ABSTRACT

Background. Official French health care policy recommends vaccinations against hepatitis B for all infants and at-risk adults. Attendees at our free testing center for sexually transmitted infections (FTC-STI) routinely express hepatitis B vaccine hesitancy. We aimed in this exposed population to explore the extent of knowledge concerning HBV infection, to quantify HBV vaccine refusal, and to identify the reasons for this refusal. Methods. During a 3-month period in 2013, all attendees at the Grenoble FTC-STI were given an anonymous questionnaire exploring their knowledge of hepatitis B, perception of the hepatitis B vaccine, acceptance of free same-day hepatitis B vaccination, and reasons for refusing this offer (where applicable). Results. The questionnaire was completed by 735 attendees (64.7% of those attending during the study period)(59.9% men; age 27.9 ± 9.2). Most respondents identified hepatitis B as a potentially severe, potentially lifelong illness existing in France. Concerning the hepatitis B vaccine, less than 50% totally or mostly agreed that it is safe; when asked whether the vaccine is dangerous, 44.2% answered “I don't know” and 14.0% agreed; when asked whether the vaccine is “not well characterized,” 45.0%, answered “I don't know” and 26.5% agreed. When asked whether they mistrust the hepatitis B vaccine or all vaccines in general, 39.0% and 28.9% of those unvaccinated agreed, respectively. Two thirds refused to get vaccinated on the same day. When asked whether they were afraid of the adverse effects of this vaccine, only 18.7% disagreed. Conclusion. Negative perceptions of the hepatitis B vaccine are widespread in this at-risk population. Consequently, a successful communication strategy must reassure this at-risk population of the vaccine's innocuous nature.

Keywords: hepatitis B, hesitancy, perceptions, side effects, sexually transmitted infection, vaccine

Introduction

In the last 20 years, French policies concerning vaccination against the hepatitis B virus (HBV) have gone through various phases.1 From 1995 to 1998, the vaccine was recommended for all infants under 2 y old and for all children entering middle school. However, the general recommendation to vaccinate the latter was withdrawn by French health authorities in 1998. This decision was motivated by potential uncertainties concerning vaccine safety, in particular the suspected risk of vaccine-induced multiple sclerosis and other demyelinating diseases.2 Although this risk was disproven by various studies3 in subsequent years, a sizable proportion of the French population likely interpreted these changes in vaccination policy as proof of the dangerous nature of the vaccine.4 Apart from encouraging the immunization of infants, French policies continue to recommend catch-up vaccinations for children up to the age of 16 and immunization of unvaccinated adults at risk, including healthcare workers and those with at-risk sexual behavior.

In France, the prevalence of positive HBs antigen is 0.65%.5 Due to the predominantly sexual transmission of HBV, detecting and preventing infection is part of the services offered by public free testing centers for sexually transmitted infections (FTC-STI). Testing for HBV infection is proposed to all FTC-STI attendees, and free hepatitis B vaccinations are offered to all attendees who test negative for the HBs antigen, anti-HBs antibodies, and anti-HBc antibodies and who have not yet received a complete vaccination schedule (3 injections). Refusal of hepatitis B vaccination is common, even though FTC-STI attendees, who often engage in unprotected sexual intercourse, may be at a higher risk than the general population. We have informally observed at Grenoble free testing center that this refusal is generally the result of a negative attitude toward the hepatitis B vaccine and of the perceived risk of adverse effects. It is crucial to precisely explore the reasons for this refusal; it is also important do determine whether attendees have a good knowledge of the disease, to better define the message we have to deliver to them when proposing a vaccine.

The present study relied on questionnaires to explore the perceptions of attendees at our free testing center concerning hepatitis B vaccine, thereby allowing us to quantify the proportion of those refusing the vaccine and to identify the reasons for this refusal. We also aimed to investigate whether the attendees knew enough about the infection to identify hepatitis B as a sexually transmitted, vaccine-preventable disease, and whether there was an association between knowledge about the disease and vaccine perception.

