. In a previous study based on classical genetic methods, the possibility that the gtaCE locus contains more than one gene was raised (28). This possibility may now be understood based on the fact that the length of pgcA (1.7 kb) corresponds to the length of nearly two average-size B. subtilis genes, as well as the distinct locations of mutations previously designated gtaC and gtaE, the latter located in the 3′-terminal part of the gene and the former located in the 5′-terminal part of the gene.

Analysis of strains carrying gtaC and gtaE mutations confirmed that pgcA is the structural gene of α-PGM in B. subtilis 168. Mutants deficient in α-PGM activity are impaired in biofilm formation and, in LB broth, display altered cell morphology. These phenotypes are more pronounced in gtaE mutants than in gtaC mutants.

Likewise, inactivation of gtaB also affects biofilm formation. Since PgcA and GtaB catalyze successive steps in UDP-Glc synthesis (Fig. 3), the biofilm formation deficiency is likely to be due to a reduced intracellular pool of UDP-Glc. UDP-Glc might act as a metabolic signal regulating biofilm formation, or, alternatively, it may take part in another, unknown, biosynthetic pathway essential for biofilm formation. This could be, for instance, the synthesis of an exopolysaccharide, as recently proposed by Branda at al. (3).

The biofilm-forming capacity of B. subtilis has been shown to depend on Spo0A, the key master regulator that governs entry into sporulation, and the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor SigH (4). Biofilm formation is inhibited by catabolite repression (8, 32). Many of the genes differentially expressed during biofilm formation are involved in motility and chemotaxis, phage-related functions, membrane bioenergetics, and sugar catabolism (32). It is likely that expression of other genes required for biofilm formation, including pgcA and gtaB, is not significantly altered upon transition from the planktonic mode to the sessile mode.

Interestingly, our strain carrying the tagE12 mutation, which was not capable of poly(Gro-P) glucosylation, apparently produced more biofilm than strain 168, while Hamon et al. (9) reported a twofold decrease in the level of biofilm formation for a tagE knockout mutant obtained by plasmid integration. The biofilm defect, as well as the reduced growth rate of the latter mutant, could have been due to deregulated expression of the downstream gene tagF that encodes the enzyme catalyzing the extension of the poly(Gro-P) backbone of the major WTA (27).

Mutations in the pgcA, gtaB, and ypfP genes, encoding enzymes which catalyze three consecutive steps in the synthesis of diglucosyldiacylglycerol (Fig. 3), were associated with aberrant cell morphology (i.e., development of grossly deformed spheres during growth in liquid LB medium). The deformations were more striking than those reported in previous studies (29; unpublished data). We can attribute these differences to chemical variations in the LB medium formulations used (for instance, the concentrations of bivalent cations), since the observed mutant morphology was shown to be suppressed by excess magnesium ions.

The level of the poly(Gro-P) moiety of LTA was not affected in the pgcA-, gtaB-, and ypfP-deficient mutants, suggesting that in absence of glucosylated diacylglycerol, LTA is anchored to the membrane by unsubstituted diacylglycerol (5, 15). Glucosylated forms of diacylglycerol also occur as free membrane glycolipids in different bacteria, including B. subtilis (12, 15). It has been proposed that they play a role in membrane stability. Therefore, it is possible that Mg2+ in association with other membrane constituents can functionally replace missing membrane glycolipids. Replacement of the usual LTA anchor and/or a deficiency of membrane glycolipids may affect the cell morphology in a more indirect way (for instance, by impeding access of magnesium ions to envelope synthetic enzymes). Raising the Mg2+ concentration of the medium would be expected to palliate this defect. Similarly, Wagner and Stewart (33) reported that magnesium reversed the altered morphology due to a mutation in the major WTA polymerizing enzyme gene, tagF (rodC). Again, in this mutant, the flow of magnesium ions from the medium to the membrane is expected to be impaired, assuming that the cascade transfer of this cation from the medium to the membrane involves WTA and LTA (11).

In conclusion, mutations in pgcA, which encodes the enzyme that provides a link between glycolysis and envelope biosynthetic processes, have pleiotropic effects, some of which are correlated with an inability to produce UDP-Glc. The biofilm formation deficiency may be due to an absence of UDP-Glc, which may be a precursor of a putative compound required for biofilm formation, whereas the altered cell morphology may be correlated with a deficiency of membrane glycolipids.

