Abstract

Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) strains are genetically variable and virulence factors for AIEC are non-specific. FimH is the most studied pathogenicity-related protein, and there have been few studies on other proteins, such as Serine Protease Autotransporters of Enterobacteriacea (SPATEs). The goal of this study is to characterize E. coli strains isolated from patients with Crohn's disease (CD) in Chile and Spain, and identify genetic differences between strains associated with virulence markers and clonality. We characterized virulence factors and genetic variability by pulse field electrophoresis (PFGE) in 50 E. coli strains isolated from Chilean and Spanish patients with CD, and also determined which of these strains presented an AIEC phenotype. Twenty-six E. coli strains from control patients were also included. PFGE patterns were heterogeneous and we also observed a highly diverse profile of virulence genes among all E. coli strains obtained from patients with CD, including those strains defined as AIEC. Two iron transporter genes chuA, and irp2, were detected in various combinations in 68–84% of CD strains. We found that the most significant individual E. coli genetic marker associated with CD E. coli strains was chuA. In addition, patho-adaptative fimH mutations were absent in some of the highly adherent and invasive strains. The fimH adhesin, the iron transporter irp2, and Class-2 SPATEs did not show a significant association with CD strains. The V27A fimH mutation was detected in the most CD strains. This study highlights the genetic variability of E. coli CD strains from two distinct geographic origins, most of them affiliated with the B2 or D E. coli phylogroups and also reveals that nearly 40% of Chilean and Spanish CD patients are colonized with E.coli with a characteristic AIEC phenotype.

Keywords: adherent invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), clonal relationship, Crohn's disease, biopsy, virulence genes, fimH mutations, SPATEs

Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) is characterized by chronic inflammation of different sections of the gastrointestinal tract. The etiology of CD is unknown but it has been hypothesized that the interplay of diverse factors, including the intestinal microbiota, genetic, and immunologic host factors, as well as environmental cues, are responsible for its etiology (Kaser et al., 2010). Escherichia coli has been shown to occur more often in the gastrointestinal mucosa of patients with CD as compared to non-CD individuals, leading the hypothesis that this microorganism may play a major role in the development of CD (Darfeuille-Michaud et al., 1998, 2004; Schultsz et al., 1999; Ryan et al., 2004; De la Fuente et al., 2014). Furthermore, many of the strains isolated from patients with CD display properties consistent with those exhibited by strains of the adherent-invasive E. coli pathotype (AIEC). AIEC strains are able to adhere to and invade epithelial cells, to colonize the intestinal epithelium, and to survive intracellularly in macrophages (Darfeuille-Michaud et al., 1998; Boudeau et al., 1999; Glasser et al., 2001; De la Fuente et al., 2014). The virulence factors harbored by AIEC strains differ from those characteristic of other groups of diarrheagenic E. coli strains (Darfeuille-Michaud et al., 1998; Boudeau et al., 1999; Glasser et al., 2001; De la Fuente et al., 2014).

One of the most studied virulence factors in AIEC strains is fimH. This gene encodes an adhesin located at the tip of the Type 1 pili; FimH mediates bacterial adhesion to glycosylated and non-glycosylated host receptors, including the matrix-associated type I and IV collagens, laminin, fibronectin, and glycosylated receptors (Sokurenko et al., 1997). AIEC that adhere to ileal enterocytes via FimH recognize the carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 6 (CEACAM-6) receptor, which appears to be overexpressed in the ileal epithelial cells of patients with CD (Barnich et al., 2007). In addition, polymorphisms in fimH confer a higher ability to adhere to CEACAM-6 (Dreux et al., 2013).

Vat-AIEC (Vacuolating autotransporter toxin), a Serine Protease Autotransporters of Enterobacteriacea (SPATE) that promotes crossing of the intestinal mucus layer by the LF82 AIEC strain, was recently identified (Gibold et al., 2016). SPATEs constitute a superfamily of trypsin-like serine proteases; they are highly prevalent and are generally secreted by enteropathogens (Yen et al., 2008; Ruiz-Perez and Nataro, 2014). SPATEs have been classified into two groups, class-1 and class-2, based on the amino acidic sequence of their passenger domain and the different functions they perform (Dutta et al., 2002; Ruiz-Perez and Nataro, 2014). To date, class-1 SPATEs have been reported to display cytotoxic effects on cultured cells and enterotoxin activity on intestinal tissues (Boisen et al., 2009; Ruiz-Perez and Nataro, 2014). Most class-2 SPATEs studied display mucinase activity and cleave a variety of leukocyte surface glycoproteins (Ruiz-Perez and Nataro, 2014). The prevalence and possible role of both class-1 and class-2 SPATEs in AIEC strains has received little attention in the literature.

The aims of the present study were to evaluate the genetic variability of 50 E. coli isolates from intestinal biopsies of patients with CD in Chile and Spain and 26 isolates from non-CD subjects, to determine the presence of virulence factors typically found in AIEC strains and in strains associated with CD, and to study E. coli strains' affiliation with the different phylogenetic groups (A, B1, B2, and D). We also compared the presence of class-1 and class-2 SPATEs and polymorphisms in fimH gene, between CD and non-CD E. coli isolates.

Methods

We analyzed 50 E. coli strains obtained from patients diagnosed with CD and 26 strains from non-CD patients of which 15 were obtained from subjects who were submitted to colonoscopy for either constipation, anal bleeding, or colon cancer evaluations and had normal colonoscopy results, and 11 were obtained from the feces of normal individuals (Table 1). Forty nine strains (35 from CD and 14 from non-CD patients) were isolated from biopsies taken from 16 patients who underwent colonoscopy at the Son Espases Reference Hospital (Mallorca, Spain) between August 2011 and March 2012; the microbiome of these patients was previously described using molecular methods (Vidal et al., 2015) (Table 1). The Chilean strains were represented by 27 isolates (15 from CD, 1 from a non-CD patient) obtained from patients who underwent colonoscopy at Clínica Las Condes in Santiago, Chile between July 2010 and January 2011, and 11 strains isolated from feces samples of healthy patients (Table 1). All strains isolated from patient biopsies were obtained as previously described (De la Fuente et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Description of the two patients groups, Crohn's Disease and Controls, and the number and type of Escherichia coli isolates.

| Patient IDa | E. coli strains isolate | Birth year | Originb | Year of CD Diagnosis | Locationc | Behaviord | Surgery | Medication (at least 3 months before sampling) | Clinical statuse | Colonoscopy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD PATIENTS | ||||||||||

| 1C | 1I06 | 1975 | S | 2002 | L3 | B3 | Ileocolic resection | Immunosuppressive agent | Clinical activity | Anastomotic stenosis with ulcers |

| 2C | 2C05, 2I05 | 1963 | S | 1983 | L3 | B3 | Ileal resection | Immunosuppressive agent | Remission | Normal colon and ileum |

| 4C | 4C01, 4I03, 4I01 | 1955 | S | 1990 | L1 | B2 | Ileocolic resection | 5-aminosalicylates | Remission | Normal colon, anastomotic stenosis |

| 5C | 5I01, 5C08 | 1992 | S | 2005 | L3 | B2 | Ileocolic | Immunosuppressive agent | Clinical activity | Normal colon anastomotic |

| 6C | 6I01, 6I02, 6I06, 6I07, 6I09, 6I10, 6C03, 6C04, 6C09, 6C10 | 1958 | S | 2011 | L2 | B2 | Ileocolic resection | 5-aminosalicylates | Remission | Normal colon and ileum |

| 7C | 7C08, 7C09, 7C02, 7C04, 7C06, 7C07 | 1983 | S | 2005 | L3 | B2 | NS | TNF antagononist | Remission | Inflammatory activity in colon and stenosis |

| 9C | 9C01, 9C02 | 1976 | S | 1984 | L1 | B3 | Ileocolic | TNF antagononist | – | Inflammatory activity in ileum |