Results

Between 1 January and 31 December 2013, a total of 4,026 people attended our FTC-STI. Of the 1,136 attendees who used the services during the study period (1 March to 13 June) 735 (64.7%) people were included in the study (i.e., those able to or accepting to complete the questionnaire). The studied population had a mean age of 27.9 ± 9.2 y and was composed of 59.9% men. Those attending the center in 2013 outside of the study period had a similar sex ratio, but were slightly older (29.1 years, p < 0.01); the same was true for those attending the center during the study period but not included (30.8 years, p < 0.01).

Hepatitis B perception (Table 1)

Table 1.

Perception of the hepatitis B virus.

|

(number of people who answered the question) |

Totally/mostly agree |

Totally/mostly disagree |

I don't know |

| This disease is not severe (728) | 7.2% | 80.9% | 11.9% |

| This disease does not exist in France (728) | 2.4% | 85.8% | 11.8% |

| This disease can be lethal (728) | 63.3% | 8.1% | 28.6% |

| One always recovers from this disease (728) | 11.7% | 54.4% | 33.9% |

| This disease mostly affects alcoholics (727) | 9.0% | 45.9% | 45.1% |

| This disease can affect anybody (730) | 88.9% | 1.8% | 9.3% |

| This disease mostly affects young people (727) | 1.6% | 84.4% | 14.0% |

| This disease can last a lifetime (729) | 54.9% | 4.9% | 40.2% |

| This disease can cause cancer (728) | 27.3% | 10.1% | 62.6% |

| This disease affects the liver (731) | 51.4% | 4.0% | 44.6% |

A 10-item multiple-choice questionnaire was used to explore patient perceptions of hepatitis B. Most respondents identified this disease as a potentially lethal, and potentially lifelong disease existing in France that can potentially affect anybody. Nevertheless, 48.6% did not know that hepatitis B affects the liver, and only 27.2% of the respondents totally agreed (12.8%) or mostly agreed (14.4%) that HBV infection carries a risk of cancer. There was no difference in sex and age concerning the knowledge of hepatitis B (for the questions “this disease can affect anybody;" “this disease can be lethal”; “this disease can give cancer”).

Concerning possible ways of preventing hepatitis B, condom use was identified by 47.5%, vaccination by 36.2%, and disposable needles by 8.2% of respondents. Roughly a quarter of the respondents declared that they did not know how to prevent hepatitis B.

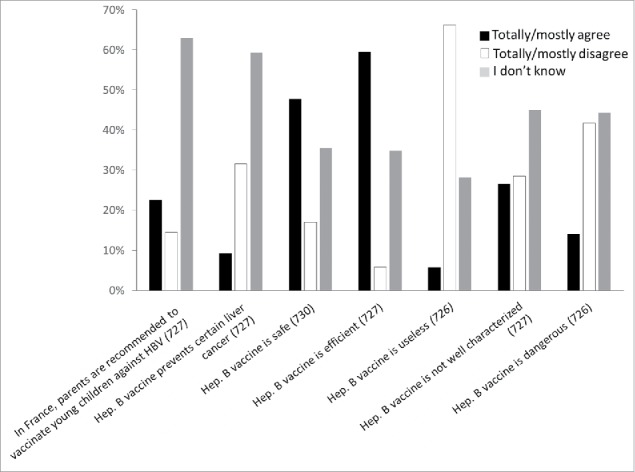

Hepatitis B vaccine perception (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Perception of hepatitis B vaccine.

