Abstract

Dermoid cysts are rare masses of the oral cavity derived from ectodermal elements. These are benign, slow-growing tumors that are typically asymptomatic but cause complications of inflammation or dysphagia, dystonia, and airway encroachment due to mass effects. We report the case of a 17 year old female with a painless mass in the left side of the oral cavity. Ultrasound findings demonstrated non-specific findings of a cystic lesion, and definite diagnosis was made with contrast-enhanced CT and intraoperatively with pathologic confirmation. This retrospective report highlights the challenges in evaluating masses of the oral cavity with imaging and provides a comprehensive discussion on imaging of oral masses on various imaging modalities to guide diagnosis and management.

Keywords: Dermoid Cyst, Pediatrics, Oral Cavity, Ultrasound, Computed Tomography, Histopathology

CASE REPORT

A 17 year old Hispanic female with no significant past medical history presented to the outpatient clinic with painless left neck mass that she noticed for several days before presentation. She was afebrile without odynophagia, overlying erythema, or sore throat. Physical exam revealed a non-tender, mobile mass with no nodularity. Regional lymphadenopathy was absent, trachea was midline, and no thyroid masses were palpable. Examination of the oropharynx was unremarkable. Initial laboratory studies were within normal limits. Epstein-Barr virus antibody testing, Quantiferon Gold, and Bartonella antibody titers were all negative for recent infection.

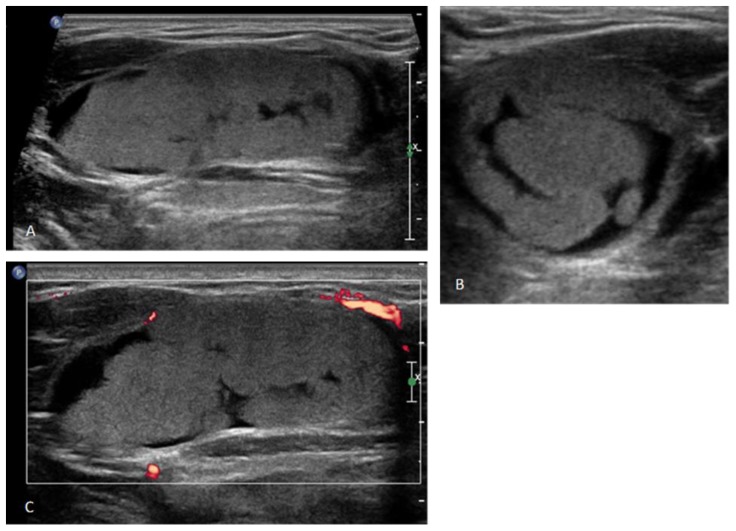

Ultrasound (US) demonstrated a well-circumscribed, avascular mass in the left side of the oral cavity measuring 4.7 × 1.9 × 2.8 cm. The mass had internal lobular echogenic areas and curvilinear anechoic areas. No internal flow was appreciated on Doppler imaging. Furthermore, no surrounding inflammatory changes were noted (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

17 year old female with a dermoid cyst in the left side of oral cavity.

Findings: Gray Scale Ultrasound images in long axis (A) and short axis (B) demonstrate a well-defined, lobulated echogenic mass along with hypoechoic areas interspersed in between. Long axis color Doppler image (C) demonstrates absence of vascularity within the mass.

Technique: Gray Scale Ultrasound images in long axis (A) and short axis (B) and long axis color Doppler image (C).

At this time, the differential diagnosis included a ranula, a necrotic neoplastic process, evolving hematoma, lymphatic malformation, a suppurative node, or abscess. Due to the nonspecific appearance of the mass on US, a contrast-enhanced CT was obtained. CT demonstrated an ovoid lesion at the floor of the oral cavity on the left side within the sublingual space. There was no osseous erosion or destruction of the adjacent mandible. The margins of the lesion were well-defined with no extension into the submandibular space. The lesion demonstrated areas of hypodensity exhibiting fat attenuation (Hounsfield units −30 to −20) within it, suggesting a dermoid cyst (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

17 year old female with a dermoid cyst in the left side of oral cavity.

Findings: Note an ovoid lesion at the floor of the oral cavity on the left side within the sublingual space. Lesion measures 4.0 × 3.0 × 1.5 cm. There are areas of negative Hounsfield units (−30 to −20 HU) within the mass suggesting a fat component. No osseous erosion or destruction of the adjacent mandible is noted. No extension into the submandibular space is seen. There is mild expansion of the inferior aspect of the lesion, which displaces the mylohyoid muscle inferiorly. There is no enhancement with contrast.