| 10C | 10C01, 10C05, 10I01, 10I03 | 1949 | S | 1997 | L1 | B1 | Ileocolic | 5-aminosalicylates | Clinical activity | Normal colon Anastomotic |

| 18C | 18I08, 18I02, 18C01, 18C02 | 1940 | S | 1940 | L1 | B3 | Ileocolic | Immunosuppressive agent | Clinical activity | Normal colon |

| 24C | 24C01 | 1989 | S | 2009 | L1 | B3 | Ileocolic resection | Immunosuppressive agent | Remission | Normal colon, anastomotic stenosis |

| CD43 | PT1 | 1960 | CH | 1988 | L3 | B2 | NS | NM | Clinical activity | Ileal and colonic ulcers and colon with stenosis |

| CD45 | JSL | 1970 | CH | 2002 | L3 | B1 | NS | Immunosuppressive agent | Remission | Normal colon and ileum |

| CD44 | EII | 1985 | CH | 2008 | L2 | B1 | NS | TNF antagononist | Clinical activity | Normal colon and ileum |

| CD37 | GM | 1980 | CH | 2012 | L1 | B1 | Ileal resection | Immunosuppressive agent | Clinical activity | Ileal ulcers Anastomotic |

| CD19 | FBC | 1982 | CH | 2009 | L3 | B1 | NS | Immunosuppressive agent | Clinical activity | Ileal and rectal ulcers Anastomotic |

| CD18 | CPA | 1970 | CH | ND | L1 | B2 | NS | – | Clinical activity | – |

| CD1 | CD1-a | 1927 | CH | ND | L2 | B1 | – | NM | Clinical activity | Rectosigmoiditis |

| CD2 | CD2-a | 1966 | CH | ND | L2 | B1 | – | NM | No Clinical activity | Normal colon and ileum |

| CD6 | CD6-b, CD6-r | 1955 | CH | ND | L2 | B1 | – | Immunosuppressive agent | Clinical activity | Diverticulosis Perianal fistula |

| CD8 | CD8-a | 1961 | CH | ND | L2 | B2 | – | Clinical activity | Colon with stenosis Perianal fistula | |

| CD9 | CD9-a | 1969 | CH | ND | L2 | B1 | – | Anti-inflammatory | Clinical activity | Colitis in the distal segment |

| CD12 | CD12-a | 1984 | CH | ND | L2 | B1 | – | – | Clinical activity | Edematous colonic lesions |

| CD13 | CD13-a | 1989 | CH | ND | L3 | B1 | – | – | Clinical activity | Colon and ileum active |

| CD14 | CD14-a | 1985 | CH | ND | L3 | B1 | – | – | No Clinical activity | Closed fistula |

| CONTROL PATIENTS | ||||||||||

| 14S | 14I01, 14I02, 14C01, 14C05, 14C06, 14C09 | 1952 | S | Control | Constipation | Normal colon | ||||

| 15S | 15C02 | 1965 | S | Control | Constipation | Normal colon | ||||

| 16S | 16C01, 16C02 | 1945 | S | Control | Hemorrhoid | Normal colon | ||||

| 19S | 19C01, 19C02 | Control | ||||||||

| 22S | 22C02, 22C05 | 1938 | S | Control | Hemorrhoid | Normal colon | ||||

| 23S | 23C01 | 1961 | S | Control | RCC screening | Normal colon | ||||

| C7 | C7-a | 1940 | CH | Control | Normal colon | |||||

| D1-D11 | D1, D2, D3, D4, D5, D6, D7, D8, D9, D10, D11 | CH | Control | Stool samples | Normal colon | |||||

CD, Crohn's Disease.

Patient ID underlined indicate that they had E. coli strains whose phenotype corresponded to AIEC.

Origin, S-Spain; CH-Chile.

Location, L1-Ileal; L2-Colonic; L3-Ileocolonic.

Behavior, B1-inflammatory; B2-stricture; B3-penetrant disease.

Clinical status, Clinical activity; No Clinical activity; Remission.

RCC, rectal colon cancer; NS, no surgery; NM, no medication; ND, no data; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor.

All CD Chilean strains were obtained from ileum biopsies. Almost all Chilean control strains were obtained from stool samples and only one (C7) from an ileum biopsy. The Spanish strains were obtained from colon (C) or ileum (I) biopsies.

Briefly, biopsy samples were suspended in GIBCO® Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 100 μg/ml gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO, USA), incubated for 1 h at 37°C and then washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in 100 μl of 1% Triton-X-100/PBS to release intracellular bacteria. The homogenized tissue obtained was plated on MacConkey agar (Oxoid Ltd.; Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Determination and confirmation of E. coli identification was first performed using biochemical tests and then by PCR. Study participants provided written informed consent before entering the study. The project and informed consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Clínica Las Condes; Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de Chile; Ethics Committee of the Northern Metropolitan Health Service, Santiago, Chile; and the Balearic Islands' Ethical Committee, Spain. All records and information was kept confidential and all identifiers were removed prior to analysis.

E. coli K-12, NRG857c (Nash et al., 2010), K-12, HS (DuPont et al., 1971; Levine et al., 1978), and HM605 (Clarke et al., 2011) were included as reference strains. All strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) agar or LB broth (BD Diagnostics; Sparks Glencoe, MD, USA) at 37°C for 18 h.

PFGE was performed according to the protocol described on the PulseNet website of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, using XbaI and SpeI restriction enzymes (CDC; http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/PDF/ecoli-shigella-salmonella-pfge-protocol-508c.pdf). The genetic variability of the CD E. coli strains including reference strains HS, reference AIEC strains NRG857c and HM605 (kindly provided by A. Torres and I. Henderson, respectively) and non-CD strains was analyzed by pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). A Salmonella enterica serotype Braenderup (H9812 strain) was used as a gel loading control. PFGE patterns were analyzed with the GEL COMPAR II software (Applied Maths), using the Dice similarity coefficient with a 0.9 % tolerance in band position. Phylogenetic affiliation (A, B1, B2, or D groups) was performed using a previously described method (Clermont et al., 2000). Virulence genotyping was determined by amplifying the following virulence-associated genes commonly present in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC): cnf1, hlyA, cdtB, neuC, ibeA, papC, sfa/focDE, afa/draBC, fimH, and fimAvMT78 (Martinez-Medina et al., 2009), as well as other pathogenicity-associated factors, such as the adhesin synthesis gene (aufA), toxins (ratA, cvaC), iron uptake (irp2, fhuD, and chuA), and Peyer's patch survival (gipA). PCR primers used for gene amplification are detailed in Table 2 and PCR amplifications were performed under standard conditions, as previously described (Martinez-Medina et al., 2009).

Table 2.

Primers used to PCR analyses for adhesins, iron uptake proteins, toxins, E. coli phylogenetics groups, SPATEs, and others virulence factors.