A 7-item multiple-choice questionnaire was used to explore positive and negative perceptions of the HBV vaccine. The collected answers reflect a low level of trust concerning the safety of this vaccine and, to a lesser extent, concerning its efficiency. Indeed, when asked whether the vaccine is efficient, 59.4% totally or mostly agreed, only 5.8% mostly or totally disagreed, and 34.8% of respondents answered “I don't know.” When asked whether the vaccine can prevent liver cancer, most of the respondents (59.3%) answered “I don't know," and 32.4% mostly or strongly disagreed. On the other hand, when asked whether the vaccine is safe, less than 50% of the respondents totally or mostly agreed; when asked whether the vaccine is dangerous only 14.0% totally or mostly agreed and 44.2% answered “I don't know.” When asked whether the vaccine is “not well characterized,” only 26.5% totally or mostly agreed, and 45.0% answered “I don't know.” Negative perceptions of the vaccine safety and usefulness were correlated: 51.5% of those stating that the hepatitis B vaccine is dangerous vs 17.0% of those stating that it is not considered the vaccine useless (p < 0.01).

Respondents who totally or mostly agreed that the HBV vaccine is dangerous had the same mean age as those who mostly or /totally disagreed (28.0 vs. 28.4 years; p = 0.31); both groups also had similar sex ratios (54.3% men vs. 61.6% men; p = 0.39). Similarly, those who considered the vaccine useless showed similar age and sex data as those who considered it is not useless.

Only 22.5% knew (“totally or mostly agree”) that the vaccine is routinely proposed to young children.

Past immunizations

Of all respondents, 403 (54.8%) stated that they had never received the hepatitis B vaccine, of which 29.8% stated that they had not been previously vaccinated because of mistrust, 9.4% because their parents refused to have them vaccinated, 25.9% because they were never offered the vaccination, 16.4% because they did not know that the hepatitis B vaccine exists, and 9.5% because they did not feel the vaccination concerned them.

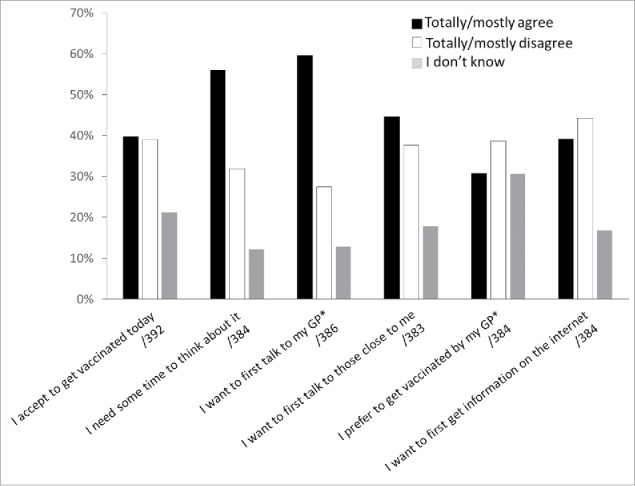

Attendee responses to the proposed vaccination

Free same-day hepatitis B vaccination was proposed to attendees lacking prior immunization (n = 403), and a 6-item questionnaire was used to explore attendee attitudes toward this proposition (Fig. 2). More than one third (39.8%) mostly or totally agreed to an immediate free vaccination. Between those who accepted and those who refused to receive the vaccine, there were no significant differences concerning the answers to “Hepatitis B is not severe” (p = 0.30), “The hepatitis B vaccine is dangerous” (p = 0.33), and “The hepatitis B vaccine is useless” (p = 0.76). Respondents also stated that they needed some time to think about it before making the decision (56.0%), that they wanted to talk about it with their general practitioner (59.6%) or with friends and family members (44.6%), or that they chose to obtain additional information on the internet (39.0%); 30.7% mentioned that they preferred being vaccinated by their general practitioner.

Figure 2.

Reactions toward hepatitis B vaccine offer (number of respondents). *GP: general practitioner.

