Abstract

Early onset torsion dystonia is an autosomal dominant movement disorder of variable caused by a glutamic acid, i.e. ΔE, deletion in DYT1, encoding the protein torsinA. Genetic and structural data implicate basal ganglia dysfunction in dystonia. TorsinA, however, is diffusely expressed, and therefore the primary source of dysfunction may be obscured in pan-neuronal transgenic mouse models. We utilized the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) promoter to direct transgene expression specifically to dopaminergic neurons of the midbrain to identify cell-autonomous abnormalities. Expression of both the human wild type (hTorsinA) and mutant (ΔE-hTorsinA) protein resulted in alterations of dopamine release as detected by microdialysis and fast cycle voltammetry. Motor abnormalities detected in these mice mimicked those noted in transgenic mice with pan-neuronal transgene expression. The locomotor response to cocaine in both TH-hTorsinA and TH-ΔE-hTorsinA, in the face of abnormal extracellular DA levels relative to non-transgenic mice, suggests compensatory, post-synaptic alterations in striatal DA transmission. This is the first cell-subtype-specific DYT1 transgenic mouse that can serve to differentiate between primary and secondary changes in dystonia, thereby helping to target disease therapies.

Keywords: dystonia, tyrosine hydroxylase, dopamine, DYT1, torsinA, striatum, microdialysis, voltammetry

INTRODUCTION

Early onset torsion dystonia (EOTD) is an autosomal dominant movement disorder of variable penetrance due to a GAG (glutamic acid, i.e. ΔE) deletion in DYT1, the gene that encodes the protein torsinA (Ozelius et al., 1997). As torsinA expression is diffuse within the central nervous system and peripheral organs (Ozelius et al., 1997), the source of primary dysfunction is obscured. Implicating dysfunction within the basal ganglia, however, is the fact that numerous clinical conditions presenting during the pediatric period with motor manifestations similar to EOTD, are associated with damage or degeneration within these nuclei. Basal ganglia dysfunction has been examined in several mouse models of EOTD (reviewed in Granata et al., 2009), but data interpretation has been complicated by the widespread expression, knock-in, knock-down, or knock-out of the gene, making it difficult determine the effects of the mutated protein on specific cell populations within the complex basal ganglia circuitry.

A key component of basal ganglia circuitry is the nigrostriatal dopamine (DA) pathway, which projects from the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) to the dorsal striatum. TorsinA is expressed in SNpc DA neurons and their axonal projections in the striatum, but its expression is not enriched in those somata (Shashidharan et al., 2000; Konakova and Pulst, 2001; Augood et al., 2003). TorsinA is a member of the AAA+ ATPase family of proteins, which are chaperones that interact with, and alter the conformation of, other proteins (Breakefield et al., 2001, 2008 and Granata et al., 2009 for review). TorsinA interactors include snapin, kinesin light chain 1, nuclear envelope protein LAP1, endoplasmic reticulum LULL1, and nesprins, suggesting multiple roles for torsinA, such as vesicle recycling, neurotransmitter release and re-uptake, protein processing, neuronal protection, cell adhesion, neurite extension, nuclear envelope function and cytoskeletal linkage (Hewett et al., 2006; Goodchild et al., 2005; Muraro and Moffat, 2006; Balcioglu et al., 2007; Granata et al., 2008; Cao et al., 2005; Torres et al., 2004; Nery et al., 2008). Interference with these normal functions of torsinA might compromise dynamic DA signaling in the nigrostriatal pathway.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest a role for abnormalities of the DA system in the pathophysiology of dystonia (reviewed in Wichmann, 2008). Previous studies in torsinA transgenic and knockdown mice have shown alterations in striatal levels of DA and/or its metabolites (Dang et al 2005, 2006; Grundmann et al., 2007; Zhao et al 2008); however, as both increases and decreases have been reported, the question of how the DA system is affected remains unresolved. The single pan-neuronal model that has been studied with in vivo microdialysis (Balcioglu et al., 2007) shows a deficit in amphetamine-induced striatal DA overflow and abnormality of dopamine transmitter (DAT) function (Hewett et al., 2010). In an effort to dissect out the effect of mutant torsinA on nigrostriatal DA function, we created transgenic mice that selectively express either human wild type or mutant (ΔE) torsinA in the dopaminergic neurons of the midbrain. Here, we report the initial morphologic, neurochemical, and behavioral characterization of these mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenesis and genotyping

Transgenic mice were created using standard methods of pronuclear injection of a linearized construct. The transgene was constructed by amplifying a fragment containing the first mouse protamine intron from the plasmid pLacF and inserting it into the pcDNA3.1hTorsinA plasmid (courtesy of Dr. W.T. Dauer) (Goodchild and Dauer, 2005) between the XbaI and NotI restriction sites. The TorsinA-protamine intron fragment was released with MfeI and SpeI. The GFP cDNA in phTH-IIEGFP (pMAK288-12) (Kessler et al., 2005) was replaced with an SpeI-MfeI oligonucleotide, the resultant plasmid was linearized with MfeI and SpeI, and then ligated to the torsinA cDNA fragment ligated to the protamine intron. The transgene was released from the plasmid with NotI and AflII. Mice were created directly on a C57Bl/6J background at The Rockefeller University. Genotyping was performed as described by Shashidharan et al (2005). Breeding pairs consisted of a transgenic with a non-transgenic C57Bl/6J mouse, so only heterozygote transgenic mice were examined in these studies. Experimental mice were all between 4 and 10 months of age.

Western blotting

For analysis of holoproteins, tissues were harvested in 137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1% v/v NP-40, and 10% v/v glycerol, supplemented with 1 X Mini-Complete protease inhibitors (Invitrogen). Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane following measurement of protein concentrations with the BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), and verified by visualization of total protein by Ponceau Red after transfer to nitrocellulose and/or by demonstration of an equal amount of a marker protein, usually actin. Blots were developed with NEN-DuPont chemiluminescence system (Boston, MA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against torsinA were generously provided by Dr. Pedro Gonzalez-Alegre (Gordon and Gonzalez-Alegre, 2008) and Dr. Brett Lauring (Goodchild et al., 2005) and were used at a dilution of 1:3,000.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemical methods were as previously described (Bogush et al., 2005). Briefly, brains were fixed by transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, followed by overnight immersion fixation in the same fixative and then stored in PBS at 4°C. Brains were sectioned at 40μm using a Leica VT1000 vibratome. Sections were washed serially in PBS and Tris-saline (100 mM Tris, 0.9% NaCl), permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 and 3% goat serum in Tris-saline and then blocked with 3% goat serum in Tris-saline. Primary anti-torsinA antibody (Gordon and Gonzalez-Alegre, 2008) was used at a dilution of 1:3,000 and biotinylated secondary antibody was used at a dilution of 1:500 in Tris-saline with 1% goat serum. The ABC Vectastain kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and the DAB Reagent Set (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) were used to amplify and visualize the immunostaining signal.

