Abstract

The influence of environmental parameters on the diversity of methanogenic communities in 15 full-scale biogas plants operating under different conditions with either manure or sludge as feedstock was studied. Fluorescence in situ hybridization was used to identify dominant methanogenic members of the Archaea in the reactor samples; enriched and pure cultures were used to support the in situ identification. Dominance could be identified by a positive response by more than 90% of the total members of the Archaea to a specific group- or order-level probe. There was a clear dichotomy between the manure digesters and the sludge digesters. The manure digesters contained high levels of ammonia and of volatile fatty acids (VFA) and were dominated by members of the Methanosarcinaceae, while the sludge digesters contained low levels of ammonia and of VFA and were dominated by members of the Methanosaetaceae. The methanogenic diversity was greater in reactors operating under mesophilic temperatures. The impact of the original inoculum used for the reactor start-up was also investigated by assessment of the present population in the reactor. The inoculum population appeared to have no influence on the eventual population.

Anaerobic digestion is a simple and effective biological process for the treatment of different organic wastes and the production of energy in the form of biogas (1). A number of full-scale anaerobic digesters for biogas production have been developed and installed in Denmark during the last 20 years (27). They have been designed mainly for the codigestion of manure with a smaller fraction of other waste as a supplemental substrate. Specific environmental and operating factors influence anaerobic conversion processes in these codigestion plants, and similar factors also have an influence on wastewater primary and activated sludge (WW sludge) digesters. Some of the more important factors are temperature (4), ammonia level (7), and loading rate, which affects overall process stability, generally as measured by the concentrations of volatile fatty acids (VFA) in the digester (2).

Anaerobic digestion is a multistep microbial process mediated by functionally different microbial groups—saccharide and amino acid fermenters, VFA oxidizers, and methanogens (17, 21). The two functional groups of methanogens (hydrogenotrophic and aceticlastic) have been well described in terms of physiology and phylogeny (11). Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis and aceticlastic methanogenesis are also the key processes within anaerobic digestion, as when these processes are inhibited, digestion is effectively blocked at acidogenesis. Optimization of methanogenesis is difficult, because of both low growth rates and the susceptibility of the organisms to toxins (6).

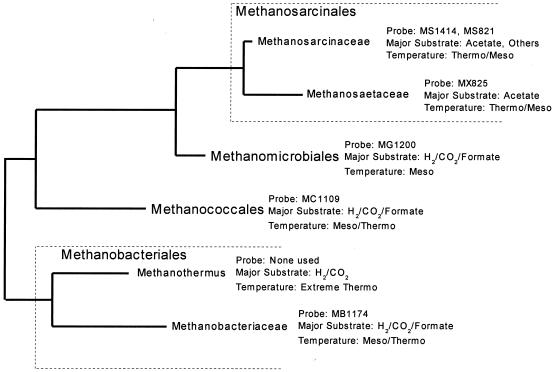

Organisms described as mediating hydrogenotrophic and aceticlastic methanogenesis are found within five phylogenetic orders (12). One of the hydrogenotrophic orders, Methanopyrales, has only hyperthermophilic member species and will not be considered further. The main orders and their characteristics are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Main characteristics of methanogenic orders

| Order | Cell morphology | Physiology |

|---|---|---|

| Methanobacteriales | Rods or filaments | Hydrogenotrophic; mesophilic or thermophilic |

| Methanococcales | Irregular cocci | Hydrogenotrophic; mesophilic or thermophilic |

| Methanomicrobiales | Small rods, irregular cocci, flat oval-shaped cells | Hydrogenotrophic; mesophilic |

| Methanosarcinales | Rods or filaments (Methanosaetaceae), irregular cocci or Sarcina-like cells (Methanosarcinaceae) | Strict aceticlastic (Methanosaetaceae), aceticlastic or hydrogenotrophic (Methanosarcinaceae); mesophilic or thermophilic |

Microbial investigation of methanogens can assist in the classification and optimization of anaerobic digestion systems (12). Numerous classical microbiological and molecular methods are available for the identification of methanogens (8), but most do not allow in situ analysis of a system. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has been successfully used as a simple and rapid technique suitable for the assessment of a wide range of samples from environmental and engineered systems (10). It allows the simultaneous visualization, identification, and localization of individual microbial cells and, when used with order-level probes, can separate microbial groups with different functions.