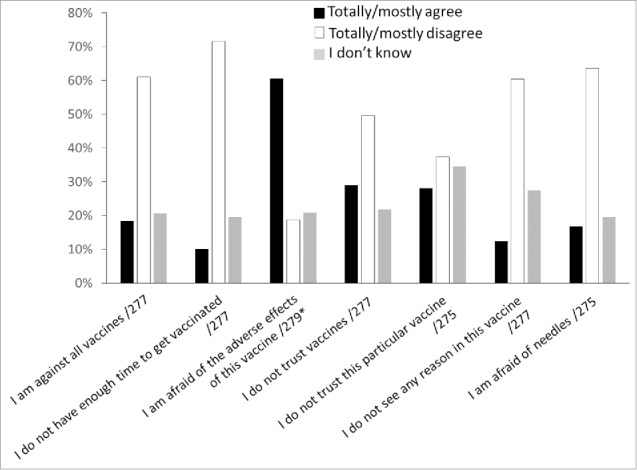

Attendees who refused to get vaccinated on the same day were asked to provide the reasons for this refusal (Fig. 3). When asked whether they are against all vaccines, 16.4% totally or mostly agreed; when asked whether they mistrust all vaccines and whether they mistrust this particular vaccine, 28.9% and 37.0% agreed (totally or mostly), respectively; when asked whether they are afraid of the adverse effects of this vaccine, only 18.7% disagreed (totally or mostly). Fear of needles was mentioned by merely 16.7% (totally or mostly agreed).

Figure 3.

Causes cited by subjects to justify hepatitis B vaccine refusal. *Including 2 respondents who answered that they would not refuse to get vaccinated.

Hepatitis B vaccine perception and vaccine status

Hepatitis B vaccine perception and vaccine status were correlated. Indeed, 63.5% of respondents who considered (totally or mostly agreed) the hepatitis B vaccine to be safe were already vaccinated, compared with 44.4% of those who did not (mostly or totally disagreed) (p < 0.01). Consistent with this finding, 43.5% of respondents who considered the hepatitis B vaccine dangerous (totally or mostly agree) were already vaccinated, compared with 65.5% of those who did not (mostly and totally disagree) (p < 0.01). Of those respondents who answered “I don't know” to “The HBV vaccine is dangerous” and to “The HBV vaccine is safe” 50.2% and 49.9% were vaccinated, respectively.

Discussion

Vaccines constitute a prodigious achievement for human health and quality of life.6 The benefit-risk balance is extremely favorable compared with most other medical procedures, including antibacterial and antiviral therapy. However, hesitancy in the general population poses a challenge to vaccination programs. In developed countries with high standards of care, which includes most European nations, vaccines are considered dangerous by a growing number of people, including parents of young children. In France, vaccine hesitancy mainly concerns the hepatitis B vaccine (although other vaccines are also affected) and may be the result of recent public health decisions. In 1994, a hepatitis B vaccination campaign was launched in France. The campaign targeted all children under the age of 2 and children in the first year of middle school (1994-1998 campaign). In the following 5 years, around 20 to 27 million people were vaccinated, including 7 to 9 million under the age of 151. In 1998, however, the French Health Ministry withdrew (somehow awkwardly) the vaccine recommendations for children in middle school because of growing rumors concerning an alleged link between the hepatitis B vaccine and the onset of MS. As might have been predicted, this decision likely contributed to legitimizing mistrust of the hepatitis B vaccine: some might have interpreted it as an official acknowledgment of the vaccine's causal involvement in MS. Since then, HBV vaccine coverage for 24-month old infants has reached a nadir of 26% in 2004; the national health insurance agreement to bear full medical costs for the hexavalent vaccine (tetanus, diphtheria, poliomyelitis, pertussis, Hæmophilus influenzae b, and hepatitis B) in 2008 is associated with a rise in vaccination coverage.7 The present study aimed to assess the state of current knowledge concerning hepatitis B and explore prevalent attitudes toward the hepatitis B vaccine in the population of teenagers and adults attending our FTC-STI. Because people come to our center to seek advice, diagnosis, and/or treatment concerning STIs, attendees are much more likely to be exposed to STIs than the general population. FTC-STI attendees therefore should be vaccinated against hepatitis B, as recommended by official French health policy. Consequently, it was important to determine whether attendees had positive or negative perceptions of this vaccine.