Tissue DA content

Tissue contents of striatal DA and DOPAC were determined in freshly dissected striatal samples. The striatum was removed bilaterally, and then bisected. Samples of dorsal striatum (1–4 mg) were taken, weighed, frozen on dry ice, and then stored at −80°C until analysis. On the day of analysis, samples were sonicated in ice-cold, deoxygenated HPLC eluent (10:1 volume to tissue weight), and spun in a microcentrifuge for 2 min at 14,000×g. The supernatant was then injected directly into the HPLC system as described previously (Chen et al., 2001). The mobile phase was 50 mM NaH2PO4, with 3 mg/L sodium octylsulfate, 23.2 mg/L heptanesulfonic acid, 8 mg/L EDTA, and 8–10% methanol, pH 4.5 (modified from Witkovsky et al., 1993); the electrochemical detector was a glassy carbon electrode set at +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Tissue DA and DOPAC content data are given as micromoles per gram tissue wet weight (μmol/g). For HPLC analysis of tissue DA and DOPAC content, DA levels were 100–1000-fold greater than the detection limit and DOPAC was 10-fold greater than detection limits, defined as a signal-to-background ratio of three.

In vivo Microdialysis

Mice were anesthetized with a xylazine/ketamine mixture (4:1) and placed into a modified stereotaxic frame with mouse earbars and nosebar. A custom-constructed microdialysis probe was placed in the dorsal striatum using the following coordinates relative to bregma: +1.5 mm AP, ±1.0 mm ML, and -4.8 mm ventral to the dura. After surgery, the mice were placed in clear polycarbonate cylinders (21.5 cm in height and 17.5 cm in diameter, Instech, Plymouth Meeting, PA), connected to a fluid swivel and allowed to recover overnight. Microdialysis probes were continuously perfused at 1.5 μl/min with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; 147mMNaCl, 1.7mM CaCl2, 0.9mM MgCl2 and 4mM KCl). The following day, mice received an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of cocaine (20mg/kg) or an equivalent volume of saline in a volume of 10 ml/kg after 2 hours of baseline sampling. Sample collection continued for an additional 3 hours after cocaine injection. Dialysate concentrations of DA and serotonin (5-HT), as an index of extracellular concentration, were determined by HPLC coupled to electrochemical detection (HPLC-ED) (Page and Abercrombie, 1999). The detection limit, defined as the sample amount producing a peak height that was twice the height of background noise, was approximately 0.5 pg of 5-HT and 0.3 pg of DA. Mice were euthanized at the end of the experiment by anesthetic overdose. Probe location was marked by a green dye perfused through the probe and brains were collected and frozen for subsequent histological verification of placement in the dorsal striatum. Absolute values of DA and 5-HT in dialysate samples were determined at baseline and were compared among treatment groups by ANOVA. Changes elicited by cocaine are presented as the percentage of baseline. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used to determine differences between treatment groups and changes over time.

Voltammetric monitoring of DA release

Studies of evoked DA release were conducted in acutely prepared brain slices using fast-scan cyclic voltammetry with carbon-fiber microelectrodes. Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg, i.p.) before decapitation. The brain was blocked and coronal slices (350 μm) cut on a Vibratome in ice-cold HEPES-buffered aCSF (Chen and Rice, 2001); slices were held at least 1 h in oxygenated HEPES-aCSF at room temperature before experimentation. Slice recording was performed in a submersion chamber at 32°C, superfused at 1.2 ml/min with bicarbonate-buffered aCSF containing (in mM): NaCl (124); KCl (3.7); NaHCO3 (26); CaCl2 (1.5 or 2.4); MgSO4 (1.3); KH2PO4 (1.3); and glucose (10) saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Striatal DA release was elicited by single-pulse stimulation (100 μs; 0.4–0.8 mA) and monitored at a carbon-fiber microelectrode ~100 μm from a bipolar stimulating electrode; with this paradigm, axonal DA release is Ca2+-dependent and blocked by tetrodotoxin, i.e., exocytotic (Chen and Rice, 2001). Evoked DA release was examined at 3–4 sites per slice, with 3–4 slices per mouse and 3–4 mice per transgenic group. Carbon-fiber microelectrodes were made in-house from 7 μm carbon fibers (Patel et al., 2009). Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry was conducted using a Millar Voltammeter (available by special request to Dr. Julian Millar at St. Bartholomew’s and the Royal London School of Medicine and Dentistry, University of London, UK). Scan range was (−0.7–V) (+1.3 V) vs. Ag/AgCl, scan rate was 800 V/s, and the sampling interval was 100 ms. The monitored substance was identified as DA from the oxidation and reduction peak potentials of its signature voltammogram; evoked extracellular DA concentration ([DA]o) was quantified by post-experiment calibration factors determined in aCSF in the recording chamber at 32°C. Data are given as means +/− SEM (n indicates number of sites) and illustrated as absolute [DA]o or normalized to mean peak [DA]o. Significance of differences was assessed using one-way ANOVA. One-way ANOVA was also used to compare [DA]o clearance (from the 20th to the 60th data point) as an index of possible difference in DA uptake. Significance was considered to be p< 0.05.

Locomotor activity

Locomotor activity was measured as described in Brown et al (2008). The computerized locomotor activity system used was the DigiScan Dmicro (Accuscan Inst., Columbus, OH) and consisted of clear acrylic boxes (45 x 26 x 20 cm) with 16 parallel infrared photobeams. Interruptions of the photobeams were recorded electronically. Total activity was defined as the number of beam breaks that occurred while the animal was ambulating in the chamber. Data were analyzed by two way ANOVA with repeated measures (JMP Statistics) between genotype and over time.

Rotarod

Motor performance was assessed using a Rotamex Rotarod (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) at two, four and six months of age, as described in Brown et al (2008). The first test consisted of three trials per day for four days (12 trials total). A trial involved placing a mouse on a slowly rotating rod that began at 8 rpm and increased 1 rpm every 8 seconds until the mouse fell off the rod or gripped the rod and rotated around with it. Mice received an hour of rest between trials. At subsequent ages, only 3 days of testing were performed (9 total trials). For all testing periods, only the last 6 trials were used, with the initial trials serving as training. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures (SigmaStat, San Jose, CA).

Beam Test

The beam test involved navigation of three wooden beams, each 1 meter long, with varying diameters: narrow, 6.35 mm; medium,12.7 mm; and wide, 25.4 mm (modified from Crabbe et al., 2003). Each beam was elevated 50 cm above the floor. The tester was blind to genotype, and each transgenic line was compared to its own set of controls. The start end of the beam was illuminated and terminated in a dark box. On the first two days of training, the time required for a mouse to traverse the medium beam was recorded during each of 3 consecutive trials, repeated 3 times each day (18 trials). On days 3 and 4, testing began with the wide beam; traversal time and number of hind-limb slips were noted in 2 consecutive trials. This was then repeated with the medium beam and then the narrow beam. A time limit of 30 s was allowed for each trial, and both traversal time and numbers of hind-limb slips were measured. Data were analyzed using t-test for each group on each size beam. Significance was considered to be p< 0.05.