The compositions of methanogenic communities present in anaerobic reactors have been studied mostly for laboratory-scale digesters, including up-flow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor granules (23) and mixture reactors treating municipal solid waste (MSW) or wastewater sludge (18, 20). Methanogenic diversity in manure-treating biogas plants has been studied mainly to describe syntrophy between VFA-oxidizing Bacteria and hydrogenotrophic methanogens (13). Current knowledge is limited in that a broad range of systems have not been surveyed. In addition, the influence of environmental and operating conditions, such as temperature, organic acid concentrations, ammonia concentrations, and loading rate, have not been assessed in conjunction with the methanogenic community. Assessing these limitations may allow for better optimization of the process by identifying key inhibitory elements or a microbial basis for poor operation.

The objective of this work was to address these limitations by assessing the methanogenic communities in a large range of full-scale manure-fed and wastewater sludge-fed anaerobic digesters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling from full-scale plants.

A total of 15 Danish full-scale biogas plants operating at different temperatures, hydraulic retention times, biogas production rates, and VFA and ammonia levels were sampled (Table 2). All digesters were of similar design, with recycle-gas mixing. The capacity of the plants varied from 50 to 500 tons of feedstock per day (27). The feedstock for nine of the digesters studied (Vegger, Sinding, Fangel, Lemvig, Hashoj, Studsgard, Snertinge, Nysted, and Revninge) consisted of 70 to 90% animal manure and 10 to 30% organic waste from abattoirs or food industries. Five plants (Fakse, Lundtofte, Hillerod, Helsignor, and Sydkyst) were fed with WW sludge. One plant, Grindsted, was fed with WW sludge (main fraction) and with MSW. To assess a number of other factors (including enrichment or isolation bias and subdominant microbial groups), samples from four reactors (Grinsted, Fangel, Vegger and Lemvig) were enriched and isolated for aceticlastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogens. Enrichments were also attempted for samples in which the dominant methanogen was not identified (Sinding and Hashoj reactors).

TABLE 2.

Systems analyzed and operating conditions

| Plant name | Main component in digested feedstock | Reactor vol (m3) | HRTc (days) | Biogas production (m3 m−3 day−1)a | Operating temp (°C): | Level (mean ± SD) of:b

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VFA (g of HAc eq liter−1) | Ammonia (g of N liter−1) | ||||||

| Vegger | Manure | 1,400 | 17 | 6.3 | 55 | 0.7 ± 0.02 | 3.2 ± 0.11 |

| Sinding | Manure | 2,250 | 18 | 2.9 | 51 | 0.5 ± 0.02 | 2.7 ± 0.13 |

| Fangel | Manure | 4,400 | 20 | 1.6 | 37 | 1.6 ± 0.06 | 4.1 ± 0.18 |

| Lemvig | Manure | 7,000 | 15 | 1.9 | 52.5 | 0.8 ± 0.03 | 3.0 ± 0.15 |

| Hashoj | Manure | 2,900 | 20 | 2.7 | 37 | 1.5 ± 0.07 | 6.1 ± 0.22 |

| Studsgard | Manure | 6,600 | 25 | 2.6 | 52 | 0.4 ± 0.02 | 2.1 ± 0.11 |

| Snertinge | Manure | 2,800 | 20 | 1.5 | 51.5 | 3.0 ± 0.12 | 2.8 ± 0.14 |

| Nysted | Manure | 5,000 | 25 | 1.4 | 38 | 2.0 ± 0.08 | 3.3 ± 0.16 |

| Revninge | Manure | 3,000 | 25 | 1.0 | 37 | 0.3 ± 0.01 | 3.6 ± 0.10 |

| Grinsted | WW sludge and MSW | 2,915 | 23 | 0.9 | 38 | 0.1 ± 0.004 | 1.2 ± 0.01 |

| Fakse | WW sludge | 3,000 | 20 | 1.8 | 37 | 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.01 |

| Lundofte | WW sludge | 5,000 | 30 | 3.3 | 37 | 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.01 |

| Hillerod | WW sludge | 1,893 | 30 | 0.7 | 55 | 0.01 ± 0.0001 | 0.1 ± 0.001 |

| Helsingor | WW sludge | 1,400 | 30 | 0.5 | 37 | 0.07 ± 0.0003 | 0.2 |

| Sydkyst | WW sludge | 945 | 30 | 0.6 | 37 | 0.01 ± 0.0002 | 0.03 |

No standard deviations are shown for biogas production because the values were averages obtained from system operators.