| Primer sequences (5′–3′) | Target sequences | References |

|---|---|---|

| ADHESIN | ||

| afaBC-F: GCTGGGCAGCAAACTGATAACTCTC | Afimbrial adhesin | Le Bouguenec et al., 1992 |

| afaBC-R: CATCAAGCTGTTTGTTCGTCCGCCG | ||

| aufA-F: TTGGTGGGGCGGATACTGAC | Putative fimbrial-like protein | This study |

| aufA-R: TGTATAAGCGGCGGTGGAGG | ||

| fimAv MT78-F: TCTGGCTGATACTACACC | Variant form of the type 1 major fimbrial subunit | Marc and Dho-Moulin, 1996 |

| fimAv MT78-R: ACTTTAGGATGAGTACTG | ||

| fimH-F: GATCTTTCGACGCAAATC | Adhesin of type 1 fimbriae | Arne et al., 2000 |

| fimH-R: CGAGCAGAAACATCGCAG | ||

| papC-F: GACGGCTGTACTGCAGGGTGTGGCG | Pyelonephritis associated pili | Le Bouguenec et al., 1992 |

| papC-R: ATATCCTTTCTGCAGGGATGCAATA | ||

| sfa/focDE-F: CTCCGGAGAACTGGGTGCATCTTAC | S-fimbrial and F1C fimbriae dhesion | Le Bouguenec et al., 1992 |

| sfa/focDE-R:CGGAGGAGTAATTACAAACCTGGCA | ||

| IRON ACQUISITION | ||

| chuA-F:TATGATGGTCAGCGTTATCGAC | Outer membrane hemin receptor | This study |

| chuA-R: CATAGCCAGGTTGTTTGCTGTA | ||

| fhuD-F: AACCTTGAACTGCTGACCGAAAT | Component of the ferric hydroxamate uptake (Fhu) system | This study |

| fhuD-R: GTACTGCCCCAGAAGTTGGTTTC | ||

| irp2-F: CGCAGAATCGCTGTTAGCAC | Iron regulatory protein 2 | This study |

| irp2-R: TGGTAGCGATCTTCAGGGGA | ||

| TOXINS | ||

| cdtB-F: GAAAGTAAATGGAATATAAATGTCCG | Cytolethal distending toxin, subunit B | Johnson and Stell, 2000 |

| cdtB-R: AAATCACCAAGAATCATCCAGTTA | ||

| cnfI-F: AAGATGGAGTTTCCTATGCAGGAG | Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 | Yamamoto et al., 1995 |

| cnfI-R: CATTCAGAGTCCTGCCCTCATTATT | ||

| cvaC-F: CACACACAAACGGGAGCTGTT | Gene codes for the structural gene for colicin V α-Hemolysin | Johnson and Stell, 2000 |

| cvaC-R: CTTCCCGCAGCATAGTTCCAT | ||

| hlyA-F: AACAAGGATAAGCACTGTTCTGGCT | Alfa hemolysin | Yamamoto et al., 1995 |

| hlyA-R: ACCATATAAGCGGTCATTCCCGTCA | ||

| ratA-F: CCGTCATTTTCGCCGCACCT | Ribosome association toxin | This study |

| ratA-R: ACCCACAGCCAGTCGCAGAT | ||

| OTHERS VIRULENCE GENES | ||

| ibeA-F: AGGCAGGTGTGCGCCGCGTAC | Invasion of brain endothelial (IbeA) protein (invasin) | Johnson and Stell, 2000 |

| ibeA-R: TGGTGCTCCGGCAAACCATGC | ||

| gipA-F: TTCCCCTCCAGCAGTCGTTG | Peyer's patch-specific factor | This study |

| gipA-R: GAACATCCAGCGGCGACTTG | ||

| neuCK1-F: AGGTGAAAAGCCTGGTAGTGTG | K1 capsular polysaccharide | Watt et al., 2003 |

| neuCK1-R: GGTGGTACATTCCGGGATGTC | ||

| pduC-F: GTTGCCGTTGCTCGCTATGC | Coenzyme B12-dependent 1,2-propanediol catabolism | This study |

| pduC-R: ACTGCACGGATGCCTGATGG | ||

| E. coli PHYLOGENETIC GROUPS | ||

| chuA.1: GACGAACCAACGGTCAGGAT | Outer membrane hemin receptor | Clermont et al., 2000 |

| chuA.2: TGCCGCCAGTACCAAAGACA | ||

| yjaA.1: TGAAGTGTCAGGAGACGCTG | Coding for protein of unknown function | Clermont et al., 2000 |

| yjaA.2: ATGGAGAATGCGTTCCTCAAC | ||

| tspE4C2.1: GAGTAATGTCGGGGCATTCA | Tsp encodes for a putative DNAfragment (TSPE4.C2) in E. coli | Clermont et al., 2000 |

| tspE4C2.2: CGCGCCAACAAAGTATTACG | ||

| SPATEs CLASS-1 (Cl-1) | ||

| Sat1: TCAGAAGCTCAGCGAATCATTG | Secreted autotransporter toxin | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| Sat2: CATTATCACCAGTAAAACGCACC | ||

| sigA 1: CCGACTTCTCACTTTCTCCCG | Exported serine protease SigA | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| sigA 2: CCATCCAGCTGCATAGTGTTTG | ||

| pet 1: GGCACAGAAT AAAGGGGTGTTT | Plasmid-encoded toxin | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| pet 2: CCTCTTGTTTCCACGACATAC | ||

| espP 1: GTCCATGCAGGGACATGCCA | Extracellular serine protease | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| espP 2: TCACATCAGCACCGTTCTCTAT | ||

| espC 1: AGTGCAGTGCAGAAAGCAGTT | Plasmid (pO157)-encoded) | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| espC 2: AGTTTTCCTGTTGCTGTATGCC | EPEC secreted protein C | |

| SPATEs CLASS-2(Cl-2) | ||

| pic 1: ACTGGATCTTAAGGCTCAGGAT | Protease involved in intestinal colonization | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| pic 2: GACTTAATGTCACTGTTCAGCG | ||

| sepA 1: GCAGTGGAAATATGATGCGGC | Shigella extracellular protein A | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| sepA 2: TGTTCAGATCGGAGAAGAACG | ||

| tsh 1: CCGTACACAAATACGACGG | Temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| tsh 2: GGATGCCCCTGCAGCGT | ||

| vat 1: AACGGTTGGTGGCAACAATCC | Vacuolating autotransporter toxin | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| vat 2: AGCCCTGTAGAATGGCGAGTA | ||

| eatA1:CAGGAGTGGGAACATTAAGTCA | Autotransporter protein of enterotoxigenic E. coli. | Boisen et al., 2009 |

| eatA 2: CGTACGCCTTTGATTTCAGGAT | ||

| EaaA1: GAAGACGAACTGGTTTACGGTG | EaaA from Prophage P-EibA | This study |

| EaaA 2: GTGGCATTATCAGCATCAATATC | ||

| EcNA114 1: ACTCAGACATGGAAAGGCGGC | EcNA114-C2sp From UPEC NA144 | This study |

| EcNA114 2: CTCCAGTGATGATCCCACCC | ||

Class-1 (sat, pet, sigA, espP, espC) and class-2 (sepA, eatA, vat, tsh, pic, eaaA, ecNA144) SPATEs (Dutta et al., 2002; Ruiz-Perez and Nataro, 2014) were PCR detected using previously described primers (Boisen et al., 2009), as well as others described in Table 2.

AIEC strains are characterized by their ability to: (i) adhere to epithelial cells, (ii) invade epithelial cells, and (iii) survive intracellularly in macrophages (Darfeuille-Michaud et al., 1998; Boudeau et al., 1999; Glasser et al., 2001; De la Fuente et al., 2014). Analysis of adhesion and invasion in epithelial cells properties was performed as previously described (Boudeau et al., 1999). Briefly, duplicate 24-well plates containing confluent monolayers of Caco-2 cells were infected at a 10:1 multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 30 min at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cell monolayers were washed three times with PBS, and the adherent bacteria were harvested by lysis with 0.1% Triton X-100, serially diluted and plated on LB agar plates. Results are expressed as the percent of adherent bacteria with respect to the total bacteria present after infection (planktonic bacteria plus adherent bacteria). For the invasion assay, the cell monolayer, previously infected for 30 min, was washed three times and then incubated for 3 h with medium containing 100 μg of amikacin/ml. After 3 h, the cell monolayer was washed three times with PBS and bacteria were harvested by lysis with 0.1% Triton X-100. Bacteria were considered able to survive when the ratio between the number of intracellular bacteria and initial inoculums was ≥ 0.1%.

