Abstract

Measurement of disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is important for monitoring disease progression and evaluating the therapeutic effects. The severity of organ damage correlates with clinical status and prognosis. Therefore, it is imperative to find an effective biomarker measuring disease activity and organ damage for SLE management. The present study investigated the possibility of serum calreticulin (CRT) in the assessment of disease activity and organ damage in SLE patients. Serum CRT levels from 80 patients with SLE, 55 patients with other autoimmune diseases and 60 healthy controls (HC) were measured by ELISA. Disease activity was assessed using the Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) scores. Organ damage was evaluated with the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index. CRT levels in SLE were significantly higher than that in other autoimmune diseases and HC. CRT was correlated with SLEDAI-2K score (r=0.3345, P=0.0024), and with anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) (r=0.4483, P<0.0001). A significant negative correlation of CRT levels with complement 3 (r=−0.3635, P=0.0009) and complement 4 (r=−0.3507, P=0.0014) was observed in patients with SLE. Furthermore, the patients with SLE and a positive anti-Ro52 result had higher levels of CRT compared with those with a negative anti-Ro52 result (P<0.001). Elevated levels of CRT were also reported among patients with SLE who also indicated the presence of cumulative organ damage. In addition, increased expression of CRT correlated with the presence of lupus nephritis. In conclusion, the results of the current report provided that CRT may be used as a potential biomarker for clinical diagnosis and of prognosis, providing additional information regarding disease activity and organ damage alongside other traditional indices.

Keywords: calreticulin, systemic lupus erythematosus, disease activity, SLEDAI-2K score

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic complex multisystem autoimmune disease that is characterized by the production of diverse autoantibodies (1,2). The loss of immune tolerance to self-antigens results in the activation of the immune system to produce autoantibodies, which leads to clinical manifestations including lupus nephritis (LN), nondestructive arthritis, cutaneous rash, vasculitis, central nervous system and cardiopulmonary symptoms (3). The selection of an intensive treatment strategy for clinical remission of SLE is based on the assessment of the disease activity; therefore, measurement of disease activity has become an essential step in monitoring disease progression and assessing therapeutic effects (4).

Calreticulin (CRT) is a 46 kDa Ca2+ binding chaperone that has multiple functions both inside and outside of the endoplasmic reticulum, including Ca2+ homeostasis and glycoprotein folding (5). Previous studies have revealed that CRT is implicated in a number of autoimmune processes, such as molecular mimicry, epitope spreading, complement inactivation, and stimulation of inflammatory mediators (6–9). These findings suggest that CRT not only acts as an autoantigen, but also serves an active role in the pathological processes of various autoimmune diseases (5,10). Previous findings, showed an elevation of CRT concentration in the serum of patients with SLE and its relation to this autoimmune disorder (11–13). However, to the best of our knowledge, the association of CRT with disease activity and organ damage has not been reported.

The present study evaluates the levels of serum CRT in patients with SLE and its correlation to SLE disease activity and organ damage. Currently, the systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score is widely utilised to assess disease activity in SLE patients (14,15). The current study investigated the association of serum CRT with SLEDAI-2K scores, and other conventional markers of SLE disease activity, including complement 3 (C3), complement 4 (C4) and anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA). Besides those markers, the correlation between serum CRT levels and anti-Ro52 was also analyzed in the patients with SLE, based on a previous study by Kvarnstrom et al (16) reporting that anti-Ro52 is significantly associated with disease activity in patients with SLE. In addition, correlation between the level of CRT and organ damage (defined as chronic, nonreversible change, not associated with active inflammation, occurring since the onset of lupus and present for at least 6 months) were also investigated in the present study. Organ damage was evaluated in this investigation using Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (SDI), which is a widely accepted tool to measure organ damage and regarded as the gold standard for this kind of assessment (17).

