Abstract

In the first year of a 1 peso per liter excise tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, there was a 6% reduction in purchases of taxed beverages in Mexico. This paper estimates changes in beverage purchases two years after tax implementation.

We used household store purchase data for 6,645 households from January 2012 to December 2015. Changes in purchases of taxed and untaxed beverages in the post-tax years were estimated using two separate models: comparing 2014 with predicted volumes (counterfactual) based on pre-tax (2012-2013) trends, and comparing 2015 with the same counterfactual.

Purchases of taxed beverages decreased by 8.2% over the two years on average (-5.5% in 2014; -9.7% in 2015). The lowest socioeconomic group had the largest decreases in taxed beverages in both years. Untaxed beverage purchases increased 2.1% in the post-tax period.

In Mexico, lower purchases of taxed beverages was sustained and grew in the second year of the tax.

Keywords: tax, sugar-sweetened beverages, Mexico

Introduction

In 2012, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Mexico reached 70% among adults and 30% among children (1, 2). Although obesity and all related chronic disease are the result of a multitude of causes, evidence shows that consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) is associated with weight gain, diabetes and other chronic diseases (3-8).

Added sugars in Mexico represent on average 12.5% of total energy intake (9). This is higher than the World Health Organization's recommended limit of added sugar intake at 10% or less (10). SSB alone account for 70% of added sugar in Mexico (9.8% of total energy intake on average (11), and therefore SSB is a logical target for lowering added sugar intake.

To reduce the consumption of SSB, the Mexican government implemented an excise tax of 1 Mexican peso per liter to all non-alcoholic beverages with added sugar (including powdered SSB based on their reconstitution and flavored/sweetened dairy products that are not milks) starting on 1st January 2014 (12). The regulation allows for the tax to be adjusted when the cumulative inflation rate in Mexico reaches 10% (13).

Earlier evidence for 2014 showed that in urban areas, the tax passed completely to prices on average, and there were no significant changes in prices of untaxed beverages, except for diet sodas whose price increased but represent a low proportion of untaxed beverages (14) and that on average, there was a 6% decline in purchases of taxed beverages and a 4% increase in untaxed beverages purchases in 2014 (15).

After these initial peer reviewed research papers were published, there were statements in the press claiming that the SSB tax did not reduce purchases of these products in 2015 (16), as it did in 2014. Subsequent investigations into the approaches used by these groups reveal that they used aggregate sales measures, ignored significant increases in population size, changes in age composition, among other problems (17-19).

A few studies have already noted that when one adjusts for these various factors aggregate sales per capita show a decline in the second year of the tax (17-19); however these data do not provide the rigorous analysis needed to understand how households overall and of various socioeconomic groups respond to the tax. In addition, these analyses cannot account for other critical factors that might affect household beverage purchases. It is also important to note that because the cumulative Mexican inflation rate has not reached 10% (cumulative inflation over the two years was 6.3%)(20)-a level which triggers an inflation adjustment as noted above-, it is possible that the gradual effects of inflation eroded the tax value over time. Also, it is possible that over a longer period of time, some Mexican households adjusted their basket of purchases to allow them to increase SSB purchases (21) or, on the contrary, by habit formation people could reduce consumption more in the long run than in the short run (22).

Although some countries/cities have proposed or implemented taxes to SSB (France, Finland, Mexico, Colombia, South Africa, the United Kingdom as well as some cities in the US such as Berkeley, Albany, San Francisco, Oakland, California; Boulder, Colorado; Cook county, Illinois) evidence of changes in purchases or consumption is scarce. Recent results from the short term changes in SSB intake in Berkeley show a reduction in the frequency of consumption among lower income households (23).

This paper attempts to control for many of these critical issues by conducting a longitudinal analysis of a panel of Mexican urban households to estimate changes in purchases from stores of taxed and untaxed beverages two years after the implementation of the SSB tax. We analyzed the change by socioeconomic group and by beverage categories.