Standard deviations were based on triplicate analyses. HAc eq, acetate equivalents.

HRT, hydraulic retention time.

Samples were collected in thermally insulated 10-liter polyvinyl chloride containers. The containers had a one-way valve on the lid to release overpressure due to methane production. The containers were gassed with N2 to ensure an anaerobic environment for the samples during transportation. All reactors had sample points in the effluent lines close to the reactors. The sampling valve was opened for 5 min before sample acquisition to flush the sampling valve and tube. After sampling, the containers were immediately closed and transported to the laboratory within 1 day. Three independent samples from each reactor were analyzed (1-month sample frequency), and each sample was analyzed for ammonia, organic acids, and methanogenic community. Duplicate hybridizations were done for each sample, with six or seven analyses (with different probes) in each hybridization. Several reactors (both manure and sludge digesters) were sampled approximately 1 year apart to check for long-term changes.

FISH.

The FISH method of Hugenholtz et al. (14) was used with reactor samples, enrichment cultures, and pure cultures. The probes used and their target orders or families are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1. The probes were used both at optimal stringency (data were from the references listed in Table 3) and at 20% formamide. ARC915 was used to identify all members of the Archaea, and a combination of EUB338 and EUB338+ was used for all members of the Bacteria. We also used 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole for total cell identification (0.33 μg ml−1 in MilliQ water for 5 min). After hybridization, the slides were examined by confocal laser scanning microscopy with a Zeiss LSM 510 microscope, an upright Axioplan 2 microscope, and an ApoChromat microscope with a 63× objective and a 1.4 aperture. An upright Axioplan epifluorescence microscope was also used. Excitation channels were 488 nm (green emission filter) and 545 nm (red emission filter) for fluorescein isothiocyanate and Cy3 fluorochromes, respectively. The observations reported here were based on approximately 20 microscope fields examined with the 63 × 1.4 objective, representing approximately 2,000 to 10,000 individual cells.

TABLE 3.

Oligonucleotide probes used

| Probe | Phylogenetic group | Functional groupa | Probe sequence (5′-3′)b | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUB338 | Bacteria (most) | Non-meth. | GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT | 26 |

| EUB338+ | Bacteria (remaining) | GCWGCCACCCGTAGGTGT | 9 | |

| ARC915 | Archaea | Mainly meth. | GTGCTCCCCCGCCAATTCCT | 26 |

| MX825 | Methanosaetaceae | Aceticlastic meth. | TCGCACCGTGGCCGACACCTAGC | 19 |

| MS1414 | Methanosarcinaceaec | Aceticlastic meth. (also hydrogen) | CTCACCCATACCTCACTCGGG | 23 |

| MG1200 | Methanomicrobiales | Hydrogenotrophic meth. | CGGATAATTCGGGGCATGCTG | 23 |

| MB1174 | Methanobacteriales | Hydrogenotrophic meth. | TACCGTCGTCCACTCCTTCCTC | 23 |

| MC1109 | Methanococcales | Hydrogenotrophic meth. | GCAACATAGGGCACGGGTCT | 19 |

meth., methanogenic.

W, A+T mixed base.

Probe MS821 (CGCCATGCCTGACACCTAGCGAGC) (19) was also used.

FIG. 1.

Order-level classification of methanogens, excluding Methanopyrales, with order-level and family-level probes, main substrates, and operating temperatures.

Medium.

Basal anaerobic (BA) medium was used for enrichment, isolation, and routine cultivation as described previously (5) under an N2-CO2 (80:20) headspace. l-Cysteine hydrochloride was omitted, and the concentration of Na2S · 9H2O was increased to 0.25 g/liter. The medium was autoclaved in 40-ml portions in 100-ml serum bottles. Prior to inoculation, the medium was reduced with a sterile anaerobic solution of Na2S · 9H2O and supplemented with sterilely filtered anaerobic vitamin solution (10 ml liter−1) as described previously (28).

Enrichment, isolation, and cultivation.

Two kinds of enrichment cultures were developed for each sample: (i) enrichment for the isolation of aceticlastic methanogens in BA medium with sodium acetate at a final concentration of 20 mM as a substrate and (ii) enrichment for the isolation of hydrogenotrophic methanogens in BA medium pressurized with H2-CO2 (80:20) at a 101-kPa overpressure as a substrate.