ADDENDUM

During the review process for this paper Branda et al. (3) also reported that yhxB (pgcA) is involved in B. subtilis community development.

TABLE 4.

Incorporation of [2-3H]glycerol label into LTA of parent and mutant strains

| Strain (mutation) | % of total labela |

|---|---|

| 168 | 7.84 ± 0.43 |

| L16114 (gtaB) | 8.08 ± 0.24 |

| L16134 (gtaC) | 8.27 ± 0.52 |

| L16135 (gtaE) | 8.09 ± 0.25 |

| L16177 (ypfP) | 9.29 ± 0.49 |

The total glycerol label was the label incorporated into LTA, phospholipids, and WTA. The values are means ± standard deviations of three samples labeled for five generations at 37°C.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aude Bachelard and Florence Adamer for their help with some experiments.

This work was supported by grant 3100A0-A102205 from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of Catherine Mauël (1943-2004).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostopoulos, C., P. J. Piggot, and J. A. Hoch. 1993. The genetic map of Bacillus subtilis, p. 425-461. In A. L. Sonenshein, J. A. Hoch, and R. Losick (ed.), Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 2.Band, L., H. Shimotsu, and D. J. Henner. 1984. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus subtilis trpE and trpD genes. Gene 27:55-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branda, S. S., J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, E. Dervyn, S. D. Ehrlich, R. Losick, and R. Kolter. 2004. Genes involved in formation of structured multicellular communities by Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 186:3970-3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branda, S. S., J. E. Gonzalez-Pastor, S. Ben-Yehuda, R. Losick, and R. Kolter. 2001. Fruiting body formation by Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:11621-11626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Button, D., and N. L. Hemmings. 1976. Teichoic acids and lipids associated with the membrane of a Bacillus licheniformis mutant and the membrane lipids of the parental strain. J. Bacteriol. 128:149-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estrela, A. I., H. M. Pooley, H. de Lencastre, and D. Karamata. 1991. Genetic and biochemical characterization of Bacillus subtilis 168 mutants specifically blocked in the synthesis of the teichoic acid poly(3-O-beta-d-glucopyranosyl-N-acetylgalactosamine 1-phosphate): gneA, a new locus, is associated with UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 4-epimerase activity. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:943-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Genevaux, P., S. Muller, and P. Bauda. 1996. A rapid screening procedure to identify mini-Tn10 insertion mutants of Escherichia coli K-12 with altered adhesion properties. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 142:27-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamon, M. A., and B. A. Lazazzera. 2001. The sporulation transcription factor Spo0A is required for biofilm development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 42:1199-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamon, M. A., N. R. Stanley, R. A. Britton, A. D. Grossman, and B. A. Lazazzera. 2004. Identification of AbrB-regulated genes involved in biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 52:847-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honeyman, A. L., and G. C. Stewart. 1989. The nucleotide sequence of the rodC operon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 3:1257-1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes, A. H., I. C. Hancock, and J. Baddiley. 1973. The function of teichoic acids in cation control in bacterial membranes. Biochem. J. 132:83-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jorasch, P., F. P. Wolter, U. Zahringer, and E. Heinz. 1998. A UDP glucosyltransferase from Bacillus subtilis successively transfers up to four glucose residues to 1,2-diacylglycerol: expression of ypfP in Escherichia coli and structural analysis of its reaction products. Mol. Microbiol. 29:419-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karamata, D., and J. D. Gross. 1970. Isolation and genetic analysis of temperature-sensitive mutants of B. subtilis defective in DNA synthesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 108:277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karamata, D., H. M. Pooley, and M. Monod. 1987. Expression of heterologous genes for wall teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis 168. Mol. Gen. Genet. 207:73-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiriukhin, M. Y., D. V. Debabov, D. L. Shinabarger, and F. C. Neuhaus. 2001. Biosynthesis of the glycolipid anchor in lipoteichoic acid of Staphylococcus aureus RN4220: role of YpfP, the diglucosyldiacylglycerol synthase. J. Bacteriol. 183:3506-3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, M. G. Bertero, P. Bessieres, A. Bolotin, S. Borchert, R. Borriss, L. Boursier, A. Brans, M. Braun, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, S. Brouillet, C. V. Bruschi, B. Caldwell, V. Capuano, N. M. Carter, S. K. Choi, J. J. Codani, I. F. Connerton, A. Danchin, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazarevic, V., H. M. Pooley, C. Mauël, and D. Karamata. 