Abstract

Context:

Uterine leiomyomas (fibroids) are the most common benign tumors in women. Recently, three populations of leiomyoma cells were discovered on the basis of CD34 and CD49b expression, but molecular differences between these populations remain unknown.

Objective:

To define differential gene expression and signaling pathways in leiomyoma cell populations.

Design:

Cells from human leiomyoma tissue were sorted by flow cytometry into three populations: CD34+/CD49b+, CD34+/CD49b−, and CD34−/CD49b−. Microarray gene expression profiling and pathway analysis were performed. To investigate the insulinlike growth factor (IGF) pathway, real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction, immunoblotting, and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation studies were performed in cells isolated from fresh leiomyoma.

Setting:

Research laboratory.

Patients:

Eight African American women.

Interventions:

None

Main Outcomes Measures:

Gene expression patterns, cell proliferation, and differentiation.

Results:

A total of 1164 genes were differentially expressed in the three leiomyoma cell populations, suggesting a hierarchical differentiation order whereby CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells differentiate to CD34+/CD49b− intermediary cells, which then terminally differentiate to CD34−/CD49b− cells. Pathway analysis revealed differential expression of several IGF signaling pathway genes. IGF2 was overexpressed in CD34+/CD49b− vs CD34−/CD49b− cells (83-fold; P < 0.05). Insulin receptor A (IR-A) expression was higher and IGF1 receptor lower in CD34+/CD49b+ vs CD34−/CD49b− cells (15-fold and 0.35-fold, respectively; P < 0.05). IGF2 significantly increased cell number (1.4-fold; P < 0.001), proliferation indices, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) phosphorylation. ERK inhibition decreased IGF2-stimulated cell proliferation.

Conclusions:

IGF2 and IR-A are important for leiomyoma stem cell proliferation and may represent paracrine signaling between leiomyoma cell types. Therapies targeting the IGF pathway should be investigated for both treatment and prevention of leiomyomas.

Microarray and functional studies of three leiomyoma cell populations, including stem cells, implicated the IGF2 pathway in paracrine signaling and as important for cell proliferation.

Uterine leiomyomas are benign tumors that arise from the monoclonal expansion of uterine smooth muscle cells (1). Symptoms of leiomyomas include irregular and heavy menstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, pressure symptoms on the bowel and bladder, and recurrent pregnancy loss and infertility. Leiomyomas have a considerable public health impact; they are estimated to cause symptoms in up to 30% of reproductive-age women, with more than 200,000 surgeries performed in the United States annually to treat leiomyomas, leading to an annual cost of $5.9 to $34.4 billion (1). Despite the prevalence of leiomyomas and their impact on women’s health, there are currently no US Food and Drug Administration–approved medications for the long-term treatment of leiomyomas. Additionally, currently available medications are limited by side effects, and tumors tend to recur upon discontinuation of treatment (2). Improving our knowledge of the specific etiology and pathophysiology of leiomyomas is necessary to develop better therapies.

Recently, a small population of cells with stem cell–like features was discovered in uterine leiomyomas using the side population technique (3, 4). We demonstrated that these cells were necessary for steroid-dependent tumor growth, and grafts containing leiomyoma stem cells grew into significantly larger tumors when placed underneath mouse kidney capsules compared with grafts without stem cells (3). Unfortunately, the side population technique is expensive and sensitive to slight staining variations, and the Hoechst stain is toxic to cells (5). We recently reported an alternative approach to isolating leiomyoma stem cells using flow cytometry on the basis of expression of the cell surface markers CD34 and CD49b (6). This method revealed three distinct leiomyoma cell populations: CD34+/CD49b+ (6%), CD34+/CD49b− (7%), and CD34−/CD49b− (87%) cells. CD34+/CD49b+ cells were highly enriched in side population (stem) cells that expressed high levels of stem cell markers such as OCT4, KLF4, NANOG, and SOX2, and demonstrated high capacity for in vitro colony formation, all characteristics that support their progenitor status (6).

Currently, the molecular characteristics of the three cell types are unknown. Given the low levels of estrogen and progesterone receptor expression in leiomyoma side population and CD34+/CD49b+ cells (3, 6), we hypothesized that stem cells receive paracrine signals for proliferation. Additionally, we hypothesized that CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells are capable of asymmetric division, allowing both self-renewal and the production of intermediary daughter cells, or CD34+/CD49b− cells, which ultimately develop into fully differentiated leiomyoma cells, or CD34−/CD49b− cells. The objective of the current study was to determine the differential gene expression between the three populations and identify and characterize critical pathways that may underlie leiomyoma pathogenesis and may be potential targets for new therapies.