RESULTS

Creation and identification of transgenic lines of mice

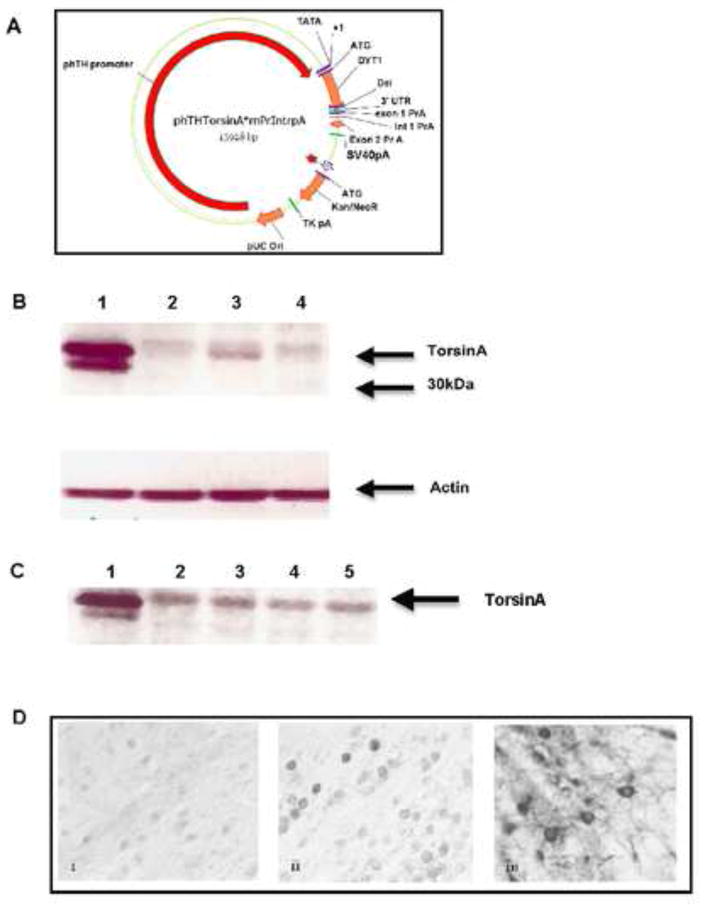

The construct used for transgenesis (Fig. 1A) was derived from the human TH 11Kb promoter fragment (Kessler et al., 2003). Importantly, this promoter directs expression to both the SNpc and the ventral tegmental area (VTA), but does not direct expression to the locus coeruleus. A rabbit polyclonal antibody that recognizes both mouse and human torsinA (Goodchild et al., 2005) was utilized to identify transgene expression by immunoblotting extract from dissected midbrain (Fig. 1B,C), which included the SNpc and VTA. Endogenous torsinA was detected in all regions as was transgenic torsinA in the striatum of Th-hTorsinA mice. Each lane was loaded with 100 μg of protein, and at these levels, the transgene appeared as a doublet. Although standard experimental procedure is to perform initial characterization on at least two transgenic lines derived from any single construct, we obtained only a single line from each construct, i.e. overexpressing either human wild type (TH-hTorsinA) or human mutant torsinA (TH-ΔE-hTorsinA), with sufficient level of transgene expression to warrant further investigation. Importantly, levels of transgene expression were very similar in these two lines. In view of the similarities in phenotype to other models of dystonia that we describe throughout this report, insertional mutations are highly unlikely to account for the abnormalities noted in the characterization of these mice.

FIGURE 1.

Creation of TH-hTorsinA and TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice. The transgenic construct is depicted in (A). DYT1 represents the full-length cDNA for either human wild type or mutant (ΔE) torsinA. (B) Western blot of extracts from a TH-hTorsinA (Lane 1 = midbrain; Lane 2 = neoortex; Lane 3 = striatum; Lane 4 = cerebellum). Blot was also probed for actin, shown in lower panel. (C) Western blot of extracts from a TH-ΔE-hTorsinA male and non-TG male littermate (Lane 1 = TH-ΔE-hTorsinA midbrain; Lane 2 = TH-ΔE-hTorsinA striatum; Lane 3 = non-TG midbrain; Lane 4 = non-TG striatum; Lane 5 = non-TG cerebellum. (D) Brightfield photomicrograph (40X) of the substantia nigra illustrates immunocytochemistry against human-specific torsinA antibody in a non-transgenic (i), TH-ΔE-hTorsinA (ii) or TH-hTorsinA (iii) mouse. Bar = 20 microns.

Human transgene expression was confirmed by immunocytochemisty with an antibody that recognizes only human torsinA (Gordon and Gonzalez-Alegre, 2008) (Fig. 1C). Specific cellular staining outside the midbrain, including in the locus coeruleus, was not detected (data not shown). Both TH-ΔE-hTorsinA and TH-hTorsinA mice exhibited normal fertility and life span. Transmission of the transgene observed the rules of Mendelian genetics.

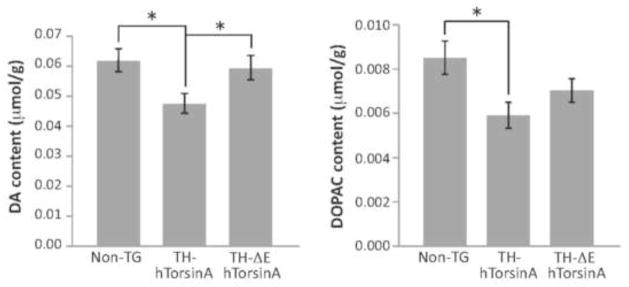

Tissue DA and DOPAC content

Striatal DA and DOPAC contents were determined using HPLC. Striatal DA content in 10–12 week old nontransgenic (non-TG) female mice was 0.061 ± 0.003 μmol/g tissue wet weight (n = 17). DA content in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice did not differ from that in non-TG mice (p > 0.05 vs. non-TG mice, n = 13) (Fig. 2). Striatal DA content in TH-hTorsinA mice was significantly lower than that in non-TG or TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice (n = 12; p < 0.05 vs. non-TG or TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice) (Fig. 2). In the same samples, DOPAC content was significantly lower in TH-hTorsinA mice relative to non-TG mice (p < 0.05 non-TG vs. TH-hTorsinA mice, n = 12–17) (Fig. 2). There was no difference in DOPAC/DA ratio among the three groups (p > 0.05, n = 12–17), suggesting the absence of a detectable change in DA turnover in either transgenic line.

FIGURE 2.

Dopamine and DOPAC content in striatum in TH-ΔE-TorsinA and TH-hTorsinA mice. DA content in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice did not differ from that in non-TG mice (p > 0.05 vs. non-TG mice, n = 13 for each genotype); however, striatal DA content in TH-hTorsinA mice was significantly lower than in non-TG or THΔE-hTorsinA mice (n = 12 for TH-hTorsinA; p < 0.05 vs. non-TG or ΔE-torsinA mice). DOPAC content in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice did not differ from that in non-TG mice (p > 0.05 vs. non-TG mice, n = 13 for each genotype); however, striatal DOPAC content in TH-hTorsinA mice was significantly lower than in non-TG (p < 0.05).