The enrichment cultures were made as batch cultivations in serum vials with 10% successive inoculations. The serum vials were incubated for 1 to 2 months under mesophilic (37°C) or thermophilic (55°C) conditions in accordance with the process temperatures of the individual biogas plants from which the samples originated. During this period, a sterile H2-CO2 (80:20) gas mixture was added to the H2-CO2 enrichment cultures every 3 to 4 days. Pure methanogenic isolate culturing from these enrichments was attempted by using a roll-tube technique (15).

Analytical methods.

Methane and VFA were analyzed by gas chromatography as described previously (25). Ammonia was analyzed as described previously (3). Reagent-grade chemicals were used for all analyses. All analyses were done in triplicate. Averages are presented along with corresponding standard deviations calculated from the triplicate analyses.

RESULTS

Methanogenic diversity in biogas reactor samples.

The samples generally contained large amounts of autofluorescent material, with various responses. Therefore, it was impossible to use machine counting or area identification methods to automatically evaluate microbial abundance quantitatively. However, it was very easy for a trained observer to discern a dominant microbial group, which was obvious in all samples examined in this study. Dominance is defined as a positive response to the group-level probe by over 90% of the individual cells within members of the Archaea, as identified by the ARC915 probe. Nondominant microbial groups could by identified by their presence; when nondominant groups were observed, they represented between 1 and 10% of all members of the Archaea. No observable differences in methanogenic communities were found between duplicate hybridizations for the same sample or for monthly replicates or yearly replicates from the same systems, and measured organic acid and ammonia concentrations were also consistent (monthly replicates).

An overview of the results obtained is shown in Table 4. Most manure digesters were dominated by members of the Methanosarcinaceae, while sewage sludge digesters were uniformly dominated by members of the Methanosaetaceae. The most frequently observed hydrogen utilizers were members of the Methanobacteriales, occurring in both manure and sewage sludge digesters. In addition, members of the Methanobacteriales were difficult to observe, because of their small size, and may have been present but not identified in other plants. Members of the Methanococcales and Methanomicrobiales were less widespread. Methanogens from the Hashoj and Sinding manure-digesting plants were not identified with the oligonucleotide probes used. Organisms assumed to be aceticlastic (Methanosarcinaceae and Methanosaetaceae) were more abundant than organisms assumed to be hydrogenotrophic (Methanobacteriales, Methanomicrobiales, and Methanococcales).

TABLE 4.

Methanogenic diversity in plant samplesa

| Plant name | Methanogens in the following samples

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw

|

Enriched with:

|

|||

| Dominant | Nondominant | Acetate | H2-CO2 | |

| Vegger | MS | NO | MS | MB |

| Sinding | UnIDd short rods and cocci binding to ARC915 | NO | MS | MG, MC |

| Fangel | MS, MB | MG, MC | MS | UnIDd long rods binding to ARC915 |

| Lemvig | MB | NO | MS, MX | MB |

| Hashoj | UnIDd long rods binding to ARC915 | NO | UnIDd short rods binding to ARC915 | UnIDd long rods binding to ARC915 |

| Studsgard | MS | NO | ||

| Snertinge | MS | NO | ||

| Nysted | MS | NO | ||

| Revninge | MS, MB | NO | ||

| Grinsted | MX | NO | MX | MB |

| Fakse | MX | MS | ||

| Lundtofte | MX | NO | ||

| Hillerod | MX | NO | ||

| Helsingor | MX | NO | ||

| Sydkyst | MX | NO | ||

MS, Methanosarcinaceae; NO, not observed; MB, Methanobacteriales; UnIDd, unidentified; MG, Methanomicrobiales; MC, Methanococcales; MX, Methanosaetaceae. The term “dominant methanogens” was used in the sense of more than 90% of the total number of methanogenic cells (Archaea responding to ARC915). The term “nondominant methanogens” was used in the sense of 1 to 10% of the total number of methanogenic cells. Cells in 20 fields were counted.

