Abstract

Pax2 is a transcription factor that is crucial for kidney development, and it is also expressed in the normal adult kidney, where its physiological function is unknown. In the present study, we find by cDNA microarray analysis that Pax2 expression in second-passage mouse inner-medullary epithelial cells is increased by a high NaCl concentration, which is significant because NaCl levels are normally high in the inner medulla in vivo, and varies with urinary concentration. Furthermore, a high NaCl concentration increases Pax2 mRNA and protein expression in mouse inner medullary collecting duct (mIMCD3) cells, and its transcriptional activity. Pax2 mRNA and protein expression is high in normal adult mouse renal inner medulla but much lower in renal cortex. Pax2 protein is present in collecting duct cells in both renal medulla and cortex and in thin descending limbs of Henle's loop in inner medulla. Treating Brattleboro rats with desamino-Cys-1,d-Arg-8 vasopressin, which increases inner-medullary NaCl concentration, causes a 4-fold increase in inner-medullary Pax2 protein. Treatment with furosemide, which decreases inner-medullary NaCl, reduces inner-medullary Pax2 mRNA and protein. Pax2-specific short interfering RNA increases high NaCl concentration-induced activation of caspase-3 and apoptotic bodies in mIMCD3 cells. We thus conclude that (i) Pax2 is expressed in normal renal medulla, (ii) its expression is regulated there by the normally high and variable NaCl concentration, and (iii) it protects renal medullary cells from high NaCl concentration-induced apoptosis.

Keywords: apoptosis, osmotic stress, renal inner medulla

Pax2 is a transcription factor that is essential for kidney development, promoting the transition of mesenchyme to epithelium (1). In kidneys of normal adult Pax2 protein expression is limited to nuclei of collecting duct cells, with the highest expression in the renal papilla (2). Pax2 mRNA is expressed in collecting ducts and to a lesser extent in distal tubules (2). The function of Pax2 in those segments had not been defined.

In the renal inner medulla, osmolality of interstitial fluid normally is always extremely high mainly because of elevated levels of NaCl and urea, and this osmolality increases with urine concentration (3). Even at the lowest normal level, during water diuresis, osmolality, mainly of NaCl, reaches ≈600 milliosmolal (mosmol)/kg, which is much higher than that of peripheral extracellular fluids (≈300 mosmol/kg). During antidiuresis, the osmolality of renal inner-medullary interstitial fluid increases, exceeding 2,000 mosmol/kg in many rodents. The high levels of NaCl and urea present in the renal inner medulla can cause apoptosis (4), yet the inner medullary cells evidently have protective mechanisms that allow them to survive and function. One such mechanism is that a high NaCl level increases transcription, resulting in a greater abundance of proteins that protect the cells from osmotic stress, including those involved in the accumulation of intracellular organic osmolytes (5) and heat shock proteins (6).

In the present study, our attention was directed to the possibility that Pax2 might be an osmoprotective gene when our initial cDNA microarray analysis showed that high NaCl concentrations increase Pax2 mRNA expression in passage-2 mouse inner-medullary epithelial (p2mIME) cells (7). Stimulated by this result, we extended the study, finding that Pax2 expression is osmoregulated in renal medullary epithelial cells in vivo and in cell culture and that its increased expression protects against high NaCl concentration-induced apoptosis.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Inner-Medullary Epithelial Cell Culture. When passage-2 mouse inner-medullary epithelial (p2mIME) cells cultured from inner medulla as described in ref. 7 had became confluent in the 640 mosmol/kg medium in which they were prepared, osmolality was lowered to 300 mosmol/kg (by removing urea and lowering NaCl) for 2 days before the start of an experiment.

Mouse Inner-Medullary Collecting Duct Cell (mIMCD3 Cell) Culture. mIMCD3 cells (8) (generously provided by S. Gullans, Harvard Medical School, Brookline, MA) were cultured as described in ref. 8. Osmolality of control medium was 300 mosmol/kg. Media to which NaCl was added were substituted for the control medium as indicated.

Animal Experiments. Male Brattleboro rats (180–230 g) from Harlan–Sprague–Dawley were maintained in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle. They had free access to tap water and regular rat chow. Under light anesthesia (isofluorane), osmotic minipumps (model 2001, Alza) were implanted s.c. to deliver 5 ng/h of the V2 receptor-specific vasopressin analog, desamino-Cys-1,d-Arg-8 vasopressin (dDAVP) (Rhone–Poulenc Rorer, Collegeville, PA). Control rats received osmotic minipumps loaded with isotonic saline. After dDAVP or control administration for 3 days, renal inner-medullary collecting ducts were isolated for protein analysis as described in ref. 9.