Methods

Data

We used monthly household store purchase data from Nielsen's Mexico Consumer Panel Services between January 2012 and December 2015 that includes a sample of 6,645 households in Mexico living in 53 cities, representing cities that have populations from 50,000 to 8.9 million inhabitants. For each household in the survey, the data include information on food and beverages purchased from stores and socio-demographic variables. Data collection on purchases is based on information that households have to keep: receipts from purchases in stores, empty packages of food and beverages purchased and daily reports/diaries. Therefore, information contains beverage purchases from a variety of stores, markets and any other vendors so long as it has a barcode and or packaging that provides information about the product (e.g., brand, size). The data do not include information on fountain drinks or hot drinks from food service locations or potable/tap water consumed.

We systematically classified products into beverage categories in 2016 based on product descriptions and sources available on the internet and in stores. In this study we focus on taxed and untaxed beverages. The two categories for taxed beverages were carbonated sodas and non-carbonated SSBs (including powders in its reconstituted form based on the label), and the three categories for untaxed beverages were carbonated drinks such as diet sodas; sparkling, still, or plain water; unsweetened dairy beverages and substitutes, and other untaxed drinks, including unsweetened fruit juices. From these we summed the monthly volume each household purchased in each of the beverage categories across each of the 48 months. Then we calculated the volume per capita per day for interpretability.

Empirical estimation

We used the same model employed to evaluate changes in purchases in 2014 (15) with two adjustments. First, the model now controls for inflation, which is relevant for the medium term evaluation, as the tax has not been adjusted for inflation yet. Second, the new approach estimates the association of the tax and purchases in two separate models for each of the post-tax years to allow comparisons to the pre-tax period. The separate models also ensure that the additional 2015 data does not bias the predicted values (up or down).

We model changes in monthly volume of purchases (ml/capita/day) of taxed and untaxed beverages. The Consumer Panel Services did not collect information on purchases of dairy products from the full sample before October 2012 (personal communication); therefore, we excluded data for dairy beverages (untaxed) in order to have comparable time periods for taxed and untaxed beverages. Estimations for untaxed beverages including dairy are presented in the supplemental material. We log transformed the dependent variable as the distribution of purchases was skewed and was not normally distributed. All non-purchases were kept when log transforming by adding a small value of 1 ml/capita/day to all zero purchases.

Non-reported of purchase of products within a beverage category can occur due to misreporting. This variability in the probability of missing purchase data, needs to be accounted for. For each beverage category with more than 10% household reporting no purchases (taxed sodas, taxed non-soda SSBs, taxed dairy beverages, untaxed water, untaxed diary and other untaxed beverages), we first ran longitudinal probit models for the probability of reporting purchasing (or the probability of missing data). We derived the inverse probability weights (IPW), as the inverse of the predicted values from these models. Thus, higher IPWs are given to household-month observations with lower probability of reporting purchasing so that these under-represented observations are appropriately reflected in the analyses. The IPWs are included in the fixed effects model to predict changes in purchases using areg, absorb in Stata (24) as IPWs can change over time for any given household.

We estimated fixed effects regression adjusting for variables that change with time: annual measures of socio-demographic characteristics of the households (household size and composition, education of the head of the household and three groups of socioeconomic status) and macroeconomic variables such as state quarterly unemployment rates (25), minimum daily salary (26). We adjusted for monthly inflation using the consumer price index from prices collected in 46 cities in Mexico (20) for each corresponding year, month and city (or city in the same state). We also included month dummies to adjust for seasonality instead of quarters as previously estimated (BMJ), to better represent the seasonality, particularly for certain months (December 2014- Feb 2015), when a decline was significantly larger than observed in previous years, particularly for untaxed beverages.

We ran separate models for each post-tax year using the pre-tax period for comparison with both post-tax years: model 1 compares 2012-2013 with 2014; model 2 compares 2012-2013 with 2015. Within each model, we compared the predicted post-tax volume of beverages purchased obtained from the model with the predicted volume that would have been if the tax was not implemented from pre-tax trends (the counterfactual). The counterfactual for each year was predicted from replacing the dummy variable for the tax with zero for all observation but allowing all other observed variables (including all other time measures) to vary. We conducted the analysis for the full sample and stratified the model by socioeconomic status and type of beverage (taxed sodas, taxed non-soda SSB, taxed dairy beverages, still bottled water, untaxed dairy beverages and other untaxed beverages).