We observed that people attending our center were comparatively well informed about hepatitis B, although the proportion answering “I don't know” was often high (e.g., concerning the risk of cancer). This lack of knowledge suggests that health authorities and healthcare workers should better communicate the nature and associated risks of this disease, especially to an at-risk population such as FTC-STI attendees.

We also observed that a high proportion of respondents were either convinced of (agreed) or were unsure of (answered “I don't know”) the adverse effects associated with the hepatitis B vaccine. The fact that one third answered “I don't know” when asked whether the hepatitis B vaccine is safe might be equally striking as the fact that one third (among those refusing the vaccine) indicated that they mistrust the hepatitis B vaccine. Moreover, although only 14.0% agreed when asked whether the hepatitis B vaccine is dangerous, a remarkable 44.2% answered “I do not know.”

Our study therefore demonstrates the considerable, persistent mistrust to the hepatitis B vaccine in France; remarkably, there seems to be little doubt concerning the efficiency of the vaccine. These negative perceptions are consistent with the answers collected by a study on general attitudes toward vaccines in France8: In this study, 55% of the respondents stated that receiving a new vaccine makes them anxious, 22% said that premarketing studies fail to correctly identify dangerous vaccines, and 38% believed that a vaccine can trigger a severe form of the disease it is supposed to prevent.

Negative perceptions of the HBV vaccine have been documented previously. A study conducted in 2007 at the same type of free testing facility9 found that 12% of the respondents agreed, 18% disagreed, and 70% declared that they did not know when asked whether the hepatitis B vaccine could be responsible for neurological problems. In the 2005 French study “Health barometer” (conducted in the general population),10 90.5% of respondents declared that they were in favor or mostly in favor of vaccinations in general; negative perceptions of vaccinations were more prevalent in people over 65, in women, in unmarried people, in people who estimated that they were not well informed, and in people who had recently consulted a physician practicing homeopathy or acupuncture. The hepatitis B vaccine raised the highest proportion of disagreement (38.6%; 43.2% women and 32.4% men). (Note that in the year 2000, only 23.6% disagreed with hepatitis B vaccinations.) When the same study was conducted again in 2010,11 only 61.5% of 27,653 respondents declared that they were in favor or mostly in favor of vaccinations in general. The hepatitis B vaccine, which received 17%, was no longer the vaccine with the highest proportion of unfavorable answers; it had been replaced by the influenza A vaccine (77%), reflecting the conflicted attitudes toward generalized vaccination in France during the A(H1N1) pandemic in the winter of 2009-2010.

Several people who received the HBV vaccine between 1993 and 1998 declared that they experienced the onset of MS in the weeks or months following the injection, which led to the assertion that developing MS is connected to receiving the hepatitis B vaccination. Of the numerous subsequently conducted case-control, cohort and other studies, all12-22 excluding one23 were unable to establish a link between the hepatitis B vaccine and the onset or relapse of MS, prompting an official statement by French authorities in 2012 that receiving the HBV vaccine does not constitute a risk of developing a demyelinating disease.24 Our findings suggest that, although we did not precisely explore its influence, this controversy continues to affect attitudes toward HBV vaccination in the general population in France. In other countries, negative perceptions possibly focus on other vaccines. Indeed, the controversial link between the MMR vaccine and autism, triggered by a flawed study published in The Lancet in 1998,25 resulted in long-lasting resistance to this vaccine in the United Kingdom.26 This vaccine hesitancy suggests that communication campaigns by health authorities and healthcare workers should inform the population about the innocuous nature of the vaccine, the lack of data documenting a link with suspected adverse effects, and the high level of supervision and regulation of the vaccine use. Another case of national controversy can be found in Japan, where health authorities decided to suspend the HPV vaccine policy in 2013, resulting in growing negative perceptions. Interestingly, this decision not only affected vaccine perceptions in Japan, but also in Europe and in the USA.27