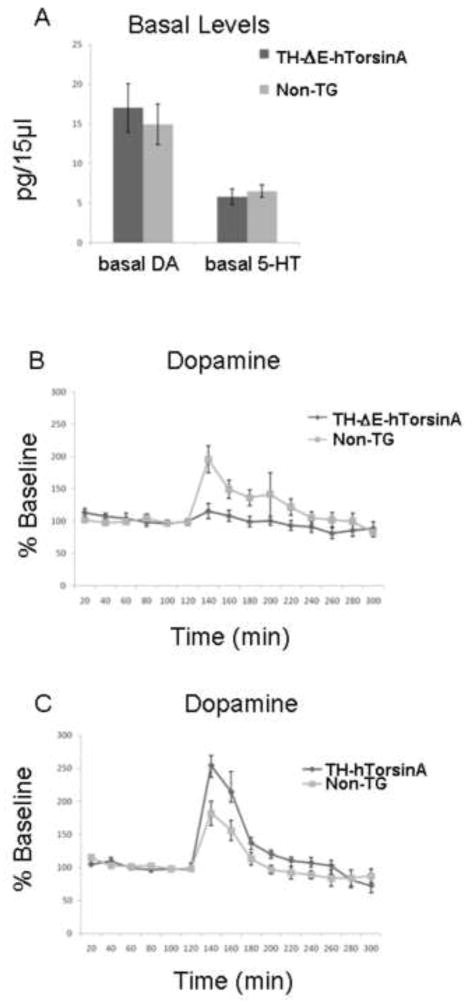

Microdialysis in awake, freely moving animals

We next examined baseline and cocaine amplified [DA]o in the striatum in vivo using microdialysis in awake, freely moving male animals. Concentrations of DA in dialysate did not differ between TH-ΔE-hTorsinA (n = 8) and non-TG male littermates (n = 5) (Fig. 3A). As an additional control, levels of 5-HT were also measured; baseline 5-HT concentration did not differ between TH-ΔE-hTorsinA and non-TG mice (Fig. 3A). Similarly, we found no differences in baseline DA or 5-HT concentrations between TH-hTorsinA (n = 4) and non-TG littermates (n = 7) (data not shown). However, we found that systemic administration of cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.), an inhibitor of the DA transporter (DAT), caused a markedly blunted increase in [DA]o in TH-ΔE- hTorsinA relative to non-TG mice (Fig. 3B). Cocaine elicited a 113 ± 37% increase over baseline in non-TG mice (n = 8) compared to a 23 ± 16% increase in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice (n = 8). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype F[1,14] = 7.22, p < 0.02; a significant effect of time F[7,98] = 7.41, p < 0.0001; and a significant interaction of genotype and time F[7,98] = 2.46, p < 0.03). Importantly, there was no effect of genotype on the elevation of 5-HT overflow between non-TG and TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice (n = 5–8; two-way ANOVA showed no significant effect of genotype, a significant effect of time F[7,70] = 9.84, but no significant interaction of genotype and time, data not shown). In contrast to TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice, cocaine-induced increases in striatal [DA]o in TH-hTorsinA mice (n = 4) were enhanced relative to those in non-TG mice (n = 7) (Fig. 3C). Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype F[1,8] = 7.5, p < 0.03; and time F[7,56] = 4.10, p < 0.001, although no significant interaction F[7,56] = 1.81, p = 0.10). There was also no difference in the effect of cocaine on 5-HT level elevation between TH-hTorsinA and non-TG mice (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Extracellular DA and 5-HT in awake, freely moving animals. (A) Baseline levels of striatal dopamine (DA) are not different between TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice and non-transgenic littermates; ANOVA F[1,14] = 0.27, p = 0.61. Similarly, no baseline difference was observed for serotonin (5-HT; n =8) vs. non-transgenic littermates (n = 5). (B) Striatal DA following intraperitoneal administration of cocaine, 20 mg/kg, shows a marked impairment in striatal DA overflow in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice (n = 8) vs. non-transgenic littermates (n = 8). Two way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype F[1,14] = 7.22, p < 0.02; a significant effect of time F[7,98] = 7.41, p < 0.0001; and a significant interaction of genotype and time F[7,98] = 2.46, p < 0.03. (C) Striatal DA following intraperitoneal administration of cocaine, 20 mg/kg, shows an increase in striatal DA overflow in TH-hTorsinA mice (n = 4) vs. non-transgenic littermates (n = 7). Two way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype F[1,8] = 7.5, p < 0.03; time F[7,56] = 4.10, p < 0.001 but no significant interaction F[7,56] = 1.81, p = 0.10.

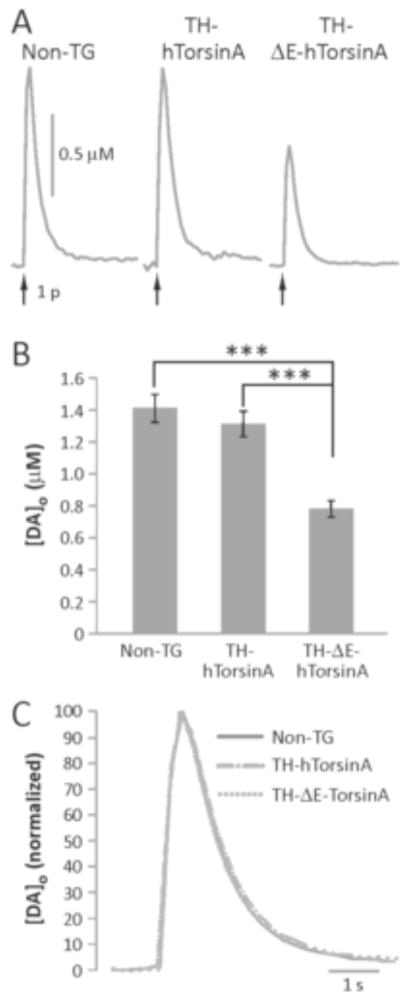

Real-time monitoring of evoked striatal DA release in vitro

Given that cocaine amplifies [DA]o by DAT inhibition, attenuation of cocaine-induced increases in [DA]o in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA vs. non-TG or TH-hTorsinA mice in our microdialysis studies (Fig. 3) implies decreased DA release or altered uptake in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice. To address this with better temporal and spatial resolution than is possible with microdialysis, in which evaluation of extracellular transmitter levels are monitored over sampling times of 2–20 min, we used fast-scan cyclic voltammetry with carbon-fiber microelectrodes (Patel and Rice 2006) to examine DA release and uptake with sub-second resolution in striatal slices from female mice. In initial studies, axonal DA release was evoked by local electrical stimulation, using a single pulse that mimics a single action potential (e.g. Rice and Cragg 2004). Evoked [DA]o was 40% lower in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA than in non-TG or TH-hTorsinA overexpressers (p < 0.001; n = 36–47 sites per group) (Fig. 4A,B), implying decreased DA release or increased DA uptake. To assess whether lower peak [DA]o might be due to increased uptake, we compared [DA]o clearance from averaged, normalized DA release records from each group. Clearance rates were indistinguishable among these groups (p < 0.05 for both comparisons; n = 12–17 sites per group) (Fig. 4C), indicating unaltered DA uptake in these transgenic mice. Given that striatal DA content in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA was equal to or higher than those in non-TG or TH-hTorsinA mice, these data indicate that decreased DA release in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice is not due to low tissue content, but rather that the release process is compromised by overexpression of ΔE-hTorsinA in DAergic neurons. In this same light, data from TH-hTorsinA mice would be consistent with enhanced release in those animals, leading to compensatory changes, including decreased striatal DA content.