Two- to 3-month-old male black six-strain mice (Taconic Farms) were injected i.p. with 1.5 mg/20 g furosemide or the same volume of saline solution (controls). Kidneys were removed 4 h later, and inner medullas and cortexes were dissected for RNA and protein analysis.

RNA Isolation. Renal inner-medullary tissue was homogenized in a lysis buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), by using a sawtooth tissue homogenizer, and the homogenates were passed through QIAshredder columns (Qiagen). The same lysis buffer was applied directly to p2mIME and mIMCD3 cells. Total RNA was isolated from the lysates by using RNeasy columns (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's directions. RNA was treated with DNase while bound to the RNeasy column.

cDNA Microarray Studies of p2mIME Cells. Clontech mouse 1.2 nylon filter arrays containing 1,176 cDNAs (Clontech) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Pairs of filters from control and experimental cells were compared. Poly(A) RNA isolated from 25 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed in a reaction that included 33P-labeled ATP. Filters were hybridized overnight at 50°C and washed at a final stringency of 0.5% SDS, 0.1× SSC [standard saline citrate (1× SSC = 0.15 M sodium chloride/0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7)] at 68°C. Images were captured by using a PhosphorImager and analyzed by using the National Institutes of Health software program pscan (http://mscl.cit.nih.gov). Results were normalized to the overall intensity of the individual filters.

Reverse Transcription and Real-Time PCR. Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described in ref. 10 by using primers and an oligonucleotide probe specific for mouse Pax2 (GenBank accession no. X55781). The primers spanned one intron: forward, 5′-GGCATCTGCGATAATGACACA-3′; reverse, 5′-GGTGGAAAGGCTGCTGAACTT-3′; probe, 5′-6FAM -ATCCATCAACAGGATCATCCGGACCA-TAMRA-3′. Multiplex PCR was performed on a Prism 7900 Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems) by using TaqMan PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) to which was added both the specific primers and probes and 18S rRNA primers and 18S probe (Applied Biosystems) labeled with the fluorescent dye VIC. The coamplified 18S cDNA serves as an internal control for reverse transcription and cDNA loading. Triplicates of each sample were analyzed in each PCR run. The results were analyzed with the Applied Biosystems Prism 7900 system software.

Western Blot Analysis. Protein extracts were prepared from cultured cells and homogenates of mouse renal cortex or medulla by using mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER, Pierce) lysis buffer to which protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis) was added, and Western blots were performed with rabbit anti-Pax2 antibody (Zymed) and rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), as described in ref. 11. Protein extracts from rat inner-medullary collecting ducts were prepared and analyzed by Western blot as described (12). Densities of specific bands were quantitated by laser densitometry (Molecular Dynamics).

Immunohistochemistry. Sections (4-μm) of mouse kidney prepared by American HistoLab (Rockville, MD) were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in graded ethanol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 0.3% (vol/vol) hydrogen peroxide in absolute methanol for 30 min. Sections were heated in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave oven at 700 W for 10 min. A Histostain-Plus kit (Zymed) was used for immunolabeling according to the manufacturer's directions by using their nonimmune serum blocking solution. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:400 dilution of rabbit anti-Pax2 antibody (Zymed), followed by biotinylated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG) for 30 min at 37°C and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin for 30 min at 37°C. Labeling was visualized with chromogen diaminobenzidine (Zymed). For double labeling, the Pax2-stained sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-aquaporin 1 water channel (AQP1) antibody (1:400 dilution) or aquaporin 2 water channel (AQP2) (1:600 dilution) (both from M. Knepper, National Institutes of Health), followed by biotinylated secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG), as above, and alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (Zymed). The second label was visualized with chromogen fast red (Zymed). Finally, the slides were counterstained with hematotoxylin.

Reporter Assay of Pax2 Transcriptional Activity. We prepared PRS4-IL-2minGL3, a luciferase reporter of Pax2 transcriptional activity, as follows. We copied a DNA segment containing five tandem repeats of the Pax2 DNA-binding element by PCR from the reporter plasmid PRS4-CAT (13) (provided by G. R. Dressler, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor) and inserted it into an XhoI site upstream of the IL-2 minimum promoter in the IL-2minGL3 reporter plasmid (14) (provided by S. N. Ho, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla). Fidelity of the Pax2 elements was confirmed by sequencing. PRS4-IL-2minGL3 was transfected into mIMCD3 cells at 300 mosmol/kg, by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sixteen hours later, fresh 300, 400, 500, 550, or 600 mosmol/kg medium was substituted, and, 24 h after that, cells were scraped in 200 μl of passive lysis 5× buffer (Promega). Total protein was measured (Pierce), and luciferase activity was determined on duplicate 10 μl of aliquots by using a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Transcriptional activity of Pax2 is presented as light units per μg of protein, normalized to the mean value at 300 mosmol/kg.

