Abstract

The purpose of this review is to have an overview on the applications on the autologous fibrin glue as a bone graft substitute in maxillofacial injuries and defects. A search was conducted using the databases such as Medline or PubMed and Google Scholar for articles from 1985 to 2016. The criteria were “Autograft,” “Fibrin tissue adhesive,” “Tissue engineering,” “Maxillofacial injury,” and “Regenerative medicine.” Bone tissue engineering is a new promising approach for bone defect reconstruction. In this technique, cells are combined with three-dimensional scaffolds to provide a tissue-like structure to replace lost parts of the tissue. Fibrin as a natural scaffold, because of its biocompatibility and biodegradability, and the initial stability of the grafted stem cells is introduced as an excellent scaffold for tissue engineering. It promotes cell migration, proliferation, and matrix making through acceleration in angiogenesis. Growth factors in fibrin glue can stimulate and promote tissue repair. Autologous fibrin scaffolds are excellent candidates for tissue engineering so that they can be produced faster, cheaper, and in larger quantities. In addition, they are easy to use and the probability of viral or prion transmission may be decreased. Therefore, autologous fibrin glue appears to be promising scaffold in regenerative maxillofacial surgery.

Key Words: Autograft, fibrin tissue adhesive, maxillofacial injury, tissue engineering

INTRODUCTION

Reconstruction of maxillofacial bone defects resulting from trauma, cancer, congenital malformation, or infection is one of the most important goals for oral and maxillofacial surgeons and orthopedists.[1,2] An ideal bone graft material must have osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive characteristics which are three important elements of new bone formation.[3] New bone formation by osteoprogenitor cells or osteoblastic cells existing in the graft material is regarded as osteogenesis.[4,5] Osteoinduction is introduced as the capability to cause pleuripotent cells, from a nonosseous environment to differentiate into chondrocytes and osteoblasts, resulting into bone formation.[6] Osteoconduction refers to providing a suitable environment such as development of capillaries and cells from the host into a three-dimensional structure to bone ingrowth.[6,7]

Autologous bone graft has osteoconductive, osteogenic, and osteoinductive properties and consists of a bone matrix, autologous cells, and growth factors which are present in the matrix.[8,9] Among bone transplants supporting bone regeneration, autologous bone graft (rib, iliac crest, tibia) has been the gold standard to restore bone defects which naturally provides all the necessary elements for bone regeneration.[10,11,12] However, a need to provide another surgical procedure, irregular rates of resorption,[13] its restricted available amounts, displacement of bone graft particles during their placement,[14] donor site morbidity and deformity,[2,15] increase of infection risk, and cost and time of the treatment[16,17] are drawbacks of this method. In addition, it may show poor viability because of the lack of vascularization.[18]

Recently, bone tissue engineering with avoidance of harvesting autologous bone graft is a promising approach for bony defect reconstruction.[12,19] In this technique, cells are combined with three-dimensional scaffolds to provide a tissue-like structure to replace lost parts of the tissues and organs.[20,21] The primary goal of bone tissue engineering is selecting the most appropriate scaffolds.[12,22,23] The scaffold should be biocompatible, biodegradable, and should also allow reasonable cell adhesion interactions.[24,25] In addition, it must increase bone ingrowth through osteoinduction, should not impose any adverse effects on the surrounding tissues due to proceeding, must be malleable or flexible and adaptable to irregular bone defect sites, and should be easy to use.[6]

Synthetic biodegradable polymers such as polyglycolic acids, polylactic acid, and poly lactic-co- glycolic acid are commonly used in bone tissue engineering. However, after their implantation in an in vivo model, a great release of acid products occurs which can result in an inflammatory response.[26]

Natural polymers such as chitosan, collagen, and glycosaminoglycans are scaffolds which have been used in bone tissue engineering.[27] Fibrin as a natural scaffold, because of its biocompatibility and biodegradability, and the initial stability of the grafted stem cells, has been introduced an excellent scaffold for bone tissue engineering.[24] It may act as a scaffold to provide cell migration into the repairing site and release growth factors over an extended period.[28]

The aim of this review is to introduce autologous fibrin glue and describe its roles and applications in regenerative maxillofacial surgery that could be proposed as bone graft substitute.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In the present review, a search was conducted using the databases such as Medline or PubMed and Google Scholar for articles from 1985 to 2016. The Medical Subject Heading terms or criteria were as follows: “Autograft,” “Fibrin tissue adhesive,” “Tissue engineering,” “Maxillofacial injury,” and “Regenerative medicine.” All articles were selected, with no inclusion or exclusion criteria.