The analytical sample for this study included 270,782 households-month observations for the period between January 2012 and December 2015 from 6,645 households (average of 40.7 months of data per household out of the maximum of 48.

There are some limitations to this research. As in all non-experimental studies, causality cannot be established as other changes are occurring concurrent with the tax. We attempted to overcome this by adjusting for contextual economic factors and time trends, but while these adjustments make the results more plausible, they may have been insufficient. Another aspect to consider is the concurrent introduction of an 8% ad valorem tax to nonessential energy dense food that has shown to be associated with purchases (27). It is also possible that differential changes in purchases of taxed beverages may result not only due to the elastic nature of the demand for SSB, but it could also be the result of more awareness about the negative effect of SSBs on health (10) and of recommendations by WHO/PAHO to reduce the intake of SSBs through taxes and other policies (28) or the potential effect of other regulations implemented by the Government such as the regulation of unhealthy food and beverages in schools and partial regulation of marketing targeted to children (29, 30). Conversely, an increase in industry strategies (campaigns, promotions, marketing) in the post-tax period (31) may have attenuated the true independent effect of the tax.

Other limitations include the incomplete data on dairy beverage purchases before October 2012, limiting the overall effect of the tax on untaxed beverage purchases. Also, the data only represents consumers in cities with more than 50,000 residents; we do not have data from smaller cities and rural areas.

Finally, average purchases in household surveys tend to be underestimated compared to other sources. For example, the average per capita purchase per day of taxed beverages in the purchase data in 2012 was 224.7ml compared to 345.2ml in Euromonitor (off-trade sales, which measures sales from stores and excludes food service sales such as from fountain drinks)(32). However, the trends in underreporting comparing Nielsen food purchase and Euromonitor data between 2012 and 2015 did not change over time.

Results

Descriptive results

Appendix exhibits A1 and A2 in the supplemental materials shows the monthly weighted unadjusted mean for taxed beverages and untaxed beverages (excluding dairy) from January 2012 to December 2015 (33).

Meanwhile, Appendix exhibit A3 of the supplemental material compares the survey weighted measures for head of the household education and region between the Nielsen Consumer Panel Service and the nationally representative National Income and Expenditure Survey and population projections for 2014 (33).

Adjusted analyses of purchases

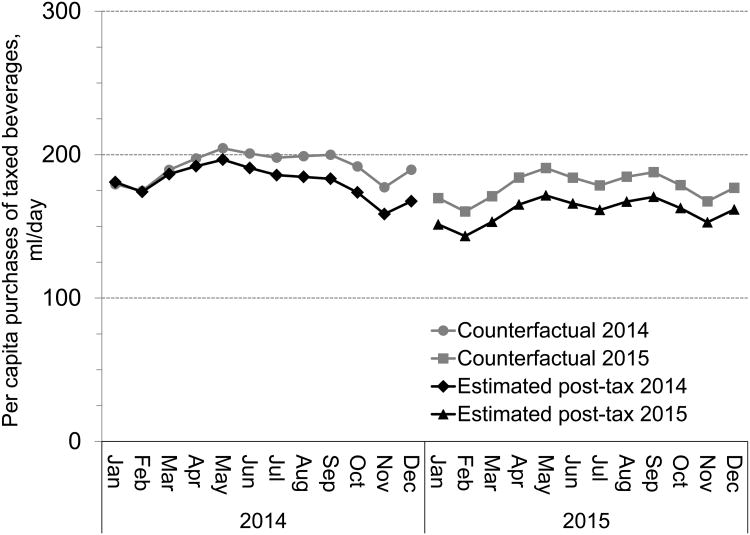

Exhibit 1 shows the adjusted predicted and counterfactual values for 2014 and 2015 from the two separate models for taxed beverages. Results show an average decline in taxed beverages of -5.5% in 2014, and -9.7% in 2015 compared to the counterfactual, resulting in an average decline of -7.6% for the entire post-tax period (exhibit 2 shows the relative values (%) for all months).

Exhibit 1. Absolute values (ml/capita/day) of counterfactuals (predicted in the absence of the tax) and post-tax volumes of taxed beverages.