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

Serum samples of patients were obtained from 80 patients with SLE, 55 patients with other autoimmune disease (16 Sjögren's syndrome, 19 ankylosing spondylitis, 20 systemic scleroderma) and 60 age and gender-matched healthy control subjects (HC) (Table I). All patients with SLE fulfilled the American College of Rheumatology 1997 criteria for SLE (18). Patients with other diseases fulfilled their corresponding diagnostic criteria (19–21). The control group comprised healthy volunteers with no history of autoimmune disease or immunosuppressive therapy. Tianjin Medical University (Tianjin, China) provided ethical approval for all experiments. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the control subjects.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the study populations.

| Characteristic | SLE (n=80) | Other autoimmune diseases (n=55) | Healthy control (n=60) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 35±12 | 40±14 | 38±14 |

| Gender, n | |||

| Female | 71 | 42 | 41 |

| Male | 9 | 13 | 19 |

| Disease duration, years | 4.52±3.81 | 4.83±3.68 | – |

| Anti-dsDNA, IU/ml | 309.69±238.47 | – | – |

| C3, mg/dl | 82.7±37.8 | – | – |

| C4, mg/dl | 16.3±6.80 | – | – |

| SLEDAI-2K | 10.81±5.02 | – | – |

| SDI | 0.82±1.12 | – | – |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. SLE, Systemic lupus erythematosus; anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA; C3, complement 3; C4, complement 4; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; Disease Activity Index 2000 score; SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index.

Sample preparation

All serum samples were centrifuged at 1,800 × g for 10 min, immediately aliquoted and stored at −80°C. All samples were only allowed to thaw once.

Determination of CRT levels in serum samples by ELISA

The concentration of CRT in serum was measured by sandwich ELISA (catalogue no. xl-Em1860; Xinle Biology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Optical density values of each well were assessed using an ELISA plate reader (Multiskan MK3; Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 450 nm.

CRT expression in serum by western blot analysis

All serum samples were diluted and denatured for 5 min at 95°C following addition of loading buffer. The serum proteins (20 µg in total) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequently were transferred to the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane for 1 h at a constant current of 250 mA. The membrane was blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% skim milk/TBST (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated with rabbit anti-human CRT polyclonal antibody (PA3-900; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and rabbit anti-human serum albumin antibody (ab83465; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), which served as a control, for 1 h at room temperature (dilution, 1:2,500 in 5% skim milk/TBST). After washing for 30 min with TBST three times, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Bioworld, Irving, TX, USA) for 1 h at room temperature (dilution, 1:1,000 in 5% skim milk/TBST). Following washing, proteins were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Solarbio Bioscience and Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). These data were then analyzed using ImageJ 1.43 software. CRT expression was normalized against albumin expression.

Clinical and laboratory measurements

Serum samples were collected from each patient with SLE, routine hematological tests were performed and serum was separated and used for biochemical tests and immune assays. The following clinical and laboratory data were collected: Age, gender and levels of anti-dsDNA, C3, C4 and anti-Ro52. Anti-dsDNA antibodies were tested by ELISA (catalogue no. ORG 204G; Orgentec Diagnostika GmbH, Mainz, Germany), serum concentrations of complement factors C3 and C4 were determined by immunization rate scattering turbidimetry (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA) (22) and anti-Ro52 was detected by ANA Profile 3 EUROLINE (catalogue no. DL 1590-1601-3G, Oumeng Co., Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among groups were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Student-Newman-Keuls test was used for a comparison between groups. Correlation was determined by Pearson's correlation coefficient. P-value of <0.05 were considered to represent a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the participants

The detailed clinical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table I. There was no significant difference in gender and age amongst the groups (P>0.05).