mIMCD3 Cells Stably Expressing Pax2 Short Interfering RNA (siRNA). The hairpin siRNA expression vector, pRNATin-H1.2/Neo was from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). Sense siRNA against mouse Pax2 was 5′-AATGTGTCAGGCACACAGACG-3′ (15). Sense siRNA against luciferase was 5′-AACTTACGCTGAGTACTTCGA-3′ (16). The hairpin siRNAs were designed by using siRNA construct builder (Genescript) and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Sense and antisense hairpin siRNAs were annealed in NEBuffer 2 (New England Biolabs) for 4 min at 95°C followed by incubation for 10 min at 70°C, then slowly cooled to room temperature. The annealed Pax2 siRNAs were inserted between the BamHI and HindIII sites in pRNATin-H1.2/Neo and transfected into mIMCD3 cells by using Lipofectamine 2000. Single colonies were selected in medium containing 700 mg/liter G418 and examined by Western analysis for Pax2 protein expression, as above. Expression of Pax2 is greatly reduced in clone 9, which was used for subsequent experiments.

Detection of Apoptosis by Hoechst 33258 Staining. Cells were plated on an eight-chamber slide and grown for 2 days at 300 mosmol/kg, then osmolality was left the same or increased to 500, 550, or 600 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl for 9 h. The cells were fixed in 10% formalin (Fisher Scientific) for 15 min, washed three times with PBS, and stained with 10 μg/ml Hoechst-33258 DNA dye (Molecular Probes) for 15 min. After staining, the slides were mounted with antifade solution (Molecular Probes).

Statistical analysis was performed by using instat (GraphPad, San Diego). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = no. of independent experiments). Differences were considered significant for P < 0.05.

Results

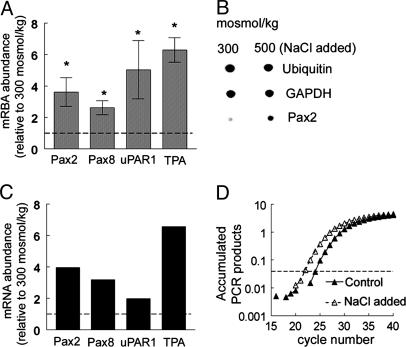

High NaCl Concentration Increases Pax2 mRNA Abundance in p2mIME Cells. We used Clontech mouse 1.2 microarrays containing 1,176 different mouse cDNAs to identify genes whose mRNA abundance in p2mIME cells is affected when medium NaCl concentration is elevated. Expression of four genes increases significantly 4 h after raising osmolality from 300 to 500 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl, namely Pax2 (paired box protein 2, GenBank accession no. X55781), Pax8 (paired box protein 8, GenBank accession no. X57487), uPAR1 (urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor, GenBank accession no. X62700), and TPA (tissue plasminogen activator precursor, GenBank accession no. J03520) (Fig. 1 A and B). Increased expression of all four was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 1 C and D). In the study that follows, we focused on Pax2, whose mRNA increases 4-fold (Fig. 1 A and C).

Fig. 1.

High NaCl levels increase expression of Pax2 mRNA in p2mIME cells. p2mIME cells were cultured at 640 mosmol/kg. After being confluent, the cells were switched to 300 mosmol/kg serum-free medium for 48 h. Then the osmolality of the medium was increased to 500 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl for 4 h, followed by RNA extraction for cDNA array (A and B) and real-time RT-PCR (C and D). (A) Densitometric analysis of mRNA in microarray. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM of three experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05. (B) Representative microarray results. (C) Confirmation of array results by real-time RT-PCR. (D) Representative amplification plot of real-time PCR.

