Abstract

The biosynthetic pathway of the branched-chain amino acids is essential for Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth and survival. We report here the kinetic and chemical mechanism of the pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent branched-chain aminotransferase, IlvE, from M. tuberculosis (MtIlvE). This enzyme is responsible for the final step of the synthesis of the branched-chain amino acids isoleucine, leucine, and valine. As seen in other aminotransferases, MtIlvE displays a ping-pong kinetic mechanism. pK values were identified from the pH dependence on V as well as V/K, indicating that the phosphate ester of the PLP cofactor, and the α-amino group from L-glutamate and the active site Lys204, play roles in acid–base catalysis and binding, respectively. An intrinsic primary kinetic isotope effect was identified for the α-C–H bond cleavage of L-glutamate. Large solvent kinetic isotope effect values for the ping and pong half-reactions were also identified. The absence of a quininoid intermediate in combination with the Dkobs in our multiple kinetic isotope effects under single-turnover conditions suggests a concerted type of mechanism. The deprotonation of C2 of L-glutamate and the protonation of C4′ of the PLP cofactor happen synchronously in the ping half-reaction. A chemical mechanism is proposed on the basis of the results obtained here.

Graphical Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of human tuberculosis (TB), has acquired ways to overcome the once successful therapeutic regimen composed of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide. The bacteria have evolved to become multidrug resistant (MDR-TB), extensively drug resistant (XDR-TB), and in some cases totally drug resistant (TDR-TB).1,2 In 2014, approximately 190000 of 480000 new and previously infected patients died due to MDR-TB infection.3

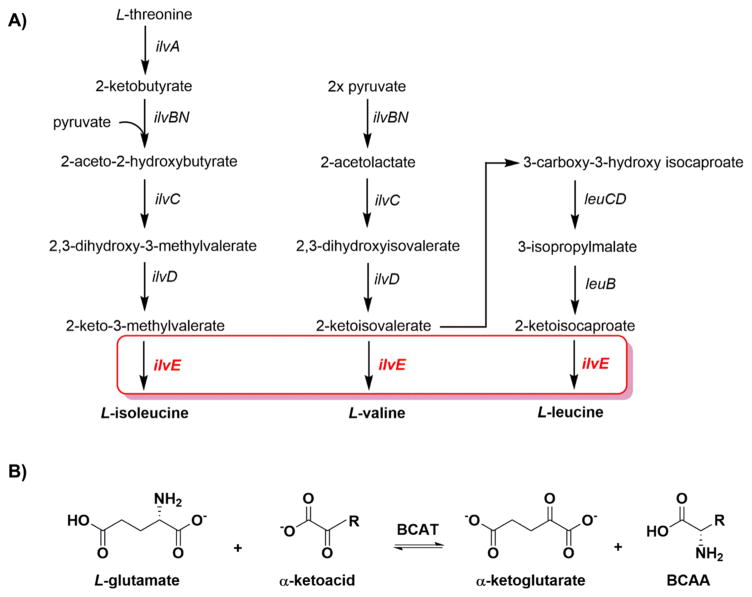

Enzymes belonging to the biosynthetic pathway of the branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) isoleucine, leucine, and valine have been identified as being essential in M. tuberculosis. A strain in which the leuCD genes are deleted is extensively attenuated for growth in mice,4 yet when present in monkeys, the leuCD knockout strain provides a protective response against a secondary infection with wild-type M. tuberculosis.5 In addition, high-density mutagenesis studies found that the branched-chain aminotransferase gene, IlvE, is essential for the growth and survival of M. tuberculosis.6,7 In prokaryotes, branched-chain aminotransferases (BCAT) catalyze the final step of the synthesis of all three BCAAs (Scheme 1).8,9 The biosynthetic pathway of BCAAs is absent in higher eukaryotes; however, the first step of catabolism of these amino acids requires a transamination that is catalyzed by a BCAT.9,10 In the biosynthetic pathway, BCAT transfers the amino group of L-glutamate to the α-keto acid form of the respective amino acid to be synthesized (Scheme 1). This reaction is reversible and depends on the covalently bound pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP) cofactor linked through a Schiff base with an active site lysine residue.10,11

Scheme 1.

(A) Biosynthetic Pathway of the Branched-Chain Amino Acids in M. tuberculosis (in which MtIlvE catalyzes the final step in the synthesis of all three branched-chain amino acids) and (B) General View of the Reaction Catalyzed by BCATs, Including MtIlvE

PLP-containing enzymes are involved in numerous biosynthetic and catabolic pathways. They link nitrogen and carbon metabolism and have been considered as potential drug targets.12 Among the PLP-dependent enzymes already identified as drug targets, we highlight the Trypanosoma brucei ornithine decarboxylase, target of α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), which is used in the treatment of African sleeping sickness.13 Of particular relevance to M. tuberculosis is the activity of D-cycloserine (D-CS), which has been used almost exclusively as a second-line drug for the treatment of MDR-TB. This natural product isolated from Streptomyces species acts by irreversibly inhibiting the activity of the PLP-dependent alanine racemase that converts L-alanine to D-alanine. In addition, D-CS acts by inhibiting the enzyme D-alanine-D-alanine ligase.14 Both enzymes are involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis and are essential for the growth and survival of M. tuberculosis.14–16 Nevertheless, low-level resistance has already been identified.17 The inhibitory mechanism of these drugs is the result of a mechanism-based inhibition caused by partial catalysis where a stable intermediate is formed, thus creating an inactive protein–PLP–inhibitor complex.18,19 In addition, humans contain two BCATs: a cytosolic (hBCATc) and a mitochondrial BCAT (hBCATm) that share approximately 58% sequence identity. However, minor differences in their structures allow Gabapentin, a Food and Drug Administration-approved anti-epileptic drug, to bind and inhibit the cytosolic form while having no activity against the mitochondrial enzyme.20 hBCATc is predominantly expressed in the brain and is involved in the production of L-glutamate, an important excitatory neurotransmitter.18 In contrast, hBCATm is expressed primarily in skeletal muscle where hBCATm is used to generate precursors for protein synthesis and the Krebs cycle (α-ketoglutarate).18