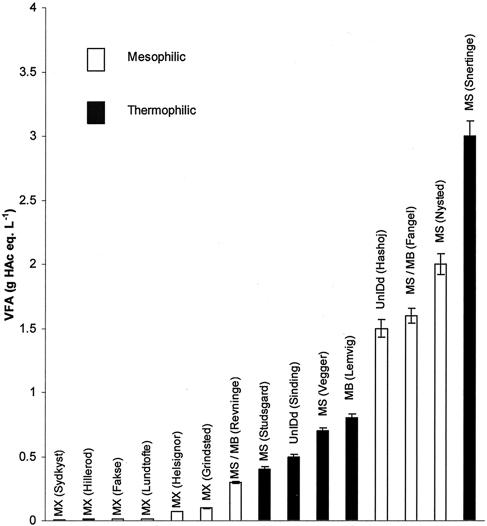

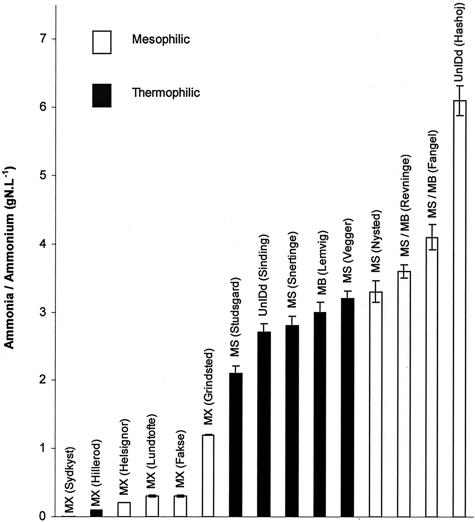

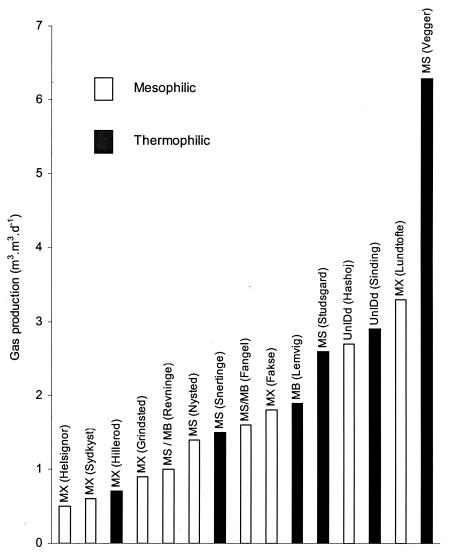

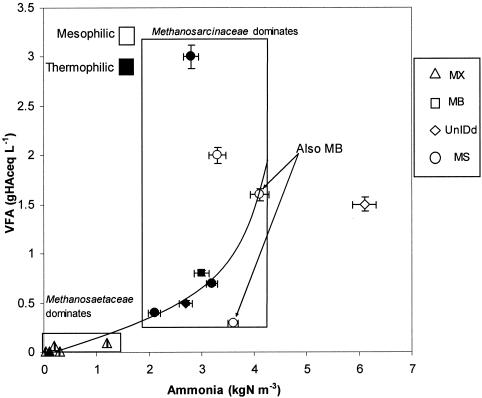

Organic acid concentrations were low in all sludge digesters (dominated by Methanosaetaceae) (Fig. 2). Organic acid concentrations were significantly higher in manure digesters, mostly dominated by methanogens of the Methanosarcinaceae. The influence of ammonia or ammonium was also effectively bimodal, because the manure digesters had high ammonia concentrations, while the sludge digesters had low ammonia concentrations (Fig. 3). Gas production rates (Fig. 4) appeared to have no apparent influence, but this finding was largely a function of loading rates, which therefore also appeared to have no influence on the dominant methanogens observed.

FIG. 2.

Dominant methanogens in different digesters observed as a function of organic acid concentrations. Labels indicate sources of samples. Error bars indicate standard deviations. g HAc eq., grams of acetate equivalents. Other abbreviations are the same as those used in Table 4.

FIG. 3.

Dominant methanogens in different digesters observed as a function of ammonia or ammonium concentrations. Labels indicate sources of samples. Error bars indicate standard deviations. gN.L, grams of nitrogen per liter. Other abbreviations are the same as those used in Table 4.

FIG. 4.

Dominant methanogens in different digesters observed as a function of biogas production. Labels indicate sources of samples. d, day. Other abbreviations are the same as those used in Table 4.

Correlation between ammonia and organic acids.

Figure 5 shows inorganic nitrogen (ammonia or ammonium) versus organic acids for the various systems. Also shown is an apparent trend line for increasing organic acids with increasing ammonia. The sewage sludge digesters were within a region of low ammonia and VFA levels. There appeared to be a limit of approximately 1.5 kg of N m−3 of ammonia above which members of the Methanosarcinaceae dominated. Most thermophilic plants were consistent with the apparent trend line, but the mesophilic plants were more dispersed. The two systems with poor performance compared to the apparent trend line (i.e., above the trend line) were thermophilic and mesophilic manure digesters with only Methanosarcinaceae detected as the dominant methanogens. Three mesophilic reactors had better performance than would be expected from the apparent trend line. Two had Methanosarcinaceae as dominant organisms and Methanobacteriales as nondominant organisms; methanogenic communities in the other could not be identified and had moderate VFA levels under extreme inorganic nitrogen conditions.