FIBRIN GLUE STRUCTURE

Fibrin glue, also named fibrin sealant or fibrin tissue adhesive, consists of enriched fibrinogen, also known as cryoprecipitate, thrombin, fibronectin,[29] factor XIII (F XIII), anti-fibrinolytic agents (such as aprotinin and tranexamic acid),[24] calcium chloride,[30] and platelet growth factors.[31] Fibrinogen with a molecular weight of 340 kD is an abundant plasma protein and constructed in the liver.[32] Thrombin is an endoprotease that acts as a blood clotting factor to turn fibrinogen into fibrin.[32] Furthermore, it activates fibrin-stabilizing factor XIII which permits for firm fibrin cross-linkage (in the presence of ionized calcium) and the formation of a constant and nonfragile clot. Fibronectin, similar to thrombin, also participates in fibrin cross-linkage that results in increased cellular migration and fibroblastic development in sites where fibrin glue is used.[29] Factor XIII in fibrin glue helps in the emigration of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells on the highly cross-linked structure of the glue and it raises the proliferation of these cells.[6] After mixing of fibrinogen and thrombin together, within a few seconds, a gel-like component is formed.[32]

ROLES OF FIBRIN GLUE

Mixing of fibrinogen and thrombin results in the final stage of coagulation cascade that fibrinogen is converted into fibrin monomers and finally forming a three-dimensional network.[33]

For more than 100 years, fibrin has been introduced as a blood clotting agent and has been applied in human medicine since 1960s. For the first time, it was sold in the late 1970s, to promote hemostasis and to end bleeding when traditional methods could not control bleeding.[34] At present, it can be used as a hemostatic agent in different surgeries to reduce blood loss or postoperative bleeding[9] and also in hemophilia patient surgeries.[35]

The role of fibrin glue or fibrin adhesive in surgery has been recognized since 1972 when Matras et al.[36] used it as an autologous cryoprecipitate solution mixed with an identical amount of thrombin to repair a digital nerve.[14] In addition, because of chemical and mechanical properties of fibrin,[26] it has been used as a sealant system, for example, in colonic and intestinal anastomosis to accelerate fistula closure and laparoscopic/endoscopic procedures.[35] Not only it has been applied as hemostatic agent and sealant material, but also it has served to improve the healing of severe burns, chronic wounds,[27] protection against bacterial infection,[37] and also as a drug delivery system.[38] It has been explained that this glue has good acceptability, and cases of incompatible events have rarely been reported.[39,40]

Fibrin, as a natural biomaterial, has structure similar to the native extracellular matrix and has proven biocompatibility, biodegradation, and binding capacity to cells.[24,41] The start-up of biodegradation of fibrin glue occurs in about 24 h,[14] its half-life is about 4.6 days, and some studies show that it completely disappears from the body within 30 days. However, one study claimed that complete resorption takes place by the 3rd day, and another study asserted that lysis of commercially produced fibrin glue occurs within 1–2 weeks.[42,43] Using fibrin glue scaffold prevents foreign body reaction in the injured site.[14]

The scaffold which is used in tissue engineering must be suitable for cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation.[44] Fibrin is believed to have a critical role in cellular and matrix interaction. It promotes cell migration, proliferation, and allows making of matrix through acceleration in angiogenesis.[45] Growth factors in fibrin glue such as transforming growth factor-beta, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and epidermal growth factor can stimulate and promote tissue repair.[24,46] Before complete resorption of fibrin scaffold at the injured site, the cells multiply and differentiate into new tissues.[45] It acts as a carrier of growth factors to stimulate angiogenesis, maintains growth factors at the wound site, and prevents soft tissue prolapse.[47]

Regeneration of adipose tissue, cardiac tissue, cartilage, cornea, skin, bone, liver, nervous tissue, tendon, and ligament are several of the applications of fibrin alone or in combination with other materials as a biological scaffold in tissue engineering.[24,27]