In M. tuberculosis H37Rv, the PLP-dependent BCAT is encoded by the Rv2210c gene and annotated as IlvE.21 M. tuberculosis IlvE (MtIlvE) is a 40 kDa protein and exists in solution as a homodimer.8 The three-dimensional structure reveals that each monomer is tethered by a substrate specificity loop to its partner molecule.8 The sequence of hBCATm is 30% identical with that of MtIlvE; nonetheless, unique features can be identified in the tuberculosis enzyme.8 The most interesting difference between MtIlvE and other known orthologous BCATs is the presence of two neighboring cysteine residues at the interface of the homodimer.8 Under oxidative conditions, such as the ones found in the phagosome, these cysteine residues may play an important and unique role by forming an intersubunit disulfide bond that may provide additional stability to the dimeric protein.8

Previous studies have found MtIlvE to be active in the presence of the three BCAAs and L-glutamate.9,22 Additionally, it has been shown that MtIlvE is involved in the last step of the methionine salvage pathway, where it catalyzes the transfer of an amino group from any of the BCAAs to α-keto-γ-methylthiobutyric acid.9 Inhibition of MtIlvE as well as growth inhibition of M. tuberculosis has been demonstrated with aminooxy compounds (or O-hydroxylamines).9 Therefore, the inhibition of this enzyme disrupts not only BCAA biosynthesis but also the major methionine salvage pathway. The TB enzyme is also uniquely active with phenylalanine, and to a lesser extent with tryptophan and tyrosine.9 This broad substrate specificity displayed by MtIlvE may be an important difference between human and mycobacterial BCAT and may potentially be exploited in the development of specific inhibitors.

In this work, we report the kinetic and biochemical characterization of the anabolic reaction catalyzed by MtIlvE, using pH–rate profiles as well as steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetic isotope effects. On the basis of our findings, we propose a mechanism that is, to the best of our knowledge, the first detailed mechanistic analysis of a BCAT from any organism.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

All chemicals and reagents used were of analytical and/or reagent grade from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals. Deuterium oxide (D2O, 99.9 atom % D) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories.

Expression and Purification

MtIlvE was expressed and purified as previously described.8 The protein concentration was measured by using a theoretical extinction coefficient value (ε280) of 56505 M−1 cm−1.

Activity Assay and Initial Velocity Experiments

Reaction rates were measured spectrophotometrically (Shimadzu UV-2450) by coupling the MtIlvE-catalyzed reaction to L-glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), in the presence of excess reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and ammonia. The activity was observed as the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm (ε340 = 6220 M−1 cm−1) upon NADH oxidation and α-ketoglutarate utilization. All measurements were performed in duplicate, at 25 °C using 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) (buffer A), unless stated otherwise. The reactions were started with the addition of 40 nM MtIlvE and followed for 1–2 min. Individual substrate saturation kinetic data were fitted to eq 1

| (1) |

where V is the maximal velocity, A is substrate concentration, and K is Michaelis–Michaelis constant KM. Initial velocity studies were conducted by fixing either L-glutamate or α-ketoisocaproate at five different concentrations while varying the concentrations of the other. Besides the natural branched-chain α-keto acids, α-ketoisocaproate, α-ketoisovalerate, and α-ketomethyl-oxo-pentanoic acid, several other α-keto acids, such as butyric acid, pyruvate, α-keto-phenylpyruvic acid, and α-keto-γ-methylthiobutyric acid, were tested. Equation 2 was used to fit the parallel initial velocity pattern:

| (2) |

where A and B are the concentrations of substrates and Ka and Kb are the Michaelis–Menten constants for the substrates.

pH–Rate Profiles

pH–rate profile experiments were conducted by using a mixed buffer (100 mM TAPS-MOPS) and varying the pH from 6.0 to 9.5 at 25 °C. We limited this investigation to pH 9.5 because of the instability of the coupling enzyme, GDH, under basic pH conditions.23 In these experiments, initial velocity patterns were performed within the chosen pH range in 0.5 unit increments. The stability of MtIlvE at each pH was tested by incubating it in the desired buffer and then conducting a standard assay. pH–rate profiles were fitted to eq 3 or 4

| (3) |

| (4) |

where c is the pH-independent plateau value and y is the rate.

Deuterium Exchange

[2-2H]Glutamate was enzymatically synthesized by using MtIlvE-catalyzed reaction in the presence of 99% deuterated buffer A. Briefly, 50 mM L-glutamate and 50 μM α-ketoisocaproate were dissolved in 10 mL of 50 mM Na2PO4− buffer at pH 7.5, frozen, and lyophilized. The freeze-dried product was then diluted in 5 mL of D2O, frozen, and lyophilized until the H2O had been completely removed. The final product was redissolved in 10 mL of D2O, and the final MtIlvE concentration of 100 μM previously buffer exchanged (buffer A in D2O) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated overnight at room temperature. The enzyme was removed from the reaction by centrifugal filtration using an Amicon device (30K molecular weight cutoff) and passed through a Dowex column (formate form) using a gradient of 0 to 6 N formic acid. Fractions containing [2-2H]glutamate were identified by ninhydrin staining using a TLC plate. The residual formic acid was removed by rotary evaporation. The progression of the reaction was followed by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), which was used to evaluate the percentage of deuteration of [2-2H]glutamate. A GDH-based assay coupled to diaphorase and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was used to measure the concentrations of L-glutamate and [2-2H]glutamate for primary and multiple kinetic isotope effect (KIE) experiments.

Kinetic Isotope Effects (KIEs)

Primary KIE studies were performed through a typical Michaelis–Menten experiment using either L-glutamate or [2-2H]glutamate, and one of the branched-chain α-keto acids, or α-keto-phenylpyruvic acid, as substrates. A pH dependence of the primary KIE was performed by using the same mixed buffer used for pH profile experiments. Solvent KIEs were determined using either H2O or D2O (95%) by determining initial velocities in the presence of a fixed amount of one substrate while varying the other. To mimic the viscosity effect caused by D2O (nrel = 1.24), the reaction rates using H2O and 9% glycerol were compared.24 Multiple KIEs were measured by performing primary KIEs in D2O buffer A. The kinetic isotope effect data were fitted to eq 5

| (5) |

where V is the maximal velocity, A is the concentration of [2-2H]glutamate and/or L-glutamate, Fi is the fraction of isotope (0 or 0.95–1), EV/K is the effect on kcat/KM (−1), and EV is the effect on kcat (−1).