FIGURE 4.

Decreased 1 p evoked [DA]o in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice. (A) Representative records of 1 p evoked [DA]o in striatal slices from non-TG mice, and from transgenic mice overexpressing wildtype (TH-hTorsinA) or TH-ΔE-hTorsinA. (B) Mean (± SEM) 1 p evoked [DA]o in striatal slices. Evoked [DA]o was significantly lower in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice than in non-TG control or TH-htorsinA mice (p < 0.001; n = 36–47 sites per group). (C) The time courses of 1 p evoked [DA]o in striatal slices from non-TG, TH-hTorsinA and TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice showed no sign of altered DA clearance (p > 0.05 for all comparisons, n = 5 per group).

Analysis of baseline motor function and cocaine-induced locomotor activity in TH-ΔE- hTorsinA and TH-hTorsinA mice

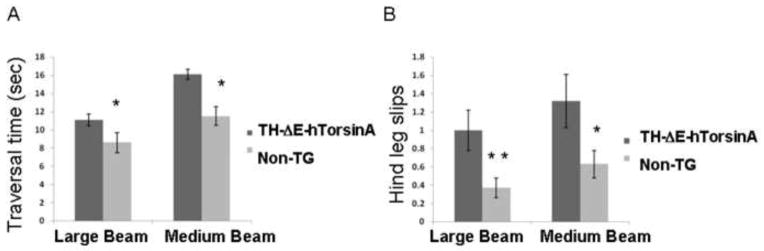

On sustained observation up to two years of age, no abnormal spontaneous movements, including dystonic, were noted in either transgenic genotype. When lifted by their tails, mice did not exhibit clasping, a non-specific abnormality observed in mouse models of central and peripheral motor disease (e.g. Mangiarini et al., 1996; Dupuis et al., 2009). At 2, 4, or 6 months of age, there was no effect of genotype on performance on rotarod in either sex within each transgenic genotype (RM ANOVA p = 0.142; n = 12 female non-TG, 11 male non-TG, 11 female TG-positive, 14 male TG-positive). However, TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice showed deficits in beam walking on both the large and medium beams, in both traversal time and hind leg slips (Figs. 5A,B) (similar testing in TH-hTorsinA mice showed no difference relative to non-TG controls, data not shown). Analysis of males and females (identical cohort as rotarod testing) demonstrated that the difference in traversal time on the medium width beam derived predominantly from the males (males and females combined: hind leg slips: large beam, p = 0.02; medium beam, p = 0.06, and for males only, p = 0.002; traversal time: large beam, p = 0.008, medium beam, p= 0.005). Of note, none of the transgenic or non-transgenic mice were able to satisfactorily traverse the narrow beam in the allotted time.

FIGURE 5.

Deficits in beam walking in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice. Adult male and female mice were tested on 3 beams of progressively smaller size (N = 12 female non-TG, 11 male non-TG, 11 female TH-ΔE-hTorsinA, 14 male TH-ΔE-hTorsinA). Deficits were noted in both traversal time (A) and numbers of hind leg slips (B). Males and females combined: Traversal time: large beam, p = 0.008, medium beam, p= 0.005, narrow beam, p = 0.68; Hind leg slips: large beam, p = 0.02; medium beam, p = 0.06, and for males only, p = 0.002; narrow beam, p = 0.45). None of the transgenic or non-TG mice was able to satisfactorily traverse the narrow beam in the allotted time, so the data is not shown. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.05.

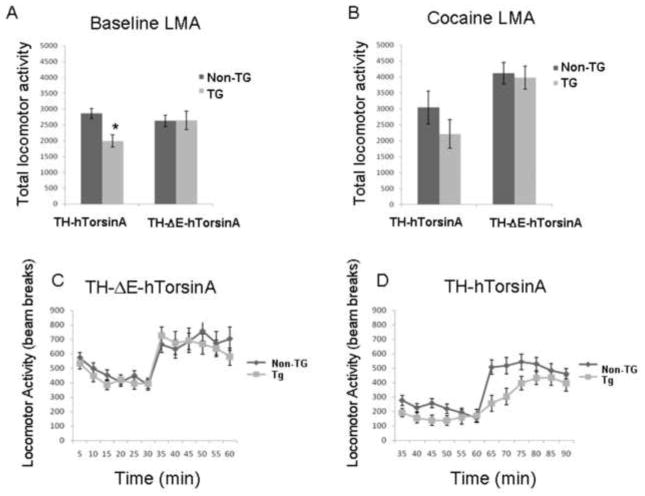

Total locomotor activity was measured in adult male mice (4–10 months) at baseline, and following saline and/or cocaine (20 mg/kg ip) injection. Baseline locomotor activity was lower in TH-hTorsinA than in non-TG mice (one-way ANOVA ; F[1,19] = 11.8, p< 0.003, Fig. 6A), similar to what was noted in prp (prion promoter) hTorsinA transgenic mice (Grundmann et al., 2007). Following an injection of saline, locomotor activity in TH-hTorsinA mice was not different from non-transgenic controls (one-way ANOVA; F[1,19] = 0.91; p = 0.35). After 30 minutes, the same mice received an injection of cocaine (20mg/kg, i.p, Fig. 6C). Several transgenic mice (4/11) had an acute, cataleptic-like response and remained immobilized for several minutes but then resumed activity. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures showed a significant effect of time (F[6,114] = 9.04, p < 0.0001) but no significant effect of genotype (F[1,19] = 0.39, p = 0.54) and no significant interaction F[6,114] = 1.42, p = 0.21). Baseline activity in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice did not differ from their non-TG littermates (one-way ANOVA F[1,30] = 0.03; p = 0.87, and also was not different from non-TG mice which received an injection of saline (one-way ANOVA; F[1,30] = 0.04, p = 0.84, data not shown). A separate group of mice received an injection of cocaine (20 mg/kg ip) 30 minutes after being placed in the locomotor activity boxes. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures showed a significant effect of time (F[6,156] = 12.6; p < 0.0001) but no significant effect of genotype (F[1,26] = 0.06, p = 0.80) and no significant interaction (F[6,156] = 1.20, p = 0.30, ANOVA, Fig. 6D). There was no cataleptic-like response in non-TG or TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice.

FIGURE 6.

