Abstract

Bone marrow obtained by iliac crest aspiration is a common source for harvesting mesenchymal stem cells, other progenitor cells, and associated cytokine/growth factors. Recent studies have reported good to excellent outcomes with the use of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) for pain relief in the treatment of focal chondral lesions and osteoarthritis of the knee. However, the harvesting and processing technique are crucial to achieve satisfactory results. Several studies have examined outcomes after BMAC injection, with encouraging results, but there is a lack of consensus in terms of the frequency of injection, the amount of BMAC that is injected, and the timing of BMAC injections. The purpose of this Technical Note was to describe a standardized bone marrow aspiration harvesting technique and processing method.

Bone marrow obtained by iliac crest aspiration is a common source for harvesting mesenchymal stem cells, other progenitor cells, and associated cytokine/growth factors. Because the use of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) is currently approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, it represents one of the few means for acquiring progenitor cells and growth factors for subsequent injection.1, 2, 3, 4

After density gradient centrifugation to remove red blood cells, granulocytes, immature myeloid precursors, and platelets, progenitor cells account for a small population within the bone marrow (0.001% to 0.01%).5, 6, 7 However, a high concentration of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor-β, and bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 7, which are reported to have anabolic and anti-inflammatory effects,8, 9, 10 are present in BMAC. Of note, it has been reported that BMAC has a considerable concentration of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA).11 This molecule inhibits IL-1 catabolism and therefore may be responsible for the beneficial symptomatic pain relief with this biologic approach.12

A recent systematic review reported good to excellent outcomes with the use of BMAC for the treatment of focal chondral defects and mild to moderate osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee with a relatively safe profile.13 However, harvesting and processing techniques are vital to achieve optimal molecular concentrations and of both stem cells and growth factors in order to ultimately achieve satisfactory results. The purpose of this Technical Note was to describe the bone marrow aspiration technique and processing method.

Patient Positioning

The patient can be positioned either supine or prone. In the supine position, BMAC is harvested from the anterior superior iliac spine or the iliac crest. In the prone position, BMAC is harvested from the posterior superior iliac crest region. When the patient is positioned prone, it is important that care is taken to ensure that all bony pressure points and areas of potential nerve compression are adequately padded. Monitored anesthesia (conscious sedation), local anesthesia, or general anesthesia can be used for this BMAC harvest procedure, we prefer positioning the patient in the prone position with light sedation monitored by an anesthesiologist for access to the posterior superior iliac crest. After palpation of the bony landmarks, the procedural site is sterilely prepared and widely draped to ensure an adequate field. The BMAC aspiration kit is opened and then the battery-powered BMAC aspiration device is sterilely draped (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Demonstrates patient positioning prior to bone marrow aspirate harvesting on a left iliac crest. Care should be taken to ensure that the harvest site is prepped in a completely sterile fashion. BMAC is harvested from the posterior superior iliac crest region. When the patient is positioned prone, it is important that care is taken to ensure that all bony pressure points and areas of potential nerve compression are adequately padded. Monitored anesthesia (conscious sedation), local anesthesia, or general anesthesia can be used for this BMAC harvest procedure, we prefer positioning the patient in the prone position with light sedation monitored by an anesthesiologist for access to the posterior superior iliac crest. (BMAC, bone marrow aspirate concentrate.)

Bone Marrow Aspiration

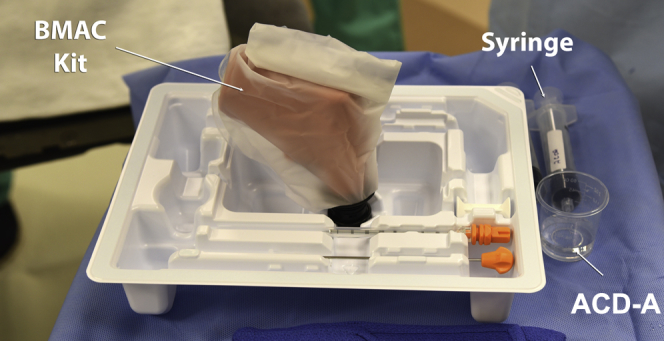

A bone marrow aspiration kit (MarrowStim; Biomet Biologics, Warsaw, IN) is used for bone marrow aspiration (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Photograph illustrating the bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) kit: bone marrow aspiration needle, trochar, a 30-mL syringe and the ACD-A solution. (ACD-A, anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, formula A.)