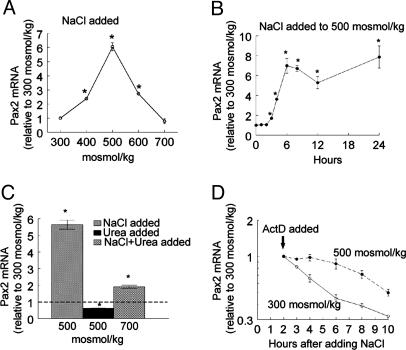

High NaCl Concentration Increases Pax2 mRNA and Protein in mIMCD3 Cells, but High Urea Concentration Does Not. Both NaCl and urea normally are high in the renal inner medulla. mIMCD3 are cells derived from mouse inner-medullary collecting ducts. We used these cells to compare the effects of NaCl and urea on expression of Pax2. In mIMCD3 cells, as in p2mIME cells, elevating osmolality from 300 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl increases Pax2 mRNA (Fig. 2 A and B). The increase is maximal (6-fold) at 500 mosmol/kg, is less at 600 mosmol/kg, and is absent at 700 mosmol/kg (Fig. 2 A). At 500 mosmol/kg, Pax2 mRNA increases significantly within 6 h and remains elevated for at least 24 h (Fig. 2B). In contrast, adding urea to 500 mosmol/kg for 6 h reduces Pax2 mRNA (Fig. 2C). Addition of NaCl and urea in combination elevates Pax2 mRNA, but the increase is less than adding NaCl alone (Fig. 2C). High NaCl levels also transiently enhance the stability of Pax2 mRNA. At 300 mosmol/kg, the half-life of Pax2 mRNA is ≈4 h (Fig. 2D). Raising osmolality to 500 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl inhibits degradation of Pax2 mRNA but only for ≈6 h. The effects of high NaCl and urea levels on Pax2 protein abundance (Fig. 3) are similar to those on its mRNA abundance (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of high NaCl or urea levels on expression of Pax2 mRNA in mIMCD3 cells. RNA abundance was measured by real-time RT-PCR. (A) Osmolality was increased to 400, 500, 600, or 700 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl for 6 h. (B) Osmolality was increased to 500 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl for 6, 12, 18, or 24 h. (C) Osmolality was increased for 6 h by adding NaCl or urea either alone to 500 mosmol/kg or combined to 700 mosmol/kg. (D) Pax2 mRNA stability. Actinomycin (ActD; 5 μg/ml) was added 2 h after osmolality was increased to 500 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM of three experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05.

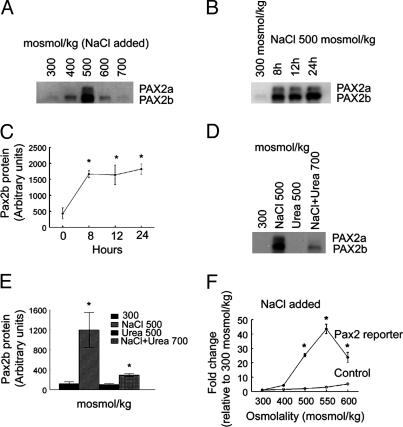

Fig. 3.

Effect of high NaCl and/or urea levels on expression and transcriptional activity of Pax2 protein in mIMCD3 cells. Pax2a and Pax2b are splice variants. (A) Osmolality of medium was increased to 400, 500, 600, or 700 mosmol/kg for 8 h. (B and C) Osmolality of medium was increased to 500 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl for 8, 12, and 24 h. (D and E) Osmolality was increased to 500 mosmol/kg by adding either NaCl or urea alone or to 700 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl and urea combined. (F) mIMCD3 cells were transfected with luciferase reporter constructs containing either specific binding elements for Pax2 or no specific binding elements (control). Osmolality was increased to 400, 500, 550, or 600 mosmol/kg 24 h after transfection at 300 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h later and is normalized to that of the cells at 300 mosmol/kg. (C, E, and F) Values are expressed as the means ± SEM of three experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05.

Pax2 Transcriptional Activity Is Increased by High NaCl Concentration. Pax2 is a transcription factor (17). We used a luciferase reporter containing the consensus Pax2 DNA element (18) to test the effect of high NaCl levels on Pax2 transcriptional activity. Raising osmolality by adding NaCl greatly increases Pax2 transcriptional activity (Fig. 3F). The maximal increase is 42-fold at 550 mosmol/kg. As a control, a high NaCl concentration does not increase the activity of a reporter lacking the Pax2 DNA element (Fig. 3F). Thus, the Pax2 that is increased by high NaCl levels is transcriptionally active.