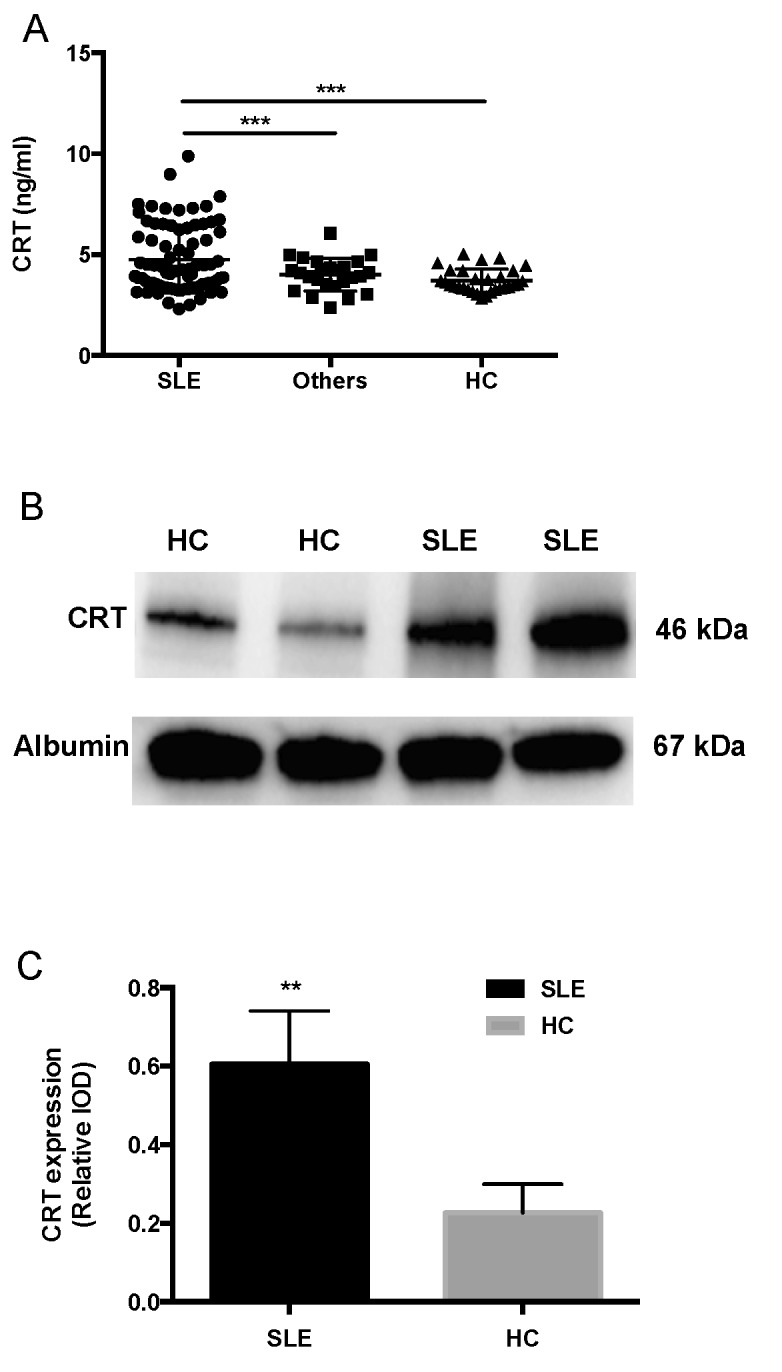

Increased levels of CRT in serum from patients with SLE

Serum CRT levels were measured by ELISA. Data of CRT levels from three groups was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. The difference among these groups was statistically significant (F=7.589; P<0.001). Pairwise comparisons were performed using the Student-Newman-Keuls test, revealing that CRT levels in patients with SLE (4.740±0.646 ng/ml) were significantly higher than those of other autoimmune diseases (4.008±0.815 ng/ml) and HC (3.703±0.582 ng/ml) (P<0.001; Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Increased levels of CRT in the serum of SLE patients. (A) ELISA analysis of serum CRT in patients with SLE and other autoimmune diseases and HC (n=80, 55 and 60, respectively). ***P<0.001 (B) Representative western blot analysis of CRT expression in the serum of patients with SLE and HC. (C) CRT expression relative to albumin in the serum of patients with SLE and HC. **P<0.01. CRT, calreticulin; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; HC, healthy control; IOD, integrated optical density.

Western blotting analysis was used to detect the serum CRT from the serum samples of SLE and HC. CRT levels were increased in SLE patients compared with HC (Fig. 1B). The integrated optical density of SLE (23,764±4.685) was significantly higher than HC (11,532±4,936; P<0.05). The integrated optical density of serum albumin was also analyzed (36,540±18,653). CRT expression relative to albumin in patients with SLE (0.60±0.14) was significantly higher compared with HC (0.23±0.07, P<0.01; Fig. 1C).