A very recent study conducted in 67 countries has shown that France has the highest proportion of vaccine hesitancy, with 41% of the respondents declaring that vaccines may be dangerous.28 Although these perceptions have likely been shaped by the various controversies mentioned previously, this proportion of the French population (41%) should not be characterized as exhibiting “conspiratorial thinking, denialism, low cognitive complexity in thinking patterns, reasoning flaws, and a habit of substituting emotional anecdotes for data”29; these are characteristics describing a highly critical anti-vaccine minority. However, in “the age-old struggle against the antivaccinationists”,30 each of these characteristics must be addressed to restore trust in vaccines in the increasingly hesitant majority.

Our study possessed several strengths. It is the largest study to date concerning hepatitis B vaccine perceptions in an at-risk, not professionally concerned adult population. Because the study was conducted anonymously, respondents were assumed more likely to answer truthfully to sensitive questions such as those concerning the risks associated with vaccines. Nevertheless, our study also suffered from several limitations. Given the study's particular setting, it included mostly people under 40 and (presumably) people without children (in France in 2010, the mean age for having a first child was 3031). The observed attitudes therefore might not reflect those of the general population, in particular those of parents of young children, which constitute an important group, taking into account that the hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for all infants. In addition, attendees filled out the questionnaires while waiting for their STI test results; therefore, most respondents were likely feeling anxious and stressed, which might have affected their answers. Furthermore, note that one third of eligible attendees did not complete the questionnaire (due to language issues, or merely because they preferred not to participate); their perceptions concerning the hepatitis B vaccine might differ from the perceptions of those who completed the questionnaire. Moreover, our study relied on self-filled questionnaires. Although this practice may assist in collecting honest responses, it also potentially introduces errors because questions might be misread or misunderstood. In addition, given that the respondents were attending an STI testing center, we considered this population to be globally “at risk.” However, at-risk behaviors (in particular sexual conduct) are not homogeneous, and respondents could have been classified into more precise risk categories. This added precision would have allowed us to determine whether the perceptions concerning vaccines differ for those in the highest risk category. Finally, we must also take into consideration that people attending our FTC-STI may not belong to the highest risk group in the population, but merely represent the fraction of those at risk who are concerned about their health (i.e., those with greater health concerns than others who are at risk but do not attend such centers). Vaccine perceptions may be different among people at risk who are, nevertheless, unconcerned about their health.

Conclusion

The hepatitis B vaccine continues to elicit negative perceptions of the vaccine's safety in a large proportion of the adult at-risk population in France. A successful communication strategy should address these perceptions as part of the immunization campaign, both for a mass communication strategy and in individual counseling environments. The high proportions of “I don't know” answers collected in the present study further suggest that general knowledge about hepatitis B should also be improved.

Population and methods

Free testing center for sexually transmitted infections (FTC-STI)

FTC-STI facilities were first created in 1988 across the entire French territory. These centers offer free testing for STIs and blood-transmitted infections, information and counseling on the prevention of these infections, and information about sexual health. Free hepatitis B vaccinations are offered to all unvaccinated and uninfected attendees. Additionally, the centers offer hepatitis A virus and meningococcal vaccinations to all male attendees who have sex with men (MSM). All services are offered anonymously to ensure privacy. Annually, roughly 4,000 people attend the Grenoble free testing center (overseen by the Conseil Général de l'Isère).

Questionnaires

From 1 March to 13 June 2013, all French-speaking and English-speaking attendees at the Grenoble center were asked to voluntarily complete a self-reported, anonymous questionnaire that collected diverse personal data (such as age and sex), their perceptions of HBV infection, of vaccines in general, and of the hepatitis B vaccine. All questions were multiple-choice (no open questions). The questionnaire was available in both French and English. Because we collected neither respondent names nor phone numbers, it was impossible to obtain additional answers after the respondents had left the FTC-STI.

