Abstract

We report the isolation of a keratinolytic-producing Bacillus subtilis strain and the characterization of the exceptional dehairing properties of its subtilisin-like keratinase. This enzyme can be an alternative to sodium sulfide, the major pollutant from tanneries, and may completely replace it. Its unique nonactivity upon collagen enhances its industrial potential.

Enzymatic dehairing in tanneries has been envisaged as an alternative to sulfides (4, 6, 9, 22, 23). Tanneries are constantly concerned about the obnoxious odor and pollution caused by the extremely toxic sodium sulfide used in the dehairing process step (24). Deaths due to this toxic chemical process have even been reported (2, 8). Worldwide, it is estimated that 315 million bovine leathers are produced per year. Considering a waste treatment cost of $0.30 per m2 of leather produced (A. Klein, personal communication), more than $1 million is spent per day to treat the waste from tanneries around the world. We report here a novel keratinase from Bacillus subtilis that has the potential to replace sodium sulfide in the dehairing process.

Microorganism isolation.

Bovine hair, skins wastes, and soil samples were suspended and cultivated in a feather-broth medium (composition in grams per liter: delipidated feather meal [the sole carbon and nitrogen source], 10.0; NaCl, 0.5; K2HPO4, 0.3; and KH2PO4, 0.4 [pH 7.5]).

The best keratinase-producing organism was identified as a B. subtilis strain (named strain S14) after classification based on homology (99%) of its 16S fragment with sequences from the NCBI databank by use of BLASTN 2.2.6 (1) (accession number AY345856).

Keratinase production.

The microorganism was cultivated in a 14-liter bioreactor in a culture medium composed of whey milk (a dairy byproduct containing 94.0% water, 5% lactose, 0.9% protein, and 0.1% fat), pH 8.5, and bovine hair (40 g/liter). A crude extract (supernatant) was obtained after centrifugation of the culture. Keratinolytic, subtilisin, and collagenase activities were assayed by using azokeratin, as described elsewhere (15). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that increases absorbance by 0.1 per hour in the conditions described above (15).

Dehairing assay.

A fresh fleshed bovine hide was washed with a commercial detergent solution and cut into 15- by 5-cm pieces. Two hundred grams of skin (usually two pieces) was processed in a drum flask at 4 rpm with crude extract or water (control) in a proportion of 1.0 ml of liquid per g of skin. When necessary, pH was adjusted with lime. At the end of the process, the skin pieces were gently scraped with fingers to remove loose hairs. This procedure was necessary because rubbing in this laboratory-scale process was not as vigorous as in industrial drums. Total skin depilation was observed in the pH range from 7 to 10, with 4.8 U/g of skin. A complete depilation was reached in 9 h at pH 9.0, 24°C, with 4.8 U/g of skin.

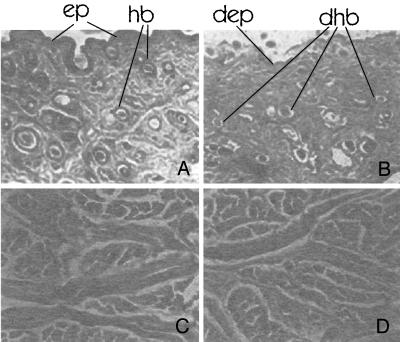

Samples of bovine skin were kept in contact with the crude extract, and the skin fragments were fixed as described by Prophet et al. (21) and examined by a light microscope. Comparing treated skins with untreated controls, we observed that only skin epidermis and adnexa, including hair bulbs, were digested, showing a histological autolytic-like appearance (Fig. 1A and B), as can be expected for proper skin depilation. In contrast, the collagen structure retained the same morphological aspect as the control (Fig. 1C and D), proving that the enzyme does not destroy or modify skin structure. As the dermis remains totally intact, this microorganism produces an enzyme with a high biotechnological potential.

FIG. 1.

Bovine skin treatment with the B. subtilis crude extract. (A) Control, water-treated skin (magnification, ×4); ep and hb indicate the epidermis and the hair bulb, respectively. (B) Skin after a 9-h treatment with crude extract (4.8 U/g of skin; magnification, ×4); dep and dhb indicate degraded epidermis and degraded hair bulb, respectively. (C) Control, water-treated skin during 24-h treatment (magnification, ×10). (D) Skin after a 24-h treatment with crude extract (4.8 U/g of skin; magnification, ×10).