Locomotor activity (LMA) in TH-hTorsinA and TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice. (A) Baseline locomotor activity was lower in TH-hTorsinA than in non-transgenic mice (One way ANOVA; F[1,19] = 11.8, p< 0.003) and was unchanged in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice (One way ANOVA F[1,30] = 0.03; p = 0.87). (B) Total locomotor activity in TH-hTorsinA and TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice was not different from non-Tg controls following an injection of cocaine; time courses are indicated in (C) and (D). (C) TH-ΔE-hTorsinA received an injection of cocaine at arrow (20 mg/kg, i.p.). Two way ANOVA with repeated measures showed a significant effect of time (F[6,114] = 9.04, p < .0001) but no significant effect of genotype (F[1,19] = 0.39, p = 0.54) and no significant interaction F[6,114] = 1.42, p = 0.21). (D) TH-hTorsinA mice received an injection of cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.). Two way ANOVA with repeated measures showed a significant effect of time (F[6,156] = 12.6; p < .0001) but no significant effect of genotype (F[1,26] = .06, p = 0.80) and no significant interaction (F[6,156] = 1.20, p = 0.30)

DISCUSSION

The pathophysiology underlying dystonia remains unknown. Various, potentially overlapping, lines of evidence point to a loss of inhibitory transmission at several levels of the central nervous system, abnormality of sensorimotor learning and integration, and abnormal, or maladaptive, plasticity during the learning of new motor skills, which may be influenced by environmental and/or developmental factors (reviewed in Quartarone et al., 2008). Each of these deficits could involve dopamine. The interplay between learning, maladaptive plastic changes, including altered postsynaptic plasticity, and environmental factors is particularly attractive in explaining EOTD, a dominantly inherited disorder with reduced penetrance and symptomatic onset during childhood. The source, i.e. synaptic origin, of these maladaptive changes is also unknown, as existing evidence points to cortex, cerebellum, basal ganglia, and all their connections, e.g. thalamus, with plastic modifications potentially obscuring primary abnormalities. This study represents a first attempt to identify primary areas of pathophysiology in dystonia by neuronal subtype-specific expression of human wild type and mutant torsinA.

Using mice engineered to express hTorsinA or ΔE-hTorsinA in the dopaminergic neurons of the midbrain that project to striatum, we show that this cell-specific expression is sufficient to account for previously reported motor phenotypes and DA dysfunction in transgenic mice engineered to express hTorsinA or ΔE-hTorsin in a pan-neuronal pattern. As in these other transgenic “models” of torsinA dystonia (Sharma et al. 2005; Dang et al, 2005,2006; Grundmann et al, 2007), the mice described herein do not have obvious gross motor dysfunction, including dystonia. However, TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice display deficits in beam walking. Similar to the prp-directed model of hTorsinA transgene expression (Grundmann et al., 2007), TH-hTorsinA mice also show baseline hypoactivity. Implicating DA dysfunction. Balcioglu and colleagues (2007) found a roughly 50% decrease in amphetamine-induced striatal DA overflow in mice with pan-neuronal expression of ΔE-hTorsinA compared to non-TG controls. Consistent with these data, we found that cocaine, a monoamine transporter inhibitor that does not cause DA release, also produced a blunted increase in striatal [DA]o in vivo in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA versus non-TG mice.

Given that cocaine is a DAT inhibitor, blunted [DA]o elevation implies either compromised DAT activity or altered DA release in ΔE-hTorsinA mice. As standard microdialysis measurement cannot readily distinguish between effects on DA release versus DA uptake, we used real-time voltammetric recording of evoked [DA]o in striatal slices to address the effects of ΔE-hTorsinA on peak evoked [DA]o and DA clearance. Those experiments revealed that peak evoked [DA]o was also blunted in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice compared to non-TG or TH-hTorsinA mice, despite similar tissue levels of DA in TH-ΔE-TorsinA compared to non-TG mice, with no difference in DA clearance after release in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice compared to non-TG or TH-hTorsinA ice. These data indicate a cell-autonomous effect on DA release, rather than uptake, thus arguing against a major role for a previously reported interaction between ΔE-TorsinA and the DAT (Torees et al., 2004). The data are consistent, however, with previous work showing evidence of ΔE-hTorsinA interactions with the vesicle fusion protein, snapin (Granata et al., 2008). Hewett et al (2010) recently reported an abnormality in DAT function in a pan-cellular mouse DYT1 model. Additionally, abnormalities of DA turnover, as suggested by an increased DOPAC/DA ratio, have been found in DYT1 human brain (Augood et al., 2002) and in a pan-neuronal mouse model (Zhou et al., 2008). It appears, therefore, that DAT malfunction and abnormalities of DA turnover in DYT1 may arise from cell-cell interactions rather than from a direct effect of ΔE-hTorsinA.

Thus, both in vivo and in vitro data indicate that impaired DA release is a consequence of ΔE-hTorsinA overexpression. Strikingly, despite low [DA]o elevation, cocaine-induced increases in locomotor activity were indistinguishable between TH-ΔE-hTorsinA and non-TG mice. These data suggest compensatory changes in DA signaling that maintain nigrostriatal DA system function. Indeed, despite markedly attenuated DA overflow in response to cocaine, TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mice display an equivalent degree of hyperlocomotion relative to non-transgenic littermates. The level of DA overflow does not always correlate with the degree of hyperlocomotion, as in the comparison between cocaine and amphetamine (Kuczenski et al., 1991); however, the very limited elevation of [DA]o seen in TH-ΔE-hTorsinA versus non-TG mice given the same dose of cocaine, strongly suggests non-cell-autonomous upregulation of postsynaptic DA neurotransmission in the striatum, presumably in dopaminoceptive medium spiny output neurons (e.g. Pettit et al., 1990; Szumlinski et al., 2009). Indeed, abnormalities of dopamine D2 receptors have been identified in DYT1 patients (Carbon et al., 2009) and mice (Napolitano et al., 2010)

Lastly, the increased DA overflow seen with cocaine in TH-hTorsinA compared to non-TG mice further provides the first evidence that a normal role of torsinA is to facilitate DA release. Interestingly, peak evoked [DA]o in TH-hTorsinA did not differ from that in non-TG mice, despite significantly lower striatal DA content. These findings may also reflect changes in DA signaling; in this case, facilitated DA release in TH-hTorsinA mice would be expected to lead to a decrease in the sensitivity of DA receptors, including DA autoreceptors. This could lead to compensatory decreases DA in DA synthesis and lower DA content. The hypothesis of decreased DA signaling in TH-hTorsinA mice is substantiated by the trend towards a decreased locomotor response to cocaine in the TH-hTorsinA, which implies decreased post-synaptic efficacy.