First the bony landmarks of the posterior iliac crest and sacroiliac joint are palpated (Fig 3). The skin is then injected down to and including the periosteum with 1% lidocaine without epinephrine. Then, the bone marrow aspiration trochar and needle are percutaneously inserted through the skin and subcutaneous tissues until it reaches the posterior iliac crest. Then, manual pressure is used to position the bone marrow aspiration trochar against the dense cortical bone, attempting to center it over the middle of the posterior crest cortical walls. The trajectory of the needle should be parallel to the iliac crest, or perpendicular to the ASIS or PSIS, depending on the harvest site used (Fig 3). A battery-powered power instrument is then used to drill the trochar and needle into the medullary cavity of the posterior iliac crest (Fig 4).

Fig 3.

Patient placed in the prone position: (A) palpation of the left posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS), (B) infiltration of local anesthetic in the trajectory of the harvesting, and (C) percutaneous insertion of the bone marrow aspiration (BMA) trochar parallel to the iliac crest.

Fig 4.

A sterilely draped power instrument being used to advance the trochar through the dense cortical bone (left PSIS) into the medullary cavity of the posterior iliac crest. Needle trajectory should be perpendicular to the PSIS. (PSIS, posterior superior iliac spine.)

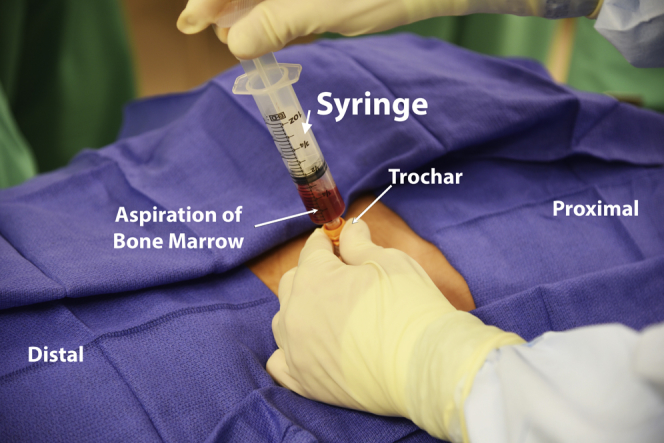

After the trochar is inserted into the posterior iliac crest but prior to aspiration, 1 mL of heparin (1,000 U/mL) should be preloaded into the syringe. Preloading the needles avoids clot formation and coagulation, which can diminish the ultimate yield from the aspiration. Approximately 60 mL of bone marrow is aspirated, which requires the use of two 30-mL syringes (Fig 5). At the conclusion of BMAC harvesting, a sterile dressing is applied to the harvest site (Fig 6).

Fig 5.

Aspiration of bone marrow on a left posterior superior iliac spine; the bone marrow aspiration needle is inserted into the cancellous bone of the iliac crest after penetrating the cortical bone using a power drill and the sample is obtained.

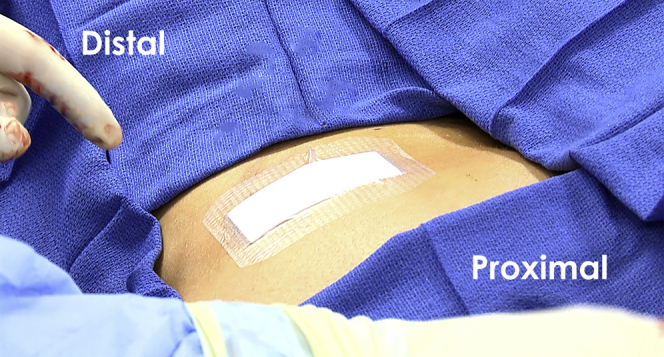

Fig 6.

Demonstrates placement of a sterile dressing to the harvest site (left posterior superior iliac spine) at the conclusion of the procedure. Care should be taken to ensure that the dressing is securely applied so that it does not get removed during patient repositioning.