Enzyme characterization.

The crude extract keratinase was purified by cation-exchange chromatography. Enzyme purity was demonstrated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (13), two-dimensional electrophoresis (10, 19), and capillary electrophoresis (12). The N-terminal sequence (determined by the Edman procedure) is AQSVPYGISQIKAPALHSQGYTGS----------VAVINSG (dashes indicate a gap in the sequence). Searches in sequence databases showed similarity between this sequence and sequences of several subtilisins.

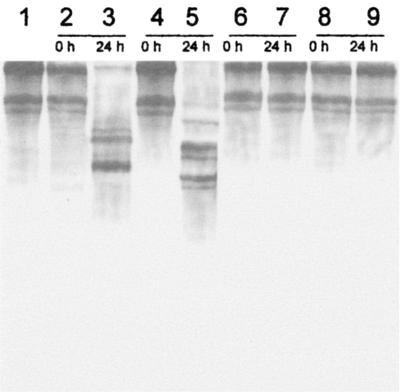

Calf skin collagen (1 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was incubated with 15 U (units calculated upon azokeratin substrate) of B. subtilis S14 crude extract/ml, purified keratinase, subtilisin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.), and, as a control, collagenase (Sigma) (20 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5, 24 h, 28°C). After incubation, no difference between negative controls, crude extract, and purified keratinase was detected (Fig. 2). Contrarily, collagen was degraded by subtilisin and collagenase. The inactivity upon collagen is a remarkable difference compared to all other known keratin-degrading enzymes, which hydrolyze collagen (3, 7, 11, 14, 15, 18). Indeed, damage to collagen gives unacceptable physical properties to the finished leather (9, 16, 23, 26). This enzyme opens the possibility to a direct introduction of enzymatic dehairing without changes in the time of the traditional tanning process (5, 17). Also, attaining dehairing at pH 8.0 is advantageous because it avoids high-pH effluents like those that occur in sulfide-using processes. Additionally, the use of this novel keratinase has the advantage of being a “hair-saving dehairing” process, allowing separation of the hair and avoiding the huge semigelatinous content and high level of organic matter in the wastewater caused by the sulfide “hair-destroying dehairing” methods (25). Other microorganisms able to produce dehairing enzymes, such as Aspergillus flavus (16, 22), Rhizopus oryzae (20), and another Bacillus sp. strain (23), need the use of the unpractical painting method. Also, dehairing with other enzymatic preparations still needs sodium sulfide (4, 6).

FIG. 2.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of the products resulting from the treatment of bovine collagen (1 mg) with 15 U (activity upon azokeratin) of several enzymes. Lane 1, collagen; lanes 2 and 3, subtilisin-treated collagen; lanes 4 and 5, collagenase-treated collagen; lanes 6 and 7, collagen treated with B. subtilis S14 supernatant; lanes 8 and 9, collagen treated with the pure keratinase. Samples were collected at 0 and 24 h of incubation.

For the first time, a new keratinase that is able to complete dehairing, using the worldwide dip method, but without sodium sulfide, has been described. The processing time, as well as the pH activity range and the avoidance of collagen damage, are properties that make this new enzyme an exceptional candidate for dehairing, as it fulfills the industry tanning requirements. Further studies are currently being done to evaluate this potential.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Wolf-Rainer Abraham, Daniela Regenhardt, and Jocelei Chies for help in sequence analysis. We especially thank Howard A. Junca for his very helpful suggestions on the manuscript and Lucélia Santi for her help in some experiments. Also, Beatriz Cámara, Cristiane B. Biehl, and Zulfe U. Biehl are thanked for carefully reading the manuscript.