AUTOLOGOUS FIBRIN GLUE

There are commercial fibrins prepared from pooled blood (blood from several donors)[48] which can be used as a scaffold in tissue engineering, but on the one hand, they are expensive, and on the other hand, bring a weak cell survival that makes their usage complex as three-dimensional scaffolds for cell culture.[24]

Compared to commercial fibrins, autologous fibrin scaffolds which are prepared from a single donor[48] are excellent candidates for tissue engineering, because they can be produced in faster, cheaper,[24] and larger quantities.[34,46] In addition, they are easy to use, have a better tolerance,[34] and the probability of viral transmission or prion infection may be decreased.[34]

Since the recipient is his/her own blood donor, probable risk of infection or of foreign body reaction might be reduce by using autologous fibrin glue, unlike xenogenic gelatin and collagen that may cause inflammatory responses.[24] Furthermore, this type of fibrin scaffold is described as an appropriate matrix for cell growth and differentiation[49,50,51] and as release systems of growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor[52,53] and bFGF.[54] Finally, these features introduce autologous fibrin glue as an interesting scaffold in tissue engineering.

ROLE OF FIBRIN GLUE IN ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY

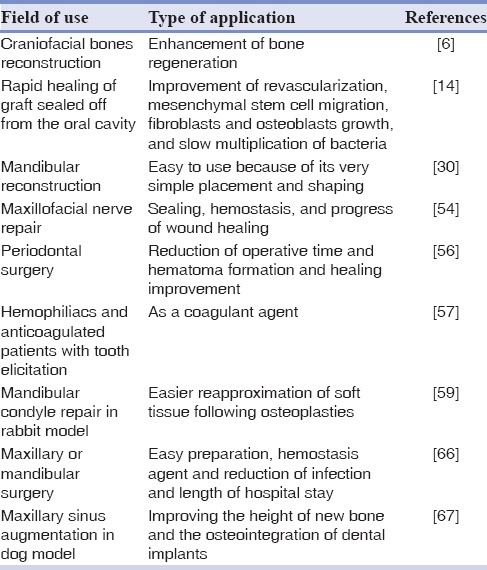

The historical overview of role of fibrin glue in oral and maxillofacial surgery is shown in Table 1. The application of fibrin glue was first described in the field of oral and maxillofacial surgery by Matras in 1982.[55] This researcher explained fibrin glue as a substance owing to the features of tissue sealing, hemostasis, and progress of wound healing in which its usage in maxillofacial nerve repair has a good outcome following traumatic and tumor injuries. Then, this researcher reported the usage of fibrin glue as a hemostatic agent in soft tissue injuries and also as a substitute for suture material in skin graft method and in the drawing of bone fragments in complicated fractures.[29] In addition, fibrin glue, a composite of fibrinogen and thrombin, was described by Keller et al., 1985, as a suitable scaffold for bone regeneration because of its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and capacity of cell binding.[57]

Table 1.

Historical overview of role of fibrin glue in oral and maxillofacial surgery

Pini Prato et al. in 1987 compared the use of a commercial sealant system with common suture repair for flap and graft placement in periodontal surgery.[58] Fibrin adhesive led to reduced operative time and hematoma formation and improved healing. Also, Baudo et al. in 1988 showed a decreased need for postoperative factor therapy in hemophiliacs and anticoagulated patients who were undergoing tooth elicitation.[59] Bosch et al.[60] demonstrated that fibrin glue, by significantly reducing the size of the gaps between bony fragments and accelerating the revascularization, improved bone graft incorporation and remodeling. In addition, on comparison, multiplication of microorganisms in the fibrin clot is significantly slower than blood coagulum. These findings could describe the uneventful healing of the bone graft in one patient even with the occurrence of oral opening, dehiscence, and cutaneous fistula formation. As a result of advanced revascularization, mesenchymal cell migration, fibroblasts and osteoblasts growth, and slow multiplication of bacteria which caused rapid healing, the excellent bony consolidation occurred in the 1st few weeks that the graft was sealed off from the oral cavity.[14]