Pre-Steady-State KIEs

The pre-steady-state analysis was conducted by using an SX-20 stopped-flow spectrophotometer (Applied Photophysics). The dead time of the instrument is 3 ms. To prepare the PLP form of the enzyme, 100 μM MtIlvE was incubated with 10 mM α-ketoisocaproate for 1 h under regular assay conditions. The PMP form of the enzyme was prepared by incubating MtIlvE with 20 mM L-glutamate for the same amount of time. The reaction mixtures in both cases were buffer exchanged 10 times by centrifugal filtration using an Amicon device (10K molecular weight cutoff) at 4 °C for 15 min at 4000 rpm. A UV–visible absorbance spectrum was determined to confirm the presence of the external aldimine or PMP form of the enzyme as well as to calculate its concentration. Titrations of the PLP and PMP forms of the enzymes were used to calculate the extinction coefficient under our experimental conditions and yielded an ε415_PLP of 6900 M−1 cm−1 and an ε330_PMP of 12500 M−1 cm−1 (Figure S1). A 1:1 MtIlvE:PLP or MtIlvE:PMP ratio was used to perform the experiments. Scans were typically collected at exponential intermissions between 1 and 5 s to reach a plateau. The absorbance range monitored was between 300 and 550 nm. All experiments were carried out using MtIlvE at 26 μM (monomer concentration) after mixing, on regular buffer A or deuterated buffer A at room temperature.25 When the experiments were carried out in D2O, the enzyme’s buffer was exchanged with D2O buffer A, and the reactants were dissolved in the same D2O buffer A, lyophilized, and redissolved in D2O buffer A. Single-turnover primary KIEs were examined by comparing the rates of the reaction in the presence of increasing concentrations of either L-glutamate or [2-2H]glutamate. Solvent single-turnover KIEs were verified in the presence of increasing concentrations of L-glutamate (first half-reaction) and α-ketoisocaproate or α-ketoisovalerate (second half-reaction) in either H2O or D2O buffer A. Multiple single-turnover KIEs were determined in the presence of L-glutamate or [2-2H]glutamate in D2O buffer A. Pre-steady-state data were fitted to eq 6, which represents a single-exponential curve

| (6) |

where A1 is the amplitude, y0 is the y offset, and k is the observed rate constant. The rates observed with different concentrations of substrates (kobs) were replotted as a function of substrate concentration and fitted to eq 5.

Data Analysis

All data were fitted accordingly to the proper equation using Sigma Plot 11.0 (SPSS, Inc.) or GraphPad Prism 6.07 nonlinear regression function. The points represent the means of experimental replicates, and the error bars represent the standard deviation. The solid lines are the results obtained after fitting to the indicated equation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

MtIlvE Displays a Ping-Pong Mechanism

The steady-state kinetic parameters for the amino donor, L-glutamate, and various α-keto acid cosubstrates are listed in Table 1. The enzyme is extremely specific for L-glutamate as the amino donor in the direction of branched-chain amino acid synthesis, and L-aspartate has no activity with the enzyme. The KM value for L-glutamate is, however, quite high, presumably reflecting the high intracellular concentration of L-glutamate in the cell. However, in a previous study of the reverse reaction, L-glutamate, L-leucine, L-valine, L-isoleucine, and L-phenylalanine were all capable of donating their amino group to α-keto-γ-methylthiobutyric acid, the precursor to L-methionine,9 suggesting broader specificity in this direction. When the selectivity of MtIlvE for α-keto acid substrates was interrogated, it is clear that the precursors to the branched-chain amino acids L-leucine, L-valine, and L-isoleucine were nearly equally good substrates, with 100–200 μM KM values and nearly equivalent V values. α-Keto-phenylpyruvic acid was a 20-fold poorer substrate, as was α-keto-γ-methylthiobutyric acid, which exhibited a very high KM value but a very robust V value, equivalent to those of the best branched-chain α-keto acid substrates.

Table 1.

Summary of MtIlvE Michaelis–Menten Constants in the Presence of Different α-Keto Acids and L-Glutamatea

| substrate | KM (×10−3 M) | V (s−1) | V/K (×104 M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-glutamate | 1.30 ± 0.2 | 8.9 ± 0.4 | 0.7 |

| α-keto-methyl-oxopentanoic acid | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 6.2 |

| α-ketoisocaproate | 0.24 ± 0.03 | 9.1 ± 0.4 | 3.8 |

| α-ketoisovalerate | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 3.6 |

| α-keto-phenylpyruvic acid | 0.64 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.04 | 0.2 |

| α-keto-γ-methylthiobutyric acid | 6.07 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.1 | 0.2 |

V is the constant for the catalytic turnover of the enzyme. K is the substrate concentration necessary for the enzyme to reach half of its Vmax. V/K is the substrate specificity.