Materials and Methods

Tissue acquisition and processing

Human uterine leiomyoma tissue was obtained at the time of myomectomy or hysterectomy from eight premenopausal African American women (age range, 33 to 49 years) who provided informed consent. Most uteri contained multiple fibroid tumors. The size of the tumors biopsied for this study varied from 4.8 cm to 21.3 cm. The procedure was conducted at Northwestern Memorial Prentice Women’s Hospital under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University. No subjects had received any hormonal or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist or antagonist treatments in the prior 6 months. Tissues were dissociated and cells isolated as previously described (7).

Cell culture

All experiments were performed in cells isolated from fresh tissues and cultured without passaging. Leiomyoma cells were cultured on cell culture plates and in rolling suspension using a low profile roller (IBI Scientific, Peosta, IA) in a humidified atmosphere in 5% CO2 at 37°C. For IGF2 treatment, pro-IGF2 peptide (Humanzyme, Chicago, IL) at a concentration of 10, 50, or 100 ng/mL was added with 0.1% bovine serum albumin in phenol red–free and serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium. Control cells were treated with vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) with 0.1% bovine serum albumin in phenol red–free and serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium. For inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, 10 μM mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor U0126 was added to the culture media 2 hours prior to adding IGF2 or vehicle. This concentration and incubation period of U0126 have been previously described (8).

Antibody-based cell sorting

Cells were incubated with fluorescently labeled antibodies against CD45, CD34, and CD49b to identify CD34+/CD49b+, CD34+/CD49b−, and CD34−/CD49b− populations, while excluding CD45+ (hematopoietic) cells, as previously described (7). All antibodies used are listed in Supplemental Table 1 (33KB, xls) . Cells were either analyzed using the LSR Fortessa system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) or sorted and collected using a FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). The approximate yield is 0.5 × 106 viable stem cells from 20 g of leiomyoma tissue, which can be sorted within 3 hours using FACSAria.

Microarray and data analysis

Microarray was performed in triplicate using RNA isolated from leiomyoma cells from eight premenopausal African American women. After sorting on the basis of CD34 and CD49b expression, total RNA was extracted from each population of leiomyoma cells using the RNAeasy mini kit or micro kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The micro kit was used for samples containing less than 100,000 cells. The Illumina Human HT-12 microarray platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) was used for expression profiling. Hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis were performed to assess sample relationships and variability. The fold-change threshold was set to ±1.5, with a false discovery rate < 5%. Pathway analysis was performed using MetaCore (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY), the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, and Gene Ontology.

qRT- PCR

Total RNA was isolated from either cultured or sorted leiomyoma cells using the RNAeasy mini kit or micro kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 μg RNA using qScript cDNA supermix (Quantabio, Beverly, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed as previously described (9). Insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF1), IGF2, IGF binding protein 3 (IGFBP3), insulin receptor A (IR-A), IGF1 receptor (IGF1R), and IGF2 receptor (IGF2R) messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were determined by qRT-PCR using the ABI TaqMan gene expression system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All primers used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table 2 (32KB, xls) . Gene expression data were normalized to TBP or HPRT1. Samples were processed in the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and data were collected with SDS 2.3 software (Applied Biosystems).

Immunoblotting

Protein from leiomyoma cells was isolated using a radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis and extraction buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Protein from cultured cells was quantified using the BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific), and 20 μg of protein was diluted with reducing 4X LDS Sample Buffer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), electrophoresed on 4% to 12% Novex Bis-Tris polyacrylamide precast gels (Life Technologies), and transferred onto polyvinyl difluoride membranes. For sorted cells, equal protein loading was estimated using cell counts as reported by the FACSAria cell sorter, with protein isolated from 150,000 cells in each group and protein separation performed as described previously. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) and 0.2% Tween-20 and probed with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) were diluted in 5% milk at 1:6000 and incubated with membranes at room temperature for one hour. The membranes were washed in TBS with 0.2% Tween-20 three times, followed by one wash in TBS. Femto (Thermo Scientific) or Luminata Crescendo (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for detection. Film was developed in a Konica Minolta developer (Maitland, FL), and Image Studio Lite (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) software was used to quantify immunoblots.