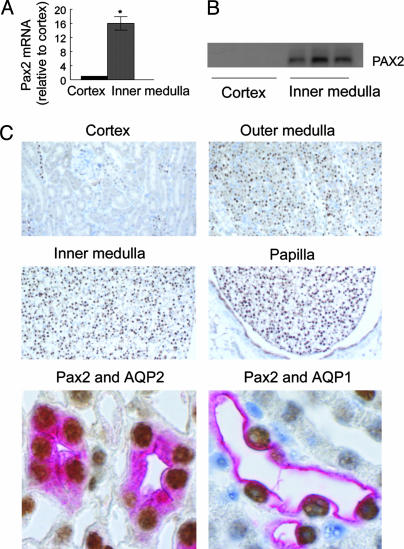

Pax2 mRNA and Protein Expression Are High in the Renal Inner Medulla in Vivo. Interstitial NaCl concentration normally is always elevated in renal inner medulla but not in the renal cortical labyrinth (3). Consistent with the findings in cell culture, Pax2 mRNA (Fig. 4A) and protein (Fig. 4B) abundances are much greater in mouse renal inner medulla, where the interstitial NaCl concentration is high, than in renal cortex, where it is not. Most cells express Pax2 protein in the inner medulla, whereas few express it in the cortex (Fig. 4C). Within the inner medulla, Pax2 expression increases along the corticomedullary axis, being greater in inner than in outer medulla and greatest in the renal papilla (Fig. 4C), corresponding to the known osmotic gradient. This pattern of expression in renal medulla is similar to that of the stress proteins HSP70 and OSP94 (19, 20).

Fig. 4.

Location of Pax2 mRNA and protein in normal mouse kidney. (A and B) Cortex versus inner medulla. (A) Pax2 mRNA. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM of three experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05. (B) Pax2 protein. Each lane is from a different mouse. (C) Immunohistochemistry of Pax2 (brown) in mouse kidney. Pink color indicates either AQP2 (labeling collecting duct cells) or AQP1 (labeling descending thin limb cells) in inner medulla.

We used double staining to identify which kinds of cells express Pax2. Collecting duct cells, whether located in the renal cortex or medulla, express the AQP2 (21). Pax2 and AQP2 colocalize in inner-medullary cells, indicating that inner-medullary collecting ducts express high levels of Pax2 (Fig. 4C). They also colocalize in the outer medulla (data not shown), where the interstitial NaCl concentration also is high (3). Interestingly, cells in the renal cortex that express Pax2 also express AQP2 and vice versa (data not shown), indicating that they are cortical collecting duct cells. Cortical collecting ducts are bundled in medullary rays. Although interstitial NaCl concentration is known to be high throughout the renal medulla and at systemic levels in the renal cortical labyrinth (3), we are unaware of any measurements of interstitial NaCl level in medullary rays, so the explanation for PAX2 expression in cortical collecting ducts remains uncertain.

AQP1 is expressed in the thin descending limb of Henle's loop and in proximal tubule cells (21). Pax2 and AQP1 colocalize in some cells in the inner medulla (Fig. 4C) but not in cortex (data not shown). Thus, thin descending limb cells also express Pax2. A minority of cells in the renal medulla do not express Pax2 (Fig. 4C), but we have not positively identified them.

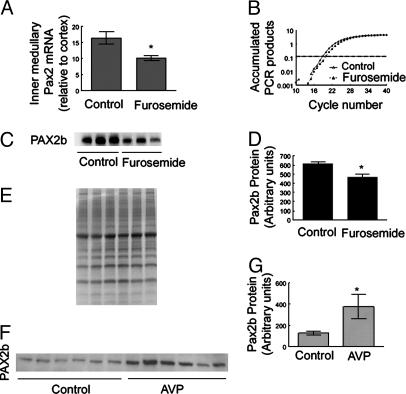

Pax2 Expression Is Osmotically Regulated in Vivo. Renal inner-medullary interstitial NaCl concentration is reduced by diuretics, like furosemide, and increased by vasopressin-induced antidiuresis. To determine whether Pax2 is osmoregulated in vivo as it is in cell culture, we tested the effect of furosemide and the V2 receptor-specific vasopressin analog dDAVP on Pax2 expression. In mice, i.p. injection of 1.5 mg of furosemide per 20 g of body weight greatly reduces urine osmolality within 4 h (data not shown; see ref. 22), associated with reduced renal inner-medullary osmolality. Furosemide decreases inner-medullary Pax2 mRNA and protein (Fig. 5 A–D). Pax2 mRNA decreases by ≈40% (Fig. 5 A and B), and Pax2 protein decreases by ≈25% (Fig. 5 C and D). Because of defective vasopressin synthesis, Brattleboro rats have low urinary and inner-medullary osmolality (23). Administration of the exogenous vasopressin analog dDAVP for 3 days increases their urine concentration and inner-medullary osmolality (24). After 3 days of dDAVP administration, Pax2 protein in the renal inner medullas of Brattleboro rats increases by ≈4-fold (Fig. 5 F and G). We conclude that Pax2 is osmoregulated in vivo, like it is in cell culture.