Technique: Coronal, Axial and Sagittal CT, 150mAs, 120kV, 3 mm slice thickness, 80 ml Iohexol contrast injected iv

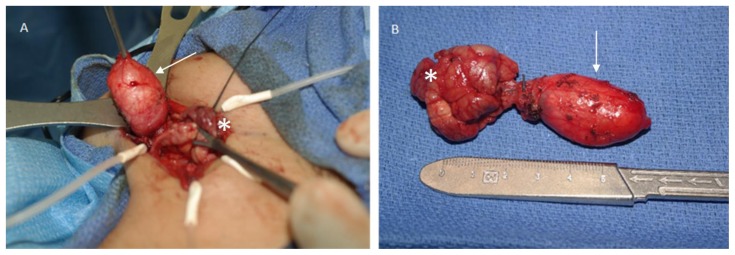

For definitive diagnosis and management, the patient and her family were offered surgical excision of the mass, including the submandibular gland. Extirpation of the mass was accomplished using a curvilinear cervical incision in the neck approximately 2 cm below the angle of the mandible. Dissection through the superficial and investing fascial layers of the neck allowed identification of the submandibular gland and mylohyoid muscle. The submandibular gland was freed from the mylohyoid using blunt dissection. Slightly anterior and lateral to the mylohyoid, the posterior edge of the cystic mass was identified. This was bluntly dissected free and delivered en bloc. It remained somewhat attached through a fibrous band to the submandibular gland itself (Figure 3). The submandibular gland was removed in standard fashion taking care to identify and avoid injury to the hypoglossal and lingual nerves. A large, nearly 2 cm lymph node in the left submandibular triangle was also identified and carefully dissected free bluntly. A Jackson-Pratt (J-P) drain was placed and the wound closed primarily. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course with minimal drain output. The drain was removed, and the patient was discharged the next day. She continues to do well without signs of recurrence or infection.

Figure 3.

17 year old female with dermoid cyst in the left oral cavity.

Findings: Pictures demonstrate the surgical excision of the mass on the left and gross surgical specimen on the right side. Dermoid (arrow) is seen adherent to the submandibular gland (asterisk).