Cell proliferation assay

A Click-iT 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Life Technologies) was used to measure cell proliferation after overnight treatment of cells in rolling suspension with vehicle or 100 ng/mL IGF2. EdU incorporation was allowed to occur for 1.5 to 2 hours at 37°C, followed by antibody staining for CD34 and CD49b. The Click-iT reaction was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Analysis was performed using the LSR Fortessa System (BD Biosciences). Cells were also counted after overnight treatment, and fold change from vehicle to IGF2-treated cells was calculated.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed using primary cells from at least three subjects. Data were analyzed using paired Student t tests or repeated measures analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction for three pairwise comparisons, using Microsoft Excel and SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The microarray data were analyzed using multiple t tests, with differential expression defined as fold change > 1.5 and false discovery rate < 5%. For qRT-PCR, fold change was calculated relative to CD34−/CD49b−cells.

Results

Differential gene expression in CD34+/CD49b+, CD34+/CD49b−, and CD34−/CD49b− cell populations

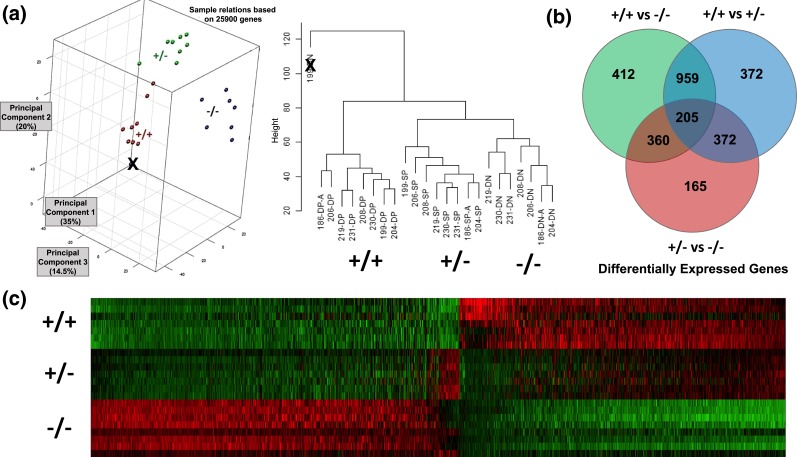

To identify the molecular differences between the three leiomyoma cell populations, we performed a comprehensive gene expression microarray on sorted cell populations from fibroid tissues of eight African American women. Principal components and hierarchical clustering analyses verified distinct clustering of the 24 samples into three cell populations except for a single CD34−/CD49b− (double negative) sample, which was eliminated [Fig. 1(a)]. Statistical analysis of the microarray results revealed that CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells had significant differential expression of 1164 genes compared with CD34+/CD49b− and CD34−/CD49b− cells, with 401 downregulated and 763 upregulated genes [Fig. 1(b)]. The gene expression pattern illustrated by heat map [Fig. 1(c)] and pathway analysis suggest a hierarchical differentiation pattern, whereby CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells first differentiate to CD34+/CD49b− intermediary cells, which terminally differentiate to CD34−/CD49b− cells.

Figure 1.

(a) Principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering of microarray data, showing that the three sorted leiomyoma cell types are molecularly distinct. In the PCA chart, red is CD34+/CD49b+ (double positive, DP), green is CD34+/CD49b− (single positive, SP), and blue is CD34−/CD49b− (double negative, DN). The labeling of each sample (e.g., 186-DP-A) is arbitrary, and was done for organizational purposes only. The only outlier (marked with X) was also the only sample for which there were RNA quality concerns prior to microarray, and was therefore excluded from further analysis. (b) Venn diagram showing the number of differentially expressed genes between the three cell populations. (c) Heatmap of microarray data with visual evidence of a transition from the CD34+/CD49b+ (+/+) to CD34+/CD49b− (+/−) to CD34−/CD49b− (−/−) cell populations.

Results from the pathway analysis of the microarray data are shown in Table 1. Genes involved in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition were prominent in all three comparisons (CD34+/CD49b+ vs CD34+/CD49b−, CD34+/CD49b+ vs CD34−/CD49b−, and CD34+/CD49b− vs CD34−/CD49b−). Intriguingly, pathway analysis also revealed overrepresentation of multiple pathways in which IGF signaling is known to play a role, including proliferation, apoptosis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and pathways in cancer and glucose regulation. Additionally, genes from the TGF and WNT signaling pathways were differentially expressed, consistent with prior literature on uterine leiomyomas.