Post-synaptic DA receptor supersensitivity as a form of nigrostriatal plasticity occurs as an adaptation to a deficit in DA transmission accompanied by pulsatile DA stimulation (reviewed in Calabresi et al., 2008). It is characterized by an enhanced locomotor response to DA, and can be associated with an increased number and/or sensitivity of receptors, the latter due to alterations in signal transduction. Such an enhanced response is best recognized in Parkinson’s disease, and may underlie levodopa-induced dyskinesia (LID) (e.g. Gerfen, 2003; Westin et al., 2007; Calabresi et al., 2008). In animal models of PD, DA receptor supersensitivity develops when DA release is almost entirely abolished and animals are primed with L-DOPA, leading to dyskinesias, similar to clinical LID. A similar form of supersensitivity exists in genetically DA-deficient mice (Kim et al., 2000), but relevant to our study, it also exists in mutant mice with normal baseline extracellular DA levels, including GRK6- and dopamine-β-hydroxylase-deficient mice (Gainetdinov et al., 2003; Schank et al., 2006). Thus, although not the molecular equivalent of PD-like supersensitivity, we hypothesize that expression of ΔE-torsinA leads to abnormalities of DA release and a novel form of exaggerated DA signaling, possibly reflecting post-synaptic DA receptor supersensitivity or imbalance, which could contribute to a dyskinetic phenotype. Consistent with this hypothesis, D2 agonist activation of striatal cholinergic interneurons is enhanced in a pan-neuronal mouse model of EOTD (Pisani et al., 2006, 2007). Moreover, striatal D2 receptor binding is decreased in non-manifesting DYT1 carriers (Asanuma et al., 2005; Carbon et al., 2009). Dopamine receptor supersensitivity may also contribute to the worsening of symptoms in many DYT1 patients treated with L-DOPA (Bressman, 2003), and has been implicated in the genetic rodent model of paroxysmal dystonia (Rehders et al., 2000). Further work is required to identify downstream signal transduction pathways that may contribute to altered DA sensitivity in the TH-ΔE-hTorsinA mouse.

The findings presented here demonstrate that ΔE-hTorsinA causes cell-autonomous abnormalities in DA neurotransmission, thereby supporting the notion of DA dysregulation in EOTD. A change in DA release, but not uptake, appears to be the primary consequence of both TH-ΔE-hTorsinA and TH-hTorsinA expression. These data not only provide new insight into the consequences of DYT1 mutation, but also indicate a role for torsinA in the regulation of transmitter release. Demonstration of impaired DA release complements previous findings form PC12 cells showing that knockdown of torsinA compromised the exo-endocytotic process to a similar extent as knockdown of the vesicle-associated protein snapin, with overexpression of ΔE-hTorsinA leading to a similar loss of function (Granata et al., 2008). The present studies provide the first evidence that ΔE-hTorsinA also leads to compromised cell-autonomous transmitter release in the CNS. In addition to DA, dysfunction of several other transmitter systems has been implicated in dystonia, including glutamate, GABA and acetylcholine (reviewed in Pisani et al., 2007). Compromised release and function of those transmitters would potentially exacerbate the consequences of DA disruption through a deleterious imbalance in the neurotransmitters regulating movement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH 1R21NS047432 (to M.E.E.) and NIH 1R01NS36362 and 1R01NS45325 (to M.E.R.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Asanuma K, Ma Y, Okulski J, Dhawan V, Chaly T, Carbon M, Bressman SB, Eidelberg D. Decreased striatal D2 receptor binding in non-manifesting carriers of the DYT1 dystonia mutation. Neurology. 2005;64:347–349. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149764.34953.BF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augood SJ, Keller-McGandy CE, Siriani A, Hewett J, Ramesh V, Sapp E, DiFiglia M, Breakefield XO, Standaert DG. Distribution and ultrastructural localization of torsinA immunoreactivity in the human brain. Brain Res. 2003;986:12–21. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcioglu A, Kim MO, Sharma N, Cha JH, Breakefield XO, Standaert DG. Dopamine release is impaired in a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. J Neurochem. 2007;102:783–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakefield XO, Kamm C, Hanson PI. TorsinA: movement at many levels. Neuron. 2001;31:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breakefield XO, Blood AJ, Li Y, Hallett M, Hanson PI, Standaert DG. The pathophysiological basis of dystonias. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:222–234. doi: 10.1038/nrn2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressman SB. Dystonia: phenotypes and genotypes. Rev Neurol. 2003;159:849–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TB, Bogush AI, Ehrlich ME. Neocortical expression of mutant huntingtin is not required for alterations in striatal gene expression or motor dysfunction in a transgenic mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3095–3104. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Di Filippo M, Ghiglieri V, Picconi B. Molecular mechanisms underlying levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Mov Disord. 2008;23(Suppl 3):S570–S579. doi: 10.1002/mds.22019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Gelwix CC, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA. Torsin-mediated protection from cellular stress in the dopaminergic neurons of Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3801–3812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5157-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon M, Niethammer M, Peng S, Raymond D, Dhawan V, Chaly T, Ma Y, Bressman S, Eidelberg D. Abnormal striatal and thalamic dopamine neurotransmission: Genotype-related features of dystonia. Neurology. 2009;72:2097–103. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181aa538f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BT, Rice ME. Novel Ca2+ dependence and time course of somatodendritic dopamine release: substantia nigra versus striatum. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7841–7847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07841.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BT, Avshalumov MV, Rice ME. H(2)O(2) is a nove, endogenous modulator of synaptic dopamine release. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2468–2476. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.6.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Metten P, Yu CH, Schlumbohm JP, Cameron AJ, Wahlsten D. Genotypic differences in ethanol sensitivity in two tests of motor incoordination. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1338–1351. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00132.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, McNaught KS, Jengelly TA, Jackson T, Li J, Li Y. Generation and characterization of Dyt1 DeltaGAG knock-in mouse as a model for early-onset dystonia. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:452–463. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang MT, Yokoi F, Pence MA, Li Y. Motor deficits and hyperactivity in Dyt1 knockdown mice. Neurosci Res. 2006;56:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis L, Fergani A, Braunstein KE, Eschbach J, Holl N, Rene F, Gonzalez De Aguilar JL, Zoerner B, Schwalenstocker B, Ludolph AC, Loeffler JP. Mice with a mutation in the dynein heavy chain 1 gene display sensory neuropathy but lack motor neuron disease. Exp Neurol. 2009;215:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov RR, Bohn LM, Sotnikova TD, Cyr M, Laakso A, Macrae AD, Torres GE, Kim KM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG, Premont RT. Dopaminergic supersensitivity in G protein-coupled receptor kinase 6-deficient mice. Neuron. 2003;38:291–303. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR. D1 dopamine receptor supersensitivity in the dopamine-depleted striatum animal model of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscientist. 2003;9:455–462. doi: 10.1177/1073858403255839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild RE, Kim CE, Dauer WT. Loss of the dystonia-associated protein torsinA selectively disrupts the neuronal nuclear envelope. Neuron. 2005;48:923–932. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KL, Gonzalez-Alegre P. Consequences of the DYT1 mutation on torsinA oligomerization and degradation. Neuroscience. 2008;157:588–595. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata A, Watson R, Collinson LM, Schiavo G, Warner TT. The dystonia-associated protein torsinA modulates synaptic vesicle recycling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7568–7579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granata A, Schiavo G, Warner TT. TorsinA and dystonia: from nuclear envelope to synapse. J Neurochem. 2009;109:1596–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann K, Reischmann B, Vanhoutte G, Hübener J, Teismann P, Hauser TK, Bonin M, Wilbertz J, Horn S, Nguyen HP, Kuhn M, Chanarat S, Wolburg H, Van der Linden A, Riess O. Overexpression of human wildtype torsinA and human DeltaGAG torsinA in a transgenic mouse model causes phenotypic abnormalities. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;27:190–206. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett JW, Zeng J, Niland BP, Bragg DC, Breakefield XO. Dystonia-causing mutant torsinA inhibits cell adhesion and neurite extension through interference with cytoskeletal dynamics. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:98–111. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett J, Johanson P, Sharma N, Standaert D, Balcioglu A. Function of dopamine transporter is compromised in DYT1 transgenic animal model in vivo. J Neurochem. 2010 Feb 2; doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06590.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm C, Boston H, Hewett J, Wilbur J, Corey DP, Hanson PI, Ramesh V, Breakefield XO. The early onset dystonia protein torsinA interacts with kinesin light chain 1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19882–19892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler MA, Yang M, Gollomp KL, Jin H, Iacovitti L. The human tyrosine hydroxylase gene promoter. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;112:8–23. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DS, Szczypka MS, Palmiter RD. Dopamine-deficient mice are hypersensitive to dopamine receptor agonists. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4405–4413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04405.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konakova M, Pulst SM. Immunocytochemical characterization of torsin proteins in mouse brain. Brain Res. 2001;922:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS, Aizenstein ML. Amphetamine, cocaine, and fencamfamine: relationship between locomotor and stereotypy response profiles and caudate and accumbens dopamine dynamics. J Neurosci. 1991;11:2703–2712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-09-02703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiarini L, Sathasivam K, Seller M, Cozens B, Harper A, Hetherington C, Lawton M, Trottier Y, Lehrach H, Davies SW, Bates GP. Exon 1 of the HD gene with an expanded CAG repeat is sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. Cell. 1996;87:493–506. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraro NI, Moffat KG. Down-regulation of torp4a, encoding the Drosophila homologue of torsinA, results in increased neuronal degeneration. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:1338–1353. doi: 10.1002/neu.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano F, Pasqualetti M, Usiello A, Santini E, Pacini G, Sciamanna G, Errico F, Tassone A, Di Dato V, Martella G, Cuomo D, Fisone G, Bernardi G, Mandolesi G, Mercuri NB, Standaert DG, Pisani A. Dopamine D2 receptor dysfunction is rescued by adenosine A2A receptor antagonism in a model of DYT1 dystonia. Neurobiol Dis. 2010 Mar 19; doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.003. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nery FC, Zeng J, Niland BP, Hewett J, Farley J, Irimia D, Li Y, Wiche G, Sonnenberg A, Breakefield XO. TorsinA binds the KASH domain of nesprins and participates in linkage between nuclear envelope and cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3476–3486. doi: 10.1242/jcs.029454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozelius LJ, Hewett J, Page C, Bressman S, Kramer P, Shalish C, de Leon D, Brin M, Raymond D, Corey DP, Fahn S, Risch N, Buckler A, Gusella JF, Breakefield XO. The early-onset torsion dystonia gene (DYT1) encodes an ATP-binding protein. Nat Genet. 1997;17:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page ME, Abercrombie ED. Discrete local application of corticotropin-releasing factor increases locus coeruleus discharge and extracellular norepinephrine in rat hippocampus. Synapse. 1999;33:304–313. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990915)33:4<304::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel JC, Rice ME. Dopamine Release in Brain Slices. In: Grimes CA, Dickey EC, Pishko MV, editors. Encyclopedia of Sensors. American Scientific Publishers; Stevenson Ranch, California: 2006. pp. 313–334. [Google Scholar]