Analysis of survival and replication of the strains in urine RAW 264.7 macrophages were done according to Glasser et al. (2001) with some modifications. Confluent monolayers of murine RAW 264.7 macrophages were infected at a 10:1 MOI for 2 h and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After 2 h of incubation, the cell monolayer was washed three times with PBS, and then incubated for 1 h with medium containing 100 μg of amikacin/ml. Three and 24 h post-infection, the cell monolayer was washed with PBS and bacteria were harvested by lysis with 0.1% Triton X-100. The number of CFU/ml recovered was determined. Bacteria were considered invasive when the ratio between the number of intracellular bacteria and initial inoculum was ≥0.1%, and considered able to survive when the number of intracellular bacteria recovered at 24 h was comparable to that recovered at 3 h post infection (100%) or similar to those obtained for reference AIEC strains. In addition, E. coli strain isolated form CD that was recovered with a similar or higher ratio than NRG857c and HM605, was considered able to replicate intracellularly. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Amplification of fimH was conducted with fimH-F and fimH-R primers (Table 2) using High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA). PCR products were purified, following the manufacturer's instructions (EZNA gel extraction kit, Omega Bio-Tek; Norcross, GA, USA), cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega; Madison, WI, USA), and then sequenced by MACROGEN (Rockville, MD, USA). The fimH nucleotide sequences were translated to protein sequences and compared to orthologous protein sequences. Phylogenetic reconstruction based on FimH protein sequences was obtained by Kimura 2-parameter method and a phylogenetic tree was plotted using the nearest-neighbor joining method in MEGA software, version 6.0.

We considered adhesins, iron-transporters, and toxins along with other virulence factors as potential biomarker candidates for CD or AIEC strains phenotype. The association between these candidates and Crohn's disease was statistically estimated using hypothesis testing. We decided to test for biomarkers using by two tests: the Chi-squared independence and proportions comparison, and Odds Ratio (OR) computations. Estimations and computations were performed at VassarStats statistical computation website (http://vassarstats.net/index.html).

Results

Genomic types among E. coli strains

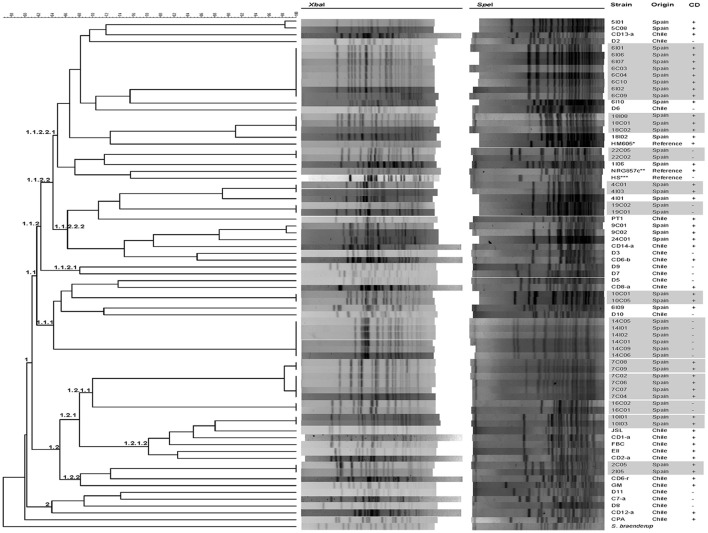

A set of 76 strains obtained from 24 patients with CD and 18 non-CD patients were included in the present study (Table 1). Seventy one strains were initially selected and analyzed by PFGE using XbaI and SpeI restriction enzymes. Two main groups (clusters 1 and 2) composed of 70 strains were separated with similarity values >60%. One Chilean strain (CPA) was separated from the other E. coli strains studied (Figure 1). The larger cluster (Cluster 1, 66/70) is subdivided into two smaller groups, cluster 1.1, which contains most of the CD and non-CD strains and cluster 1.2, which is composed of 17 CD strains and 2 clonal non-CD strains (16C02 and 16C01). AIEC reference strains NRG857c and HM605 were placed in two branches of cluster 1.1.2.2.1. The smaller cluster (Cluster 2, 4/70), is composed of three non-CD strains (D11, D8 and C7-a) and one CD strain (CD12-a).

Figure 1.

Clonal relationship between Escherichia coli strains obtained from intestinal biopsies from patients with CD, biopsies or stool from non-CD patients and reference strains. The dendrogram based on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using the XbaI and SpeI enzymes, allowed the identification of two main groups. Crosses indicate strains isolated from Crohn's disease patients. Clonal related strains are gray shadows highlighted. The reference strains used (Reference) were (*) HM605 (AIEC), (**) NRG857c (AIEC) and (***) HS (commensal E. coli).

In almost all strains, pattern diversity was remarkable, and non-clonal varieties (i.e., identical profiles) were observed, with the exception of PFGE pattern types of strains isolates within a single patient, which were clonal or closely related (i.e., 14C05, 14I01, 14I02, 14C01, 14C06, and 14C09 isolated from patient 14S; 6I01, 6I06, 6I07, 6C03, 6C04, 6C10, 6I02, and 6I09 isolated from patient 6C; 10C01 and 10C05 isolated from patient 10C; 18I08, 18C01 and 18C02 isolated from patient 18C; 4C01, 4I03 isolated from patient 4C; 19C02, 19C01 isolated from patient 19S; 16C02 and 16C01 isolated from patient 16S; 10I01 and 10I03 isolated from patient 10C; 7C08 and 7C09; 7C02,7C06,7C07, 7C04 isolated from patient 7C; 22C05 and 22C02 isolated from patient 22S; 2C05 and 2I05 isolated from patient 2C). From each group of clonal strains, a single strain was selected for further analysis, resulting in 32 non-clonal CD-strains and 18 non-CD (commensal E. coli) strains. Of these 32 strains isolated from patients with CD, 13 were of an AIEC phenotype (Table 3). There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the prevalence of AIECs between Spanish (41.1%, 7/17) and Chilean strains (40%, 6/15).

Table 3.

Phylogenetic groups and virulence genes detected by PCR in Escherichia coli strains isolated from Crohn's disease and control patients (non-CD strains).

| Strains | phylogroup | flmH | aufA | papC | fimAv | afaBC | Sfa/focDE | fhuD | chuA | irp2 | ratA | cvaC | hlyA | cnfl | cdtB | pduC | neuCk1 | gipA | ibeA | Cl-1 | Cl-2 | AlEC phenotype | Surgery | Immunosupressive agent | Medication IFN-γ | Clinical activity | Remission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPANISH STRAINS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1I06 | D | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | – |

| 2C05 | B2 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | + |

| 4C01 | B2 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| 4I01 | B2 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| 5C08 | B1 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | – |

| 5I01 | B2 | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | – |

| 6I01 | B2 | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | + |

| 6I09 | D | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | + |

| 6I10 | D | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | + |

| 7C02 | D | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | – | + |

| 7C08 | D | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + |

| 9C01 | B2 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – |

| 10C01 | D | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | – |

| 10I01 | D | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | – |

| 18I02 | B2 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | + | – | + | – |

| 18I08 | B2 | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | – |

| 24C01 | B2 | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | + |

| CHILEAN STRAINS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CD1–a | D | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | + | NI | – | – | + | – |

| CD2–a | D | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | + | NI | – | – | – | + |

| CD6–b | B2 | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | NI | + | – | + | – |

| CD6–r | D | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | NI | + | – | + | – |

| CD8–a | A | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NI | NI | NI | + | – |

| CD9–a | A | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | NI | + | – | + | – |

| CD12–a | A | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NI | NI | NI | + | – |

| CD13–a | A | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NI | NI | NI | + | – |

| CD14–a | B2 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | NI | NI | NI | – | + |

| JSL | D | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + |

| E11 | D | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – |

| GM | D | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | + | – | + | – |

| PT1 | B2 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – |

| FBC | D | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | + | – |

| CPA | D | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | NI | NI | + | – |

| AIEC TYPE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HM605 | B2 | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| NRG857c | B2 | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI |

| NON–CD STRAINS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| D1* | B1 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D2* | B1 | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D3* | B2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D4* | B1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D5* | B2 | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D6* | D | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D7* | A | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D8* | A | + | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D9* | A | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D10* | D | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D11* | A | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| C7–a** | A | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 14C05** | B1 | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 15C02** | D | + | – | – | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 16C02** | A | + | + | – | – | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 19C01** | B2 | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 22C05** | B2 | + | + | – | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 23C01** | A | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| COMMENSAL TYPE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HS | A | + | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

NI, without information.