Source: Authors' own analyses and calculations based on data from Nielsen though its Mexico Consumer Panel Service (CPS) for the food and beverage categories for January 2012–December 2015 (The Nielsen Company, 2016). Nielsen is not responsible for and had no role in preparing the results reported herein.

Notes: Models adjusted for household size and composition, seasonality, education of the head of the household, household socioeconomic status and macroeconomic variables. Monthly counterfactual estimated based on pre-tax trends.

Differences in absolute values comparing the post-tax periods with the counterfactuals were all statistically significant at p<0.01.

Exhibit 2. Monthly relative differences (%) between counterfactuals (predicted in the absence of the tax) and post-tax volumes of taxed beverages and untaxed beverages excluding dairy.

| Month/year | Taxed beverages | Untaxed beverages excluding dairy |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | ||

| January | -0.8%* | 10.2%* |

| February | -0.4%* | 9.3%* |

| March | -1.6* | 8.4%* |

| April | -2.7%* | 7.5%* |

| May | -3.9%* | 6.6%* |

| June | -5.0%* | 5.7%* |

| July | -6.1%* | 4.8%* |

| August | -7.3%* | 3.9%* |

| September | -8.4%* | 3.1%* |

| October | -9.4%* | 2.2%* |

| November | -10.5%* | 1.4%* |

| December | -11.6%* | 0.5%* |

| 2014 Average | -5.5% | 5.3% |

|

| ||

| 2015 | ||

| January | -10.8%* | -4.4%* |

| February | -10.6%* | -3.8%* |

| March | -10.4%* | -3.2%* |

| April | -10.2%* | -2.6%* |

| May | -10.0%* | -2.0%* |

| June | -9.8%* | -1.3%* |

| July | -9.6%* | -0.7%* |

| August | -9.4%* | -0.1%* |

| September | -9.2%* | -0.5%* |

| October | -9.0%* | 1.2%* |

| November | -8.8%* | 1.8%* |

| December | -8.5%* | 2.4%* |

| 2015 Average | -9.7% | -1.0% |

| Average 2014-2015 | -7.6% | 2.1% |

Source: Authors' own analyses and calculations based on data from Nielsen though its Mexico Consumer Panel Service (CPS) for the food and beverage categories for January 2012–December 2015 (The Nielsen Company, 2016). Nielsen is not responsible for and had no role in preparing the results reported herein.

Notes: Models adjusted for household size and composition, seasonality, education of the head of the household, household socioeconomic status and macroeconomic variables. Monthly counterfactual estimated based on pre-tax trends.

Relative difference in month A =(adjusted observed volume in month A–counterfactual volume in month A)*100%/counterfactual volume in month A)

Differences in absolute values comparing the post-tax periods with the counterfactuals were statistically significant at p<0.01.

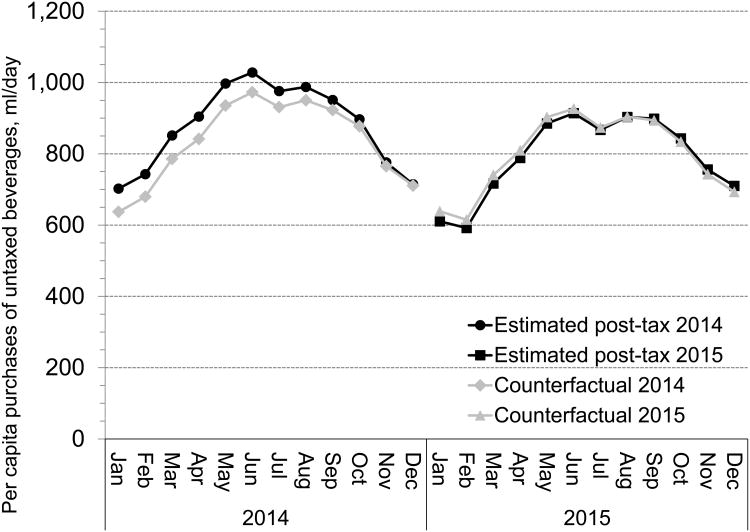

Exhibit 3 shows the adjusted predicted and counterfactual values for 2014 and 2015 from separate models for untaxed beverages. Results show an increase in untaxed beverage purchased of 5.3% in 2014 and -1.0% in 2015, which gives an average increase of 2.1% in the entire post-tax period (exhibit 4 shows the relative values (%) for all months).