Processing of the Bone Marrow Aspirate

The bone marrow aspirate (BMA) sample must be processed after it is harvested. BMA is filtered through a 200-μm-mesh filter into 50-mL conical tubes. Then, 1 to 1.5 mL of the filtered BMA is pipetted into a 2-mL microcentrifuge tube for hemanalysis and the sample complete blood count with differential is automatically recorded. Subsequently, 60 to 90 mL of BMA is transferred into 2 × 50-mL conical tubes, and initially centrifuged at 2,400 rpm for 10 minutes. After completion of this process, the buffy coat layer and platelet-poor plasma layer are extracted from the conical tube and discarded. The red blood cell layers are combined into 1 × 50-mL conical tube for second centrifugation (3,400 rpm for 6 minutes). Finally, the BMAC/white cell pellet is resuspended in platelet poor plasma, hemanalysis is performed and complete blood count with differential is recorded (including monocyte count) to assess the final product to inject.

Application of BMAC

BMAC can be sterilely injected into a variety of locations, including focal cartilage defects, arthritic joints, and the femoral head after core decompression.13, 14 The use of fluoroscopy, ultrasonography, or arthroscopy can help guide localization of the BMAC injection to the desired location of the joint.

The advantages and disadvantages of the described BMAC technique are reported in Table 1. A summary of the process of BMAC harvesting, processing, and application is displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Bone Marrow Aspiration Harvest and Application

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Technically easy to harvest | Potential pain during harvest with local anesthetic alone |

| No culture expansion | Variable stem cell quantity and quality depending on age |

| No risk of allogeneic disease transmission | Potentially detrimental effect of erythrocytes when used in intra-articular environment |

| Low risk of infection | |

| May be performed with concomitant procedure |

Table 2.

Step-by-Step Process for Harvest and Processing of Bone Marrow Aspiration

| Step | Details |

|---|---|

| Patient positioning | Selection of anesthetic plan for aspiration |

| Prone for PSIS harvest, supine for ASIS harvest | |

| Palpate site for aspiration | |

| Sterile preparation with antiseptic solution and sterile sheets/towels | |

| Bone marrow aspiration | Confirmation of bony landmarks |

| Injection of local anesthetic | |

| Preload aspiration syringe with 1 mL heparin (1,000 U/mL) | |

| Insert aspiration trocar and needle through skin, down to bone | |

| Penetrate cortex with power tool | |

| Collection of 60 mL of bone marrow aspirate | |

| Preparation of aspirate | Centrifuge according to protocol, obtain approximately 6 mL BMAC sample |

| Application of aspirate | Select indication for injection (e.g., rotator cuff repair, revision ACL, osteoarthritis) |

| Sterile preparation of selected injection site | |

| Injection of local anesthetic if selected for application | |

| Injection of aspirate in selected site |

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; ASIS, anterior superior iliac spine; BMAC, bone marrow aspirate concentrate; PSIS, posterior superior iliac spine.

Video 1 outlines the entire described technique, beginning with patient positioning, and concludes with intra-articular injection of BMAC.

Discussion

A stepwise technique for BMAC harvest and injection is reported in this Technical Note. Several recent clinical studies have reported on the extraction, processing, and clinical applications of BMAC in orthopaedic settings. Most recent studies have reported aspirating 60 mL of BMAC for their clinical applications.15, 16, 17, 18 However, other studies have reported using volumes as low as 30 mL19, 20 and as high as 120 mL.21 In the present Technical Note, 60 mL of BMAC was aspirated and later processed. In regard to BMAC processing, studies have used centrifugation, followed by BMAC activation with batroxobin enzyme.16, 17, 18, 21 The technique presented herein uses centrifugation but does not involve BMAC activation. Recent studies have also examined the quality of tissue repair after BMAC application.