FIG. 5.

Distribution of dominant methanogens as a function of organic acid versus ammonia or ammonium concentrations. Error bars indicate standard deviations. gHAceq, grams of acetate equivalents; kgN, kilograms of nitrogen. Other abbreviations are the same as those used in Table 4.

Comparative study of methanogenic diversity in biogas reactors and in the corresponding original inoculum.

In order to examine the effect of the original inoculum on the methanogenic diversity of the reactors, information was acquired regarding the origin of the inoculum used during the start-up of the reactors. For the purposes of this experiment, it was assumed that the methanogenic composition of the reactor containing the original inoculum had not changed between inoculation and sampling. Therefore, the changes described below also may have occurred after inoculation in the reactor containing the original inoculum.

The results shown in Table 5 indicated that a mesophilic manure-digesting plant (Revninge) and two WW sludge-digesting plants (Grindsted and Helsignor) had methanogenic compositions consistent with that of the inoculum sample. Four other manure-digesting plants (Studsgard, Snertinge, Nysted, and Lemvig) apparently changed dominant methanogens. The unidentified Archaea present in Sinding was not observed in the manure digester Lemvig, which was inoculated with a sample from Sinding. Similarly, the unidentified Archaea observed in Hashoj was not observed in Nysted, which was inoculated with a sample from Hashoj.

TABLE 5.

Methanogenic compositions in biogas reactors and methanogenic communities in reactors used as inoculum sources for those reactorsa

| Bioreactor location | Methanogenic composition of bioreactor | Source of inoculum | Methanogenic composition of inoculum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vegger | MS, MC | No exogenous inoculum | Natural contamination |

| Sinding | Unidentified Archaea | No exogenous inoculum | Natural contamination |

| Fangel | MS, MB, MG, MC | NI | |

| Lemvig | MB | Sinding | Unidentified Archaea |

| Hashoj | Unidentified Archaea | Cow manure from farm | |

| Studsgard | MS | Sinding | Unidentified Archaea |

| Snertinge | MS | Filskov and Hashoj | MC and Unidentified Archaea |

| Nysted | MS | Hashoj | Unidentified Archaea |

| Revninge | MS, MB, MG, MC | Fangel | MS, MB, MG, MC |

| Grindsted | MX | Haderslevb | MX |

| Fakse | MX, MS | NI | |

| Lundtofte | MX | No exogenous inoculum | Natural contamination |

| Hillerod | MX, MB | NI | |

| Helsignor | MX | Usserodb | MX |

| Sydkyst | MX | NI |

See Table 4, footnote a, for abbreviations; NI, no information.

Sludge-treating plant.

Enrichment and isolation bias.

Enrichments from Sinding, Grindsted, Lemvig, Vegger, and Fangel contained methanogens that were not observed in the corresponding raw samples, therefore demonstrating enrichment bias. Isolates of pure methanogenic cultures from enrichments were consistent with the original enrichments (data not shown). The exception was the H2-CO2 enrichment culture from Fangel, from which an unidentified Archaea could not be isolated.

DISCUSSION

In most instances, methanogenic diversity was broader in plants operating at mesophilic temperatures, a finding in agreement with previous reported data (24) based on thermophilic and mesophilic granular sludge. The dominance of members of the Methanosaetaceae in sludge digesters (Lundtofte, Helsignor, Hillerod, Fakse, Sydkyst, and Grindsted) is also in accordance with previous studies (18, 23). However, the presence of Methanosarcinaceae as dominant methanogens in manure digesters has never been well documented. There is only one study in which low levels of members of the Methanosarcinaceae and high levels of members of the Methanomicrobiales were detected in a full-scale manure-fed biogas plant by small-subunit rRNA sequence analysis (13). A comparison of the methanogenic diversities in biogas reactors and in the inoculum used for reactor start-up indicated that the original population was maintained only when an inoculum dominated by members of the Methanosaetaceae was used to start a WW sludge digester (two instances) or when an inoculum containing members of the Methanosarcinaceae was used to start a manure digester (one instance). This finding is probably related to the intolerance of members of the Methanosaetaceae for high ammonia levels. The findings from the inoculum examination support the notion that microbial compositions are mainly based on external conditions.