Non-CD strains from Chile.

Non-CD strains from Spain.

The dendrogram (Figure 1) revealed that even strain from the same geographic origin appeared intermixed as they did not group according to their origin. In addition, most E. coli clinical isolates-derived from patients with CD were associated with B2 and D genomic types (accounting for 84% of all strains, 27/32, p < 0.05). A very small percentage of CD strains were clustered within the genomic types B1 (3.1%, 1/32) and A (12.5%, 4/32). Furthermore, AIEC strains were also associated with the genomic groups B2 and D (92.3%, 12/13, p < 0.05), with the exception of AIEC strain CD9-a, which was associated with genomic group A. A significantly lower number of strains was isolated from group A in AIEC compared to non-AIEC strains (p < 0.05). On the other hand, isolates from non-CD patients were similarly distributed among these four main genomic types (38.8%, 7/18 in A; 22.2%, 4/18 in B1; 22.2%, 4/18 in B2; and 16.6%, 3/18 in D).

Occurrence of virulence factors

Similarly, the distribution of virulence factors was diverse among the 32 CD strains studied. fhuD was present in all strains, including non-CD and reference strains, while cdtB was absent in all strains. fimH was present in almost all CD (96.8%, 31/32) and non-CD strains (83.3%, 15/18) studied. The most frequently detected factors were those coding for proteins associated with iron uptake, such as fhuD (32/32), irp2 (25/32), and chuA (27/32). These factors were significantly more common in CD strains (69%) than in non-CD strains 33%) (OR: 4.4, 95% CI, p < 0.05; Table 4). Moreover, the most significant individual biomarker of CD strains was chuA (OR=8.5, 95% CI, p < 0.001). These results demonstrate that the presence of 3 iron transporters, and in particular chuA, is significantly associated with CD strains (Table 4). Furthermore, chuA is significantly associated with AIEC strains compared to non-AIEC strains (OR: 8.2, 95% CI, 0.95–69.74, p < 0.05). Nevertheless, in the case of adhesins, there was no observed association with CD. The adhesin gene fimAv was found to be negatively associated with CD (OR: 0.2, 95%CI: 0.04–0.96, p < 0.05). Toxin analysis showed that the most frequent toxin gene detected was ratA, which was present in 31.2% (10/32) of strains, and also allowed discrimination between CD strains (OR:7.7, 95%CI: 0.89–66.39, p-value > 0.05). The other toxin genes were rare in CD strains (Table 3), as were cdtB (0/32) and cnfI (1/32). The frequency of other virulence factors was as follows: ibeA: 9.3% (3/32), gipA: 12.5% (4/32), pduC; 50% (16/32), and neuC: 34% (11/32). pduC (propanediol catabolism) occurred in approximately 50% of the CD strains and was not significantly associated with CD (OR:2.6; 95%CI: 0.75–9.00, p > 0.1).

Table 4.

Escherichia coli virulence genes in strains isolated from CD and non-CD and their association with Crohn's.

| Virulence factors | Odds Ratio (OR) | P-value | CD Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADHESINS | |||

| fimH | 6.2 (0.59–64.72) | 0.127 | NS |

| fimAv | 0.2 (0.04–0.96) | 0.043* | Negative association |

| aufA | 0.6 (0.15–2.33) | 0.345 | NS |

| papC | 0.6 (0.15–2.33) | 0.345 | NS |

| sfa/focDE | – | – | – |

| afaBC | 0.1 (0.0115–1.1043) | 0.050 | NS |

| IRON TRANSPORTERS | |||

| fhuD | – | – | – |

| chuA | 8.5 (2.21–32.56) | 0.001** | Positive association |

| irp2 | 2.3 (0.64–8.05) | 0.168 | NS |

| three transporters fhuD, chuA, irp2 | 4.4 (1.28–15.09) | 0.016* | Positive association |

| TOXINS | |||

| ratA | 7.7 (0.89–66.39) | 0.034* | Positive association |

| cvaC | 0.9 (0.23–3.19) | 0.541 | NS |

| hlyA | 0.5 (0.06–4.15) | 0.456 | NS |

| cnfl | – | – | – |

| cdtB | – | – | – |

| OTHER VIRULENCE FACTORS | |||

| pduC | 2.6 (0.75–9.00) | 0.108 | NS |

| neuC | 0.6 (0.20–2.13) | 0.342 | NS |

| gipA | 0.5 (0.10–2.30) | 0.303 | NS |

| ibeA | 0.8 (0.1–5.48) | 0.599 | NS |

| SPATEs | |||

| CL-1 | 0.9 (0.28–2.89) | 0.552 | NS |

| CL-2 | 2.0 (0.58–7.02) | 0.209 | NS |

Association between virulence factors and CD. Odds ratio measures how much the affected/non-affected rate increases with the factor. P-values, computed by Fisher Exact Probability Test (one-tailed), give the statistical significance of such effects. Last column indicates association S, Significant (significant (<0.05*); very significant (<0.01)**); NS, Non Significant for null (non-significant) association. Notation:– for not a number.

At least one class-1 or class-2 SPATE gene was found in 66% (21/32) of the CD strains and genes from both classes of SPATEs were present in 31% (10/32) of CD strains (Table 3). In AIEC strains this prevalence was 76% (10/13) and 38% (5/13), respectively. Class-1 SPATE genes were detected in 53% (17/32) of CD strains and class-2 SPATEs were detected in 44% (14/32) of CD strains. 62% (8/13) of AIEC strains contained class-1 SPATEs and 54% (7/13) contained class-2 SPATES. The presence of class-1 and class-2 SPATE genes was not significantly associated with CD or AIEC strains. On the other hand, 61%, (11/18) of non-CD strains harbored genes encoding at least one, class-1 or class-2 SPATEs, and 22% (4/18) more than one class of SPATE. The prevalence of SPATEs genes in non-CD strains was 55% (10/18) for class-1 and 28% (5/18) for class-2. With respect to the association between SPATE classes and the most frequent genomic types found in CD strains (B2 and D), no significant differences were detected in the presence of class-1 SPATEs in B2 (67%, 8/12) or D (53%, 8/15). However, significant differences were observed in the presence of class-2 SPATES between genomic types B2 (75%, 9/12) and D (33%, 5/15). The neuC and Class-2 SPATEs showed different results between Spanish and Chilean CD strains (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Genetic variations in FimH

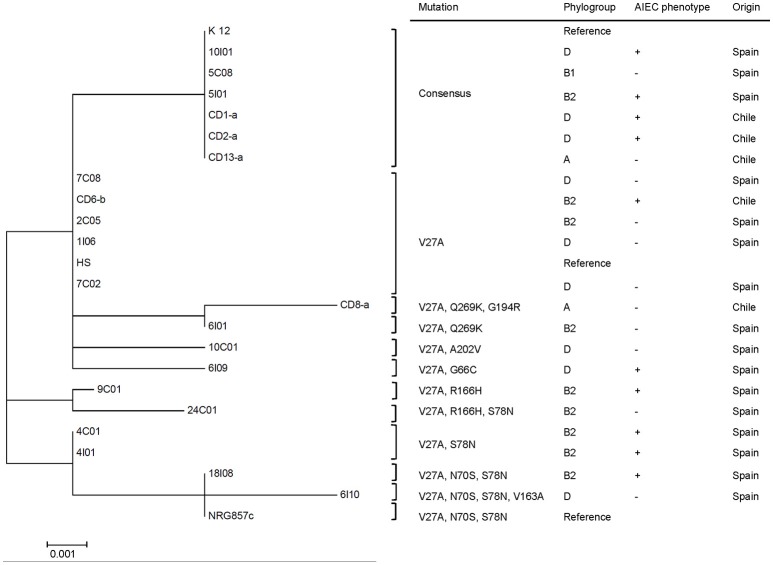

Phylogenetic reconstruction of FimH, from 21 randomly selected CD E. coli isolates, indicated the presence of three major clades (Figure 2). Six out of 21 E. coli strains isolated from CD patients (5C08, 5I01, 10I01, CD1-a, CD2-a, and CD13-a) exhibited a FimH translated sequence identical to that of E. coli K12, whereas the remaining 15 showed the hot-spot mutation V27A. In this case, 9 amino-acid positions were affected by mutations (V27A, G66C, N70S, S78N, V163A, R166H, G194R, A202V, and Q269K) and generated 10 different allelic variants (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A phylogenetic tree based on FimH amino acid sequences of E. coli strains isolated from patients with CD. This tree was constructed using 21 complete FimH sequences from E. coli isolates, the AIEC reference strain NRG857c, E. coli commensal HS, and E. coli K-12 (FimH consensus sequence from reference strain K12), using the nearest-neighbor joining method. The phylogenetic tree presents three main clades and shows 10 different allelic variants.