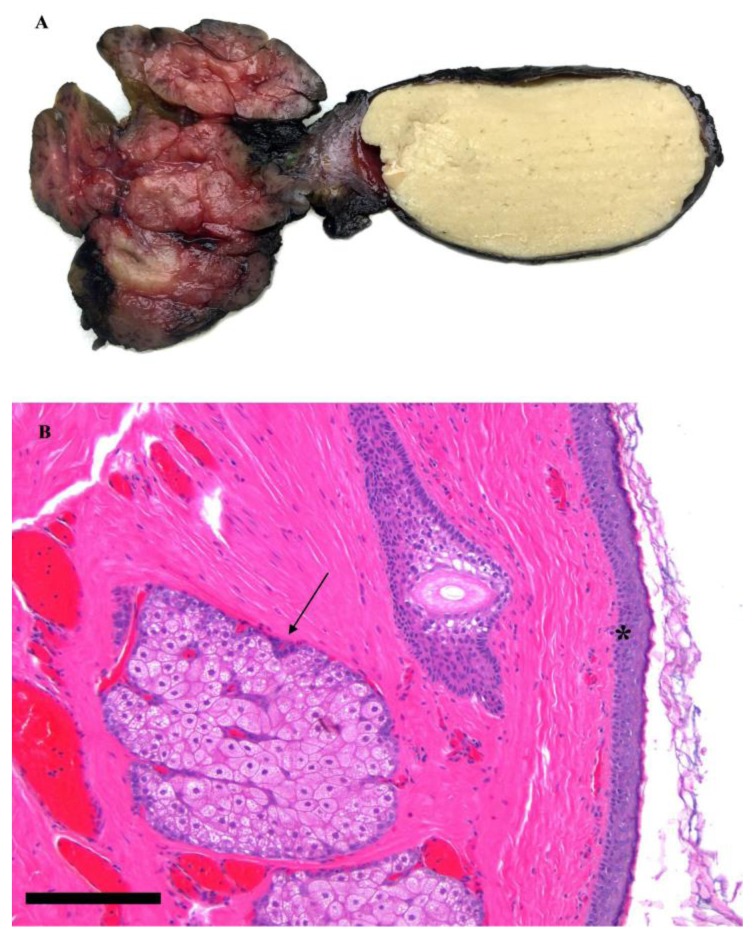

Gross pathological evaluation revealed a 3.5 × 1.7 × 1.0 cm thin-walled, unilocular cystic mass filled with keratin debris (Figure 4A). Microscopically, the cyst lining (Figure 4B) was composed of squamous epithelium with keratin debris (asterisk) and sebaceous glands with associated hair follicles (arrow). There was no evidence of malignancy. The cyst was adherent to the salivary gland but did not appear to arise from the salivary gland parenchyma. In the space between the cyst and the gland, there was evidence of chronic inflammation and giant cell reaction, suggesting a history of microscopic rupture and repair. The lymph node was found to be reactive in nature without signs of malignancy. These histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of a dermoid cyst.

Figure 4.

17 year old female with a dermoid cyst in the left oral cavity.

Findings: Gross pathological specimen demonstrating a thin-walled, unilocular cystic mass filled with keratin debris (Figure 4A). Microscopically, the cyst lining is composed of squamous epithelium with keratin debris (asterisk) and sebaceous glands with associated hair follicles (arrow) (Figure 4B). There was no evidence of malignancy. The cyst was adherent to the salivary gland but did not appear to arise from the salivary gland parenchyma. In the space between the cyst and the gland, there was evidence of chronic inflammation and giant cell reaction, suggesting a history of microscopic rupture and repair.

DISCUSSION

Etiology & Demographics

Dermoid cysts are benign lesions arising from totipotent stem cells that undergo ectodermal differentiation [1]. The cyst lining is composed of keratinizing squamous epithelium and typically contains skin appendages such as sebaceous glands and hair follicles. This is differentiated from epidermoid cysts, which do not contain these adnexal structures, and teratoid cysts, which contain tissue derived from mesodermal and endodermal germinal layers in addition to ectodermal elements. Grossly, these cysts are thin-walled (2–6 mm thick) and often contain an oily, pale yellow keratinous material [2]. In this case, the histopathology was consistent with a dermoid cyst, as only epidermal-type squamous epithelium and skin adnexa was found.

Nearly 34% of dermoid cysts are found in the head and neck, of which 6.5% are located at the floor of the mouth, making these uncommon entities [3]. Unlike in our patient, they typically occur in the midline and anterior portions of the oral cavity and tend to manifest in the second or third decade of life [4,5]. Dermoids are thought to arise congenitally from entrapment of ectodermal tissue during midline closure of the first and second branchial arches [6,7]. They may also stem from surgical or accidental implantation of epithelium into the jaw mesenchyme leading to proliferation of epithelial cells in the deeper tissues [8]. In our case, there was no traumatic history noted.

Clinical & Imaging Findings

Complications of dermoids include dysphagia, dysphonia, and dyspnea with airway encroachment when large enough [9]. In this case, there was no extension into the midline nor was there displacement of the tongue, leaving our patient largely asymptomatic. Uncommonly, cysts may rupture and present an acute inflammatory response. Malignant transformation is rare, reported as less than 5% [10].

Ultrasound imaging is the initial diagnostic modality of choice for oral lesions. Dermoids appear as well-circumscribed, unilocular cysts that may contain either anechoic or hypoechoic regions or multiple echogenic nodules because of the presence of epithelial debris or skin appendages [2,11]. In our case, the appearance on ultrasound was very non-specific and it was difficult to suggest a diagnosis of dermoid based on the ultrasound findings alone.

CT scan demonstrates a thin-walled, unilocular mass filled with homogenous, hypo-attenuating material containing multiple hypo-attenuating fat nodules. This gives a “sack of marbles” appearance that is pathognomonic for dermoid cysts [12]. Similarly in our patient, CT demonstrated areas of hypodensity with interspersed regions of fat attenuation, suggesting the diagnosis of a dermoid, whereas US failed to be specific.

MRI characteristics are variable. On T2-weighted imaging, dermoids tend to exhibit a hyperintense signal. T1-weighted imaging demonstrates a variable signal depending on fat content [13].