Table 1.

Pathway Analysis Results

| Pathway | Comparison |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CD34+/CD49b+ vs CD34+/CD49b− | CD34+/CD49b+ vs CD34−/CD49b− | CD34+/CD49b− vs CD34−/CD49b− | |

| Regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitiona | X | X | X |

| Cytoskeleton remodelinga | X | X | X |

| Chemokines and adhesion | X | X | X |

| TGF, WNT, and cytoskeletal remodeling | X | X | X |

| Glucose regulationa | X | X | X |

| Cell migrationa | X | X | X |

| Regulation of cell motilitya | X | X | X |

| Response to woundinga | X | X | X |

| TGF-β signaling pathway | X | X | X |

| Breast cancera | X | X | |

| Regulation of cell proliferationa | X | X | |

| Apoptosisa | X | X | |

| Pathways in cancera | X | X | |

| Cell differentiationa | X | X | |

| MAPK signaling pathwaya | X | X | |

| Notch signaling pathway | X | X | |

| ECM remodelinga | X | X | |

| Inflammatory responsea | X | X | |

Only pathways that involve genes that were differentially expressed in more than one comparison are included.

Abbreviations: ECM, extracellular matrix; TGF, transforming growth factor.

Pathways in which the IGF system is thought to play a role.

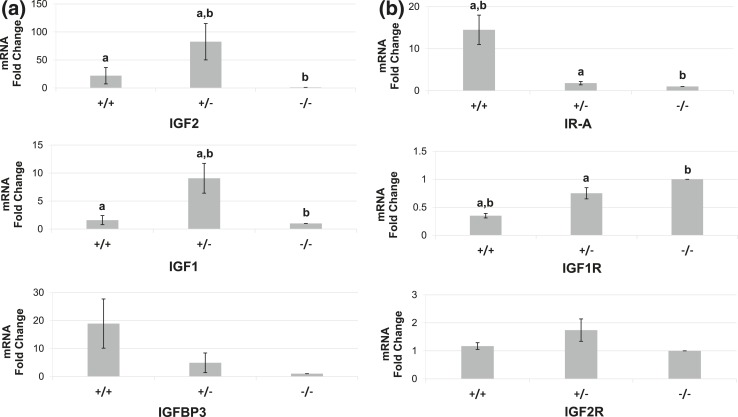

Microarray profiling indicated overexpression of the growth factors IGF1 and IGF2 in CD34+/CD49b− cells, whereas the binding protein IGFBP3, which regulates the availability of these growth factors, was overexpressed in CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells. qRT-PCR verified the differential expression of IGF1, IGF2, IGFBP3, and the IGF receptors IGF1R, IGF2R, and IR-A [Fig. 2(a) and (b)]. IR-A was overexpressed, whereas IGF1R expression was lower, in CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells vs CD34−/CD49b− cells (15-fold and 0.4-fold, respectively; P < 0.017). IGF2R mRNA levels were not statistically different between the three populations. Given the striking differences in IGF2 mRNA levels (up to 150-fold), and the paucity of data on the biologic role of IGF2 in uterine leiomyomas, we focused on the role of IGF2 in leiomyoma cells.

Figure 2.

qRT-PCR validation of microarray results in the three leiomyoma cell populations. (a) Compared with CD34−/CD49b− (−/−) cells, IGF2 and IGF1 were overexpressed in CD34+/CD49b− (+/−) cells (82.6-fold and 9.1-fold, respectively; P < 0.017) and IGFBP3 was overexpressed in CD34+/CD49b+ (+/+) cells (18.9-fold; P = 0.08). (b) qRT-PCR of IGF receptors. Compared with −/− cells, IR-A mRNA levels were higher in +/+ cells (14.5-fold; P = 0.005), and IGF1R mRNA levels were lower in +/+ cells (0.35-fold; P = 0.0003). There were no significant differences in IGF2R expression between the three populations. Lowercase letters denote statistically significant differences between bars bearing a given letter within each graph (P < 0.017). Note the differences in scale for fold change between graphs.