This work was done with financial support from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tencológico (CNPq), Comissão de Aperfeiçoamento do Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped Blast and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasubramanian, S., and V. Pugalenthi. 2000. A comparative study of the determination of sulphide in tannery waste water by ion selective electrode (ISE) and iodimetry. Water Res. 34:4201-4206. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bressollier, P., F. Letourneau, M. Urdaci, and B. Verneuil. 1999. Purification and characterization of a keratinolytic serine proteinase from Streptomyces albidoflavus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2570-2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantera, C. S., A. R. Angelinetti, G. Altobelli, and G. Gaita. 1996. Hair-saving enzyme-assisted dehairing. Influence of enzymatic products upon final leather quality. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem. 80:83-86. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantera, C. S., V. D. Vera, N. Sierra, L. F. Crespo, and R. Escobar. 1995. Dehairing technology involving hair protection adaptation of a recirculation technique. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem. 79:12-17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassano, A., E. Drioli, R. Molinari, D. Grimaldi, F. La Cara, and M. Rossi. 2000. Enzymatic membrane reactor for eco-friendly goat skin dehairing. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem. 84:205-211. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chitte, R. R., V. K. Nalawade, and S. Dey. 1999. Keratinolytic activity from the broth of a feather-degrading thermophilic Streptomyces thermoviolaceus strain SD8. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28:131-136. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocheo, V. 1990. Impatto ambientale delle lavorazioni conciarie. Med. Lav. 81:230-241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George, S., V. Raju, M. R. V. Krishnan, T. V. Subramanian, and K. Jayaraman. 1995. Production of protease by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens in solid-state fermentation and its application in the dehairing of hides and skins. Process Biochem. 30:457-462. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Görg, A., W. Postel, and S. Günther. 1988. The current state of two-dimensional electrophoresis with immobilized pH gradients. Electrophoresis 9:531-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grzywnowicz, G., J. Lobarzewski, K. Wawrzkiewicz, and T. Wolski. 1989. Comparative characterization of proteolytic enzymes from Trichophyton gallinae and Trichophyton verrucosum. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 27:319-328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kist, T. B. L., C. Termignoni, and H.-P. H. Grieneisen. 1994. Capillary zone electrophoresis separation of kinins using a novel laser fluorescence detector. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 27:11-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, H., D. B. Suh, J. H. Hwang, and H. J. Suh,. 2002. Characterization of a keratinolytic metalloprotease from Bacillus sp. SCB-3. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 97:123-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, X., C. Lee, E. S. Casale, and J. C. H. Shih. 1992. Purification and characterization of a keratinase from a feather-degrading Bacillus licheniformis strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3271-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malathi, S., and R. Chakraborty. 1991. Production of alkaline protease by a new Aspergillus flavus isolate under solid-substrate fermentation conditions for use as a depilation agent. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:712-716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morera, J. M., E. Bartolí, M. D. Borrás, S. Góngora, and A. Marsal. 2000. Influence of the dehairing process on the mechanical characteristics of leather. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 95:293-300. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nam, G. W., D. W. Lee, H. S. Lee, N. J. Lee, B. C. Kim, E. A. Choe, J. K. Hwang, M. T. Suhartono, and Y. R. Pyun. 2002. Native-feather degradation by Fervidobacterium islandicum AW-1, a newly isolated keratinase-producing thermophilic anaerobe. Arch. Microbiol. 178:538-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Farrel, P. H. 1975. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 250:4007-4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pal, S., R. Banerjee, B. C. Bhattacharyya, and R. Chakraborty. 1996. Application of a proteolytic enzyme in tanneries as a depilating agent. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 91:59-63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prophet, E. B., B. Mills, J. B. Arrington, and L. H. Sobin. 1992. Laboratory methods in histotechnology, p. 279. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology, Washington, D.C.

- 22.Purushotham, H., S. Malathi, P. V. Rao, C. L. Rai, M. M. Immanuel, and K. V. Raghavan. 1994. Dehairing enzyme by solid state fermentation. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem. 80:52-56. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raju, A. A., N. K. Chandrababu, N. Samivelu, C. Rose, and N. M. Rao. 1996. Eco-friendly enzymatic dehairing using extracellular proteases from Bacillus species isolate. J. Am. Leather Chem. Assoc. 91:115-119. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roth, S. H., B. Skrajny, and R. J. Reiffenstein. 1995. Alteration of the morphology and neurochemistry of the developing mammalian nervous system by hydrogen sulphide. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 22:379-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valeika, V., J. Balèciûnienë, A. Beleðka, A. Skkrodenis, and V. Valeikienë. 1998. Lime-free dehairing: part 2. Influence of added salts on NaOH dehairing and on hide properties. J. Soc. Leather Technol. Chem. 82:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varela, H., M. D. Ferrari, L. Belobrajdic, A. Vásquez, and M. L. Loprena. 1997. Skin dehairing proteases of Bacillus subtilis: production and partial characterization. Biotechnol. Lett. 19:755-758. [Google Scholar]