Treatment & Prognosis

CT or MRI imaging best delineates the internal architecture of dermoid cysts and facilitates exact visualization of the location of the lesion in relation to the surrounding anatomy to guide surgical management. The mylohyoid muscle separates the sublingual from submental and submandibular spaces and is a key landmark used to determine whether an intraoral or cervical approach is most appropriate during surgery [14]. Lesions above the mylohyoid are typically operated on intraorally, whereas those below the muscle are removed using an extraoral approach. However, for large sublingual cysts, an extraoral approach may be preferred [15,16]. Prognosis following surgical removal is excellent, and postoperative complications are minimal [17].

Differential Diagnosis

Ranula

A ranula is a mucous cyst confined to the floor of the mouth and caused by obstruction of the sublingual gland. They appear as thin-walled, cystic lesions on US and are hypodense on CT, mimicking dermoid cysts; however, these lesions do not exhibit areas of fat attenuation on CT, which is a feature that can help in differentiating these lesions from dermoids. Further, complicated ranulas that have ruptured would demonstrate a thin “tail” of fluid from the collapsed sublingual space that appears to dive into the submandibular space on imaging. On MRI, a ranula appears as a high-intensity on T2-weighted images and may be abnormally high on T1-weighted images because of its high protein content [4]. Histologic appearance is similar to that of mucoceles, where spillage of mucin causes formation of a granulation tissue that contains foamy histiocytes [2,18].

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Branchial cleft cysts account for 20% of pediatric neck masses [19]. They arise during embryogenesis due to failure of the branchial cleft to obliterate or fuse leading to cyst or fistula formation. They generally occur unilaterally, and anatomic location of the cyst is dependent on cleft origin. First branchial cleft cysts are rare (< 1%) and typically appear on the face near the auricle. Second branchial cleft cysts account for the majority and are found along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Third and fourth branchial cleft cysts are uncommon but also located anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; however, they typically are found lower in the neck compared to second branchial cleft cysts [4]. These cysts appear as sharply demarcated, hypoechoic masses with thin walls and posterior enhancement on US. On CT, they are seen as well-circumscribed, non-enhancing masses of homogenous low attenuation. In second branchial cleft cysts, a beak sign may be seen, which is an extension of the cyst wall curving medially behind the internal and external carotid arteries. On MRI, these cysts typically display hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging whereas on T1-weighted imaging, the cyst fluid varies from hypointense to hyperintense depending on protein content [20]. Histologically, the cyst lining is composed of either squamous or columnar cells with lymphoid infiltrate, often with prominent germinal centers. Cholesterol crystals may be found in the internal fluid [21].

Thyroglossal Duct Cyst

During embryogenesis, the thyroid descends from the tongue at the level of the foramen cecum to the lower portion of the anterior neck, forming the thyroglossal duct during this migration period. Once the thyroid reaches its final position at the base of the neck, the duct disappears. However in some cases, portions of the tract persist causing sinus, fistula or cyst formation. Thyroglossal duct cysts are midline structures, typically at the posterior tongue root, and are unilocular with anechoic fluid and no internal vascularity on US. On CT, they appear homogeneous with no complex elements, such as fat. An uncomplicated thyroglossal duct cyst will typically have high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging and low signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging; however, they may appear hyperintense on T1-weighted images due to hemorrhage, infection, or high protein content in the cyst fluid [4]. Histologic examination demonstrates a cyst lining composed of pseudociliated columnar and cuboidal epithelium as well as ectopic thyroid tissue with thyroid follicles [22].

Lymphatic Malformation

Lymphatic malformations, or lymphangiomas, are the result of maldevelopment of lymphatic vessels and failure of these vessels to communicate with normal lymph drainage tracts. They are typically benign, slow-growing lesions that become dilated due to fluid accumulation and cyst formation. Lymphangiomas that involve the floor of the mouth and the neck are called cystic hygromas. On US, these appear as thin-walled unilocular or multilocular lesions with anechoic areas, and they do not demonstrate vascularity on Doppler examination. Similar to thyroglossal duct cysts, a lymphatic malformation of the oral cavity would also appear homogenous on CT, but may be multilocular and contain proteinaceous material, fluid, blood, or fat within the lesion. On MRI, lymphangiomas typically appear hyperintense on T2-weighted images whereas on T1-weighted images, the signal intensity is variable depending on the protein content [18]. These lesions are further characterized as macrocystic (large, interconnected cysts > 2 cm in volume and lined by a thin endothelium), microcystic (< 2 cm in volume), or mixed type based on histopathologic findings. In each, the vessel walls typically contain lymphoid aggregates and the spaces consist of proteinaceous fluid and lymphocytes [2,23].