IGF2 increases proliferation in uterine leiomyoma cells, but does not affect apoptosis

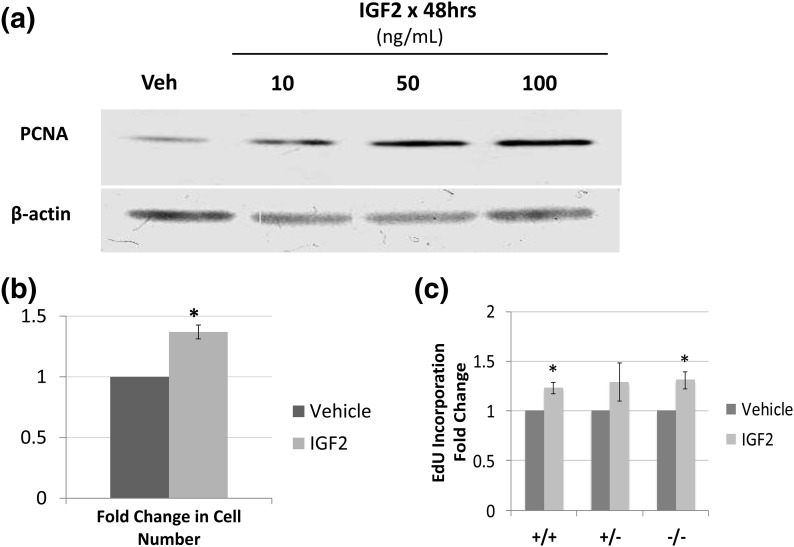

We determined the basic biologic functions of IGF2 in uterine leiomyoma by culturing primary leiomyoma cells for 48 hours with vehicle vs IGF2. Immunoblot analysis showed a dose-dependent increase in levels of the proproliferation protein PCNA [Fig. 3(a)]. IGF2 had no effect on the levels of the antiapoptotic proteins BCL2 or BCLXL (data not shown). Cell count increased 1.37-fold (P < 0.001) after overnight culture in rolling suspension with 100 ng/mL IGF2 compared with vehicle [Fig. 3(b)]. When leiomyoma cells were sorted on the basis of CD34 and CD49b expression and then treated with vehicle or IGF2, the rate of EdU incorporation into DNA, a measure of proliferation, increased in all three populations by approximately 20% to 30% compared with vehicle [Fig. 3(c)], but the increase was statistically significant only in the CD34+/CD49b+ and CD34−/CD49b− cells (23% and 31%, respectively; P < 0.05). CD34+/CD49b+ cells also had a higher percentage of proliferating cells than either CD34+/CD49b− or CD34−/CD49b− cells, regardless of treatment (9.9%, 7.7%, and 5.7% proliferating cells, respectively; P < 0.05). Our findings suggest that IGF2 increases leiomyoma cell number by inducing the proliferation of specific cell populations.

Figure 3.

(a) Representative immunoblot showing an IGF2 dose-dependent increase in PCNA . (b) Increase in cell number based on cell counting after treatment with vehicle or 100 ng/mL IGF2 (1.36-fold; *P < 0.001). (c) Percent of proliferating cells as measured by EdU incorporation within each population after treatment with vehicle or 100 ng/mL IGF2. With IGF2 treatment, proliferation increased 23% in CD34+/CD49b+ (+/+) cells, 29% in CD34+/CD49b− (+/−) cells, and 34% in CD34−/CD49b− (−/−) cells, but the change in +/− cells was not statistically significant (*P < 0.05 compared with vehicle). Veh, vehicle.

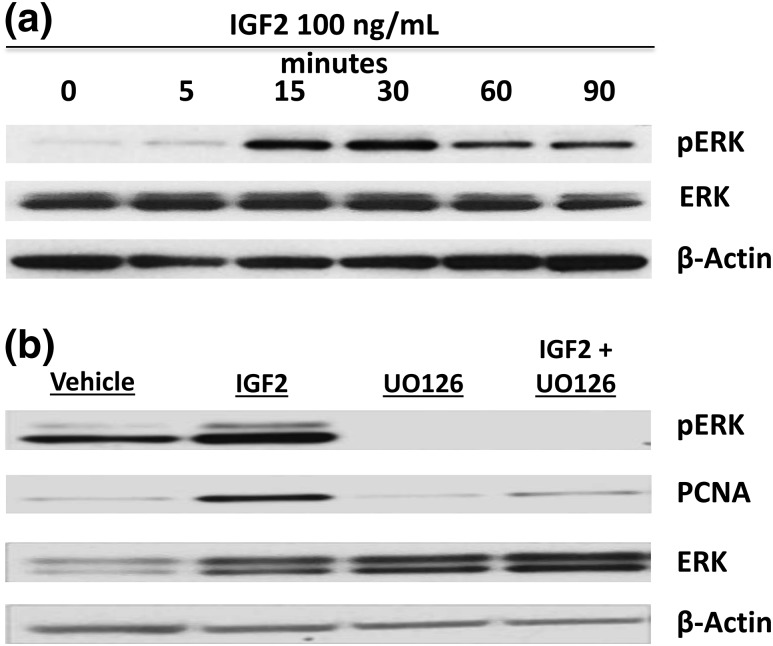

IGF2 activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK pathway in leiomyoma cells