Statistics

The Epi Info 7.1.3 software package (CDC, Atlanta, Georgia) was used for statistical analyses. Binomial qualitative variables between two groups were compared with the chi2 test. Quantitative variables between two groups were compared with the Wilcoxon test.

The study was conducted in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Ethics approval

We did not seek approval from an ethical authority because the study relied entirely on anonymous questionnaires, voluntary participation, and on the results of tests (hepatitis B status) that are routinely performed for all center attendees (and were not performed solely for the purpose of this study).

Abbreviations

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- FTC-STI

free testing center for sexually transmitted diseases

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

The study was funded by the Conseil Général de l'Isère, Grenoble, France.

Author contributions

LM, SH, and OE designed the questionnaire. LM and SH collected the data. LM, SH, and LG performed data analysis. OE wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- [1].Denis F, Levy-Bruhl D. Mass vaccination against hepatitis B: the French example. Curr Topics Microbiol Immunol 2006; 304:115-29; PMID:16989267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Herroelen L, de Keyser J, Ebinger G. Central-nervous-system demyelination after immunisation with recombinant hepatitis B vaccine. Lancet 1991; 338(8776):1174-5; PMID:1682594; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92034-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mailand MT, Frederiksen JL. Vaccines and multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. J Neurol 2016; [Epub ahead of print]; PMID:27604618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Balinska MA, Leon C. Perceptions of hepatitis B vaccination in France. Analysis of three surveys. Revue d'epidemiologie Et De Sante Publique 2006; 54 Spec No 1:1S95-1S101; PMID:17073136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Meffre C, Le Strat Y, Delarocque-Astagneau E, Dubois F, Antona D, Lemasson JM, Warszawski J, Steinmetz J, Coste D, Meyer JF, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections in France in 2004: social factors are important predictors after adjusting for known risk factors. J Medical Virol 2010; 82(4):546-55; PMID:20166185; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jmv.21734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Greenwood B. The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Philosophical Transactions Royal Soci London Series B, Biol Sci 2014; 369(1645):20130433; PMID:24821919; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1098/rstb.2013.0433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Levy-Bruhl D. Successes and failures of anti-HBV vaccination in France: historical background and questions for research. Revue d'epidemiologie Et De Sante Publique 2006; 54 Spec No 1:1S89-1S94; PMID:17073135 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Direction générale de la Santé, Comité technique des vaccinations. Guide des vaccinations. Édition 2012. Saint-Denis: Inpes, 2012. Available at: http://www.inpes.sante.fr/10000/themes/vaccination/guide-vaccination-2012/pdf/GuideVaccinations2012_Opinions_et_comportements_vis_vis_de_la_vaccination.pdf.

- [9].Tosini W, Rioux C, Pélissier G, Bouvet E. Étude de perception des risques de l'hépatite virale B et de sa prévention vaccinale dans une Consultation de dépistage anonyme et gratuit (CDAG) parisienne en 2007. BEH 2009; 2009(20-21):217-0 [Google Scholar]

- [10].http://www.inpes.sante.fr/Barometres/BS2005/pdf/BS2005_Vaccination.pdf. 2005

- [11].Peretti-Watel P, Verger P, Raude J, Constant A, Gautier A, Jestin C, Beck F. Dramatic change in public attitudes toward vaccination during the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic in France. Euro Surveill 2013; 18(44): 15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sturkenboom MC, Abenhaim L, Wolfson C, Roulet E, Heinzelf O, Gout O. Vaccinations, demyelination, and multiple sclerosis study (VDAMS). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 1999; 8:S170-1 [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Rossier M, Suissa S, Tardieu M. Hepatitis B vaccination and the risk of childhood-onset multiple sclerosis. Archilves Pediatrics Adolescent Med 2007; 161(12):1214-5; ; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Zipp F, Weil JG, Einhaupl KM. No increase in demyelinating diseases after hepatitis B vaccination. Nat Med 1999; 5(9):964-5; PMID:10470051; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/12376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sadovnick AD, Scheifele DW. School-based hepatitis B vaccination programme and adolescent multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2000; 355(9203):549-50; PMID:10683009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02991-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ascherio A, Zhang SM, Hernan MA, Olek MJ, Coplan PM, Brodovicz K. Hepatitis B vaccination and the risk of multiple sclerosis. N Eng J Med 2001; 344(5):327-32; PMID:11172163; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJM200102013440502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Touze E, Fourrier A, Rue-Fenouche C, Ronde-Oustau V, Jeantaud I, Begaud B, Alpérovitch A. Hepatitis B vaccination and first central nervous system demyelinating event: a case-control study. Neuroepidemiology 2002; 21(4):180-6; PMID:12065880; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000059520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fourrier A, Touze E, Alperovitch A, Begaud B. Association between hepatitis B vaccine and multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety 1999; 8:S140-1 [Google Scholar]