Fig. 5.

Effects of furosemide and dDAVP on renal Pax2 mRNA and protein in vivo.(A–D) Kidneys were removed for analysis 4 h after i.p. injection of 1.5 mg of furosemide per 20 g of body weight. (A) Inner-medullary Pax2 mRNA by real-time RT-PCR. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM of three experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05. (B) Representative amplification plot of real-time PCR. (C and D) Mouse inner-medullary Pax2 protein. (C) Western blot. Each lane is from a different mouse. (D) Densitometric analysis of C. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of three experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05. (E) Coomassie blue staining of the gel from which the Western blot in C was taken demonstrates equal protein loading of the lanes. (F and G) Brattleboro rat inner-medullary Pax2 protein. Rats were given 5 ng/h dDAVP in saline or saline alone (control) by s.c. minipump for 3 days. (F) Western blot. Each lane is from a different rat. (G) Densitometric analysis of F. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM of three experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05.

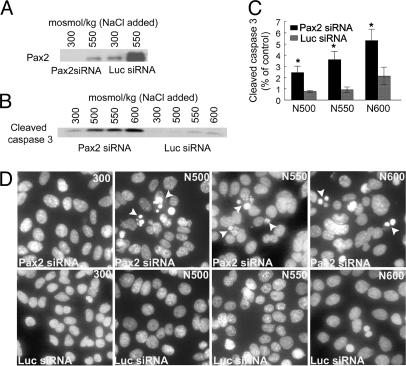

Pax2 Expression Protects Against High NaCl Concentration-Induced Apoptosis. To determine whether Pax2 expression affects the sensitivity of mIMCD3 cells (4, 25) to high NaCl levels, we used a Pax2-specific siRNA to suppress high NaCl concentration-induced Pax2 expression in stably transfected mIMCD3 cells. Expression of this specific siRNA reduces Pax2 protein both at 300 mosmol/kg and after adding NaCl to 550 mosmol/kg, compared with control (luciferase) siRNA (Fig. 6A). We measured activated caspase-3 as an index of apoptosis. Increasing osmolality to 500, 550, or 600 mosmol/kg by adding NaCl for 9 h greatly increases caspase-3 activity in cells transfected Pax2-specific siRNA but much less in control cells transfected with luciferase siRNA (Fig. 6 B and C). As another index of apoptosis, we examined nuclear morphology (Hoechst 33258 staining) 9 h after adding NaCl to 500, 550, and 600 mosmol/kg (Fig. 6D). Specific Pax2 siRNA greatly increases the number of apoptotic bodies compared with control (luciferase) siRNA. We conclude that high NaCl concentration-induced Pax2 expression protects inner-medullary cells by inhibiting apoptosis.

Fig. 6.

Pax2 expression reduces high NaCl concentration-induced apoptosis. Pax2 siRNA or control (luciferase) siRNA was stably transfected into mIMCD3 cells. Osmolality was increased by adding NaCl for 9 h. (A) Specific Pax2 siRNA decreases NaCl-induced Pax2 protein expression. (B) Pax2 siRNA increases NaCl-induced activation of caspase-3. (C) Densitometric analysis of cleaved caspase-3 normalized to control at 300 mosmol/kg. Values are expressed as the means ± SEM of five experiments. *, P ≤ 0.05. (D) Hoechst 33258 staining of DNA. Arrows indicate apoptotic bodies.

Discussion

Expression of the paired box genes is known to be crucial for development, but in addition, expression of several of them persists in normal adult tissues, including Pax8 in thyroid (26), Pax5 in testis (27), and Pax2 in epididymis (28) and certain kidney cells (2). The role of these so-called developmental genes in normal adult tissues has not been well understood. However, now we know that Pax2 protects medullary cells against the stress of high NaCl levels, giving a rationale for its expression in adult renal inner medullas.

Within the kidney, osmolality of interstitial fluid in the cortex labyrinth is at ≈300 mosmol/kg, similar to that elsewhere in the body. In the renal medulla, osmolality of interstitial fluid is higher and varies with urine concentration. Osmolality increases along the medullary axis, becoming highest at the tip of the renal papilla, where it exceeds 2,000 momsol/kg in rodents during antidiuresis (3). Pax2 protein expression increases in the same manner along the cortical–medullary osmolality gradient, being highest at the tip of the papilla (Fig. 4). Furthermore, Pax2 expression changes with osmolality in the renal medulla. Administration of dDAVP, which increases medullary interstitial osmolality, also increases medullary Pax2 protein (Fig. 5), and the diuretic furosemide, which decreases medullary interstitial osmolality, also decreases Pax2 protein. Thus, the stress of hyperosmolality is a very strong stimulus for induction of Pax2 in the renal medulla in vivo.