To determine the downstream biologic effects of IGF2 in leiomyoma cells, we performed a time course study in which unsorted leiomyoma cells were incubated with 100 ng/mL IGF2 for 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 90 minutes. IGF2 activated the mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK pathway, with ERK phosphorylation observed as soon as 15 minutes, detected using antibodies that recognize both ERK1 and ERK2 [Fig. 4(a)]. Blockage of the ERK pathway with a 2-hour preincubation with the inhibitor compound U0126 strikingly decreased the levels of the proproliferation protein PCNA in IGF2-treated leiomyoma cells, compared with IGF2-treated cells without mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibition [Fig. 4(b)]. Representative blots are shown. Each experiment was reproduced in unsorted leiomyoma cells from a total of three different patients.

Figure 4.

IGF2 activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK pathway in leiomyoma cells. (a) Representative immunoblot after a time course treatment of leiomyoma cells with IGF2 100 ng/mL. Activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway via ERK phosphorylation (pERK) is seen in a mixed population of leiomyoma cells within 15 minutes of treatment. (b) Representative immunoblot of the decrease in IGF2-induced proproliferation protein PCNA after inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (upstream of ERK) with 10 µM U0126.

Discussion

We demonstrated that the three populations of leiomyoma cells, separated on the basis of CD34 and CD49b expression, are molecularly distinct. Our findings suggest that CD34+/CD49b− cells represent an intermediary population during the differentiation of CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells to the mature CD34−/CD49b− population that comprises the bulk of the tumor. IGF2 plays a critical role in leiomyoma pathogenesis and may mediate a paracrine interaction between CD34+/CD49b− cells (with high IGF2 expression) and CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells (with high IR-A expression) within leiomyoma. IGF2 increases proliferation of leiomyoma cells, particularly the CD34+/CD49b+ stem cells, likely via the ERK pathway. Thus, we uncovered a key signaling system that supports leiomyoma stem cell proliferation and growth and may contribute to leiomyoma pathogenesis. The IGF2 pathway may thus represent a potential target for novel therapies to reduce the growth of existing leiomyoma or prevent the growth of new tumors.

Although microarray studies have consistently shown IGF2 to be overexpressed in leiomyoma compared with myometrium (10), there are relatively few data in the literature on the role of IGF2 in leiomyoma pathogenesis. In 1993, Giudice et al. (11) reported that estradiol action on the growth of leiomyoma was mediated by IGF1, but not IGF2, and that IGF2 expression was unaffected by hormonal status. Shortly thereafter, Strawn et al. (12) reported that IGF1, but not IGF2, increased leiomyoma proliferation. These disparate findings may be explained by the differences in scale between our study and previous studies. Whereas previous studies examined the global effects of steroid hormone and IGF on unsorted leiomyoma cells, our research focused on the role of IGF in stem cells compared with more mature cell populations within leiomyoma tissue.

Other studies have similarly shown that IGF1 increases both survival and proliferation and decreases apoptosis in leiomyoma (13–15), but evidence suggests that IGF1 and IGF2 signal through different pathways (16), and data on the effects of IGF1 may not be applicable to IGF2. Leiomyoma tissue from women treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist secretes less IGF1 and IGF2 compared with leiomyoma tissue from women without treatment (17), suggesting that there may be some steroid hormone–mediated regulation of IGF2 expression. Most recently, Di Tommaso et al. (18) reported that IGF2 overexpression in leiomyoma is highly correlated with missense mutations in the mediator complex subunit 12 (MED12) gene, suggesting that there are possibly separate and independent pathways of leiomyoma pathogenesis. Although this study did not determine the MED12 status of the included leiomyoma tissue, the effects of IGF2 in leiomyoma tissue harboring MED12 mutations vs tumors without MED12 mutations could be an interesting area of future study.