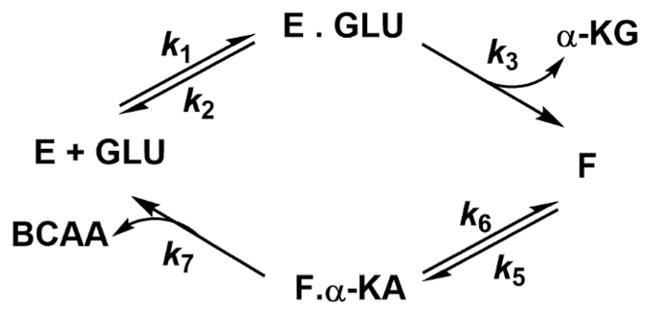

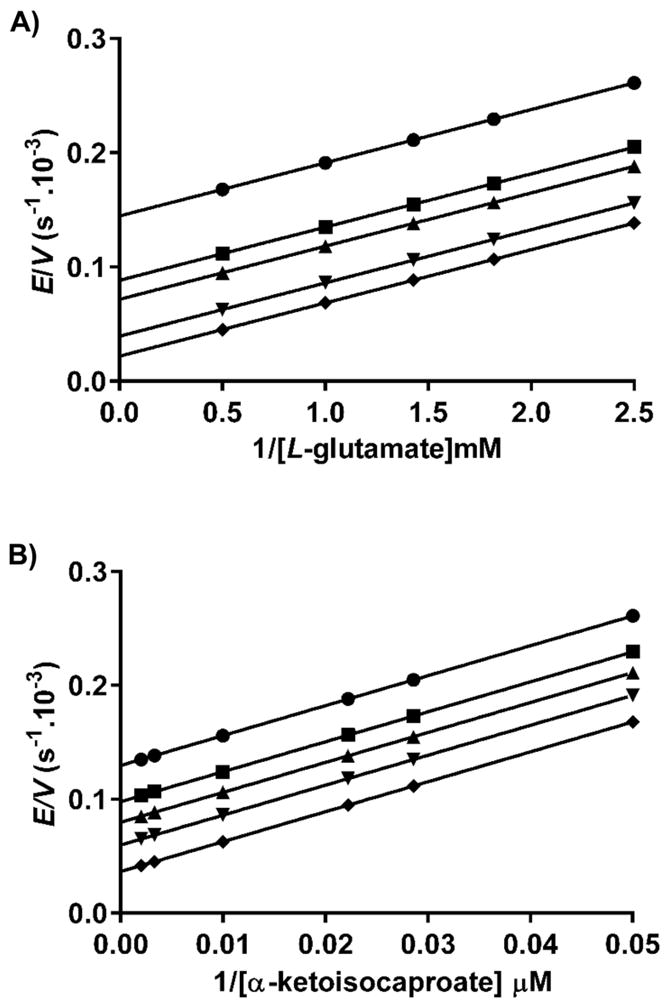

A hallmark of aminotransferases is their signature ping-pong kinetic mechanism, with two separate half-reactions involving two stable enzyme forms, the E–PLP and E–PMP complexes. This is also the case with MtIlvE (Scheme 2), where L-glutamate reacts with the E–PLP form of the enzyme, resulting in the formation of the first product, α-ketoglutarate, and the E–PMP form of the enzyme. The second substrate, the α-keto acid precursor of the branched-chain amino acids, then binds to the E–PMP form of the enzyme, which then results in the formation of the corresponding amino acid. Via variation of the concentration of the amino donor at several fixed concentrations of the α-keto acid acceptor, a series of parallel lines are observed in the reciprocal initial velocity plot (Figure 1). A similar plot is observed when varying the concentration of the α-keto acid acceptor at several fixed concentrations of the amino acid donor. This confirms the steady-state mechanism as being bi-bi ping-pong. Because of the different spectroscopic properties of the E–PLP and E–PMP complexes, these two half-reactions can also be observed without steady-state turnover. When the E–PLP form of the enzyme is incubated with L-glutamate, the absorbance at 415 nm due to Schiff base-ligated PLP decreases with time, while the peak at 330 nm, due to enzyme-bound PMP, increases (Figure S2). If the α-keto acid substrate is incubated with the E–PMP form of the enzyme, the opposite changes are observed.

Scheme 2. Kinetic Mechanism of the Transamination Catalyzed by MtIlvEa.

aE and F represent the two stable forms of the enzyme, PLP and PMP, respectively.

Figure 1.

Initial velocity pattern showing a series of parallel lines characteristic of a ping-pong kinetic mechanism. (A) Glutamate as the variable substrate and fixed α-ketoisocaproate concentrations of 20 (●), 35 (■), 45 (▲), 100 (▼), and 300 μM (◆). (B) α-Ketoisocaproate as the variable substrate and fixed glutamate concentrations of 0.4 (●), 0.5 (■), 0.7 (▲), 1 (▼), and 2 mM (◆).

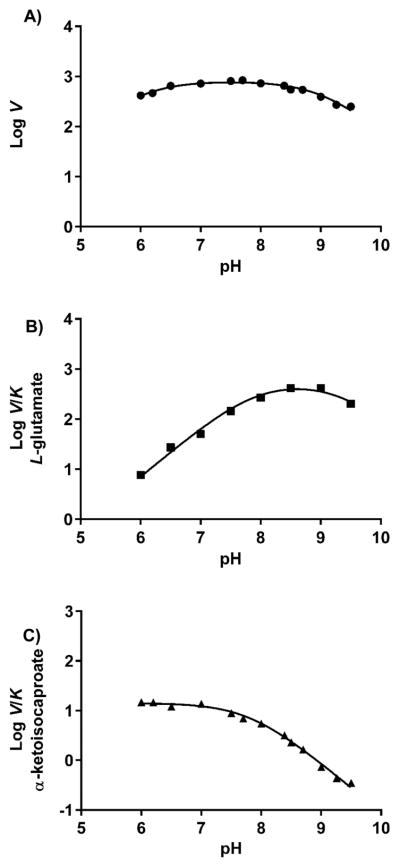

pH Dependence of Kinetic Parameters

At a saturating concentration of α-ketoisocaproate and variable concentrations of L-glutamate, the V and V/K values were determined at pH values between 6 and 9.5. Because of the coupling enzyme used to measure the reaction, the assay was reliable only in this pH range. The pH dependence of V is negligible in this pH range, showing only a slight reduction at the pH extremes (Figure 2A). However, a fit of the data (solid line through data points) to eq 3 yielded pK values of ~6 and ~9. The pK of 6 has been assigned to the phosphate ester of the PLP cofactor in dialkylglycine decarboxylase26 and D-serine dehydratase.27 The negative charge on the phosphate may assist in stabilizing the formation of the protonated external aldimine (Scheme 3). The pK of 9 has been proposed to be a possible conformational change in the enzyme or the ε-amino group of the active site lysine.26 The pH dependence of V is a composite of ionizable groups involved in both the ping and pong reactions, and thus, absolute assignments to individual groups are difficult to make.

Figure 2.

pH dependence on kcat (●), kcat/KM_L-gutamate (■), and kcat/KM_α-ketoisocaproate (▲) for MtIlvE. The lines represent fits to eqs 3 and 4.

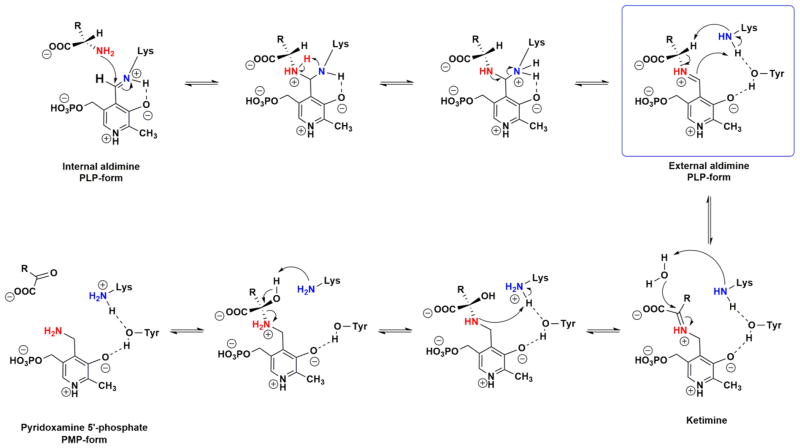

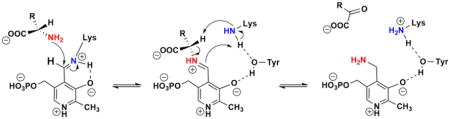

Scheme 3. Chemical Mechanism Proposed for the Reaction Catalyzed by MtIlvEa.

aThe blue box corresponds to a concerted mechanism, showing a single transition state in the first half-reaction.