Exhibit 3. Absolute values (ml/capita/day) of counterfactuals (predicted in the absence of the tax) and post-tax volumes of untaxed beverages excluding dairy.

Source: Authors' own analyses and calculations based on data from Nielsen though its Mexico Consumer Panel Service (CPS) for the food and beverage categories for January 2012–December 2015 (The Nielsen Company, 2016). Nielsen is not responsible for and had no role in preparing the results reported herein.

Notes: Models adjusted for household size and composition, seasonality, education of the head of the household, household socioeconomic status and macroeconomic variables. Monthly counterfactual estimated based on pre-tax trends.

Differences in absolute values comparing the post-tax periods with the counterfactuals were all statistically significant at p<0.01. Excludes dairy beverages due to incomplete data from Jan -September 2012.

Exhibit 4. Absolute (ml/capita/day) and relative differences (%) between counterfactuals and post-tax volumes of taxed and untaxed beverage purchases stratified by SES.

| SES Level | 2014 | 2015 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxed Beverages | |||

| Lowest | |||

| Absolute difference | -18.8* | -29.3* | -24.0 |

| Relative difference | -9.0% | -14.3% | -11.7% |

| Middle | |||

| Absolute difference | -12.8* | -23.3* | -18.0 |

| Relative difference | -5.9% | -11.7% | -8.8% |

| Highest | |||

| Absolute difference | -6.9* | -8.2* | -7.6 |

| Relative difference | -4.4% | -5.6% | -5.1% |

| All | |||

| Absolute difference | -10.6* | -17.2* | -13.9 |

| Relative difference | -5.5% | -9.7% | -7.6% |

|

| |||

| Untaxed Beverages | |||

| Lowest | |||

| Absolute difference | 15.9* | -46.3* | -15.2 |

| Relative difference | 2.4% | -5.9% | -1.8% |

| Middle | |||

| Absolute difference | 48.5* | -8.8 | 19.9 |

| Relative difference | 5.6% | -1.2% | 2.1% |

| Highest | |||

| Absolute difference | 39.1 | -11.9 | 13.6 |

| Relative difference | 4.5% | -1.5% | 1.2% |

| All | |||

| Absolute difference | 43.2 | -7.0 | 18.1 |

| Relative difference | 5.3% | -1.0% | 2.1% |

Source: Authors' own analyses and calculations based on data from Nielsen though its Mexico Consumer Panel Service (CPS) for the food and beverage categories for January 2012–December 2015 (The Nielsen Company, 2016). Nielsen is not responsible for and had no role in preparing the results reported herein.

Notes: Models adjusted for household size and composition, seasonality, education of the head of the household, household socioeconomic status and macroeconomic variables. Counterfactual estimated based on pre-tax trends.

Differences in absolute values comparing the post-tax periods with the counterfactuals were all statistically significant at p<0.01.

excludes dairy beverages due to incomplete data from Jan -September 2012.

Exhibit 4 shows the absolute and relative difference in adjusted volumes of taxed and untaxed beverages in the post-tax period compared to the counterfactual by socioeconomic status. For taxed beverages, all groups experienced significant declines but reductions in absolute and relative terms were larger among the lowest socioeconomic group (-18.8 ml/day/capita, -9.0% in 2014 and -29.3ml/day/capita, -14.3% in 2015) compared to the middle and highest socioeconomic groups. The differences between socioeconomic groups are statistically significant (confidence intervals do not overlap). For untaxed beverages, the middle socioeconomic group had the largest positive increase in purchases in 2014. Overall untaxed beverage purchases fell slightly in year 2, such that the overall increase over the 2 post-tax years was only 2.1%

Appendix exhibit 4 of the supplemental material presents the results of the model for untaxed beverages including dairy (33).

Appendix exhibit A5 shows the results of changes in purchases for taxed and untaxed beverages by type of beverage (33).