We are aware of only two other examples of stress-related expression of Pax2 in the kidney. Pax2 is not expressed normally in renal proximal tubules but is expressed there transiently at the beginning of recovery from the acute tubular necrosis induced by administration of folic acid (2) or by ischemia (29). Because Pax2 expression is associated with regeneration of the cells, it was proposed that, during the regeneration, developmental paradigms might be recapitulated, which is evidently not the case in the renal medulla, however, because expression of Pax2 occurs there in the absence of cellular proliferation (7).

Pax2 expression inhibits apoptosis during kidney development (30, 31) and reduces apoptosis in tumor cell lines (32, 33). The stress of a high NaCl concentration causes apoptosis in mIMCD3 cells when osmolality is acutely raised to >600 mosmol/kg but not to 500 mosmol/kg (4). We now find that siRNA-induced reduction of Pax2 causes apoptosis in these cells even at 500 mosmol/kg (Fig. 6). Two indicators of apoptosis, namely caspase-3 activation and the appearance of apoptotic bodies, occur in mIMCD3 cells at 500 mosmol/kg when expression of Pax2 is prevented by specific siRNA but not with a control siRNA that does not prevent Pax2 expression. Therefore, Pax2 expression not only is induced by the stress of high NaCl levels but also helps protect the cells from apoptosis caused by that stress.

It is intriguing that, within the adult kidney, Pax2 is expressed in cortical as well as medullary collecting duct cells. Cortical collecting ducts are segregated in medullary rays, which may provide an environment different from that in the cortical labyrinth, where there is a high rate of vascular perfusion. Perhaps Pax2 expression occurs in response to this environment. In the outer medulla, NaCl transport out of thick ascending limbs raises the NaCl concentration around adjacent collecting ducts. It is conceivable that this elevation of NaCl concentration also occurs in medullary rays, where thick ascending limbs are in parallel proximity to collecting ducts. Although Pax2 expression could be accounted for by such a high NaCl concentration, we are not aware of direct evidence for a high interstitial NaCl concentration in this region. Another aspect is that oxygen tension is low in medullary rays, like it is in the medulla. Low oxygen tension can result in generation of reactive oxygen species (34, 35), a possible alternative or additional signal for Pax2 expression.

To elucidate how high NaCl levels increase Pax2 mRNA abundance, we measured Pax2 mRNA stability. A high NaCl concentration stabilizes Pax2 mRNA but only for ≈6 h (Fig. 2D), whereas the mRNA levels remain elevated for at least 24 h (Fig. 2B). Given the otherwise short half-life of Pax2 mRNA (≈4 h, Fig. 2D), the transient stabilization of Pax2 mRNA by high NaCl levels is insufficient to account for its prolonged elevation. Therefore, high NaCl concentrations may also increase transcription of Pax2. There are already many other examples of genes whose transcription is increased by high concentrations of NaCl, including those involved in accumulation of intracellular organic osmolytes (5) and heat shock proteins (6).

In summary, Pax2 mRNA and protein are induced in renal cell culture by high NaCl levels but not by high urea levels. Pax2 expression protects the cells in culture from high NaCl concentration-induced apoptosis. Pax2 also varies with osmolality in renal medullas of normal adult kidneys, where it presumably protects the cells in vivo from the physiologically occurring stress of high NaCl levels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark A. Knepper for AQP1 and AQP2 antibody, Gregory R. Dressler for Pax2 reporter construct, and Steffan N. Ho for IL-2-minPGL3 construct. B.W.M.v.B. was supported by the Nephrogenic Diabetes Insipidus Foundation, the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research, and De Drie Lichten Foundation.

Author contributions: Q.C., J.D.F., H.L.B., and M.B. designed research; Q.C., N.I.D., and B.W.M.v.B. performed research; Q.C., N.I.D., J.D.F., H.L.B., and M.B. analyzed data; and Q.C. and M.B. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: mIMCD cell, mouse inner-medullary collecting duct cell; p2mIME cell, passage-2 mouse inner-medullary epithelial cell; mosmol, milliosmolal; siRNA, small interfering RNA; dDAVP, desamino-Cys-1,d-Arg-8 vasopressin; AQP1, aquaporin 1 water channel; AQP2, aquaporin 2 water channel.