The pH dependence of V/KL-glutamate is bell-shaped with pK values of 7.8 ± 0.04 and 9.3 ± 0.02 (Figure 2B). These represent ionizations of either the substrate or the free enzyme, in this case the E–PLP form. The group whose pK is observed at 7.8, which must be deprotonated for efficient binding, is unclear at this time. Previous studies of dialkylglycine decarboxylase assigned this group as the carboxyl side chain of Glu210 that interacts with the pyridinium nitrogen of bound PLP.26 The pK observed at 9.3, which must be protonated, is most likely to be the α-amino group of L-glutamate. On the other hand, the pH dependence of log V/Kα-ketoisocaproate represents potential ionizations of groups on the substrate or the enzyme, in this case the E–PMP form. A single pK value of 7.8 ± 0.01 is observed, reflecting a group that must be protonated for binding or catalysis (Figure 2C). It would seem unlikely that this group is the carboxylate that interacts with the pyridinium nitrogen of bound PMP, although the electronic properties of the PLP and PMP forms might influence the preferred ionization state of Glu240 in the two complexes.8 Alternatively, in the PMP complex, Lys204, in its positively charged state, is possibly interacting with the carboxylate of the incoming α-keto acid.

The α-C–H Bond Cleavage Is Partly Rate-Limiting

The magnitude of the steady-state primary deuterium kinetic isotope is determined by the magnitude of the intrinsic deuterium kinetic isotope effect on α-C–H bond cleavage and the associated commitment factor for the isotopically labeled substrate. In the case of the V/K isotope effect using [2-2H]glutamate (Figure S3), this commitment factor is the rate of the chemical step involving α-C–H bond cleavage divided by the rate of dissociation of L-glutamate from the enzyme. For a ping-pong kinetic sequence, the chemical nature of the α-keto acid cosubstrate does not influence this commitment factor. As shown in Table 2, irrespective of the cosubstrate used, DV/K[2-2H]glutamate is approximately 2 for all substrate pairs, as expected. The magnitude of the steady-state V kinetic isotope effect is also determined by the intrinsic kinetic isotope effect and a different commitment factor. The V commitment factor is the ratio of the rates of the “ping” reaction divided by the “pong” reaction and will therefore be highly dependent on the α-keto acid cosubstrate used. For the best substrate used here (α-ketoisocaproate), the DV value suggests that if the intrinsic kinetic isotope effect is 2, the ratios of the ping and pong reactions are comparable, leading to only a small reduction in DV compared to DV/K[2-2H]glutamate. On the other hand, the magnitude of DV for poor substrates, including α-keto-phenylpyruvic acid, is substantially reduced, as expected from their lower steady-state turnover rates and thus larger V commitment factor.28

Table 2.

Primary and Solvent Kinetic Isotope Effects of MtIlvE in the Presence of Fixed Concentrations of Different Substrates

| fixed substrate | DV[2-2H]glutamate | DV/K[2-2H]glutamate | D2OV | D2OV/K |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-ketoisocaproate | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| α-ketoisovalerate | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 6.7 ± 1.8 |

| α-keto-methyl-oxopentanoic acid | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

| α-keto-phenylpyruvic acid | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | – | – |

| α-keto-γ-methylthio butyric acid | – | – | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| L-glutamate varying α-ketoisocaproate | – | – | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.2 |

The experimental values of steady-state kinetic isotope effects are often smaller than the intrinsic isotope effect for the α-C–H bond cleavage reactions. There are methods that will directly determine the magnitude of the intrinsic kinetic isotope effect, including comparing deuterium and tritium kinetic isotope effects,29 and thus report on a substrate’s commitment factor. The step involving α-C–H bond cleavage can also not be rate-determining, especially in cases in which product release is slow. Finally, large commitment factors for isotopically labeled substrates are often observed. A number of methods have been employed to understand the magnitude of a substrate’s commitment factor, including the use of poorer substrates and changes in the experimental conditions. One of the most common of these is the determination of the experimental kinetic isotope effect as a function of pH. The rationale is that a substrate with a high commitment factor binds tightly to the enzyme and dissociates slowly relative to the chemical step, and these interactions may be modulated by the titration of enzyme groups responsible for these strong interactions. We measured the steady-state primary deuterium kinetic isotope effect on L-glutamate oxidation from pH 6 to 9 in 0.5 pK increments. As shown in Figure S4, there are no significant changes to either DV or DV/K[2-2H]glutamate over this pH range. Given the very high KM value for L-glutamate, the pH independence of the kinetic isotope effects is not surprising. If L-glutamate truly has no commitment, then the value of ~2 that we measured could report on the intrinsic kinetic isotope effect for α-C–H bond cleavage. The magnitude of the intrinsic isotope effect is a function of the energy barrier height for the bond cleaving reaction step. In the case of transaminases, including MtIlvE, the cleavage reaction occurs after formation of the external aldimine, and the cleavage of the α-C–H bond results in a carbanionic intermediate that is highly resonance stabilized. This hyperconjugative effect could reduce the α-C–H bond strength and reduce the magnitude of the intrinsic deuterium kinetic isotope from its classical limit of ~8 to the value we measured here experimentally.30 Steady-state kinetic isotope effects have been determined for a number of other PLP-dependent transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase and serine-glyoxylate aminotransferase),31,32 decarboxylases (dialkylglycine decarboxylase),33 and racemases (alanine racemase) 16,34 and vary considerably in magnitude.

Steady-State Solvent Kinetic Isotope Effects

Solvent kinetic isotope effects can, in favorable circumstances, report on the rate-limiting nature of proton transfers occurring in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Prior to proceeding with these experiments, we find it is important to ensure that the effects observed are not due to the higher viscosity of D2O compared to that of H2O. In the case of MtIlvE, the addition of 9% glycerol had no effect on the rate of the reaction. The reactions were performed at fixed concentrations of L-glutamate and at varying concentrations of α-keto acid cosubstrates to obtain values of D2OV/K and D2OV. We also measured the solvent kinetic isotope effects by varying the L-glutamate concentration at a fixed saturating concentration of α-ketoisocaproate. The results are listed in Table 2. In all cases, the solvent kinetic isotope effects are normal and range between 2 and 3, including those for experiments with a varying L-glutamate concentration. The exceptions are the D2OV/K and D2OV effects exhibited by α-ketoisovalerate, which are significantly higher. There are few reports of the measurement of solvent kinetic isotope effects on the reaction of α-keto acids with the E–PMP form, although a few studies have reported solvent kinetic isotope effects on the reaction of amino donors with the E–PLP form.16,26,28,34 This is probably because the chemistry of both half-reactions involves so many potential proton transfer reactions, including in the amino donor reaction: transimination, C4′ protonation, and product imine hydrolysis. There are an equal number of proton transfer reactions in the second half-reaction, making the identification of a single proton transfer as responsible for the kinetic effect extremely difficult. Finally, the D2OV effect is a composite of all of the above. We therefore hesitate to speculate about these steady-state effects and instead focused on the pre-steady-state determination of solvent, primary, and multiple kinetic isotope effects.