Altogether, the results indicate that the E. coli strains obtained from CD patients from Chile and Spain were genetically different in nature and did not group according to their geographic origin. In both, Chile and Spain groups of strains, the prevalence of genes associated with iron uptake was high. Some of these strains harbored FimH variants, which is in agreement with previous studies (Iebba et al., 2012). In addition, we found at least one SPATE class was found in 65.6% of E. coli strains isolated from CD patients.

Discussion

E. coli strains, and in particular, the AIEC pathotype, have been identified by many authors as potentially implicated in the pathogenesis of CD (Darfeuille-Michaud et al., 1998; Boudeau et al., 1999; Glasser et al., 2001). The ability to adhere and invade epithelial cells, and survive intracellularly in macrophages characterizes this group of strains (Darfeuille-Michaud et al., 1998; Boudeau et al., 1999; Glasser et al., 2001; De la Fuente et al., 2014). Several virulence factors have been associated with these pathogenic properties in this pathotype (Conte et al., 2014; O'Brien et al., 2016) however they are not exclusive to AIEC strains (Martinez-Medina and Garcia-Gil, 2014). Interestingly, production of type 1 fimbriae appears to correlate with adhesiveness of AIEC strains and certain FimH variants confer them a higher adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells (Dreux et al., 2013). In addition, mucosa-associated E. coli strains isolated from CD patients were very heterogeneous and the most of them belonged to B2 and D genomic types, according to previous investigations (Kotlowski et al., 2007; Martinez-Medina et al., 2009). The E. coli strains isolated from CD were significantly distributed among phylogenetic groups D (p = 0.031), A (p = 0.037), and B1 (p = 0.050) (Table 3) when compared to non-CD strains. The phylogenetic group B2 was not significantly associated with any of the bacterial populations. The most common phylogenetic group among CD isolates was group D (47%) followed by groups B2 (37%), A (12.5%), and B1 (3.5%). Chilean and Spanish CD isolates were not significantly associated particularly with phylogenetic groups B2 (p = 0.058) or D (p = 0.369). In contrast, non-CD isolates were distributed among the following phylogenetic groups: A (36%), B1 (27%), and B2 and D, (18%). These results show significant differences among isolates of virulent strains associated with phylogenetic groups D and B2 from CD vs. non-CD (Table 3). These results are similar to those reported by Nowrouzian et al. (2006). It is possible that CD and non-CD subjects are transiently colonized by E. coli strains with different degrees virulence. However, it appears that those belonging the phylogenetic groups D and B2 are the most able of colonize and survive inside epithelial cells and macrophages in CD patients, particularly those harboring the chuA gene.

To date, all the features mentioned above have been studied in E. coli strains obtained from a particular geographic region. In this work however, we sought to investigate potential differences in mucosa-associated E. coli strains isolated from Chilean and Spanish patients with CD. To this end, we studied the genetic heterogeneity of these two E. coli populations, the presence of virulence factors known to be associated with CD E. coli and the occurrence of class-1 and class-2 SPATEs in these strains.

The clonal analyses of AIEC strains obtained from CD patients through PFGE showed a high degree of genetic variability, which is in agreement with the high variability of the distribution of virulence factors, and is similar to previous publications (Martinez-Medina et al., 2009; De la Fuente et al., 2014; O'Brien et al., 2016). The B2 and D genomic groups were highly prevalent among strains from CD subjects, as has been shown in previous reports (Kotlowski et al., 2007; Martinez-Medina et al., 2009; De la Fuente et al., 2014). Remarkably, we found that strains from different countries did not group according to their origin.

The most distinctive feature of the AIEC strains studied was that all of them had virulence genes related to iron uptake (fhuD, chuA, and irp2), which is in agreement with previous reports demonstrating AIEC strain enrichment with siderophores (Dogan et al., 2014). If a strain harbored the fhuD, chuA, and irp2 transporters together, a high association with CD was noted (Table 4). The iron transporter gene chuA alone was also highly associated with CD (OR: 8.5, p = 0.001), as was the presence of the toxin gene ratA (OR: 7.7, p = 0.034).

The fhuD gene is common among pathogenic and non-pathogenic E. coli strains; however, chuA and irp2 are less common among diarrheagenic and commensal E. coli strains. Nevertheless, both of these genes are present in ExPEC strains. The high prevalence of fhuD, chuA, and irp2, and its significance suggests that these three iron transporters or the presence of chuA alone may act as predictors of CD strains and AIEC isolated patients with CD. They may be relevant biological or diagnostic markers, which could be used to characterize and identify invasive strains isolated from CD patients. Another prevalent gene in the strains studied was pduC, which encodes proteins required for propanediol catabolism, was present in 50% of CD strains and in 66% of AIEC strains. pduC has been also described previously in the S. enterica serovar Thyphimurium (Bobik et al., 1997). The prevalence of pduC in AIEC strains in this study was similar to that reported by Dogan et al. who suggested that its presence in AIEC strains seems to be related to their persistence in macrophage cells (Dogan et al., 2014). However, pduC was not significantly associated with CD strains. The neuC gene is necessary for sialic acid synthesis, which is a carbohydrate monomer component of the K1 capsule, and is a virulence factor that is essential in E. coli strains causing meningitis in newborns (Vann et al., 2004). In addition, the K capsule contributes to intracellular replication of uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strains (Goller and Seed, 2010). neuC was present in 31% of CD strains and it is possible that NeuC plays a similar role in AIEC strains, contributing to its intracellular survival.

In agreement with previous studies, the gene encoding the FimH adhesin of type 1 fimbriae was present in almost all E. coli strains (De la Fuente et al., 2014). In AIEC strains this adhesin is considered a virulence factor and is responsible for mannose-dependent bacterial adherence and invasion of epithelial cells (Barnich et al., 2007; Brument et al., 2013; Dreux et al., 2013). FimH mediates the adhesion of AIEC strains to the apical surface of the ileal epithelium, specifically to the CEACAM6 protein, which is overexpressed in patients with CD (Barnich et al., 2007; Carvalho et al., 2009; Barnich and Darfeuille-Michaud, 2010). Different fimH allelic types occur in AIEC strains, which may increase adhesion to T84 cells and confer colonization advantages in the intestinal tract (Iebba et al., 2012; Dreux et al., 2013). Moreover, allelic replacement of the fimH gene in the AIEC LF82 genetic background by fimH from non-pathogenic K12 strains, significantly reduced bacterial colonization and colitis signs in CEABAC10 transgenic mice expressing human CEACAM6 (Dreux et al., 2013). Some of the mutations reported here, such as V27A, N70S, and S78N, have been previously reported in UPEC strains. These polymorphisms are considered to be potential patho-adaptations that may confer significant advantages in regards to bacterial epithelial colonization (Eris et al., 2016). Such patho-adaptative polymorphisms were also observed in E. coli strains obtained from pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Iebba et al., 2012). V27A and G66C mutations in FimH were associated with CD, and G66S, N70S, and S78N were more prevalent in the B2 and D genomic groups (Iebba et al., 2012). However, Dreux et al. suggested that the V27A polymorphism was not associated with the AIEC pathotype (Dreux et al., 2013). The V27A mutation found in strains isolated from patients with IBD and CD was present in the isolates analyzed here. In our study, we confirmed the presence of several previously described mutations in AIEC strains (V27A, G66C, N70S, S78N, V163A, R166H, G194R, A202V, and Q269K) (Iebba et al., 2012; Dreux et al., 2013). However, the prevalence of V27A in the FimH gene in mucosa-associated E. coli isolated from Chilean and Spanish patients was 71%. Furthermore, the highly invasive AIEC strains, CD2-a and CD1-a (De la Fuente et al., 2014), lack any of the previously reported patho-adaptative polymorphisms. It is likely that adhesion and invasion mechanisms associated with these strains are mediated by other adhesins. Our results are consistent with previous report by Desilets et al. (2016), who suggested that there is no strict association between the previously described polymorphisms of FimH in the AIEC pathotype and its superior adhesion and invasion ability (Desilets et al., 2016).