References

- 1.Torban, E. & Goodyer, P. (1998) Exp. Nephrol. 6, 7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imgrund, M., Grone, E., Grone, H. J., Kretzler, M., Holzman, L., Schlondorff, D. & Rothenpieler, U. W. (1999) Kidney Int. 56, 1423-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bankir, L. (1996) in The Kidney, eds. Brenner B. M. & Rector, F. (Saunders, Philadelphia), pp. 571-606.

- 4.Michea, L., Ferguson, D. R., Peters, E. M., Andrews, P. M., Kirby, M. R. & Burg, M. B. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. 278, F209-F218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Perez, A. & Burg, M. B. (1991) Physiol. Rev. 71, 1081-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borkan, S. C. & Gullans, S. R. (2002) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64, 503-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang, Z., Cai, Q., Michea, L., Dmitrieva, N., Andrews, P. & Burg, M. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. 283, F203-F208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rauchman, M. I., Nigam, S. K., Delpire, E. & Gullans, S. R. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. 265, F416-F424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou, C. L., DiGiovanni, S. R., Luther, A., Lolait, S. J. & Knepper, M. A. (1995) Am. J. Physiol. 269, F78-F85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferraris, J. D., Williams, C. K., Persaud, P., Zhang, Z., Chen, Y. & Burg, M. B. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 739-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kultz, D., Madhany, S. & Burg, M. B. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13645-13651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Balkom, B. W., Hoffert, J. D., Chou, C. L. & Knepper, M. A. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. 286, F216-F224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai, Y., Lechner, M. S., Nihalani, D., Prindle, M. J., Holzman, L. B. & Dressler, G. R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1217-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trama, J., Lu, Q., Hawley, R. G. & Ho, S. N. (2000) J. Immunol. 165, 4884-4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies, J. A., Ladomery, M., Hohenstein, P., Michael, L., Shafe, A., Spraggon, L. & Hastie, N. (2004) Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 235-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elbashir, S. M., Harborth, J., Lendeckel, W., Yalcin, A., Weber, K. & Tuschl, T. (2001) Nature 411, 494-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lechner, M. S. & Dressler, G. R. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21088-21093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fickenscher, H. R., Chalepakis, G. & Gruss, P. (1993) DNA Cell Biol. 12, 381-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santos, B. C., Chevaile, A., Kojima, R. & Gullans, S. R. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 274, F1054-F1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos, B. C., Pullman, J. M., Chevaile, A., Welch, W. J. & Gullans, S. R. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. 284, F564-F574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knepper, M. A., Wade, J. B., Terris, J., Ecelbarger, C. A., Marples, D., Mandon, B., Chou, C. L., Kishore, B. K. & Nielsen, S. (1996) Kidney Int. 49, 1712-1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dmitrieva, N. I., Cai, Q. & Burg, M. B. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2317-2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valtin, H. & Edwards, B. R. (1987) Kidney Int. 31, 634-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kishore, B. K., Terris, J. M. & Knepper, M. A. (1996) Am. J. Physiol. 271, F62-F70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos, B. C., Chevaile, A., Hebert, M. J., Zagajeski, J. & Gullans, S. R. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 274, F1167-F1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zannini, M., Francis-Lang, H., Plachov, D. & Di, L. R. (1992) Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 4230-4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams, B., Dorfler, P., Aguzzi, A., Kozmik, Z., Urbanek, P., Maurer-Fogy, I. & Busslinger, M. (1992) Genes Dev. 6, 1589-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oefelein, M., Grapey, D., Schaeffer, T., Chin-Chance, C. & Bushman, W. (1996) J. Urol. 156, 1204-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeshima, A., Maeshima, K., Nojima, Y. & Kojima, I. (2002) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 2850-2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark, P., Dziarmaga, A., Eccles, M. & Goodyer, P. (2004) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15, 299-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dziarmaga, A., Clark, P., Stayner, C., Julien, J. P., Torban, E., Goodyer, P. & Eccles, M. (2003) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 2767-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muratovska, A., Zhou, C., He, S., Goodyer, P. & Eccles, M. R. (2003) Oncogene 22, 7989-7997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buttiglieri, S., Deregibus, M. C., Bravo, S., Cassoni, P., Chiarle, R., Bussolati, B. & Camussi, G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4136-4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandel, N. S., Vander Heiden, M. G., Thompson, C. B. & Schumacker, P. T. (2000) Oncogene 19, 3840-3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paddenberg, R., Ishaq, B., Goldenberg, A., Faulhammer, P., Rose, F., Weissmann, N., Braun-Dullaeus, R. C. & Kummer, W. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 284, L710-L719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]