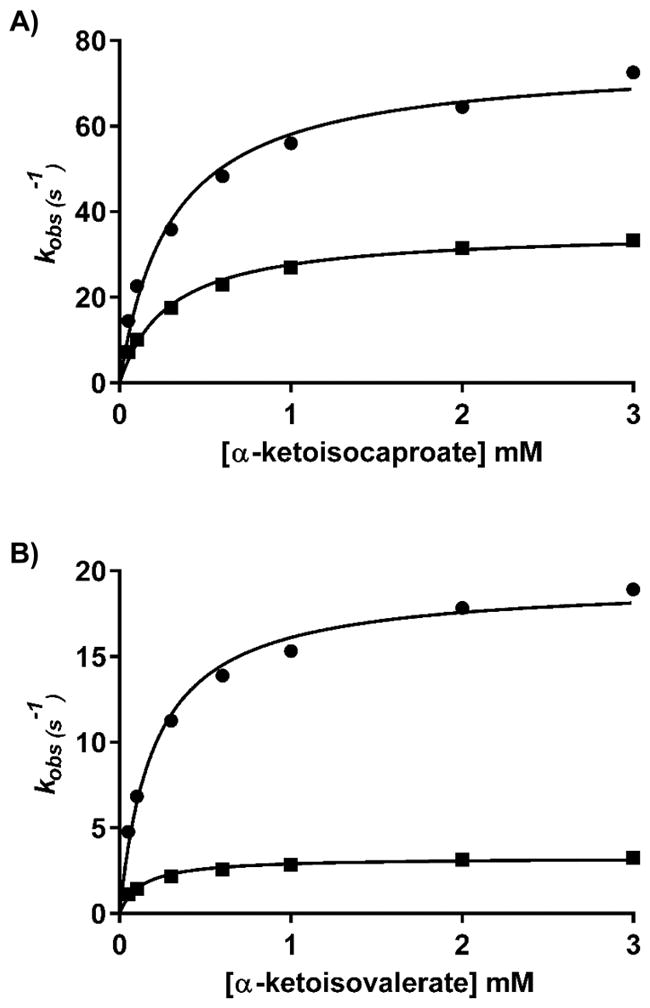

Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Isotope Effects on the Pong Reaction

Pre-steady-state experiments were conducted by averaging at least six traces at each concentration of substrate under the conditions noted. The PMP form was generated by reacting the enzyme with L-glutamate until no absorbance due to the PLP form was present and then dialyzed in either H2O or D2O to remove the released α-ketoglutarate. The MtIlvE–PMP solution (52 μM) was rapidly mixed with various concentrations of either α-ketoisocaproate (Figure 3A) or α-ketoisovalerate (Figure 3B). For α-ketoisocaproate, we determined a D2Okobs of 2.1 ± 0.2 that can be compared to the D2OV/K value found in steady-state experiments of 1.8 ± 0.3. For α-ketoisovalerate, we determined a D2Okobs of 5.9 ± 0.7 that can be compared to the D2OV/K value found in steady-state experiments of 6.7 ± 1.8. In both cases, the magnitudes of the solvent kinetic isotope effects were very comparable between the steady-state and pre-steady-state experiments. The reason why α-ketoisovalerate exhibits a solvent kinetic isotope effect so much larger than that of either α-keto-isocaproate or α-ketomethyl-pentanoic acid is unclear, but it is the smallest of the α-keto acid precursors and perhaps binds with a less rigid orientation in the active site, making any proton transfer more difficult and rate-limiting.

Figure 3.

Solvent KIEs of the pong half-reaction under single-turnover conditions. Each point represents the average of at least six traces recorded with 26 μM MtIlvE (monomer concentration) and increasing concentrations of substrates in H2O or D2O. (A) Observed rate constants (kobs) for the MtIlvE–PMP complex and increasing concentrations of α-ketoisocaproate (0.05, 0.1, 0.3, 0.6, 1, 2, and 3 mM) in H2O (●) or D2O (■). (B) kobs for the MtIlvE–PMP complex and increasing concentrations of α-ketoisovalerate (0.05, 0.1, 0.3, 0.6, 1, 2, and 3 mM) in H2O (●) or D2O (■).

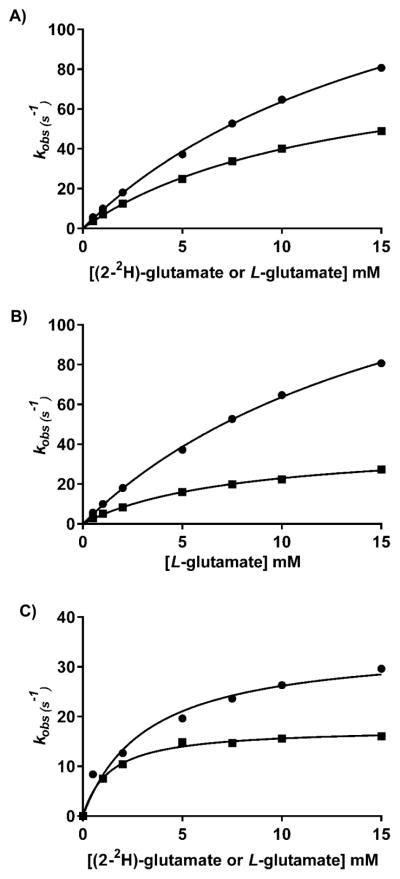

Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Isotope Effects on the Ping Reaction