The prevalence of SPATE genes in mucosa-associated E. coli isolates was also analyzed. SPATE function is varied, they can have intracellular or extracellular protein substrates, and are involved in numerous biological functions, such as those implicated in cytoskeleton stability, autophagy or innate and adaptive immunity (Ruiz-Perez and Nataro, 2014). These proteins have evolved distinct functions that are adaptive to the particular niche occupied by the pathogen (Henderson and Nataro, 2001). We found that 65% of the CD and 73% of AIEC strain isolates presented at least one SPATE gene class. This prevalence is high, but not significantly higher than in the control group (61.1%). These results are similar to those reported by Souza et al., who did not find a significant difference in the presence of SPATEs between CD and control samples (De Souza et al., 2012).

Class-1 SPATE genes were present in 53.1% of CD strains. To date, there are no reports that associate the presence of class-1 SPATEs with CD. Yet, the cytotoxic activity and cellular damage associated with these proteins may promote the intestinal inflammation characteristic of CD. In this context, cytotoxic SPATEs have been found almost exclusively in microbial pathogens (Shigella, enteroagregative E. coli and enteroinvasive E. coli) that induce mucosal damage and inflammation (Boisen et al., 2009). Class-2 SPATE genes were present in 43% of CD isolates and 61.5% of AIEC strains. For most of the proteins of this class, little is known about their possible role in pathogenesis. However, most of the class-2 SPATEs studied to date display proteolytic activity on mucins (Ruiz-Perez and Nataro, 2014), which facilitates the interactions of the bacteria with the intestinal mucosa. Recently, these proteins have been reported to harbor lectin-like properties, conferring the capability of agglutination and adhesion to diverse white cells, as well as the ability to modulate the immune response at distinct levels, cleaving chemokines, complement proteins, adhesion proteins, and co-stimulatory molecules, all involved in malignancy and inflammatory processes (Ayala-Lujan et al., 2014), which may contribute to AIEC pathogenicity.

In conclusion, E. coli strains isolated from CD patients from Spain and Chile show a high degree of genetic variability. They also show significant variability in the virulence genes present, with the exception of genes involved in iron uptake and the ratA toxin gene, which were highly represented in CD strains and are likely to play a relevant role in AIEC pathogenesis. Furthermore, we did not observe an association between the FimH polymorphism and the adhesion and invasion ability of the strains studied. On the other hand, class-1 and -2 SPATE genes were not significantly more prevalent in CD strains or non-CD strains. This study highlights the potential of virulence genes present in CD strains to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of this disease. It is important to highlight that of all of the E. coli strains isolated from patients with CD, both in Chile and Spain, 40% (13/32) were identified as AIEC strains, whose classical characteristics are adhesion to and invasion of cells in culture and resistance to phagocytosis by macrophages.

Author contributions

SC and WS, Study design, experimental analysis, and manuscript writing. FDC, Bioinformatics analysis. MDF, Isolation of Chilean AIEC strains from biopsies. RQ, Collection of biopsies from Chilean patients. MH, Study design and manuscript writing. RM, Isolation of Spanish AIEC strains from biopsies. DG and SK, Collection of biopsies from Spanish patients. JG, Data analysis and English edition. RA, Statistic analysis. RR, Bioinformatics analysis and protocol planning in Spain. RV, Study design and supervision, team coordination among Chile, and Spain, analysis of results, manuscript writing and edition.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was supported by Fondo Nacional De Desarrollo Científico y Tecnológico FONDECYT Postdoctorado 3140468 (SC) & FONDECYT Regular 1161161 (RV).