Despite promising initial clinical studies, the optimal use for BMAC in certain orthopaedic conditions has not been identified. Moreover, studies have been limited in identifying the component of BMAC responsible for its desired clinical effects. Cassano and Fortier reported that BMAC has a significant amount of monocytes and IL-1RA.11, 22 It was hypothesized that IL-1RA may be responsible for the beneficial effects of the BMAC. Others have postulated that the beneficial effects of BMAC are related to the mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) content.7 The number of MSCs in BMAC, although relatively small in quantity, varies depending on the site of harvest and patient sex and age.13 Lavasani et al. postulated that the therapeutic effects of MSCs were mediated by secreted factors. However, the mechanism by which MSCs exert their effect is still unclear.23

Use of BMAC in patients with focal chondral defects and/or OA in the knee has been scarcely delineated. Three recent studies showed BMAC to be moderately effective in the treatment of OA.21, 24, 25 These studies used different outcome scores and treatment protocols, making inter-study analysis difficult. One of these studies, by Hauser and Orlofsky, reported improved symptoms and quality of life scores after injection of 2 to 6 injections of BMAC at 2- to 3-month intervals.25 This study highlights a potential treatment regimen of 2 to 6 injections over a 3-month period for the treatment of patients with OA.25 Furthermore, BMAC application has been shown to be more effective for patients with lesions that are of less than Kellgren-Lawrence grade 2 than for patients with advanced OA (Kellgren-Lawrence grade 4),21, 24 which may indicate a temporal relationship between BMAC administration and effect size. Taken together, these studies indicate that there is interplay between the frequency, amount, and timing of BMAC injections to observe positive effects in patients with OA.

The majority of studies reporting on BMAC application in patients with focal cartilage defects have reported good outcomes.21, 24, 25 Some studies have used microfracture or scaffolds in addition to BMAC application,26, 27 whereas other studies used scaffolds without microfracture.18 There is currently a lack of a consensus regarding the use of a scaffold or augmentation with BMAC injections. However, given the positive results of the aforementioned studies, further investigation is warranted. In patients with focal chondral defects, Gobbi et al. reported superior outcomes for patients younger than 45 years of age, with smaller chondral lesion size and with fewer lesions.10 This study adds to the existing literature in that there may be a subset of focal chondral defect patients who obtain the greatest benefit from BMAC injections.

Identifying the ideal number of BMAC treatments, the volume of treatment, and the timing of injections for BMAC has not been well characterized. Patients with focal chondral defects who received a single BMAC injection have been reported to have improved outcomes.9, 10, 11 In patients with OA, improved outcomes after BMAC injections have been reported; however, these studies used a variable number of treatments and had limited follow-up intervals.21, 24, 25 There is also a paucity of literature addressing the optimal augmentation method for BMAC application. Platelet-rich plasma has emerged as a promising augmentation method given its positive healing effects in degenerative knee pathologies.28 However, more studies are needed to elucidate the effects of platelet-rich plasma augmentation on BMAC effectiveness.

The safety of the MSC injected with BMAC is of the upmost importance and remains an issue that requires further study. The primary theoretical concern is that these cells may further divide into unwanted oncologic cell lineages.29 Self-limited pain and swelling were the most commonly reported adverse events at the injection site. Further studies are needed to allow for development of a comprehensive BMAC safety profile.

In conclusion, a stepwise approach to BMAC harvest, concentration, and subsequent injection is presented. Further study is necessary to clarify the number, volume, and timing of injections for BMAC treatment for specific knee pathologies. Moreover, standardization of the techniques of obtaining and processing BMAC aspirate is needed. The clinical role for BMAC is noted and we encourage the further study of BMAC injections in patients with advanced osteochondral defects and/or OA.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: R.F.L. receives support from Arthrex, Smith & Nephew, Ossur (consultancy fees), Health East, Norway and NIH R-13 grant for biologics (grants/grants pending); Arthrex, Smith & Nephew, and Ossur (royalties); and Arthrex, Smith & Nephew, and Ossur (patents).