For the first half-reaction involving L-glutamate, we also measured pre-steady-state kinetic isotope effects, both primary and solvent. In the case of the primary effect, there is no question about which step is the isotopically sensitive step, the cleavage of the α-C–H bond of the imine formed between L-glutamate and PLP. The Dkobs value we determined was 2.0 ± 0.1 (Figure 4A). This can be compared to the steady-state DV/KL-glutamate value of ~2 [1.8–2.1 (Table 2)]. The coincidence of the steady-state and pre-steady-state primary kinetic isotope effects suggests that L-glutamate has a near-zero commitment factor and that 2 represents the intrinsic primary deuterium kinetic isotope effect on the bond-cleaving reaction. We have also measured the solvent kinetic isotope effect for the first half-reaction. As shown in Figure 4B, there is a large solvent kinetic isotope effect of 4.4 ± 0.3, which is substantially larger than the value obtained in the steady state of 1.9. For such a complex series of steps that will be influenced by solvent isotopic composition, this may be due to the reduction of reverse internal commitments in the pre-steady-state experiments compared to those determined in the steady state. The two steps that seem most likely to be affected by D2O are the protonation of C4′ of PLP to generate PMP or the deprotonation of the water needed to hydrolyze the ketamine to generate α-ketoglutarate and PMP. A possible solution to this question involves the use of multiple kinetic isotope effects. Because we never observed any evidence of a quininoid intermediate, then the cleavage of the α-C–H bond would have to occur with the rapid formation of the C4′–H bond. We therefore determined the primary deuterium kinetic isotope effect in D2O. As seen in Figure 4C, the value of the effect was 2.0 ± 0.2, a value indistinguishable from the primary effect in H2O (Figure 4A, 2.0 ± 0.1). Ketimine hydrolysis cannot be the source of the large pre-steady-state solvent isotope effect because the absorbance changes occur prior to ketimine hydrolysis. Because transimination is also unlikely to produce changes in the absorbance of the PLP cofactor, C4′ protonation would appear to be the likely step that is sensitive to solvent isotopic composition. The prediction can be made that if α-C– H bond cleavage and C4′ protonation were stepwise, the relative rate limitation of α-C–H bond cleavage would decrease as would the magnitude of the primary isotope effect. Only if both the primary and solvent effects are reflecting the same chemical step will the magnitude of the primary kinetic isotope effect be unaffected by solvent isotopic composition. This argues for the synchronous α-C–H bond cleavage reaction and protonation at C4′, a concerted 1,3-prototropic shift mechanism, in which the α-C–H bond is being broken and the C4′–H bond is being made in the same transition state, a pseudoazaallylic rearrangement in which both isotopically sensitive steps are occurring nearly synchronously. This concerted 1,3-prototropic shift mechanism has been reported for aspartate aminotransferase32 and dialkylglycine decarboxylase, where decarboxylation and C4′ protonation occur synchronously.33

Figure 4.

Solvent, primary, and multiple KIEs of the ping half-reaction under single-turnover conditions. Each point represents the average of at least six traces collected with 26 μM MtIlvE (monomer concentration) and increasing concentrations of substrates in H2O or D2O. (A) kobs for the MtIlvE–PLP complex and increasing concentrations of glutamate in H2O (●) or D2O (■). (B) kobs for the MtIlvE–PLP complex and increasing concentrations of glutamate (●) or [2-2H]glutamate (■) (0.5, 1, 2, 5, 7.5, 10, and 15 mM) in H2O. (C) kobs for the MtIlvE–PLP complex and increasing concentrations of glutamate (●) or [2-2H]glutamate (0.5, 1, 2, 5, 7.5, 10, and 15 mM) in D2O (■).

CONCLUSION

Branched-chain aminotransferases have become a target of interest in the past several years. hBCATm has been implicated in obesity in humans, and significant efforts have been made to develop lead compounds capable of inhibiting its activity.35 The branched-chain aminotransferase MtIlvE catalyzes an essential reaction for the growth and survival of M. tuberculosis and is therefore a candidate for the development of inhibitors.

Numerous studies of PLP-dependent enzymes have reported the existence of multiple partially rate-determining steps.16,31,32,34 The chemical mechanisms of amino acid transaminases have been known for decades and are similar. In the case of MtIlvE, we could find no evidence of the existence of a quininoid intermediate under any conditions at the shortest reaction times (~3 ms). We observed large steady-state primary deuterium kinetic isotope effects using [2-2H]-glutamate, arguing that proton abstraction is partially rate-limiting. We also observed large steady-state solvent kinetic isotope effects in both the ping and pong reactions. These were additionally reproduced in single-turnover pre-steady-state experiments. The most mechanistically important conclusion, based on the pre-steady-state multiple kinetic isotope effect, suggests that the removal of a proton from C2 of the external aldimine and protonation at C4′ of the cofactor occur synchronously. This azaallylic rearrangement is presumably the reason why we failed to observe the quininoid intermediate (Scheme 3).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI060899 to J.S.B. and a Science Without Boarders fellowship (CAPES, Coordenaçãde Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil) to T.M.A.F.

We thank Dr. Javier Suarez (Johnson & Johnson) for discussions about data fitting of single-turnover KIEs. We also acknowledge Dr. Ariel Willis for assistance with the use of the stopped flow and Dr. Scott Cameron for insightful discussions. We also acknowledge Dr. Michael D. Toney for critical reading of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- TB

tuberculosis

- MDR

multidrug resistant

- XDR

extensively drug resistant

- TDR

totally drug resistant

- BCAAs

branched-chain amino acids

- BCATs

branched-chain aminotransferases

- PLP

pyridoxal 5′-phosphate

- PMP

pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate

- D-CS

D-cycloserine

- MtIlvE

branched-chain aminotransferase IlvE

- GDH

glutamate dehydrogenase

- NADH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- KIE

kinetic isotope effect

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00928.