Conclusions

We estimated changes in purchases of taxed and untaxed beverages two years after the SSB excise tax was implemented in Mexico. For taxed beverages, we found an average decline of -7.6% in purchases over the two post-tax years compared to what would have happened if the tax were not implemented. The reduction was larger in 2015 compared to 2014 (-9.7% and -5.5%, respectively). For untaxed beverages we found an average increase of 2.1% over the two post-tax years. Similar to previously published findings for 2014 (13), all three socioeconomic groups studied reduced purchases of taxed beverages in 2015, but absolute and relative reductions were larger among the households in the low socioeconomic status.

Although the model presented in this paper adjusted for inflation and included monthly dummies for seasonality, results for taxed beverages are very similar compared to previous findings for just 2014 alone (15). Results for the two years are very similar to a recent analysis using sales data from the Monthly Surveys of the Manufacturing Industry that shows a 7.3% reduction in sales of SSB two years after the implementation of the tax compared to 2007-2013 (19). Although sales data are less likely to underestimate actual consumption, the data used in the current study allows a better classification of taxed and untaxed beverages and the possibility to adjust and stratify for variables at the household level that are associated with purchases. These findings provide empirical evidence to model-based price elasticity studies of SSB demand in the United States showing higher price elasticity in the long run compared to the short run (22). Economics studies of tobacco and other highly preferred habit-forming items where research imply that the long-term impact of a price change will be much larger than the short-term effect for tobacco, alcohol and illicit drugs (34-38). The higher reduction in purchases in the second year of the tax suggests that this may be true for SSB purchases also.

We found that taxed sodas had a very small decline compared to non-soda SSBs, which was consistent with the first year results (15). These findings could partly be explained by the higher prices and higher price elasticities of non-soda SSBs compared to sodas (39). Consumers may have substituted for cheaper sodas given their large price variations (14). Moreover, the reduction in purchases of taxed sodas beverages may be underestimated if purchases of smaller package sizes (which showed a larger increase in price than larger packages after the tax) are not well reported in the data, as these may be consumed on the go and thus may be underreported by the key household informant as is true for diet surveys also.

For untaxed beverages excluding dairy, previous findings showed a 2% increase in 2014 (15), which was lower than the 5.3% increase shown in this paper. The difference is that in the former study, dairy and other untaxed beverages were excluded and in this paper only dairy was the category excluded because data was collected only since October 2012. Other beverages represent about 5% of total untaxed beverage purchases and show a large increase in the post-tax period as shown in Table S2.

We found a drop for untaxed beverages in 2015, mainly linked to a very large decrease in purchases of untaxed beverages the Dec 2014-Feb 2015 period. In contrast, aggregated per capita sales data for the country shows an increasing trend of non-SSB beverages since 2001 that continued through 2015 (32). In addition, analyses of the Monthly Surveys of the Manufacturing Industry show an increase in the production sales of still bottled water of 5.2% in the post-tax period compared to 2007-2013, which may reflect that consumers in Mexico are substituting for non-SSBs such as water (19). Each data sources has its limitations, which may be the cause of the discrepancies between aggregate per capita sales data per capita and information on purchases from the panel. Analysis of future years of data may clarify the discrepancy.

Overall these results contradict industry reports of a decline in the effect of the tax after the first year of implementation. We show that there was a further reduction in SSB purchases in 2015 beyond the reduction in 2014. Moreover, both the absolute and relative reduction was highest among lower socioeconomic households. Future analysis of a national nutrition survey conducted in 2016 will allow us to understand shifts in a number of cardiometabolic measures between 2012 and 2016 as well as examine shifts in dietary patterns. Together with further future analyses of food purchase data these analyses will provide a better understanding of the longer term implications of the Mexican SSB excise tax.