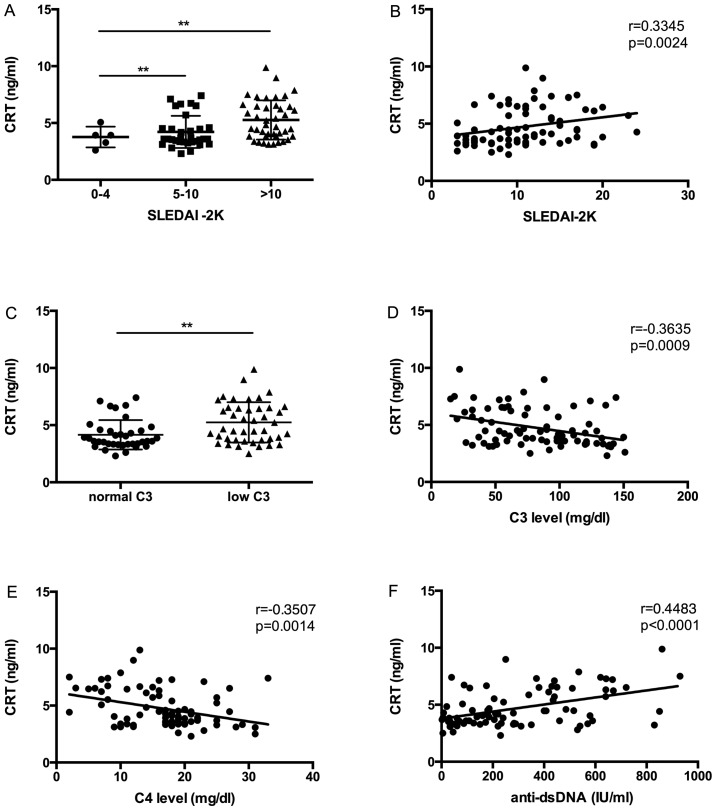

Correlation of serum CRT levels with disease activity in SLE patients

To investigate whether the expression of CRT levels in SLE serum were correlated with disease activity, CRT levels and disease activity indices (SLEDAI-2K, C3, C4, anti-dsDNA) were compared and analyzed by Pearson's correlation coefficient. In accordance with the SLEDAI-2K flare scoring system (23), SLE patients were divided into three groups: i) Patients with stable disease (SLEDAI-2K scores from 0 to 4); ii) patients with a mild flare (SLEDAI-2K scores from 5 to 10); and iii) SLE patients with a moderate to severe disease flare (SLEDAI-2K scores >10). CRT levels were significantly increased in patients with SLE who had a mild flare and a moderate to severe flare of disease than in patients without flare (Fig. 2A). In addition, a significant correlation was observed between CRT levels and SLEDAI-2K scores in SLE patients (r=0.3345, P=0.0024) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Association of CRT expression with disease activity in SLE patients. (A) Correlation of SLE patients with a moderate to severe flare of disease (SLEDAI-2K score >10), a mild flare of disease (SLEDAI-2K score from 5 to 10) and those without a disease flare (SLEDAI-2K score <4) with CRT expression. (B) CRT level correlation with SLEDAI-2K score. (C) CRT expression correlation with low (<90 mg/dl) and normal C3 levels. (D) Correlation between CRT expression and C3 levels in patients with SLE. (E) Correlation between CRT expression and C4 levels in patients with SLE patients. (F) CRT correlation with anti-dsDNA. **P<0.01. CRT, calreticulin; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000; C3, complement 3; C4, complement 4; Anti-dsDNA, anti-double-stranded DNA.

Complement deficiency is often observed in SLE with active disease, and C3 is therefore another index of disease activity (24,25). In the present study, CRT expression was significantly increased in patients with SLE who had a low level of C3 (<90 mg/dl) compared with those with normal levels of C3 (P<0.05; Fig. 2C). It was additionally revealed that C3 levels were negatively correlated with CRT levels (r=−0.3635, P=0.0009) (Fig. 2D).

Correlation of serum CRT level with other disease activity markers like C4 and anti-dsDNA were also analyzed. A significant negative correlation between CRT level and C4 level was observed (r=−0.3507, P=0.0014) (Fig. 2E), and a significant positive correlation between CRT level and anti-dsDNA level was also demonstrated (r=0.4483, P<0.0001) (Fig. 2F).

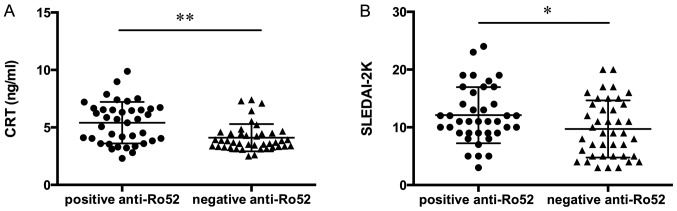

As reported in Fig. 3A, patients with SLE who were positive for anti-Ro52 demonstrated significantly increased levels of CRT compared to patients negative for anti-Ro52. Furthermore, SLE patients with a positive anti-Ro52 result reported significantly higher SLEDAI-2K compared to those patients with a negative anti-Ro52 result (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) CRT levels and (B) SLEDAI-2K scores in SLE patients positive or negative for anti-Ro52. *P<0.05; **P<0.001. CRT, calreticulin; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000.