The goal of mandibular reconstruction is to reshape height and width, whereas the clinical usage of the fibrin glue seems to be easy because of its very simple placement and shaping.[31] Tayapongsak et al.[14] used fibrin glue to guarantee cancellous bone grafts to homologous mandibles during healing. Also, fibrin glue allowed for easier reapproximation of soft tissue following osteoplasties of the mandibular condyle in rabbit model.[61]

Several clinicians have considered that hydroxyapatite granules when fibrin glue is used with them are much more easily handled and are less likely to become displaced.[62,63]

Thorn et al. in 2004 reported that the concentrations of fibrinogen (in platelet-enriched fibrin glue) and growth factors (as measured by platelet-derived growth factor) are approximately 12 and 8 times that of found in platelet-rich plasma, respectively.[31] Marx et al. and Whitman and Berry et al. found that maturation rate of particulate cancellous grafts with platelet growth factors is approximately 2 times that of particulate cancellous grafts without the growth factors.[64,65,66]

In reconstructive bone surgery, the fibrin glue acts as a scaffold for the invasion of cells[67] and as a carrier for bone inductions[68] and can improve the bone graft healing process.[14] A study by Giannini et al. revealed that the presence of numerous growth factors in fibrin glue should enhance the healing potential of the autologous bone graft, probably because of stimulation of the stem cells which are potentially present.[69] Results of another study done by Lee et al. showed that, when a combination of autogenous bone and platelet-enriched fibrin glue is used for maxillary sinus grafting with simultaneous implant placement, the volume of the formed new bone is significantly greater than that of when treated with autogenous bone alone. Furthermore, their study showed that the efficiency of autogenous bone grafting can be improved by the addition of platelet-enriched fibrin glue, and usage of this combination may be effective in improving the height of new bone and the osseointegration of dental implants in sinus floor augmentation with simultaneous implant placement.[70]

Fibrin-stabilizing factor XIII which is found in fibrin glue helps in the migration and proliferation of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells on its highly cross-linked glue structure.[47] An experimental study in sheep done by Claes et al. showed that plasma Factor XIII accelerates bone healing through promotion of fibrin cross-linking, fibroblast proliferation, and enhancing osteoblast activity or proliferation during the first and second phases of fracture healing.[71]

Experimental study in mouse model did not show any presence of inflammation or foreign body giant cells in ceramic implants with fibrin glue, which indicates that healing by this implant with fibrin glue is not eventful.[72] In addition, based on the study done by Giannini et al. in 2004, reduced infections and length of hospital stay of patients treated by fibrin-platelet glue, were observed.[69]

In the bone repair technology, initiation of early osteogenesis is an important criterion and fibrin glue could be a promising candidate.[72] It also improves the remodeling process which begins earlier by accelerating the migration of fibroblast and the revascularization process.[14] Fibrin, because of its stimulatory effect on mesenchymal cells and its angiotropic effect, is suggested as an enhancement of osteogenesis. Osteoblasts around the implants coated with fibrin glue might have originated from the proliferation, differentiation, and migration of the perivascular pericytes and endothelial cells or the mesenchymal stem cells or committed osteoprogenitor cells as observed in periosteal osteogenesis and bone fracture repair.[73,74,75,76] In addition, it has been suggested that fibrin glue can promote osteogenesis in poorly angiogenic components such as ceramics.[77] It is widely used to promote vascularization due to its pro-angiogenic properties.[78]

An experimental study in the mouse model showed successful osteosynthesis without traumatic and toxic conditions 15 days after using fibrin glue-ceramic composite at a nonosseous site.[71] In addition, bone formation was accelerated by the presence of fibrin glue together with the favorable phase composition of bioactive glass system (BGS) and calcium phosphate- calcium silicate system nonporous granules at an ideal implantation site which was concluded that osteoinductive proteins and angiogenic factors can increase cell retention and it is a significant factor in promoting early differentiation of osteogenic cells that was an evidence of the positive role of fibrin glue as a potential osteoinductive biologic tissue adhesive.[71]

Abiraman et al. proposed that a combination of hydroxyapatite and bioactive glass granules coated with fibrin sealant could be an ideal bone graft substitute for regenerative bone surgery because of its osteoinductive properties, and also, easy handling of this component in the operating time.[72]