Supplementary Data

The patient is positioned in the prone position. The left posterior iliac crest is identified and sterilely prepped and draped. Six milliliters of 1% lidocaine local anesthetic is injected into the skin and down to the periosteum over the desired BMAC harvest site. The bony landmarks are palpated again and a bone marrow aspiration trochar and needle assembly are percutaneously inserted through the skin and subcutaneous tissue until it reaches the posterior iliac crest. The trochar is then used to probe along the crest from anterior to posterior and then centered between the outer and inner walls of the iliac crest. Then a power instrument is used to advance the trochar through the dense cortical bone into the medullary cavity of the posterior iliac crest. Needle trajectory should be perpendicular to the PSIS. Prior to aspiration, 1 mL of ACD-A is preloaded into the syringe and injected into the trochar. Approximately 50-60 mL of bone marrow is aspirated, which requires the use of 30- or 10-mL syringes. Use of the 30-mL syringes offers more control during harvest and is the senior author's preferred method. The BMAC aspiration sample is then processed after it is harvested. The bone marrow is placed in a centrifuge. The sample is then spun at a rate of 3,200 rpm for 15 minutes. Typically, a 6-mL sample of BMAC is yielded after processing. The BMAC is subsequently injected either intra-articularly or into an extra-articular surgical site after the procedure is ended to ensure the BMAC is placed at its desired location. (ACD-A, anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, formula A; BMAC, bone marrow aspirate concentrate.)