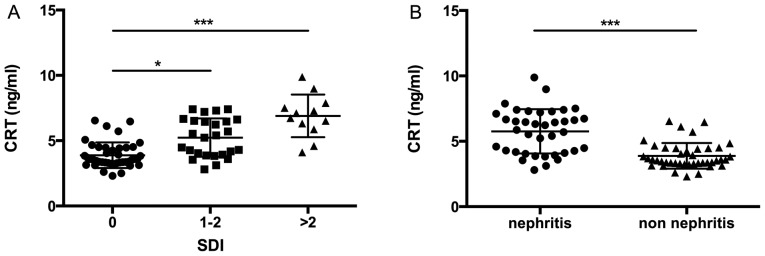

Association between CRT levels in SLE patients and organ damage

SLE is a chronic multisystem autoimmune disease that may lead to morbidity. It has been noted that disease activity, particularly when individual organs are considered, may result in specific organ damage (26,27). The current results revealed that increased CRT level was associated with different levels of organ damage in patients with SLE. It was demonstrated that higher levels of CRT were present in patients with SLE with SDI scores of 1–2 and in those with SDI scores >2 vs. those without organ damage (P<0.05 and P<0.001, respectively; Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

CRT expression in SLE patients with and without organ damage. (A) Correlation of CRT levels with SDI score. (B) Correlation of CRT levels with patients with SLE with and without LN. *P<0.05; ***P<0.001. SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index; LN, lupus nephritis.

LN is one of the most common clinical manifestations of organ damage in SLE. In the present cohort, 47.5% of patients (38 of 80 patients with SLE) had either previous or current LN (Table II). Patients with LN had higher CRT expression level than those without renal manifestations (P<0.001; Fig. 4B).

Table II.

Presence and absence of clinical features of SLE.

| SLE clinical features present | SLE clinical features absent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD | P-value |

| Renal | 38 | 5.62±1.845 | 42 | 4.28 ±1.539 | 0.0009 |

| Rash | 22 | 4.79±1.790 | 58 | 4.82±1.701 | NS |

| Arthritis | 24 | 5.01±1.857 | 56 | 4.92±1.540 | NS |

| Serositis | 10 | 4.83±1.691 | 70 | 4.77±1.752 | NS |

| Mucosal ulcer | 11 | 4.85±1.876 | 69 | 4.79±1.505 | NS |

| Hematological | 19 | 4.89±1.892 | 61 | 4.98±1.597 | NS |

| Neurological | 5 | 4.93±1.654 | 75 | 4.98±1.816 | NS |

SD, standard deviation; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; NS, not significant.

Discussion

The diagnosis of SLE requires a combination of clinical manifestations and biomarkers. The traditional laboratory indices fail to identify the pathogenic processes, organ damage and therapeutic effects. It is therefore necessary to identify more biomarkers to monitor disease progression and assess the effects of treatment of SLE (27). In the present study, the CRT expression level was investigated as a correlative analysis with the degree of SLE activity and organ damage.

Significant epidemiological evidence indicates that elevated serum CRT is associated with various medical conditions, particularly autoimmune diseases (28,29). A previous report noted that serum CRT was associated with the 28-joint count Disease Activity Score and Health Assessment Questionnaire score in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (30). The current results reported that CRT levels were increased in patients with SLE compared with patients with other diseases and HC. These results are consistent with a previous study that described increased serum levels of CRT in SLE patients (13). In the present study, western blotting analysis and ELISA were used to observe the expression of serum CRT; it was illustrated that the formation of CRT that may occur in serum in dimers or oligomers, and other CRT forms were not detected.

In the current study, the elevated serum CRT levels in SLE patients were correlated with SLEDAI-2K scores, which is the most common index assessing the level of disease activity in SLE patients and C3 levels (31). In addition, serum CRT level was correlated with other disease activity markers such as C4 and anti-dsDNA levels. The present investigation also revealed a significant association between CRT and anti-Ro52 levels in the patients with SLE; the patients who were positive for anti-Ro52 had higher levels of CRT. The correlation between serum CRT and notable parameters associated with SLE disease activity indicates that CRT may represent an important potential biomarker of disease monitoring and prognosis. Borba et al (32) previously reported that increased disease activity in patients with SLE was associated with the production of serum cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-6, with higher serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6 correlating with SLEDAI scores (33,34). In previous study, Duo et al (35) reported that soluble CRT induces TNF-α and IL-6 production through mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-κB signaling pathways. The present results also suggested a possible role of CRT in disease activity and pathogenesis of SLE.