Lee et al. showed that fibrin glue can be efficacious in delivering mesenchymal stem cells to help bone regeneration in normal and chemotherapy-treated rats.[79] Perka et al.[41] demonstrated a positive effect of periosteal cells seeded into fibrin beads for critical size bone defect reconstruction in rabbits for 28 days, showing this bead can serve well for repairing defects. The construction of three-dimensional templates for bone growth by Yamada et al.[80] showed that application of fibrin glue plus β-tricalcium phosphate and mesenchymal stem cells resulted in new bone formation at heterotopic sites. Recently, a study by Zhou and Xu[81] showed the usefulness of stem cell-encapsulating fibrin microbeads for injection and bone regeneration. In conclusion, cell–fibrin combinations may be efficacious in bone graft replacement due to their potential to induce bone formation.[24]

A study done by Linsley et al. in 2016 showed that hMSCs do not rapidly degrade fibrin and fibrin-collagen scaffolds in vitro. In addition, this study explained that the fibrin scaffolds' stiffness does not significantly change over time and also the construction of fibrin-based engineered tissues and cell delivery vehicles promotes hMSC growth and viability as well as meet the mechanical requirements of native tissues.[82]

The study by Lee et al. showed delivery of mesenchymal stem cells for calvarial defect reconstruction in rabbits with the help of autologous fibrin glue.[32] Their study well demonstrated that, in the presence of MSCs, bone regeneration and reconstruction were better with autologous fibrin glue in comparison to macroporous biphasic calcium phosphate. These results support further research to investigate the use of autologous fibrin glue as a scaffold to enhance bone regeneration in non-weight bearing areas such as craniofacial bones.[6] Therefore, several studies support that autologous fibrin glue can be used as a suitable scaffold in regenerative bone surgery including oral and maxillofacial surgery.