International Agencies such as the World Health Organization and the Pan American Health Organization have recommended implementing taxes to discourage the consumption of unhealthy food and beverages though increases in relative prices (28, 40). The results of the evaluation of the tax in Mexico revealed reductions in SSB purchases of 8.2% on average over the first two years. These reductions in consumption could have positive impacts on health outcomes and reductions in health care expenses as shown in a recently published simulation model (41). Decreases in purchases were higher among households of lower socioeconomic status which could lead to higher health care savings for the country as well as for individuals. Given this sustained effect of the tax on purchases and based on results showing that responses to prices of cigarettes (price elasticities) monotonically increase with prices (42, 43), higher impacts could be achieved by increasing the tax at least to 2 pesos/liter (20% increase in price). Internationally, findings from Mexico can encourage other countries to use fiscal policies to reduce the consumption of unhealthy options along with other interventions to reduce the burden of chronic diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Donna Miles for exceptional assistance with the data management. We also thank the very helpful comments from Frank Chaloupka and Harold Alderman from our evaluation advisory committee.

Sources of Support: This support comes primarily from the Bloomberg Philanthropies (grants to University of North Carolina and to the Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública), with support from the NIH R01DK108148, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant 71698), and the Carolina Population Center and its NIH Center grant (P2C HD0550924). Funders had no direct role in the study design, analysis or manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have conflict of interests of any type with respect to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Barquera S, Campos-Nonato I, Hernandez-Barrera L, Pedroza A, Rivera-Dommarco JA. Prevalence of obesity in Mexican adults 2000-2012. Salud publica de Mexico. 2013;55(2):S151–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rivera JA, de Cossio TG, Pedraza LS, Aburto TC, Sanchez TG, Martorell R. Childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity in Latin America: a systematic review. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2014;2(4):321–32. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes care. 2010;33(11):2477–83. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):274–88. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. Bmj. 2013;346:e7492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vartanian LR, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of public health. 2007;97(4):667–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.083782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez-Escamilla R, Obbagy JE, Altman JM, Essery EV, McGrane MM, Wong YP, et al. Dietary energy density and body weight in adults and children: a systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2012;112(5):671–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Cancer Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Pimienta TG, Batis C, Lutter CK, Rivera JA. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Are the Main Sources of Added Sugar Intake in the Mexican Population. J Nutr. 2016;146(9):1888S–96S. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.220301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Geneva. 2015 [November 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/sugars_intake/en/ [PubMed]

- 11.Aburto TC, Pedraza LS, Sanchez-Pimienta TG, Batis C, Rivera JA. Discretionary Foods Have a High Contribution and Fruit, Vegetables, and Legumes Have a Low Contribution to the Total Energy Intake of the Mexican Population. J Nutr. 2016;146(9):1881S–7S. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.219121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Secretaría de Gobernació. L ey del Impuesto Especial sobre Producción y Servicios [Excise Tax Law for Production and Services] Mexico City. 2013 [Nov 2016]. Available from: http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5325371&fecha=11/12/2013.

- 13.Secretaría de Gobernación. Código Fiscal de la Federación [Fiscal Federation Code] Mexico. 2004 [November 2016]. Available from: http://info4.juridicas.unam.mx/ijure/fed/6/28.htm?s=

- 14.Colchero MA, Salgado JC, Unar-Munguia M, Molina M, Ng S, Rivera-Dommarco JA. Changes in Prices After an Excise Tax to Sweetened Sugar Beverages Was Implemented in Mexico: Evidence from Urban Areas. PloS one. 2015;10(12):e0144408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colchero MA, Popkin BM, Rivera JA, Ng SW. Beverage purchases from stores in Mexico under the excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages: observational study. The BMJ. 2016;352:h6704. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guthrie A, Esterl Mike. Despite Tax, Mexico Soda Sales Pop --- Two years after a levy of about 10% sparked a decline, the numbers are rising once again. Wall Street Journal. 2016 May 4; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. Why it is not possible to make determinations on the usefulness of the tax on sugar sweetened beverages in Mexico during 2015 using raw sales data. 2016 Available from: https://www.insp.mx/epppo/blog/4063-tax-sugar-sweetened-beverages.html.

- 18.Cherukupalli R. Growth rates and aggregates: bringing data to the soda wars. The Lancet Global Health Blog [Internet] 2016 Available from: http://globalhealth.thelancet.com/2016/06/10/growth-rates-and-aggregates-bringing-data-soda-wars.

- 19.Colchero MA, Guerrero-Lopez CM, Molina M, Rivera JA. Beverages Sales in Mexico before and after Implementation of a Sugar Sweetened Beverage Tax. PloS one. 2016;11(9):e0163463. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Indice Nacional de Precios al Consumidor [National Consumer Price Index] 2016 [November 2016]. Available from: http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/inp/default.aspx.