The reason for elevated CRT levels in SLE patients is poorly understood. Previous studies reported that antibodies of CRT could be detected in serum of patients with SLE (11,12,36). However, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first report of a notable correlation between CRT and anti-Ro52. A previous study suggested that CRT is a protein member of the Ro/La-RNP complex and is specifically recognized by anti-Ro autoantibody (12). CRT is implicated in the phenomenon of ‘epitope spreading’, in which initiation of immunity to Ro52 induces the production of anti-CRT autoantibodies in a number of strains of mice (37). Anti-Ro52 reactivity is not disease-specific but may be of importance in patients with SLE., and the role of anti-Ro52 in SLE patients may reflect disease activity (16). Anti-Ro52 and CRT are suggested to participate in pathogenesis of SLE (12,38); the significance of CRT and anti-Ro52 in SLE therefore represent the subject of subsequent work.

CRT expression was reported in the present study to be increased in SLE with ongoing or cumulative organ damage, as determined by SDI score and the presence of LN. However, CRT expression did not participate in clinical manifestations other than LN. Although the CRT level in SLE patients with the presence of arthritis is higher than those with the absence of arthritis, there was no significant correlation between these. Observations of the current study indicate CRT as a promising biomarker for monitoring SLE disease progression and a major manifestation in SLE patients.

CRT serves a crucial role in regulating intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (39). Previous studies by Sela-Brown et al (40) and Wheeler et al (41) reported that 1,25-dihydroxyvitaminD3 can be inhibited by CRT in vitro and in vivo. Subsequent study elaborated on the link between serum concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxyvitaminD3 and the development and progression of SLE, finding that 1,25-dihydroxyvitaminD3 serum concentrations were inversely correlated with disease activity and organ damage (42). Low serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitaminD3 is associated with photosensitization, arthritis and kidney damage (43,44). The current study focused on the relationship between serum CRT level and organ damage in SLE patients, suggesting that elevated CRT expression is associated with cumulative organ damage in SLE. However, this was not a functional study of CRT, meaning that the underlying mechanism requires additional investigation.

In conclusion, the present report demonstrates that the elevated serum CRT levels in SLE patients parallel the degree of disease activity and organ damage. These observations provide additional evidence for a possible role of CRT in predicting long-term outcome and prognosis in patients with SLE.

Acknowledgements

The current study was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81601820), Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 15JCQNJC11600 and 15JCYBJC27400) and Tianjin City High School Science & Technology Fund Planning Project (grant no. 20140124).