CONCLUSION

Autologous bone graft has been considered a gold standard in the reconstruction of oral and maxillofacial defects, but due to its disadvantages such as a need to provide another surgical site, donor site morbidity and infection, and also movement of bone graft particles during their placement, usage of a good bone graft substitute has been considered. Autologous fibrin glue has been introduced as a scaffold for migrating fibroblasts as well as a hemostatic barrier, stimulates mesenchymal cell, induces and promotes angiogenesis, and also initiates early osteogenesis. These features and additionally its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and easy to use feature make this glue as an interesting scaffold for oral and maxillofacial surgery that may even be a good bone graft substitute.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare that they have no conflicts of interest, real or perceived, financial or non-financial in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrigoni E, Lopa S, de Girolamo L, Stanco D, Brini AT. Isolation, characterization and osteogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells: From small to large animal models. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;338:401–11. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0883-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Z, Li ZB. Repair of mandible defect with tissue engineering bone in rabbits. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:1017–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore WR, Graves SE, Bain GI. Synthetic bone graft substitutes. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:354–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cypher TJ, Grossman JP. Biological principles of bone graft healing. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1996;35:413–7. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(96)80061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suh H, Han DW, Park JC, Lee DH, Lee WS, Han CD. A bone replaceable artificial bone substitute: Osteoinduction by combining with bone inducing agent. Artif Organs. 2001;25:459–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2001.025006459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee OK. Fibrin glue as a vehicle for mesenchymal stem cell delivery in bone regeneration. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71:59–61. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane JM, Sandhu HS. Current approaches to experimental bone grafting. Orthop Clin North Am. 1987;18:213–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920–6. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Guéhennec L, Layrolle P, Daculsi G. A review of bioceramics and fibrin sealant. Eur Cell Mater. 2004;8:1–10. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v008a01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaboe M, Pinholt EM, Hjørting-Hansen E. Healing of experimentally created defects: A review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:312–8. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(95)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mesimäki K, Lindroos B, Törnwall J, Mauno J, Lindqvist C, Kontio R, et al. Novel maxillary reconstruction with ectopic bone formation by GMP adipose stem cells. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haghighat A, Akhavan A, Hashemi-Beni B, Deihimi P, Yadegari A, Heidari F. Adipose derived stem cells for treatment of mandibular bone defects: An autologous study in dogs. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2011;8(Suppl 1):S51–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu T, Wu G, Wismeijer D, Gu Z, Liu Y. Deproteinized bovine bone functionalized with the slow delivery of BMP-2 for the repair of critical-sized bone defects in sheep. Bone. 2013;56:110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tayapongsak P, O'Brien DA, Monteiro CB, Arceo-Diaz LY. Autologous fibrin adhesive in mandibular reconstruction with particulate cancellous bone and marrow. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:161–5. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Behfarnia P, Shahabooei M, Mashhadiabbas F, Fakhari E. Comparison of bone regeneration using three demineralized freeze-dried bone allografts: A histological and histomorphometric study in rabbit calvaria. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:554–60. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.104873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howell SJ, Sear YM, Yeates D, Goldacre M, Sear JW, Foëx P. Risk factors for cardiovascular death after elective surgery under general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:14–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St. John TA, Vaccaro AR, Sah AP, Schaefer M, Berta SC, Albert T, et al. Physical and monetary costs associated with autogenous bone graft harvesting. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2003;32:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon E, Dhar S, Chun DE, Gharibjanian NA, Evans GR. In vivo osteogenic potential of human adipose-derived stem cells/poly lactide-co-glycolic acid constructs for bone regeneration in a rat critical-sized calvarial defect model. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:619–27. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui L, Liu B, Liu G, Zhang W, Cen L, Sun J, et al. Repair of cranial bone defects with adipose derived stem cells and coral scaffold in a canine model. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5477–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt A, van Griensven M, Imhoff AB, Buchmann S. Application of stem cells in orthopedics. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:394962. doi: 10.1155/2012/394962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asadi-Yousefabad SL, Khodakaram-Tafti A, Dianatpour M, Mehrabani D, Zare S, Tamadon A, et al. Genetic evaluation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by a modified karyotyping method. Comp Clin Pathol. 2015;24:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutmacher DW. Scaffolds in tissue engineering bone and cartilage. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2529–43. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salgado AJ, Coutinho OP, Reis RL. Bone tissue engineering: State of the art and future trends. Macromol Biosci. 2004;4:743–65. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de la Puente P, Ludeña D. Cell culture in autologous fibrin scaffolds for applications in tissue engineering. Exp Cell Res. 2014;322:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma K, Titan AL, Stafford M, Zheng CH, Levenston ME. Variations in chondrogenesis of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in fibrin/alginate blended hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:3754–64. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson JM. Biological responses to materials. Annu Rev Mater Res. 2001;31:81–110. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed TA, Dare EV, Hincke M. Fibrin: A versatile scaffold for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:199–215. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasan S, Weinberg M, Khatib O, Jazrawi L, Strauss EJ. The effect of platelet-rich fibrin matrix on rotator cuff healing in a rat model. Int J Sports Med. 2016;37:36–42. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1554637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matras H. Fibrin seal: The state of the art. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:605–11. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dickneite G, Metzner H, Pfeifer T, Kroez M, Witzke G. A comparison of fibrin sealants in relation to their in vitro and in vivo properties. Thromb Res. 2003;112:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorn JJ, Sørensen H, Weis-Fogh U, Andersen M. Autologous fibrin glue with growth factors in reconstructive maxillofacial surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;33:95–100. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2003.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee LT, Kwan PC, Chen YF, Wong YK. Comparison of the effectiveness of autologous fibrin glue and macroporous biphasic calcium phosphate as carriers in the osteogenesis process with or without mesenchymal stem cells. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71:66–73. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang H, Peng S, Chen A, Li F, Ren K, Hu N. Biocompatibility studies on fibrin glue cultured with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2004;24:272–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02832010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tabélé C. Organic glues or fibrin glues from pooled plasma: Efficacy, safety and potential as scaffold delivery systems. J Pharm Sci. 2012;15:124–40. doi: 10.18433/j39k5h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreira Teixeira LS, Leijten JC, Wennink JW, Chatterjea AG, Feijen J, van Blitterswijk CA, et al. The effect of platelet lysate supplementation of a dextran-based hydrogel on cartilage formation. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3651–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matras H, Dinges HP, Lassmann H, Mamoli B. Suture-free interfascicular nerve transplantation in animal experiments. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1972;122:517–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guillotin B, Souquet A, Catros S, Duocastella M, Pippenger B, Bellance S, et al. Laser assisted bioprinting of engineered tissue with high cell density and microscale organization. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7250–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson MR, MacPhee MJ, Drohan WN, Alving BM. Fibrin sealant: Current and potential clinical applications. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1996;7:737–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alving BM, Weinstein MJ, Finlayson JS, Menitove JE, Fratantoni JC. Fibrin sealant: Summary of a conference on characteristics and clinical uses. Transfusion. 1995;35:783–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35996029166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dunn CJ, Goa KL. Fibrin sealant: A review of its use in surgery and endoscopy. Drugs. 1999;58:863–86. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perka C, Schultz O, Spitzer RS, Lindenhayn K, Burmester GR, Sittinger M. Segmental bone repair by tissue-engineered periosteal cell transplants with bioresorbable fleece and fibrin scaffolds in rabbits. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1145–53. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erkan AN, Cakmak O, Kocer NE, Yilmaz I. Effects of fibrin glue on nasal septal tissues. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:491–6. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31802dc5bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gosk J, Knakiewicz M, Wiacek R, Reichert P. The use of the fibrin glue in the peripheral nerves reconstructions. Polim Med. 2006;36:11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu C, Xia Z, Czernuszka J. Design and development of three-dimensional scaffolds for tissue engineering. Chem Eng Res Des. 2007;85:1051–64. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Isogai N, Landis WJ, Mori R, Gotoh Y, Gerstenfeld LC, Upton J, et al. Experimental use of fibrin glue to induce site-directed osteogenesis from cultured periosteal cells. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:953–63. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200003000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khodakaram-Tafti A, Mehrabani D, Shaterzadeh-Yazdi H. Autologous Fibrin Glue as a Suitable Scaffold for Bone Tissue Engineering. International Congress on Stem Cells & Regenerative Medicine. Mashhad. Iran. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ito K, Yamada Y, Naiki T, Ueda M. Simultaneous implant placement and bone regeneration around dental implants using tissue-engineered bone with fibrin glue, mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:579–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silver FH, Wang MC, Pins GD. Preparation and use of fibrin glue in surgery. Biomaterials. 1995;16:891–903. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)93113-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de la Puente P, Ludeña D, Fernández A, Aranda JL, Varela G, Iglesias J. Autologous fibrin scaffolds cultured dermal fibroblasts and enriched with encapsulated bFGF for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2011;99:648–54. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barsotti MC, Magera A, Armani C, Chiellini F, Felice F, Dinucci D, et al. Fibrin acts as biomimetic niche inducing both differentiation and stem cell marker expression of early human endothelial progenitor cells. Cell Prolif. 2011;44:33–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de la Puente P, Ludeña D, López M, Ramos J, Iglesias J. Differentiation within autologous fibrin scaffolds of porcine dermal cells with the mesenchymal stem cell phenotype. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:144–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briganti E, Spiller D, Mirtelli C, Kull S, Counoupas C, Losi P, et al. A composite fibrin-based scaffold for controlled delivery of bioactive pro-angiogenetic growth factors. J Control Release. 2010;142:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zisch AH, Schenk U, Schense JC, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Hubbell JA. Covalently conjugated VEGF – fibrin matrices for endothelialization. J Control Release. 2001;72:101–13. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jeon O, Ryu SH, Chung JH, Kim BS. Control of basic fibroblast growth factor release from fibrin gel with heparin and concentrations of fibrinogen and thrombin. J Control Release. 