Although there is a paucity of data on the role of IGF2 or IR-A in leiomyoma, their involvement in cancer and stem cell biology has been well established. Cancer cells overexpress IR-A, with increased affinity for IGF2, autocrine production of IGF2, and preferential activation of the ERK pathway (19, 20). Several malignancies also overexpress IGF2, including colorectal, adrenal, thyroid, prostate, breast and ovarian carcinomas, leukemia, and sarcomas. Elevated IGF2 production is often correlated with poorer prognosis (19, 20). Moreover, IGF2 produced by human embryonic stem cell–derived fibroblasts is necessary for self-renewal and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells, and IR-A is overexpressed in both cancer and stem cells (19, 20). It is possible that embryonic stem cell–derived fibroblasts are analogous to the CD34+/CD49b− (intermediary) leiomyoma cell population in our study; this will be explored further in the future. IGF2 acts through IR-A in promoting self-renewal and stemness of neural stem cells (21). Also consistent with our data that show higher expression of IR-A in the leiomyoma stem cell population, IR-A is significantly overexpressed in neural stem cells compared with neurons, whereas IGF1R is significantly underexpressed (21). Thus, with respect to IGF signaling, the leiomyoma stem and intermediary cell populations seem to exhibit a paracrine interaction pattern consistent with other tissues.

There are some limitations to our study. The use of primary tissues is a strength in that the experiments are closer to in vivo conditions than those using cell lines, but there is also greater sample-to-sample variability inherent to individual patients, making statistical analysis challenging. We overcame this challenge by sampling a relatively large number of patients (n = 8) and using a large total sample size (n = 24) for microarray profiling, and by electing to use tissues from only African American women to minimize race-dependent variation. Additionally, given the small percentage of stem cells in leiomyoma tissue, we were limited to using large tumors to obtain sufficient cell numbers to perform our experiments. This limited our ability to restrict included tissue by patient age or phase of menstrual cycle, although all included subjects were premenopausal and no subjects had received any hormonal or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist or antagonist treatments in the prior 6 months. The ability of IGF2 to induce leiomyoma proliferation was decreased significantly by blocking the ERK pathway; however, the role of IR-A remains to be demonstrated mechanistically. Future studies will focus on disrupting IR-A to address this question. Finally, we are still refining our methods for long-term culture of stem cells and maintenance of their dedifferentiated status, so our experiments were limited to short culture periods after sorting the leiomyoma cells into the three populations. As methods for culturing and studying leiomyoma stem cells evolve, we should be able to study the pathways involved in their function in greater detail.

Overall, this study presents a genome-wide comparison between three populations of leiomyoma cells, including leiomyoma stem cells, as well as evidence on the importance of IGF2 signaling and IR-A in leiomyoma stem cells and tumor growth. The IGF2 system is likely one of the paracrine pathways involved in leiomyoma stem cell function. Future studies should use this microarray data to further delineate the role of the three populations in leiomyoma pathogenesis and interaction between the populations. Additionally, because IGF2 is primarily regulated by imprinting, methylation studies may help explain some of the differences in expression between cell types. Given that IGF2 plays a relatively minor role in normal adult physiology (20), it is an attractive therapeutic target. There are already multiple studies underway investigating strategies to target IGF2 expression or function as anticancer treatment (20). It would be interesting to investigate whether any of these potential therapeutics are compatible with intrauterine delivery to more precisely target leiomyomas. Increasing our understanding of leiomyoma stem cell pathophysiology is important because the ability to target pathways necessary for stem cell action may lead to the development of treatments that can not only shrink existing leiomyomas, but also prevent the development of new tumors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Northwestern University Flow Cytometry Facility, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Grant No. CA060553. Microarray services were performed at the Northwestern University Genomics Core Facility.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant P01-HD057877 (S.E.B.) and American Society for Reproductive Medicine In-Training Grant in Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (M.B.M.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- IGF

- insulinlike growth factor

- IGF1R

- IGF1 receptor

- IGF2R

- IGF2 receptor

- IGFBP3

- IGF binding protein 3

- IR-A

- insulin receptor A

- MED12

- mediator complex subunit 12

- mRNA

- messenger RNA

- TBS

- Tris-buffered saline.