References

- 1.Liang P, Tang Y, Fu S, Lv J, Liu B, Feng M, Li J, Lai D, Wan X, Xu A. Basophil count, a marker for disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol. 2015;34:891–896. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2822-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dipti TR, Azam MS, Sattar MH, Rahman SA. Detection of anti-nuclear antibody by immunofluorescence assay and enzyme immunoassay in childhood systemic lupus erythematosus: Experience from Bangladesh. Int J Rheum Dis. 2012;15:121–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das UN. Current and emerging strategies for the treatment and management of systemic lupus erythematosus based on molecular signatures of acute and chronic inflammation. J Inflamm Res. 2010;3:143–170. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S9425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devaraju P, Witte T, Schmidt RE, Gulati R, Negi VS. Immunoglobulin-like transcripts 6 (ILT6) polymorphism influences the anti-Ro60/52 autoantibody status in South Indian SLE patients. Lupus. 2014;23:1149–1155. doi: 10.1177/0961203314538107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggleton P, Llewellyn DH. Pathophysiological roles of calreticulin in autoimmune disease. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:466–473. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggleton P, Ward FJ, Johnson S, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR, Hajela VA, Michalak M, Corbett EF, Staines NA, Reid KB. Fine specificity of autoantibodies to calreticulin: Epitope mapping and characterization. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;120:384–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan Q, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Song Y. Structural insight into the role of thrombospondin-1 binding to calreticulin in calreticulin-induced focal adhesion disassembly. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3685–3694. doi: 10.1021/bi902067f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goëb V, Thomas-L'Otellier M, Daveau R, Charlionet R, Fardellone P, Le Loët X, Tron F, Gilbert D, Vittecoq O. Candidate autoantigens identified by mass spectrometry in early rheumatoid arthritis are chaperones and citrullinated glycolytic enzymes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R38. doi: 10.1186/ar2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Almeida DE, Ling S, Holoshitz J. New insights into the functional role of the rheumatoid arthritis shared epitope. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3619–3626. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michalak M, Groenendyk J, Szabo E, Gold LI, Opas M. Calreticulin, a multi-process calcium-buffering chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem J. 2009;417:651–666. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van den Berg RH, Siegert CE, Faber-Krol MC, Huizinga TW, van Es LA, Daha MR. Anti-C1q receptor/calreticulin autoantibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;111:359–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00473.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehm J, Orth T, Van Nguyen P, Söling HD. Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with increased auto-antibody titers against calreticulin and grp94, but calreticulin is not the Ro/SS-A antigen. Eur J Clin Invest. 1994;24:248–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1994.tb01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong C, Qiu X, Li Y, Huang Q, Zhong Z, Zhang Y, Liu X, Sun L, Lv P, Gao XM. Functional analysis of recombinant calreticulin fragment 39–272: Implications for immunobiological activities of calreticulin in health and disease. J Immunol. 2010;185:4561–4569. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan J, Li LI, Wang Z, Song W, Zhang Z. Dyslipidemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Association with disease activity and B-type natriuretic peptide levels. Biomed Rep. 2016;4:68–72. doi: 10.3892/br.2015.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urowitz MB, Isenberg DA, Wallace DJ. Safety and efficacy of hCDR1 (Edratide) in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: Results of phase II study. Lupus Sci Med. 2015;2:e000104. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2015-000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kvarnstrom M, Dzikaite-Ottosson V, Ottosson L, Gustafsson JT, Gunnarsson I, Svenungsson E, Wahren-Herlenius M. Autoantibodies to the functionally active RING-domain of Ro52/SSA are associated with disease activity in patients with lupus. Lupus. 2013;22:477–485. doi: 10.1177/0961203313479420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero-Diaz J, Isenberg D, Ramsey-Goldman R. Measures of adult systemic lupus erythematosus: Updated version of British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG 2004), European Consensus Lupus Activity Measurements (ECLAM), Systemic Lupus Activity Measure, Revised (SLAM-R), Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire for Population Studies (SLAQ), Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K), and Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (SDI) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 1):S37–S46. doi: 10.1002/acr.20572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziegelasch M, van Delft MA, Wallin P, Skogh T, Magro-Checa C, Steup-Beekman GM, Trouw LA, Kastbom A, Sjöwall C. Antibodies against carbamylated proteins and cyclic citrullinated peptides in systemic lupus erythematosus: Results from two well-defined European cohorts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:289. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-1192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imrich R, Alevizos I, Bebris L, Goldstein DS, Holmes CS, Illei GG, Nikolov NP. Predominant glandular cholinergic dysautonomia in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1345–1352. doi: 10.1002/art.39044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Liao Q, Hu Y, Zhong D. T lymphocyte subset imbalances in patients contribute to ankylosing spondylitis. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:250–256. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson SR, Fransen J, Khanna D, Baron M, van den Hoogen F, Medsger TA, Jr., Peschken CA, Carreira PE, Riemekasten G, Tyndall A, et al. Validation of potential classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:358–367. doi: 10.1002/acr.20684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu XH, Chen Q, Ke JW, Liu JM, Li L, Li J, He MJ, Hu CL. Clinical analysis of immune function changes in children with bronchial pneumonia. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2013;15:175–178. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munroe ME, Vista ES, Guthridge JM, Thompson LF, Merrill JT, James JA. Pro-inflammatory adaptive cytokines and shed tumor necrosis factor receptors are elevated preceding systemic lupus erythematosus disease flare. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:1888–1899. doi: 10.1002/art.38573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papp K, Végh P, Hóbor R, Szittner Z, Vokó Z, Podani J, Czirják L, Prechl J. Immune complex signatures of patients with active and inactive SLE revealed by multiplex protein binding analysis on antigen microarrays. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brendan M, Boackle SA. Linking complement and anti-dsDNA antibodies in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Res. 2013;55:10–21. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8345-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magro-Checa C, Zirkzee EJ, Huizinga TW, Steup-Beekman GM. Management of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: Current approaches and future perspectives. Drugs. 2016;76:459–483. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0534-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y, Zhang F, Ma J, Zhang X, Wu L, Qu B, Xia S, Chen S, Tang Y, Shen N. Association of large intergenic noncoding RNA expression with disease activity and organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:131. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0632-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelebart P, Opas M, Michalak M. Calreticulin, a Ca2+-binding chaperone of the endoplasmic reticulum. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He MC, Wang J, Wu J, Gong FY, Hong C, Xia Y, Zhang LJ, Bao WR, Gao XM. Immunological activity difference between native calreticulin monomers and oligomers. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ni M, Wei W, Wang Y, Zhang N, Ding H, Shen C, Zheng F. Serum levels of calreticulin in correlation with disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:947–953. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Compagno M, Gullstrand B, Jacobsen S, Eilertsen GØ, Nilsson JÅ, Lood C, Jönsen A, Truedsson L, Sturfelt G, Bengtsson AA. The assessment of serum-mediated phagocytosis of necrotic material by polymorphonuclear leukocytes to diagnose and predict the clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus: An observational longitudinal study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:44. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0941-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borba VZ, Vieira JG, Kasamatsu T, Radominski SC, Sato EI, Lazaretti-Castro M. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:427–433. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy EM, Smith S, Lee RZ, Cunnane G, Doran MF, Donnelly S, Howard D, O'Connell P, Kearns G, Ní Gabhann J, Jefferies CA. The association of cytokines with disease activity and damage scores in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1586–1594. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Umare V, Pradhan V, Nadkar M, Rajadhyaksha A, Patwardhan M, Ghosh KK, Nadkarni AH. Effect of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β) on clinical manifestations in Indian SLE patients. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:385297. doi: 10.1155/2014/385297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duo CC, Gong FY, He XY, Li YM, Wang J, Zhang JP, Gao XM. Soluble calreticulin induces tumor necrosis factor-a (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-6 production by macrophages through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and NFκB signaling pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:2916–2928. doi: 10.3390/ijms15022916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Routsias JG, Tzioufas AG, Sakarellos-Daitsiotis M, Sakarellos C, Moutsopoulos HM. Calreticulin synthetic peptide analogues: Anti-peptide antibodies in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;91:437–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinoshita G, Keech CL, Sontheimer RD, Purcell A, McCluskey J, Gordon TP. Spreading of the immune response from 52 kDaRo and 60 kDaRo to calreticulin in experimental autoimmunity. Lupus. 1998;7:7–11. doi: 10.1191/096120398678919606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menéndez A, Gómez J, Caminal-Montero L, Díaz-López JB, Cabezas-Rodríguez I, Mozo L. Common and specific associations of anti-SSA/Ro60 and anti-Ro52/TRIM21 antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:832789. doi: 10.1155/2013/832789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang WA, Groenendyk J, Michalak M. Calreticulin signaling in health and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:842–846. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sela-Brown A, Russell J, Koszewski NJ, Michalak M, Naveh-Many T, Silver J. Calreticulin inhibits vitamin D's action on the PTH gene in vitro and may prevent vitamin D's effect in vivo in hypocalcemic rats. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1193–1200. doi: 10.1210/me.12.8.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wheeler DG, Horsford J, Michalak M, White JH, Hendy GN. Calreticulin inhibits vitamin D3 signal transduction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3268–3274. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amital H, Szekanecz Z, Szücs G, Dankó K, Nagy E, Csépány T, Kiss E, Rovensky J, Tuchynova A, Kozakova D, et al. Serum concentrations of 25-OH vitamin D in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are inversely related to disease activity: Is it time to routinely supplement patients with SLE with vitamin D? Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1155–1157. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.120329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mandal M, Tripathy R, Panda AK, Pattanaik SS, Dakua S, Pradhan AK, Chakraborty S, Ravindran B, Das BK. Vitamin D levels in Indian systemic lupus erythematosus patients: Association with disease activity index and interferon alpha. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R49. doi: 10.1186/ar4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schoindre Y, Jallouli M, Tanguy ML, Ghillani P, Galicier L, Aumaître O, Francès C, Le Guern V, Lioté F, Smail A, et al. Lower vitamin D levels are associated with higher systemic lupus erythematosus activity, but not predictive of disease flare-up. Lupus Sci Med. 2014;1:e000027. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2014-000027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]