- [19].DeStefano F, Verstraeten T, Jackson LA, Okoro CA, Benson P, Black SB, Shinefield HR, Mullooly JP, Likosky W, Chen RT. Vaccinations and risk of central nervous system demyelinating diseases in adults. Archives Neurol 2003; 60(4):504-9; PMID:12707063; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/archneur.60.4.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Suissa S, Tardieu M. Hepatitis B vaccine and the risk of CNS inflammatory demyelination in childhood. Neurology 2009; 72(10):873-80; PMID:18843097; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1212/01.wnl.0000335762.42177.07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Assi S, Tardieu M, Suissa S, KsgotFN Society. Hepatitis B vaccine and risk of relapse after a first childhood episode of CNS inflammatory demyelination. Brain 2007; 130(Pt 4):1105-10; PMID:17276994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Confavreux C, Suissa S, Saddier P, Bourdes V, Vukusic S, Vaccines in Multiple Sclerosis Study G Vaccinations and the risk of relapse in multiple sclerosis. Vaccines in Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. N Eng J Med 2001; 344(5):319-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hernan MA, Jick SS, Olek MJ, Jick H. Recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and the risk of multiple sclerosis: a prospective study. Neurology 2004; 63(5):838-42; PMID:15365133; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1212/01.WNL.0000138433.61870.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Official Statement of the Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de santé. February 2012. Bilan de pharmacovigilance et profil de securite d'emploi des vaccins contre l'hepatite B Available at: http://ansmsantefr/content/download/38801/509771/version/1/file/Bilan-VHBpdf.

- [25].Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, Linnell J, Casson DM, Malik M, Berelowitz M, Dhillon AP, Thomson MA, Harvey P, et al. Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet 1998; 351(9103):637-41; PMID:9500320; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11096-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Brown KF, Long SJ, Ramsay M, Hudson MJ, Green J, Vincent CA, Kroll JS, Fraser G, Sevdalis N. U.K. parents' decision-making about measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine 10 years after the MMR-autism controversy: a qualitative analysis. Vaccine 2012; 30(10):1855-64; PMID:22230590; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Larson HJ, Wilson R, Hanley S, Parys A, Paterson P. Tracking the global spread of vaccine sentiments: the global response to Japan's suspension of its HPV vaccine recommendation. Hum Vaccines Immunotherapeutics. 2014; 10(9):2543-50; PMID:25483472; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/21645515.2014.969618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, Cook AR, Jones NS. The State of Vaccine Confidence 2016: Global Insights Through a 67-Country Survey. Ebiomedecine 2016; 12:295-301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jacobson RM, Targonski PV, Poland GA. A taxonomy of reasoning flaws in the anti-vaccine movement. Vaccine 2007; 25(16):3146-52; PMID:17292515; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Poland GA, Jacobson RM. The age-old struggle against the antivaccinationists. N Eng J Med 2011; 364(2):97-9; PMID:21226573; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMp1010594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].INSEE (Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques ). http://www.insee.fr/fr/themes/document.asp?reg_id = 0&ref_id = T16F035. 2015