References

- Arné P., Marc D., Brée A., Schouler C., Dho-Moulin M. (2000). Increased tracheal colonization in chickens without impairing pathogenic properties of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli MT78 with a fimH deletion. Avian Dis. 44, 343–355. 10.2307/1592549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Lujan J. L., Vijayakumar V., Gong M., Smith R., Santiago A. E., Ruiz-Perez F. (2014). Broad spectrum activity of a lectin-like bacterial serine protease family on human leukocytes. PLoS ONE 9:e107920. 10.1371/journal.pone.0107920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnich N., Carvalho F. A., Glasser A. L., Darcha C., Jantscheff P., Allez M., et al. (2007). CEACAM6 acts as a receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli supporting ileal mucosa colonization in Crohn disease. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1566–1574. 10.1172/JCI30504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnich N., Darfeuille-Michaud A. (2010). Abnormal CEACAM6 expression in Crohn disease patients favors gut colonization and inflammation by adherent-invasive E. coli. Virulence 1, 281–282. 10.4161/viru.1.4.11510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobik T. A., Xu Y., Jeter R. M., Otto K. E., Roth J. R. (1997). Propanediol utilization genes (pdu) of Salmonella typhimurium: three genes for the propanediol dehydratase. J. Bacteriol. 179, 6633–6639. 10.1128/jb.179.21.6633-6639.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisen N., Ruiz-Perez F., Scheutz F., Krogfelt K. A., Nataro J. P. (2009). Short report: high prevalence of serine protease autotransporter cytotoxins among strains of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80, 294–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudeau J., Glasser A. L., Masseret E., Joly B., Darfeuille-Michaud A. (1999). Invasive ability of an Escherichia coli strain isolated from the ileal mucosa of a patient with Crohn's disease. Infect. Immun. 67, 4499–4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brument S., Sivignon A., Dumych T. I., Moreau N., Roos G., Guerardel Y., et al. (2013). Thiazolylaminomannosides as potent antiadhesives of type 1 piliated Escherichia coli isolated from Crohn's disease patients. J. Med. Chem. 11, 5395–5406. 10.1021/jm400723n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho F. A., Barnich N., Sivignon A., Darcha C., Chan C. H., Stanners C. P., et al. (2009). Crohn's disease adherent-invasive Escherichia coli colonize and induce strong gut inflammation in transgenic mice expressing human CEACAM. J. Exp. Med. 28l, 2179–2189. 10.1084/jem.20090741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke D. J., Chaudhuri R. R., Martin H. M., Campbell B. J., Rhodes J. M., Constantinidou C., et al. (2011). Complete genome sequence of the Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli strain HM605. J. Bacteriol. 193, 4540. 10.1128/JB.05374-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont O., Bonacorsi S., Bingen E. (2000). Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 4555–4558. 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4555-4558.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte M. P., Longhi C., Marazzato M., Conte A. L., Aleandri M., Lepanto M. S., et al. (2014). Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) in pediatric Crohn's disease patients: phenotypic and genetic pathogenic features. BMC Res. Notes 7:748. 10.1186/1756-0500-7-748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darfeuille-Michaud A., Boudeau J., Bulois P., Neut C., Glasser A. L., Barnich N., et al. (2004). High prevalence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli associated with ileal mucosa in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 127, 412–421. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darfeuille-Michaud A., Neut C., Barnich N., Lederman E., Di Martino P., Desreumaux P., et al. (1998). Presence of adherent Escherichia coli strains in ileal mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 115, 1405–1413. 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente M., Franchi L., Araya D., Díaz-Jiménez D., Olivares M., Álvarez-Lobos M., et al. (2014). Escherichia coli isolates from inflammatory bowel diseases patients survive in macrophages and activate NLRP3 inflammasome. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 304, 384–392. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desilets M., Deng X., Rao C., Ensminger A. W., Krause D. O., Sherman P. M., et al. (2016). Genome-based definition of an inflammatory bowel disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli pathovar. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 1–12. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza H., De Carvalho V., Romeiro F. G., Yukie L., Keller R., Rodrigues J. (2012). Mucosa-associated but not luminal Escherichia coli is augmented in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gut Pathog. 4:21. 10.1186/1757-4749-4-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan B., Suzuki H., Herlekar D., Sartor R. B., Campbell B. J., Roberts C. L., et al. (2014). Inflammation-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli are enriched in pathways for use of propanediol and iron and M-cell translocation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 20, 1919–1932. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreux N., Denizot J., Martinez-Medina M., Mellmann A., Billig M., Kisiela D., et al. (2013). Point mutations in FimH adhesin of Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli enhance intestinal inflammatory response. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003141. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPont H. L., Formal S. B., Hornick R. B., Snyder M. J., Libonati J. P., Sheahan D. G., et al. (1971). Pathogenesis of Escherichia coli diarrhea. N. Eng. J. Med. 285, 1–9. 10.1056/NEJM197107012850101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta P. R., Cappello R., Navarro-García F., Nataro J. P. (2002). Functional comparison of serine protease autotransporters of enterobacteriaceae. Infect. Immun. 70, 7105–7113. 10.1128/IAI.70.12.7105-7113.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eris D., Preston R. C., Scharenberg M., Hulliger F., Abgottspon D., Pang L., et al. (2016). The conformational variability of fimh: which conformation represents the therapeutic target? Chembiochem 17, 1012–1020. 10.1002/cbic.201600066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibold L., Garenaux E., Dalmasso G., Gallucci C., Cia D., Mottet-Auselo B., et al. (2016). The Vat-AIEC protease promotes crossing of the intestinal mucus layer by Crohn's disease-associated Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 617–631. 10.1111/cmi.12539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser A. L., Boudeau J., Barnich N., Perruchot M. H., Colombel J. F., Darfeuille-Michaud A. (2001). Adherent invasive Escherichia coli strains from patients with Crohn's disease survive and replicate within macrophages without inducing host cell death. Infect. Immun. 69, 5529–5537. 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5529-5537.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goller C. C., Seed P. C. (2010). High-throughput identification of chemical inhibitors of E. coli Group 2 capsule biogenesis as anti-virulence agents. PLoS ONE 5:e11642. 10.1371/journal.pone.0011642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson I. R., Nataro J. P. (2001). Virulence functions of autotransporter proteins. Infect. Immun. 69, 1231–1243. 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1231-1243.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iebba V., Conte M. P., Lepanto M. S., Di Nardo G., Santangelo F., Aloi M., et al. (2012). Microevolution in fimH gene of mucosa-associated Escherichia coli strains isolated from pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Infect. Immun. 80, 1408–1417. 10.1128/IAI.06181-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J. R., Stell A. L. (2000). Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181, 261–272. 10.1086/315217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser A., Zeissig S., Blumberg R. S. (2010). Genes and environment: how will our concepts on the pathophysiology of IBD develop in the future? Dig. Dis. 28, 395–405. 10.1159/000320393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotlowski R., Bernstein C. N., Sepehri S., Krause D. O. (2007). High prevalence of Escherichia coli belonging to the B2+D phylogenetic group in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 56, 669–675. 10.1136/gut.2006.099796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bouguenec C., Archambaud M., Labigne A. (1992). Rapid and specific detection of the pap, afa, and sfa adhesin-encoding operons in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30, 1189–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. M., Bergquist E. J., Nalin D. R., Waterman D. H., Hornick R. B., Young C. R., et al. (1978). Escherichia coli strains that cause diarrhoea but do not produce heat-labile or heat-stable enterotoxins and are non-invasive. Lancet 1, 1119–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc D., Dho-Moulin M. (1996). Analysis of the fim cluster of an avian O2 strain of Escherichia coli: serogroup-specific sites within fimA and nucleotide sequence of fimI. J. Med. Microbiol. 44, 444–452. 10.1099/00222615-44-6-444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Medina M., Garcia-Gil L. J. (2014). Escherichia coli in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases: an update on adherent invasive Escherichia coli pathogenicity. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 5, 213–227. 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Medina M., Mora A., Blanco M., López C., Alonso M. P., Bonacorsi S., et al. (2009). Similarity and divergence among adherent-invasive Escherichia coli and extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 3968–3979. 10.1128/JCM.01484-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash J. H., Villegas A., Kropinski A. M., Aguilar-Valenzuela R., Konczy P., Mascarenhas M., et al. (2010). Genome sequence of adherent-invasive Escherichia coli and comparative genomic analysis with other E. coli pathotypes. BMC Genomics 11:667. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowrouzian F. L., Adlerberth I., Wold A. E. (2006). Enhanced persistence in the colonic microbiota of Escherichia coli strains belonging to phylogenetic group B2: role of virulence factors and adherence to colonic cells. Microbes Infect. 8, 834–840. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien C. L., Bringer M. A., Holt K. E., Gordon D. M., Dubois A. L., Barnich N., et al. (2016). Comparative genomics of Crohn's disease-associated adherent-invasive Escherichia coli. Gut 1–8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Perez F., Nataro J. P. (2014). Bacterial serine proteases secreted by the autotransporter pathway: classification, specificity, and role in virulence. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 745–770. 10.1007/s00018-013-1355-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P., Kelly R. G., Lee G., Collins J. K., O'Sullivan G. C., O'Connell J., et al. (2004). Bacterial DNA within granulomas of patients with Crohn's disease–detection by laser capture microdissection and PCR. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 99, 1539–1543. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultsz C., Van Den Berg F. M., Ten Kate F. W., Tytgat G. N., Dankert J. (1999). The intestinal mucus layer from patients with inflammatory bowel disease harbors high numbers of bacteria compared with controls. Gastroenterology 117, 1089–1097. 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70393-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokurenko E. V., Chesnokova V., Doyle R. J., Hasty D. L. (1997). Diversity of the Escherichia coli type 1 fimbrial lectin. Differential binding to mannosides and uroepithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17880–17886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vann W. F., Daines D. A., Murkin A. S., Tanner M. E., Chaffin D. O., Rubens C. E., et al. (2004). The NeuC protein of Escherichia coli K1 is a UDP N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase. J. Bacteriol. 186, 706–712. 10.1128/JB.186.3.706-712.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal R., Ginard D., Khorrami S., Mora-Ruiz M., Munoz R., Hermoso M., et al. (2015). Crohn associated microbial communities associated to colonic mucosal biopsies in patients of the western Mediterranean. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 38, 442–452. 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt S., Lanotte P., Mereghetti L., Moulin-Schouleur M., Picard B., Quentin R. (2003). Escherichia coli strains from pregnant women and neonates: intraspecies genetic distribution and prevalence of virulence factors. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 1929–1935. 10.1128/JCM.41.5.1929-1935.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto S., Terai A., Yuri K., Kurazono H., Takeda Y., Yoshida O. (1995). Detection of urovirulence factors in Escherichia coli by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 12, 85–90. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen Y. T., Kostakioti M., Henderson I. R., Stathopoulos C. (2008). Common themes and variations in serine protease autotransporters. Trends Microbiol. 16, 370–379. 10.1016/j.tim.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]