The loading rates of the studied systems, measured mainly on the basis of biogas production rates, did not appear to have an influence on the dominant methanogens. Concentrations of VFA and ammonia appeared to have the most influence. The presence of the strict aceticlastic methanogens of the Methanosaetaceae at low VFA and low ammonia levels is also in agreement with previous reported information (12, 16), indicating that acetate-utilizing methanogens are more sensitive to ammonia than are hydrogenotrophic methanogens. However, the other major acetate utilizers, members of the Methanosarcinaceae, were found to be the dominant methanogens at high ammonia concentrations—of up to 4.1 g of N liter−1.

It is difficult to conclude whether (i) the high free ammonia levels restrict Methanosaetaceae in favor of Methanosarcinaceae, members of which have a higher threshold for acetate (11, 22), and consequently cause higher levels of VFA; (ii) high free ammonia levels cause the accumulation of VFA, which then allow Methanosarcinaceae to outcompete Methanosaetaceae and restrict Methanosaetaceae; or (iii) manure digesters naturally have Methanosarcinaceae and sludge digesters naturally have Methanosaetaceae and also have high free ammonia and high VFA levels for some completely different reason. In our opinion, the most probable reason is the first one given above, and if manure digesters could be manipulated by, for example, reducing ammonia levels, members of the Methanosaetaceae should grow and reduce organic acid levels considerably.

Regarding the manure-digesting biogas plants, the trend line (Fig. 5) showed four outliers, three of which were mesophilic. It is difficult to draw conclusions with so few samples, but those with a more balanced ecology (Fangel and Revninge) or an unidentified methanogenic population (Hashoj) appeared to cope better with the high ammonia levels (in terms of the resulting organic acids). For this reason, it is important to further isolate and characterize the unidentified methanogens. Difficulty in the identification of the methanogens from the Hashoj and Sinding biogas plants could have been due to the limitations of visual in situ hybridization. FISH is very convenient for the rapid analysis of a large number of environmental samples but is limited when carried beyond the limits of oligonucleotide probes. ARC915 is an effective general probe, and order-level probes have been used in a wide range of systems; however, in complicated systems such as manure, they might fail to detect all methanogens. It should also be noted that many samples apparently without hydrogenotrophic methanogens may have contained significant numbers of members of the Methanobacteriales because the visual detection of those methanogens is difficult.

Enrichment bias (Table 4) may occur because enrichment procedures at defined temperatures and substrates are too selective for some methanogenic populations. This situation may limit the growth of the dominant microbe but favor the growth of another. It is very difficult to assess the best method for observing the most active microorganisms in mixed cultures from complex environments. Enrichment and isolation techniques are subject to bias, as observed here; FISH is dependent on responses to the probes used as well as sizes and physical characteristics; and ex situ DNA-RNA techniques are dependent on primers as well as extraction bias.

Acknowledgments

Nina Christensen (Technical University of Denmark) is gratefully acknowledged for assistance with the anaerobic roll-tube technique. Thanks are due to Majbrit Staun Jensen and Mona Refstrup for technical assistance with the experiments.

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Federation of European Microbiological Societies (FEMS), a Danish Government Scholarship, a UVE grant from the Danish Energy Agency, and grant B-MY 1208/02 from the Bulgarian National Fund for Scientific Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahring, B. K., I. Angelidaki, and K. Johansen. 1992. Anaerobic treatment of manure together with industrial waste. Water Sci. Technol. 25:211-218. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahring, B. K., M. Sandberg, and I. Angelidaki. 1995. Volatile fatty acids as indicators of process imbalance in anaerobic digestors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 41:559-565. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Public Health Association. 1985. Standard methods for the examination of waste and wastewater. American Public Health Association, Washington, D.C.