References

- 1.Afizah H., Yang Z., Hui J.H., Ouyang H.W., Lee E.H. A comparison between the chondrogenic potential of human bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) and adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) taken from the same donors. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:659–666. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedenstein A.J., Piatetzky S., II, Petrakova K.V. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;16:381–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrakova K.V., Tolmacheva A.A., AIa F. Bone formation occurring in bone marrow transplantation in diffusion chambers. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1963;56:87–91. [in Russian] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaPrade R.F., Geeslin A.G., Murray I.R. Biologic Treatments for Sports Injuries II Think Tank-Current Concepts, Future Research, and Barriers to Advancement, Part 1: Biologics overview, ligament injury, tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:3270–3283. doi: 10.1177/0363546516634674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pittenger M.F., Mackay A.M., Beck S.C. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin D.R., Cox N.R., Hathcock T.L., Niemeyer G.P., Baker H.J. Isolation and characterization of multipotential mesenchymal stem cells from feline bone marrow. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:879–886. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00864-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chahla J., Piuzzi N.S., Mitchell J.J. Intra-articular cellular therapy for osteoarthritis and focal cartilage defects of the knee: A systematic review of the literature and study quality analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1511–1521. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.15.01495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnabel L.V., Mohammed H.O., Miller B.J. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) enhances anabolic gene expression patterns in flexor digitorum superficialis tendons. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:230–240. doi: 10.1002/jor.20278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarrel T., Fortier L. Temporal growth factor release from platelet-rich plasma, trehalose lyophilized platelets, and bone marrow aspirate and their effect on tendon and ligament gene expression. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1033–1042. doi: 10.1002/jor.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Indrawattana N., Chen G., Tadokoro M. Growth factor combination for chondrogenic induction from human mesenchymal stem cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:914–919. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cassano JM, Kennedy JG, Ross KA, Fraser EJ, Goodale MB, Fortier LA. Bone marrow concentrate and platelet-rich plasma differ in cell distribution and interleukin 1 receptor antagonist protein concentration [published online February 1, 2016]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. doi:10.1007/s00167-016-3981-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Wehling P., Moser C., Frisbie D. Autologous conditioned serum in the treatment of orthopedic diseases: The orthokine therapy. Biodrugs. 2007;21:323–332. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200721050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chahla J., Dean C.S., Moatshe G., Pascual-Garrido C., Serra Cruz R., LaPrade R.F. Concentrated bone marrow aspirate for the treatment of chondral injuries and osteoarthritis of the knee: A systematic review of outcomes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4 doi: 10.1177/2325967115625481. 2325967115625481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arbeloa-Gutierrez L., Dean C.S., Chahla J., Pascual-Garrido C. Core decompression augmented with autologous bone marrow aspiration concentrate for early avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5:e615–e620. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enea D., Cecconi S., Calcagno S., Busilacchi A., Manzotti S., Gigante A. One-step cartilage repair in the knee: Collagen-covered microfracture and autologous bone marrow concentrate. A pilot study. Knee. 2015;22:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gobbi A., Chaurasia S., Karnatzikos G., Nakamura N. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation versus multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large patellofemoral chondral lesions: A nonrandomized prospective trial. Cartilage. 2015;6:82–97. doi: 10.1177/1947603514563597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gobbi A., Karnatzikos G., Sankineani S.R. One-step surgery with multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large full-thickness chondral defects of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:648–657. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gobbi A., Karnatzikos G., Scotti C., Mahajan V., Mazzucco L., Grigolo B. One-step cartilage repair with bone marrow aspirate concentrated cells and collagen matrix in full-thickness knee cartilage lesions: Results at 2-year follow-up. Cartilage. 2011;2:286–299. doi: 10.1177/1947603510392023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skowronski J., Rutka M. Osteochondral lesions of the knee reconstructed with mesenchymal stem cells—Results. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2013;15:195–204. doi: 10.5604/15093492.1058409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skowronski J., Skowronski R., Rutka M. Large cartilage lesions of the knee treated with bone marrow concentrate and collagen membrane—Results. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2013;15:69–76. doi: 10.5604/15093492.1012405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J.D., Lee G.W., Jung G.H. Clinical outcome of autologous bone marrow aspirates concentrate (BMAC) injection in degenerative arthritis of the knee. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24:1505–1511. doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fortier L.A., Potter H.G., Rickey E.J. Concentrated bone marrow aspirate improves full-thickness cartilage repair compared with microfracture in the equine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1927–1937. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lavasani M., Robinson A.R., Lu A. Muscle-derived stem/progenitor cell dysfunction limits healthspan and lifespan in a murine progeria model. Nat Commun. 2012;3:608. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centeno C., Pitts J., Al-Sayegh H., Freeman M. Efficacy of autologous bone marrow concentrate for knee osteoarthritis with and without adipose graft. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:370621. doi: 10.1155/2014/370621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hauser R.A., Orlofsky A. Regenerative injection therapy with whole bone marrow aspirate for degenerative joint disease: A case series. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;6:65–72. doi: 10.4137/CMAMD.S10951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enea D., Cecconi S., Calcagno S. Single-stage cartilage repair in the knee with microfracture covered with a resorbable polymer-based matrix and autologous bone marrow concentrate. Knee. 2013;20:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasemkijwattana C., Hongeng S., Kesprayura S., Rungsinaporn V., Chaipinyo K., Chansiri K. Autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells implantation for cartilage defects: Two cases report. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:395–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marmotti A., Rossi R., Castoldi F., Roveda E., Michielon G., Peretti G.M. PRP and articular cartilage: A clinical update. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:542502. doi: 10.1155/2015/542502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Breitbach M., Bostani T., Roell W. Potential risks of bone marrow cell transplantation into infarcted hearts. Blood. 2007;110:1362–1369. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The patient is positioned in the prone position. The left posterior iliac crest is identified and sterilely prepped and draped. Six milliliters of 1% lidocaine local anesthetic is injected into the skin and down to the periosteum over the desired BMAC harvest site. The bony landmarks are palpated again and a bone marrow aspiration trochar and needle assembly are percutaneously inserted through the skin and subcutaneous tissue until it reaches the posterior iliac crest. The trochar is then used to probe along the crest from anterior to posterior and then centered between the outer and inner walls of the iliac crest. Then a power instrument is used to advance the trochar through the dense cortical bone into the medullary cavity of the posterior iliac crest. Needle trajectory should be perpendicular to the PSIS. Prior to aspiration, 1 mL of ACD-A is preloaded into the syringe and injected into the trochar. Approximately 50-60 mL of bone marrow is aspirated, which requires the use of 30- or 10-mL syringes. Use of the 30-mL syringes offers more control during harvest and is the senior author's preferred method. The BMAC aspiration sample is then processed after it is harvested. The bone marrow is placed in a centrifuge. The sample is then spun at a rate of 3,200 rpm for 15 minutes. Typically, a 6-mL sample of BMAC is yielded after processing. The BMAC is subsequently injected either intra-articularly or into an extra-articular surgical site after the procedure is ended to ensure the BMAC is placed at its desired location. (ACD-A, anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution, formula A; BMAC, bone marrow aspirate concentrate.)