- Patel JC, Witkovsky P, Avshalumov MV, Rice ME. Mobilization of intracellular calcium stores facilitates somatodendritic dopamine release. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6568–6579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0181-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picconi B, Pisani A, Barone I, Bonsi P, Centonze D, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Pathological synaptic plasticity in the striatum: implications for Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology. 2005;267:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Martella G, Tscherter A, Bonsi P, Sharma N, Bernardi G, Standaert DG. Altered responses to dopaminergic D2 receptor activation and N-type calcium currents in striatal cholinergic interneurons in a mouse model of DYT1 dystonia. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:318–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani A, Bernardi G, Ding J, Surmeier DJ. Re-emergence of striatal cholinergic interneurons in movement disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quartarone A, Rizzo V, Morgante F. Clinical features of dystonia: a pathophysiological revisitation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:484–490. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328307bf07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehders JH, Löscher W, Richter A. Evidence for striatal dopaminergic overactivity in paroxysmal dystonia indicated by microinjections in a genetic rodent model. Neuroscience. 2000;97:267–277. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Cragg SJ. Nicotine amplifies reward-related dopamine signals in striatum. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:583–584. doi: 10.1038/nn1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schank JR, Ventura R, Puglisi-Allegra S, Alcaro A, Cole CD, Liles LC, Seeman P, Weinshenker D. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase knockout mice have alterations in dopamine signaling and are hypersensitive to cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2221–2230. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Hewett J, Ozelius LJ, Ramesh V, McLean PJ, Breakefield XO, Hyman BT. A close association of torsinA and alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies: a fluorescence resonance energy transfer study. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:339–344. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61700-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Baxter MG, Petravicz J, Bragg DC, Schienda A, Standaert DG, Breakefield XO. Impaired motor learning in mice expressing torsinA with the DYT1 dystonia mutation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5351–5355. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0855-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashidharan P, Good PF, Hsu A, Perl DP, Brin MF, Olanow CW. TorsinA accumulation in Lewy bodies in sporadic Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. 2000;877:379–381. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashidharan P, Kramer BC, Walker RH, Olanow CW, Brin MF. Immunohistochemical localization and distribution of torsinA in normal human and rat brain. Brain Res. 2000;853:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashidharan P, Sandu D, Potla U, Armata IA, Walker RH, McNaught KS, Weisz D, Sreenath T, Brin MF, Olanow CW. Transgenic mouse model of early-onset DYT1 dystonia. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:125–133. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Sweeney AL, Beaulieu JM, Shashidharan P, Caron MG. Effect of torsinA on membrane proteins reveals a loss of function and a dominant-negative phenotype of the dystonia-associated DeltaE-torsinA mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15650–15655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308088101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westin JE, Vercammen L, Strome EM, Konradi C, Cenci MA. Spatiotemporal pattern of striatal ERK1/2 phosphorylation in a rat model of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia and the role of dopamine D1 receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:800–810. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann T. Commentary: Dopaminergic dysfunction in DYT1 dystonia. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky P, Nicholson C, Rice ME, Bohmaker K, Meller E. Extracellular dopamine concentration in the retina of the clawed frog, Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5667–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, DeCuypere M, LeDoux MS. Abnormal motor function and dopamine neurotransmission in DYT1 DeltaGAG transgenic mice. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]