Abscess

Oral abscesses typically are the result of odontogenic infections due to poor oral hygiene or recent dental manipulation. Oral abscesses have a defined fibrous capsule that is thick and irregular compared to thin-walled cysts. On US, these lesions have a central anechoic or hypoechoic component with a thick, irregular peripheral wall that demonstrates hyperemia on Doppler examination. On CT, these lesions demonstrate a central hypoattenuating component with peripheral enhancement in addition to soft tissue edema. MRI typically demonstrate hyperintensity on T2-weighted images and hypointensity on T1-weighted images. In addition, a characteristic feature on MRI is restricted diffusion of the central abscess cavity [2]. Histology would show extensive fibrosis of the wall, neutrophil aggregation surrounding a liquid center with keratinous debris, and giant cell formation [4].

Hemangioma

Hemangiomas are formed from pathologic endothelial cell proliferation leading to malformation of vascular vessels. These are true neoplasms that undergo a two-stage process of growth (proliferation) and regression (involution). Congenital hemangiomas are fully developed at birth and subsequently do not grow whereas infantile hemangiomas are small or absent at birth and grow rapidly over the first several months of life followed by involution over months to years. On US, these lesions appear as echogenic, focal masses that demonstrate arterial as well as venous flow on spectral Doppler evaluation. On CT, these lesions appear as lobulated, enhancing masses with arterial feeders as well as prominent draining veins. On MRI, hemangiomas typically appear hyperintense on T2-weighted images and of intermediate intensity on T1-weighted imaging [18]. Histology is classic for numerous closely aggregated vascular channels with endothelial cells embedded. Deposition of hemosiderin pigment due to vessel rupture may be observed.

Neoplasm

Both benign and malignant tumors must be considered in the differential of pediatric neck masses, as malignancy represents 11–15% of all neck masses in children [4]. Lymphoma is the third most common pediatric cancer and the most common malignancy in the neck. Lipomas, although more common in adults, may also be considered in the pediatric patient, as they are the most common benign mesenchymal tumors [18]. Further, a benign tumor of the salivary gland, such as of the submandibular gland, must be included in the differential. For instance, a pleomorphic adenoma is typically seen as a hypoechoic mass on US and lobulated homogenous mass on CT with foci of necrosis if larger. Small regions of calcification are common. MRI would demonstrate hyperintensity with a rim of hypointensity representing a fibrous capsule on T2-weighted imaging and would be hypointense on T1-weighted images. Histology would demonstrate both epithelial and myoepithelial tissue with myxoid or cartilaginous stroma. Lastly, mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common malignant salivary gland tumor of childhood. US typically shows a focal hypoechoic lesion with heterogeneous echotexture. Though there are no specific imaging features on CT, most low grade tumors have well defined margins, while high grade tumors are ill defined and may demonstrate local infiltration. On MRI, these tumors would have intermediate to high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, with cystic regions appearing hyperintense. On T1-weighted images, they exhibit low to intermediate signal, with cystic areas appearing hypointense. Histopathology would demonstrate a mixture of mucin-producing columnar cells and epidermoid (squamous) cells as well as prominent cellular atypia and pleomorphism if high-grade [24].

TEACHING POINT

Dermoid cysts are rare masses of the oral cavity, and diagnosis on ultrasound can be very challenging. CT can add vital clues to a specific diagnosis, and knowledge of imaging appearances of various masses of the oral cavity is important to clinch the diagnosis and guide surgical management. This case illustrates that dermoids should be included in the imaging differentials for a neck mass in a child that demonstrates “sack of marble” appearance and hypodensity (negative Hounsfield units) on CT.

Table 1.