Four figures (S1–S4) that show measurements to determine the extinction coefficient of PLP and PMP bound to MtIlvE, time course of spectral changes to PLP and PMP, 1H NMR spectrum of [2-2H]-L-glutamate, and pH dependence of the primary kinetic isotope effect (PDF)

References

- 1.Velayati AA, Masjedi MR, Farnia P, Tabarsi P, Ghanavi J, Ziazarifi AH, Hoffner SE. Emergence of new forms of totally drug-resistant tuberculosis bacilli: super extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis or totally drug-resistant strains in iran. Chest. 2009;136:420–425. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franco TM, Rostirolla DC, Ducati RG, Lorenzini DM, Basso LA, Santos DS. Biochemical characterization of recombinant guaA-encoded guanosine monophosphate synthetase (EC 6.3.5.2) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv strain. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;517:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Tuberculosis Report. 20. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hondalus MK, Bardarov S, Russell R, Chan J, Jacobs WR, Jr, Bloom BR. Attenuation of and protection induced by a leucine auxotroph of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2888–2898. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2888-2898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen K, Ranganathan UD, Van Rompay KK, Canfield DR, Khan I, Ravindran R, Luciw PA, Jacobs WR, Jr, Fennelly G, Larsen MH, Abel K. A recombinant attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine strain is safe in immunosuppressed simian immunodeficiency virus-infected infant macaques. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19:1170–1181. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00184-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grandoni JA, Marta PT, Schloss JV. Inhibitors of branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis as potential antituberculosis agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:475–482. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tremblay LW, Blanchard JS. The 1.9 A structure of the branched-chain amino-acid transaminase (IlvE) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Acta Crystallogr, Sect F: Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2009;65:1071–1077. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109036690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venos ES, Knodel MH, Radford CL, Berger BJ. Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase and methionine formation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Microbiol. 2004;4:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-4-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutson S. Structure and function of branched chain aminotransferases. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;70:175–206. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(01)70017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castell A, Mille C, Unge T. Structural analysis of mycobacterial branched-chain aminotransferase: implications for inhibitor design. Acta Crystallogr, Sect D: Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:549–557. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910004877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eliot AC, Kirsch JF. Pyridoxal phosphate enzymes: mechanistic, structural, and evolutionary considerations. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:383–415. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grishin NV, Osterman AL, Brooks HB, Phillips MA, Goldsmith EJ. X-ray structure of ornithine decarboxylase from Trypanosoma brucei: the native structure and the structure in complex with alpha-difluoromethylornithine. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15174–15184. doi: 10.1021/bi9915115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prosser GA, de Carvalho LP. Reinterpreting the mechanism of inhibition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis D-alanine:D-alanine ligase by D-cycloserine. Biochemistry. 2013;52:7145–7149. doi: 10.1021/bi400839f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fenn TD, Holyoak T, Stamper GF, Ringe D. Effect of a Y265F mutant on the transamination-based cycloserine inactivation of alanine racemase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5317–5327. doi: 10.1021/bi047842l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spies MA, Toney MD. Multiple hydrogen kinetic isotope effects for enzymes catalyzing exchange with solvent: application to alanine racemase. Biochemistry. 2003;42:5099–5107. doi: 10.1021/bi0274064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong W, Chen L, Xie J. Molecular basis underlying Mycobacterium tuberculosis D-cycloserine resistance. Is there a role for ubiquinone and menaquinone metabolic pathways? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18:691–701. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.902937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amadasi A, Bertoldi M, Contestabile R, Bettati S, Cellini B, Luigi di Salvo M, Borri-Voltattorni C, Bossa F, Mozzarelli A. Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate enzymes as targets for therapeutic agents. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1291–1324. doi: 10.2174/092986707780597899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah SA, Shen BW, Brunger AT. Human ornithine aminotransferase complexed with L-canaline and gabaculine: structural basis for substrate recognition. Structure. 1997;5:1067–1075. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goto M, Miyahara I, Hirotsu K, Conway M, Yennawar N, Islam MM, Hutson SM. Structural determinants for branched-chain aminotransferase isozyme-specific inhibition by the anticonvulsant drug gabapentin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37246–37256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506486200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allaudeen HS, Ramakrishnan T. Biosynthesis of isoleucine and valine in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37 Rv. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125:199–209. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90655-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith EL, Pisziewicz D. Bovine glutamate dehydrogenase. The pH dependence of native and nitrated enzyme in the presence of allosteric modifiers. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:3089–3092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Czekster CM, Vandemeulebroucke A, Blanchard JS. Kinetic and chemical mechanism of the dihydrofolate reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry. 2011;50:367–375. doi: 10.1021/bi1016843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karsten WE, Ohshiro T, Izumi Y, Cook PF. Reaction of serine-glyoxylate aminotransferase with the alternative substrate ketomalonate indicates rate-limiting protonation of a quinonoid intermediate. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15930–15936. doi: 10.1021/bi051407p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou X, Toney MD. pH studies on the mechanism of the pyridoxal phosphate-dependent dialkylglycine decarboxylase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:311–320. doi: 10.1021/bi981455s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnackerz KD, Feldmann K, Hull WE. Phosphorus-31 nuclear magnetic resonance study of D-serine dehydratase: pryridoxal phosphate binding site. Biochemistry. 1979;18:1536–1539. doi: 10.1021/bi00575a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hermes JD, Roeske CA, O’Leary MH, Cleland WW. Use of multiple isotope effects to determine enzyme mechanisms and intrinsic isotope effects. Malic enzyme and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5106–5114. doi: 10.1021/bi00263a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Northrop DB. Steady-state analysis of kinetic isotope effects in enzymic reactions. Biochemistry. 1975;14:2644–2651. doi: 10.1021/bi00683a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griswold WR, Castro JN, Fisher AJ, Toney MD. Ground-State Electronic Destabilization via Hyperconjugation in Aspartate Aminotransferase. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8436–8438. doi: 10.1021/ja302809e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldberg JM, Kirsch JF. The reaction catalyzed by Escherichia coli aspartate aminotransferase has multiple partially rate-determining steps, while that catalyzed by the Y225F mutant is dominated by ketimine hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5280–5291. doi: 10.1021/bi952138d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Julin DA, Kirsch JF. Kinetic isotope effect studies on aspartate aminotransferase: evidence for a concerted 1,3 prototropic shift mechanism for the cytoplasmic isozyme and L-aspartate and dichotomy in mechanism. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3825–3833. doi: 10.1021/bi00435a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou X, Jin X, Medhekar R, Chen X, Dieckmann T, Toney MD. Rapid kinetic and isotopic studies on dialkylglycine decarboxylase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1367–1377. doi: 10.1021/bi001237a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun S, Toney MD. Evidence for a two-base mechanism involving tyrosine-265 from arginine-219 mutants of alanine racemase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4058–4065. doi: 10.1021/bi982924t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borthwick JA, Ancellin N, Bertrand SM, Bingham RP, Carter PS, Chung CW, Churcher I, Dodic N, Fournier C, Francis PL, Hobbs A, Jamieson C, Pickett SD, Smith SE, Somers DO, Spitzfaden C, Suckling CJ, Young RJ. Structurally Diverse Mitochondrial Branched Chain Aminotransferase (BCATm) Leads with Varying Binding Modes Identified by Fragment Screening. J Med Chem. 2016;59:2452–2467. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.