- 4.Angelidaki, I., and B. K. Ahring. 1994. Anaerobic thermophilic digestion of manure at different ammonia loads: effect of temperature. Water Res. 28:727-731. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angelidaki, I., S. P. Petersen, and B. K. Ahring. 1990. Effects of lipids on thermophilic anaerobic digestion and reduction of lipid inhibition upon addition of bentonite. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33:469-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batstone, D. J., J. Keller, I. Angelidaki, S. V. Kalyuzhnyi, S. G. Pavlostathis, A. Rozzi, W. T. Sanders, M. H. Siegrist, and V. A. Vavilin. 2002. Anaerobic digestion model no. 1 (ADM1). IWA, London, England. [PubMed]

- 7.Bhattacharya, S. K., and G. F. Parkin. 1989. The effect of ammonia on methane fermentation process. J. Water Pollut. Fed. 61:55-59. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dabert, P., J.-P. Delgenes, R. Moletta, and J.-J. Godon. 2002. Contribution of molecular microbiology to the study in water pollution removal of microbial community dynamics. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 1:39-42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daims, H., A. Bruhl, R. Amann, K.-H Schleifer, and M. Wagner. 1999. The domain-specific probe EUB338 is insufficient for the detection of all bacteria: development and evaluation of a more comprehensive probe set. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 22:434-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elferink, S. J. W. H., R. van Lis, H. G. H. J. Heilig, A. D. L. Akkermans, and A. J. M. Stams. 1998. Detection and quantification of microorganisms in anaerobic bioreactors. Biodegradation 9:169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferry, J. G. 1993. Methanogenesis: ecology, physiology, biochemistry and genetics. Chapman & Hall, New York, N.Y.

- 12.Garcia, J. L., B. K. C. Patel, and B. Ollivier. 2000. Taxonomic, phylogenetic, and ecological diversity of methanogenic archaea. Anaerobe 6:205-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen, K. H., B. K. Ahring, and L. Raskin. 1999. Quantification of syntrophic fatty acid-β-oxidizing bacteria in a mesophilic biogas reactor by oligonucleotide probe hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4767-4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hugenholtz, P., G. W. Tyson, and L. L. Blackall. 2002. Design and evaluation of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for fluorescence in situ hybridization. Methods Mol. Biol. 179:29-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hungate, R. E. 1969. A roll-tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes. Methods Microbiol. 3B:117-132. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koster, I. W., and G. Lettinga. 1984. The influence of ammonium-nitrogen on the specific activity of pelletized methanogenic sludge. Agric. Waste 9:205-216. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madigan, M., J. Martinko., and J. Parker. 2000. Brock's biology of microorganisms, 9th ed. Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

- 18.McMahon, K. D., P. G. Stroot, R. I. Mackie, and L. Raskin. 2001. Anaerobic codigestion of municipal solid waste and biosolids under various mixing conditions. II. Microbial population dynamics. Water Res. 35:1817-1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raskin, L., L. K. Poulsen, D. R. Noguera, B. E. Rittmann, and D. A. Stahl. 1994. Group-specific 16S rRNA hybridization probes to describe natural communities of methanogens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1232-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raskin, L., L. K. Poulsen, D. R. Noguera, B. E. Rittmann, and D. A. Stahl. 1994. Quantification of methanogenic groups in anaerobic biological reactors by oligonucleotide probe hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1241-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schink, B. 1997. Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:262-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt, J. E., Z. Mladenovska, M. Lange, and B. K. Ahring. 2000. Acetate conversion in anaerobic biogas reactors: traditional and molecular tools for studying this important group of anaerobic microorganisms. Biodegradation 11:359-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sekiguchi, Y., Y. Kamagata, K. Nakamura, A. Ohashi, and H. Harada. 1999. Fluorescence in situ hybridization using 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides reveals localization of methanogens and selected uncultured bacteria in mesophilic and thermophilic sludge granules. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 65:1280-1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sekiguchi, Y., Y. Kamagata, K. Syutsubo, A. Ohashi, H. Harada, and K. Nakamura. 1998. Phylogenetic diversity of mesophilic and thermophilic granular sludges determined by 16S rRNA gene analyses. Microbiology 144:2655-2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen, A. H., M. Winther-Nielsen, and B. K. Ahring. 1991. Kinetics of lactate, acetate and propionate in unadapted and lactate-adapted thermophilic, anaerobic sewage sludge: the influence of sludge adaptation for start-up of thermophilic UASB-reactors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34:823-827. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stahl, D. A., and R. Amann. 1991. Development and application of nucleic acid probes, p. 205-248. In E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (ed.), Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 27.Tafdrup, S. 1994. Centralized biogas plants combine agricultural and environmental benefits with energy production. Water Sci. Technol. 30:133-141. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolin, E. A., M. J. Wolin, and R. S. Wolfe. 1963. Formation of methane by bacterial extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 238:2882-2886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]