2005;105:249–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matras H. The use of fibrin sealant in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982;40:617–22. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(82)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Y, Li R, Hu J, Song D, Jiang X, Zhu S. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 suspended in fibrin glue enhances bone formation during distraction osteogenesis in rabbits. Arch Med Sci. 2016;12:494–501. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2016.59922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keller J, Andreassen TT, Joyce F, Knudsen VE, Jørgensen PH, Lucht U. Fixation of osteochondral fractures. Fibrin sealant tested in dogs. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56:323–6. doi: 10.3109/17453678508993025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pini Prato GP, Cortellini P, Agudio G, Clauser C. Human fibrin glue versus sutures in periodontal surgery. J Periodontol. 1987;58:426–31. doi: 10.1902/jop.1987.58.6.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baudo F, deCataldo F, Landonio G, Muti G. Management of oral bleeding in haemophilic patients. Lancet. 1988;2:1082. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bösch P, Lintner F, Arbes H, Brand G. Experimental investigations of the effect of the fibrin adhesive on the Kiel heterologous bone graft. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1980;96:177–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00457781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kurita K, Westesson PL, Eriksson L, Sternby NH. Osteoplasty of the mandibular condyle with preservation of the articular soft tissue cover: Comparison of fibrin sealant and sutures for fixation of the articular soft tissue cover in rabbits. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;69:661–7. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90343-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim YS, Choi YJ, Suh DS, Heo DB, Kim YI, Ryu JS, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell implantation in osteoarthritic knees: Is fibrin glue effective as a scaffold? Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:176–85. doi: 10.1177/0363546514554190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davis BR, Sándor GK. Use of fibrin glue in maxillofacial surgery. J Otolaryngol. 1998;27:107–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marx RE, Carlson ER, Eichstaedt RM, Schimmele SR, Strauss JE, Georgeff KR. Platelet-rich plasma: Growth factor enhancement for bone grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:638–46. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whitman DH, Berry RL, Green DM. Platelet gel: An autologous alternative to fibrin glue with applications in oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1997;55:1294–9. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(97)90187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whitman DH, Berry RL. A technique for improving the handling of particulate cancellous bone and marrow grafts using platelet gel. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:1217–8. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(98)90776-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Knox P, Crooks S, Rimmer CS. Role of fibronectin in the migration of fibroblasts into plasma clots. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:2318–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.6.2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kawamura M, Urist MR. Human fibrin is a physiologic delivery system for bone morphogenetic protein. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;235:302–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giannini G, Mauro V, Agostino T, Gianfranco B. Use of autologous fibrin-platelet glue and bone fragments in maxillofacial surgery. Transfus Apher Sci. 2004;30:139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee HJ, Choi BH, Jung JH, Zhu SJ, Lee SH, Huh JY, et al. Maxillary sinus floor augmentation using autogenous bone grafts and platelet-enriched fibrin glue with simultaneous implant placement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:329–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Claes L, Burri C, Gerngross H, Mutschler W. Bone healing stimulated by plasma factor XIII. Osteotomy experiments in sheep. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56:57–62. doi: 10.3109/17453678508992981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abiraman S, Varma HK, Umashankar PR, John A. Fibrin glue as an osteoinductive protein in a mouse model. Biomaterials. 2002;23:3023–31. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Diaz-Flores L, Gutierrez R, Lopez-Alonso A, Gonzalez R, Varela H. Pericytes as a supplementary source of osteoblasts in periosteal osteogenesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:280–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brighton CT, Hunt RM. Early histological and ultrastructural changes in medullary fracture callus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:832–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Urist MR, DeLange RJ, Finerman GA. Bone cell differentiation and growth factors. Science. 1983;220:680–6. doi: 10.1126/science.6403986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mishra R, Roux BM, Posukonis M, Bodamer E, Brey EM, Fisher JP, et al. Effect of prevascularization on in vivo vascularization of poly(propylene fumarate)/fibrin scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2016;77:255–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ripamonti U, Van den Heever B, Van Wyk J. Expression of the osteogenic phenotype in porous hydroxyapatite implanted extraskeletally in baboons. Matrix. 1993;13:491–502. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schlag G, Redl H. Fibrin sealant in orthopedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;227:269–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee OK, Coathup MJ, Goodship AE, Blunn GW. Use of mesenchymal stem cells to facilitate bone regeneration in normal and chemotherapy-treated rats. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1727–35. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamada Y, Boo JS, Ozawa R, Nagasaka T, Okazaki Y, Hata K, et al. Bone regeneration following injection of mesenchymal stem cells and fibrin glue with a biodegradable scaffold. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(02)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou H, Xu HH. The fast release of stem cells from alginate-fibrin microbeads in injectable scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7503–13. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Linsley CS, Wu BM, Tawil B. Mesenchymal stem cell growth on and mechanical properties of fibrin-based biomimetic bone scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2016;104:2945–53. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]