- 21.Leicester A, Level P LR. Tax and benefit policy: insights from behavioral economics. The Institute for Fiscal Studies; London: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhen C, Wohlgenant M, Karns S, Kaufman P. Habit formation and demand for sugar-sweetened beverages. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 2010;22 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falbe J, Thompson HR, Becker CM, Rojas N, McCulloch CE, Madsen KA. Impact of the Berkeley Excise Tax on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption. American journal of public health. 2016;106(10):1865–71. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCopr LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo [National Occupation and Employment Survey] Mexico. [cited April 2016];2007-2015 Available from: http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/Proyectos/encuestas/hogares/regulares/enoe.

- 26.Comisión Nacional de los salarios mínimos. Tabla de salarios mínimos generales y profesionales por áreas geográficas [Minimum wages: general and professional by geogrpahic location] 2015 Available from: www.conasami.gob.mx/t_sal_mini_prof.html.

- 27.Batis C, Rivera JA, Popkin BM, Taillie LS. First-Year Evaluation of Mexico's Tax on Nonessential Energy-Dense Foods: An Observational Study. PLoS medicine. 2016;13(7):e1002057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan American Health Organization. Plan of Action for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Washington, D.C: 2014. [November 2016]. Available from: http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11373%3Aplan-of-action-prevention-obesity-children-adolescents&catid=4042%3Areference-documents&Itemid=41740&lang=en. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gobierno de la República. Estrategia Nacional para la Prevención y el Control del Sobrepeso, la Obesidad y la Diabetes [National Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Overweight, Obesity and Diabetes] México: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Théodore FL, Tolentino-Mayo L, Hernández-Zenil E, Bahena L, Velasco A, Popkin B, et al. Pitfalls of the self-regulation of advertisements directed at children on Mexican television. Pediatr Obes. 2016:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública. Estrategias de mercadotecnia de la industria de bebidas azucaradas [Marketing strategies of the beverage industry] 2016 Available from: https://www.insp.mx/epppo/blog/3811-estrategias-industria-bebidas.html.

- 32.Euromonitor. Euromonitor International's Passport Global Market. [cited 2013];2015 Available from: http://www.euromonitor.com/

- 33.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 34.Jensen JD, Smed S. The Danish tax on saturated fat – Short run effects on consumption, substitution patterns and consumer prices of fats. Food Policy. 2013;42(0):18–31. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becker GS, Murphy KM. A theory of rational addiction. J Polit Econ. 1988;96(4):675–700. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossman M, Chaloupka, Frank J. The demand for cocaine by young adults: a rational addiction approach. J Health Econ. 1998;17(4):427–74. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(97)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gruber J, Koszegi B. Is addiction “rational”? Theory and evidence. Q J Econ. 2001;116(4):1261–303. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guindon GE, Paraje GR, Chaloupka FJ. The impact of prices and taxes on the use of tobacco products in Latin America and the Caribbean. American journal of public health. 2015;105(3):e9–19. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colchero MA, Salgado JC, Unar-Munguia M, Hernandez-Avila M, Rivera-Dommarco JA. Price elasticity of the demand for sugar sweetened beverages and soft drinks in Mexico. Econ Hum Biol. 2015;19:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Fiscal policies for diet and prevention of noncommuicable diseases: technical meeting report. Geneva: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchez-Romero LM, Penko J, Coxson PG, Fernandez A, Mason A, Moran AE, et al. Projected Impact of Mexico's Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax Policy on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: A Modeling Study. PLoS medicine. 2016;13(11):e1002158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tauras JA, Pesko MF, Huang J, Chaloupka F, Farrely MC. The effect of cigarrete prices on cigarette sales: exploring heterogeneity in price elasticities at high and low prices. NBER Working Paper Series. 2016 Working Paper 22251. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pesko MF, Tauras JA, Huang J, Chaloupka F. The influence of geography and measurement in estimating cigarette price resposiveness. NBER Working Paper Series. 2016 Working Paper 22296. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.