2002. Teichoic and teichuronic acids from gram-positive bacteria, p. 465-492. In E. J. Vandamme, S. de Baets, and A. Steinbüchel (ed.), Biopolymers, vol. 5. Polysaccharides I: polysaccharides from prokaryotes, vol. 5. Wiley-VCH Verlag, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levander, F., and P. Radstrom. 2001. Requirement for phosphoglucomutase in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis in glucose- and lactose-utilizing Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2734-2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mauël, C., M. Young, and D. Karamata. 1991. Genes concerned with synthesis of poly(glycerol phosphate), the essential teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis strain 168, are organized in two divergent transcription units. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137:929-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauël, C., M. Young, P. Margot, and D. Karamata. 1989. The essential nature of teichoic acids in Bacillus subtilis as revealed by insertional mutagenesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 215:388-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mesak, L. R., and M. K. Dahl. 2000. Purification and enzymatic characterization of PgcM: a β-phosphoglucomutase and glucose-1-phosphate phosphodismutase of Bacillus subtilis. Arch. Microbiol. 174:256-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nesper, J., C. M. Lauriano, K. E. Klose, D. Kapfhammer, A. Kraiss, and J. Reidl. 2001. Characterization of Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor galU and galE mutants: influence on lipopolysaccharide structure, colonization, and biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 69:435-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nester, E. W., J. H. Lorence, and D. S. Nasser. 1967. An enzyme aggregate involved in the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids in Bacillus subtilis. Its possible function in feedback regulation. Biochemistry 6:1553-1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuhaus, F. C., and J. Baddiley. 2003. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of d-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:686-723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oultram, J. D., H. Peck, J. K. Brehm, D. E. Thompson, T. J. Swinfield, and N. P. Minton. 1988. Introduction of genes for leucine biosynthesis from Clostridium pasteurianum into C. acetobutylicum by cointegrate conjugal transfer. Mol. Gen. Genet. 214:177-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pooley, H. M., and D. Karamata. 2000. Incorporation of [2-3H]glycerol into cell surface components of Bacillus subtilis 168 and thermosensitive mutants affected in wall teichoic acid synthesis: effect of tunicamycin. Microbiology 146:797-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pooley, H. M., F.-X. Abellan, and D. Karamata. 1992. CDP-glycerol:poly(glycerophosphate) glycerophosphotransferase, which is involved in the synthesis of the major wall teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis 168, is encoded by tagF (rodC). J. Bacteriol. 174:646-649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pooley, H. M., D. Paschoud, and D. Karamata. 1987. The gtaB marker in Bacillus subtilis 168 is associated with a deficiency in UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:3481-3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price, K. D., S. Roels, and R. Losick. 1997. A Bacillus subtilis gene encoding a protein similar to nucleotide sugar transferases influences cell shape and viability. J. Bacteriol. 179:4959-4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Soldo, B., V. Lazarevic, P. Margot, and D. Karamata. 1993. Sequencing and analysis of the divergon comprising gtaB, the structural gene of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase of Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:3185-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanley, N. R., R. A. Britton, A. D. Grossman, and B. A. Lazazzera. 2003. Identification of catabolite repression as a physiological regulator of biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis by use of DNA microarrays. J. Bacteriol. 185:1951-1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner, P. M., and G. C. Stewart. 1991. Role and expression of the Bacillus subtilis rodC operon. J. Bacteriol. 173:4341-4346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasbin, R. E., V. C. Maino, and F. E. Young. 1976. Bacteriophage resistance in Bacillus subtilis 168, W23, and interstrain transformants. J. Bacteriol. 125:1120-1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young, F. E. 1967. Requirement of glucosylated teichoic acid for adsorption of phage in Bacillus subtilis 168. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 58:2377-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]