Radiologic differential diagnosis of masses of the oral cavity with histopathologic correlation.

| Diagnosis | Ultrasound | CT | MRI | Histopathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dermoid Cyst | Unilocular cyst; may contain anechoic or hypoechoic regions or multiple echogenic nodules due to epithelial debris or skin appendages | Thin-walled, unilocular mass filled with homogenous, hypo-attenuating material containing multiple hypo-attenuating fat nodules (“sack of marbles”) | T2 – hyperintense signal, may be heterogenous T1 – variable signal depending on fat content, usually bright |

Cyst lining contains keratinizing squamous epithelium and components of ectodermal elements (i.e. sebaceous glands, hair follicles) |

| Ranula | Thin-walled, cystic (anechoic) lesion; may contain internal echoes due to debris; no internal flow | Hypodense; complicated (ruptured) ranulas: thin “tail” of fluid from collapsed sublingual space that dives into submandibular space | T2 – high signal T1 – typically low signal (may be high due too high protein content) |

Predominant histiocytes which stain positive for mucin; granulation tissue formation |

| Branchial Cleft Cyst | Well-circumscribed, hypoechoic; thin walls and posterior enhancement | Homogenous low attenuation; second branchial cleft cysts exhibit “beak sign”: medial extension of cyst wall behind ICA and ECA | T2 – usually high signal T1 – variable signal dependent on protein content (high signal if high protein content; low signal if low protein content) |

Squamous or columnar lining with lymphoid infiltrate and prominent germinal centers; cholesterol crystals in internal fluid |

| Thyroglossal Duct Cyst | Unilocular with anechoic fluid and no internal vascularity | Homogeneous with no complex elements (e.g. fat) | T2 – high signal intensity T1 – low signal intensity if low protein; high signal due to previous hemorrhage, infection, or high protein |

Pseudostratified columnar and cuboidal epithelial lining with ectopic thyroid gland tissue |

| Lymphatic Malformation | Unilocular or multilocular with thin septations and anechoic areas; no vascularity on Doppler | Homogenous; may be multilocular and contain proteinaceous material, fluid, blood, or fat within | T2 – usually high signal intensity T1 – variable; dependent on protein content |

Interconnected cysts with thin endothelial lining containing lymphoid aggregates; fluid contains proteinaceous material and lymphocytes |

| Abscess | Thick, irregular fibrous capsule with anechoic fluid | Capsular ring enhancement; thick, irregular walls | Restricted diffusion of the central abscess cavity. T2 – high signal intensity T1 – low signal intensity |

Inflammatory cell aggregation and giant cell formation; liquid center with keratinous debris; fibrosis of wall |

| Hemangioma | Echogenic on ultrasound; high-flow vascularity on color Doppler | Lobulated, enhancing mass with arterial feeders and draining veins | T2 – multiple, high signal intensity lobules T1 – intermediate signal intensity, between that of muscle and fat |

Aggregation of vascular channels; endothelial cells in wall; hemosiderin deposition |

| Salivary Gland Tumor | Hypoechoic, well-circumscribed mass; heterogeneous echotexture |

Pleomorphic Adenoma - lobulated, homogenous mass with foci of necrosis Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma – solid mass with possible infiltration, may have cystic areas and calcification. |

Pleomorphic Adenoma –T2: high intensity with rim of decreased signal intensity representing surrounding fibrous capsule; T1: low intensity Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma – T2: intermediate to high signal, cystic areas hyperintense; T1: low to intermediate signal, cystic spaces hypointense |

Pleomorphic Adenoma - epithelial and myoepithelial tissue with stromal components ranging from myxoid to cartilage Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma – mucin-producing cells plus epidermoid (squamous) cells; cellular atypia and pleomorphism if high-grade |

Table 2.

Summary table of oral dermoid cysts.

| Etiology | Entrapment of ectodermal tissue during midline closure of the first and second branchial arches |

| Prevalence | Rare (~ 2% of head and neck dermoid cysts) |

| Gender Ratio | Equal |

| Age Predilection | Second and third decades |

| Risk Factors | Congenital or sporadic (with accidental trauma or surgical implantation) |

| Presentation | Painless mass; potential for dysphagia, dysphonia, and dyspnea due to size; may rupture and cause inflammatory response |

| Treatment | Surgical excision |

| Prognosis | Benign, slow-growing; malignant transformation in < 5% |

| Pathologic Features | Cyst lining is composed of keratinizing squamous epithelium and contains skin appendages such as sebaceous glands and hair follicles. Grossly, are thin-walled (2–6 mm thick) and contain an oily, pale yellow keratinous material. |

| Imaging Findings |

US: well-circumscribed, unilocular cysts that may contain anechoic or hypoechoic regions or multiple echogenic nodules due to presence of epithelial debris or skin appendages. CT: thin-walled, unilocular mass filled with homogenous, hypo-attenuating material containing multiple hypo-attenuating fat nodules; “sack of marbles” appearance. MRI (T2-weighted): hyperintense signal on T2, may be heterogeneous MRI (T1-weighted): variable signal depending on fat content, usually bright on T1 |