References

- 1.Bulun SE. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(14):1344–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moravek MB, Yin P, Ono M, Coon JS V, Dyson MT, Navarro A, Marsh EE, Chakravarti D, Kim JJ, Wei JJ, Bulun SE. Ovarian steroids, stem cells and uterine leiomyoma: therapeutic implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ono M, Qiang W, Serna VA, Yin P, Coon JS V, Navarro A, Monsivais D, Kakinuma T, Dyson M, Druschitz S, Unno K, Kurita T, Bulun SE. Role of stem cells in human uterine leiomyoma growth. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mas A, Cervelló I, Gil-Sanchis C, Faus A, Ferro J, Pellicer A, Simón C. Identification and characterization of the human leiomyoma side population as putative tumor-initiating cells. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):741–751.e6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Golebiewska A, Brons NH, Bjerkvig R, Niclou SP. Critical appraisal of the side population assay in stem cell and cancer stem cell research. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(2):136–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin P, Ono M, Moravek MB, Coon JS V, Navarro A, Monsivais D, Dyson MT, Druschitz SA, Malpani SS, Serna VA, Qiang W, Chakravarti D, Kim JJ, Bulun SE. Human uterine leiomyoma stem/progenitor cells expressing CD34 and CD49b initiate tumors in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(4):E601–E606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ono M, Yin P, Navarro A, Moravek MB, Coon JS V, Druschitz SA, Serna VA, Qiang W, Brooks DC, Malpani SS, Ma J, Ercan CM, Mittal N, Monsivais D, Dyson MT, Yemelyanov A, Maruyama T, Chakravarti D, Kim JJ, Kurita T, Gottardi CJ, Bulun SE. Paracrine activation of WNT/β-catenin pathway in uterine leiomyoma stem cells promotes tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(42):17053–17058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton JL, Unno K, Caraveo M, Lu Z, Kim JJ. Increased AKT or MEK1/2 activity influences progesterone receptor levels and localization in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(12):E1871–E1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikawa H, Fenkci V, Marsh EE, Yin P, Chen D, Cheng YH, Reisterd S, Lin Z, Bulun SE. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta regulates aromatase expression via multiple and novel cis-regulatory sequences in uterine leiomyoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):981–991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arslan AA, Gold LI, Mittal K, Suen TC, Belitskaya-Levy I, Tang MS, Toniolo P. Gene expression studies provide clues to the pathogenesis of uterine leiomyoma: new evidence and a systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):852–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giudice LC, Irwin JC, Dsupin BA, Pannier EM, Jin IH, Vu TH, Hoffman AR. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF), IGF binding protein (IGFBP), and IGF receptor gene expression and IGFBP synthesis in human uterine leiomyomata. Hum Reprod. 1993;8(11):1796–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strawn EY Jr, Novy MJ, Burry KA, Bethea CL. Insulin-like growth factor I promotes leiomyoma cell growth in vitro. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(6):1837–1843. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.van der Ven LT, Gloudemans T, Roholl PJ, van Buul-Offers SC, Bladergroen BA, Welters MJ, Sussenbach JS, den Otter W. Growth advantage of human leiomyoma cells compared to normal smooth-muscle cells due to enhanced sensitivity toward insulin-like growth factor I. Int J Cancer. 1994;59(3):427–434. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Maruo T, Matsuo H, Shimomura Y, Kurachi O, Gao Z, Nakago S, Yamada T, Chen W, Wang J. Effects of progesterone on growth factor expression in human uterine leiomyoma. Steroids. 2003;68(10–13):817–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciarmela P, Islam MS, Reis FM, Gray PC, Bloise E, Petraglia F, Vale W, Castellucci M. Growth factors and myometrium: biological effects in uterine fibroid and possible clinical implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(6):772–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng L, Wen Y, Han Y, Wei A, Shi G, Mizuguchi M, Lee P, Hernando E, Mittal K, Wei JJ. Expression of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF signaling: molecular complexity in uterine leiomyomas. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2664–2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rein MS, Friedman AJ, Pandian MR, Heffner LJ. The secretion of insulin-like growth factors I and II by explant cultures of fibroids and myometrium from women treated with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76(3 Pt 1):388–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Tommaso S, Tinelli A, Malvasi A, Massari S. Missense mutations in exon 2 of the MED12 gene are involved in IGF-2 overexpression in uterine leiomyoma. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20(10):1009–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belfiore A, Malaguarnera R. Insulin receptor and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2011;18(4):R125–R147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livingstone C. IGF2 and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(6):R321–R339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziegler AN, Schneider JS, Qin M, Tyler WA, Pintar JE, Fraidenraich D, Wood TL, Levison SW. IGF-II promotes stemness of neural restricted precursors. Stem Cells. 2012;30(6):1265–1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]