ABBREVIATIONS

- CT

Computed Tomography

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- US

Ultrasound

REFERENCES

- 1.Hills SE, Maddalozzo J. Congenital lesions of epithelial origin. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2015;48(1):209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischbein NJ, Ong KC. Chapter 3 Radiology. In: Lalwani AK, editor. CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment in Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery. 3e. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor BW, Erich JB, Dockerty MB. Dermoids of the head and neck. Minnesota medicine. 1966;49(10):1535–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goins MR, Beasley MS. Pediatric neck masses. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2012;24(3):457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vieira EM, Borges AH, Volpato LE, et al. Unusual dermoid cyst in oral cavity. Case reports in pathology. 2014;2014:389752. doi: 10.1155/2014/389752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paradis J, Koltai PJ. Pediatric teratoma and dermoid cysts. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2015;48(1):121–136. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon PE, Faquin WC, Lahey E, Kaban LB. Floor-of-mouth dermoid cysts: report of 3 variants and a suggested change in terminology. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2013;71(6):1034–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirza S, Fadl S, Napaki S, Abualruz A. Case report of complicated epidermoid cyst of the floor of the mouth: Radiology-histopathology correlation. Qatar medical journal. 2014;2014(1):12–16. doi: 10.5339/qmj.2014.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diercks GR, Iannuzzi RA, McCowen K, Sadow PM. Dermoid cyst of the lateral neck associated with the thyroid gland: a case report and review of the literature. Endocrine pathology. 2013;24(1):45–48. doi: 10.1007/s12022-013-9234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyriakidou E, Howe T, Veale B, Atkins S. Sublingual dermoid cysts: case report and review of the literature. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2015;129(10):1036–1039. doi: 10.1017/S0022215115001887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards RM, Chapman T, Horn DL, Paladin AM, Iyer RS. Imaging of pediatric floor of mouth lesions. Pediatric radiology. 2013;43(5):523–535. doi: 10.1007/s00247-013-2620-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter TB, Paplanus SH, Chernin MM, Coulthard SW. Dermoid cyst of the floor of the mouth: CT appearance. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1983;141(6):1239–1240. doi: 10.2214/ajr.141.6.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikeda K, Koseki T, Maehara M, et al. Hourglass-shaped sublingual dermoid cyst: MRI features. Radiation medicine. 2007;25(6):306–308. doi: 10.1007/s11604-007-0139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dillon JR, Avillo AJ, Nelson BL. Dermoid Cyst of the Floor of the Mouth. Head and neck pathology. 2015;9(3):376–378. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0576-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim IK, Kwak HJ, Choi J, Han JY, Park SW. Coexisting sublingual and submental dermoid cysts in an infant. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2006;102(6):778–781. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gol IH, Kiyici H, Yildirim E, Arda IS, Hicsonmez A. Congenital sublingual teratoid cyst: a case report and literature review. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2005;40(5):e9–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pryor SG, Lewis JE, Weaver AL, Orvidas LJ. Pediatric dermoid cysts of the head and neck. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2005;132(6):938–942. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meesa IR, Srinivasan A. Imaging of the oral cavity. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2015;53(1):99–114. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pincus RL. Congenital neck masses and cysts. In: Bailey BJ, editor. Head & Neck Surgery - Otolaryngology. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. p. 933. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mittal MK, Malik A, Sureka B, Thukral BB. Cystic masses of neck: A pictorial review. The Indian Journal of Radiology & Imaging. 2012;22(4):334–343. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.111488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, Ingale Y. Branchial cleft cyst: A case report and review of literature. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology : JOMFP. 2014;18(1):150–150. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.131950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yim MT, Tran HD, Chandy BM. Incidental radiographic findings of thyroglossal duct cysts: Prevalence and management. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016;89:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stern JS, Ginat DT, Nicholas JL, Ryan ME. Imaging of pediatric head and neck masses. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2015;48(1):225–246. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Triantafillidou K, Dimitrakopoulos J, Iordanidis F, Koufogiannis D. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of minor salivary glands: a clinical study of 16 cases and review of the literature. Oral diseases. 2006;12(4):364–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]